Craig Pirrong's Blog, page 19

July 14, 2023

The Hydrogen Economy, or The Hindenberg Economy? Or, Gosplan Goes Gassy

The Biden administration, courtesy of the delusionally titled Inflation Reduction Act, has made a huge spending commitment on alternative fuels, and in particular “clean” hydrogen, i.e., hydrogen not produced from fossil fuels (such as methane). Most of the “green” hydrogen stimulus involves supply-side subsidies (especially a $3/kg production tax credit, but also loans to be doled out by the administrative state). The Infrastructure Law sets aside funds for hydrogen electrolysis and hydrogen “hubs” (like that just announced for Germany). The administration is also attempting to make “the economic case for demand-side support,” such power purchase agreements (PPAs), contracts-for-differences (CFDs), advanced market commitments (made by whom?), and prizes (funded by whom?).

It’s hard to know where to begin in criticizing this mess. The biggest problem is that it attempts to address the climate issue (which I will take as a given, focusing on means not ends) by picking technologies. This almost never ends well. First, there is the knowledge problem–bureaucratic governments do not possess the information to make these technology choices. Second, there is the rent seeking/corruption problem–which exacerbates the knowledge problem, as interested parties exploit the ignorance of bureaucrats and funders, and their political connections, to induce investments based not on their economic virtues but instead on political influence.

There are also serious doubts about whether hydrogen qua hydrogen is the right alternative fuel given that it poses numerous problems and costs. The first is that using renewable energy to produce green hydrogen is extremely expensive. The second is that, well, hydrogen is highly explosive: I distinctly remember my 8th grade science teacher, Mr. Fisch, using electrolysis to fill a test tube with hydrogen, putting in a piece of chalk, then lighting a match to set off an explosion that sent the chalk flying across the room. You didn’t have Mr. Fisch as a teacher, but perhaps you’ve heard of the Hindenberg:

Explosiveness creates hazards, of course, and mitigation of them is expensive. Hydrogen is also extremely expensive to transport and store and requires a new and distinct transportation and storage system.

We are talking trillions of dollars to create “the hydrogen economy”–something even its boosters admit. Hell, they brag about it.

Hydrogen “carried” with carbon, in the form of ammonia or methanol, pose fewer problems (although ammonia in particular is nasty stuff). They are also costly, and it is clearly uncertain whether “green” forms of these hydrogen carriers are economical ways to reduce carbon emissions from fuels for transportation and power generation.

But the administration (and Europe too) have gone all in on hydrogen. Why? Maybe because their extreme antipathy towards carbon leads them to disdain fuels with any carbon in them.

Having chosen its technology, for better or more likely worse, now the administration is focused on how to force its adoption. The supply-side incentives are clear enough, so now there is a pivot to the demand-side, as expressed in the appallingly shoddy Council of Economic Advisors document linked above.

According to the CEA–and not just the CEA, as will be seen shortly–the problem is that “[r]eal or perceived risks around clean energy projects can raise the cost of accessing capital, which could slow the rate at which projects like those in the hydrogen hubs program achieve commercialization..”

Well, I should hope so! That is, I should hope that risks are taken into account when allocating capital!

John Kerry flogged the risk issue on MSNBC (h/t Powerline):

“What’s preventing it is, to some degree, fear, uncertainty about the marketplace. People who manage very significant amounts of money have a fiduciary responsibility, an obligation to the people they manage it for not to lose the money, but to produce returns on that investment. Pension funds, many of them, are very careful about those investments in order to make certain they have the money to pay out to the pensioners who work for that money all their lives. So, there are tricky components of making sure that you have taken the risk away from these investments. And energy, which is what the climate crisis is all about, it’s about energy, it’s about how we fuel our homes, how we heat our homes, how we light our factories, how we drive and go from place to place.”

Damn those money managers for taking into account the risks and rewards of the money their investors entrust to them! Don’t they understand that John Effing Kerry knows what is right for humanity????? After all, he flies around the world in a private jet sharing his wisdom (and then dissembles about it before Congress).

I loved this part: “So, there are tricky components of making sure that you have taken the risk away from these investments.” Does John Kerry have a magic box into which he can make the risks disappear? Do tell!

Of course he doesn’t. What he means, clearly, is that the government must somehow absorb the risks inherent in the technology that they have already decided upon–apparently without analyzing those risks fully or carefully, or wondering whether maybe these damned investors might know something they don’t. (Of course they don’t wonder that! They are all knowing, right?)

At least the CEA attempts to put lipstick on the pig and raise some economic arguments to justify the need for demand-side support. There are market failures! Government never fails, but markets do, right?

In my experience the concept of market failure is most likely to be advanced when the market fails to do what someone thinks should be done, or wants to be done, based on their own vision. That is, when the market disagrees with someone, the market has failed! Especially when that someone is a member of what Thomas Sowell calls “The Anointed.”

The CEA basically cites to some theoretical possibilities. At the core of their argument is that learning by doing, including learning-by-doing that “spills over” among companies, can lead to inefficient investment. The CEA advances a couple of reasons.

One is a contracting failure. LBD–moving down the learning curve–reduces costs, meaning that prices are expected to fall. So, according the CEA, potential buyers are unwilling to enter into long term contracts for fear of agreeing to pay a price that will turn out to be too high: “if rapid declines in technology costs are expected, the willingness of private sector end-users to seek out such contracts with clean energy developers will be limited” (emphasis added). Without such contracts, hydrogen project developers can’t secure financing, so plants won’t get built, no learning takes place, and costs don’t fall. The Curly Equilibrium, in other words:

Really? If costs are expected to fall, market participants can enter contracts with de-escalator clauses, i.e., contractual prices that fall over time. Apparently the CEA only envisions contracts at a fixed price that extends through the life of the contract. But even then, given anticipated cost declines, the developer would be willing to sell at a price below the initial cost, basically, at the average cost expected over the life of the contract.

The CEA mentions the risks of of the magnitude of cost declines, but again, that should be a material consideration in any contracting and investment decision. Is the CEA arguing that the risk compensation demanded by borrowers will be excessive? They don’t say so explicitly, but that’s what you would need to argue that the prices in these contracts would be “too low” and thereby stymie investment.

I’d also note that indexed prices, widely used in a variety of commodity off-take agreements, eliminate the risk to buyers of locking in too high a price. They also address the asymmetric information problem that the CEA frets about. If the developer has better information about the likely trajectory of price declines, then yes, buyers looking at fixed price deals or deals with mechanical (non-market based) price de-escalators face a “winners’ curse” problem: the developer will agree to terms that overestimate his (better) forecast of future prices, and reject deals that underestimate.

I think in fact that the issue is that there is considerable uncertainty among all parties, developers and buyers alike, regarding what the future cost trajectory will look like. That is, there is a real risk here, and that risk should be taken into consideration when deciding whether hydrogen investments make sense. And market participants are far better at assessing the risks, and the pricing of those risks, than the government, which is clearly taking a “Damn the risks, full speed ahead!” Approach.

Sorry, but John Kerry et al don’t inspire confidence like Admiral Farragut at Mobile Bay.

