Rick Falkvinge's Blog, page 32

December 20, 2012

As UK Pirate Party Takes Down Pirate Bay Proxy, Two Other Pirate Parties Bring New Ones Up

Infopolicy: The sad defeat of yesterday was that the UK Pirate Party had succumbed to legal threats and taken down its long-used proxy for The Pirate Bay, after the copyright industry shamefully had threatened to ruin the Pirate Party’s executive personally. As a result, the Luxemburgish and Argentinian Pirate Parties have both decided to put up their own proxies in solidarity and action.

The copyright industry in the UK decided to go after the UK Pirate Party members personally over the organization’s proxy to The Pirate Bay, threatening financial ruin for them and their families in a lawsuit. This is unprecedented, unethical, and cancerous to society – in essence, a special interest putting its financial resources behind trying to destroy a political party as such because they disagree with the political direction. As a result, the PPUK decided to close the proxy and come back to fight another day. This is despicably shameful behavior on part of the copyright industry, and nothing short of corporate bullying of the “might makes right” type.

As a result of the shameful bullying from the copyright industry in the UK, we now see more proxies bloom across the world, refusing to let sharing, culture, and knowledge go silenced by corporate bullies. The Pirate Parties strike back by refusing to be silenced.

The Argentinian Pirate Party has a new proxy up to The Pirate Bay as of today at tpb.partidopirata.com.ar.

The Luxemburg Pirate Party has a new proxy up to The Pirate Bay as of today at tpb.piraten.lu.

“The Pirate Bay is only a search engine, like Google”, says Sven Clement, president of the Pirate Party in Luxemburg. “Due to the pressure from lobbyists, politicians all over Europe are seduced to expand the censorship infrastructure to prevent freedom of expression, the right to information and the free exchange of culture. With our proxy, we help circumventing the internet censorship of European countries!”

The Argentinian Pirate Party writes, “We wish the UK Pirate Party best of luck in their continued fight for free access to culture and knowledge, and have put up our own proxy to The Pirate Bay which you can access from anywhere in the world – including from the UK and other places where it has been censored.”

In particular, the Luxemburgish proxy can be expected to remain just as online as The Pirate Bay itself. The LU cabinet has been adamant that it’s not buying into the propaganda of the special interests in the copyright industry, and Minister of Economy Schneider has gone on record saying that “In Luxembourg, even illegal downloads are legal”.

In the meantime, the Swedish Pirate Party remains the Internet Service Provider of The Pirate Bay. We stand united against censorship and special interests.

(As a final note, if I were the copyright industry in the UK, I’d be a lot more careful in crossing that particular line – going after people personally, as well as their families – against an organization with representatives who are legally immune to any and all prosecution through their election mandate. If the copyright industry wants to play legal hardball, crossing that exact line against such an organization could well have been one of the worst decisions made in the history of humankind. But that’s just me being logical; the copyright industry isn’t exactly known for applying logic to their decision-making process. In this case, maybe they just got lucky that we’re quite nice and peaceful chaps at the end of the day.)

December 19, 2012

There Is Never A Need To Justify Sharing Culture And Knowledge

Copyright Monopoly: Just as some misguided people react with hostility to the fact that the copyright monopoly is not a birthright, they can react with hostility and demand a response to how sharing is “justified”. This, too, is misguided.

One example could be seen in the Reddit thread about The Pirate Bay being the world’s most efficient public library. For a while, the top comment was “whatever helps you justify it” (as in, the sharing of culture). This is a misguided expression based on the false premise that sharing knowledge and culture needs to be justified.

It is completely the other way around.

Humankind and civilization has advanced due to and because of people sharing knowledge and culture, and has never advanced when it has been locked up and contained. Sharing knowledge, information, and culture is also a good deed on an individual-to-individual basis. Whenever the ability to share and partake in knowledge and culture has been prevented, such as the burning of the library at Alexandria, it has always been regarded as a disaster for humanity in the history books.

And yet, some people believe that sharing – whether over The Pirate Bay, direct handover, or whatever other mechanism – needs to be justified.

It is true that the copyright monopoly has come at odds with the natural behavior of sharing and the right to share. But to enforce this monopoly, much more vital ideas in society – such as the postal secret – must be sacrificed, not to mention our cultural heritage. That is neither just nor reasonable, so that is what needs justification. It’s not just the copyright monopoly law itself that needs to be justified, but also individual compliance with the unjust monopoly law, on a case-by-case basis.

