Sophia Al-Maria's Blog

March 11, 2018

Fog of Fogs, Blog of Blogs

It’s been almost a year since I’ve updated this blog and over a decade since I started it. So for old time’s sake and an OCD desire to graft the missing pieces together for myself in some kinda continuum – here are a few highlights in a year that seemed to slip right by me in a fog of fogs. So this is a blog of unwritten blogs. I can’t remember what I did most days, let alone most years so this is a feat.

MOTHERSHIP on Random Acts Channel 4, UK

Mothership is a haunting vignette that straddles the line between documentary and fantasy. A tiny drama of cosmic proportions performed in a sinkhole in the desert where a new born earthling receives a shadow visitor: time – the terror of all creatures

2. The Gaze of SFW … on printer paper.

e[image error]

The text of The Gaze of SFW was printed endlessly on a dot-matrix printer at The Mistake Room in Los Angeles in a show called Analogue Currency which looked great but I didn’t get to see. Happy seeing the Arabic Sign Language images printed up as well. Found those a decade ago on a CD rom my aunt had while learning to teach her deaf and hard of hearing students. They’ve made the rounds since and I wish I could find who took the original photos. Thanks very much to Hanna Girma for making that happen.

3. New vid for Fatima Al-Qadiri’s “Spiral” featuring Bobo Secret

[image error]

4. The Magical State in Paratoxic Paradoxes and the Lima International Film Festival (Experimental)

[image error]

5. My first commissioned script The Medusa looked like it was going to happen. But then didn’t. (x paws for 2018)

[image error]

April 2, 2017

EVERYTHING MUST GO IS GOING GOING GONE

My show for The Third Line Gallery is now closed. I post this now after the fact for my own reference. Some coverage here, here and here. In case you’re reading – I especially want to thank you Sybel Vazquez for wrangling me and Misha Michael as chief producer on this version of The Litany. And everyone at The Third Line especially Sunny Rahbar for being my go-to-girl for the impractical schemes what I dream. Also Omar Kholeif who wrote the text for the catalogue. ❤

Goodnight to the Gone Gone Gone.

[image error]

November 18, 2016

The Limerent Object @ Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève

Dear fragile-posterity-for-which-this-blog-is-maintained,

I’m pasting below the description of a new video piece called The Limerent Object you can visit should you be in Geneva soon.

The installation is floor to ceiling in a long dark room with brick that reflects the blue colour. Very cave. You can find an interview discussing the piece in depth with JOÃO LAIA here. And in FRENCH here.

Someone tell me, am I more pretentious in French?

I would like to thank the below individuals from the bottom of my alien vital organs.

As you can see, the editor is a total egomaniac. But everyone else is a dream to work with!

But seriously. Thanks to the talented Léo Parmentier. As ever Anna Lena Vaney pulled it off at short notice with minimal resources. Sahra Motalebi’s sound work is strange and horrifying and stands alone. Éponine Momenceau & her camera team captured Francois Chaignaud’s performance with incredible grace. And a very, very special thanks to Meiling Cooper for applying the liquid mercury to the fleshy flesh. We got in trouble at the studio for destroying their lovely blank space with so much silver effluvia.

Here are some BTS shots of the aftermath.

And also I would like to thank THE Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2016, THE Fonds d’Art Contemporain de la Ville (FMAC) and the Fonds d’Art Contemporain du Canton de Genève (FCAC), Faena Art, In Between Art Film and HEAD – Genève.

“The Limerent Object is a call-and-response across deep time between the last living earthling and their extra-terrestrial anticedent. Mixing myths of a panspermic genesis and a Holocene apocalypse, The Limerent Object juxtaposes petroglyphs and porn, an alien queen and a dying human, a voice and the silence to evoke a love story that transcends the desert of millennia. This new work stems from the artist’s anxiety and fear for the future and the result is a poetic panegyric to the planet earth and we who people it.”

X

August 10, 2016

BLACKFRIDAYALLDAYEVERYDAY

So. I’ve been working on this show that has been ALL consuming the past few months. It’s been BLACKFRIDAYALLDAYEVERYDAY.

The show opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City on July 25th.

There’s info about it here. And you can read the curator Christopher Lew’s great essay about it here. There’s more on CNN. New Scientist. New York Times. And I add sheepishly, in the August 2016 US Vogue. As well as upcoming pieces in Dazed + Confused, Art Forum, Mousse and Kaleidoscope.

Perhaps most amusing so far is this subedit nightmare and FUBAR comments section in The Guardian. But it’s actually a really thoughtful piece I appreciate greatly by David Shariatmadari.