One of the proposals under discussion is Contracts for Differences (“CFDs”) in which the government would (perhaps through a non-profit intermediary) provide a guaranteed revenue stream to a developer and absorb the price risk. To work, CFDs require indexing to some market price–and the market price for H2 hasn’t really been created. Further, they require some mechanism to set the guaranteed price, a non-trivial task given the very information asymmetries that the CEA worries about. The government-appointed third party (or the government for that matter) will certainly be the less informed party in any negotiations with developers, and will almost certainly overpay. (Not that they will mind–not their money!) Meaning that the asymmetric information problem the CEA frets about is present in spades in one of their preferred means of addressing it. Further, CFDs have already presented performance issues, with the sellers (those getting the guaranteed revenue stream) treating these contracts like options rather than forwards, and spurning their CFD commitments when market prices rise above the guaranteed price (as has happened with with generators in the UK when power prices spiked).

The CEA also invokes capital market imperfections also driven by asymmetric information that may impede financing if developers know more about the economics of projects than the financiers. This is a hoary old story that has been used to identify alleged market failures since time immemorial. So long ago, in fact, that when Stigler wrote “Imperfections in the Capital Market” (JPE) 56 years ago, he (in typical Stigler fashion) drolly started thus: “The adult economist, once the subject is called to his attention, will recall the frequency and variety of contexts in which he has encountered ‘imperfections-in-the-capital market.'” That is, “capital market imperfections” were an old joke decades ago.

Here’s another one, George! Based on long experience, George was a skeptic. Based on even longer experience, I am too, in this case in particular.

And let’s look at the empirical record. Learning by doing is a ubiquitous phenomenon. Dynamically declining costs in industries with potential information asymmetries abound. Yet industries have developed and thrived nonetheless.

Some examples.

I recently finished a piece describing extensive learning-by-doing in the shale industry, including evidence of learning spillovers and dynamic cost reductions. Yet, the shale sector has not faced problems getting capital or expanding rapidly. Hell, if anything, a common criticism is that shale drillers have obtained too much capital and drilled too much, not that they are starved for capital and drilled too little.

Does the CEA (or John Kerry!) believe the shale sector in the US is too small?

Insofar as spillovers is concerned, the fact that the costs of firm A decline when firm B produces more output is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for an externality. One plausible outcome in oil (as identified in a paper on LBD in conventional drilling by Kellogg in the QJE) is that service firms are the ones that do the learning, and capture and internalize it.

LBD is well-documented for computer chips, which have seen relentless cost and price declines over the years. Yet computer chip factories have been built, and companies especially in the US and Asia have attracted the capital necessary to build these very expensive facilities and build new chip lines nonetheless. (In this industry too, there have been chronic complaints about overcapacity, rather than undercapacity. I am not commenting on the validity of those complaints, just noting that their existence contradicts the notion that dynamic scale economies and price declines due to LBD starve an industry of capital.)

The LNG industry has many of the characteristics that the CEA attributes to hydrogen. Yet this industry has expanded apace for well over 50 years now.

I viewed a presentation by DOE people today in which LNG was raised several times, and as an example not to be followed. DOE advisor Leslie Biddle (ex-Goldman) mentioned LNG several times (“I keep going back to the LNG analogy”), and in a negative way. LNG took 30 years to move to a traded market, dontcha know. And we don’t have that time! We need to create such a market in a year! (DOE’s Undersecretary for Infrastructure David Crane was more generous, giving us all of 5 years.) (Crane was also hyping the idea of hydrogen for everything, including home heating–apparently oblivious to the fact that even Net Zero fanatical Britain has just recently determined that H2 is too dangerous to heat homes.)

In the context of the discussion of a grand government plan to transform the energy system, I couldn’t help but think of Gosplan, or Stalin’s race to industrialization (e.g., the Magnitogorsk Steel Factory). We will inevitably–inevitably–meet the “Dizzy With Success” phase in hydrogen, mark my words.

I note that LNG production grew substantially before it became a traded market, which actually undercuts Biddle’s argument. Even though there was not a liquid traded market for LNG in the first decades of its growth and development, long term contracts, usually using crude (no pun intended) indexing features (like tying prices to Brent), contracts were agreed to, financing was obtained on the backs of these contracts, and liquefaction plants were built.

Oil refining faced many of the conditions that worries the CEA about hydrogen. Kerosene was a radical product early on, with a lot of uncertainty about market adoption. But Rockefeller dramatically expanded output and reduced costs: the cost of kerosene by 2/3rds in 10 years (1870-1880), in large part due to extensive learning and research on all aspects of the value chain. Standard Oil’s supposedly predatory acquisitions of were actually ways by which SO’s knowledge could be combined with physical assets to improve their efficiency.

The co-evolution of gasoline refining and the adoption of the automobile represents another example of investment and falling prices in a new market in a capital intensive industry.

I note that the early refining examples occurred when capital markets were far less developed than is currently the case. I further note that large energy firms (IOCs and NOCs like Aramco in particular) can potentially finance hydrogen (and other alternative energy projects) with cash flows generated by their legacy fossil fuel investments: this would largely eliminate any asymmetric information problem between developer and financier (because the developer is the financier) and developer and customer (because the developer could finance without securing a long term price commitment).

Another example. Electricity generation. Beginning with its inception in the early-1880s, electricity generation was highly technologically dynamic, with substantially declining costs. Yet in a few short years most urban areas in the US were electrified, with numerous private companies competing with government utilities. This was another industry in which overbuilding, rather than under-building, was widely discussed. The movement to price regulation occurred well after the industry developed, and was a reaction to intense price competition: regulation effectively cartelized electricity generation.

One more. Aircraft. LBD was first identified in the production of airframes. This phenomenon was first documented by Wright in 1936, and was subsequently observed in myriad other industries (e.g., Liberty Ship construction in WWII). LBD and the associated cost declines have continued in aircraft construction ever since. And aircraft have been built and aircraft manufacturers have been able to attract the capital to design and build new aircraft that benefit from these cost declines.

In the face of all these examples, the CEA and others making these market failure arguments should identify an industry that died aborning due to the alleged chicken-or-egg problem that makes demand side support of hydrogen investment necessary.

The CEA document has echoes of some rather common, but unpersuasive, arguments for government support of industry, such as the infant industry argument and the big push development literature. The latter has been demolished by practical experience: the list of its dismal failures is far too long. There are more than echoes of this discredited approach in the CEA document. It links to a paper that credulously recycles the old, bad, discredited theories.

What is amazing about the infant industry argument is how often it is invoked, and how little empirical evidence supports it. One of the few empirical papers, that of Krueger and Tuncer, rejects the argument in the case of Turkey.

A paper by Juhasz is often touted to support the theory. It shows that after the stimulus of the cotton spinning industry in France due to Napoleon’s Continental system, post-1815 the industry was competitive with the British, indicating that it had moved down the learning curve. Again, at most this identifies a necessary condition for protection–learning–but not a sufficient one. Even if LBD occurs, and even if there are spillovers, the cost of protection may exceed the benefits. A simple story demonstrates this. If the protected industry achieves cost parity with the first-mover (e.g., the UK in cotton), the protected firms merely displace firms in the first-mover country, leaving post-parity total costs unchanged. So in equilibrium, protection is costly but generates no benefits.

All in all, the CEA document reminds me of a rather conventional undergraduate econ paper, repeating textbook wisdom about externalities and market failures. It completely ignores the Coasean insight that market contracting methods are far more sophisticated than those in the textbooks, and that market participants have incentives to find clever ways to contract around what would be market failures if market transactions were limited to the forms considered in textbooks. It also ignores the historical record.

