Rick Falkvinge's Blog, page 31

January 8, 2013

How the Police and Politicians Can Regain the Public Trust

Corruption – Andrew Norton: A few months ago, I asked what we should do about law enforcement officials that broke the law in a piece called “Is it time to police the police?”. It’s taken me some time, but now I’ve compiled the responses and got some suggestions to float to the global hive-mind that peruses FoI.

First, let’s be clear. Not all cops are ‘dirty’, but at the same time, not all citizens are criminals. Yet since it’s considered acceptable that in many western countries, you have to prove you’ve done no wrong to a police officer, rather than they have to prove a criminal act has been committed, it’s only fair to consider them the same way.

So let’s start with some processes. In many police jurisdictions, when a police officer is suspected of a crime, or malfeasance they are generally suspended on full pay, or put on ‘desk work’. A criminal act would be investigated, an arrest made, and most jobs won’t pay you if you’re sitting in a cell. In the UCDavis pepper-spraying, we saw Lt. Pike do it. In the Tomlinson case, there was video evidence that he was attacked by an officer unprovoked. Both officers were kept at full pay during the investigations.

CHANGE – Where there is prima facie evidence that a crime has been committed, he should be suspended from his job, and treated like any other criminal. No working as an officer (or security guard), no badge, no gun, no perks, no pension, and no pay.

While some will say it’s harsh, it’s no more than the rest of us face. And it may return a measure of ‘think first’ to those on the job, who won’t be assured of a lengthy paid vacation if they’re caught doing what they shouldn’t. Additionally, police officers are often not keen on their actions being documented. Many officers in the US have tried to apply wiretapping statutes to recordings of officers performing their duties (yet again, they can record you and be exempt from the same laws). Also, some states have forces that are less than ‘open’ with their recordings. In Oklahoma, for instance, police dashcam recordings are classed as records for the purpose of the open records law, with one exception, state troopers, and now judges in that state have been expanding on it.

CHANGE – Any attempts by officials to prevent, halt or damage recordings without good reason (such as it actually impeding the arrest) to be charged with the relevant evidence tampering or investigation impeding laws. All officer camera footage (be it mounted in a room, on the officer or a piece of equipment) is to be considered an open record for the purpose of all relevant laws, while still being mindful of data protection and privacy statutes.

Next, let’s talk about malfeasance. Officers are known to commit criminal acts, knowing that their profession lets them get away with it. When things come to trial, often the ‘good conduct’ of an officer is cited as a mitigating factor. However, in a job, that allows powers beyond those available to the citizenry, the fact you’ve done it for years without a problem isn’t a factor. What is a factor is the extreme breach of the public trust placed in you when you took your place in that job. To quote Spiderman, “With great power, comes great responsibility”.

CHANGE – Where an officer of the law (which includes prison guards, and judges) commit a crime on duty, or use their position to influence things or ‘get out’ of punishments (such as an off-duty LEO flashing a badge to get out of a speeding ticket), then the crime is modified to be one committed ‘under colour of authority‘. A modification of minimum and maximum sentencing guidelines to take into account the breach of public trust, by abusing their position for crimes committed “under colour of authority”. I would suggest a 50% increase in both.

Weapons are the main difference between law enforcement and civilians. In countries like the UK, they’re the only ones armed legally. But on top of firearms, you have other weapons that are prohibited from civilian use/possession or are under extremely strict regulation. That’s everything from Pepper/CS/PAVA spray, through batons (side-handle, extendable/ASP and traditional truncheons/billyclubs) electro-stun (including tazer), less lethal rounds, and vehicles. Then there’s the radio, which can call another dozen or more officers, also similarly armed, all amped up and ready to go because of what they’ve been told.

Often these are used to threaten, or otherwise in accordance with their legal, intended use. Of course the textbook is again, Lt. Pike with the pepper spray, there was also the Oakland occupy incident shortly before that, where a protester was targeted and struck in the head with a beanbag round; the punishment? A year later, he might lose his job. No criminal charges, no loss of pay, just the job, a year later. Meanwhile a similar attack on a police officer is considered so serious, a Congressional Bill has just been submitted concerning ‘Blue Alerts’ when an officer is seriously injured or killed. It’s hypocrisy of the highest order.

There are amazing numbers of cases each year of excessive force, and the growing trend now is to use Tasers to bring events to a swift conclusion with the officer in control. In one 2005 incident, a man was tasered over 30 times, according to news reports. No disciplinary action was taken, and it took months to even get his effects.

2005, when they were still being introduced to law enforcement at large, was a bad year for taser-victims, but not cops. In a California case, Bryan v. McPhearson, the court decided the officer’s actions qualified under the doctrine of qualified immunity (cops will only be responsible for excessive force if they act in a way that is so unreasonable any cop would have known such conduct was against the law – basically acting criminally) Since ‘the law on taser police brutality’ was still evolving when the incident happened in 2005 the cop should get a break from liability. You read that right, because no-one had told the cop, he didn’t have any notion of right and wrong. Ignorance is an excuse, if you wear the badge. In 2005 incident, a man was tasered over 30 times, according to news reports. No disciplinary action was taken, and it took months to even get his effects.