Anyway. It’s open until October 31st and over its three month lifespan much of the installation will die (hopefully not too painfully) so go see it sooner than later if you want to see all of the 113 unique videos before they ‘pass on’.

I wanted to use this post to thank by name all the geniuses and genies who made the show possible because as you may have noticed, kunstwelt rarely gives artists wallspace (or any space really) to do that.

Zone out if you hate long awards speeches but zoom in if you want to know how this behemoth of a thing was made.

Up front I want to thank the Whitney Museum, its incredible staff and Christopher Y. Lew for not only inviting me but hosting me in his mother’s future flat!

Vitally, my queen Anna Lena Vaney of Anna Lena Films for midwifing this project from start to finish. She has been a constant support for many years now and we finally got to make a film together!❤

Qatar Museums and specifically H.E. Sheikha Mayassa for making the main film Black Friday possible financially.

To Justin Kramer and everyone at The Film House in Qatar for being so game and flexible to do something weird in a sea of corporate. To Moon for the swoon. And Ashiq, stay golden. The shoot saw us spend every night in a mall, every day on the sweltering road, consume way too much McDonalds plus someone climbed into a hyena enclosure and we all survived!

To the ever enthusiastic and encouraging Asad Raza for bringing me to the Villa Empain in BXL to stew in the rushes and gestate the work. The vital organs were formed there. I want to come back to that grey deco death cake.

While on the subject of Brussels I’d like to thank my Premiere Pro prince – the peerless Léo Parmentier who worked editing in tandem with me for almost a month in and out of public and came to London to finish the 113 videos and heroically stepped in as post-production supervisor when things got sticky and made me laugh while doing it.

So also

November 30, 2015

PALAVER PALAVER PALAVER

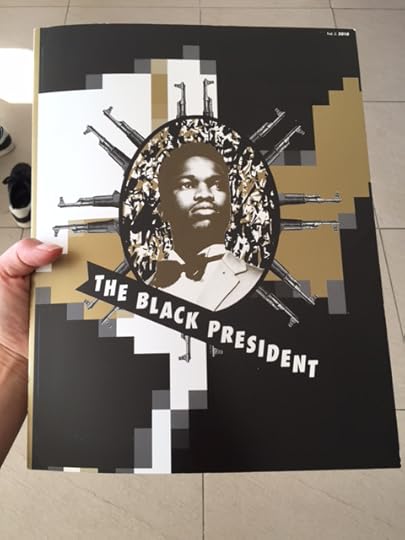

There was a ripe yield down at the Second-hand Books & Bric-a-Brac yesterday. In amongst the tarnished silver and cracked figurines was this book.

It’s a collection of columns from the Zimbabwe Standard called Palaver Finish by Chenjerai Hove who died in exile in Stavanger only a few months ago.

It was hard to get a handle on the title essay which is written in what’s for me – unparsable pidgin. But I found this clue to its meaning in a book by Moradewun Adejunmobi, “palaver,” connotes “contentious discussion”.

And that may be what I’m about to step into without knowing it.

It appears some of his contemporaries like Dambudzo Marechera thought Hove’s work was too ‘nativist’ but I’ve asked around and although Marechera was tragic and beloved and brilliant – it also seems like he shouldn’t have been dragging anyone through the dirt. At least Hove made women the central heroes of his stories while Marechera was straight up called a misogynist by the person writing the introduction to the Penguin edition of Mindblast.

I really chimed with Hove’s thinking. It’s foundational and real and accessible and clear. And I admire that as much as glorious, violent explosions of literary fireworks Marechera was known for.

On a more general note: in the month I’ve been in South Africa – I feel very strongly that Arab artists and writers should pay more attention to what’s going on and has gone down in Africa.

Because it’s relevant. Period.