In other words, rather than writing off the difficulties of securing “bankable” contracts to secure funding for H2 developments to “market failures” or the excessive risk aversion of market participants, the government should step back and consider whether this alleged hesitation reflects a more sober and informed evaluation of risks than our betters in DC have undertaken.

I crack myself up sometimes.

In sum, the administration’s entire approach to hydrogen is utterly flawed. It attempts to pick technologies based on a pretense of knowledge it does not possess. It views flashing red lights warning of risks as signals to be suppressed rather than considered when making policy and investment choices. It engages in simplistic analyses of how real markets work, and how they have worked historically, to conclude that market failures requiring government intervention to fix abound in hydrogen.

All of these government failures could be eliminated by cutting the Gordion Knot, pricing carbon, and letting markets and private enterprise develop the technologies, products, contracting practices, and market mechanisms to trade off efficiently the benefits of reducing CO2 emissions. Decentralized mechanisms discover and utilize information, including information about new technologies, far more efficiently than governments. Decentralized mechanisms incentivize learning and innovation–including contracting and organizational innovations that can be instrumental in developing and adopting new technologies, products, and techniques.

In the case of hydrogen, pure or “contaminated” with carbon, priced carbon would address the problems that the CEA frets about, in particular the contracting problem. A carbon price would make it straightforward to index prices in contracts. A formula related to NG prices (because blue hydrogen is likely to drive the price of hydrogen at the margin, and because methane is likely to be the substitute at the margin for H2 in many applications) and the cost of carbon would send the appropriate signals and eliminate the need to fix prices in advance.

What the price of carbon should be and how it should be determined is a whole other question. But it would be far more productive, and not just in regards to hydrogen, to focus on that problem rather than leaving it to the John Kerrys of the world to pick technologies and then devise the coercive mechanisms necessary to force the adoption of those technologies.

Alas, we are on the latter path. And it will not take us to a good place. Probably figuratively, and perhaps literally, to the fate of the Hindenberg.

July 4, 2023

Salem and Gomorrah: America at 247

Today is Independence Day, but for me it is more an occasion of resignation (or melancholy even) than celebration, because the chasm separating the present America from that envisioned in the Declaration is vast, and growing by the day.

The bedrock ideals in the Declaration were individual liberty; emancipation from government tyranny; natural rights possessed by all individuals; and self-government. 247 years later, all of these ideals are widely scorned by the ruling classes, and are as a result are becoming progressively further from realization.

I use the word “progressively” deliberately: for progressivism–especially in its most current guise–is directly responsible for the assault on these ideals. 21st century progressives do not revere the ideals in the Declaration–they revile them. (And it has always been so for progressives–cf. Woodrow Wilson).

Individualism has been replaced by collectivism and identitarianism. Individualism is anathematized as white privilege, and the fact that those who met in Philadelphia in 1776 (and in 1787) were white, and in some cases held slaves, is considered proof of the illegitimacy–and indeed the evil–of the Founding.

The concept of natural rights possessed by all individuals equally is also an anathema to progressives, who elevate group and tribe over individuals, and who believe that members of some tribes are more equal than others, and have claims on others due to iniquities allegedly inflicted on the long dead members of one tribe by the long dead members of the other tribe. Guilt and punishment have become collectivized, and unmoored from individual conduct.

The 21st century state exercises vastly more tyrannical power over virtually every aspect of our lives than George III or Lord North could have even imagined in 1776. Relatedly, as for self-government, the colossus of the administrative state is almost totally unchecked by the branches of government that are supposed to be accountable to the people. Taxation without representation has been replaced by regulation (of the most minute details of our lives) without representation. Parliament on the Thames in the age of sail was never so remote to the average American as a regulatory agency on the Potomac in the days of the Internet.

The progressive march through the institutions, which began at the dawn of the 20th century, has accelerated greatly in the first quarter of the 21st. The institution with which I am most closely affiliated–academia–seems to me to be beyond saving. Tragically, an institution which has been of deep interest and importance to me–the US military–is on its way to joining academia as a lost cause.

I am tempted to say that these developments are un-American. But alas, although they are anti-American to the extent that “American” is identified with the ideals of the Founding, they are largely Made in the USA. A la Pogo, we have met the enemy, and he is us. Or at least, he is some of us, and that some hold the whip hand.

In many respects, as this article argues, progressivism–especially in its current Woke form–is just the current manifestation of the Puritanism which in many guises (including guises assumed by those who would consider themselves anything but puritanical) has been a catalyst for change and a source of social conflict in America for almost exactly 400 years. (I have made a similar point from time to time). And Puritanism is pretty damned American–or at least, has been a pretty damned important part of America from the first English colonization of the continent.

Like Puritanism, modern progressivism is extremely judgmental. It is Manichean. It is censorious. It divides people into the elect and the damned. It erects its own (now virtual) pillories. It ostracizes and banishes. It is uncompromising and unforgiving. It definitely does not believe in “live and let live.” It is prone to intense moral panics (cf. the Salem Witch Trials then, COVID or the Russians today). It is intensely self-righteous–and hence intensely hypocritical. Completely divorced from Calvinist religion, yes, but essentially Calvinist in spirit and mindset and conduct.

But it is worse than Calvinism qua Calvinism, because at least the original Calvinists had the fear of God in them, and thus from time to time had to question whether they really were doing God’s work. Modern progressives, secular to the core, have no God to fear and hence are immune from doubt. Meaning that they coerce without qualm. Indeed, they coerce with intense self-righteousness.

Mencken famously said that “Puritanism is the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” I don’t think that’s quite right. Puritanism is the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, is doing something to make the Puritan unhappy–combined with the conviction that the Puritan has the absolute right to find, root out, and punish this transgression. But Mencken’s formulation and mine share one very important implication: the Puritan doesn’t want to leave anyone alone.

And what is “the pursuit of happiness” other than the desire to be left alone to behave by his or her lights? That is something that Puritans old and new just cannot abide.

In its original incarnation, Puritanism contributed to the social dynamic that ultimately led to the Declaration of Independence. The Puritans came to American shores, of course, to escape English royal and religious tyranny, and thus had a spirit of independence that intersected in some ways with the spirit of independence from English tyranny that gave birth to the Revolution. But that historically contingent confluence of interests belies a fundamentally different conception of the meaning and political implications of the word “independence.”

21st century America can be described as Salem and Gomorrah. Hardly a happy combination, and certainly not a combination that Thomas Jefferson et al strove to achieve when they pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor 247 years ago today. Hence the mixed emotions which the Fourth of July evokes in this 21st century American. Reverence for what might have been, resignation at what has actually grown from the seed planted centuries ago.

June 29, 2023

Joe Phones It In . . . To Chinese, Russian, Iranian, Nork Intel?

There has been some attention paid to the apparent fact that Joe Biden had a private AT&T global phone paid for by one of Hunter’s companies–although not by the mainstream media of course. For the most part, the focus of the discussion of the phone has been on how it could play into investigations of whether The Big Guy was indeed a principal in The Crack & Hos Guy’s “business dealings” with dodgy foreigners. Not that that’s unimportant, but that misses another major, major disturbing–and gobsmacking–aspect of the story.

