Jonathan Ball's Blog, page 52

March 9, 2015

Having Too Many Ideas

Beginning writers often worry about ideas. The question “Where do you get your ideas?” has become a cliché, a question writers hate to answer, and the reason everyone hates it so much is this: non-beginning writers know that “getting ideas” is the easiest thing about writing. The difficulty, if you write regularly, is not getting ideas, but having too many ideas.

Having too many ideas may seem like a luxurious problem, but in fact it delivers to the serious writer a number of difficult challenges:

You have to select which ideas you will pursue. You won’t have time to write all the stuff you want, and realize all of your ideas — not even all of your great ideas. This is a hard concept for beginning writers with few ideas to wrap their heads around. After you start writing with some regularity, ideas are not the issue — time is the issue. There isn’t enough time in the world to realize all of your good ideas.

You must accept that you will let good ideas die. The darker side of the previous point is that you also have to decide which ideas you will never pursue. You have to become comfortable with letting not just most of your ideas die, but most of your excellent ideas.

You have to commit to a project. The temptation, when you have many ideas in front of you, is to work on one until it begins to get tiring or difficult, and then shift gears and work on a different project. Writers that do this have difficulty finishing projects. They may make progress on many projects at once, but often feel like they are getting nowhere, that they have very little to show for their tremendous efforts.

You must therefore sift good ideas from bad ideas, and then rank or prioritize your ideas. This is easier said than done, for reasons that will soon become apparent.

I want to examine the third problem in this post, while touching on the fourth problem — how do you pick a project from your lengthy list of ideas, commit to it, and finish it?

Evaluating Ideas

One of the problems with evaluating ideas is that the quality of the idea is somewhat insignificant. You can create a good piece of writing from a bad idea, and a bad piece of writing from a good idea. You can even create a masterpiece from a bad idea, like Shakespeare did with Hamlet (one of the worst, most disorganized plots of any Shakespeare play, and yet what I consider his best play).

Your enthusiasm for an idea is also somewhat irrelevant. Your enthusiasm will flag. What will get you through the terrible slumps — and there may be many — when you hate your idea? Only discipline and commitment.

You may be tempted to think through career or market possibilities. This is always a mistake. Nobody knows what will sell this week. Nobody knows what will sell next week. Sometimes I meet writers who talk about jumping on some trend to make money. When the parade is marching down your street, it is already too late to join the parade. You cannot anticipate trends, you can only be swept up in them. If you already had a vampire novel out, or about to come out, when Twilight hit, then the trend might have worked for you.

Similarly, if you are making decisions about what to write based on some vague notion of what the market expects, you will simply sand the rough edges off of your idea — thus eliminating everything that made it a good idea in the first place.

There is no real way to evaluate ideas in terms of their intrinsic value, since they have none. However, you can evaluate ideas in terms of how useful they might be to you, by asking a few questions of each idea.

How has it been done before? Almost every idea has been done before. You may need to do some research to determine what lives your ideas have previously lived. This will help you refine the ideas, to develop them in light of their previous incarnations, and make them more “yours.” You may also decide to abandon your idea after realizing it is far less original than you imagined. Research also has the benefit of giving you new, and often better ideas.

Do you think you can do it? If you are confident in your ability to take an idea from conception to completion, then you might want to abandon that idea. When you don’t have to stretch to pursue your ideas, they may end up boring you, and they won’t build your writing muscle. If you want to develop as a writer, you need to tackle ideas that force you to risk something creatively. The more difficult writing becomes, the more rewards you will see when you finally solve your creative problems.

Will this idea generate more ideas? What you really need from an idea is the potential to generate new ideas — a work of art is the culmination of an entire creative process, during which you will need to be generating and discarding and developing a variety of ideas. Sometimes, you will hit on an idea so strong that it is like a miniature idea factory: when that happens, you might have a concept on your hands, an idea that might give birth to and structure to some larger project. That’s what happened to me with Clockfire — I had an idea that I started investigating and developing, and it blossomed into a book.

One simpler way to evaluate ideas is to try to forget about them. If you can’t — if it has been years, and you still keep coming back to the same idea — then maybe there is something in that idea, and maybe you should commit to it.

I usually don’t pursue or begin writing anything (other than notes and a few lines) until I have let a few years pass, and then only if the idea still seems worth pursuing. For some writers, this means creative death. They mourn their lost ideas, which they did not pursue.

I love when my ideas die. This is a simple method of weeding out weak ideas that don’t even interest me for very long, after the initial shine of their newness has worn off.

Committing to a Project

After you have evaluated your many ideas and discarded most of them, you will still have too many ideas. You will still need to start prioritizing them and committing to a select few. A few factors come into play, and can help you decide what projects deserve your commitment:

External pressures. If you have been given a deadline for a project, then you should prioritize and commit to it. This might be obvious, but I still find myself procrastinating and pursuing more enjoyable projects. Conversely, you have to be careful not to get caught up in the treadmill of your deadlines. You will find yourself completing a lot of minor projects that other people have assigned to you, and not making progress on your large projects. More on this below.

Projects that live multiple lives. Some of your projects will go further than others, and have more of an impact on your goals as a writer. A simple example is a (good) poem. Once finished, it could: (1) be published in a journal on its own; (2) be part of a sequence that is published together as a chapbook; (3) be folded with this chapbook sequence into a collection as one of the book’s sections. Barring other factors, that poem might be worth committing to rather than a poem that you know will not be part of a sequence, etc.

The project you most fear. As noted above, I like to commit to projects that I don’t think I can do. There are problems inherent in this approach, but I cannot think of a better way to grow as a writer.

What have you already done? My curse for many years was that I worked on many projects at once. (My curse now is that I am still finishing those projects, and I have very little time for new projects.) My entire writing life changed when I instituted one simple little rule: I can only work on the book I am closest to finishing. I made this rule for myself in 2008. In 2009, I published my first book. I had a second book accepted before that one was published.

The last suggestion is the one that has worked the best for me. Since I started forcing myself to finish book-length projects in order of what is nearest to completion, I have averaged a published book each year. Before then, I struggled to finish anything for a decade.

Right now, I really want to work on a novel. But I am very close to finishing a book of short stories. And I “owe” a director a screenplay. So: the short stories first, the screenplay second, the novel third.