It’s this that characterizes many police brutality and excessive force cases. On one hand the police officers are professionals dedicated to knowing and enforcing the law, when they’re on the prosecuting side, their word is solid and their testimony is unquestionable. However if they’re a defendant, they’re amateurs who don’t know the law, can’t tell right from wrong, and whose training and instincts are so poor, that they can’t be held responsible for decisions made when doing their job because they have to do them quickly.

CHANGE – Convictions of violence/brutality/excessive force under colour of authority are to be treated as the serious violent criminal acts they are. If the act was not reactive, and especially if prolonged, or needlessly escalated (When you use a weapon before a less confrontational method for instance, or a weapon deliberately misused) then it should be considered a murder/attempted murder case (depending on the status of their victim). Likewise any deaths in custody are to be considered suspicious at all times.

Next, investigations into acts called into question are often done informally, and internally. There are ‘nod-and-wink’ investigations where a semblance of scrutiny is given, but in reality it’s a smokescreen. Meanwhile colleagues tend to close ranks, resorting to the omerta typified by the Mafia, better known as “no snitching”. This is an attempt to subvert the law, by denying evidence. The intent is often portrayed as one of ‘trust’ (as in ‘I trust he has my back by covering up’) with the result that evidence is suppressed, or made contested.

CHANGE – All investigations are to be meticulously detailed, such that another investigator, even from across the country, can follow-up on the investigation if needed. Failure to do so would leave the investigator likewise subject to investigation for their actions. Officers attempting to lie, cover up, or obstruct the investigation to be charged as co-conspirators in the crime, in addition to the relevant charges for obstruction/perverting of justice, and dealt with as above.

Once under investigation and where it looks to succeed, many officers elect to retire, or resign, to avoid, or reduce punishment. While the decision to resign is certainly their prerogative, it should not be construed as an alternative to investigation and punishment. At no other area do you get to walk away from crimes by quitting. If you work at a regular company, and get caught stealing, you don’t say ‘well, you don’t need to charge me, I’ll quit’ (unless you’re the CEO, but that’s a whole other topic) yet in both the justice field, and politics, it’s considered acceptable, and sometimes ‘noble’.

CHANGE – No retirements permitted while under investigation; would have to wait until exonerated. Resignations are acceptable, but it in no way affects the course of the investigation. No investigation is to stop because the person or persons investigated have left their position. If the investigation is substantiated, then the penalties are the same as if they were still employed, because the later state of (non)employment has no bearing on the actions while employed.

Finally, some people get in trouble, get out of the job, and then come back. This has happened with police officers (the officer in the Tomlinson case was involved in a violent incident in the 90s, quit, joined a different police force years later and then transferred back to London) but is also common with politicians (See Silvio Berlusconi). Diseased limbs aren’t given back to patients or left in the open. Once they’re removed they are then destroyed. That way reinfection is minimised. At the same way, a stigma must be placed on these actions, and people MUST be aware of their level of untrustworthiness, and that they have abuse a public position.

CHANGE – Investigations and their documentation (see above) are to be recorded. Any person with a ‘colour of authority’ conviction is disqualified from any position of public authority.

OPTION: A register of, let’s just say ‘Corruption’ (while the term isn’t accurate, neither is the term ‘sex offender register’ when a significant number of actions that get people on it are not sexual in nature) which are public record.

What we have here are a number of measures that basically enhance the requirements to investigate criminal acts by those in a position of responsibility; politicians as well as law enforcement and the judiciary. The problem of corruption, not just financial corruption but moral and authoritarian corruption is becoming endemic.

These solutions are not overly radical; they amount to treating abuse of public office as being serious crimes in themselves, on top of the crimes committed. Some might say it’ll lead to officers and politicians second-guessing themselves, but they’re not being asked to follow new laws, just the same as everyone else. No police officer will let someone off a crime because ‘they were under pressure’. “I’m sorry I beat him with a big stick but I was under pressure and it was a split second decision” will get you off only if you’re a police officer.

If it makes people stop and consider their actions first, that’s all to the good. In exchange for the power they’ve been given, they also have to accept the consequences, and enhanced punishments when they’re caught doing wrong is one of them. You can hand out punishments, but don’t want them imposed on you? Tough, find a different career.

The intent is deterrence. When you can get away with a crime, knowing that any investigation won’t do much, you’ll be getting full pay for it, and that your buddies will back your version; there’s no incentive to behave within the law. When those tasked to implement or uphold the law have contempt for it, what chance do ordinary people have?

It is time to make it clear that corruption, malfeasance, bullying and swaggering arrogance is no longer acceptable.