Specifically, reporter John Solomon claims to have called the number in question . . . and Joe Biden hisself answered the phone.

John Solomon is an American treasure.

— Big Fish (@BigFish3000) June 28, 2023

Busts Joe Biden on his secret global burner phone. pic.twitter.com/CfvFnq460t

This is insane and disturbing on many levels. Specifically, a phone like this represents a huge security risk–a risk that puts Trump locking some documents in Mar a Largo far, far in the shade. Phones can be hacked by intelligence agencies–remember the scandal when it was revealed that the Obama’s NSA had hacked Angela Merkel’s “handy”? This allows interception of calls and texts. Furthermore, intelligence agencies–including our golly gee whiz junior G-men at the FBI–are known to have the capability of turning phones into eavesdropping devices, meaning that there is a real possibility that the Chinese, the Russians, Iranians, Norks, and whoever have listened to highly sensitive conversations at which Biden was present (though they may pay no attention to Joe’s contributions to these confabs, for obvious reasons). And what about geolocation of the phone?

I’m sure Vladimir Putin is rolling his eyes at Joe–and rubbing his hands with glee.

How in the hell has the Secret Service permitted Geriatric Joe to be walking around with such a huge security risk?

But as insane as these things are, the most insane thing is that apparently Joe Biden answered a call from a stranger on this thing. How many calls from unknown numbers do you get a day? I get more than a few, and never ever answer them. I wonder how many scam calls Joe has taken! And it would even be worse if Biden knew that Solomon was calling, and knew who Solomon is: how could he possibly think answering would turn out well? I mean, how stupid can you get?

Some are calling BS on Solomon, and demanding he prove he spoke to Biden. Well, I guess there is some possibility that Solomon could be making this all up, but I doubt it. Doing so would put Solomon’s livelihood and reputation at extreme risk. Further, Solomon could prove with his own phone records that he made a call to that number and the duration of the call (which he says was short, due to Joe apparently having a ruh-roh moment).

Solomon should call for Biden to authorize disclosure of the geolocation data for the phone, along with official documentation of where Biden was at the time. If Joe was where the geolocation data says the phone was . . .

(For the record, I have “the data related to Biden’s phone will be ‘corrupted’ a la the J6 non-bomber’s phone” on my bingo card. Not a certainty, but a possibility.)

Of course Biden and those who do his thinking for him will never agree to this . . . because it would be a stunning admission of the security vulnerability the phone represents. But a refusal to comply should be taken as an admission.

Although Biden et al would not voluntarily take Solomon’s dare, James Comer’s committee should definitely subpoena the records from AT&T. And given the J6 Committee’s subpoenaing such phone records from government/executive branch officials–and the willingness of the phone companies to comply and the courts affirmation of the legitimacy of the subpoenas–the committee has every right to do so and to expect compliance.

Wouldn’t that be fun!

One can only imagine the media and political hysterics had Trump done this. But the media continues to play the Dutch Boy and the Dike (that’s with an “i”, people) on this and most of the rest of the Biden corruption-related allegations. So many leaks–literal and figurative–are now springing, however, that it is doubtful that the media and the administration can plug them all despite their valiant efforts. The phone could be the one that is too big to plug. And even beyond its implications for corruption investigations, it provides a stunning glimpse into Biden’s shockingly cavalier attitude towards security (despite his tut-tutting about Trump’s), and the Secret Service’s complicity in allowing it to happen.

June 24, 2023

The Wagner Putsch: Kornilov Redux or Something More Threatening?

The news of the day is that Yevgeny Prigozhin has reversed direction, and instead of attacking Ukraine has occupied Rostov-on-the-Don and Veronehz, and has advanced some distance into the Moscow Oblast in an attempted putsch. As in all things Russian, good information is hard to come by–and the Russian authorities are doing their best to shut down all non-official “information” sources.

Prigozhin launched a broadside against Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and the military chief of staff Valery Gerasimov. In a version of the old “the tsar doesn’t know and is being misled by bad boyars” trope, Progozhin claims that this pair of mouth breathers deceived Putin about the need for an invasion of Ukraine and the ease of accomplishing it, and continue to deceive him by downplaying casualty figure. This is a transparent attempt to claim–incredibly–that this action is directed against Putin. Since Putin is the only man who matters, any challenge to the state is a challenge to Putin.

There are reports of combat between Prigozhin’s Wagner forces and the Russian military, with the former claiming to have shot down several military helicopters and at least one SU-34. There are also reports that some Russian military and national guard forces have thrown in with Wagner, or stood aside.

Some analysts claim that Wagner represents a real military threat to Putin. The conventional wisdom is that it does not: on the BBC Mark Galeotti claimed that Wagner has only 10,000 men at his disposal. But information is scarce, everything is in flux, and there is always the prospect that enough military and security force commanders are so disenchanted with the Ukraine fiasco that they will start supporting Wagner, or refuse orders to attack it, or block other units from doing so.

The most recent reports, from less than reliable sources (such as the Belarussian administration), are that Prigozhin has agreed to return to barracks. Which would be suicidal unless he has some sort of ironclad deal.

The fact is that the die is cast. Prigozhin made his choice and he must win or die. Any pause will be a tactical one.

My conjecture is that Prigozhin has known for some time that Shoigu and Gerasimov and the rest of the establishment intend to eliminate him and Wagner with extreme prejudice. The “sign a contract or else” ultimatum was just setting up the legal justifications for such an action.

Given that, Prigozhin was desperate, and had to throw the dice. He had nothing to lose.

The uncertainties in a situation like this make prediction perilous. If I had to guess, I wold say that this will play out something like the pathetic Kornilov Affair in 1917, when the eponymous general marched on the capital (then St. Petersburg) in an attempted coup against the Kerensky government. (Though some claim that Kerensky was part of the plot–and not surprisingly I have seen some claim that Putin is actually in cahoots with Prigozhin.) The coup attempt collapsed within 3 days.

But you never know.

As for Putin, this morning he gave a fiery speech denouncing the putsch and promising that it would be crushed. In so doing, Vova treated us to some of his Fractured Fairy Tale history:

A blow like this was dealt to Russia in 1917, when the country was fighting in World War I. But the victory was stolen from it: intrigues, squabbles and politicking behind the backs of the army and the nation turned into the greatest turmoil, the destruction of the army and the collapse of the state, and the loss of vast territories, ultimately leading to the tragedy of the civil war.

For one thing, Russia was hardly on the verge of victory in 1917. In fact, its army was teetering on the edge of collapse–and at times did collapse. Widespread desertion and mutiny contributed to the crisis that culminated in the abdication of Nicholas II. After something of a recovery following the February Revolution, the collapse of the military resumed after the utter failure of the Kerensky Offensive. And vast territories had already been lost by 1917.

For another thing. Wait, whut? The Putin I know lamented the fall of the USSR as the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the 20th century. This Putin–is he an imposter?–is lamenting the revolution that resulted in the creation of the USSR. Just another illustration, I guess, that to Putin history is purely instrumental, meant to be distorted to meet the needs of the political moment.

Although who will win in Russia is in doubt, there is no doubt that the biggest winner here is Ukraine. Chaos at the top will distract the Russian military leadership from managing operations in Ukraine. If the Wagner threat persists Putin will have to divert units from fighting Ukrainians to fight Russians.

