E.G. Wolverson's Blog, page 19

July 18, 2013

Book Review | Glue by Irvine Welsh

Anyone who read my lengthy celebration of Trainspottingin its two most famous forms was probably half-dreading my inevitable, interminable musings on the super-heavyweight of a tome with which it shares a sequel. But for all its heartbreaking depth and crippling charm, there is far less to say about Irvine Welsh’s Gluethan there is its principal forerunner. Trainspotting was an episodic melting pot that dragged its readers from tale to tale at breakneck speed, whereas Glue is much more structured and specific. It maintains the snapshot-styled structure of Welsh’s first novel, but instead of a 36-exposure film of disposable camera six by fours, Glue’s four snapshots are huge, panoramic vistas; each set a decade or so apart, and each offering its four focal characters’ different perspectives on a formative event - or its aftermath.

Anyone who read my lengthy celebration of Trainspottingin its two most famous forms was probably half-dreading my inevitable, interminable musings on the super-heavyweight of a tome with which it shares a sequel. But for all its heartbreaking depth and crippling charm, there is far less to say about Irvine Welsh’s Gluethan there is its principal forerunner. Trainspotting was an episodic melting pot that dragged its readers from tale to tale at breakneck speed, whereas Glue is much more structured and specific. It maintains the snapshot-styled structure of Welsh’s first novel, but instead of a 36-exposure film of disposable camera six by fours, Glue’s four snapshots are huge, panoramic vistas; each set a decade or so apart, and each offering its four focal characters’ different perspectives on a formative event - or its aftermath.The first time that I read Glue, I was surprised to discover that its title wasn’t an allusion to tales of substance abuse therein, but rather the metaphorical ties that bind a motley crew of Edinburgh lads from their shared working class background to destinies summed up by either fame, fortune, fornication or fatalism. Whilst still laden with the phonetic Scots dialogue common to almost all of Welsh’s works, the novel is characterised by glorious and evocative prose that occasionally threatens to undermine the characters’ independence. You can feel the omniscience creeping in as protagonists note “the dramas of future despair in pre-production” and ruminate upon anthropomorphised time “ripping the guts out of people, then setting them in stone and just slowly chipping away at them”. Indeed, the latter quote effectively sums up Glue’s mission statement as Welsh takes four boys, four families, and slowly melts them - all so that the reader may draw in their intoxicating fumes.

Rather than make a number of profound points through sharp machete moralising, Glue offers a ceaseless succession of astute and pointed ones; many trivial, others far from being such. I love the blend of the two; love how Welsh uses roughly the same number of words to convey one character’s paltry realisation that he’s just on the wrong side of a paradigm shift in male grooming, much to the detriment of his status in the middle-aged meat market, as he does another’s that he’s thrown his whole life away in a fleeting lapse of juvenile reason; the unthinking, spur-of-the-moment loan of a knife. The touching, old-age death of one of the first characters that we meet in the book sits sandwiched between Terry’s patented “shag, shit, shave, shower” hangover cure recital and ginger-pube medical fantasy. Lives are saved by beer guts; psychos turned into Daleks with crossbows. And all the while, Glue remains resplendently true to life; true to the wacky adventures borne of friendships and the peculiar protocols that they engender.

And due to the level of exposure that Glue affords them, its four focal characters - Andrew Galloway, Billy ‘Business’ Birrell, Carl ‘N-Sign’ Ewart, and ‘Juice’ Terry Lawson - become just as familiar to the reader as those that headlined Trainspottingand would be revisited in Porno, Skagboys, and, in a few fleeting cameos, this book too. Birrell’s a likeable, stand-up guy; a boxer with the skill to be champion of the world, but not the constitution. Carl’s the pale and pasty ‘Milky Bar Kid’ destined to deejay despite falling foul of the press in an incident from which, in ‘Juice’ Terry-inspired defiance, he’d take his stage name. And then there’s perr wee Gally, whose tragedies follow each other in a domino-like cascade.

And due to the level of exposure that Glue affords them, its four focal characters - Andrew Galloway, Billy ‘Business’ Birrell, Carl ‘N-Sign’ Ewart, and ‘Juice’ Terry Lawson - become just as familiar to the reader as those that headlined Trainspottingand would be revisited in Porno, Skagboys, and, in a few fleeting cameos, this book too. Birrell’s a likeable, stand-up guy; a boxer with the skill to be champion of the world, but not the constitution. Carl’s the pale and pasty ‘Milky Bar Kid’ destined to deejay despite falling foul of the press in an incident from which, in ‘Juice’ Terry-inspired defiance, he’d take his stage name. And then there’s perr wee Gally, whose tragedies follow each other in a domino-like cascade.The novel’s superlative superstar though is the outmoded aerated water salesman who is, and probably forever will be, my favourite Welsh character. With his fierce arsenal of misogynistic quips that’d make Gene Hunt blush (“...a bird’s bush in your hand is worth two wi thir clathes oan...” / “A souvenir ay Blackpool…? Yir better ridin birds than trams, better lickin fannies thin sticks ay rock...”) and the brash confidence of a man whose erection is reputed to be “like one tin ay Irn-Bru stuck oan top ay another”, the corkscrew-heided tea-leaf is more outstanding than Franco Begbie. He’s even got a cunning that, to his delight and often-milked advantage, few people can see - until it’s too late. Every passage that he features in is sheer delight to read, suffused with guilty pleasure and begrudging admiration. Every passage, I should say, but one.

On both occasions that I’ve read it, despite having comparatively little to say about it (without utterly ruining its plot, anyway), I’ve been left with the nagging sense that this turn-of-the-millennium rollercoaster Scots epic is, perhaps, Welsh’s finest work. Though it’s often ugly, as grim cause and harrowing effect are more pivotal players than the protagonists whose lives we are sucked into, it sensationally showcases “the spice ay life”; the passions and prejudices of a small pond’s big fish that ultimately prove alluring enough to inspire and ignite even an anorexic American songstress who’s lost her lust for life. Irvine Welsh’s Glue is currently available in paperback (best price online today: £5.44 from AbeBooks) and digital formats (£5.98 from Amazon's Kindle Store or £6.49 from iTunes).

Published on July 18, 2013 04:52

July 4, 2013

Beyond History’s End | 50th Anniversary Doctor Who Review 6 of 12 | The Curse of Davros written by Jonathan Morris, The Fourth Wall written by John Dorney and The Wrong Doctors written by Matt Fitton

As long as Matt Smith remains playing the part of the series’ titular Time Lord, Colin Baker will be able to keep on referring to himself as its “central Doctor”. Whilst it doesn’t have the same ring to it that “Old Sixy” does, the sixth Doctor’s latest nom de guerre really struck a chord with me as it encapsulates perfectly my feelings toward the multi-coloured cat that walks through time - at least insofar as his aural exploits go. For more than a decade now, Baker’s Doctor has been the backbone of the company’s flagship Doctor Who monthly range, not to mention the incarnation that lays claim to the greatest share of its most-prized offerings. You’ll find fewer missteps and more enduring hits in Colin Baker’s back catalogue than you will Tom Baker’s, Peter Davison’s, Sylvester McCoy’s, or even Paul McGann’s. And it’s largely for this reason that I find myself unable to restrict my pontificating here to his January 2012 offering, as I had originally planned. Instead, I’m going to tackle three four-part adventures from the last two years: The Curse of Davros (January 2012), The Fourth Wall (February 2012) and The Wrong Doctors (January 2013).

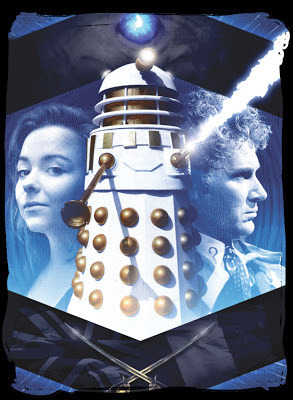

The trilogy-opening - some might say era-opening - Curse of Davros is a funny onion. Gleefully eschewing the weight of earlier Doctor / Davros audio encounters, Jonathan Morris’s four-parter meanders between the moods of The Chase and Jubilee. As Joseph Lidster had drained every last ounce of audible angst from Davros in 2005’s Terror Firma, which marked the Dalek creator’s last Big Finish appearance opposite the Doctor prior to this, it’s easy to see why he was brought back in a story that’s so far removed from Davros, The Juggernauts and Terror Firma that it’s almost impossible to view it in the same context. Those pieces were carried, defined and I would say elevated by some seminal sparring between the Doctor and his twisted nemesis, but that just isn’t on the cards here; at least not in a familiar form. Hell, Terry Molloy hardly utters a word in the first half of this story despite it being dominated by Davros. The Doctor, in contrast, is uncharacteristically contained; his first and second episode appearances typified by confined, brooding sort of scheming that you’d normally expect from his opposite number. This is, in essence, the central theme of the play, as it studies what it’s like to walk mile in another man’s shoes to mostly comic, but occasionally unnerving, effect. Both Baker and Molloy seem to relish the unique opportunity that the story presents them with, taking the aptitude and passion that made the almost exclusively two-hand Davros a classic and turning it to a new, unexpected purpose.

To my surprise though, the play’s most stirring moments didn’t feature Davros at all - the crippled genius has a fighting force of unusually-loyal Imperial Daleks in tow to do his bidding this time, albeit in a revolutionary new form. Now able to transfer their consciousnesses into the bodies of human beings, these Daleks are able to cut out middle-men duplicates and insidiously take over the 21st century authorities directly. They’re able to displace the minds of the men fighting at Waterloo on that fateful Sunday in the summer of 1815, and fight that battle in their stead, much to the ruin of established history - and, most terrifyingly, the men who suddenly find themselves in the body of a Dalek mutant. There is a scene in this play in which one of the characters describes what it felt like to be a Dalek, and it’s absolutely horrifying; almost too ghastly for worlds. The ubiquitous taste of vomit. The feeling of being burned alive. The in-built, genetic anger; a never-ending rage fuelled by nothing more than biology. It’s masterfully written and perfectly played.

To my surprise though, the play’s most stirring moments didn’t feature Davros at all - the crippled genius has a fighting force of unusually-loyal Imperial Daleks in tow to do his bidding this time, albeit in a revolutionary new form. Now able to transfer their consciousnesses into the bodies of human beings, these Daleks are able to cut out middle-men duplicates and insidiously take over the 21st century authorities directly. They’re able to displace the minds of the men fighting at Waterloo on that fateful Sunday in the summer of 1815, and fight that battle in their stead, much to the ruin of established history - and, most terrifyingly, the men who suddenly find themselves in the body of a Dalek mutant. There is a scene in this play in which one of the characters describes what it felt like to be a Dalek, and it’s absolutely horrifying; almost too ghastly for worlds. The ubiquitous taste of vomit. The feeling of being burned alive. The in-built, genetic anger; a never-ending rage fuelled by nothing more than biology. It’s masterfully written and perfectly played.The principal plot, however, is just a little too far-fetched as it rests on the listener accepting that Davros (a) admires a human being, albeit one as autocratic as Napoleon Bonaparte; and (b) would wish to help the human race fulfil what he sees as its military potential, albeit to the favour of the Daleks. I just can’t see him admiring anyone but himself and his creations, and I certainly couldn’t see him acknowledging the martial merits of any species that he didn’t create. Ultimately though, it doesn’t really matter as the main plot is meant to be a colourful backdrop to the character comedy and drama, and in these terms it succeeds admirably.

Probably The Curse of Davros’s main talking point though is the new companion that it introduces - or, rather, reintroduces. Having impressed most of those who listened to The Crimes of Thomas Brewster, Lisa Greenwood returns to reprise the role of Philippa ‘Flip’ Jackson as a fully-fledged companion, and this time she really knocks it out of the park. This is quite remarkable, really, as by all rights this type of contemporary character should seem stale by now. Flip takes the brashest shades of Donna, Rose and even Big Finish’s own Lucy, and amplifies them with the brazen frankness of youth. Hailing as she does from a world of JLS, supermarkets and stilettos, Flip is perhaps the ‘safest’ companion that Big Finish have created in-house, but particularly now that the television series insists upon producing companions whose existences are each somehow wound around the Doctor’s contrived, season-spanning arcs, I’m quite happy for them to take the tried and tested ‘Doctor meets average girl’ trope and run with it. And John Dorney just happened to run with it straight through a wall; The Fourth Wall, in fact.

After the off-kilter action of The Curse of Davros, I had expected the Doctor and Flip’s second adventure to have a much more solid, traditional flavour, but, if anything, it is even more of a concept piece than the story that it follows. With the first-ever Companion Chronicle audio play (as opposed to prose-driven audio book) and an aberrant fourth Doctor historical already under his belt, here John Dorney turns his ever-inventive mind to the human predilection for drama; the omniscience of writers; and the moral consequences of the same - issues that I find especially fascinating as they informed aspects of my own novel, The Tally. Borne of Dorney’s averseness to inflict gratuitous suffering and death upon his own fictional creations, these four episodes explore the creation of a new form of entertainment and the rise to sentience of its woefully-shallow protagonists, who suddenly find themselves pawns in the game of the man who created them - their god, as it were.

After the off-kilter action of The Curse of Davros, I had expected the Doctor and Flip’s second adventure to have a much more solid, traditional flavour, but, if anything, it is even more of a concept piece than the story that it follows. With the first-ever Companion Chronicle audio play (as opposed to prose-driven audio book) and an aberrant fourth Doctor historical already under his belt, here John Dorney turns his ever-inventive mind to the human predilection for drama; the omniscience of writers; and the moral consequences of the same - issues that I find especially fascinating as they informed aspects of my own novel, The Tally. Borne of Dorney’s averseness to inflict gratuitous suffering and death upon his own fictional creations, these four episodes explore the creation of a new form of entertainment and the rise to sentience of its woefully-shallow protagonists, who suddenly find themselves pawns in the game of the man who created them - their god, as it were.Despite the heavy philosophical nature of its subject matter, The Fourth Wall is a startlingly buoyant affair with a tone that is constantly segueing between sensation and satire; ferocity and farce. One moment, a character can be lost in a vitriolic monologue, renouncing the harrowing back story wantonly imposed on him by his writer; the next, another character can be arguing with the actress portraying her over who’s the prettiest. Picture one of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Moriarty holodeck episodes, only filled with incompetent porcine warlords instead of bald and bold human explorers, and you’re just about there.

The Fourth Wall’s tonal volatility extends to the Doctor and Flip, who quickly go from a sardonic squabble over the Space / Time Visualiser’s surprising lack of colour resolution to being separated by the fourth wall of the title, and then on to something altogether more sinister. Such constant flitting leaves the listener on edge throughout, uncertain as to whether death or humour lies in wait around the next narrative corner. It’s my ideal blend.

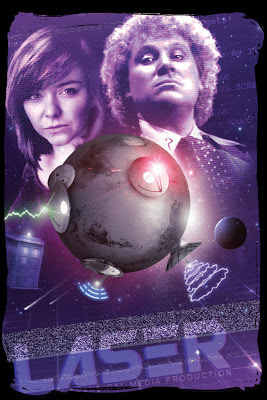

Fast-forward eleven months for the audience and half a life for Old Sixy, and newcomer Matt Fitton opens the series’ anniversary year for Big Finish’s flagship range with a celebratory adventure that sits somewhere between traditional multi-Doctor romp and a fanboy’s wet dream, The Wrong Doctors. Before I listened to this play, I had an inkling that I’d fall head over heels for it, taking as it does one of Doctor Who’s most intricate continuity points and complicating it even further still, and it seems that I know myself all too well - this four-parter is a top birthday present, almost on a par with The Name of the Doctor.

Fast-forward eleven months for the audience and half a life for Old Sixy, and newcomer Matt Fitton opens the series’ anniversary year for Big Finish’s flagship range with a celebratory adventure that sits somewhere between traditional multi-Doctor romp and a fanboy’s wet dream, The Wrong Doctors. Before I listened to this play, I had an inkling that I’d fall head over heels for it, taking as it does one of Doctor Who’s most intricate continuity points and complicating it even further still, and it seems that I know myself all too well - this four-parter is a top birthday present, almost on a par with The Name of the Doctor. Of course, as with any story in the spin-off media that might sit ill with others that have preceded it, there is bound to be a little resistance from some quarters of fandom. However, Fitton’s script is so deliciously devious that even those who will listen to it weeping, clutching their battered old copies of Business Unusual to their bosoms, are sure to be won over by its “cauterised time”, memory erasures and never was, Vortex-dwelling antagonists. If I was still in the business of pedalling Continuity Corners, I’d have had a field day here - my prepositional musings would probably have been longer than this entire article.

Of course, as with any story in the spin-off media that might sit ill with others that have preceded it, there is bound to be a little resistance from some quarters of fandom. However, Fitton’s script is so deliciously devious that even those who will listen to it weeping, clutching their battered old copies of Business Unusual to their bosoms, are sure to be won over by its “cauterised time”, memory erasures and never was, Vortex-dwelling antagonists. If I was still in the business of pedalling Continuity Corners, I’d have had a field day here - my prepositional musings would probably have been longer than this entire article.Fitton’s story is built on the long-upheld idea that following the conclusion of The Trial of a Time Lord, the relatively young, very brash and offensively-colourful sixth Doctor returned key witness and not-met-yet companion Melanie Bush to her home village of Pease Pottage so that his older self (with whom she was travelling prior to being plucked out of time by the Time Lords) could collect her at his convenience and they could resume their adventures together - and he could do his level best to postpone their inevitable meeting and all the carrot juice-fuelled aerobics sessions that would follow it. As The Wrong Doctors’ first episode opens, a sixth Doctor who’s audibly far closer to the one of television fame than the more kindly fellow that Big Finish have brought to the fore, deposits his future friend in a Pease Pottage that isn’t quite the Pease Pottage that she remembers. Keen to be away, he doesn’t even stop to check the date and heads back to the TARDIS. Meanwhile, having polished off the last slice of Evelyn’s trademark chocolate cake, the Necros-blue Sixy that we all know and love decides that it’s time he catches up with his future, and so sets course for Pease Pottage where he expects to meet an eager computer programmer with the memory of an elephant who can scweam and scweam and scweam. Imagine his surprise when, instead, he finds his younger self in need of an attitude adjustment; a childlike Mel who shows little prospect of developing into the bright young woman that he met during his trial; an unhappy and displaced, yet worryingly familiar, Mel deposited by his younger self; and “a temporal daisy chain” that has pulled two centuries’ worth of events into one maelstrom of a Pease Pottage present. This isn’t just business unusual; it’s business unique.

The whole play is charged with a lovely sense of mischief as Fitton not only stretches the opportunities that a fateful quirk of continuity presented him with, but the fact that he’s writing the story with twenty-odd years’ hindsight too. The dialogue is often laugh-out-loud funny - take the Doctor’s assignment of letters to distinguish the Mels, prompting a flurry of decade-too-early Spice Girls jokes, for instance, or his description of the Time Demon as “an aftermath with malice of forethought” - and even the events themselves have a farcical edge that the cast really play up to; the double-duty Colin Baker and Bonnie Langford especially. There are shades of Caerdroia in the incarnation-specific, multi-Doctor quarrelling that burns throughout the first half of the story, though I think that Fitton and Baker are able to have a lot more fun with their sixth Doctors here than Lloyd Rose and Paul McGann had with their three eighths in 2004, as this adventure portrays two sixth Doctors that we recognise, as opposed to three discrete aspects of the eighth Doctor’s personality incarnate. And in many ways, what Fitton and Langford do with Mel is even more interesting. I won’t spoil the surprises for those yet to listen to the play; suffice it to say that the entire plot turns on some of Mel’s signature characteristics that are notably absent in her antecedent, and Langford does the finest of jobs in making the listener take notice.

The whole play is charged with a lovely sense of mischief as Fitton not only stretches the opportunities that a fateful quirk of continuity presented him with, but the fact that he’s writing the story with twenty-odd years’ hindsight too. The dialogue is often laugh-out-loud funny - take the Doctor’s assignment of letters to distinguish the Mels, prompting a flurry of decade-too-early Spice Girls jokes, for instance, or his description of the Time Demon as “an aftermath with malice of forethought” - and even the events themselves have a farcical edge that the cast really play up to; the double-duty Colin Baker and Bonnie Langford especially. There are shades of Caerdroia in the incarnation-specific, multi-Doctor quarrelling that burns throughout the first half of the story, though I think that Fitton and Baker are able to have a lot more fun with their sixth Doctors here than Lloyd Rose and Paul McGann had with their three eighths in 2004, as this adventure portrays two sixth Doctors that we recognise, as opposed to three discrete aspects of the eighth Doctor’s personality incarnate. And in many ways, what Fitton and Langford do with Mel is even more interesting. I won’t spoil the surprises for those yet to listen to the play; suffice it to say that the entire plot turns on some of Mel’s signature characteristics that are notably absent in her antecedent, and Langford does the finest of jobs in making the listener take notice.

But for all its subversive humour, The Wrong Doctors is an absolutely first-class piece of sci-fi too, its complex continuity punctuated with all the twists and scares that one would expect from Doctor Who. Even these often come from outside the normal Who sphere though, as Fitton turns to mellifluous melodies for menace and a historical preservation society to rob the world of its future. It’s terrifying to think that Big Finish found this guy’s ideas languishing in their short-lived slush pile, because his debut script is one of the most modern, well-rounded and most entertaining that they’ve given life to for quite a while.

But for all its subversive humour, The Wrong Doctors is an absolutely first-class piece of sci-fi too, its complex continuity punctuated with all the twists and scares that one would expect from Doctor Who. Even these often come from outside the normal Who sphere though, as Fitton turns to mellifluous melodies for menace and a historical preservation society to rob the world of its future. It’s terrifying to think that Big Finish found this guy’s ideas languishing in their short-lived slush pile, because his debut script is one of the most modern, well-rounded and most entertaining that they’ve given life to for quite a while.I hope that this little sixth Doctor digest demonstrates that, whilst he’s seldom given his due by the Who-faring general public, and he’s soon to lose his numerical place as “central Doctor”, Colin Baker’s Old Sixy is still the cornerstone of the whole Whoniverse to many. And as long as there are writers the calibre of Jonathan Morris, John Dorney and Matt Fitton to fuel his exploits with episodes the quality of the dozen that I’ve touched upon here, then he will continue to be for many years to come.

The Curse of Davros, The Fourth Wall and The Wrong Doctors are each available to download from Big Finish for just £12.99. The CD versions (which also come with a free download) are just £14.99. Subscribers to the monthly range not only pay less overall (a 6-release CD subscription is just £70.00; a 12-release £140.00), but in addition, if their subscriptions cover a December release, they will automatically receive a special bonus release too. 12-release subscriptions also include a free additional release of the subscriber’s choice priced at £10.99 or less, and entitle the subscriber to a £5.00 discount on either a 12-release Companion Chronicles subscription or a season subscription to The Eighth Doctor Adventures.

The universe stands on the brink of a dimensional crisis – and the Doctor and Raine are pulled into the very epicentre of it.

Meanwhile, on Earth, UNIT scientific advisor Dr Elizabeth Klein and an incarnation of the Doctor that she’s never encountered before are tested to the limit by a series of bizarre, alien invasions.

At the heart of it all is a terrible secret, almost as old as the Time Lords themselves. Reality is beginning to unravel and two Doctors, Klein, Raine and all of UNIT must use all their strength and guile to prevent the whole of creation being torn apart.

Read retro Doctor Who reviews @

Published on July 04, 2013 03:56

June 25, 2013

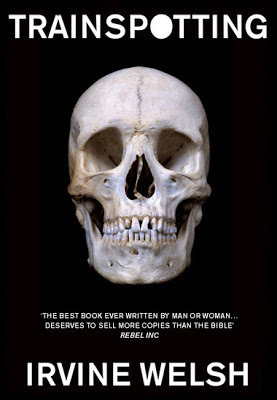

Prose vs Pictures #1 | Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting vs Danny Boyle's Trainspotting

When I decided to embark upon this Prose vs Pictures journey, I had a number of contests in mind that were foregone conclusions – books that I feel are inviolate, largely, but also movies that embellish and enlarge some already magnificent texts. But with Trainspotting, which my recent enjoyment of its prequel had made an obligatory series opener, I honestly had no idea which way my gavel would fall. I’d read Irvine Welsh’s game-changing novel just once, many years ago, and thought that it was one of the most brutal and thought-provoking digests of human nature that I’d ever come across – yet extraordinarily funny too. On the other hand, I must’ve watched Danny Boyle’s movie five or six times since its theatrical release, and have always seen it as being as pivotal a part of the 1990s’ fabric as Eric Cantona’s kung-fu kicks; ill-fated England / Germany penalty-shootouts; or even the blazing Britpop battle between Blur and Oasis.

Reading Trainspotting again in 2013, I was first struck by how fresh it all felt, even twenty years into publication. As much of it was originally published in piecemeal form across various publications, its chapters are more akin to short stories than they are segments of an overarching narrative. Each episode has a clear beginning, middle and punchline. Each episode is told by a different voice, often in a different tense, offering insights that range from omniscient to violently constricted. This makes the book easier to dip in and out of than most fiction, though its accessibility is of course hindered by its brazen eschewing of… well, English. Welsh caused quite the literary stir by presenting most of the book in phonetically-transcribed Scottish with scant punctuation and unconventional (but far from unprecedented) hyphens preceding its dialogue, as opposed to mainstream literature’s encapsulating quote marks. However, this unusual approach is in some respects the book’s making, as it makes the text instantly stand out to the reader as being something unique and, perhaps, illicit; qualities that follow in abundance as Welsh wastes no time at all in launching into rapturous accounts of heroin use that, inevitably, saw both the book and film slammed for being pro-drugs by those who didn’t make it past the first few chapters / opening scenes. Read up to the amputations and brain abscesses, and tell me who’s pro-skag then.

Reading Trainspotting again in 2013, I was first struck by how fresh it all felt, even twenty years into publication. As much of it was originally published in piecemeal form across various publications, its chapters are more akin to short stories than they are segments of an overarching narrative. Each episode has a clear beginning, middle and punchline. Each episode is told by a different voice, often in a different tense, offering insights that range from omniscient to violently constricted. This makes the book easier to dip in and out of than most fiction, though its accessibility is of course hindered by its brazen eschewing of… well, English. Welsh caused quite the literary stir by presenting most of the book in phonetically-transcribed Scottish with scant punctuation and unconventional (but far from unprecedented) hyphens preceding its dialogue, as opposed to mainstream literature’s encapsulating quote marks. However, this unusual approach is in some respects the book’s making, as it makes the text instantly stand out to the reader as being something unique and, perhaps, illicit; qualities that follow in abundance as Welsh wastes no time at all in launching into rapturous accounts of heroin use that, inevitably, saw both the book and film slammed for being pro-drugs by those who didn’t make it past the first few chapters / opening scenes. Read up to the amputations and brain abscesses, and tell me who’s pro-skag then.

It was to Danny Boyle’s credit that his film adaptation looked to transfer Trainspotting’s most extraordinary qualities onto the silver screen without any attempt to dilute them for a wider audience. If Irvine Welsh’s Trainspottingis a broken-up jigsaw that readers have to piece together, John Hodge’s screenplay assembles the centre of the picture for everyone to see, omitting only the fine detail on the outermost pieces. Make no mistake, there is a broadly linear and progressive narrative in the book, and ninety percent of the film’s storyline has been cut and pasted from it, but the movie holds the audience’s hands between A and B and C in a way that the novel never did, occasionally reshuffling events for the sake of sense or sensation. Clever contrivances such as Renton’s theft of the Tommy / Lizzie sex tape, the Beggar’s Boy’s blag gone wrong and jailbait Diane’s correspondence enable Hodge to link discrete episodes – discrete eras, really – in the book without the viewer even batting an eye.

It was to Danny Boyle’s credit that his film adaptation looked to transfer Trainspotting’s most extraordinary qualities onto the silver screen without any attempt to dilute them for a wider audience. If Irvine Welsh’s Trainspottingis a broken-up jigsaw that readers have to piece together, John Hodge’s screenplay assembles the centre of the picture for everyone to see, omitting only the fine detail on the outermost pieces. Make no mistake, there is a broadly linear and progressive narrative in the book, and ninety percent of the film’s storyline has been cut and pasted from it, but the movie holds the audience’s hands between A and B and C in a way that the novel never did, occasionally reshuffling events for the sake of sense or sensation. Clever contrivances such as Renton’s theft of the Tommy / Lizzie sex tape, the Beggar’s Boy’s blag gone wrong and jailbait Diane’s correspondence enable Hodge to link discrete episodes – discrete eras, really – in the book without the viewer even batting an eye.

The content itself is frighteningly faithful to the book too; Hodge even goes so far as to use after-the-event voiceovers on present events so as to preserve Welsh’s phraseology almost exactly, as he does, for instance, in the nightclub scene that sees Renton narrate his first encounter with Diane. Inevitably though, great swathes of material doesn’t make it to the screen. The tale of Tommy and Second Prize’s disastrous public house chivalry; Davie Mitchell’s retribution against infectious rapist Alan Venters; even feminist Kelly’s rat poison restaurant revenge, duly framed by her looming and strikingly-pertinent essay on morality, were just a few of the cuts that I found hard to bear. I must concede though that these, and indeed almost all of the tales not used for the film, are too remote from Renton and Sick Boy et al to have warranted inclusion, and for the most part Hodge and Boyle got it exactly right; they even passed stool-spilling sheets from one character to another in an attempt to mitigate the losses.

The content itself is frighteningly faithful to the book too; Hodge even goes so far as to use after-the-event voiceovers on present events so as to preserve Welsh’s phraseology almost exactly, as he does, for instance, in the nightclub scene that sees Renton narrate his first encounter with Diane. Inevitably though, great swathes of material doesn’t make it to the screen. The tale of Tommy and Second Prize’s disastrous public house chivalry; Davie Mitchell’s retribution against infectious rapist Alan Venters; even feminist Kelly’s rat poison restaurant revenge, duly framed by her looming and strikingly-pertinent essay on morality, were just a few of the cuts that I found hard to bear. I must concede though that these, and indeed almost all of the tales not used for the film, are too remote from Renton and Sick Boy et al to have warranted inclusion, and for the most part Hodge and Boyle got it exactly right; they even passed stool-spilling sheets from one character to another in an attempt to mitigate the losses. The only omissions that I could complain about are those that do adversely affect the film’s highlighted quartet, Renton in particular. His once-abused and now-frigid paramour, Hazel, is absent throughout (her occasional incidental appearances are usurped on screen by Spud’s inherited-from-Davie Mitchell girlfriend, Gail, played by Welsh stalwart Shirley Henderson), as is any mention of his deceased, disabled brother. Even something as crucial as his other brother’s death whilst serving with the military in Ireland, and its political ramifications for his half-Weedgie / Orange clan, not to mention his surviving missus, is completely left out. Particularly when combined with Rents inheriting some of Sick Boy’s crueller scenes, such as the notorious “dug shooting” escapade and giving Tommy his first shot of junk, one’s perception of Renton becomes slightly less sympathetic on screen.

Oddly, the film’s most obvious departure from Welsh’s work makes the easiest transition across the media. In the novel, it isn’t Tommy but Matty who dies so horribly, and whose funeral serves as a palpable memento mori to his surviving junky friends. What the film cleverly latches onto is the idea that Tommy – especially when he’s played so genuinely by future Rome star Kevin McKidd – is the instantly-recognisable straight, easygoing presence that you’ll find in even the most lawless parcel of rogues, whereas the novel’s Matty was a whining and obnoxious dickhead. In the book, Tommy does split from Lizzie, get on heroin and contract HIV, leading to the superlatively grim “Winter in West Granton”, but the film deftly ties this to the novel’s “Memories of Matty” / “After the Burning” chapter, taking Matty’s attempts to win back his daughter’s love with the reckless gift of a kitten and substituting Tommy for Matty and the little girl for lost-love Lizzie. This is far more affecting an angle, in my view, especially when capped by Spud’s funereal rendition of “Two Little Boys”, which leaves Rolf Harris’s 1969 number one hit in the shade. Another big victory for the movie is its cast, and the harrowing yet hilarious performances that they each provide. It’s one thing to read about a character, and see him slowly take shape in your mind’s eye, but it’s quite another to have an actor the calibre of Ewan McGregor, Robert Carlyle or Ewen Bremner serve one up to you on a plate, his essence encapsulated in Danny Boyle’s perfectly-selected introductory anecdote and freeze-frame. The young McGregor gives a performance that I’ve never seen him top. Indeed, in the Blu-ray’s bonus material he admits that he took the role so seriously that he even toyed with the idea of trying heroin, which surely would have taken method acting to ad absurdum lengths. For all Renton’s obvious selfishness, apparently motiveless alienation and crippling apathy, McGregor forces you to like him. He makes you see his point of view. And not once do you think “That’s Obi-Wan Kenobi” (not a problem when the film was released, I’ll grant you, but it’s a hell of one now).

Oddly, the film’s most obvious departure from Welsh’s work makes the easiest transition across the media. In the novel, it isn’t Tommy but Matty who dies so horribly, and whose funeral serves as a palpable memento mori to his surviving junky friends. What the film cleverly latches onto is the idea that Tommy – especially when he’s played so genuinely by future Rome star Kevin McKidd – is the instantly-recognisable straight, easygoing presence that you’ll find in even the most lawless parcel of rogues, whereas the novel’s Matty was a whining and obnoxious dickhead. In the book, Tommy does split from Lizzie, get on heroin and contract HIV, leading to the superlatively grim “Winter in West Granton”, but the film deftly ties this to the novel’s “Memories of Matty” / “After the Burning” chapter, taking Matty’s attempts to win back his daughter’s love with the reckless gift of a kitten and substituting Tommy for Matty and the little girl for lost-love Lizzie. This is far more affecting an angle, in my view, especially when capped by Spud’s funereal rendition of “Two Little Boys”, which leaves Rolf Harris’s 1969 number one hit in the shade. Another big victory for the movie is its cast, and the harrowing yet hilarious performances that they each provide. It’s one thing to read about a character, and see him slowly take shape in your mind’s eye, but it’s quite another to have an actor the calibre of Ewan McGregor, Robert Carlyle or Ewen Bremner serve one up to you on a plate, his essence encapsulated in Danny Boyle’s perfectly-selected introductory anecdote and freeze-frame. The young McGregor gives a performance that I’ve never seen him top. Indeed, in the Blu-ray’s bonus material he admits that he took the role so seriously that he even toyed with the idea of trying heroin, which surely would have taken method acting to ad absurdum lengths. For all Renton’s obvious selfishness, apparently motiveless alienation and crippling apathy, McGregor forces you to like him. He makes you see his point of view. And not once do you think “That’s Obi-Wan Kenobi” (not a problem when the film was released, I’ll grant you, but it’s a hell of one now).

For his part, Carlyle gives a performance so compelling that I can’t point to a better one on his CV, and his efforts are all the more remarkable as he is physically nothing like the Franco Begbie conjured up by Welsh’s writing. To me though, it doesn’t matter that the film’s Begbie is short and lithe, moustachioed and lank-haired, instead of buff and buzz cut, as even in the book “the myth of Begbie” perpetuated by his associates (the word ‘friends’ is too strong) far outstrips the man. It’s explicit in the text that he’s not the hard man he claims to be – über-fit Tommy’s given him a panelling inside a boxing ring, as many of the book’s characters often recall with fondness – but he is a fucking psychopath, and Carlyle’s casting emphasises this. The coldness of that gaze couldn’t ever be captured in prose.

For his part, Carlyle gives a performance so compelling that I can’t point to a better one on his CV, and his efforts are all the more remarkable as he is physically nothing like the Franco Begbie conjured up by Welsh’s writing. To me though, it doesn’t matter that the film’s Begbie is short and lithe, moustachioed and lank-haired, instead of buff and buzz cut, as even in the book “the myth of Begbie” perpetuated by his associates (the word ‘friends’ is too strong) far outstrips the man. It’s explicit in the text that he’s not the hard man he claims to be – über-fit Tommy’s given him a panelling inside a boxing ring, as many of the book’s characters often recall with fondness – but he is a fucking psychopath, and Carlyle’s casting emphasises this. The coldness of that gaze couldn’t ever be captured in prose.

The finest performance though is Bremner’s. Having accepted the role of Danny ‘Spud’ Murphy a little uneasily, having played the more prestigious main protagonist in the book’s stage play adaptation, he creates a ‘catboy’ that’s impossible to forget. Irrespective of what’s going on elsewhere, Spud is an endearing, vulnerable presence throughout, which is incredible when you consider that he’s playing not only a smack-head, but one who turns over people’s houses and robs record stores for a living (or living death, at least).

The finest performance though is Bremner’s. Having accepted the role of Danny ‘Spud’ Murphy a little uneasily, having played the more prestigious main protagonist in the book’s stage play adaptation, he creates a ‘catboy’ that’s impossible to forget. Irrespective of what’s going on elsewhere, Spud is an endearing, vulnerable presence throughout, which is incredible when you consider that he’s playing not only a smack-head, but one who turns over people’s houses and robs record stores for a living (or living death, at least).However, the film’s greatest triumph is its tranformation of the metaphorical to the literal. Despite its schemie world being painted in ubiquitous council grey, “colourful” is one of the most common adjectives that you’ll see thrown about in reviews of Welsh’s stories, and with a widescreen canvas to transfer those tales onto, Boyle decide to show every shade of that glorious colour visually. His film is alive with vivid greens, reds and burnt oranges that are only outdone by the pulsating, scene-setting soundtrack, which provides not only a fierce pulse for the scream if you want to go faster plotline, but also a temporal anchor for the audience, as it is through music alone that the characters progression through time is felt (though the events of both the book and film remain as hard to accurately date as a UNIT-era Doctor Who story). In the same vein, Boyle doesn’t always present events as they are, but as they’re perceived by his protagonists. His film walks a thin line between the thorny doldrums of reality and the surreal dreamscapes of smack and “cauld turkey”, though it isn’t afraid to push the envelope even in the character’s soberest moments. Just look at Renton’s on-screen misadventures on the first day of the Edinburgh Festival, which see him squeeze down a toilet into an underwater wonderland populated by everything from shat-out suppositories to undetonated mines. The squalor of the novel is certainly there, but there’s something disconcertingly wondrous too.

But for every terrifying turn, stunning shot and stirring sound, there’s a heavy price to pay. Jonny Lee Miller’s “jazz purist” Sick Boy fails to live up to his literary counterpart as, save for in his dark moment over “perr wee Dawn”’s cot, he’s pushed to the periphery. All of his key traits are there to be seen, only understated, and overshadowed. You just don’t get the same sense of obsession from him, be it with getting his hole or getting that next fix. By extension, Renton’s anger at his parents’ incessant extolling of his pimping junky friend’s virtues, all of which are borne of his “most serpently” silver tongue in the book, is nowhere to be seen on screen; all we have in its place are pleas to listen to the advice of the deranged Franco, whose elevated to a moral pedestal just because doesn’t touch the same “shite” as his the rest of his motley crew. This might sound like such a small thing, but when considered alongside the heavy issues touched on above, that in the book are constantly threatening to drag young Mark into the Renton family quagmire of misery, it often feels like the final stone or last straw.

But for every terrifying turn, stunning shot and stirring sound, there’s a heavy price to pay. Jonny Lee Miller’s “jazz purist” Sick Boy fails to live up to his literary counterpart as, save for in his dark moment over “perr wee Dawn”’s cot, he’s pushed to the periphery. All of his key traits are there to be seen, only understated, and overshadowed. You just don’t get the same sense of obsession from him, be it with getting his hole or getting that next fix. By extension, Renton’s anger at his parents’ incessant extolling of his pimping junky friend’s virtues, all of which are borne of his “most serpently” silver tongue in the book, is nowhere to be seen on screen; all we have in its place are pleas to listen to the advice of the deranged Franco, whose elevated to a moral pedestal just because doesn’t touch the same “shite” as his the rest of his motley crew. This might sound like such a small thing, but when considered alongside the heavy issues touched on above, that in the book are constantly threatening to drag young Mark into the Renton family quagmire of misery, it often feels like the final stone or last straw.

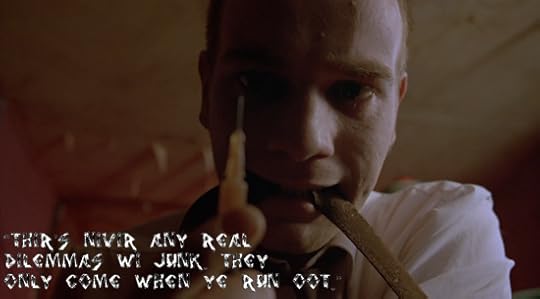

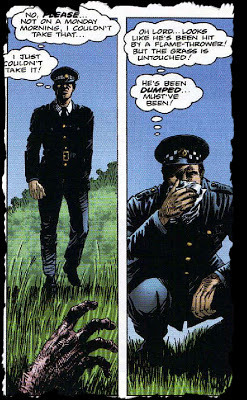

Worst of all though, Johnny Swan’s speech about having lost his leg in the Falklands (when in fact he damaged one of its main arteries when shooting up) was excluded, and even Renton’s trip to hospital to see him (see image, above) was left on the cutting room floor. “I was one of the lucky yins,” Johnny muses as he begs in the streets, his eyes glazing over as if he believes his own press. And when you think about it, he should. He was “one ay the lucky yins”…

Worst of all though, Johnny Swan’s speech about having lost his leg in the Falklands (when in fact he damaged one of its main arteries when shooting up) was excluded, and even Renton’s trip to hospital to see him (see image, above) was left on the cutting room floor. “I was one of the lucky yins,” Johnny muses as he begs in the streets, his eyes glazing over as if he believes his own press. And when you think about it, he should. He was “one ay the lucky yins”… “What yis up tae lads?

“What yis up tae lads? Trainspottin, eh?”

Danny Boyle’s movie did for motion pictures what Irvine Welsh’s novel did for literature, but I still have to give this one to the book. Not because it came first, or has more weight, or is even ‘better’ as a piece of entertainment. The novel is raw. It’s real; horrifyingly real. Why have a convention-adhering narrative? Life seldom does. It’s a mass of half-muddled anecdotes, myths and maybes; wanton digressions and capricious quirks. Why have a Matty and a Tommy, when just a Tommy would be more effective? Because that’s the sort of thing that happens. It’s not neat and it’s not tidy - it’s just like a pished old jakey staggering about in a decommissioned railway station, ironically labelling his estranged, sociopathic son and his skagboy mate a pair of trainspotters. Comical and random, but with a deep and terrifying lesson buried in it somewhere.

Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting novel is currently available in paperback (best price online today: £5.19 on Amazon) and digital formats (£3.99 from Amazon's Kindle Store or £5.49 from iTunes).

Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting movie is available from iTunes in 1080p HD for just £4.99, albeit without any extras. If you’re after bonus material too, the Ultimate Edition Blu-ray is available (best price online today: £6.75 on Amazon ).

Published on June 25, 2013 05:00

June 18, 2013

DVD Review | Doctor Who: The Mind of Evil

Published on June 18, 2013 04:36

June 6, 2013

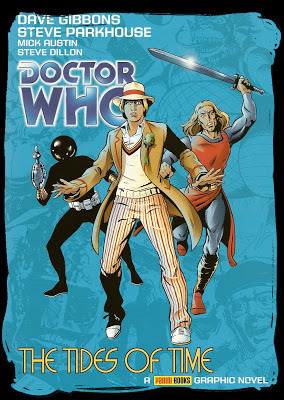

Beyond History’s End | 50th Anniversary Doctor Who Review 5 of 12 | The Tides of Time: The Complete Fifth Doctor Comic Strips written by Steve Parkhouse and illustrated by Dave Gibbons, Steve Parkhouse, Mick Austin and Steve Dillon

Most of my Beyond History’s End selections have required very little effort on my part. Since closing The History of the Doctor’s doors almost two years ago, there have been a flood of stories released across the media that I’ve been keen to talk – and invariably rave – about, most of them coming out of Big Finish Production’s incessant Who factory. However, determined not to let this fiftieth anniversary series turn into an ode to Big Finish, as is the obvious temptation, when it came to choosing the fifth Doctor’s story I decided to take a side-step into his often-overlooked adventures amidst the pages of Doctor Who Monthly, as collected together in Panini’s colossal 2005 volume, The Tides of Time.

Having heard its collective tales described as “Some of the greatest Doctor Who comic strips ever published”, I had high hopes for the heavy paperback – hopes raised even higher by two of the adventures’ Stockbridge setting. The quaint Hampshire village was used to astounding effect by Big Finish as the canvas for a trilogy of linked audio dramas in 2009, not to mention a stirring one-off instalment in 2006. My expectations were promptly dashed, however, as I soon found myself in a world that seemed to subscribe to the notion that Doctor Who is a kids’ show – and an exceedingly wacky one, at that.

Having heard its collective tales described as “Some of the greatest Doctor Who comic strips ever published”, I had high hopes for the heavy paperback – hopes raised even higher by two of the adventures’ Stockbridge setting. The quaint Hampshire village was used to astounding effect by Big Finish as the canvas for a trilogy of linked audio dramas in 2009, not to mention a stirring one-off instalment in 2006. My expectations were promptly dashed, however, as I soon found myself in a world that seemed to subscribe to the notion that Doctor Who is a kids’ show – and an exceedingly wacky one, at that.The anthology’s six-part title track is, admittedly, an incredible visual banquet, abounding with all manner of Dave Gibbons’ finest monstrosities and delights, which I imagine must have been even more liberating in their day, given the budgetary restraints that kept the television series’ writers’ imaginations in check back then. However, without context art is just art, and unfortunately the story that these enchanting pictures paint is not only bonkers, but bears little semblance to Doctor Who then or now.

The Doctor is a case in point. Save for his opening-scene batting and a passing resemblance to Peter Davison, there is nothing about this story’s Doctor that put me in mind of the series’ focal hero at all – a trend that regrettably extends across the whole volume. I recall writing reviews of stories in which I’ve felt that their Doctor was portrayed “generically”, but until now I’ve always meant that the Doctor in question could easily have been any of his incarnations - here I mean that he could be any quasi-scientific hero full stop. The Doctor’s world is arguably even more off-kilter – instead of the vice-ridden hegemony borne of Robert Holmes’ seminal Deadly Assassinscript and perpetuated by the Gallifreyspin-off and even recently-televised Who, this Gallifrey’s “Time-Lords”, with their laissez-faireapproach to hyphens, live inside the Matrix as “Matrix-Lords”, along with their Celestial Intervention Agency, and, apparently, Merlin. On occasion, this colourful, two-tone insanity does produce something fresh and exciting that works well within the Whoniverse as I know it, and especially so in the medium – take the removable-headed Gallifreyan construct Shayde, for instance –, but for the most part, it seems to shoot wide of the mark.

The Doctor is a case in point. Save for his opening-scene batting and a passing resemblance to Peter Davison, there is nothing about this story’s Doctor that put me in mind of the series’ focal hero at all – a trend that regrettably extends across the whole volume. I recall writing reviews of stories in which I’ve felt that their Doctor was portrayed “generically”, but until now I’ve always meant that the Doctor in question could easily have been any of his incarnations - here I mean that he could be any quasi-scientific hero full stop. The Doctor’s world is arguably even more off-kilter – instead of the vice-ridden hegemony borne of Robert Holmes’ seminal Deadly Assassinscript and perpetuated by the Gallifreyspin-off and even recently-televised Who, this Gallifrey’s “Time-Lords”, with their laissez-faireapproach to hyphens, live inside the Matrix as “Matrix-Lords”, along with their Celestial Intervention Agency, and, apparently, Merlin. On occasion, this colourful, two-tone insanity does produce something fresh and exciting that works well within the Whoniverse as I know it, and especially so in the medium – take the removable-headed Gallifreyan construct Shayde, for instance –, but for the most part, it seems to shoot wide of the mark.

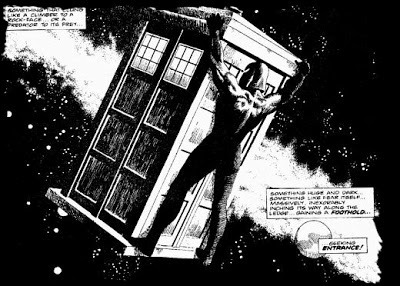

The Stockbridge strips, on the strength of which I’d purchased this volume, are much better, though my complaints about the Doctor’s dearth of distinguishing features stands in both. “Stars Fell on Stockbridge” is a lovely tale of the Doctor saving loveable misfit Maxwell Edison (sanssilver hammer), and vindicating his Mulderish existence into the bargain. Whilst even Dave Gibbons’ finest sketching couldn’t measure up to the amiable performance that movie star Mark Williams gave in The Eternal Summer, the story is so very poignant that, even as someone approaching the media-sprawling Stockbridge saga backwards, I was considerably buoyed going into “The Stockbridge Horror”, which is probably, on reflection, the collection’s finest offering. Steve Parkhouse’s sophisticated tale plays with temporally-twisted elements that would unwittingly sow the seeds of audios the calibre of Neverland and particularlyThe Fires of Vulcan. As far as I know, this strip boasts the Whoniverse’s first-ever battle TARDIS, and more notably still, throughout it boasts a level of implied horror that you’ll seldom find in any form Doctor Who, offsetting the juvenile vibes thatI got from “The Tides of Time”. Like an X-File ahead of its time, Parkhouse and Austin’s artwork never actually shows the dreadful images of immolation that the dialogue refers to, and on which the tale turns, but this only makes it play on the reader’s mind all the more.

The Stockbridge strips, on the strength of which I’d purchased this volume, are much better, though my complaints about the Doctor’s dearth of distinguishing features stands in both. “Stars Fell on Stockbridge” is a lovely tale of the Doctor saving loveable misfit Maxwell Edison (sanssilver hammer), and vindicating his Mulderish existence into the bargain. Whilst even Dave Gibbons’ finest sketching couldn’t measure up to the amiable performance that movie star Mark Williams gave in The Eternal Summer, the story is so very poignant that, even as someone approaching the media-sprawling Stockbridge saga backwards, I was considerably buoyed going into “The Stockbridge Horror”, which is probably, on reflection, the collection’s finest offering. Steve Parkhouse’s sophisticated tale plays with temporally-twisted elements that would unwittingly sow the seeds of audios the calibre of Neverland and particularlyThe Fires of Vulcan. As far as I know, this strip boasts the Whoniverse’s first-ever battle TARDIS, and more notably still, throughout it boasts a level of implied horror that you’ll seldom find in any form Doctor Who, offsetting the juvenile vibes thatI got from “The Tides of Time”. Like an X-File ahead of its time, Parkhouse and Austin’s artwork never actually shows the dreadful images of immolation that the dialogue refers to, and on which the tale turns, but this only makes it play on the reader’s mind all the more.

It’s downhill from there though, as the next two stories descend into utter anarchy. With the stalwart Steve Parkhouse leaving for bigger and better things, Mick Austin takes sole responsibility for the artwork, bringing with him a slightly surreal style that, whilst perfectly in keeping with the tone of the adventures, does little to aid their penetrability. “Lunar Lagoon” makes “The Tides of Time” seem straightforward, deliberately blurring the lines between ally and antagonist as well as one timeline and another, while “4-Dimensional Vistas” just blurs everything, pitting the Doctor and his newfound ally Gus against the interesting pairing of the Monk and the Ice Warriors. I desperately wanted to like both strips, as each contain elements that I think are inspired, but I struggled to follow either.

It’s downhill from there though, as the next two stories descend into utter anarchy. With the stalwart Steve Parkhouse leaving for bigger and better things, Mick Austin takes sole responsibility for the artwork, bringing with him a slightly surreal style that, whilst perfectly in keeping with the tone of the adventures, does little to aid their penetrability. “Lunar Lagoon” makes “The Tides of Time” seem straightforward, deliberately blurring the lines between ally and antagonist as well as one timeline and another, while “4-Dimensional Vistas” just blurs everything, pitting the Doctor and his newfound ally Gus against the interesting pairing of the Monk and the Ice Warriors. I desperately wanted to like both strips, as each contain elements that I think are inspired, but I struggled to follow either. The final fifth Doctor strip, “The Moderator”, is more successful. Save for “The Stockbridge Horror”, it has the most adult tone of all the stories in the anthology - a feeling exacerbated by Steve Dillon’s spikier illustrative style. The villain of the piece, the frog-like mogul Dogbolter, is an especially magnificent creation, particularly in this medium and particularly in an era of rampant Thatcherism. The volume is then capped, rather abnormally, with a fourth Doctor strip of questionable relevance but fair spirit, bringing The Tides of Time to a discordant finish that somehow feels oddly appropriate.

The final fifth Doctor strip, “The Moderator”, is more successful. Save for “The Stockbridge Horror”, it has the most adult tone of all the stories in the anthology - a feeling exacerbated by Steve Dillon’s spikier illustrative style. The villain of the piece, the frog-like mogul Dogbolter, is an especially magnificent creation, particularly in this medium and particularly in an era of rampant Thatcherism. The volume is then capped, rather abnormally, with a fourth Doctor strip of questionable relevance but fair spirit, bringing The Tides of Time to a discordant finish that somehow feels oddly appropriate.Overall then, my fifth trip Beyond History’s Endhas been the most disappointing. I had assumed that Big Finish’s Stockbridge stories had shown me only the top of the proverbial iceberg, and that these evidently-inspirational strips lurked below like some great clandestine masterpiece. In the event, it seems that the Big Finish stories cherry-picked the most successful element of the fifth Doctor’s DWM run, leaving the confusing and contradictory remnants festering frozen below water, where I wish I’d have left them.

The Tides of Time: The Complete Fifth Doctor Comic Strips is available in paperback from Panini. The cheapest online retailer today is Amazon, who are selling it for £9.67 with free super saver delivery.

It's been a year since Philippa ‘Flip’ Jackson found herself transported by Tube train to battle robot mosquitoes on a bizarre alien planet in the company of a Time Lord known only as 'the Doctor’. Lightning never strikes twice, they say. Only now there’s a flying saucer whooshing over the top of the night bus taking her home. Inside: the Doctor, with another extraterrestrial menace on his tail – the Daleks, and their twisted creator Davros! But while Flip and the fugitive Doctor struggle to beat back the Daleks’ incursion into 21st century London, Davros’s real plan is taking shape nearly 200 years in the past, on the other side of the English Channel. At the battle of Waterloo...

Read retro Doctor Who reviews @

Published on June 06, 2013 04:36

June 4, 2013

Star Wars LEGO Review | 75005 Rancor Pit

Modular designs are now commonly found in most LEGO themes. From the soaring multi-storey pet shops and period fire stations of City to the set-sprawling schools of witchcraft and wizardry of Harry Potter, LEGO models are now more compatible than ever before, making purchases such as the overpriced but irresistible Rancor Pit set mandatory for Force-sensitive builders everywhere.

The set’s greatest attraction is without doubt its titular Rancor creature, who outdoes even impressive offerings like the Wampa when it comes to detail and playability. The ten-centimetre tall monstrosity has jaws that open and shut, allowing its minifigure-prey to hang limp out of its mouth, and its individually-removable claws can be broken off when it’s lost in the reckless zeal of bloodlust. With a broken shackle hanging from one hand and an ill-fated Gamorrean guard clasped in the other, all this megafigure is missing is the stop-motion slaver that burned Return of the Jedi’s subterranean set piece into the minds of two generations’ moviegoers.

The set’s greatest attraction is without doubt its titular Rancor creature, who outdoes even impressive offerings like the Wampa when it comes to detail and playability. The ten-centimetre tall monstrosity has jaws that open and shut, allowing its minifigure-prey to hang limp out of its mouth, and its individually-removable claws can be broken off when it’s lost in the reckless zeal of bloodlust. With a broken shackle hanging from one hand and an ill-fated Gamorrean guard clasped in the other, all this megafigure is missing is the stop-motion slaver that burned Return of the Jedi’s subterranean set piece into the minds of two generations’ moviegoers.

The rest of the set’s minifigures really are mini in comparison, but it’s still quite apparent that the Rancor is significantly smaller than it would have been had it been accurately produced to scale. However, as the proud owner of a trilogy-spanning Death Star that has fewer rooms than my house and an open-plan Millennium Falcon that only has room for one in its cockpit, it would be a little churlish of me to grumble too much about issues of sizing – particularly when both the Gamorrean (who’s an exact replica of his colleague thrown in with the Jabba’s Palace set, albeit brandishing a drumstick here instead of an axe) and Malakili are such charming little fellows. I’m especially fond of the latter, as LEGO have captured absolutely the character’s defining hang-dog, “You’ve just killed my pet!” expression, if not his wobbling rolls of fat. In contrast, the blonde and conservative Luke Skywalker doesn’t really measure up. The bone that he clutches in place of his lost lightsaber is certainly movie-accurate, but it would have been nice to have both, and his reversible head is a complete calamity as his hairpiece doesn’t cover his well-defined dimples – whichever mood you choose to fix him with, the poor lad’s got a chin on the back of his head.

The rest of the set’s minifigures really are mini in comparison, but it’s still quite apparent that the Rancor is significantly smaller than it would have been had it been accurately produced to scale. However, as the proud owner of a trilogy-spanning Death Star that has fewer rooms than my house and an open-plan Millennium Falcon that only has room for one in its cockpit, it would be a little churlish of me to grumble too much about issues of sizing – particularly when both the Gamorrean (who’s an exact replica of his colleague thrown in with the Jabba’s Palace set, albeit brandishing a drumstick here instead of an axe) and Malakili are such charming little fellows. I’m especially fond of the latter, as LEGO have captured absolutely the character’s defining hang-dog, “You’ve just killed my pet!” expression, if not his wobbling rolls of fat. In contrast, the blonde and conservative Luke Skywalker doesn’t really measure up. The bone that he clutches in place of his lost lightsaber is certainly movie-accurate, but it would have been nice to have both, and his reversible head is a complete calamity as his hairpiece doesn’t cover his well-defined dimples – whichever mood you choose to fix him with, the poor lad’s got a chin on the back of his head.

The pit itself matches the style of Jabba’s palace, and is fleshed out nicely with some deft flashes of finesse such as oversized keys and even festering skeletons. It’s far flimsier though, with only its gate-holding wall complete and its base and roof absent. For those that own it, the latter can be provided by the main body of the Hutt gangster’s palatial gaffe, which rests nicely upon the four small pyramids that crown the pit, but it’s worth noting that the palace’s tower annex, which can be (and invariably is, in mine’s case) connected to the throne room via a handful of interlocking pieces, cannot be attached so readily, despite what the picture on the back of the box implies. Unless you’ve a load of spare sand, grey and brown-coloured bricks, the best that you can hope for is to nestle the tower in next to the rest of the structure, and hope for the best.

The pit itself matches the style of Jabba’s palace, and is fleshed out nicely with some deft flashes of finesse such as oversized keys and even festering skeletons. It’s far flimsier though, with only its gate-holding wall complete and its base and roof absent. For those that own it, the latter can be provided by the main body of the Hutt gangster’s palatial gaffe, which rests nicely upon the four small pyramids that crown the pit, but it’s worth noting that the palace’s tower annex, which can be (and invariably is, in mine’s case) connected to the throne room via a handful of interlocking pieces, cannot be attached so readily, despite what the picture on the back of the box implies. Unless you’ve a load of spare sand, grey and brown-coloured bricks, the best that you can hope for is to nestle the tower in next to the rest of the structure, and hope for the best.

Ultimately though, any gripes that I had about this set instantly evaporated the very first time that I sent young Skywalker plummeting through Jabba’s trapdoor into the pit waiting below. Admittedly, £59.99 – a cost pulled into sharp focus by the entire saga’s Blu-rays’ going rate online - is a lofty price to pay for such a juvenile pleasure, but I dare say that if you’re interested enough in this set to have read this review, you won’t begrudge a penny of it. The Star Wars LEGO Rancor Pit is available from LEGO directly for £59.99 with free delivery. Today's cheapest online retailer though is ASDA Direct, who are currently selling this set for £47.99 plus £2.95 delivery (£50.94 overall).

Ultimately though, any gripes that I had about this set instantly evaporated the very first time that I sent young Skywalker plummeting through Jabba’s trapdoor into the pit waiting below. Admittedly, £59.99 – a cost pulled into sharp focus by the entire saga’s Blu-rays’ going rate online - is a lofty price to pay for such a juvenile pleasure, but I dare say that if you’re interested enough in this set to have read this review, you won’t begrudge a penny of it. The Star Wars LEGO Rancor Pit is available from LEGO directly for £59.99 with free delivery. Today's cheapest online retailer though is ASDA Direct, who are currently selling this set for £47.99 plus £2.95 delivery (£50.94 overall).

The set’s greatest attraction is without doubt its titular Rancor creature, who outdoes even impressive offerings like the Wampa when it comes to detail and playability. The ten-centimetre tall monstrosity has jaws that open and shut, allowing its minifigure-prey to hang limp out of its mouth, and its individually-removable claws can be broken off when it’s lost in the reckless zeal of bloodlust. With a broken shackle hanging from one hand and an ill-fated Gamorrean guard clasped in the other, all this megafigure is missing is the stop-motion slaver that burned Return of the Jedi’s subterranean set piece into the minds of two generations’ moviegoers.

The set’s greatest attraction is without doubt its titular Rancor creature, who outdoes even impressive offerings like the Wampa when it comes to detail and playability. The ten-centimetre tall monstrosity has jaws that open and shut, allowing its minifigure-prey to hang limp out of its mouth, and its individually-removable claws can be broken off when it’s lost in the reckless zeal of bloodlust. With a broken shackle hanging from one hand and an ill-fated Gamorrean guard clasped in the other, all this megafigure is missing is the stop-motion slaver that burned Return of the Jedi’s subterranean set piece into the minds of two generations’ moviegoers. The rest of the set’s minifigures really are mini in comparison, but it’s still quite apparent that the Rancor is significantly smaller than it would have been had it been accurately produced to scale. However, as the proud owner of a trilogy-spanning Death Star that has fewer rooms than my house and an open-plan Millennium Falcon that only has room for one in its cockpit, it would be a little churlish of me to grumble too much about issues of sizing – particularly when both the Gamorrean (who’s an exact replica of his colleague thrown in with the Jabba’s Palace set, albeit brandishing a drumstick here instead of an axe) and Malakili are such charming little fellows. I’m especially fond of the latter, as LEGO have captured absolutely the character’s defining hang-dog, “You’ve just killed my pet!” expression, if not his wobbling rolls of fat. In contrast, the blonde and conservative Luke Skywalker doesn’t really measure up. The bone that he clutches in place of his lost lightsaber is certainly movie-accurate, but it would have been nice to have both, and his reversible head is a complete calamity as his hairpiece doesn’t cover his well-defined dimples – whichever mood you choose to fix him with, the poor lad’s got a chin on the back of his head.

The rest of the set’s minifigures really are mini in comparison, but it’s still quite apparent that the Rancor is significantly smaller than it would have been had it been accurately produced to scale. However, as the proud owner of a trilogy-spanning Death Star that has fewer rooms than my house and an open-plan Millennium Falcon that only has room for one in its cockpit, it would be a little churlish of me to grumble too much about issues of sizing – particularly when both the Gamorrean (who’s an exact replica of his colleague thrown in with the Jabba’s Palace set, albeit brandishing a drumstick here instead of an axe) and Malakili are such charming little fellows. I’m especially fond of the latter, as LEGO have captured absolutely the character’s defining hang-dog, “You’ve just killed my pet!” expression, if not his wobbling rolls of fat. In contrast, the blonde and conservative Luke Skywalker doesn’t really measure up. The bone that he clutches in place of his lost lightsaber is certainly movie-accurate, but it would have been nice to have both, and his reversible head is a complete calamity as his hairpiece doesn’t cover his well-defined dimples – whichever mood you choose to fix him with, the poor lad’s got a chin on the back of his head.

The pit itself matches the style of Jabba’s palace, and is fleshed out nicely with some deft flashes of finesse such as oversized keys and even festering skeletons. It’s far flimsier though, with only its gate-holding wall complete and its base and roof absent. For those that own it, the latter can be provided by the main body of the Hutt gangster’s palatial gaffe, which rests nicely upon the four small pyramids that crown the pit, but it’s worth noting that the palace’s tower annex, which can be (and invariably is, in mine’s case) connected to the throne room via a handful of interlocking pieces, cannot be attached so readily, despite what the picture on the back of the box implies. Unless you’ve a load of spare sand, grey and brown-coloured bricks, the best that you can hope for is to nestle the tower in next to the rest of the structure, and hope for the best.

The pit itself matches the style of Jabba’s palace, and is fleshed out nicely with some deft flashes of finesse such as oversized keys and even festering skeletons. It’s far flimsier though, with only its gate-holding wall complete and its base and roof absent. For those that own it, the latter can be provided by the main body of the Hutt gangster’s palatial gaffe, which rests nicely upon the four small pyramids that crown the pit, but it’s worth noting that the palace’s tower annex, which can be (and invariably is, in mine’s case) connected to the throne room via a handful of interlocking pieces, cannot be attached so readily, despite what the picture on the back of the box implies. Unless you’ve a load of spare sand, grey and brown-coloured bricks, the best that you can hope for is to nestle the tower in next to the rest of the structure, and hope for the best.

Ultimately though, any gripes that I had about this set instantly evaporated the very first time that I sent young Skywalker plummeting through Jabba’s trapdoor into the pit waiting below. Admittedly, £59.99 – a cost pulled into sharp focus by the entire saga’s Blu-rays’ going rate online - is a lofty price to pay for such a juvenile pleasure, but I dare say that if you’re interested enough in this set to have read this review, you won’t begrudge a penny of it. The Star Wars LEGO Rancor Pit is available from LEGO directly for £59.99 with free delivery. Today's cheapest online retailer though is ASDA Direct, who are currently selling this set for £47.99 plus £2.95 delivery (£50.94 overall).

Ultimately though, any gripes that I had about this set instantly evaporated the very first time that I sent young Skywalker plummeting through Jabba’s trapdoor into the pit waiting below. Admittedly, £59.99 – a cost pulled into sharp focus by the entire saga’s Blu-rays’ going rate online - is a lofty price to pay for such a juvenile pleasure, but I dare say that if you’re interested enough in this set to have read this review, you won’t begrudge a penny of it. The Star Wars LEGO Rancor Pit is available from LEGO directly for £59.99 with free delivery. Today's cheapest online retailer though is ASDA Direct, who are currently selling this set for £47.99 plus £2.95 delivery (£50.94 overall).

Published on June 04, 2013 04:17

May 28, 2013

Book Review | Skagboys by Irvine Welsh

If you’re one of the many who ‘got’ Trainspotting,as I did, then you probably laud it as one of the greatest works of fiction ever to come out of Great Britain. Irvine Welsh’s many offerings since have, for the most part, retained its raw and uncompromising style, and on occasion the great Scot has pushed the envelope even further, blurring the lines between contemporary urban tales and science fiction; even between his idiosyncratic Leith lingo and his hitherto seldom-seen RP prose. But despite the evident distinction of almost all his subsequent works, until Skagboys came along there wasn’t a single title in the Welsh canon that approached his first book in terms of significance. And I didn’t expect that there ever would be; after all, you can’t open Pandora’s box twice, can you?

Well, apparently you can.

Well, apparently you can.

A study in contrasts, Skagboys (or “The Junky and the Incest Victim”, as I’d love to have seen it subtitled) maintains every gram of Trainspotting’s sledgehammer squalor, but complements it with the thoughtful eloquence that has insidiously blossomed inside Welsh’s writing as the years have worn on. Rather than debase the piece, this articulacy only serves to heighten the unstoppable tragedy of it, as through its focal character’s notebook musings we truly appreciate just how far he is falling – and how fast. The aching abyss between the proud, politicised first-class university student seen in the events of “Concerning Orgreave” and the ubiquitously-dysfunctional collection tin-chorrier that bleeds into Trainspotting couldn’t possibly be any wider or deeper. For all Welsh’s even, honest and occasionally rapturous depiction of heroin, the image left lingering by Skagboys is that of two mute, humourless and Valium-fuelled orang-utans setting out into the night in search of a fix; not even ghosts of the flawed but vibrant inbetweeners of the novel’s start.

“Ah didnae ask tae live n ah’m no feart tae die. Aw that’ll happen is that it’ll be like before ah wis alive; it couldnae have been that great, but it wisnae that shite either, or ah’d have minded aboot it. Ah was just here tae get ma fuckin records.”