When somebody angrily asks you how you can share this and that knowledge “without permission”, state it as it is, that they are misguided, and ask how they could possibly justify requiring permission to share knowledge and culture. That goes counter to all of humanity’s history. Also, make sure to make a point that sharing never requires any kind of justification. (The current copyright monopoly laws are not enough of a justification, obviously, as they are unjust and completely out of touch with people’s actual and natural behavior.)

Sharing knowledge and culture is the natural state.

Therefore, any restrictions on sharing require very careful and strict justification.

December 17, 2012

Pirate Party Presses Charges Against Banks For WikiLeaks Blockade

Corruption: Today, the Swedish Pirate Party filed formal charges against Swedish banks for their discrimination against WikiLeaks, which has been systematically denied donations by payment providers since 2010.

Numerous payment service providers, including Visa, MasterCard, and PayPal, have blocked donations to WikiLeaks and other legal operations since 2010. Banks have been a part of the network of these service providers, which means that the banks actively participate in stopping donations without legitimate grounds. The Swedish Pirate Party says that this behavior is unacceptable and cause for grave concern, and has filed charges against the Swedish banks in question to try this behavior in court.

The charges were filed eariler today with the Swedish Finansinspektionen, the authority which oversees bank licenses and abuse of position. This follows an earlier initiative from the Pirate Party to regulate credit card companies on the European level in order to deny them the ability to determine who gets to trade and who doesn’t.

“The blockade is a serious threat against the freedoms of opinion and expression”, says the Pirate Party’s Erik Lönroth, who has been preparing the formal charges. “It must not be up to the individual payment provider to determine which organizations are eligible for donations. At the same time, these charges will bring clarity as to whether the bank regulations of today are sufficient, or if regulations need to be tightened to protect freedom of expression.”

It’s not just WikiLeaks that has been hurt by the randomness of the payment service providers. Swedish entrepreneurs such as sex toy shops and horror movie stores have also been denied payment services arbitrarily, which has effectively been a death sentence for the fully-legal companies.

Johan Terfelt, who oversees the Finansinspektionen unit for payment providers, confirms that the authority has received the filed charges, writes the Dagens Nyheter:

“We will now investigate what has happened and evaluate the reasons, if any, for us to intervene”, Terfelt tells the Dagens Nyheter. He also states there’s no room at all for arbitrary randomness, and gives a careful hint at a possible outcome: “The law states, that if there aren’t legal grounds to deny a payment service, then it must be processed.”

More in ye Swedish Oldemedia: the Dagens Nyheter, the Göteborgs-Posten.

The Copyright Monopoly Is A Market Distortion, Not A Birthright

Copyright Monopoly: When you start questioning the copyright monopoly, many middlemen and other has-beens start acting offended – as if you have somehow questioned a natural right that they have by birthright. Nothing is farther from the truth.

The copyright monopoly is not a natural right. It is a government-sanctioned private monopoly, granted under the assumption that no culture would get created if there’s not a profit motive behind it, and that this profit motive can only be realized in a monopolized setting. Yet, when you question this assumption and this monopoly, some people react with unmitigated angry and fury – as though you have questioned their very right to life. This is puzzling, and indicates a lack of understanding of what the monopoly is and why it exists.

(People who like liberal capitalism should balk at “goverment-sanctioned monopoly”. People who lean towards labor values should balk at “private monopoly”. Still, it’s factually true.)

If property rights and normal competition were applied in the fields of culture and knowledge, there would be no such thing as the copyright monopoly whatsoever. It would be like any other field of entreprenurship – compare, for example, with how a professional chef needs to create new recipes and then can monetize them either by performing, by educating others, or by selling cookbooks, just to name a few methods. I use chefs as example on purpose here, as food recipes are explicitly not covered by the copyright monopoly – and yet, there are many cooks, chefs, and famous star chefs.

Some time in history (in 1709, specifically), publishers managed to convince legislators that no culture would get printed and distributed if the publishing guild couldn’t get the copyright monopoly reinstated, the lucrative monopoly that had previously been a censorship regime. Importantly, they didn’t argue that nothing would get created without a monopoly; they argued it wouldn’t get duplicated and distributed. Thus, fearing that no culture would be available for the population, legislators agreed to the monopoly on purely utilitarian grounds.

Later, this mutated into a purely utilitarian justification for this monopoly that limits normal property rights, competition, and trade mechanisms: “without the monopoly, little or no new culture would get created”. We see that all the time: “if you allow this monopoly to last for only 110 years instead of 120, how would the million-euro blockbuster movies get funded?”. Putting aside the argument that no movies have a return-on-investment horizon of 100 years in the first place (and many actually make their investment back opening weekend, making the copyright monopoly completely unnecessary), this argument keeps coming back: “if there’s no monopoly, no culture will be created”.

Thus, any entrepreneur aspiring to sell culture by the copy has historically had two layers of customers, and keeps having two layers. The first layer is legislators, where they have to keep selling the idea that the greater public good is served by giving the culture entrepreneurs a monopoly that infringes on other people’s property rights (“or culture won’t be created at all”). The second layer of customers are the ones actually buying culture by the copy.

That’s why it’s so thoroughly surprising to see these entrepreneurs react with fury and anger when legislators who are actually their customers – even if just customers of an idea they keep entertaining – when those legislators question the existence and value of this monopoly, up to and including threatening in public to burn such politicians at the stake. The copyright monopoly is not a natural right, like property or life. It never was. It is a government-granted market-distorting privilege that limits property rights and limits trade.

If entrepreneurs in the cultural sector want to keep this distortive privilege, the utilitarian value of it needs to be re-evaluated constantly. It is usually a bad idea to threaten the people who ultimately get to decide if the monopoly remains, rather than attempting to keep selling the picture of it as something that serves the greater good.

Of course, we also know now that the original premise of the copyright monopoly is thoroughly false. People are creating more than ever, and despite the copyright monopoly, not because of it. Over two days of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute. People create as much in 48 hours today as humankind had created in total before 2003. Granted, not all of it is blockbuster movies – but humankind’s favorite form of culture has always shifted with the times. We don’t watch opera or theater much any more, so perhaps there’s something very interesting around the corner that will replace blockbusters, too?

In any case, the copyright monopoly is no kind of natural right, and people who react with fury and anger when it is questioned are severely misguided. They are reacting quite like religious fundamentalists. I don’t mean that in the sense of what we normally associate with a religion, I am merely pointing out that they are behaving in exactly the same patterns as religious fundamentalists are: with anger and hostility, every time their claims are called into question and scrutiny.

Just like with religious fanatic zealots, that disapproval of scrutiny may ultimately be their downfall – so may the light of a thousand suns shine on the disastrous market distortion that is the copyright monopoly.

This article is also published on TorrentFreak.

December 16, 2012

Minor Technical Problems

Metaposts: Some minor technical problems caused the translated parts of the site to go haywire late yesterday and post everything to the English feed. Apologies for that. We have restored to a backup before this deviation and are monitoring the situation if the problem reappears.

This is why you got five new articles in FoI yesterday that were in non-English languages.

December 13, 2012

Four More Reasons The Pirate Bay Is Effectively A Public Library – And A Great One

Infopolicy: File sharing fulfills the exact same need and purpose as public libraries did when they first appeared, and is met with the exact same resistance – even in the same words. This article follows the previous observation that The Pirate Bay is the world’s most efficient public library.

Zacqary Adam Green’s piece comparing The Pirate Bay to the New York Public Library the other day was spot on, and we’ve seen it travel a lot around the world – in excess of 3,000 shares and counting. File sharing (and The Pirate Bay) is the most efficient public library ever invented, and its invention is a quantum leap for civilization as such. Imagine every human being having 24/7 access to humanity’s collective knowledge and culture!

Moreover, it’s not even a pipe dream that needs to be funded with forty gazillion eurodollars. All the technology has already been developed, all the infrastructure has already been rolled out, and the tools already distributed. All we have to do to realize this is, frankly, to remove the ban on using it.

In the book The case for copyright reform (download here), we can read the following:

We now know that the arguments against public libraries were wrong. It quite obviously did not lead to a situation where no new books were written, and it did not make it impossible for authors to earn money from writing. On the contrary, free access to culture proved to be not only a boon to society at large, but also turned out to be beneficial to authors.

The Internet is the most fantastic public library that has ever been created. It means that everybody, including people with limited economic means, has access to all the world’s culture just a mouse click away. This is a positive development that we should embrace and applaud.

However, in highlighting that file sharing is essentially a modern public library (and a radically efficient one at that), four specific objections always appear – four objections that aren’t factually true, so let’s take a look at them one by one and why they aren’t correct.

Incorrect objection 1: “Libraries pay money to authors for each lending.”

This objection would invalidate file-sharing-as-a-library by pointing at the fact that libraries give money to authors on each lending, something that doesn’t happen with file sharing. The problem is that the objection is factually incorrect. Authors do not get money each time their book is borrowed.

In many places in Europe, there is a unilateral cultural grant given to authors and translators in the national language when a book is borrowed – not given by libraries, but measured on library loans. It’s not compensation for loss of imaginary income but a cultural grant to promote national culture, and most importantly, it doesn’t go to the original author but to the last link making the book available in the national language – be it the author (if the book was written originally in that language) or, in the vast majority of cases, the translator.

In other words, when somebody borrows Harry Potter in a Swedish library, J.K. Rowling doesn’t get a single cent from the Swedish författarpenning. This is the model in all European countries I’m aware of.

Furthermore, this cultural grant was introduced in the 1940s to 1960s across Europe – almost a century after the public libraries.

Incorrect objection 2: “No author would ever agree to not getting a cent when books are borrowed from libraries.”

This is a mind-boggling objection. The copyright monopoly is a limited monopoly on duplication and performing – and it certainly doesn’t give somebody the right to dictate how a book may be used or not used once it’s sold to somebody. A buyer of a book has every normal property right associated with a book they buy, including tearing it apart, using it as a doorstop, or lending it to a friend or stranger – just not those normal property rights taken away by the copyright monopoly, namely certain cases of duplication and performance.

That an author or publisher would somehow have a say in how the objects are used once they are sold is completely foreign to how trade works. (Nevertheless, publishers once demanded lending of books between people to be banned by law, arguing that lending books between people was stealing from the author, and that everybody must buy their own copy. Parliaments across Europe asked them to take a hike and opened public libraries instead.)

Incorrect objection 3: “Libraries pay for the culture they share with the public.”

Indeed they do. So does every file-sharer who buys a copy of a particular cultural work, re-encodes it digitally and optimizes it for distribution/file-sharing, and shares it online with the world. No difference in principle whatsoever there, only in efficiency – but that was the whole point, wasn’t it?

Incorrect objection 4: “Libraries buy a finite set of copies and lend only them.”

This is a somewhat tricky one. While technically true, it is based on the misconception that the function of libraries is to lend things to people. That’s not their function. Their function is to make culture and knowledge available to as many people as possible for free.

This can be observed in the political discourse when libraries were once created, and compliance with the copyright monopoly was a non-objective: laws were changed to make sure that libraries were completely unhindered by the copyright monopoly. (These laws remain today for the most part – you can find exceptions for library use in most countries’ copyright monopoly laws.)

Rather, the reason there is a check-in/check-out system of books is that it was the most efficient mechanism available at the time to make sure that as many people as possible had access to culture and knowledge without having to pay for it. It has nothing to do with the copyright monopoly at all – it was (and is) simply a guarantee that the library would be able to keep sharing culture to the masses without forcing them to buy their own copies of the culture and knowledge in question.

In conclusion, file sharing is the most efficient public library ever created. That’s an amazing feat of humanity, and something to be celebrated. Those parasitic middlemen who stand in its way need to take a step aside, either voluntarily, or be forced to by law – as was the case when public libraries were first created.

December 10, 2012

The Declared Value System: Managing Monopolies for the Public Good

Copyright Monopoly – Karl Fogel: What would a truly free-market approach to copyrights and patents look like?

The problem we have right now is this:

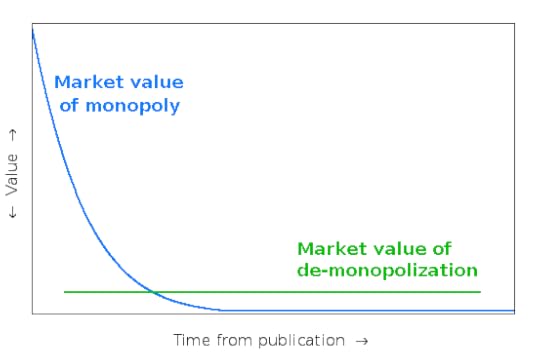

The flat green line represents the value to the public of de-monopolizing the work — think of it as “what the public would be willing to pay for unrestricted access”. The point where the curved blue slope crosses the green line is the point where there is no longer any public or private purpose to having a monopoly. From that moment on, the value of the monopoly to the rights-owner is equal to or less than the value of de-monopolization. Yet today, the monopoly continues beyond that point. The green line is simply ignored in the current system: we pretend it does not exist.

(The graph is a simplification, but not in ways that matter to this proposal.)

You might think there’s already a market solution. After all, in the current system, anyone could in theory be offered a fixed sum to liberate their work into the public domain [1]. But markets don’t quite work the way we’d hope. This is is why we have eminent domain in real property, for example. As soon as someone starts talking about building an airport in some farm fields, all of a sudden every farmer decides their field is worth ten times as much as it was the day before, such that no airports could ever be built if we did not use the pre-rumor valuations. It is the same with copyrights and patents: the mere expression of interest in re-use drives up the price instantly, and the perpetual optimism of rights-holders ends up stretching their monopoly past its natural market end — hurting everyone else and preventing further re-use, yet frequently without realizing the benefit the rights-holder hoped for. We all lose.

But unlike with land, there’s a way out, because there’s a third thing we can do besides sell or not sell: we can liberate. That makes all the difference.

The Declared Value system

Suppose things worked this way instead — I’ll use copyrights for the sake of discussion, but this applies to patents too:

A new work gets an initial automatic copyright term, as it does today but much shorter: maybe a few weeks or months from publication, enough to ensure there’s time for the owner to register the work if they wish to extend the monopoly.

If the copyright owner does not register, the work simply enters the public domain [2].

But there’s an alternative: instead of letting the monopoly lapse, the copyright owner can choose to register the work for continuation of copyright (renewable annually), with a registration fee proportional to the self-declared value of the work. That is, the copyright owner picks a number of dollars (yuan, euros, whatever) that she claims the work is worth. It can be any number at all, but the yearly registration fee will be a percentage of it — for discussion’s sake, say 1%. The exact proportions don’t matter here: it could be 0.5% or 2% instead of 1%, registration could be semi-yearly instead of yearly, etc. The idea is the same, regardless of how you set the knobs.

Now comes the key:

Since that declared value is now a matter of public record, anyone can pay it to the copyright owner to liberate the work into the public domain. This is not a purchase. People would still be free to sell or lease their copyrights, for whatever price they can get (which, interestingly, may be higher or lower than the registered value — the market dynamics behind that decision are just as rich as those involved in determining exclusivity value under today’s copyright system). But whoever the owner is, whether the author or someone else, they’re responsible for keeping up the registration. And while the work is still under registration, anyone can come along and pay the registered owner the declared value to liberate it.

Liberation, unlike purchase or lease, is a mandatory transaction. The justification is that since the registrant chose the price in the first place, it is by definition fair: it was self-declared. Furthermore, these are after all public monopolies, and the public’s ultimate interest is in having works be available without restriction. For governments to hand out monopolies with no escape clause has always been an abdication of responsibility. If there is a way to fix that, we should take it.

The copyright holder has an incentive not to declare too high a value, because she’ll have to pay a percentage of it to register; she has an incentive not to declare too low, because then someone will come along and liberate the work very quickly at a low price (though some artists will find that liberation is economically a better deal for them anyway, and simply not register, or register at a declared value of zero in order to get a timestamp for attribution purposes).

Because the value of a work may change over time, the registrant may adjust the declared value up or down each year when renewing the registration [3]. This is also one of the reasons behind that brief initial registration-free monopoly term: it gives the copyright holder a chance to judge the work’s monopoly value, information she can use to decide how much to register the work for.

Whether indefinite renewal should be available is an open question. Personally I think not, for two reasons: first, because there has simply never been a compelling argument for perpetual copyright and most jurisdictions do not have it. Second, because awareness of an approaching horizon will pressure registrants to set lower liberation prices as that horizon comes closer — which is the right direction for things to move, from the public’s point of view, since even the most confident authors cannot reliably predict years ahead of time which monopolies will remain valuable, and therefore far-future valuations do not have a significant incentivizing effect anyway.

But even if indefinite renewal were permitted, the system still has desirable effects. The tendency of monopolies to accumulate in media conglomerates (who then press for Internet censorship to preserve those monopolies) would be greatly lessened by the cost of maintaining all those registrations. Forced to choose which assets are really valuable, the companies would have to lower the liberation values for many works, thus providing the fertile ground for re-use and innovation that artists, other publishers, and the rest of us are denied under the current system.

On “Balance”

While this proposal is a compromise, it’s at least a compromise tilted toward the public interest. By analogy, think of a homeowner who cuts a driveway opening onto a public street in order to gain access to a private garage. If I take a streetside parking space away from the public, I expect to pay the city (that is, the public) a fee, and usually annually, too, not just a one-time fee. Similarly, a copyright owner who wants to keep a work out of the public domain should pay for that privilege. But unlike a garage, this privilege need not be permanent, because losing monopoly control over a work is not as serious as losing one’s indoor parking space.

This system would go a long way toward alleviating the orphan works problem, by ensuring that the copyright owner of a work could always be found (someone must be paying the fees over at the registry), and toward alleviating the ghost works problem (in which derivative works are suppressed), by setting a maximum amount of money that, in the age of Kickstarter, would usually still be attainable by a motivated party who wanted to see that work in the public domain.

The copyright lobby frequently talks of finding an appropriate “balance” between the needs of creators and the needs of the public. Like many appeals to balance, it is a smokescreen for something else: in this case, for efforts to increase copyright terms and restrictions beyond their already absurd lengths. The “balance” they’re talking about neatly presupposes that creators and the public are somehow on opposite sides, while multinational content monopoly conglomerates are, curiously, absent from the picture altogether. (Their portrayal is also historically suspect, as copyright was primarily designed to subsidize distributors not creators anyway.)

Thanks to this focus on exclusivity-based balance, proposals to improve the system are usually minor tweaks: broader “fair use” rights, a more thorough prior-art discovery process, various changes in scope, etc. But these approaches leave the basic problem untouched: when a copyright or patent is granted today, it creates a monopoly with no countervailing pressure towards a true free market.

There needs to be a market-based representation of the value of de-monopolization, expressible by those whom de-monopolization benefits. In Macaulay’s famous words, “the effect of monopoly generally is to make articles scarce, to make them dear, and to make them bad.” [4] Anyone familiar with, for example, the mess George Lucas made of his monopoly on the “Star Wars” movies will instantly see Macaulay’s point. The problem is not that Lucas botched the sequels, but that the Lucasfilm monopoly prevents anyone else from doing better. This is the problem with monopolies generally — it’s not what they let the monopoly owner do, it’s what they don’t let others do. Monopolies are the opposite of free markets.

The Declared Value system introduces de-monopolization as a market force, without involving the government in pricing decisions, term-length calibrations, or other arbitrary regulatory judgements [5]. The system takes “balance” seriously: it gives the rights-holder a decisive role in setting a valuation and benefitting from it, but at the same time represents the public’s interest in not having works monopolized forever. Crucially, it avoids the need for complicated regulatory formulas, which would inevitably create a target surface for monopoly interests to aim lobbying power at. Instead, it gives the public a mechanism for representing its own interests directly, with the government limited to a bookkeeping role.

The proposal is not merely rhetorical. I would be delighted, if surprised, for it to receive legislative interest. But it is also meant to expand the range of the possible. Fiddling with copyright term lengths and improving the Patent Office’s processes feel good, but they are fundamentally repainting a burning barn. To get lasting improvement, we need to permanently reduce the “lobbyability” of the system as a whole. The Declared Value method is one way to do that [6], and to show that market-tempered monopoly is possible in principle. It’s high time these kinds of solutions were on the table.

References:

[1] I’m using terms like “public domain” loosely here. That term is usually used in copyright law, not patent law, but it’s easy to intuitively understand what it means for patents: that no one has a monopoly, that is, there is no one with the power to restrict usage.

[2] There should be nothing shocking about this: the public domain is the natural destination for works, and even most proponents of lengthening copyright and patent terms pay lip service to that goal. Furthermore, registration requirements used to be the norm if one wanted to hold any public monopoly. Indeed, the requirement for copyrights was only eliminated under the theory that insisting on registration gave advantage to corporations who had economies of scale to streamline the paperwork involved in filing — which was probably true, in the days before the Internet, but today registration would be as easy as uploading a file and receiving a digitally-signed timestamp.

[3] Alternatively, the owner could be allowed to adjust the declared value at any time (perhaps even as a reaction to liberation offers), with the provision that any upward adjustment would require immediate payment of the difference between the old and new registration fees. However, the public domain would probably be better served by simply allowing adjustment only at fixed intervals: if the owner of a work can’t figure out its market value and set the fee accordingly, that is no reason to favor the owner over the public when the work is being liberated at a price the owner clearly once thought sufficient.

[4] en.wikisource.org/wiki/Copyright_Law_(Macaulay)

[5] One of the problems with not having a systematized and predictable path to de-monopolization is that we instead get unpredictable decisions like India’s decision to set a compulsory license rate on a drug still under patent. The point is not that the Indian government made a mistake — the decision was quite defensible — but that handling each such instance as a special case inevitably leads to lack of predictability and, eventually, to corruption. Yet it’s governments that issue patent monopolies in the first place: if they can set compulsory license rates in specific cases, then they can offer a mechanism for de-monopolization in the general case.

[6] My colleague Nina Paley has suggested a simpler system: bring back registration, and set the fee for the first year at $1, the second year at $2, the third year at $4, then $8, $16, $32, $64, and so on. This has the advantage of immediate comprehensibility, and it’s clearly effective at tempering the monopoly: very few works would remain restricted past the 20 year mark, and her system doesn’t need to be adjusted for inflation for a long time.

December 8, 2012

It’s Not “Getting” Or “Downloading” A Copy. It’s “Making” Or “Manufacturing” One.

Infopolicy: In the political fight for civil liberties and sharing culture, language is everything – which can be observed by the copyright industry’s consistent attempts at name-calling, hoping the bad names will stick legally. Therefore, all our using precise language is paramount for our own future liberties.

When people are saying “I downloaded a copy of Avengers“, that use of language erodes their liberties just a little bit further. It is wrong, as in technically and factually wrong. Looking at the use of “downloading a copy” or “getting a copy” and how this is incorrect, we need to examine why it is important to use other words.

For that’s not what happens. “Getting” or “downloading” doesn’t describe the process. No copy pops onto the wires, travels through the net, and sets itself on the hard drive on the person’s system. This is the copyright industry model of reality, their fake model, which they use to push for harsher laws and erosion of liberty. This is how they equate “stealing a copy of the Avengers” with “stealing a gallon of milk”. That the object is somehow stolen through the internet. That’s not what happens.

What really happens is that you have instructed your system to listen to a complex series of protocol packets, and using them as instructions, you manufacture a copy at your end. You are making a copy using your own resources and property, by listening to instructions online. If nobody listened to these instructions at the time, no copy would get manufactured. The copy isn’t downloaded, it is manufactured. This technical distinction is crucial for three reasons of net liberty.

The first reason is language. Compare the following four sentences:

“He downloaded a copy of Avengers for free.”

“He got a copy of Avengers without paying for it.”

“He manufactured a copy of Avengers for free.”

“He made a copy of Avengers without paying for it.”

It quickly becomes obvious that the first two are reinforcing the copyright industry’s “stealing” moniker, with a clear tone of dishonesty, whereas the second two just don’t work in that aspect – if anything, they have a “yeah, so?” tone to it. Using making and manufacturing makes it clear that you are not expected to pay money in the process, whereas “getting” implies the opposite. Therefore, it is important to use the technically correct making or manufacturing.

The second reason is that it reinforces that the copyright monopoly is indeed a monopoly, and not property. When we say,

He manufactured a copy of Avengers without paying

it becomes very clear that manufacturing a copy is something fairly normal, but that somebody is expecting protection money for us doing so. That is miles and leagues from the copyright industry’s idea that all copies are somehow their property, where things are somehow “stolen” through the net.

The third reason is that proper use of language reinforces that the copyright monopoly is a limitation of property rights, rather than being the magical subset of property that the copyright industry would like. When we say

He manufactured a copy of Avengers

it becomes obvious that this was made from the person’s own raw materials using their own time, and if a law says that this cannot be done, then that law is interfering with how we can use our own property – so it illustrates how the copyright monopoly is a limitation of property rights.

It’s not “getting” or “downloading” a copy. It’s making or manufacturing one.

December 7, 2012

The Pirate Bay Is The World’s Most Efficient Public Library

Infopolicy – Zacqary Adam Green: The way media piracy works is that one person or group purchases a work, and then shares it with millions of other people. This supposedly deprives the author or artist of those millions of people’s money. One group has acquired over 50 million media items, and makes each of them available to approximately 20 million people — which must be a tremendous hit to creative professionals’ wallets. This notorious institution is called the New York Public Library.

It begs the question why every author, filmmaker, and musician isn’t up in arms about the New York Public Library’s rampant sharing, while there’s a ton of opposition to the sharing habits of BitTorrent peers who use The Pirate Bay. After all, The Pirate Bay’s community shares significantly less than the New York Public Library: just 1 million items in 2008 (and the collection certainly hasn’t grown 5000% since then). The reason that The Pirate Bay is offensive, and the New York Public Library is not, is because of its efficiency.

Before the New York Public Library can share an item with you, you first need to schlep all the way to 5th Avenue and 42nd Street in Manhattan. Then you have to walk around the massive building to find what you’re looking for. That is, if the item isn’t checked out. See, the New York Public Library has a peculiar system of storing their items: in finite, physical form. If you want to read a book or watch a film, there are only a few copies available. You can take an item home for a limited time (which forces other people to wait until you return it), but only if you live in New York State.

The Pirate Bay, on the other hand, requires you to type in a search term, click on a download button, and wait a little while. There’s no scarcity, no residency requirement, and you can do it from anywhere with Internet access. Significantly more efficient.

Either way, whether you read a library book or a torrented e-book, you no longer have to give the publisher any money. This has historically been okay, because in spite of everything, libraries haven’t killed publishing.

Physical public libraries — like the New York Public Library — are universally thought of as good for society. They provide free, open access to knowledge, culture, education, and even just entertainment to millions of people around the world. Anyone who demonizes the mission of these libraries is usually regarded as a wingnut, and not taken seriously. But it’s fairly mainstream to rail against filesharing sites like The Pirate Bay, Tuebl, and Take.fm. All these sites are doing is the same thing as brick-and-mortar libraries, but more effectively.

This is a comparison that really ought to have been pushed back when Napster was on the evening news. Filesharing sites and services are the most radically efficient public libraries that humanity has ever created. Never before has anything been better at giving the public open access to culture and knowledge. Mission accomplished. Why is this suddenly a bad thing?

If free and open access to all of human knowledge at the push of a button truly prevents our society’s beloved artists, authors, thinkers, and other creative people from putting food on their tables, then maybe it’s time to rethink how to put food on their tables.

November 30, 2012

When Did It Become Our Job To Fix Their Business?

Copyright Monopoly – Jack Zeal: I was arguing with someone on Reddit recently over monopoly reform, and instinctively, I started to say “There are a whole galaxy of other business models than selling undifferentiated copies and precluding anyone else from undercutting you.” The key word here is instinctively. If you support reform to current copyright monopoly laws, you spend a lot of time saying that there are other business models.

The Techdirt crowd, for example, embraces the message of “Connect with Fans and Provide a Reason to Buy”. Falkvinge.net is also filled with posts about people embracing “alternative business models” and succeeding. However, is this where we want to keep the discussion at, forever?

If we propose specifics, we leave ourselves vulnerable to the “but what about A or B? Those couldn’t work with business model C!” It’s an unending cat-and-mouse game. The classic example is the old “How to finance a blockbuster-caliber movie?” trope. Nobody ever considers that maybe the current system is the reason movies have to cost that much, do they?

If we offer generalities, like “Merchandise and sell experiences instead of commodities”, they tend to be shot down in snarky sound-bites, like “So bands will have to sell T-shirts instead of records?”

It keeps the conversation on the content industry’s terms. They can be the “victims” needing a “rescue” strategy. It’s sure a great shift of attention from the rest of society being denied access to information and the natural rights to communicate and share.

It’s needlessly speculative. Indeed, it reminds me a lot of the earliest “home computer” books dumped out by the thousands in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The authors spent hours arguing that we’d all be managing recipies or doing computer-driven teaching, and then VisiCalc happened and people forgot all about recipe-management. No doubt it will be the same. Someone finds the “killer model” for post-monopoly revenue generation, but it’s probably not gonna happen until there’s no other choice but to find one. And much like the cuddly toy in the caption image, some of the suggested models aren’t gonna fly in the real world.

Admit It

You opened this article to figure out what sort of point I was making with that picture. That shows a viable business model there– weird, custom images to be used as teasers on blogs. Oh, great, I’m starting again…

Let’s stop playing defense.

It’s not our job to figure out how to fix their business models, especially when said business models are based on faulty or untenable assumptions. If you’ve been trying to grow oranges in Alaska, and make up the difference with farm subsidies, the end of subsidies is not a punishment, it’s well-deserved justice.

Instead of answering the same question every third discussion, it’s time to turn the moral argument on its head. “Is it worth it to deny us every piece of art since 1923 to ensure Lady Gaga will be able to get five Bentleys instead of three?” I’m waiting for an answer…

Rick Falkvinge's Blog

- Rick Falkvinge's profile

- 17 followers