While many officers (and politicians) won’t like these kinds of rules and claim it hampers their ability to work because they’re afraid of the consequences, that’s exactly what it’s like for ordinary people, day in, day out. And we’ve now seen the kind of behaviour not having these rules has engendered. There’s a lack of respect for police officers now, and for politicians, and it’s because the rules don’t seem to apply to them anymore. It’s time to change that. If you’re good, and honourable, and follow the law, you’ve nothing to fear. After all, you willingly took on the added abilities, now you get the added punishments if you abuse them. That’s only fair.

Meanwhile, this won’t magically restore the public trust in politicians and law enforcement, but it will address one of the biggest problems that has eroded it. Decades (centuries in some places) of abuse can’t be ignored overnight, but by taking responsibility and ‘cleaning house’, it can happen.

January 7, 2013

Is The Copyright Industry Really Shooting Itself In The Foot?

Lobby Efforts – Zacqary Adam Green: It’s tempting to mock the copyright industry for being unable to understand the Internet. Why, we ask, do they sue their fans, play whack-a-mole with torrent sites, and push for net-restricting legislation that savvy users can easily get around? Why don’t they just change their business model? But we never ask these questions expecting an answer; we just want to laugh at how stupid they are. Maybe they’re not. Maybe they know exactly what they’re doing.

It’s said that we should “never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” The copyright industry’s behavior is not adequately explained by stupidity. It’s filled with people sapient enough to dress themselves in the morning. Their strategists, accountants, and lawyers are well-educated. They know how to use a computer. They read Techdirt and TorrentFreak. They’ve heard our side of the debate.

The industry has considered changing their business model. They’ve run the numbers, believe me. And the numbers don’t add up. There is no way in which Viacom, Warner Brothers, and Disney can coexist with a free and open Internet.

The copyright industry doesn’t need us to tell them that piracy isn’t a problem. They know. We don’t need to tell them that people will still go to concerts and movie theaters even if they can get it at home for free. Their spokespeople who seem not to know any of this are lying.

They are not afraid that The Avengers is on The Pirate Bay. They are afraid that Adobe Premiere and Final Cut Pro are on The Pirate Bay. They’re not afraid of people creating YouTube videos with popular music in them without paying a licensing fee. They’re afraid of people creating YouTube videos, period. They’re not afraid that their music is on SoundCloud. They’re afraid that your music is on SoundCloud. They’re afraid that you can mix an album with software that ships standard on every new Mac. They’re afraid that for the price of a high-end laptop, you can buy a video camera that rivals $100,000 Hollywood cameras, in image quality if not resolution. They pray to god that you’ll never get any good at using Blender. They’re petrified of Kickstarter.

Deep down, the copyright industry isn’t all that concerned with a monopoly on what they put out. They just want a monopoly on our attention. The size and structure of the industry’s corporations is not sustainable if they have to compete with some random dude from Stockholm for our hearts and minds. For a huge movie, album, book, or game, the competition isn’t piracy; it’s a small movie, album, book, or game.

Unfortunately for the copyright industry, they can’t make it illegal to release your work independently. That would probably require a complete repeal of free speech, which would make for an insanely expensive lobbying campaign. What they can do is cripple the Internet.

SOPA was criticized because it would do just that. YouTube, Facebook, Wikipedia, comments threads on blogs, all would be crippled or unable to operate due to the new law. Maybe this wasn’t an accident. Without forums and social networks to tell you about the hot new indie band/film/game, and without cheap and easy ways to distribute it, there’s no more competition to the copyright industry. Underground culture remains underground, only breaking out into the mainstream if the copyright industry buys it and allows it to.

So is the copyright industry full of diabolical evil geniuses rather than blabbering morons? Not necessarily. It’s possible that they don’t actually think any of what I’ve just said, and they seriously believe that piracy is going to kill them. Maybe they’re pursuing a smart business strategy completely by accident. Because destroying the free and open Internet is a very, very smart strategy to save the copyright industry.

January 6, 2013

Banana Republic Justice: Behind The Scenes Of The Pirate Bay Trial

Corruption: Process of law failed on so many accounts in the trial against the two operators of The Pirate Bay, its media spokesperson, and a fourth unrelated person that it’s hard to get a bird’s-eye view. This trial was characterized by first deciding that the operations were criminal, then finding somebody to punish, and finally trying to determine a criminal act they could be held accountable to. In any civilized country where process of law works, the exact reverse order is followed.

First, we know that the United States ordered the shutdown and trial of The Pirate Bay. This was confirmed by Swedish Public Television, showing how the then-Swedish Minister of Justice Thomas Bodström had been in contact with the US State Department through intermediaries.