I try to imagine that I am two people: a writer and that writer’s jerk boss. The jerk boss hat goes on when I make decisions about what the writer is going to have to do, whether the writer wants to do that thing or not.

Prioritizing Projects

Now that you have committed to a list of projects, you still face the problem of which projects to prioritize (unless, of course, you are more ruthless than I, and your list is a short one that includes a single project).

I will provide an overview of the system I use to prioritize what I work on when. This is meant to be illustrative rather than prescriptive — your system might differ depending on your writing focuses and goals. You need a system, but not necessarily this system (although you could do worse).

I keep a revolving list of my Top 2 writing priorities. They break down this way:

A major project, like a book or screenplay

A minor project, like a single poem or a book review

“Major” and “minor” here just refer to length. As noted above, I try not to commit to any projects I don’t see as significant (“major” projects in their own right). Once in a while, of course, I am a hack for money (but only on “minor” projects).

I try to only work on the major project, and ignore the minor project. If I cannot ignore the minor project — for example, if the deadline for a book review is approaching — then I spend some time on the major project (a minimum of 15 minutes) before I allow myself to shift focus to the minor project.

Sometimes, if the major project is going terribly, I will just put in my time with it and then shift to a more fun minor project. So the major project proceeds faster or slower depending on how many more pressing deadlines I have, or how engaged I feel with the project that week.

Here’s what I’m doing these days:

Major Project — A screenplay called Edenbridge — this is a priority because I am working on it at the behest of a director, and because of a grant deadline by which I have to complete and submit a sample of writing and an outline.

Minor Project — This post you are reading, obviously. I have prioritized this blog post because I am teaching a creative writing class, and one of the students asked me to discuss this particular topic. This post is one of those “projects that live multiple lives,” in that it will serve as (1) class notes for a general discussion, (2) a more detailed look at the topic to aid that particular student, (3) some material for this website, (4) draft work towards future articles on the topic for freelance publication, and (5) draft work towards an eBook on working productively as a writer (an publishing experiment I want to try).

Finishing Projects

The important point, and the reason for this system, is that even if I have a lot of other things to do, and even if I am bored or feeling blocked, the major project gets worked on and gets finished.

Let me repeat that. Even if I have a lot of other things to do, and even if I am bored or feeling blocked, the major project gets worked on and gets finished.

Since I force myself to focus on things that are closest to being finished anyway, I make a fair bit of progress. Of course, this is possible only because of all the undirected, random progress I made on various projects in the past.

So, it is something of a false industry. The result is that I am viewed primarily as a poet, even though I write very little poetry, and mostly write fiction.

Nevertheless, how people view me and my writing is not my concern. My concern is writing.

How do you know when you are finished a project?

This is a question people ask a lot. I don’t have a good answer.

I decide that I am finished a project when I don’t know how to improve it any further, and it feels like no matter how much I work on it, the project is only changing superficially, not improving substantially.

This happened with The Politics of Knives. I worked on the book for many years. I felt like I was getting nowhere — not making the book better, just making it different. I didn’t know what to do. I solicited feedback from people, but the feedback all clashed. Nobody had a clear idea what was wrong with the book.

I didn’t know what to do with it. It was publishable, but not what I wanted it to be. I decided, in the end, to submit it to Coach House Books. I had such an amazing experience working with them on Clockfire, and they seemed well-disposed towards me. So I gambled. I suspected they wouldn’t want to publish the book as-is. But I also knew they would read the manuscript and consider it carefully, since they seemed to want to work with me again. My gamble was this: maybe Kevin Connolly would read it and realize what was wrong with it, and like it enough that we could fix it together.

That’s more or less what happened — Kevin suggested cutting out a section of the book where I had a series of single poems. The rest of the book consisted of poem sequences. I saw in a flash that the whole book should consist of sequences, and that I should rewrite each sequence to cross-connect with the others in oblique ways that might not be apparent to the reader.

Alana Wilcox also expressed concern that so much of the book had been previously published (there are odd rules concerning grants to publishers in Canada). She wondered if I had any newer work that I could include.

I realized then that I should pull out half of the book and replace it with new material. Alana was talking about something else, but she was right that the sections had been written too far apart and didn’t feel cohesive. Kevin seemed to get a little concerned at this point, because I started gutting and trashing sections that he considered strong, but then I replaced them with stronger stuff (aside from one proposed section that didn’t work, which he called out).

In the end, I “finished” the book and mailed it away … and then “finished” the book again en route to publication. My first book, Ex Machina, underwent almost no changes during the publishing process, by contrast.

Paul Valery once wrote that works of art are “never completed except by some accident such as weariness, satisfaction, the need to deliver, or death.” Sometimes you need to accept that you have come to the end of the idea and move on, even if you are not satisfied.

March 2, 2015

Praying for Permission from the God of Writing

A few weeks back, I wrote about How to Write a Lot by Writing on Schedule and that post almost immediately became the most popular thing ever written for this website. Recently, Elisabeth de Mariaffi (author of the most recent addition to my to-read list, The Devil You Know) mentioned that post on her website. In her article, de Mariaffi notes a sign on her office door that simply says “NO” to ward off interruptions. Inside, also pinned to the door, is a second sign, one “that tells the writer YES.”

I don’t have an office door, so I don’t have a sign (my headphones are my “NO”). But I do something similar to de Mariaffi’s “YES” — I pray to the God of Writing.

The God of Writing

The God of Writing is a beat-up index card with the words “The God of Writing” scrawled on it. I stamped some Canadian maple leaves on there too, on a lark.

What does the God of Writing do? Like any good God, it answers prayers. I pray, then I flip the card over for the answer to my prayer. Here’s how it works.

Dear God of Writing, I despair, for the kitchen is a mess. This office is a mess. My whole life is a mess. I should clean up these messes, but I would like to work on a poem about The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. God of Writing, would you please grant me permission to ignore this mess and write a sonnet about Leatherface instead?

Asking Permission

I created the God of Writing in response to my Catholic guilt. Although I identify as an atheist, it is more correct to say that I am a lapsed Catholic, since I was once confirmed in the Church and have not been excommunicated. More importantly, I suffer as much as any good Catholic from good ol’ Catholic guilt.

Those unfamiliar with Catholic guilt find the concept bizarre, so let me universalize it for you. The best parallel is the guilt that you feel when you are enjoying something. Not guilty because it is bad for you — not a guilty pleasure — but guilty whether or not it is good or bad for you. You feel guilty because of your enjoyment, and the thing you’re enjoying is irrelevant. So, when writing, I feel guilty for writing. I feel like there is something else I should be doing instead.

But there isn’t! Does this feeling go away just because you are a writer, and in fact your actual JOB is to write things? Nope. It gets worse, actually. In fact, if I don’t write then I feel guilty for not writing. Then when I start writing, I feel guilty for writing.

That’s right — Catholicism perfected guilt.

What’s the solution? My solution is the God of Writing. I literally go through an idiotic ritual requesting permission from God to write, even though I do not believe in God. The mockery of the ritual, which I built into the ritual itself, helps salvage my dignity.

I don’t pray to the God of Writing often, but I do when I need to. Just like I imagine de Mariaffi takes the signs seriously only on her bad days.

Giving Yourself Permission

Whether you post a sign on your door, or pray to the God of Writing, you need to give yourself permission to write. Sometimes, you need to give yourself permission to write badly, just to get the bad writing out of the way and relieve yourself of the anxiety that so often attends writing.

If you are a writer, and see writing as your career or your hoped-for career, the need to write should be obvious. Yet it is not always easy to write, because so often you will work on a project that has no definite deadline or even any definite future. You want to write a novel, but nobody has asked you to write a novel, nobody seems interested in your novel, there is no guarantee that anybody will want to publish your novel, or read your novel, and maybe when it’s done not even you will want to see the novel published or read. There is often no definite deadline associated with a large project like a novel, and definitely not any assurance of money or fame.

As difficult as it is in a circumstance like this, you need to give yourself permission to write. Nothing you do is as important as actually sitting down and writing, if you are a writer. (When it comes to working, at least. Probably a lot of other things in your life, non-work things, are far more important.)

This is an especially difficult thing to remember and keep focused on when you are successful as a writer. Success of any sort, major or minor, brings with it a lot of work. Work that isn’t writing. When you’re filling out forms and replying to emails, and drowning in writing-related work, it is difficult to remember that writing-related is NOT writing and therefore you need to force yourself to pull away from that thing that is almost due and focus on that thing that will NEVER be due.

The problem is compounded if you do not see writing as your career. I talk to a lot of people who write on the side, while focused on some other career, and I notice that they have the largest problem with this, because of course they see writing as a distraction from their career. They want to write, but they feel like they can’t spare the time, they can’t justify writing just because they enjoy it.

What I try to explain to them is that writing is the thing that will make their career. They want to be an accountant — well, every other accountant is an accountant. How can they set themselves apart? By being the accountant that writes. They can build an entire side business this way, or just build a reputation this way. Their writing has incredible potential to advance them in their non-writing career.

Even if their writing seems totally disconnected from their non-writing career, they would do well to connect the two. Maybe you’re an accountant that writes fantasy novels. Great! Start building a client list of fantasy novelists! Write a book called Write Off That Cool Sword: Accounting for Fantasy Novelists and hit the convention circuit. Write off your travel! You’ll be drowning in business.

Money, Writing, and Magic

I could (and might) write a whole book about money and writing, so I will just say a few quick things in summary. Money and writing connect over this issue of permission because so often we neglect writing because the time spent seems like a bad investment.

People say that it is impossible to make money writing. That’s not true. What’s true is this: It is very easy to make a little money writing. It’s very hard to make a lot of money writing. What is impossible is making a “regular” amount — making the same money, with the same regularity, that you would make working at McDonald’s.

But so what? Let’s put aside the important, idealistic reasons you might want to write. Let’s focus on the narrow band of practical, careerist reasons you might write — since these are the kinds of reasons you will find to not write.

Writing is not a great way to make money — it’s a great way to create opportunities. (Sometimes these lead to money in roundabout ways, sometimes not.) Being able to write is like having a magical power that makes everything in your life easier and provides you a shortcut to accomplishing anything. But you need to learn how to wield the power, which isn’t easy. And the power demands a price: time and blood. And if you underestimate your power, it will leave you.

You need to give yourself permission to not make money writing, and then write anyway, and trust in the God of Writing. Then pay attention, and thank the God of Writing when its blessings rain down.

February 25, 2015

The Surprising Reason I Write Such Long Blog Posts — and Why Maybe You Should Too

February 23, 2015

A few comments from Ryan Fitzpatrick on Why Poetry Sucks

Here is a snippet from Ryan Fitzpatrick (my co-editor), recorded for a talk I gave at the University of Winnipeg on Why Poetry Sucks: An Anthology of Humorous Experimental Poetry.

Ryan refers to a few things here:

Michael Lista’s negative review of Why Poetry Sucks in The National Post

Our fake review anticipating a review like Lista’s in The Winnipeg Review

The introduction to the anthology Why Poetry Sucks

Here are a handful of my own remarks from the talk. They are disjointed and undeveloped because I was extemporizing, and also reading poems and excerpts from the introduction, and of course playing the video, but they provide a bit more context. Of course, the anthology is where the beef is at, if you were wondering where’s the beef.

*

One of Ryan’s own poems (“Watch for Exploding Cells” from Fake Math) first brought me to the basic idea for this anthology. I had become annoyed with the constant complaints I would hear about experimental poetry — especially about poetry by women writers — and I started to feel that there was an oppressive quality to the complaints, a power dynamic beneath their expression.

The litany of complaints often boiled down to two basic assaults, which were that (1) the poets were just fooling around and not being serious enough, or (2) the poets were being too serious and had no sense of humour but were just straining to make political or theoretical points. I thought it funny that these contradictory attacks would often be made about the same poets, and that often the really nasty reviews of experimental work were made by people who clearly had no idea how to read the work (never mind notice when somebody was making a joke). In other words, they just didn’t get it, and so isolated its humour (or perceived lack of humour) as its weak point, the way to crush it.

At the end of Ryan’s poem, he writes:

A new weapon in the war against explosions:

EXPLOSIONS! Hearing aids may explode!

It is easy to read into the double meaning of the word “cells” as terrorist cells — and also, of course, as prison cells, which is something the poem itself clearly demands given an earlier line about “Brazil’s exploding prisons!” — and so this line seems clearly to resonate as a critique of the war on terror. Yet even a simple reading like this is often beyond critics of this kind of poem, and so the use of a comedic technique often gets used as a reason to dismiss such poems — but then when comedy is missing, the poems are dismissed as too “arch.”

*

One specific inclusion in Why Poetry Sucks is “Chapter U” from Christian Bök’s Eunoia, a prose poem in which Bok only uses the vowel U. Much of Eunoia, including a line from this chapter, was dismissed by Carmine Starnino, and here is the most puzzling of his complaints: “These sentences — tonally trapped between Dr. Seuss and the Jabberwocky — come off a little silly” (A Lover’s Quarrel 130).

To me that is a stunning complaint, if only for negative comparisons to Dr. Seuss or Lewis Carroll. Yet elsewhere, Starnino complains that “humourlessness is the most galling failure of our current crop of experimental phonems” (Lazy Bastardism 165).

*

When this book came out, Michael Lista gave it a negative review in the National Post — a review that, funnily enough, we had anticipated and parodied before it existed — we filed our own negative review of the book (called “Why Why Poetry Sucks Sucks”) with The Winnipeg Review before Lista had published his.

I appreciate Lista taking the book seriously (I’m serious!) and reviewing it, and felt that his review was everything I wanted it to be, in a way. (Although I like Lista’s poetry, I find his reviews too conservative.)

He complains that the poems aren’t funny enough, even though our introduction makes it clear that we don’t really care how funny the poems are — we care about how a comedic technique is being utilized in the poems for an experimental purpose, usually a political purpose, and therefore claim that there is something very serious about the jokes of these poets but also something very funny about the moments when they are being serious. Lista fails to see, or just doesn’t care, that our focus is on how both experimental poetry and comedy use similar techniques to unveil power relations.

*

So why does poetry suck? What interests me most, in poetry or fiction, are texts that demand reader participation but then structure or reflect on that participation as a traumatic or terrible thing. So what most interests me in poetry are what Gregory Betts calls “post-avant” poets, who often use poetry to advance social critiques of power relations, but at the same time self-critique the value of offering these social critiques in poetry.

The world sucks because of power, but poetry sucks for not being powerful.

February 16, 2015

What Writers Can Learn from Letterman’s Top 10 Lists

The more I write, and analyze writing, the more important escalation seems. While an elemental aspect of narrative, escalation also appears significant in poetry, even (perhaps especially) in experimental work that (on its surface) appears to have no clear structure. Often, these works are structured, in that they escalate.

Let’s look at one of my favourite gags, the September 22, 1989 Top 10 list from Late Night with David Letterman. This show, which pre-dated Late Show with David Letterman, was well-known for its oddity. One night, Letterman rotated the camera 360 degrees over the course of the hour, so that for part of the show everything was upside-down. There was even an episode in which Letterman was too tired to really do a show.

The Top 10 list of September 22, 1989 was “Top 10 Numbers Between One and Ten”:

Seven

Four

Ten

Three

Eight and a half

Nine

Two

One

Eight

Five & Six (tie)

Let’s examine the writing choices here, and see how the joke operates through escalation, by setting up and then smashing expectations. You have to keep in mind that Letterman would be reading these out loud, one at a time, so that the audience would receive them very slowly compared to how quickly you just read down that list.

As soon as Letterman says “Number 10: Seven,” the audience knows that the numbers will be listed out of order. It seems like the regular escalation, from 1 to 10, is being thrown away in favour of randomness. On one level, this is true. There’s no reason that we begin with 7 rather than 3. On closer inspection, however, Letterman’s writers have made two careful choices that re-introduce some structure, and allow for escalation.

With “Number 6: Eight and a half,” Letterman throws a wrench into the entire joke. This operates almost like a plot twist might. The audience thought this was a silly, simple disordering of the numbers, according to no apparent logic. Now, however, we can see that Letterman is not just disordering the numbers, but playing around within the set. We are not just dealing with whole numbers. Now it is clear that he could throw in another fraction, or a decimal, or something along those lines.

Note that he does not. Why not? Why can’t Letterman say something like “Number 2: Five and Four-Tenths”?

Because there wouldn’t be any escalation. It would be the same joke, repeated. Once Letterman introduces “Eight and a half,” he makes it clear that the joke is not that the numbers from 1 to 10 are being ranked out of their “natural” order. This is the joke premise, but it is not the joke. The “jokes” happen when Letterman departs from ranking whole numbers randomly, and introduces some apparent order.

Note what he says instead for “Number 2.” First, note the position. This is the penultimate ranking. It’s the obvious place for another twist. We expect some crazy number, since we previously were given “Eight and a half.” What do we get? “Eight.”

Both “Eight” and “Eight and a half” are on the list.

What does this matter? It matters because it means — and if we are paying attention, we understand that it means — that not all of the numbers made the list. “Eight” is sort-of taking up two positions. So, one of the numbers must be left out. But which number?

Notice how this simple listing of numbers has managed to achieve something like a narrative drive. It begins in apparent randomness, with a catalytic moment of sorts: when the numbers begin ranking out of their natural order (the state of the world has been disturbed, like it typically is at the beginning of a story). Then there is something like a “plot twist” when Letterman reads “Eight and a half” — you might consider something like a conflict to be arising here, where we begin to wonder if he’s really going to read out all the numbers after all.

Then, we reach something like a crisis moment — he reads out “Eight” and we now have to deal with the suspense of whether or not the list will be completed. How could it be completed? This is the formulaic structure of a Hollywood movie. Here is the point in the film where it seems like the hero’s goal can never be accomplished. Letterman only has one slot left, for two numbers.

The solution is obvious in retrospect, but elegant in execution: a tie between Five and Six. Notice how this move resolves the apparent conflict that began arising with “Eight and a half” and seemed unresolvable with “Eight.” You almost breathe a sigh of relief as you laugh out loud.

The Structure Below the Surface

Hiding this sort of narrative structure beneath text that appears, on its surface, to lack structure, is one of the most useful writing techniques I have come across. This is how David Lynch works. He puts together events that appear to make very little sense. However, they always feel like they make sense, because he slavishly follows narrative structure. Scenes begin, escalate, and end. They may do so in absurd ways, and not seem to accord to any sort of narrative logic, but they always feel like they are proceeding logically.

Or listen to the song “Jizz in My Pants” by The Lonely Island — notice how the song escalates. It takes less and less, smaller and simpler things, to make him jizz in his pants. Eventually, he jizzes before he even has a chance to tell you what caused him to do so.

What unites narrative and poetic logic is this very sense of escalation, of producing and developing conflicts — however small, silly, or strange.

February 8, 2015

Write a Lot by Writing on Schedule

When I meet writers, whether emerging or established, I ask them the same ice-breaking question: What do they find to be the hardest thing about being a writer?

The most common answer is finding time to write.

I’m not surprised, because finding time to write is impossible. What surprises me is that writers even bother trying to find time to write.

The answer suggests that writers don’t understand time, and don’t understand the basics of self-management. They may know how to write, but they don’t know how to work. They overlook or discount basic strategies — even though they might use these same strategies, with exceptional results, in other areas of their lives.

“Finding” Time to Write

There is one way to “find” time to write: Look at a calendar, and decide what day you will write, and what time. In other words, you cannot find time, and time will not magically appear. You can only allocate your time, in advance.

Similarly, there is one way to be a productive writer: Write according to a schedule.

The Importance of Your Schedule

Writers that resist scheduling writing time have many excuses. In his excellent book How to Write a Lot, psychologist Paul J. Silvia labels these excuses “specious barriers.” He identifies and refutes the most common of these specious barriers to writing, the first being trying to find time to write:

Why is this barrier specious? The key lies in the word find. When people endorse this specious barrier, I imagine them roaming through their schedules like naturalists in search of Time To Write, that most elusive and secretive of creatures. Do you need to “find time to teach”? Of course not — you have a teaching schedule, and you never miss it. […] Finding time is a destructive way of thinking about writing. Never say this again. (12)

Silvia’s book is aimed at academic writers (which is why he assumes that his readers are also teachers), but everything in the first half of the book applies equally to creative writers (who are often also teachers). Even if you aren’t a teacher, you routinely schedule things that aren’t writing, and you stick to your schedule — unless you simply have no control over your life (in which case, writing is the least of your problems).

A barrier that Silvia doesn’t address fully, but which people often bring up when talking to me, is the anxiety that attends the act of writing. Many writers I know (myself included — I’ve been there) feel guilty about not writing but also anxious about writing. The less they write, the more guilty and anxious they feel. When they do write, finally, they often do so in binges (usually before a deadline), and the experience is horrible due to the pressure of the deadline.

Yet they succeed (sometimes), turning in their writing by the deadline. Perhaps they aren’t proud of the work produced under this pressure, and negatively reinforce their own anxieties about writing. Perhaps they are proud of this work — thus positively reinforcing their bad habits. Either way, these writers reinforce their assumptions about themselves and their writing: (1) they work best when they binge-write, (2) they aren’t capable of keeping a schedule, (3) their anxiety about writing is uncontrollable or perhaps even necessary to their art.

All of which is nonsense. Silvia — a psychologist, remember — addresses the issue adequately in a little over a page:

Binge writers spend more time feeling guilty and anxious about not writing than schedule followers spend writing. When you follow a schedule, you no longer worry about not writing, complain about not finding time to write, or indulge in fantasies about how much you’ll write over the summer. Instead, you write during your allotted times and then forget about it. We have better things to worry about than writing. […]

When confronted with their fruitless ways, binge writers often proffer a self-defeating dispositional attribution: “I’m just not the kind of person who’s good at making a schedule and sticking to it.” This is nonsense, of course. People like dispositional explanations when they don’t want to change (Jellison, 1993). People who claim that they’re “not the scheduling kind of person” are masterly schedulers at other times: They always teach at the same time, go to bed at the same time, watch their favorite TV shows at the same time, and so on. I’ve met people who jogged at the same daily time, regardless of snow or rain, but claimed that they didn’t have the willpower to stick to a daily writing schedule. Don’t quit before you start — making a schedule is the secret to productive writing. If you don’t plan to make a schedule, gently close this book, clean it so it looks brand new, and give it as a gift to a friend who wants to be a better writer. (14-15)

Sometimes, writers resist making a schedule because they don’t have ideas for writing — this is perhaps the most specious barrier of all, since ideas for writing can simply be stolen (à la Shakespeare or Kenneth Goldsmith) or manufactured by force (as any writing exercise will prove). Nevertheless, some writers persist in the mistaken belief that they must wait for inspiration, even though:

Waiting for Inspiration Doesn’t Work

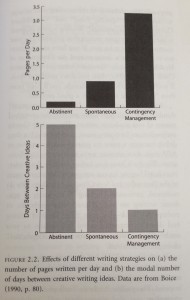

Most good writers already know this. However, many still cling to the fallacy that inspiration is necessary to produce any writing, or to produce good writing. Silvia points to research by R. Boice, who “gathered a sample of college professors who struggled with writing, and […] randomly assigned them to use different writing strategies” (24).

Although “college professors” is a very narrow, limited sample, the results are intriguing and instructive for writers of all stripes. The three writing strategies assigned by Boice were:

abstinence — writers told not to write at all, “forbidden from all nonemergency writing”

spontaneous — writers who scheduled 50 writing sessions but did not have to keep them — they could write anytime, and also only had to write during these sessions when they felt inspired — in other words, they could write as much as they wanted, whenever inspiration struck

contingency management — writers who scheduled 50 writing sessions, were forced to write during each session, and were told not to write outside of these sessions

The results? See for yourself:

The contingency management writers wrote 3.5 as much as the spontaneous writers, and 16 times more than the abstinent writers. Most significantly, writers “who wrote ‘when they felt like it’ were barely more productive than people told not to write at all” (24). In addition, “forcing people to write enhanced their creative ideas for writing” (24):

The typical number of days between creative ideas was merely 1 day for people who were forced to write: it was 2 days for people in the spontaneous condition and 5 days for people in the abstinence condition. Writing breeds good ideas for writing. (24)

I must acknowledge that Silvia does not suggest, anywhere, that the anxiety some associate with writing will lessen during the writing process. Common sense dictates that the more familiar and practiced you become, the less you will feel like an imposter or filled with anxiety, but many writers never let go of these feelings. Writing, in my experience, remains difficult and seems sometimes to be getting more difficult.

Nevertheless, this is irrelevant. The difficulty of writing will of course decrease with practice, but creative writers (ideally) are always working to raise their skills and so taking on tasks of increased difficulty, which from time to time will negate the benefits of practice. The end result? Either writing gets easier, and your skills barely improve, or writing gets harder, but your skills improve substantially.

Regardless, the best way to be productive (with difficulty or without) and to get control of your anxiety about writing is to demystify the process and normalize the activity through repeated exposure.

“The Schedule’s the Thing,” Like Shakespeare Should Have Said

Both Paul J. Silvia and David A. Rasch (another psychologist, this one a specialist on writers who struggle with blocks, procrastination, and related issues) agree that the details of your writing schedule (e.g., when you write, how long you write) are somewhat irrelevant in a general sense. If you have specific goals that require specific time commitments, then it might be a different matter, but generally speaking the important thing for writers is to institute a writing schedule, no matter what that schedule might be.

Silvia puts it this way:

The secret is the regularity, not the number of days or the number of hours. It doesn’t matter if you pick 1 day a week or all 5 weekdays — just find a set of regular times, write them in your weekly planner, and write during those times. To begin, allot a mere 4 hours per week. After you see the astronomical increase in your writing output, you can always add more hours. (13)

Rasch, in The Blocked Writer’s Book of the Dead, takes a more detailed look at the psychological barriers (specious and otherwise) that writers put up to avoid writing. The Blocked Writer’s Book of the Dead is structured like a workbook, and is of more use to writers with severe procrastination issues or other mental blocks that may prevent them from writing. (Ignore its cheesy cover.)

Rasch is less of a tough-love advocate than Silvia, but he still takes a behavioural approach and agrees fundamentally about how to be a productive writer. Here are a few of the things Rasch has to say about writing schedules and related matters:

Many writers with productivity problems have trouble with time. … Every day, through conscious planning or by unconscious default, you prioritize your activities and make decisions about how to spend time. It can be quite a challenge to determine how much time the writing portion of your life requires, and to incorporate that into a workable routine. (18)

I have worked with several writers whose primary challenge was taking the step of sitting down at their desk. Their anticipatory anxiety or other resistances create a mental barrier against taking the first step. Often they are entertaining an inaccurate and exaggerated estimate of the agony that will ensure if they write. (19)

I encourage blocked writers to make failure less likely to occur. For many reasons writing is frequently difficult to do, so respect that reality […] Make changes by taking small steps that would be difficult to not do. For instance, if your goal is to start writing every day, if you make the sessions short (15 minutes) you may find it hard to rationalize skipping the session. I encourage you to be pragmatic and do what works, whether or not it fits your image of what a “real” writer would do. (62)

An advantage of a regular schedule is that it eliminates the daily process of deciding when to write. Each time you have to make a decision about writing, it increases the likelihood that you will decide not to do it. The more regularly you write, the less dreadful it feels to face it each day. To the extent that you generate new, positive associations with writing through regular practice, you reinforce your efforts. (63)

Scheduling writing is not the only way to become more productive, but I have seen it produce powerful results for those blocked writers who found a way to move in this direction. Write daily. Write daily. Write daily. This is the single most important piece of advice in this book. (63)

Here is a nutshell summary of Rasch’s other advice regarding how to make a work schedule (I have simply recorded the subsection headings under “Make a Work Schedule”):

Write daily

If work avoidance is a problem, begin with short writing periods

Choose a time when your energy is good and distractions will be minimal

Resist the urge to overdo it

Track your performance

Rasch’s book is worth a read (he even deals with a problem on the other end of the spectrum, writers who write a lot and work long hours, who write often and without much anxiety, yet have little to show for it). He briefly addresses a host of issues, including dealing with criticism, actual psychological disorders like depression and how they might relate to writing, and so forth. Rasch provides a variety of strategies writers can use to be more productive and reduce their anxiety, and also helps the reader identify their actual issues with writing and get a sense of whether or not they might need to be addressed somehow beyond the book.

One simple piece of advice that Rasch offers, which I have found especially useful, is to make a “routine, simple pleasure contingent upon writing first.” I don’t drink coffee except when I write (sometimes I allow myself a coffee after I write; for example, if I want to go to coffee with somebody, then I write first). I appreciate coffee more, and I don’t over-caffeinate, and I write.

My Writing Schedule

I have to keep shifting my writing schedule each term, which is frankly a bad idea. But that’s my reality. I’m no saint, and I will often fail to follow the schedule as rigorously as I should. But I produce a lot of writing and I’ve published five books in the last five years, so I can attest to the fact that even a half-followed schedule will work wonders for you. Here’s mine in a nutshell:

I write weekdays, not weekends. I take two weeks off every year. (I track the days I take off.) This is, of course, my ideal and not my reality.

This term, I am writing from 10 – 11 a.m. every weekday. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, this is pretty much all the writing I can do — nestled right between my morning classes. On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, I will keep this same start time but then keep writing as long as I can. As of this very minute, it’s a Wednesday, and it’s 12:44 p.m. Right this minute, I’ve written 2270 words today, since 10 a.m.

I set an alarm for 9:55 (my iPhone plays Elvis Costello’s song “Every Day I Write the Book”). When it goes off, I make coffee, then I start listening to Agalloch, then I start writing.

Your Writing Schedule, and Defending It

What is your writing schedule? Have you had success with a schedule, now or in the past? Have you had problems sticking to a schedule? Let me know.

If you haven’t yet done so, start a schedule. Try it for a week — just 15 minutes each day, as Rasch suggests. See how it goes. You’ll be surprised.

One problem you’ll run up against is people not respecting your schedule. That’s okay. Only you need to respect it. Jealously defend and guard your time. As Silvia puts it, when you start saying “no” to requests that conflict with your writing schedule, you will meet with resistance from others.

That’s life. Refuse anyway. As Silvia puts it, “only bad writers will hold your refusal against you” (16).

February 4, 2015

Natalee Caple on Writing Titles

I had the pleasure of interviewing Natalee Caple about writing titles. Since I met Caple, she has completed a poetry book, The Semiconducting Dictionary (Our Strindberg), a collection of short fiction, How I Came to Haunt My Parents, and a novel, In Calamity’s Wake. I don’t know how she does it, while working and raising a family.

Oh, wait, I do know! She is one of the hardest-working writers around, and one of the most dedicated. Her students at Brock University are some of the luckiest.

Natalee Caple is the author of seven books of poetry and fiction and the co-author of several incarnations of a full-length play titled i-Robot Theatre (based on Jason Christie’s i-Robot Poetry) with the Swallow-a-Bicycle Theatre Collective. Her most recent novel, In Calamity’s Wake was published to international acclaim in Canada and the US in 2013. Her collection of poetry, A More Tender Ocean, was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. Her book of short stories, The Heart is its Own Reason, was called “moving … arresting” by The New York Times. Her novel, Mackerel Sky was called “ breathlessly good” by the Washington Post. Natalee’s work has been optioned for film, and nominated for a National Magazine Award, the Journey Prize, the Bronwen Wallace Award, and the Eden Mills Fiction Award.

January 20, 2015

4 Simple Editing Tricks That Are All The Same Trick

Editing is a complex process, which requires analytical rigour and solutions specific to the text in need of editing. At the same time, there are some fundamental rules of editing that can be applied without much trouble for immediate improvement.

(This sourdough crab wants to help you be a better writer!)

These are simple prescriptions. They are one-size-fits-all. With complex texts, especially unconventional pieces of writing, they will fail you. However, most students or beginners should simply apply these rules without questioning them. They will move your work forward by leaps and bounds, and move you closer to the moment when you will require more complex solutions, and have developed the skill to dispense with prescriptions like these.

1. Be Specific

I learned two things in my Christian grade school. I learned that if you hit a student’s fingers with a ruler when they make typing mistakes, they will learn to type slowly but accurately. I also learned the most important thing I ever learned about writing.

My teacher used to hand back my papers with the letters “B.S.” scrawled on them. I assumed this meant my writing was bullshit. He was a tough, gruff teacher. At the same time, I couldn’t believe my Christian school teacher was actually writing “bullshit” on my papers. Finally, I summoned the nerve to ask him what “B.S.” meant.

“It means Be Specific,” he said. I sighed, relieved. “Why, what did you think it meant?”

Well, he asked. “I thought it meant my writing was bullshit.”

“Sure,” he agreed. “If you aren’t being specific, you’re just writing bullshit.”

What does this mean in practice? First off, it means to avoid words with unclear referents. In other words, take words like he, she, it, they, this, and so on, and replace them with specific words.

If I was writing about Romeo and Juliet, I might end up with a sentence like this:

In the play, the author shows how their sacrifice is misguided.

A revision would be more specific:

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare shows how Romeo and Juliet’s sacrifices are misguided.

My next revision would isolate words and phrases that are not specific enough. In this case, the first question is What sacrifices?

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare shows how when Romeo and Juliet sacrifice themselves by committing suicide, they are misguided.

Here is when I finally get to the problem with the sentence. It was hidden earlier, because my language was too vague. This is the problem with not being specific. Not only does the writing lack clarity, it hides its problems. The real issue here is this: How are the sacrifices misguided?

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare shows how when Romeo and Juliet sacrifice themselves by committing suicide, this youthful rashness is meant to bring them together (in death) but actually prevents them from being together (since Juliet would have awoken and been reunited with Romeo if he hadn’t killed himself).

My revisions should get more and more specific in each draft. Not only will my drafts become more clear, and my arguments more complex, but the additional detail will lengthen the paper.

When students run out of things to write, and start panicking and repeating themselves and rambling to fill up space, their efforts are misguided — just like Romeo’s! They are committing academic suicide.

They should just revise each sentence to include more detail. That way, they will fill up the space by developing their arguments, and clarify them while adding complexity, rather than just vomiting onto the page.

2. Eliminate the Passive Voice

Passive voice constructions use some form of the verb “to be” in order to construct a sentence where the subject of the sentence is acted upon by some agent, rather than being the actor itself. Here are two examples of a sentence written in the passive voice:

The road was crossed.

The road was crossed by the chicken.

Active voice constructions turn the subject of the sentence into the actor. Here is an active voice revision of the above sentences:

The chicken crossed the road.

The problem? The chicken is what this sentence is about. The chicken is the one that did something. So the sentence should be about the chicken. Not the road.

On a structural level, the issue is that the actual thing the sentence is supposed to be about (the chicken) is put at the end of the sentence in the passive voice example.

Or — and this is worse — you write the sentence without ever mentioning the chicken.

When a sentence gets really long, this kind of passive voice sentence gets unreadable:

The road was crossed on Thursday at five o’clock when the sun was just starting to set in the wintertime and shadows were lengthening across the road sign that was yellow and fading and could barely be read anymore.

I don’t know what the hell is going on here. Certainly, I don’t know that the point is that a chicken is what crossed the road.

When you do a revision, first go through your paper and circle every occurrence of a “to be” verb — every “is” or “was.” Often, these will be close to another verb, like “crossed.” Rewrite the sentence to eliminate the “to be” verb and just use the verb close by, which is the verb you want to use in the first place.

There will be a few instances where you may retain the verb “to be.” Basically, you want to only keep “to be” if you cannot rewrite the sentence and have the same point. In other words, if the point of the sentence is that something exists, you keep “to be.” If the point is anything else then you need to rewrite the sentence to put it in the active voice.

Figure out the subject of the sentence. Put that thing first (“The chicken”). Then find the right verb. Put it next (“The chicken crossed”). Then conclude the sentence.

3. Eliminate Adverbs and Replace Verbs

Adverbs are words that modify verbs. Often, they end in “ly” and are near a verb:

I ran quickly down the street to get some exercise.

I walked quickly down the street to get some exercise.

The presence of adverbs indicates one of two problems: (1) redundancy or (2) imprecision.

In the first example, I could eliminate the word quickly. Why? Because running is quick. The adverb does not help clarify my meaning.

The second problem is the real problem. I wrote “walked quickly” when I meant something else. I could have written “ran” or “speedwalked” or “jogged” or some other thing that I meant.

What adverbs often indicate is a writing error. I meant ran but I wrote walked. So I had to add the word quickly to cover up my mistake. I need you, the reader, to understand that I am not talking about walking. I’m talking about running or speedwalking or jogging — something quick.

The biggest problem related to this issue is when people write dialogue in fiction, then add an adjective to the attribution tag:

“Whatever!” she screamed furiously.

The problem here is that I wrote some lousy dialogue. “Whatever” does not convey the emotion of fury. It is not something people scream. So I tried to cover up my bad dialogue by telling you how to read it.

If I just wrote some better dialogue, I wouldn’t even need to have a dialogue attribution tag at all:

“I will MURDER you and your CHILDREN and your CHILDREN’S CHILDREN and your fucking DOG.”

I don’t even need the exclamation mark now.

The solution here is simple: go through your draft and circle every word that ends in “ly” Then ask yourself: Can I just delete the word? If so, delete it. If you can’t, then ask yourself the second question: What mistake did I make, that I am trying to cover up? Fix that mistake.

When can you use adverbs? What are they for? Adverbs work when they modify a verb in an unusual manner, to suggest an action that a single verb cannot convey. Here is the classic example from the King James Bible:

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face (1 Corinthians 13:12)

Darkly modifies see — see suggests clarity, but there is no clarity in life. Only in the afterlife, when we see things as they are, will true seeing be possible. Therefore, when we speak of seeing in this mortal coil, we mean sort of dark-seeing, like squinting through a dirty piece of glass, one that distorts things so that they are almost unrecognizable.

Instead of writing all that, I can use the poetic image of “see through a glass, darkly” — this is when adverbs are your friends. Otherwise, they are not your friends. They are enemies and you should murder them, and their children, and their children’s children, and their dog.

4. Eliminate Adjectives and Replace Nouns

You might have noticed that tips #2 and #3 were just variations of #1. You are killing non-specific verbs and replacing them with more specific verbs, and killing off some adverbs as you go.

The same is true with nouns. Why write dog when you mean terrier? Why write small dog when you mean teacup poodle? Whether you are writing an essay or writing a poem, teacup poodle clarifies and communicates your meaning more than small dog ever could.

Adjectives — words that modify nouns — will often tip you off (like adverbs do) to when you have used an imprecise noun. Again, go through your draft and circle every adjective — all the words that tell you how to read other words. Can you say something more specific, instead of whatever you just said in that sentence?

The simplest way to improve your writing is to look for the words that indicate weaknesses in your draft. Circle them. Revise the draft to get rid of them. Then go through your draft again. Circle the same kinds of words. Keep going. Keep going until you run out of time, patience, or talent.

Be specific, or you will just write bullshit. If you learn only this lesson, you will be a better writer than most people.

January 12, 2015

The Birds Finally Got On Twitter

The birds finally got on Twitter.

Their social media strategy: nest a while,

retweet #birdsong, spy on competitors.

Their target demographic loves Hitchcock

but is sick of references to Hitchcock.

“If you want real effectiveness,

check out this video courseware

and give us some birdseed, birdbrain.

Ensure your personal branding

is consistent across all platforms.”

Tweet Tweet. Expand. Collapse.

Reply. Retweet. Retweeted.

Tweet Tweet. Expand. Collapse.

Delete. Favorited. More.

January 7, 2015

A Musical Sacrifice of Metal to the Glory of the Writing Gods

When I write, I listen to music. Specifically, I listen to the metal band Agalloch. I do not listen to any other music by any other band. Ever.

I have a playlist in iTunes called “Writing” that contains every album by Agalloch. My iPad and iPhone also contain the same albums, so that if I am writing on them I can listen to the same playlist.

(Does this meet the minimum standards of a “playlist”? The albums are just ordered alphabetically by title and the songs have not been curated — except, I suppose, by the band Agalloch.)

Why music, why metal, and why Agalloch?

Music is theorized to aid creative brain function and focus, when it does not require conscious attention and thus does not become a distraction.

Even if those theories are nonsense, I find that metal works well to erect a “wall of sound” and drown out intermittent noises. When I write in public, or even at home when I am not alone, wearing earphones also dissuades people from interrupting me.

Metal also shares many qualities with classical music in terms of its song structures, so (according to my own unproven theory) I achieve some of the supposed intellectual benefits (it’s debatable) of listening to classical music (which I don’t really enjoy) while erecting this wall of sound.

The singer of Agalloch scream-grunts for the most part, so I have no idea what he is saying and I cannot sing along or become distracted by the vocals. I have listened to the same few albums by Agalloch almost every single day for years and I have no idea what any of the songs are about, although I catch a word here and there.

When Agalloch releases a new album, I buy it and add it to my playlist, but otherwise the playlist never changes and I never listen to any other music when I write.

Being Extreme

Does this seem extreme? It is extreme. It requires no effort or thought. All the effort and thought goes into the writing.

I always start with the same song — “Limbs” — because the album it appears on happens to start with an “A” (as does Agalloch!) and so one time when I dumped all my “metal” into a giant playlist this band and song were automatically loaded at the start. By happy accident, the song begins with a high-pitched, whining drone-melody that lasts about 35 seconds.

Then the other instruments crash in and begin a slow churn. This signals my reptilian writing brain the way Pavlov would signal to his dogs that the bell meant supper.

This is my behavioural science approach to writing — and it works. When I hear Agalloch, I start writing. I don’t find myself stuck, wondering what to write. My body just begins, because I have trained it to begin when the music begins.

My Life Without Agalloch

Can I write without Agalloch? Of course. I am less focused, and more distractible. I always was, anyway: the music was a solution to this problem, so without the music I revert back to the problem. I’m no worse off if for some reason I need or want to write in a space without Agalloch.

Can I write with other music? Of course. However, since I’ve trained myself to work with Agalloch, different music becomes a distraction. I used to make playlists for each project. What a waste of time. At best, I would procrastinate. At worst, I created great playlists that distracted me to the point where I stopped writing and just started listening to music.

Do you need to write with music, or with Agalloch? Obviously not. What I recommend is nothing so narrow — the point is to create a series of simple triggers, behavioural triggers, that you can use to let your body and mind know that writing begins now.

I use three such triggers (it’s best, with this approach, to keep things simple and the elements limited):

An alarm on my iPhone — it plays Elvis Costello’s “Every Day I Write the Book” five minutes before my scheduled writing time, to let me know that I should get ready

Coffee, which I only drink while writing, or after writing (I start making coffee when Elvis tells me to)

Agalloch (when I’m getting down to business)

The Final Flaw

The one drawback of the system is that I can no longer enjoy Agalloch. I’ve trained my body and mind to tune their music out.

Whenever I put on Agalloch’s music “just to listen to,” I start tuning it out automatically and begin to write. I can’t help it. I just start getting ideas for things to write, and since I always have a writing venue handy (like my phone), it’s easy to start.

I have sacrificed Agalloch on the desk-altar of the writing gods.

Credit where credit is due

The above-mentioned song, “Limbs,” appears on one of my favourite Agalloch albums, Ashes Against the Grain. All hail Natalie Zed for introducing me to Agalloch!