Regardless of how this plays out, it is a clear sign that all is not well in Putin’s Russia. In fact, things are quite bad. Some natives are restless–and with good cause. Meaning that Putin is confronted with a war on two fronts, precisely when experience has shown that he is incapable of handling just one.

June 17, 2023

A Near Run Thing On the Steppes

So the long-awaited Ukrainian counteroffensive has begun. How’s it going? Who knows?

Initial reports indicate that the Ukrainians have made advances measured in kilometers, but not tens of kilometers, in several areas along the long front. They have suffered losses in armor and of course personnel, but how much is hard to gauge. The Russians have crowed about inflicting large material losses, but showing the same damaged Leopard tank from several angles rather dilutes their boasts.

Regardless, this is hardly Guderian racing to the Channel coast, Patton rampaging from Normandy to Paris to Metz, or the USMC breaching Iraqi prepared defenses and reaching Kuwait City long ahead of schedule. But does that mean anything? Again, who knows?

For one thing, the above are exceptions rather than rules when it comes to offensives, so one should not benchmark Ukraine’s efforts against them. For another, it is still unknown whether this represents the main Ukrainian effort, or is instead probing attacks, or feints, or shaping operations, or initial grinding assaults intended to gnaw through prepared Russian defenses thereby opening gaps through which the main Ukrainian assault forces can pour into the Russian rear areas.

In preparation for the Ukrainian assault, the Russians have constructed multiple lines of defense, with the approaches heavily–and I mean heavily–mined. (Where’s Princess Diana???) Getting through the minefields is a major challenge, and the necessarily slow pace of doing so subjects the attacker to artillery bombardment and air strikes. So the going can expected to be tough, with high casualties.

One model that comes to mind is El Alamein. Rommel had entrenched along the Egyptian border, and sowed massive minefields. When Montgomery attacked, it was extremely slow going at first, with large casualties in personnel and armor. It took about 10 days for British (mainly ANZAC and South African, actually) infantry to clear pathways through the minefields through which British armor could eventually pass. During the 3 week battle, Montgomery shifted the weight of his advance from the right flank to the left and back again as one flank became bogged down. It was a long, slow process, but once the British had gnawed through the prepared defenses, at high cost, Rommel was forced to withdraw, thus beginning a race westwards through Libya and back to Tunisia.

The Normandy campaign is another. Weeks of bitter combat with Allied forces attempting to break through German lines, measuring progress in yards, if that, eventually resulting in breakout at St. Lo and a precipitous German withdrawal to the Seine and beyond.

Today, the Russians have some advantages the Germans lacked. In particular, they have an edge in the air, whereas the British did in 1942 and the Allies did in 1944: the breakout at St. Lo in Operation Cobra was made possible by a massive air bombardment that wrecked and stunned the already heavily attrited Panzer Lehr division–and also killed a lot of Americans hit by “shorts.” After being an non-factor during offensive operations, Russian attack helos have apparently been effective in the defense against the counter offensive. Russian fixed wing aviation has also made itself felt in contrast to its performance heretofore. Ukraine has no ability to execute the equivalent of a Cobra.

That said, German troops were far better than the Russians are–and maybe even the derided Italians in the desert were better than the mobiks currently absorbing blows.

The Ukrainians have advantages in night fighting capability, and that can be decisive. But it’s hard enough to breach minefields in the day, let alone at night. So the night fighting advantage can’t be decisive until the minefields have been breached and the Ukrainians can close with the Russian defenders–assuming, of course, that the Russians stand if the Ukrainians do make a breach or breaches and start running amok in the Russian rear.

So as of now, uncertainty reigns. Uncertainty regarding the Ukrainian operational plan (e.g., is this their main effort, or a shaping operation?) Uncertainty regarding what is actually transpiring on the battlefield. Uncertainty regarding the combat power and endurance of the contending forces.

The advantage of the offense is that it is only necessary to break through in one place to achieve a decisive victory–provided the attacker has highly mobile reserves to exploit a breakthrough and the defender doesn’t have the mobile reserves (and especially mobile reserves led the by likes of a von Manstein or a Model) to seal the breach. It remains to be seen whether the Ukrainians have the ability to break through, and more importantly, the force to exploit a breach if they do. Several Russian counterattacks have apparently been repulsed quite bloodily (wrecking an entire division in one instance), and based on prior performance and the attrition of the past months I seriously doubt whether they can execute a mobile defense if their lines are breached anywhere–or even if Putin will let them. The necessity of deploying over a very long front extending hundreds of kilometers combined with the pronounced lack of skill at combined arms mobile warfare suggests that a Ukrainian breach anywhere would be devastating to the Russians. But whether Ukraine can achieve that breach before culmination is a very open question.

So I predict that the race between Ukrainian counteroffensive and the Russian defense will be like how Wellington described Waterloo: “the nearest run thing you ever saw.”

June 7, 2023

Drive a Stake Through the Heart of Stakeholder “Capitalism” Before It Is Too Late

The recent controversies embroiling many corporations, notably Target, Disney, and Imbev (the owner of Anheuser-Busch) has brought the issue of stakeholder “capitalism”* to the center of American political discourse. These controversies demonstrate clearly why corporations and their executives should not indulge their own preferences or preferences of “stakeholders” other than shareholders, but should instead limit their efforts to what is already a very demanding task–maximizing shareholder value.

At its root, stakeholder capitalism represents a rejection–and usually an explicit one–of shareholder wealth maximization as the sole objective and duty of a corporation’s management. Instead, managers are empowered and encouraged to pursue a variety of agendas that do not promote and are usually inimical to maximizing value to shareholders. These agendas are usually broadly social in nature intended to benefit various non-shareholder groups, some of which may be very narrow (transsexuals) or others which may be all encompassing (all inhabitants of planet earth, human and non-human).

This system, such as it is, founders on two very fundamental problems: the Knowledge Problem and agency problems.

The Knowledge Problem is that no single agent possesses the information required to achieve any goal–even if universally accepted. For example, even if reducing the risk of global temperature increases was broadly agreed upon as a goal, the information required to determine how to do so efficiently is vast as to be unknowable. What are the benefits of a reduction in global temperature by X degrees? The whole panic about global warming stems from its alleged impact on every aspect of life on earth–who can possibly understand anything so complex? And there are trade-offs: reducing temperature involves cost. The cost varies by the mix of measures adopted–the number of components of the mix is also vast, and evaluating costs is again beyond the capabilities of any human, no matter how smart, how informed, and how lavishly equipped with computational power. (Daron Acemoğlu, take heed).

So what do climate-concerned executives do? Adopt simplistic goals–Net zero! Adopt simplistic solutions–deprive fossil fuel companies of capital!

Maximizing shareholder value is informationally taxing enough as it is. Pursuing “social justice” and saving the planet is vastly, vastly more so.

Meaning that even if corporate executives were benevolent–a dubious proposition, but put that aside for now–they would no more possess the information necessary to pursue their benevolence that does a benevolent social planner.

Instead, executives pursuing non-shareholder wealth objectives are almost certain to be Sorcerer’s Apprentices, believing they are doing right but creating havoc instead.