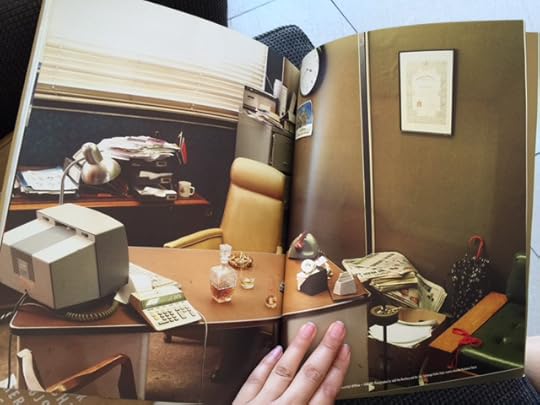

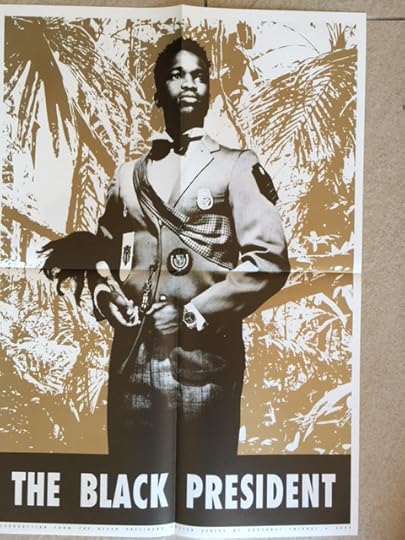

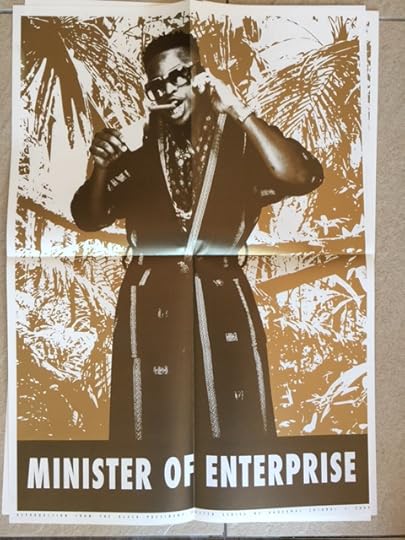

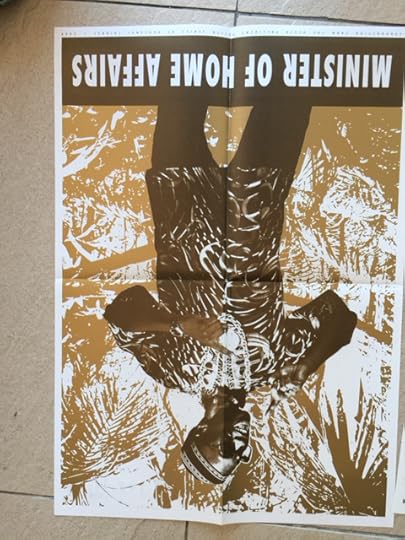

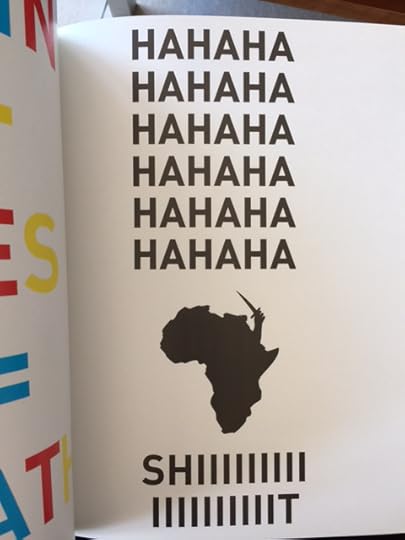

To prove this I am including some snaps out of a 2010 copy of Lines Magazine edited by Kudzanai Chuirai. His work is a perfect example of the ‘relevant’ mentioned above. Example: the below piece is called “The Presidential Office 16h30”. Now, the collective GCC mounted a very similar piece at MOMA PS1 a few years ago and I know for a fact (I was a part of GCC at the time) that we didn’t know Chuirai’s work. But we were treading in exactly the same territory – right down to the portraits as self-aggrandising cultural ministers.

Anyway, enjoy the friction of Chuirai’s hyper-irony and Hove’s ultra-earnestness rubbing up against each other. Maybe it will light something for you as it has me.

Culture as Censorship

Excerpted from Palaver Finish

By Chengerai Hove

I was born under this blue sky, in the year of the railway line, somewhere under the shadows of the Zvishavane hills, in a mud hut, with no nurse nearby. I only came to know about nurses in primary school: the nurse was the one with sharp needles for anti-primary school: the nurse was the one with sharp needles for anti-this and anti-that. We did not have to know what the inoculations were for. They were part of life, and it went on from sunrise to sunset and from sunset to sunrise.

Our world is measured in many ways: some measure it in sunsets, some in clock-time, some in moons. But we measure time by events. If when you were born nothing else happened, then your birth might be a difficult yardstick. A good birth lies in relation to there, me and my brothers and cousins, who were born around that time, to the railway line, to check the dates of our births.

To talk literacy and illiteracy is irrelevant. Our parents had their own multi-literacy in many things we did not understand. We were illiterate, young and fresh. Many things still to know and discover, including the kick of a donkey, his mark still visible on my face. (As it happens, I was nearly buried, having been unconscious for longer than the villagers could accept. I’m only alive, thanks to my mother who persuaded them to allow me another day.)