Then, in the raid on May 31, 2006, the Police emptied an entire server hall and didn’t just seize The Pirate Bay. In an apparent deliberate attempt to create a public fear of association, almost 200 mom-and-pop stores got their servers seized in collateral damage. The copyright lobby’s reps were quoted as saying, “you should be careful with where you place your servers”. (Later, some constitutionally protected servers – registered news publications – were actually given back, but not before a judge had intervened hard. Other servers, such as The Pirate Bureau’s discussion forum, remained in seizure.)

To further create a fear of association, the police harassed the site’s legal counsel by forcibly sampling and registering their DNA for any and all future use.

The lead investigator with the Police for the case, Jim Keyzer, was hired by Warner Brothers, one of the plaintiffs, before finishing the investigation and while still on notice with the Police, and was already hired by Warner when conducting the hearings and wrapping up the investigation. This is a textbook bribe, which is why you will find many Swedish blogs referring to “the bribed policeman Jim Keyzer” (den mutade polisen Jim Keyzer). The Swedish then-Minister of Justice Beatrice Ask commented on the case: “it’s positive that our policemen are hired from outside the Police Authority. That indicates they’re attractive”.

The presiding judge in the District Court, Tomas Norström, picked the case to himself. This is not supposed to be possible, but he argued that his court department (which specialized in copyright monopoly cases) should have the case, and he just happened to be the only available judge there. Norström was a signed-up member in the Swedish Association For Copyright, just like all the plaintiffs were, as well as a board member in The Swedish Association for Protection of Intellectual Property, giving him a political as well as a possible social interest in the outcome of the case and making him textbook corrupt. (This is why you see a lot of Swedish blogs discuss “the corrupt judge Tomas Norström”.)

In the investigation, the two operators of The Pirate Bay were initially indicted. For some reason, its media spokesperson Peter Sunde, which had openly talked back to the copyright industry, was indicted too despite having done nothing but talking, and a fourth completely unrelated person was indicted more or less because he was rich and could be ruined as a warning to others, to create yet more fear of association. (This would not be the official reason, but the obvious reason to everybody else.)

During the trial, the defense pointed out that it had not been proven that any crime had been committed at all which the four were on trial for aiding and abetting. (Sharing culture is fully legal in many countries, and the prosecution hadn’t cared to show that a criminal act had been committed – only that sharing of culture had happened somewhere, but not that it was illegal in that location. If it had happened in Spain at the time, for instance, it would have been fully legal.) The prosecution agreed with the fact that no crime had been proven to have been committed in the first place, and then, that quite crucial fact magically vanished from the end verdict, where they were found guilty of aiding and abetting that non-shown crime.

And the media spokesperson, Peter Sunde? He was convicted for part in operating The Pirate Bay based on a load balancer he had placed in a server rack, a box that had not had a single wire attached to it in The Pirate Bay’s server hall, and which was configured for something completely different than The Pirate Bay. Documentation of this configuration had gone completely missing from the investigation where everything else was meticulously documented.

The judges in the Appeals Court denied a retrial in the District Court based on the charges of a biased judge. Those judges had been part of the same pro-copyright political organization as Tomas Norström, and didn’t see any bias.

Nobody paid much attention to the appeals trial in the Appeals Court, as the landmark case was expected to go to the Supreme Court. It was the middle act in a three-act play. Still, in the Appeals Court, not one but two of the judges had a background from the same kind of pro-copyright lobby organizations as the District Court’s Norström. They confirmed the District Court’s verdict of guilty of aiding and abetting the crime that was never shown to have taken place.

Then, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case. At that point, the four people went into exile.

This is just a small subset of the things that are… remarkable… about the trial against the two operators of The Pirate Bay, its media spokesperson, and a fourth unrelated person.

Sweden has a justice system unworthy of a banana republic. When the establishment is threatened, or when the US of A calls for Sweden to jump, all rights and due process go out the window.

January 5, 2013

The Copyright Monopoly Stands In Opposition To Freedoms Of Contract

Copyright Monopoly: In our series highlighting misconceptions about the copyright monopoly, we’re arrived at comparing them to contract rights. Several people who defend the monopoly from a libertarian standpoint claim that a sale can be put under any conditions, otherwise known as freedoms of contract. The copyright monopoly stands in opposition to this freedom.

We have previously examined how the copyright monopoly stands in . This doesn’t, in and of itself, invalidate a mechanism where people transfer exclusive rights (“monopoly rights”) by contract – it just highlights that the copyright monopoly cannot be defended from a standpoint of defending property rights, as the copyright monopoly limits property rights and stands in direct opposition to them.

Once we go beyond property rights and look at the right to transfer exclusive rights in general, we can talk more easily about the right to contract and how it would fit with the exclusive rights we know as the copyright monopoly.

Often enough, the argument is heard that the copyright monopoly is an extension of, or based on, the right to sign contracts voluntarily. It is argued that you can transfer a right (a property right, a monopoly right, or other form of right) under any conditions that you and the buyer agrees on, and that this would be part of the freedoms of contracting.