Agency problems exist when due to information asymmetries or other considerations, agents may act in their own interests and to the detriment of the interests of their principals. In a simple example, the owner of a QuickieMart may not be able to monitor whether his late-shift employee is sufficiently diligent in preventing shoplifting, or exerts appropriate effort in cleaning the restrooms and so on. In the corporate world, the agency problem is one of incentives. The executives of a corporation with myriad shareholders may have considerable freedom to pursue their own interests using the shareholders’ money because any individual shareholder has little incentive to monitor and police the manager: other shareholders benefit from, and thus can free ride on, any individual’s efforts. So managers can, and often do, get away with extravagant waste of the resources owned by others placed in their control.

This agency problem is one of the costs of public corporations with diffuse ownership: this form of organization survives because the benefits of diversification (i.e., better allocation of risk) outweigh these costs. But agency costs exist, and increasing the scope of managerial discretion to, say, saving the world or achieving social justice inevitably increases these costs: with such increased scope, executives have more ways to waste shareholder wealth–and may even get rewarded for it through, say, glowing publicity and other non-pecuniary rewards (like ego gratification–“Look! I’m saving the world! Aren’t I wonderful?”)

Indeed, we now have a highly leveraged agency problem, due to the ability of asset managers like Black Rock to vote the shares of their customers, thereby allowing the likes of Larry Fink to force not just one corporation to indulge his preferences, but hundreds if not thousands. Larry Fink and his ilk can influence the direction of sums of capital dwarfing anything in history to pursue their agendas.

The agency problem pervades stakeholder capitalism even when you dispense with the idea that the shareholders are the principals, and expand the set of principals to include non-shareholder interests (which is inherently what “stakeholder” capitalism means). And as discussed above, in stakeholder capitalism these interests conceivably encompass all life on earth.

The problem is that just as shareholders are diffuse and cannot prevent managers from acting in their interest, stakeholders are often diffuse too. And in the case of climate, All Life On Earth is about as diffuse as you can get. Furthermore, whereas at least in principle shareholders can largely agree that the firm should maximize their wealth, when one expands the set of interests, these interests will inevitably conflict.

So what happens? Just as in politics and regulation, small, cohesive minority groups who can organize at low cost will exert vastly disproportionate influence. It is not surprising, therefore, that companies like Target (to name just one) have responded to the interests of transsexuals–a decidedly narrow minority group–and given the finger to others who should be “stakeholders” as well, namely customers. Customers being a diffuse, dispersed, heterogeneous group that is costly to organize–precisely for the same reasons that it is costly for shareholders to organize.

(The Target and Bud Light episodes suggest that social media has reduced the costs of organizing diffuse groups, but even so, it is far costlier to do that than to organize ideological minorities.)

In other words, stakeholder capitalism inevitably creates a tyranny of minorities, and especially highly ideological minorities (because a shared ideology reduces the cost of organizing). Minority stakeholders will succeed in expropriating majority ones.

Minority tyranny is the big problem with democratic politics. Extending it to vast swathes of economic life is a nightmare.

So what is stakeholder capitalism, when you get down to it? A world of Sorcerer’s Apprentice executives (the Knowledge Problem) with bad incentives (the agency problem).

Other than that, it’s great!

Some libertarians have a peculiar take on this phenomenon. They view stakeholder capitalism as benign, because it is undertaken by private actors, rather than the government.

This take is gravely mistaken. It ignores fundamental principle, and commits at least two category errors.

The forgotten principle is that a liberal society should aim to minimize coercion.

The first category error is to believe that private actors cannot coerce–only governments can. In fact, private actors–including corporations and their managements–can clearly coerce. Come and see the violence inherent in the stakeholder capitalism system straight from the mouth of its primary exponent:

BlackRock CEO: “At BlackRock we are forcing behaviors… you have to force behaviors.” pic.twitter.com/2Q2H84GPC7

— TexasLindsay(@TexasLindsay_) June 4, 2023

“We are forcing behaviors.” Coercive enough for you? Help, help, I’m being repressed:

That bit, by the way, concisely expresses the stakeholder capitalism movement, right down to the “shut up!” and “you bloody peasant!”

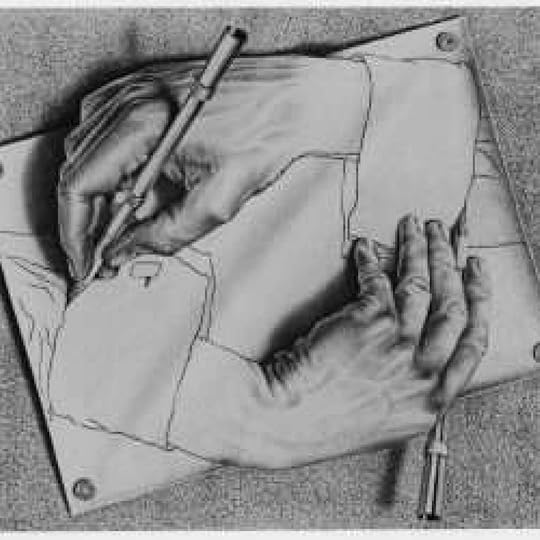

The second category error is to believe that there is some sort of clear boundary between private entities (corporations especially) and governments. In fact, the true picture is like the Escher Hands:

Corporations influence government. Government influences corporations (cf., Twitter Files, etc.–the examples are almost endless). Governments often outsource coercion to corporations. Corporations induce the government to coerce for their benefit–and to the detriment of alleged “stakeholders” like customers, labor, and competitors.

Furthermore, as the Arrow Impossibility Theorem teaches, any coherent social welfare function (i.e., any theory of social justice) is inherently dictatorial, and thus inherently coercive. Thus, to the extent that stakeholder capitalism is intended to implement any particular vision of social justice, it is necessarily dictatorial, and hence coercive. It is antithetical to a liberal system like that envisioned by Hayek, that is, one in which a set of general rules is established under which people can pursue their own, inevitably conflicting, aspirations. (Less formally than Arrow, Hayek also argued that any system of social justice is inherently coercive and dictatorial.)

Stakeholder capitalism is therefore a truly malign movement, and an anathema to liberal principles. We need to drive a stake through its heart, before it stakes us to the ant hill.

*I put “capitalism” in quotes because stakeholder capitalism is an oxymoron. Recall that capitalism is an epithet devised by Marx to describe a system ruled in the interests of capital, i.e., shareholders. Stakeholder capitalism is a system intended to be ruled in the interest of everyone but capital. Hence the oxymoron.

** Jeffrey Tucker has also eloquently and rightly excoriated the response of many libertarians to COVID. Here again, these libertarians forgot that limiting coercion is the bedrock libertarian principle.

*

June 6, 2023

Stop Me If You’ve Heard This Before: Those Damned Speculators Are Screwing Up the Oil Market!

Saudi Arabia is fussed at the low level of oil prices. So true to form with those unsatisfied with price, they are rounding up the usual suspects. Or in this case, suspect–speculators!

I’m sure you never saw that coming, right?

As the world’s biggest oil producers gather here Sunday to decide on a production plan, the spotlight is on the cartel kingpin’s fixation on Wall Street short sellers. Abdulaziz has lashed out repeatedly this year against traders whose bets can cause prices to fall. Last week he warned them to “watch out,” which some analysts saw as an indication that the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies may reduce output at their June 4 meeting. A production cut of up to 1 million barrels a day is on the table, delegates said Saturday.

Claude Rains is beaming, somewhere.