As we grew up, we were told to be wry of a certain two men who always wanted to play with us and offered us sweets. Only now do we realize that they were gay. My relatives would turn in their graves at the thought. To write about those characters is to let slip the ugly face of the village. Every village wants to be portrayed as beautiful, a place into which you were lucky o be born. Thus, cultural pride becomes cultural censorship.

What, after all, is censorship? Is it not the control of local ideas to stop tem spreading from the private parts of the village to the public parts of the country? And what is culture? Is it not the things we tell ourselves, the things we pretend to ourselves, about the ways we live and die. Culture is the way we eat, or do not eat, the way we die or do not want to die, the way we talk to the dead to allow for communication between the living and the dead. Even the way we play represents some form of our culture.

But the masks change with time, the ways we eat change with time, and the voices which we name ourselves change with time. Culture does not exist in a museum. Tradition can.

And the story goes on.

How many of us can write an erotic piece?

No, we would shy away from the public glare. Can we write of the body of a woman or of a man, in all its sexuality? We cannot do so because people, in this part of the world, will say, this does not happen in our culture. Isn’t culture sometimes a lie with which we all concur? Imagine a woman, in these lands, writing poetry abut the love she has for a man. She would be in such trouble that she would wish she had never gone to school or learned to write.

An Indian scholar described power as ‘a desolating pestilence’, meaning that power can be an instrument of censorship. Power is a cultural tool and the wy people relate to it is crucial for the development of the imagination, the mind, the heart, and the soul.

In Zimbabwe today, power is used as violence. Violence has become part of our culture. Violence opposes freedom but the human mind and heart need freedom if they are to bloom.

Ask George Mujajati about it. He is the most tortured writer in this country at the moment. He cannot sleep in peace in his own house. And the violence against him means he is supposed to fall silent, to disappear as it were. When local politicians announce death to those who do not support the ruling party, this is sad news for the imagination.

Religion can also be used as an instrument of censorship. The religious sometimes have the audacity to think that everyone must see the world as they see it themselves. Anybody who does not share their beliefs is considered a heathen, a devil, and thus the literary imagination is controlled. For, censorship has to do with controlling the imaginations and products of other people’s imagination in an attempt to make the world uniform, mono-cultural, and mono-everything else.

We can talk of language as censorship because it is an instrument of life. Language tends to be harnessed by those who think they own the social imagination. Language is culture and culture Is communication. Silence is not culture. Without communication, all the doors of human existence and human exchange are closed and locked, as Mujajati says in The Sun Will Rise Again. ‘Culture is an instrument of aspiration and dream. Within it, the dreams of the ordinary person may live or die.’

Violence inflected on people can mean the death of creativity.

November 8, 2015

Cry of the Chicken Nugget دعاء التشيكن ناجت

How do you feel about this statement?

“An Arab is a person whose mother tongue is Arabic.”- Article 10, 1947 Ba’ath Constitution

I’m not one of these people who can pick up languages like shells on a seashore.

I have to be drowning just to work my way up to a fluent float and even then I barely keep my nose above the water.

If I’m not fully ‘immersed’? Well, the words just dry up in the sun. Evaporate on my tongue. And in some cases, leave an unpleasant aftertaste.

As an American, I imagine I probably modulate louder than I should in English (It’s hard to tell from inside your own head). And yet as an Arab – in Arabic – I’m usually ‘in the back on mute’.

There’s a pre-vocalised stammer when I use the father tongue, it’s like there’s something that jams whatever cortex controls speech and so opening my mouth releases a whole shoal of fears and insecurities and existential wobbles that I can’t really articulate.

But fuck it – Ima try.

Writing in English is now my job – and over the years – Arabic has become almost vestigial. It’s like a ghost limb that’s withered up from disuse. I retain the ability to write and read (and type 50 wpm blind) and yet the netting of this most beautiful alphabet is like a sieve that meaning just drains right tf out of.

I used to want to sing in Arabic but I’ve struggled to work up the guts to even speak.

99% of the time if a stranger in Egypt, Lebanon or Syria (the only places in the Arab world I have travelled without the visual signifier of my Abaya) ever asked where I was from they invariably would guess Morocco (which I guess basically meant I didn’t make sense and sounded crazy). When I went to Morocco – that’s another story. My family in the Gulf used to call me ‘the Egyptian’. Old friends say my accent has now accrued the melted limey runoff of a person who’s been living in the UK for too long. But then again, I’ve had a few non-partisan people and tutors tell me my Arabic is better than I think it is – I just lack the confidence to speak. Whatever the case – my language, like me, is a mess. And at the end of the day, what language are you reading this in?

To clarify the title of this post Cry of the Curlew by Taha Hussein is the first novel I ever attempted to read in Arabic (and never finished I should add) and Chicken Nugget is the nickname for a generational cohort in the Gulf which I don’t identify as but maybe should. Like re-constituted chicken bits – a ‘Chicken Nugget’ is made from a lingual slurry. Brown on the outside, white on the inside. Speak no language good. Grossly tasteless, unidentifiable origins, no discernible value. You get the picture. If you’re not familiar with the term: there’s a sour piece on McNuggets in the Gulf here. I’m sure google will give a good yield if you seek more.

The guy in that article says it’s a generation who have rejected Arab culture because they watch too much Disney and prefer Happy Meals to sucking the marrow out of a mutton bone like they should. But I disagree (and I love marrow btw) because I don’t think it’s the chicken nuggets rejecting Arab culture – if there is any reason for a generation facing west – is it impossible to think it might be the culture rejecting us?

It can’t only be from lack of effort that my Arabic is a stub of what it should be.

Because I have really, really worked on it all of my life. In spite of not because of anyone who might have given me the tools when I was small and malleable.

I recently found a notebook I made one summer. It was a Mickey Mouse diary in which I had cobbled together my own language exercises and vocabulary tests based on things I overheard every day in the house.

But it would seem Arabic is really not a language for autodidacts.

I remember that even then with the little grey cells poised at the ready for retention, how hard it was to penetrate a root’s myriad meanings or get a handle on a famously baroque grammatical system without any real accessible guidance.

Often I feel like a sluggish mule buckling on the uphill to ‘language acquirement’. I struggle to find a reason to even use the words I carry. Meanwhile I watch all beleaguered while thoroughbred Oxford toffs translate bagfuls of rare manuscript and Muslim converts speckle every other syllable with PBUH. These guys trot all jaunty to the top of the tower.

And while Arabic might be a professional asset or a spiritual necessity for them – nothing is simple or easy to set your mind to when it’s an expectation laden minefield of emotional identity politics. Most people I know who struggle badly just end up lying about it or overcompensate by hyper focusing on their Arabness and maybe if they’re living outside of the region – they join the re-aspora of millennial Arab-North Americans and Arab-Europeans who come ‘back’ to learn Arabic or get jobs in the Gulf.

But it’s the elephant in our esophagus. A potential employer asks “Do you speak Arabic?” and you scan them to see if they might know better before saying, “Sure.” You’ve been coached through the shame of a negative answer into lying about it.

No one calls you out but you might live in a quiet fear wondering how bad of an imposter you are.

And feeling like a fraud is enough to make anyone turn their back on anything.

It’s actually tragic because it’s a sort of lingual brain drain and I’ve seen this more times than I can say.

Because a good education coupled with a good grasp of Arabic in the Gulf is a vanishingly rare commodity.

For me learning Arabic was never just hard, it hurt – it’s as if I had years of aversion therapy (which I won’t go into here) and eventually the words got sucked right out of my throat. Sea-witch-style.

But here’s the point of this whole blog post:

I’m not sure my linguistic failings are completely my fault any more.

And this weirdly healing thought came out of a conversation I had with a Kuwaiti friend who also struggles. Like me, he’s also made a LOT of effort to learn and spent a lot of money on classes and tutoring as an adult.

We discussed how there is a subtle rejection that happens. A sort of mistrust – even when you’re young. And the refusal to speak to that child in a particular language is a real thing. My father has never spoken to myself or my sister in Arabic. He will for a few sentences if I make the opening gambit – but inevitably he breaks back to English.

I had a Jordanian journalist snap at me when I refused to do a TV interview about my book with her. I said (in Arabic) it was because I wasn’t comfortable conducting it in Arabic (although it was probably more a fear of cameras). She huffed and laughed, “You’re an Arab. Why don’t you want to speak Arabic?”. That question. Thoughtless and exhausting. The encounter. Complex. (ps i swear she looked like Lady Tremaine in a hijab)

On the flip side of this – my father hasn’t taught my half-siblings English. He does not speak to them in English and just won’t. As a result, their educational and employment opportunities will never be as good as they should or could be no matter how brilliant they are.

What’s more I’m sure it’s not only Arabic – I have mixed Korean and Chinese friends who have experienced similar lingual and cultural rejection and as a result they have zero interest in visiting or being integrated into a culture that doesn’t seem to want them.

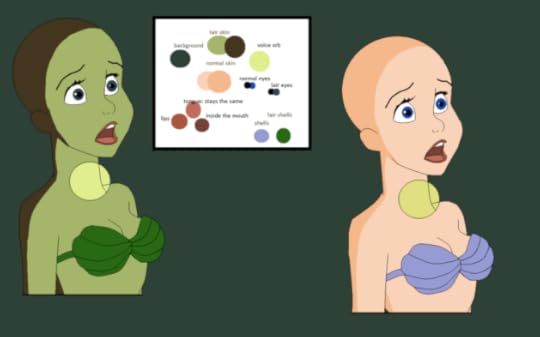

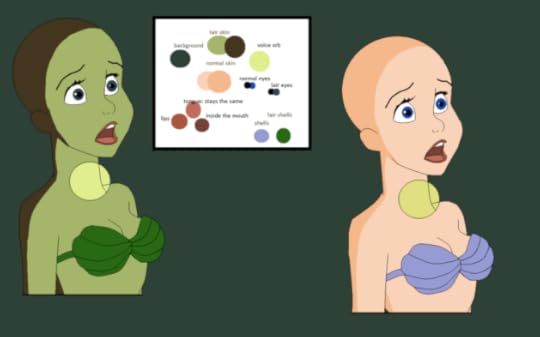

So this Little Mermaid is going to ask a few serious questions of whoever might read this because I really don’t know and I want to talk about this.

How dangerous and damaging is it to the future of a region if a language is linked specifically to cultural and ethnic identity?

If you’ve had parental units and education that encourage the full flowering of Arabic does that make you more of an Arab? If English comes easier to you – does that make you an agent of the west or some kind of imperialist/colonized subject? Because that seems to be the low key vibe of people like that journalist I mentioned. I’m amazed at how people seem to forget that Arabic is as much a colonising force as any European language. Think of the way pan-Arabists tried to erase Berber language and identity all across in North Africa.

And next time you see a pretty German girl on Arab Idol and get all up in a wad because you wonder “if she can do that then WTF is wrong with me!?” – just remember that the struggle is real and it’s a lifelong commitment.

Edward Said didn’t master Arabic until he was in his late 40s. Maybe that’s apocryphal. But at 32, it’s some kind of cold comfort. And until the technocrats figure out how to apply ‘deep learning’ algorithms to the human mind, I’ll just have to keep doing my vocabulary cards and reading the newspaper.

But anyway, at the very least we’ll always have “boooody languedge”.

Cry of the Chicken Nugget دوع التشيكن ناجت

How do you feel about this statement?

“An Arab is a person whose mother tongue is Arabic.”- Article 10, 1947 Ba’ath Constitution

I’m not one of these people who can pick up languages like shells on a seashore.

I have to be drowning just to work my way up to a fluent float and even then I barely keep my nose above the water.

If I’m not fully ‘immersed’? Well, the words just dry up in the sun. Evaporate on my tongue. And in some cases, leave an unpleasant aftertaste.

As an American, I imagine I probably modulate louder than I should in English (It’s hard to tell from inside your own head). And yet as an Arab – in Arabic – I’m usually ‘in the back on mute’.

There’s a pre-vocalised stammer when I use the father tongue, it’s like there’s something that jams whatever cortex controls speech and so opening my mouth releases a whole shoal of fears and insecurities and existential wobbles that I can’t really articulate.

But fuck it – Ima try.

Writing in English is now my job – and over the years – Arabic has become almost vestigial. It’s like a ghost limb that’s withered up from disuse. I retain the ability to write and read (and type 50 wpm blind) and yet the netting of this most beautiful alphabet is like a sieve that meaning just drains right tf out of.

I used to want to sing in Arabic but I’ve struggled to work up the guts to even speak.

99% of the time if a stranger in Egypt, Lebanon or Syria (the only places in the Arab world I have travelled without the visual signifier of my Abaya) ever asked where I was from they invariably would guess Morocco (which I guess basically means I don’t make sense and sound crazy). When I went to Morocco – that’s another story. My family in the Gulf used to call me ‘the Egyptian’. My accent now has the melted limey runoff of a person who’s been living in the UK for too long. Basically my language, like me, is a mess. SMH.

To clarify the title of this post Cry of the Curlew by Taha Hussein is the first novel in Arabic I ever attempted to read (and never finished I should add) and Chicken Nugget is the nickname for a generational cohort in the Gulf which I don’t identify as but maybe should. Like re-constituted chicken bits – a ‘Chicken Nugget’ is made from a lingual slurry. Brown on the outside, white on the inside. Speak no language good. Grossly tasteless, unidentifiable origins, no discernible value. You get the picture. If you’re not familiar with the term: there’s a sour piece on McNuggets in the Gulf here. I’m sure google will give a good yield if you seek more.

The guy in that article says it’s a generation who have rejected Arab culture. But I disagree because I don’t think it’s the chicken nuggets rejecting Arab culture – if there is any reason for a generation facing west – is it impossible to think it might be the culture rejecting us?

It can’t only be from lack of effort that my Arabic is a stub of what it should be.

Because I have really, really worked on it all of my life. In spite of not because of anyone who might have given me the tools when I was small and malleable.

I recently found a notebook I made one summer. It was a Mickey Mouse diary in which I had cobbled together my own language exercises and vocabulary tests based on things I overheard every day in the house.

But it would seem Arabic is really not a language for autodidacts.

I remember that even then with the little grey cells poised at the ready for retention, how hard it was to penetrate a root’s myriad meanings or get a handle on a famously baroque grammatical system without any real accessible guidance.

Often I feel like a sluggish mule buckling on the uphill to ‘language acquirement’. I struggle to find a reason to even use the words I carry. Meanwhile I watch all beleaguered while thoroughbred Oxford toffs translate bagfuls of rare manuscript and Muslim converts speckle every other syllable with PBUH. These guys trot all jaunty to the top of the tower.

And while Arabic might be a hobby or a professional asset or a spiritual necessity for them – nothing is simple or easy to set your mind to when it’s an expectation laden minefield of emotional identity politics. Most people I know who struggle badly just end up lying about it or overcompensate by hyper focusing on their Arabness and maybe if they’re living outside of the region – they join the re-aspora of millennial Arab-North Americans and Arab-Europeans who come ‘back’ to learn Arabic or get jobs in the Gulf.

But it’s the elephant in our esophagus. A potential employer asks “Do you speak Arabic?” and you scan them to see if they might know better before saying, “Sure.” You’ve been coached through the shame of a negative answer into lying about it.

No one calls you out but you might live in a quiet fear wondering how bad of an imposter you are.

And feeling like a fraud is enough to make anyone turn their back on anything.

It’s actually tragic because it’s a sort of lingual brain drain and I’ve seen this more times than I can say.

Because a good education coupled with a good grasp of Arabic in the Gulf is a vanishingly rare commodity.

For me learning Arabic was never just hard, it hurt – it’s as if I had years of aversion therapy (which I won’t go into here) and eventually the words got sucked right out of my throat. Sea-witch-style.

But here’s the point of this whole blog post:

I’m not sure my linguistic failings are completely my fault any more.

And this weirdly healing thought came out of a conversation I had with a Kuwaiti friend who also struggles. Like me, he’s also made a LOT of effort to learn and spent a lot of money on classes and tutoring as an adult.

We discussed how there is a subtle rejection that happens. A sort of mistrust – even when you’re young. And the refusal to speak to that child in a particular language is a real thing. My father has never spoken to myself or my sister in Arabic. He will for a few sentences if I make the opening gambit – but inevitably he breaks back to English. On the flip side he hasn’t taught my half-siblings English. He does not speak to them in English and just won’t. As a result, their educational and employment opportunities will never be as good as they should or could be.

What’s more I’m sure it’s not only Arabic – I have mixed Korean and Chinese friends who have experienced similar lingual and cultural rejection and as a result they have zero interest in visiting or being integrated into a culture that doesn’t seem to want them.

So this Little Mermaid is going to ask a serious question of whoever might read this b/c IRDK.

How dangerous and damaging is it to the future of a region if a language is linked specifically to cultural and ethnic identity?

And next time you see a pretty German girl on Arab Idol and get all up in a wad because you wonder “if she can do that then WTF is wrong with me!?” – just remember that the struggle is real and it’s a lifelong commitment.

Edward Said didn’t master Arabic until he was in his late 40s. Maybe that’s apocryphal. But at 32, it’s some kind of cold comfort. And until the technocrats figure out how to apply ‘deep learning’ algorithms to the human mind, I’ll just have to keep doing my vocabulary cards and reading the newspaper.

But anyway, at the very least we’ll always have “boooody languedge”.

September 18, 2015

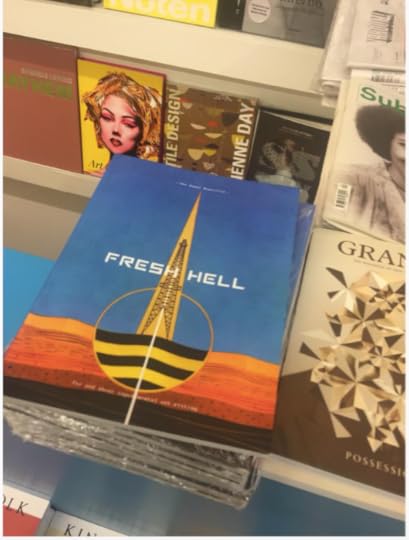

The Happy Hypocrite VIII – Fresh Hell

So HAPPY to post the fact that my guest edited issue of Maria Fusco’s long-running experimental art writing journal The Happy Hypocrite.

Is out.

With contributions and new work by Abdullah Al-Mutairi, Monira Al Qadiri, Stephanie Bailey, Alex Borkowski, Judy Darragh, William Gibson, Navine G. Khan-Dossos, Malak Helmy, Raja’a Khalid, Omar Kholeif, McKenzie Wark, Simon Sellars, Francesco Pedraglio and Lena Tutanjian.

You can purchase here and here. And hopefully many other locations soon!

Launch events TBA in London + DXB soon.

‘What fresh hell is this? There’s an inferred question in the title of this issue. But it’s a rhetorical one. Because we know exactly what fresh hell this is. Fossil Fuel – that paralytic drug – has leeched into our collective bloodstream. It’s difficult to recognize the beasts that are eating us in this very moment.’ – Sophia Al-Maria, from the Editor’s note, The Happy Hypocrite 8

The Happy Hypocrite – Fresh Hell treats in different ways the subject of oil. Adopting an exploded methodology for intake, image and text contributions, this issue takes a hoarding, brutally accelerative approach and considers reading, too, as an unsustainable activity. Guest editor Sophia Al-Maria’s archive acts a sort of proto-Tumblr composed of school notebooks, war games and oil industry pamphlets scattered as a series of identifying clues. All windows are open, all browsers are burning: The Happy Hypocrite asks what happens when reblogged information is translated into paper-based print.

July 25, 2015

DAY 59 – E-FLUX – SUPERCOMMUNITY – TBH IDK FTW

It’s Day 59 of e-flux Supercommunity & all I can say is – “to be honest i don’t know f*ck the world”.

I wrote this piece reflecting on the fact that I have had one mother of a case of writer’s block due in part to the internet and in another part to a depressive funk I’ve been simmering in.

Said funk was relating to feeling hopeless and helpless in the gaping maw of the world’s impossible order. One thing I’ve come to acknowledge struggling through it without any methodology and nothing but this app for therapeutic assistance is that having people – having a community – in fact – having a super community – really fucking helps.

Obvious to you maybe but I’ve always been a Sartre kind of a girl thinking hell is other humans.

So I call it a revelation.

Anyway, it’s not a sustained piece of criticism or anything particularly vital as several of the Supercommunity’s other works have been. It’s written in the cadence of an internet-hooked mind. Peripatetic. Factoid-filled. Rambling.

And I have to say, for all the complaints I’ve heard about Supercommunity feeling a little spammy in its daily-ness since the Venice launch – it’s yielded some truly juicy, incredible stuff.

This is an illustration e-flux rigged up depicting the epitaph Dorothy Parker would have liked on her tombstone. The reason this whole piece is preoccupied with the Parker (feminist and civil rights activist as well as now unfashionable writer) is that I’ve been guest editing Maria Fusco’s Happy Hypocrite journal for experimental art writing and have named it Fresh Hell after a Parker quote. More on that later.

So on that final note. Here are 3 choicer cuts of the Supercommunity I’ve enjoyed this summer:

Adrian Lahoud’s Nomos & Cosmos

Hu Fang’s Why We Look @ Plants in a Corrupted World

and

Kader Attia’s The Loop

oooxxxooo

April 20, 2015

SISTERS @ NEW MUSEUM TRIENNIAL

I spend a lot of time creepin.

Then I make videos out of what I find. One of these is currently at the New Museum in NYC as part of the Triennial Surround Audience co-curated by Lauren Cornell and Ryan Trecartin.

Sisters is a four-channel video composed mostly of found footage from WhatsApp and Youtube.

These fleeting moments online hold a poignant power to me. It’s inexplicable but I think everyone who watches one of these videos slowed down or retextualized outside of a lurid website or a clandestine mobile phone peek feels that.

It is contact.

And there��is a��ghostly power these��girls have, almost like digital shadows of themselves but the perfect imitation of flesh. They reverberate with��power��and the videos themselves have a strange gestational pulse. Hearts beat through sheaths of transparent PVC.

The images��are stretched on long transparent screens, slightly��higher than the viewer in order to create a sort of elgreco-effect. Each hosting one of these elongated lo res sirens.

They wrote a few paragraphs of ‘context’ at the actual Triennial but you can read it there for a limited time only (until May 24th)!

Sophia Al-Maria's Blog

- Sophia Al-Maria's profile

- 34 followers