In other words, “if you don’t agree with the copyright monopoly terms – that is, the terms of sale – don’t buy the DVD.”

But it this really what the copyright monopoly is? Freedom to contract? Let’s look at what happens when Alice sells a DVD to Bob (possibly through an intermediary that, for all intents and purposes, mediates the contract), and the sale includes a written condition to not share the bitpattern on the DVD with anyone else, which Bob even reads, understands, contemplates, and signs.

In this case, Bob would be bound by contract to not share that bitpattern. So far, so good. But let’s assume he does anyway. He shares the bitpattern with Carol, who manufactures a copy of the DVD using her own parts and labor.

In this, Bob would be in breach of contract with Alice. But what about Carol’s copy? Carol has signed no contract with Alice whatsoever, and contracts aren’t contagious in the sense that they follow the original object, concept, idea, or pattern; they require voluntary acceptance from an individual, which Carol has not given. Carol has signed no contract, neither with Bob nor with Alice.

Thus, Carol would not be bound by the original contract in the slightest on a functioning free market, regardless of Bob’s breach, and she would be free to share the bitpattern of her own copy of the DVD as much as she pleased with David, Erik, Fiona, and Gia, who could all manufacture their own copies from the bitpattern that Carol shared, without any breach of contract having taken place.

But the copyright monopoly prohibits this. Carol would be in breach of the copyright monopoly, which is a highly unnatural construction on a free market. Contracts don’t work this way at all, and therefore, we have demonstrated clearly in this example that the copyright monopoly cannot possibly be seen as an extension of the freedom to sign contracts.

But it goes beyond that observation. The copyright monopoly limits Carol’s rights to sign contracts in her turn regarding her property that she manufactured with her own parts and labor – the DVD with the bitpattern: it limits her ability to sign contracts with David, Erik, Fiona, and Gia regarding this piece of property, should she desire to do so. For example, with the copyright monopoly in place, she cannot even legally execute one of the simplest forms of transaction – a transfer of property. She can’t make additional copies of her own property and sell them, or even give them away without any terms whatsoever.

Thus, the copyright monopoly doesn’t just not follow from the freedoms of contract. The copyright monopoly stands in direct opposition to the freedoms of contract.

Therefore, the monopoly cannot be defended from the perspective of the right to apply any terms to a voluntary sale. The monopoly limits such rights.

January 4, 2013

Two Swedes Renditioned To The US, Possibly To Death Penalty, In Secrecy And Without Lawyers’ Knowledge

Process of Law – Henrik Alexandersson: Mid-November, two Swedish citizens with Somali origins were renditioned from Djibouti to a prison in the United States of America.

According to the US, they are hardened terrorists. According to other people, they tried to leave the terrorist-branded organization al-Shabaab. What’s true there is unclear. But that’s not the point that makes us interested in the story.

An representative of United States Intelligence Services is reported to have told the two Swedes that “We’re waiting for permission from Swedish authorities to take you to the United States”. This is something that the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs first didn’t want to be associated with, and later declines any and all forms of comment.

Here, we have a natural and special interest, as the two men are Swedish citizens. Are they suspected of committing an act which carries criminal penalties in Sweden – and if so, should they not be indicted and prosecuted in Sweden? Or has the Swedish government given the USA a carte blanche to “take care of” two Swedish citizens in the name of the war on terror – and if so, on what grounds? (Further, the suspicions concern acts committed in Somalia, where the US doesn’t have jurisdiction.)

Suspicions of terror or not – the process of law must be respected, and international law followed. The government has no right to throw people into dark dungeons without a proper trial. We have a right to demand some form of damn order here.

This affair has a distinct image of not having respected due process. This image is further strengthened by the fact that the two Swedes’ lawyers and relatives were kept in the dark for several weeks about what had already happened.

If Sweden has agreed to rendition two people – Swedish citizens or not – to the United States of America within the context of what’s known as extraordinary renditions, this affair goes far beyond the questions about the formal due process. In such a case, it’s necessary to ask how much the Swedish governments’ promises are worth, when they promise to not extradite people to countries where they risk torture or death. This is a question that’s current and relevant in other cases, for example, regarding the Wikileaks founder Julian Assange.

This affair smells really bad…

Read More: Washington Post [in English], Svenska Dagbladet [in Swedish].

UPDATE: The lawyer of the two Swedes was informed of the rendition on December 7, about three weeks after the fact. When the lawyer was informed, and only then, were relatives informed. This has eerie similarities with banana-republic “disappearances”.

This article was originally published in Swedish on Hax’ blog. Translated into English by Rick Falkvinge.

January 3, 2013

Traffic Numbers For 2012 For Falkvinge & Co. On Infopolicy

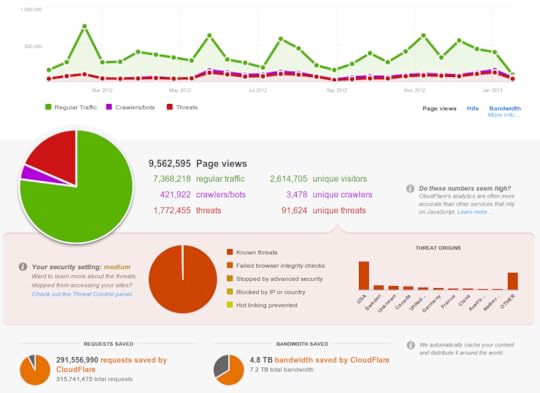

Metaposts: 2012 was a good year for this site. We count about nine million visits in total from about 2.7 million unique visitors. That’s the population of one Nevada or Utah, two Estonias, or eight and a half Icelands having taken part of the ideas here at least once in the last year. Excellent!

Spreading an understanding of information policy is paramount, and we’re working hard on it. Writing well enough to reach almost three million people in the last year is one of the best conceivable rewards. And still, we keep growing and learning how to write better, to be continuously read by yet more people. As of the New Year, Falkvinge & Co. on Infopolicy has a full 70 contributors – mostly the occasional guest author and a skilled crew of volunteer translators to ten other languages.

315 million HTTP requests were served with just over seven terabytes of data over the year.

Traffic data for 2012. Don’t worry so much about “threats”, I’ve learned that’s usually just regular visitors coming in over TOR and other anonymizers. For this site, anyway.

Happy new year, and may the world see better information policy in 2013!

December 30, 2012

The Copyright Monopoly Is A Legal Featherweight Compared To Property Rights

Copyright Monopoly: In our series of misconceptions about the copyright monopoly, some people defending the monopoly keep asserting that it carries the same legal weight as property rights. This is not so much misguided, as it is merely factually wrong from every angle.

When faced with the fact that the copyright monopoly is a limitation of property rights, some defenders of the monopoly claim that property rights and the copyright monopoly “carry equal legal weight anyway”, in an attempt to downplay that argument’s importance in the debate about the copyright monopoly’s legitimacy. Their claim calls for fact checking and further scrutiny.

When comparing the copyright monopoly to the property rights that it limits, we can go to the constitution of many countries to compare their respective weights. Starting with the US Constitution, we can readily observe that property rights are a long-running tradition of the British Common Law, and find several passages that limit Congress’ ability to curtail those property rights by law.

One of the most-quoted of these passages may be in the US Bill of Rights, in the Fifth Amendment: “…nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation”.

In contrast to safeguarding property rights, the US Constitution does not require the Congress to have any copyright monopoly at all on the law books, but merely grants Congress the power to enact such a monopoly (“exclusive rights”) if it finds that doing so promotes the development of culture and knowledge.

We find this passage in Chapter 8 of the US Constitution: “[Congress has the right] …to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

The right to create the monopoly – but not the obligation.

So, property rights are constitutionally safeguarded, whereas the copyright monopoly may exist as a law or it may not, as Congress desires from day to day. That is obviously not the same legal weight. The copyright monopoly is a featherweight by comparison.

Other countries show the same pattern. Let’s look at Sweden, where property rights are similarly protected in the constitution.

In Sweden’s Regeringsformen constitution, chapter 2 para 15, we find that “…the property of everyone shall be safe against expropriation to public or private interests, except when needed to accommodate urgent public interests”, in which case full compensation blah blah. Pretty much a mirror image of the US Bill of Rights. And what do we find about the copyright monopoly? It is indeed in the constitution, in the very next paragraph:

Chapter 2, para 16: “Authors, photographers, and artists have rights to their works that are determined by ordinary law” [as decided by Parliament].

Thus, we observe the same difference in legal weight here – the property rights are heavily safeguarded in the constitution, with no rights for Parliament to jeopardize them, whereas the copyright monopoly can be abolished, changed radically, or turned into ice cream tomorrow if the Swedish Parliament so desires.

That is obviously not the same legal weight. The copyright monopoly is a featherweight by comparison.

While the copyright industry has been trying to portray the copyright monopoly as “property” in order to legitimize their lucrative monopoly, the copyright monopoly is a governmentally-sanctioned private monopoly that stands in direct opposition to property rights. And as this article has shown, the monopoly is nowhere near the legal weight of the property rights that it limits.

December 25, 2012

Why Conservatives And Libertarians Should Be Sceptical Of The Copyright Monopoly

Copyright Monopoly – Christian Engström: The book Copyright Unbalanced – From Incentive to Excess appears to be very interesting.

From the ad for the book:

Conservatives and libertarians, who are naturally suspicious of big government, should be skeptical of an ever-expanding copyright system. They should also be skeptical of the recent trend toward criminal prosecution of even minor copyright infringements, of the growing use of civil asset forfeiture in copyright enforcement, and of attempts to regulate the Internet and electronics in the name of piracy eradication.

Copyright Unbalanced is not a moral case for or against copyright; it is a pragmatic look at the excesses of the present copyright regime and of proposals to expand it further. It is a call for reform—to roll back the expansions and reinstate the limits that the Constitution’s framers placed on copyright.

I have read the first chapter which is available freely, and that chapter made a lot of sense. It starts with a discussion of property rights:

Traditional property rights, often associated with John Locke’s theory of rights, include rights to real property, personal property, and property in one’s self. The legitimacy of these rights is not just uncontroversial among libertarians and conservatives, it is foundational to their respective political ideologies.

Traditional property rights predate the Constitution, and their contours were developed over centuries in customary law and the iterative and evolutionary process that is the common law. The main text of the Constitution doesn’t even mention a right to property, signaling that the Framers took it for granted.

So far, so good. Although the author Jerry Brito does not mention it, he could have added that property rights are pretty much uncontroversial not only among conservatives and libertarians, but in most other political camps as well.

He then continues (writing from a US perspective, where copyright is mentioned in the Constitution):

Copyright is a very different animal. In contrast to traditional property, copyright was created by the Constitution; it did not exist in the common law. Without the Constitution’s copyright clause, there would be no preexisting right in creative works. What’s more, the copyright clause does not recognize an inalienable right to copyright, but instead merely grants to Congress the power to establish copyrights. Copyright therefore stands in contrast to traditional property in that the legislature has complete discretion whether to grant the right or not.

The concept of property and basic property law developed spontaneously long before the US Constitution was drafted, whereas copyright is a system that was invented by legislators.

This does not in itself necessarily mean that copyright is wrong or evil, but it does mean that the legislators who built the system will had to base it on guesses rather than knowledge that had evolved over time. How can we be sure that the legislators (Congress, in the US case) guessed right?

Without copyright, there would still be songs written and movies made. Congress just thinks there wouldn’t be enough. So, it offers a subsidy in the form of copyright protection to incentivize more creative output. … How does Congress know we wouldn’t have “enough” creative works without copyright? And assuming it knows that, how does it know the right amount of incentive to offer?

The answer is of course that the legislators don’t know for sure what is the ”right” amount of copyright, and there are strong indications that the strengthening of copyright and copyright enforcement that has taken place for the last decade has gone much further than any reasonable arguments could support.

The author gives several examples of excesses in recent legislation, and notes that there is a mismatch between copyright legislation and the general public’s perception of what would be fair and reasonable. He makes an interesting comparison:

Donald Harris has compared the current state of affairs to the Prohibition era because law has outpaced societal norms. There might also be a comparison to the drug war.

He concludes:

Conservatives and libertarians, who are naturally suspicious of big government, should be skeptical of an ever-expanding copyright system. Congress today routinely shifts the copyright balance in only one direction: away from public access and freedom, and toward greater and deeper privileges for organized intellectual property [sic] interests. If we take economics and public choice seriously, then we should be concerned.

There is no incompatibility between respect for property and wariness of a radically unbalanced copyright system. Conservative politicians are beginning to understand this.

Speaking from a European perspective, I unfortunately can’t say that I have seen many signs in the European parliament that the conservative politicians there are beginning to understand the issue. But if it is indeed true that there is intellectual movement among conservative politicians in the US, maybe some of that will spill over to Europe in due course.

That would be very welcome.

Read the chapter Why Conservatives and Libertarians Should Be Skeptical of Congress’s Copyright Regime.

This article originally appeared at MEP Christian Engström’s blog.

December 22, 2012

The Copyright Monopoly Stands In Direct Opposition To Property Rights

Copyright Monopoly: A lot of today’s bad policy stems from the misconception that the copyright monopoly is related to property rights, an illusion peddled by the copyright industry’s own powerful lobby. The idea that the copyright monopoly would be a property right doesn’t just lack factual basis, but it is 180 degrees and one hundred per cent wrong, factually wrong. The copyright monopoly stands in direct opposition to property rights.

The copyright monopoly is a governmentally-sanctioned private monopoly. No liberal, socialist, green, capitalist, or conservative can defend those constructions from their ideology; this construction only fits corporativist and protectionist ideologies.

Allow us to illustrate with a tangible example: assume that we buy a copy of a chair. We say “a copy”, as it is automatically made from a master in the form of a digital blueprint in some sort of plant; colloquially, we’ve bought “a chair” at IKEA. We own this copy of the chair, we have our receipt here in hand. This physical object, in all its aspects, is our property. We are allowed to do a number of things with this copy of the chair:

We can take the chair apart, and use pieces of it for new projects that we make in our workshop.

We can look at the underlying pattern to examine how the chair is built, make an identical copy, and sell it.

We can put out our chair on the porch and use it there, and we can charge our neighbors to use it if we like.

All of this is typical for property. These are typical actions we can all take with our property without anybody raising an eyebrow.

In contrast, assume that we buy a copy of a movie. We say “a copy” as the disc with the movie is automatically made from a master in the form of a digital blueprint in some sort of plant; colloquially, We’ve bought “a movie” at the gas station. We own this copy of the movie, we have our receipt here. This physical object, in all its aspects, is our property. Yet, we are not legally allowed to do certain things with this copy of the movie:

We are not legally allowed to remix the movie that we own and use parts of it for new projects.

We are not legally allowed to examine the underlying bitpattern and make an identical copy on a different storage medium which is the property of somebody else, nor are we allowed to sell a copy we have produced with our own property and labor.

We may not use our movie on the porch, and may not charge our neighbors to use it.

Somebody’s monopoly overrides our property rights and makes it illegal to use our legal property and exercise our normal property rights using our own work and labor.

The copyright monopoly is a governmentally-sanctioned private monopoly on certain forms of duplication and performance. It doesn’t just stand in opposition to property rights, but to free trade as well.

(Some people would argue that even property as such is a governmentally-sanctioned private monopoly, in order to downplay the fact that the copyright monopoly stands in opposition to property rights, but that would not be what we mean by “property” and “monopoly” as concepts. If I own an umbrella, I control that umbrella. If I have a monopoly on umbrellas, I get to control everybody else’s umbrella too, and get to call on the government to have that enforced.)

It is quite possible to argue for the copyright monopoly from a purely utilitarian, protectionist, or mercantilist perspective, but not from a “property is good” perspective: you will end up in the exact opposite conclusion. By extension, since we know that property rights are good for trade, we also deduce that the copyright monopoly is bad for trade and competition. This comes as no surprise, seeing how the copyright industry has been fighting tooth and nail against the more-efficient industries that would otherwise already have replaced them.

December 21, 2012

Good News: US Congressman Is Against DRMing 3D Printers To Stop Them From Making Guns

Activism – Zacqary Adam Green: Last week, US Congressman Steve Israel made some unsettling comments about 3D printers, and how they can be used to make guns. Fearing another luddite legislator, I decided to do something crazy: actually talk to him. Turns out, we don’t have that much to be afraid of.

Some background: the congressman was speaking at an airport security terminal, discussing the threat of 3D-printed plastic guns that wouldn’t set off a metal detector. He was using this to drum up support for a renewal of the Undetectable Firearms Act, which bans any kind of gun that won’t make the security devices go bleep-bleep if you bring them into an airport. Now, this is a fairly silly law; as far as I know there’s no evidence that a working gun without any metallic parts has ever been built, nor has a feasible design been proposed. But at least it’s a benign dumb law.

My concern was that the next step would be a crackdown on 3D printers themselves, using some sort of DRM-like method to try and prevent them from printing gun parts. It wouldn’t, of course, and only succeed at causing a whole lot of other problems (as DRM is wont to do).

Conveniently, I live in Steve Israel’s district, giving me priority access to discuss the issues with him. In the end, I was only able to schedule a talk with one of his advisors — not the man himself — but talking to congressional staffers tends to be equivalent to speaking with the legislator whom they serve. The goal of my talk: convince the congressman that the threat of more guns was not worth crippling 3D printers with a Digital Restriction Mechanism.

Luckily, I seemed to mostly be preaching to the choir. Turns out his staff has read a great deal of the backlash on the Internet, and they’re aware that restricting 3D printers themselves would cripple innovation. The congressman doesn’t want to DRM printers, and it doesn’t look like he’d be for it in the future. All he wants to do is make it illegal to build a working firearm from home-printed parts.

Now, this isn’t a particularly good idea either. Criminals won’t listen. The law will only inconvenience law-abiding gun owners who want to make their own firearms instead of buying from a manufacturer. Banning 3D-printed guns will do less to protect the public than it will to protect Smith & Wesson from competition. So that would suck. But at least it wouldn’t cripple the entire technology.

What the congressman’s staff hadn’t considered was the future possibility of literally every large company that manufactures anything at all lobbying for DRM to kill competition. I predicted a future scenario of home 3D printers restricted to only print things from, say, the Apple Object Store — with a cumbersome approval process that favored established manufacturers. It would be illegal to get around this restriction because, well, guns! I dropped a reference to the copyright industry’s history of scapegoating child porn to make DRM and censorship seem palatable; if they’d exploit child abuse, I argued, why wouldn’t the manufacturing industry exploit gun violence?

Hopefully, Congressman Israel is now prepared to take this crap with a grain of salt, when it inevitably comes up. Assuming the congressman and his staffers are on the same wavelength, we now have an ally in the US House of Representatives who’ll fight against crippling DRM on 3D printers. And maybe someone with a more realistic approach to gun control too; the staffer seemed receptive to the idea that gun control won’t be possible in a decade or two.

Unfortunately, this means I just lobbied Congress. That makes me me a lobbyist. I need to go take a shower now.

Rick Falkvinge's Blog

- Rick Falkvinge's profile

- 17 followers