I’m so old that I remember when oil prices were beginning their upward spiral in 2007-8 (peaking in early-July), in an attempt to deflect attention from OPEC and Saudi Arabia, one of Abdulaziz’s predecessors blamed the price rise on speculators too.

Is there anything they can’t do?

Not that I’m conceding that speculators systematically or routinely cause the price of anything to be “too high” or “too low,” but if you do think that they influence price, they should be Abdulaziz’s best buddies. After all, they are net long now and almost always are. (Cf. CFTC Commitment of Traders Reports.)

If the Saudis (and other OPEC+ members) have a beef with anybody, it is with their supposed ally, Russia. Russia had supposedly agreed to cut output in order to maintain prices, but strangely enough, there is no evidence of reductions in Russian supplies reaching the world market, even despite price caps on Russian oil and the fact that they are selling it at a steep discount to non-Russian oil. Perhaps Russia has really cut output, but (a) that doesn’t really boost the world oil price if Russian exports haven’t been cut, and (b) it would mean that Russian domestic consumption is down, which would contradict Moscow’s narrative that the economy is hunky-dory, and relatively unscathed by sanctions.

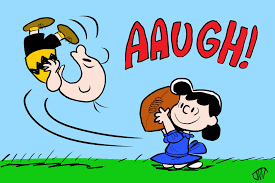

But I think that the more likely story is that Russia is playing Lucy and the football with OPEC.

Which would be a return to form: see my posts from years ago. And I mean years ago. Apparently Won’t Get Fooled Again isn’t on Abdulaziz’s play list.

The other culprit behind lower oil prices is China: its tepid recovery is weighing on all commodity prices–not just oil. A fact that Abdulaziz should be able to understand.

But it’s much easier to shoot the messenger, and that’s what speculators are now–and almost always are. Venting at them probably makes Abdulaziz feel better, but even if he were to get his way that wouldn’t change the fundamental situation a whit.

Bashing speculators is what people who don’t like the price do. And since there’s always someone who doesn’t like the price (consumers when it’s high, producers when it’s low) bashing speculators has been and will continue to be the longest running show in finance and markets.

May 30, 2023

I Sorta Agree With Jerome Powell and Gary Genlser on Something: Sign of the Impending Apocalypse?

The Fed and the SEC have expressed concerns about Treasury “basis trades” wherein a firm purchases a cash Treasury security funded by repo-ing it out and sells Treasury futures. Their concern is somewhat justified. As mentioned in the linked article, and analyzed in detail in my paper in the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance (“Apocalypse Averted“) the spike in the cash-futures Treasury basis caused by COVID (or more accurately, the policy response to COVID) caused a liquidity crisis. The sharp basis change led to big margin calls (thereby creating a demand for liquidity) and also set off a feedback loop: the unwinding of positions exacerbated the basis shock, and thereby reinforced the liquidity shock.

This is just an example of the inherent systemic risk created by margining, collateralization, and leverage. The issue is not a particular trade per se–it is an inherent feature of a large swathe of trades and instruments. What made the basis trade a big issue in March 2020 was its magnitude. And per the article, it has become big again.

This is not a surprise. Treasuries are a big market, and leveraging a small arb pickup is what hedge funds and other speculators do. It is a picking-up-nickels-in-front-of-a-steamroller kind of trade. It’s usually modestly profitable, but when it goes bad, it goes really bad.

All that said, the article is full of typical harum-scarum. It says the trade is “opaque and risky.” I just discussed the risks, and its not particularly opaque. That is, the “shadowy” of the title is an exaggeration. It has been a well-known part of the Treasury market since Treasury futures were born. Hell, there’s a book about it: first edition in 1989.

Although GiGi is not wrong that basis trades can pose a systemic risk, he too engages in harum-scarum, and flogs his usual nostrums–which ironically could make the situation worse:

“There’s a risk in our capital markets today about the availability of relatively low margin — or even zero margin — funding to large, macro hedge funds,” said Gensler, in response to a Bloomberg News inquiry about the rise of the investing style.

Zero margin? Really? Is there anyone–especially a hedge fund–that can repo Treasuries with zero haircut? (A haircut–borrowing say $99 on $100 in collateral is effectively margin). And how exactly do you trade Treasury futures without a margin?

As for nostrums, “The SEC has been seeking to push more hedge-fund Treasury trades into central clearinghouses.” Er, that would exacerbate the problem, not mitigate it.

Recall that it was the increase in margins and variation margins on Treasury futures, and the increased haircuts on Treasuries, that generated the liquidity shock that the Fed addressed by a massive increase in liquidity supply–the overhang of which lasted beyond the immediate crisis and laid the groundwork for both the inflationary surge and the problems at banks like SVB.

Central clearing of cash Treasuries layers on another potential source of liquidity demand–and liquidity demand shocks. That increases the potential for systemic shocks, rather than reduces it.

In other words, even after all these years, GiGi hasn’t grasped the systemic risks inherent in clearing, and still sees it as a systemic risk panacea.

In other words, even though I agree with Gensler (and the Fed) that basis trades are a source of systemic risk that warrant watching, I disagree enough with GiGi on this issue that the apocalypse that could result from our complete agreement on anything will be averted–without the intervention of the Fed.

May 21, 2023

Reading the US Government CDS Tea Leaves

As the periodic debt ceiling game of chicken proceeds, you might read about the credit default swap (CDS) rate on US government debt. This is commonly (even by economists) used to quantify the market’s estimate of probability that the US government will default. Although it is related to this probability, it is not a direct measure of the “true” probability. So interpret with extreme care. Especially in the case of US government debt.

As a little background, a CDS is a contract that pays off if the underlying entity–in this case, the US government–defaults on its obligations. In that event, the purchaser of protection receives the face value of the debt minus the price of the defaulted security. If the defaulted security is worth 40 cents on the dollar at default, the “recovery rate” is 40 percent and the protection buyer receives 60 cents on the dollar.

If the protection currently costs X, you might reason that your expected payoff is p(1-R), where p is the probability of default and R is the recovery rate. Thus, you can estimate p=X/(1-R).

The problem with this logic is that p is not the real world–“physical measure” or “true”–probability of default. It is the probability of default in the so-called “equivalent measure.” Roughly speaking, this p includes a risk adjustment, a risk premium if you will. In theory the p estimated this way could be less than the actual probability of default, meaning that the premium is negative. But usually the p implied this way will be above the objective probability of default. Put simply, just like when you insure your car you will pay a premium that exceeds your expected claims, with CDS the protection purchaser will pay a premium that exceeds the expected payoff.

Indeed, the risk premium embedded in Treasury CDS is likely to be quite large. The reason is that this type of CDS will pay off in bad states of the world–and likely very bad states of the world. That is, if the US government defaults, economic chaos and a recession (perhaps a severe one) is a likely outcome. The marginal utility of income (or wealth) is high when income (or wealth) is low, as during a large recession. Thus, protection sellers are required to perform on their contracts when the marginal utility of income/wealth is higher, so they are going to charge a high price in order to assume such an obligation. The worse the economic consequences of default, the higher the risk premium, and hence the price, that they will charge.

That is, the USG CDS price must exceed the expected payout, likely by a lot, because the payouts occur in bad economic times.

Corporate CDS spreads tend to be “upward biased” measures of default rates for companies, precisely because payoffs tend to be more likely during bad economic times because that’s when companies default. This bias is likely to be especially great for USD CDS precisely because a default will likely cause a severe economic contraction.

Another way to visualize this is to realize that there is considerable “systematic risk” in USG CDS. The risk in CDS payouts cannot be diversified away, and are highly correlated with the overall financial markets. Put differently, a US government default is not really an insurable risk. Classic insurance works by diversification and pooling of independent risks. That is not possible with USG CDS.

There’s another factor at play here–counterparty risk. How much would you pay for insurance from a financially shaky insurance company? Probably not much, because it may not be around to pay when you need it.

Since a US government default is likely to have severe consequences for the financial sector, there is a material probability that the seller of protection will be unable to perform in the event of a USG default.

This would tend to work in the opposite way as the risk adjustment described earlier, that is, it would tend to reduce the cost of protection. The protection is worth less because of the risk it would not be there when you need it. This reduces your willingness to pay for it.

These risk adjustment and counterparty risk issues are likely to be particularly acute for US Treasuries, given the potentially serious economic consequences of a government default. Meaning that USG CDS rates are very unreliable measures of the likelihood of a government default: they are impacted by both the probability of default and the economic consequences thereof.

Yes, a rising CDS spread–like we’ve seen recently–likely reflects a rising estimate of the true probability of a default. But you just can’t back out that probability from the rate.

May 19, 2023

In the Military DIE (and Other Progressive Ideologies) means DIE

I’m often tempted to say that those in charge of our military are not serious people. But I catch myself. They are in fact very, very serious people–the problem is that they are serious about agendas that are inimical to military effectiveness and national defense.

The most virulently inimical agendas is of course DIE. The current Air Force Chief of Staff, Charles Q. Brown–leading candidate to be JCS Chair–is perhaps the most egregious example. Brown is a quota monger:

The topic of the Air Force memorandum was officer quotas set by race and gender.

Similar quotas had been issued by political appointees in a politically correct military, but they had focused on slowly boosting minority officers rather than calling for a purge of white men.

The 2014 quotas had looked for an 80 percent white, 10 percent black and 8 percent Asian officer corps. While choosing officers by any racial category rather than merit is racist, wrong and illegal under civil rights legislation, this fell short of Brown’s proposed racist purge.

Brown’s quotas limit the number of white officers to 67% and cut white men down to 43%.

The Air Force officer corps is currently 77% white: getting it down to 67%, a reduction of 10%, would require serious effort to purge white officers and bar the doors to any new ones.

That will improve military effectiveness how, exactly?

A recent AF “experiment” suggests that “how much” is a negative number:

As part of the larger military-wide effort to promote diversity in the service’s pilot ranks, the 19th Air Force command near San Antonio, Texas, “clustered” racial minorities and female trainees into one class, dubbed “America’s Class,” to find out if doing so would improve the pilots’ graduation rates. However, not only did the effort fail to boost minority and women candidates’ success rates, but officers involved say they were ordered to engage in potentially unlawful discrimination by excluding white males from the class, documents show.

Excluding white males will help how, exactly? Specifically, how will it build unit cohesion?

Obviously, it won’t. It is inimical to unit cohesion. Military units need to suppress differences to succeed, not accentuate and emphasize them. I mean, I can’t even.

What was traditional boot camp all about? Suppressing individual differences. Making everyone believe he was just a soldier or a sailor or a Marine. One of thousands.

Some of the quotes in the Front Page article just leave me shaking my head:

“I am a Black man who happens to be the Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force,” Kaleth Wright, now retired, had tweeted “You don’t know the anxiety, the despair, the heartache, the fear, the rage and the disappointment that comes with living in this country… every single day.”

Uhm, you have reached the highest enlisted rank in the US Air Force. Yeah, I’m sure that happens a lot in racist countries. Damned white supremacism.

Or this:

Anthony Cotton, the Commander of US Strategic Command, had claimed that, “when I see what happened to Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks—and the list goes on and on… that could be me.”

No, General-Successor-of-Curtis-Lemay, it couldn’t be you. What would be more likely to be you is the 10,000+ blacks murdered in Chicago, Philly, DC, St. Louis, etc., etc., etc. Why don’t you talk about that? Why don’t you do something about that.

There’s also a vignette in the article about Brown whining about the cosmic injustice of being questioned about a parking spot.

Three people who are living proof of the lack of discrimination against blacks in the Air Force whining about how oppressed they are.

But this should not be surprising. Today, victimhood is status, and people compete intensely to prove how victimized they are, rather than to count the blessings that they have. Just another of the fucked up aspects of 2020s US culture.

Another illustration of the Diversity Cult: Air Force Assistant Secretary for Manpower and Reserve Affairs Alex Wagner proves–PROVES I TELLS YA–the power of diversity. Because of diversity, the AF avoided the incredible faux pas of handing out the wrong kind of socks as swag at SXSW! OMG! To think that the fate of the country’s defenses were rescued by such a brave woman!

Air Force Assistant Secretary for Manpower and Reserve Affairs Alex Wagner, shares a personal story about socks…yes socks… to explain why the military needs Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI).

— Charlie Kirk (@charliekirk11) March 24, 2023

We are not a serious country. pic.twitter.com/HYKJ7qbRXV

But how does diversity help when the shit really goes down, Alex? Can you give me an example of that? I’d say I wait, but I’m not into reenacting Waiting For Godot.

(As an aside, recruiting at SXSW is itself a testament to idiocy and cluelessness. It’s leftish, hipster central.)

The repeated invocations of the benefits of diversity, like Wagner’s, are catechisms. Statements of a faith. NOT empirical truths. In fact, social science research (since at least Putnam) suggests the opposite: diversity undermines trust. And there is no environment where trust is more essential than in battle. None.

I could go on.

And then of course there’s the trans obsession in the military, e.g., the Navy thinking that a drag queen is totes what is needed to rescue plummeting recruiting numbers:

I guarantee, even if it does boost recruiting numbers, it will reduce the number of recruits that the Navy should want to attract: it would be subtraction by addition.

FFS, couldn’t they have just rebooted the Village People?

Again, I could go on. . .

And there’s the green angle. And no, I don’t mean green as in the Marines are the mean green machine. No–green as in environmentalism, and specifically the climate change cult.

I’ve written before about the SECNAV prioritizing climate change. (How will that beat China, Mr. Del Toro?) But it’s a Whole of Government effort. For example, the Energy Secretary, Canadian-born Jennifer Granholm, endorsed Joe Biden’s pledge to make all US military vehicles electric by 3030. Sorry! Sorry! By 2030.

This idea is cosmically stupid on more dimensions than I could possibly explore in a lifetime–even if I was 40 years younger.

Say, just how big and heavy would a battery on an M1AE (for electric!) Abrams have to be? And, pardon my impertinence, but how would you charge it, exactly? And boy won’t it be fun for the crew when that sucker gets hit and cooks off!

Again, I could go on . . .

Although the exempli gratia are virtually endless, I think you get the point. Those in charge of the US military are serious about just about everything except fighting and winning wars.

Meanwhile, recruiting is in the toilet and the Navy is a shitshow.

If the shit does get real, these termite years of race and gender and climate obsessives will result in the loss of wars, and mass casualties.

But the corpses (especially the officers’) will be diverse. And isn’t that what really matters?

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers