E.G. Wolverson's Blog, page 17

October 26, 2013

Book Review | Star Trek: Typhon Pact – The Struggle Within by Christopher L Bennett

The United Federation of Planets’ expansion of the Khitomer Accords is, in many respects, significantly less surprising than Pocket Books’ extension of its Star Trek: Typhon Pact saga beyond its initial four-book run. Whilst I thoroughly enjoyed two of them, and quite liked another, general reaction was considerably more mixed, with many readers lamenting the arc’s languorous pace and failure to capitalise upon the potential of the Pact’s hitherto-uncharted societies, such as the Holy Order of the Kinshaya and the Tzenkethi Coalition. It’s ironic, then, that an almost afterthought of an e-book not only sets the storyline off on its finish push towards climax, but also sates much of the hunger that the initial run left unsatisfied.

In part an unlikely sequel to the 1990 TNGepisode “Suddenly Human”, Christopher L Bennett’s novella sees the Enterprise visit Talar, where Jono – the young man raised by the Talarians following the death of his human parents – has grown into a diplomat of some note, and is now assisting his adoptive father, Endar, to negotiate an alliance with the Federation that it is hoped will strengthen both in the face of mounting Typhon Pact antagonism. However, through they mirror the traditional veiling customs of the Middle East more closely than they do, say, calculatedly oppressive Ferengi practices, Talarian attitudes towards females don’t sit well with Federation ideology. A group of militant freedom fighters decide to take advantage of this, as well as the Federation’s famous championing of freedom of expression, by using the Enterprise’s visit to mount an attack Talar’s patriarchy under the cover of a peaceful demonstration, kidnapping Dr Crusher in the process and leaving her husband and captain in the conflicted position of having to weigh the mother of his son’s life and the Federation’s desperate need of an ally against not only his strong views on Starfleet’s deep-rooted non-interference doctrine, but also his personal sympathy for the women of Talar’s cause, if not their methods. Meanwhile, T’Ryssa Chen and Jasminder Choudhury, the next generation of Next Generation bridge officers, are recruited by Starfleet Intelligence to go undercover on Kinshaya. There they are to pose as Romulan members of Spock’s Unification movement who are visiting the world to show their support for the under-heel Kinshayan masses, with a view to helping them to foment rebellion, and perhaps even bring about a regime change that could tip the delicate balance of power within the Pact in favour of those less aggressive towards the Federation.

In part an unlikely sequel to the 1990 TNGepisode “Suddenly Human”, Christopher L Bennett’s novella sees the Enterprise visit Talar, where Jono – the young man raised by the Talarians following the death of his human parents – has grown into a diplomat of some note, and is now assisting his adoptive father, Endar, to negotiate an alliance with the Federation that it is hoped will strengthen both in the face of mounting Typhon Pact antagonism. However, through they mirror the traditional veiling customs of the Middle East more closely than they do, say, calculatedly oppressive Ferengi practices, Talarian attitudes towards females don’t sit well with Federation ideology. A group of militant freedom fighters decide to take advantage of this, as well as the Federation’s famous championing of freedom of expression, by using the Enterprise’s visit to mount an attack Talar’s patriarchy under the cover of a peaceful demonstration, kidnapping Dr Crusher in the process and leaving her husband and captain in the conflicted position of having to weigh the mother of his son’s life and the Federation’s desperate need of an ally against not only his strong views on Starfleet’s deep-rooted non-interference doctrine, but also his personal sympathy for the women of Talar’s cause, if not their methods. Meanwhile, T’Ryssa Chen and Jasminder Choudhury, the next generation of Next Generation bridge officers, are recruited by Starfleet Intelligence to go undercover on Kinshaya. There they are to pose as Romulan members of Spock’s Unification movement who are visiting the world to show their support for the under-heel Kinshayan masses, with a view to helping them to foment rebellion, and perhaps even bring about a regime change that could tip the delicate balance of power within the Pact in favour of those less aggressive towards the Federation.

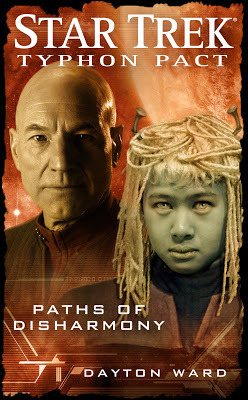

The Enterprise half of the story is an impressive and intricate tapestry of both welcome fan service and clever, careful storytelling. Its “Suddenly Human” heritage is something of a red herring for readers as, save for Jono’s unique pedigree playing a hand in the conclusive events of the story, the events on Talar could easily have unfolded on any non-aligned planet. The real meat of its drama turns upon how Picard balances his duties as captain – essentially his duty to his conscience – against his personal responsibilities as a husband and father. Ever the remote bachelor on television, Captain Picard’s never had to struggle against his feelings in the way that he does here, and he can’t even rely upon his first officer’s counsel to help shape his decision as the otherwise-redoubtable Commander Worf has a solitary black mark on his own service record, earned through his deliberate dereliction of duty when trying to save his own wife’s life whilst posted to Deep Space Nine during the Dominion War. It’s an enthralling read in every respect, and, like Paths of Disharmony before it, both bold and surprising in its resolution.

Bennett also uses the Talar storyline to finally take a more detailed look at the elusive Tzenkethi, further fleshing out the basics of their form and examining the history of their species as it is understood by other races. A species of matchless ethereal beauty, the once-fragile Tzenkethi were long exploited as “novelties and slaves”, eventually driving them to turn inwards, closing their borders and even going so far as to edit their own genomes to instil an innate loathing of offworlders – their newfound Typhon Pact friends included, towards whom they feel little but paranoia and a fanatical need to control. Unfortunately the nature of the Tzenkethi involvement in the plot and the brevity of the piece conspire to keep them in the wings here, but it’s nonetheless a testament to Bennett’s skill that he’s able to convey more through one well-written character appearing in just a few fleeting chapters than had been done across the whole media spectrum previously. The Kinshaya, conversely, are explored in immense detail by the author, who seems to share T’Ryssa’s enthusiasm for the race. As the Enterprise’s unconventional contact officer so succinctly sums up, “They’re basically griffins… xenophobic, isolationist religious fanatics, but still, griffins!”

“I know, I know. It’s like they teach us in Prime Directive 101: A cultural change doesn’t really take hold unless it comes from within.” Jasminder smiled. “Nor does a personal one.”

In his acknowledgements, Bennett tellingly dedicates The Struggle Within to “the courageous resistance movement in Egypt, whose members provided that nonviolent action can achieve what violence cannot,” and these sentiments are keenly felt in the Kinshayan limb of his narrative, which serves as inspiring counterbalance to the women of Talar’s violent deeds. But the mission to Kinshaya is as much a sabbatical for Jasminder as it is an intelligence operation, as the once-serene Denevan looks to put the destruction of her world and the comfort that she’s since found in aggression – and, by extension, the arms of Worf – behind her. But shaving her head and adorning it with Romulan mourning tattoos, á la Eric Bana’s Nero, isn’t nearly enough to help her bury the past and find her centre again – for that, she needs the company of the Enterprise-E’s loveable and exuberant half-human, half-Vulcan Spock antithesis, who has to suffer like she has never done before her commanding officer and friend can find herself anew.

In his acknowledgements, Bennett tellingly dedicates The Struggle Within to “the courageous resistance movement in Egypt, whose members provided that nonviolent action can achieve what violence cannot,” and these sentiments are keenly felt in the Kinshayan limb of his narrative, which serves as inspiring counterbalance to the women of Talar’s violent deeds. But the mission to Kinshaya is as much a sabbatical for Jasminder as it is an intelligence operation, as the once-serene Denevan looks to put the destruction of her world and the comfort that she’s since found in aggression – and, by extension, the arms of Worf – behind her. But shaving her head and adorning it with Romulan mourning tattoos, á la Eric Bana’s Nero, isn’t nearly enough to help her bury the past and find her centre again – for that, she needs the company of the Enterprise-E’s loveable and exuberant half-human, half-Vulcan Spock antithesis, who has to suffer like she has never done before her commanding officer and friend can find herself anew.

But the most wonderful thing about this book isn’t its deft handling of action, intrigue, or even character. It’s most outstanding quality is that it feels exactly like an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation – or, at least, an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Next Generation. The limited word count of the piece instils the sort of pace that the television series used to deliver on a weekly basis, even mirroring the two-thread narrative structure invariably found in most stories. The only things that set The Struggle Within apart from a bona fide TV episode are its heavily-featured non-humanoid contingent (that even TNG’s budget probably wouldn’t have convincingly stretched to realising on screen), and its heavy grounding in post-Nemesisarcs, both of which I feel add to rather than detract from the piece in any event. If you’ve a TNG itch that needs scratching, but find that time or funds are in short supply, then you could do a hell of a lot worse than throw a few pounds at The Struggle Within – without a doubt Star Trek: Typhon Pact’s finest hour. The Struggle Within is currently available only as an e-book (£4.41 from Amazon’s KindleStore or £4.49 from iTunes).

In part an unlikely sequel to the 1990 TNGepisode “Suddenly Human”, Christopher L Bennett’s novella sees the Enterprise visit Talar, where Jono – the young man raised by the Talarians following the death of his human parents – has grown into a diplomat of some note, and is now assisting his adoptive father, Endar, to negotiate an alliance with the Federation that it is hoped will strengthen both in the face of mounting Typhon Pact antagonism. However, through they mirror the traditional veiling customs of the Middle East more closely than they do, say, calculatedly oppressive Ferengi practices, Talarian attitudes towards females don’t sit well with Federation ideology. A group of militant freedom fighters decide to take advantage of this, as well as the Federation’s famous championing of freedom of expression, by using the Enterprise’s visit to mount an attack Talar’s patriarchy under the cover of a peaceful demonstration, kidnapping Dr Crusher in the process and leaving her husband and captain in the conflicted position of having to weigh the mother of his son’s life and the Federation’s desperate need of an ally against not only his strong views on Starfleet’s deep-rooted non-interference doctrine, but also his personal sympathy for the women of Talar’s cause, if not their methods. Meanwhile, T’Ryssa Chen and Jasminder Choudhury, the next generation of Next Generation bridge officers, are recruited by Starfleet Intelligence to go undercover on Kinshaya. There they are to pose as Romulan members of Spock’s Unification movement who are visiting the world to show their support for the under-heel Kinshayan masses, with a view to helping them to foment rebellion, and perhaps even bring about a regime change that could tip the delicate balance of power within the Pact in favour of those less aggressive towards the Federation.

In part an unlikely sequel to the 1990 TNGepisode “Suddenly Human”, Christopher L Bennett’s novella sees the Enterprise visit Talar, where Jono – the young man raised by the Talarians following the death of his human parents – has grown into a diplomat of some note, and is now assisting his adoptive father, Endar, to negotiate an alliance with the Federation that it is hoped will strengthen both in the face of mounting Typhon Pact antagonism. However, through they mirror the traditional veiling customs of the Middle East more closely than they do, say, calculatedly oppressive Ferengi practices, Talarian attitudes towards females don’t sit well with Federation ideology. A group of militant freedom fighters decide to take advantage of this, as well as the Federation’s famous championing of freedom of expression, by using the Enterprise’s visit to mount an attack Talar’s patriarchy under the cover of a peaceful demonstration, kidnapping Dr Crusher in the process and leaving her husband and captain in the conflicted position of having to weigh the mother of his son’s life and the Federation’s desperate need of an ally against not only his strong views on Starfleet’s deep-rooted non-interference doctrine, but also his personal sympathy for the women of Talar’s cause, if not their methods. Meanwhile, T’Ryssa Chen and Jasminder Choudhury, the next generation of Next Generation bridge officers, are recruited by Starfleet Intelligence to go undercover on Kinshaya. There they are to pose as Romulan members of Spock’s Unification movement who are visiting the world to show their support for the under-heel Kinshayan masses, with a view to helping them to foment rebellion, and perhaps even bring about a regime change that could tip the delicate balance of power within the Pact in favour of those less aggressive towards the Federation.The Enterprise half of the story is an impressive and intricate tapestry of both welcome fan service and clever, careful storytelling. Its “Suddenly Human” heritage is something of a red herring for readers as, save for Jono’s unique pedigree playing a hand in the conclusive events of the story, the events on Talar could easily have unfolded on any non-aligned planet. The real meat of its drama turns upon how Picard balances his duties as captain – essentially his duty to his conscience – against his personal responsibilities as a husband and father. Ever the remote bachelor on television, Captain Picard’s never had to struggle against his feelings in the way that he does here, and he can’t even rely upon his first officer’s counsel to help shape his decision as the otherwise-redoubtable Commander Worf has a solitary black mark on his own service record, earned through his deliberate dereliction of duty when trying to save his own wife’s life whilst posted to Deep Space Nine during the Dominion War. It’s an enthralling read in every respect, and, like Paths of Disharmony before it, both bold and surprising in its resolution.

Bennett also uses the Talar storyline to finally take a more detailed look at the elusive Tzenkethi, further fleshing out the basics of their form and examining the history of their species as it is understood by other races. A species of matchless ethereal beauty, the once-fragile Tzenkethi were long exploited as “novelties and slaves”, eventually driving them to turn inwards, closing their borders and even going so far as to edit their own genomes to instil an innate loathing of offworlders – their newfound Typhon Pact friends included, towards whom they feel little but paranoia and a fanatical need to control. Unfortunately the nature of the Tzenkethi involvement in the plot and the brevity of the piece conspire to keep them in the wings here, but it’s nonetheless a testament to Bennett’s skill that he’s able to convey more through one well-written character appearing in just a few fleeting chapters than had been done across the whole media spectrum previously. The Kinshaya, conversely, are explored in immense detail by the author, who seems to share T’Ryssa’s enthusiasm for the race. As the Enterprise’s unconventional contact officer so succinctly sums up, “They’re basically griffins… xenophobic, isolationist religious fanatics, but still, griffins!”

“I know, I know. It’s like they teach us in Prime Directive 101: A cultural change doesn’t really take hold unless it comes from within.” Jasminder smiled. “Nor does a personal one.”

In his acknowledgements, Bennett tellingly dedicates The Struggle Within to “the courageous resistance movement in Egypt, whose members provided that nonviolent action can achieve what violence cannot,” and these sentiments are keenly felt in the Kinshayan limb of his narrative, which serves as inspiring counterbalance to the women of Talar’s violent deeds. But the mission to Kinshaya is as much a sabbatical for Jasminder as it is an intelligence operation, as the once-serene Denevan looks to put the destruction of her world and the comfort that she’s since found in aggression – and, by extension, the arms of Worf – behind her. But shaving her head and adorning it with Romulan mourning tattoos, á la Eric Bana’s Nero, isn’t nearly enough to help her bury the past and find her centre again – for that, she needs the company of the Enterprise-E’s loveable and exuberant half-human, half-Vulcan Spock antithesis, who has to suffer like she has never done before her commanding officer and friend can find herself anew.

In his acknowledgements, Bennett tellingly dedicates The Struggle Within to “the courageous resistance movement in Egypt, whose members provided that nonviolent action can achieve what violence cannot,” and these sentiments are keenly felt in the Kinshayan limb of his narrative, which serves as inspiring counterbalance to the women of Talar’s violent deeds. But the mission to Kinshaya is as much a sabbatical for Jasminder as it is an intelligence operation, as the once-serene Denevan looks to put the destruction of her world and the comfort that she’s since found in aggression – and, by extension, the arms of Worf – behind her. But shaving her head and adorning it with Romulan mourning tattoos, á la Eric Bana’s Nero, isn’t nearly enough to help her bury the past and find her centre again – for that, she needs the company of the Enterprise-E’s loveable and exuberant half-human, half-Vulcan Spock antithesis, who has to suffer like she has never done before her commanding officer and friend can find herself anew.But the most wonderful thing about this book isn’t its deft handling of action, intrigue, or even character. It’s most outstanding quality is that it feels exactly like an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation – or, at least, an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Next Generation. The limited word count of the piece instils the sort of pace that the television series used to deliver on a weekly basis, even mirroring the two-thread narrative structure invariably found in most stories. The only things that set The Struggle Within apart from a bona fide TV episode are its heavily-featured non-humanoid contingent (that even TNG’s budget probably wouldn’t have convincingly stretched to realising on screen), and its heavy grounding in post-Nemesisarcs, both of which I feel add to rather than detract from the piece in any event. If you’ve a TNG itch that needs scratching, but find that time or funds are in short supply, then you could do a hell of a lot worse than throw a few pounds at The Struggle Within – without a doubt Star Trek: Typhon Pact’s finest hour. The Struggle Within is currently available only as an e-book (£4.41 from Amazon’s KindleStore or £4.49 from iTunes).

Published on October 26, 2013 10:41

October 6, 2013

DVD Review | Doctor Who: Scream of the Shalka

Published on October 06, 2013 08:42

October 1, 2013

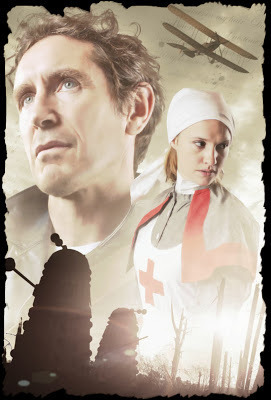

Beyond History's End | 50th Anniversary Doctor Who Review 8 of 12 | Dark Eyes written by Nicholas Briggs

There have been a lot of Big Finish specials over the years – so many, in fact, that they’ve retrospectively been carved up by the company, with ex-subscriber-exclusive ‘bonus releases’ now occupying their own corner of the site, and commercial specials another. But of them all, Dark Eyes feels like the most special. Like UNIT: Dominion before it, it takes the form of four linked, yet individually-packaged, episodes held together by a stylish cardboard slipcase, but Dark Eyes’ specialness extends far beyond its shelf appeal.

Since he first morphed to life part-way through the ill-fated Fox attempt at a Stateside Doctor Who pilot, Paul McGann’s Doctor has enjoyed more adventures across the media than any of his cohorts, and every single one of them that has bore his visage on its artwork has plucked his likeness from one the few images produced to promote that Fox movie, bar one: Dark Eyes. This box set’s artwork shows McGann’s once-Byronic embodiment of the Time Lord looking more like the incarnation that will eventually take his place at the TARDIS console. Brandishing a two-year old sonic screwdriver fashioned by the Weta Workshop and sporting a shorter hairstyle and a heavy leather jacket that scream ‘mariner’, if not ‘time warrior’, the images of the weathered eighth Doctor found adorning this special production make a bold statement about how the character has changed over the years, and indeed the changes soon to come.

More radically still, Dark Eyes subversively plays with listeners’ hopes and expectations through its subject matter, which sees the Time Lord Straxus (Human Resources, The Vengeance of Morbius) enlist the Doctor’s help to thwart an “insane plot to destroy the universe” – a plot that, it turns out, the Daleks are behind. Following soon in the wake of To the Death, in which the personal war between the Doctor and the Daleks plumbed agonising new depths, Dark Eyes enflames the feeling of inexorability already building, bringing Gallifrey right into the heart of the conflict and setting the stall for the inter-series showdown to come. Of course, in Martin Montague’s accompanying documentary, this story’s writer and BBC licensee Nicholas Briggs is quick to make it plain that Big Finish are not scouting the foothills to the Last Great Time War here, even going so far as to throw a cruel joke into his third episode to hammer his point home, but that is not how things sound to the listener. Every aspect of this production, from the Doctor’s intensifying grief and despair to the mounting temporal power of the Daleks and their time controller, points obviously towards the inevitable. Big Finish’s licence might not presently allow them to encroach upon ‘new’ Doctor Who or any of its formative angles, but they seem to have finally realised that there’s nothing stopping them from taking us far as Hitler invading Poland. In such context, Dark Eyes is just more hyperinflation.

The most special thing about Dark Eyes, though, is a little more subtle than a new hairdo or an old war don’t – it’s a question of form. Whereas UNIT: Dominion was consciously cinematic, but still retained the spirit of a traditional Doctor Who adventure, Dark Eyes is another “concept album” from Briggs, closer in structure and tone to one of his grim Dalek Empire epics than anything that Big Finish have previously put out under a Doctor Who banner. It is defined by incident, but carried by character. It is about hope, but abounding with despair. It’s a story that hones in on just two – perhaps three, if you’re prepared to stretch a point – people, and uses the explosions erupting all around them to dissect their souls.

The most special thing about Dark Eyes, though, is a little more subtle than a new hairdo or an old war don’t – it’s a question of form. Whereas UNIT: Dominion was consciously cinematic, but still retained the spirit of a traditional Doctor Who adventure, Dark Eyes is another “concept album” from Briggs, closer in structure and tone to one of his grim Dalek Empire epics than anything that Big Finish have previously put out under a Doctor Who banner. It is defined by incident, but carried by character. It is about hope, but abounding with despair. It’s a story that hones in on just two – perhaps three, if you’re prepared to stretch a point – people, and uses the explosions erupting all around them to dissect their souls.

Of its four episodes, “The Great War” is the one most redolent of traditional Doctor Who, as it has to throw our wounded hero into a situation in which he can meet his new companion, whose life he’s evidently vowed to save. Even this is presented in a highly-stylised manner, though, as the narrative flits between the Doctor’s suicidal collision course with the end of time, which Straxus interrupts by dangling the carrot of hope and purpose, and the Doctor’s exploits in Great War France. From there, the adventure adopts the relatively rare (for Who) form of a hunt across space and time, as the Doctor and his new charge Molly are pursued by the Dalek Time Controller and his sinister agents. It’s like an inspiring inversion of The Chase, where the terror is all-pervading and real, and the only humour of the sort you’d generally find in the vicinity of gallows.

Of its four episodes, “The Great War” is the one most redolent of traditional Doctor Who, as it has to throw our wounded hero into a situation in which he can meet his new companion, whose life he’s evidently vowed to save. Even this is presented in a highly-stylised manner, though, as the narrative flits between the Doctor’s suicidal collision course with the end of time, which Straxus interrupts by dangling the carrot of hope and purpose, and the Doctor’s exploits in Great War France. From there, the adventure adopts the relatively rare (for Who) form of a hunt across space and time, as the Doctor and his new charge Molly are pursued by the Dalek Time Controller and his sinister agents. It’s like an inspiring inversion of The Chase, where the terror is all-pervading and real, and the only humour of the sort you’d generally find in the vicinity of gallows.  Dark Eyes’ narrative is carried as much by the new companion as it is the grieving, straw-clutching Doctor – she is, in fact, the eponymous ‘Dark Eyes’. Molly’s forceful Irish brogue that serves as an aural contrast to the eighth Doctor’s velvet RP speaks to the differences in the character’s attitudes on this adventure, which often casts the companion in the steadying role, as opposed to vice-versa, at times showing up the Doctor’s emotional intemperance – something that Paul McGann and Primeval star Ruth Bradley each play to beautifully. It’s a fresh and exhilarating dynamic, which is all the more remarkable as this is becoming increasingly hard to achieve the more travelling companions that the itinerant Gallifreyan accrues. One of the most moving moments in the story – and one of the key moments, I think, from the Doctor’s standpoint – sees Molly calmly mention some of the hardships and losses that she’s had to suffer through in her lifetime, the total sum of which hasn’t driven her to the level of indulgent despair that the Doctor is currently wallowing in. She’s the hope that the Doctor is so desperately seeking – it’s right there, embodied in her brave, truculent spirit. The Doctor might think that he’s been sent to save Molly O’Sullivan, but Dark Eyes is more the story of how she saves him.

Dark Eyes’ narrative is carried as much by the new companion as it is the grieving, straw-clutching Doctor – she is, in fact, the eponymous ‘Dark Eyes’. Molly’s forceful Irish brogue that serves as an aural contrast to the eighth Doctor’s velvet RP speaks to the differences in the character’s attitudes on this adventure, which often casts the companion in the steadying role, as opposed to vice-versa, at times showing up the Doctor’s emotional intemperance – something that Paul McGann and Primeval star Ruth Bradley each play to beautifully. It’s a fresh and exhilarating dynamic, which is all the more remarkable as this is becoming increasingly hard to achieve the more travelling companions that the itinerant Gallifreyan accrues. One of the most moving moments in the story – and one of the key moments, I think, from the Doctor’s standpoint – sees Molly calmly mention some of the hardships and losses that she’s had to suffer through in her lifetime, the total sum of which hasn’t driven her to the level of indulgent despair that the Doctor is currently wallowing in. She’s the hope that the Doctor is so desperately seeking – it’s right there, embodied in her brave, truculent spirit. The Doctor might think that he’s been sent to save Molly O’Sullivan, but Dark Eyes is more the story of how she saves him.Briggs’ treatment of the Daleks is similarly pioneering at times – another feat that’s noteworthy given the great strides made by both Big Finish and BBC Wales in recent years. The third instalment explores the interesting notion of post-Time War (and thus, presumably, considerably post-Asylum of the Daleks) redemption for the Dalek race, and what form this might take. The writer toys cruelly with the Doctor’s passions and prejudices here, entwining them with his search for hope and the credulity that goes along with it. The idea of “a life outside the shell”, and retro-engineered Kaled children laughing at play, are such far-fetched conceits that in any other story the listener would dismiss them out of hand as the products of evil Dalek manoeuvrings, but here the Doctor is grudgingly accepting of them, imbuing the whole episode with a thrilling sense of plausibility that even Helen Raynor’s Evolution of the Daleks television two-parter never seriously engendered.

Whilst Briggs was keen to make what he calls “The Molly Era” of the eighth Doctor’s life as intense as possible for the pair, resulting in four scripts that stick with them almost exclusively, the sole competing thread revolves around Straxus and his peculiar role in both defending against and advancing the Dalek Time Controller’s master plan. Presumably as the incomparable Nickolas Grace was unavailable to reprise the role, Protect and Survive’s Peter Reagan was cast to step into the next incarnation of the Time Lord’s shoes, moving the part away from the sort of bureaucratic mystification that had defined the character in stories past and into more exhorting territory. Reagan’s voice has an imperious, authoritarian tone that fits the character’s circuitous journey in Dark Eyes perfectly, leading us to an unforeseen and prescient development that, listening to the production again recently for the purpose of this article, put me very much in mind of The Name of the Doctor’s climactic reveal, albeit in a clear-cut black and white as opposed to a dark and muddy greyscale.

Indeed, Dark Eyes has far more in common with the Doctor Who of television today than it does either the classic series or even McGann’s American one-off. Its intelligence, tone and careful character development all reflect the high standards to which fans have become accustomed, on occasion even satisfying desires that the television series can’t hope to, thanks to both the vast visual scope of the audio medium and its narrower target audience. Briggs may have conceived Dark Eyes as his second “concept album”, but in its development it’s surpassed even that. It’s a digest of despair and a hatful of hope, charged with all the energy of an older and edgier eighth Doctor and his feisty Irish charge. These four expansive episodes have all the weight and consequence of several seasons’ worth of stories, precision-engineered into one fast-flying box set. That’s not bad going for forty quid.

Dark Eyes is currently available to download from BigFinish Productions for just £35.00, though due to its popularity the company often reduce the price as part of a short-lived promotion, most recently as one of Paul McGann’s personal picks. Keep an eye out for future promotions if you’re hard-up. The CD box set version (which also comes with a free download) is currently just five pounds more than the download-only version.

Read retro Doctor Who reviews @

Published on October 01, 2013 06:24

September 26, 2013

Book Review | Marabou Stork Nightmares by Irvine Welsh

I’m a pretty typical human being when it comes to attitudes towards other species. If it has a couple of arms and a pair of legs, I’ll invite it into my home, feed it, and probably clean up its excrement. Indeed, one such furry mammal has been knocking about the Wolverson homestead for the better part of a decade now. If it has a beak and wings, however, I’m much more cautious. Depart even further from the human form, and all bets are off. Only yesterday I perpetrated a massacre of dragonfly in my garage gym (though only, I should add, after turning off the light and opening up the door for a few minutes, giving them at least the chance of street-lamp salvation). And so the esteemed Mr Welsh chose well when he selected a Marabou Stork to embody the rottenness and evil festering in his second novel’s storyteller’s soul. The African vulture-like scavenger, often nicknamed the ‘Undertaker Bird’ due to its funereal countenance, has little about its appearance or conduct that make it either attractive or sympathetic to most readers. It looks and acts in such a way that is so far removed from what we might vainly endorse that it’s easily dismissed as irredeemably abhorrent – just like about three-quarters of the characters in Marabou Stork Nightmares, which, for all its transcendental trappings, ultimately boils down to an ad absurdumexamination of prejudice in at least two of its most ‘popular’ contemporary forms.

I’m a pretty typical human being when it comes to attitudes towards other species. If it has a couple of arms and a pair of legs, I’ll invite it into my home, feed it, and probably clean up its excrement. Indeed, one such furry mammal has been knocking about the Wolverson homestead for the better part of a decade now. If it has a beak and wings, however, I’m much more cautious. Depart even further from the human form, and all bets are off. Only yesterday I perpetrated a massacre of dragonfly in my garage gym (though only, I should add, after turning off the light and opening up the door for a few minutes, giving them at least the chance of street-lamp salvation). And so the esteemed Mr Welsh chose well when he selected a Marabou Stork to embody the rottenness and evil festering in his second novel’s storyteller’s soul. The African vulture-like scavenger, often nicknamed the ‘Undertaker Bird’ due to its funereal countenance, has little about its appearance or conduct that make it either attractive or sympathetic to most readers. It looks and acts in such a way that is so far removed from what we might vainly endorse that it’s easily dismissed as irredeemably abhorrent – just like about three-quarters of the characters in Marabou Stork Nightmares, which, for all its transcendental trappings, ultimately boils down to an ad absurdumexamination of prejudice in at least two of its most ‘popular’ contemporary forms.Still, those who asked, “What the fuck’s a Marabou Stork?” when they saw this title were missing the point rather. Whilst the Stork is, in most respects, the slow-beating black heart of the novel, its façade within the fiction is arbitrary; more to do with the protagonist’s keen interest in ornithology, time spent living in South Africa and - above all else - physical attributes than it is a dispassionate impression of evil. The real question here is, surely, “What’s the fuck’s a Marabou Stork nightmare?”, and it’s a question not so easily answered by Wikipedia. Allow me to explain.

“The Stork’s the personification of all this badness. If I kill the Stork I’ll kill the badness in me. Then I’ll be ready to come out of here, to wake up, to take my place in society and all that shite.”

From the novel’s earliest passages, it’s apparent that the eponymous nightmares aren’t just dreams of the type that would make your pillow ache, but snapshots of another level of existence; a purgatory of sorts, where Roy Strang, erstwhile Hibs Cashie and constant centre of sexual abuse, is driven to exterminate one particular Marabou Stork that, for some reason, he views as the distillation of all evil. Meanwhile, his body lies comatose in an Edinburgh hospital, where it plays host to all manner of eccentric visitors, each of which threaten to distract the once-top boy from his all-consuming Stork hunt, stirring memories of his unsavoury past and bringing the reality that he’s so desperate to flee ever closer. It’s Life on Mars - only earlier, backwards and Scottish. Let me take you DEEPER…

From the novel’s earliest passages, it’s apparent that the eponymous nightmares aren’t just dreams of the type that would make your pillow ache, but snapshots of another level of existence; a purgatory of sorts, where Roy Strang, erstwhile Hibs Cashie and constant centre of sexual abuse, is driven to exterminate one particular Marabou Stork that, for some reason, he views as the distillation of all evil. Meanwhile, his body lies comatose in an Edinburgh hospital, where it plays host to all manner of eccentric visitors, each of which threaten to distract the once-top boy from his all-consuming Stork hunt, stirring memories of his unsavoury past and bringing the reality that he’s so desperate to flee ever closer. It’s Life on Mars - only earlier, backwards and Scottish. Let me take you DEEPER…DEEPER

DEEPER - - - - - - - - - - - - The novel regularly segues between Roy’s hunt for the Stork in Africa and the story of his real life, with his near-vegetative impressions of his hospital room serving as a bridge between the two. Some cuts are measured; reflective, even. Others are abrupt as Welsh sucks the reader down into the Marabou Stork nightmare without warning, or blasts them up and out Africa and into Fat Hell (Fathell, Midlothian, population 8,619) where stylish men with decent IQs are getting “into the violence just for itself.”

“The largest of the Marabous came forward. - Looks like it’s sort ay panned oot tae oor advantage, eh boys, the creature observed.

It tore a large piece from a bloodied flamingo carcass with a ripping sound, and swallowed it whole.”

Throughout, though, the two parallel tales are constantly mirroring each other, almost serving as allegories of one another, until they eventually become inseparable. The leptoptilos crumeniferus hunt reads like a Victorian explorer pastiche, albeit one unfettered by the morality and decency championed by the heroes of those tales. Roy’s youth in Scotland, adolescence in Apartheid Johannesburg, and early adulthood as a Hibs hooligan are presented in the author’s trademark phonetic style, creating a powerful contrast with the more prosaic coma world that only serves to emphasise the cross-pollination of themes.

Naturally, I gravitated towards what I’d call the ‘main narrative’ – the story of Roy’s life. Whilst the stream-of-consciousness elements do their job well, I’d always be itching to ditch the literal chase and cut back to the figurative one. It’s clear from early on that Roy isn’t a patch on any of the central Trainspotting characters, but in a sense that’s what makes him so interesting. He isn’t so much a fascinating character as he is a dull one that interesting things happen to. And when I say ‘interesting’, obviously I mean ‘horrendous’. Born into a family as low on the social ladder as they are high up in their tenement, Roy is offered a brief beacon of hope in his youth, when his family emigrate to South Africa, where the colour of their skin passports them to the opposite side of the class divide. It doesn’t take long, though, for Roy’s resident uncle to start molesting him, or for Roy’s lunatic father to run into trouble with the law, resulting in a swift return home to the schemes of Scotland, where Roy drifts into a life of computer-programming during the week and swedgin’ at the weekends. But, inevitably, the scheduled swedges soon lead to something far more sinister.

Naturally, I gravitated towards what I’d call the ‘main narrative’ – the story of Roy’s life. Whilst the stream-of-consciousness elements do their job well, I’d always be itching to ditch the literal chase and cut back to the figurative one. It’s clear from early on that Roy isn’t a patch on any of the central Trainspotting characters, but in a sense that’s what makes him so interesting. He isn’t so much a fascinating character as he is a dull one that interesting things happen to. And when I say ‘interesting’, obviously I mean ‘horrendous’. Born into a family as low on the social ladder as they are high up in their tenement, Roy is offered a brief beacon of hope in his youth, when his family emigrate to South Africa, where the colour of their skin passports them to the opposite side of the class divide. It doesn’t take long, though, for Roy’s resident uncle to start molesting him, or for Roy’s lunatic father to run into trouble with the law, resulting in a swift return home to the schemes of Scotland, where Roy drifts into a life of computer-programming during the week and swedgin’ at the weekends. But, inevitably, the scheduled swedges soon lead to something far more sinister.“I realised what we had done, what we had taken. Her beauty was little to do with her looks, the physical attractiveness of her. It was to do with the way she moved, the way she carried herself. It was her confidence, her pride, her vivacity, her lack of fear, her attitude. It was something even more fundamental and less superficial than those things. It was her self, or her sense of it.”

As the Marabou Stork nightmares unfold, it becomes clear that the Stork is representative of more than just “badness”; it’s representative of something specific, a most particular evil. The book’s most harrowing chapter tells of a stunning flamingo that runs afoul of a muster of Storks, who strip her of everything that she has but her life. They imprison her, rape her, demean her. And when she tries to pursue justice, she finds herself put on public exhibition; a defendant in all but name. Subjected to Freudian models of justice (“Female sexuality is deemed by nature to be masochistic, hence rape cannot logistically take place since it directly encounters the argument that all women want it anyway…”); accusations of not saying “no the proper way”; and even allegations of being a “rape fantasist”, Miss X is systematically destroyed, all the while her face registering “disbelief, fear, and self-hate” at her own impotence. It’s not much of a spoiler by this point to say that our boy Roy was amongst this muster of Storks, his guilt and shame fuelling not only his fugue, but the quest that his comatose mind has devised for itself – destruction of evil, destruction of self. “Self-deliverance with a plastic bag”.

“It came tae ays with clarity; these are the cunts we should be hurtin, no the boys wi knock fuck oot ay at the fitba… …we screw over each other’s hooses when there’s fuck all in them, we terrorise oor ain people. These cunts though: these cunts wi dinnae even fuckin see. Even when they’re aw around us.”

As ever, though, with Welsh, there’s a sting in the tale. I thought that I had Marabou Stork Nightmares all worked out from the ‘Miss X’ incident onwards, but the wily Scot employs Easton-Ellis-esque trickery to completely throw off the idiot savant reader. Roy’s candid narration gradually engenders sympathy for the devil, and in a late twist Welsh uses this perverse compassion to powerfully drive home the patterns of nature – predators preying, scavengers scavenging, the abused abusing, the powerless seizing power – and circumstance that underpin both his plot and, I suspect, his point. Marabou Stork Nightmares would have been brilliant without the misdirection. With it, it carries all the hallmarks of genius.

As ever, though, with Welsh, there’s a sting in the tale. I thought that I had Marabou Stork Nightmares all worked out from the ‘Miss X’ incident onwards, but the wily Scot employs Easton-Ellis-esque trickery to completely throw off the idiot savant reader. Roy’s candid narration gradually engenders sympathy for the devil, and in a late twist Welsh uses this perverse compassion to powerfully drive home the patterns of nature – predators preying, scavengers scavenging, the abused abusing, the powerless seizing power – and circumstance that underpin both his plot and, I suspect, his point. Marabou Stork Nightmares would have been brilliant without the misdirection. With it, it carries all the hallmarks of genius.A note of caution for e-bookers: Marabou Stork Nightmares uses a lot of creative typography, most of which hasn’t been typeset in the iTunes e-book, but cut and pasted in as low-resolution images. Not only does this look terrible (due to excessive pixilation), but the text is unreadable if being read on a mobile device as it can’t be enlarged. Worse still, this particular digital edition is riddled with typographical errors not present in the paperback edition, and hasn’t even been properly typeset (there is a superfluous double space between every line break, as per the above right iPhone screengrab). Unless you’re in love with trees or passionate about the preservation of shelf space, either get the paperback (which is currently cheapest online at Play, where it’s being sold for £5.37 with free delivery) or save a few pennies more and get the Kindle edition from Amazon for £5.22. I’ve only tested the free sample of the Kindle edition, but it doesn’t seem to be plagued by the same typesetting problems as the iTunes version, and the text-based images are fewer and farther between.

Published on September 26, 2013 07:00

September 24, 2013

The One-Listen Lowdown | AM by the Arctic Monkeys

A number of things have always drawn me to the Arctic Monkeys. First and foremost, they hail from just a few miles away from the village where I grew up, and their music seems to capture the quintessence of the area as it appears to those of our generation. For me, this lends their songs a raw sense of reality that’s heightened by their already-idiosyncratic and alluring sound, which remains unique irrespective of which genre they’re currently dabbling in. Perhaps most importantly of all though, they’re one of the best storytelling bands around today - their songs aren’t just music and lyrics, but short stories and evocative allegories fuelled by love, lust and drunken melodrama, and often capped with a torturous twist. With the Arctic Monkeys, you don’t so much buy an album as an aural anthology - and this fifth one is no different. “Takes a sip of your soul, and it sounds like...”

AMmarks a significant moment in the band’s history as they’ve now reached those self-assured heights where they’re confident enough to forget about an encapsulating album title and just sign off on a record eponymously, or more accurately, in a Velvet Underground-inspired move, simply initial it. But with its deliberate “after midnight” mood and a cover that alludes to amplitude modulation, there’s far more to AM than meets the eye. Yes, it may be their untitled white album; their Blur, but it’s also something of a Zooropa.

“Do I Wanna Know?” is the band’s most effective album-opener since “Brianstorm”. Slow, heavy and driven by drums and spilt drinks on settees, the track builds a sense of mammoth expectation that the well-known 2012 single that follows it quickly delivers upon. Fusing the geek chic of Thunderbirds and Lone Ranger references with the Monkeys’ trademark skewed and insightful perspective, “R U Mine?” begs a question that the rest of the album looks to answer.

“Do I Wanna Know?” is the band’s most effective album-opener since “Brianstorm”. Slow, heavy and driven by drums and spilt drinks on settees, the track builds a sense of mammoth expectation that the well-known 2012 single that follows it quickly delivers upon. Fusing the geek chic of Thunderbirds and Lone Ranger references with the Monkeys’ trademark skewed and insightful perspective, “R U Mine?” begs a question that the rest of the album looks to answer.“From the bottom of your heart, the relegation zone,” croons Alex Turner at the start of AM’s third track, “One for the Road” - an experimental offering that pays homage to ’80s rock opera, littered with as many cutaway choruses as it is intriguing football metaphors. “Arabella” then sees the group turn back to more familiar territory with a tongue-twisting lovesong that has a pleasing penchant for cosmic similes.

The most outstanding track on the first side of the LP though is “I Want It All”, which sees the Sheffield songsters turned Californian bikers dial back a further decade to tap into the riffy, falsetto-filled world of the ’70s. Redolent of T-Rex, yet still inimitably the Arctic Monkeys, “I Want It All” has an intoxicating, radio-friendly feel that mark it out as a sure-fire future single. “No 1 Party Anthem”, conversely, actively eschews the inferences inevitably drawn from its title. It’s more of a dirge for the hesitant man stood alone in the corner devising “drunken monologues” than it is an anthem for those looking good on the dancefloor. Idle and insidious, and with a hook that feels like it should be slurred rather than sang, this song is AM at its most edgy; lyrically delightful in its luxurious languor.

The most outstanding track on the first side of the LP though is “I Want It All”, which sees the Sheffield songsters turned Californian bikers dial back a further decade to tap into the riffy, falsetto-filled world of the ’70s. Redolent of T-Rex, yet still inimitably the Arctic Monkeys, “I Want It All” has an intoxicating, radio-friendly feel that mark it out as a sure-fire future single. “No 1 Party Anthem”, conversely, actively eschews the inferences inevitably drawn from its title. It’s more of a dirge for the hesitant man stood alone in the corner devising “drunken monologues” than it is an anthem for those looking good on the dancefloor. Idle and insidious, and with a hook that feels like it should be slurred rather than sang, this song is AM at its most edgy; lyrically delightful in its luxurious languor.After the pace-bomb, AM doesn’t even try to recover its verve immediately, the band electing to follow up their moody musings with a gentle and mellifluous interlude in the guise of “Mad Sounds” rather than deliver a wake-up belter. But like the second wind in the early hours, a “Fireside” fuse soon gets the tempo back up with a grandiose rock offering that reeks of the Killers.

Top-ten hit “Why D’You Only Ever Call Me When You’re High?” is vintage Arctic Monkeys, marred only by its brevity and a chorus that, on the first listen, seems to share a similar melody to that of “R U Mine?” There’s no marring “Snap Out of It”, however, which sounds very much like I’d imagine an Arctic Monkeys / Kaiser Chiefs supergroup would. What it lacks in lyrical weight it makes up for tenfold in catchiness - it’s the clear first-listen standout.

Top-ten hit “Why D’You Only Ever Call Me When You’re High?” is vintage Arctic Monkeys, marred only by its brevity and a chorus that, on the first listen, seems to share a similar melody to that of “R U Mine?” There’s no marring “Snap Out of It”, however, which sounds very much like I’d imagine an Arctic Monkeys / Kaiser Chiefs supergroup would. What it lacks in lyrical weight it makes up for tenfold in catchiness - it’s the clear first-listen standout.With the Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme on board, the salacious disco number “Knee Socks” is almost as instant a winner, but not quite. However, with its inventive “coughdrop-coloured tongue” and scruff-of-socks “sweet spots”, AM’s penultimate track is likely to grow into a firm favourite as I delve deeper.

The album concludes with a gentle, beautiful grind of track that’s abounding with as many ’leccy meters and Ford Cortinas as it is declarations of desire. “I Wanna Be Yours” might be the sort of trite title that involuntarily bleeds into the background, but the John Cooper Clarke-inspired mantra proves to be the vacuum cleaner to the listener’s dust.

The fifth of five genre-busting records linked by an unyielding South Yorkshire brogue and sharp-as-Sheffield writing, AM feels like the long-since-held ace up the Arctic Monkeys’ sleeves. It can’t match Favourite Worst Nightmare for fury or the haunting Humbug for power and weight, but it borrows a little of something from each album to date, adding a time-travelling, hip-hop vibe into the mix that hauls the listener over forty-odd years’ sounds in a little under forty minutes. The no-frills ‘sunglasses and soundwaves’ statement of a cover tells you everything that you need to know about this one. Suck it and see - you might just like it. AM is available to download from Amazon for £6.99. The CD version is currently cheapest online at Play, where it’s currently on sale for £8.75, but at Amazon , you can get the CD bundled with an ‘Amazon AutoRip’ 256kbps MP3 download for just 24p more - only a pound more than you’d pay to iTunes for the download alone.

Published on September 24, 2013 07:01

September 22, 2013

DVD Review | Doctor Who: The Green Death (Special Edition)

Published on September 22, 2013 07:25

September 15, 2013

DVD Review | Doctor Who: The Ice Warriors

Coming Soon to

The History of the Doctor:

The Green Death (Special Edition) and the Scream of the Shalka DVDs

Coming Soon to

The History of the Doctor:

The Green Death (Special Edition) and the Scream of the Shalka DVDs

Published on September 15, 2013 07:37

September 12, 2013

iTunes Film Review | Star Trek Into Darkness directed by J J Abrams

Since going ‘all in’ with Apple TV, my wife and I have bought the majority of our Saturday night movies through iTunes. iTunes’ new releases are generally slightly cheaper than their Blu-ray counterparts (anything from a pound to five or six quid, sometimes); you don’t have to leave your sofa to get them; and they’re available to stream from the moment that you purchase them (you can download a copy to your iTunes library to keep later). And for the sort of compromised-upon comedies that we generally opt for, the quality is never an issue. In fact, we don’t even bother with full 1080p downloads – a 1280 x 720 frame with an average bitrate of 4000kbps or so is more than adequate to sharply render a moping Leslie Mann or a cuckolding Rose Byrne. Should we ever extend our screen beyond 40” (which is unlikely, given the dimensions of the alcove in which our TV hangs), we’ve always got the option of downloading the film again in full 1080p. It’s sat there forever, in ‘Purchased’, until such time as shame forces us to hide it, as well it might with Identity Thief. Even then, a hidden purchase can be unhidden again at any time simply by logging into our iTunes account.

Since going ‘all in’ with Apple TV, my wife and I have bought the majority of our Saturday night movies through iTunes. iTunes’ new releases are generally slightly cheaper than their Blu-ray counterparts (anything from a pound to five or six quid, sometimes); you don’t have to leave your sofa to get them; and they’re available to stream from the moment that you purchase them (you can download a copy to your iTunes library to keep later). And for the sort of compromised-upon comedies that we generally opt for, the quality is never an issue. In fact, we don’t even bother with full 1080p downloads – a 1280 x 720 frame with an average bitrate of 4000kbps or so is more than adequate to sharply render a moping Leslie Mann or a cuckolding Rose Byrne. Should we ever extend our screen beyond 40” (which is unlikely, given the dimensions of the alcove in which our TV hangs), we’ve always got the option of downloading the film again in full 1080p. It’s sat there forever, in ‘Purchased’, until such time as shame forces us to hide it, as well it might with Identity Thief. Even then, a hidden purchase can be unhidden again at any time simply by logging into our iTunes account.But until now, I’ve generally deferred to Blu-ray for movies that I felt might benefit from the extraordinary bitrates that Blu-rays offer – sprawling epics like The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, where someone has agonised over every single one of those million plus pixels that constitute each frame. This time, though, I thought that I’d really test iTunes’ mettle with something more challenging than just another bright and breezy romcom: Star Trek Into Darkness, the action-packed J J Abrams blockbuster that has the dubious distinction of being the first Star Trek film that I’ve not seen in a cinema since Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country in 1991, which of course makes my choice of home media for viewing it of even greater importance than usual.

I downloaded the movie and its accompanying ‘iTunes Extras’ in full 1080p, noting with some concern that the files’ average bitrates weren’t much higher than in most of our 720p downloads (the movie’s average is 4737kbps). My initial disenchantment was compounded by my discovery that, for some reason that eludes just about everyone in the Alpha Quadrant, iTunes Extras can’t be accessed readily on recent generations of Apple TV - they only seem to work on your desktop computer or laptop. I’d have been more likely to watch them on my iPad or iPhone than I would my hidden-away, media-serving PC, but the iTunes Extras aren’t accessible on them either. But for an inspired bit of technical jiggery-pokery, the likes of which will surely be beyond the patience, if not the technical skill, of most customers of the iTunes Store, I’d have bought half a lemon here.

I downloaded the movie and its accompanying ‘iTunes Extras’ in full 1080p, noting with some concern that the files’ average bitrates weren’t much higher than in most of our 720p downloads (the movie’s average is 4737kbps). My initial disenchantment was compounded by my discovery that, for some reason that eludes just about everyone in the Alpha Quadrant, iTunes Extras can’t be accessed readily on recent generations of Apple TV - they only seem to work on your desktop computer or laptop. I’d have been more likely to watch them on my iPad or iPhone than I would my hidden-away, media-serving PC, but the iTunes Extras aren’t accessible on them either. But for an inspired bit of technical jiggery-pokery, the likes of which will surely be beyond the patience, if not the technical skill, of most customers of the iTunes Store, I’d have bought half a lemon here.

For those who’ve been enticed by the iTunes Store’s efficient-looking blue button (above) only to find themselves cursing like me, when you download the bonus material to your computer, it is stored by default in a subfolder of your iTunes Media/Movies folder, in this case Star Trek Into Darkness – iTunes Extras. Inside it you’ll find all the bumph used to put a needless DVD menu-like spin on the special features, along with a subfolder labelled ‘videos’, in which the six .m4v files that comprise the bonus material reside. Simply use your software of choice to tag them appropriately (I favour MetaX) and then add the files to your iTunes library. Voila – iTunes Extras not only watchable on your second or third-generation Apple TV, but that can be synced to your Apple devices and enjoyed at your leisure. Anyone would think that you’ve paid for them…In keeping with my meticulous media referencing system, in which only theatrically-released movies can reside in my ‘Films’ library, I elected to set the iTunes Extras’ media type to ‘TV Show’. I would recommend doing this irrespective of your views on what belongs where as it makes the files easier to manage and navigate (within iTunes, television series are treated much like music albums, allowing for multiple tracks – and Apple TV-friendly special features! – within any given season). If you to decide to set the media type to ‘Films’, you’ll be left with half a dozen separate movies suddenly in your library, though I suppose it’s still better than the watch-’em-hunched-over-your-computer option.

For those who’ve been enticed by the iTunes Store’s efficient-looking blue button (above) only to find themselves cursing like me, when you download the bonus material to your computer, it is stored by default in a subfolder of your iTunes Media/Movies folder, in this case Star Trek Into Darkness – iTunes Extras. Inside it you’ll find all the bumph used to put a needless DVD menu-like spin on the special features, along with a subfolder labelled ‘videos’, in which the six .m4v files that comprise the bonus material reside. Simply use your software of choice to tag them appropriately (I favour MetaX) and then add the files to your iTunes library. Voila – iTunes Extras not only watchable on your second or third-generation Apple TV, but that can be synced to your Apple devices and enjoyed at your leisure. Anyone would think that you’ve paid for them…In keeping with my meticulous media referencing system, in which only theatrically-released movies can reside in my ‘Films’ library, I elected to set the iTunes Extras’ media type to ‘TV Show’. I would recommend doing this irrespective of your views on what belongs where as it makes the files easier to manage and navigate (within iTunes, television series are treated much like music albums, allowing for multiple tracks – and Apple TV-friendly special features! – within any given season). If you to decide to set the media type to ‘Films’, you’ll be left with half a dozen separate movies suddenly in your library, though I suppose it’s still better than the watch-’em-hunched-over-your-computer option.

After going through the above rigmarole, it’s a good job that the iTunes Extras offer something that neither the Blu-ray nor DVD releases do – something surprisingly valuable. Together with a smattering of production featurettes available through other media, none of which have any real depth, the iTunes Extras present a near-three-hour “enhanced commentary”. I had no idea what this would be; I was half-expecting an in-vision commentary similar to those that I’ve found on Heroes and Doctor Who Blu-rays in the past, but at 2:42:45 the runtime is significantly longer than the movie. Within the first few minutes of the feature, I realised why.

After going through the above rigmarole, it’s a good job that the iTunes Extras offer something that neither the Blu-ray nor DVD releases do – something surprisingly valuable. Together with a smattering of production featurettes available through other media, none of which have any real depth, the iTunes Extras present a near-three-hour “enhanced commentary”. I had no idea what this would be; I was half-expecting an in-vision commentary similar to those that I’ve found on Heroes and Doctor Who Blu-rays in the past, but at 2:42:45 the runtime is significantly longer than the movie. Within the first few minutes of the feature, I realised why.The enhanced commentary brings the filmmakers into your living room, and by ‘filmmakers’ I don’t just mean the upper echelons of the production crew – I mean everybody with an interesting insight or anecdote to share. The merry-go-round of contributors watch the film with you, talking about how they created the amazing special effects that you’re witnessing on your TV screen; why the script went down a certain road; even why certain roads weren’t travelled. They play certain bits in slow motion and rewind others; sometimes they scribble on the screen like football pundits. If this is what they call ‘enhancement’, then they’ve got a gift for understatement - this is one of the most thorough ‘making of’ features that I’ve ever come across, and that’s no small statement given that I collect classic Doctor Who DVDs.

Star Trek Into Darkness itself looks incredible. Despite its gloomy title, the twelfth Star Trek movie is by far and away the most visually arresting of the saga, combining the colourful flair of the 2009 film with a bold, authentic edge, that the iTunes 1080p download preserves magnificently. I don’t know what compression techniques Apple use to achieve such superb quality at such economic bitrates, but the result is nonetheless stunning. Uniforms scream colour; ships exude the finest of detail. Dark areas of the picture, often prone to pixilation when crudely compressed, generally retain their sharpness, while daylight sequences – which are surprisingly common here for a purported trek into darkness – are, without exception, breathtaking. The Enterprise sinking into the clouds of Earth, or rising from the oceans of Nibiru stand out as particular highlights, as does the more disturbing sequence that sees the Vengeance on an unforgettable collision course with San Francisco, eerily redolent of 9/11. Even the heavy metal, helmeted Klingons benefit from their HD rendering.

The narrative is a wonderfully-weighted thing, dextrously balancing the demands of a mainstream audience hungry for sensational spectacle against the wishes of a decades-old fanbase with quite trenchant views on its Trek. The high-octane pre-title sequence was sufficient to demonstrate the inherent paucity of my pre-purchase chuntering about iTunes’ “misclassification” of the film as ‘Action & Adventure’, and from there the movie only seemed to get faster and hit harder, with barely moments passing between each scintillating set piece. It’s hard to imagine it being received anything less than thunderously in cinemas, and so it’s little surprise that the movie had become the highest-grossing of the whole Star Trek franchise by the time that its run in cinemas ended.

The narrative is a wonderfully-weighted thing, dextrously balancing the demands of a mainstream audience hungry for sensational spectacle against the wishes of a decades-old fanbase with quite trenchant views on its Trek. The high-octane pre-title sequence was sufficient to demonstrate the inherent paucity of my pre-purchase chuntering about iTunes’ “misclassification” of the film as ‘Action & Adventure’, and from there the movie only seemed to get faster and hit harder, with barely moments passing between each scintillating set piece. It’s hard to imagine it being received anything less than thunderously in cinemas, and so it’s little surprise that the movie had become the highest-grossing of the whole Star Trek franchise by the time that its run in cinemas ended.

Yet despite its ubiquitous kerb appeal, the themes that characterise Star Trek Into Darkness are ones that resonate across every incarnation of Gene Roddenberry’s “Wagon Train to the Stars”, from the rousing allegories embedded in the voyages of the original starship Enterprise all the way to the gritty moral dilemmas of war-torn space station Deep Space Nine and the lost and vulnerable USS Voyager. The only difference, really, is that here the moralising is a little closer to home. The kid gloves are gone, along with the theatrics. This time around, the wrath of Khan is as clinical as it is cold, instilling an all-too-familar desire for retribution in the Enterprise captain’s heart.Interestingly, the casting of Sherlock star Benedict Cumberbatch as Khan Noonien Singh caused uproar amongst Trekkies and media pundits alike, who accused the moviemakers of “whitewashing” the production. Whilst it’s possible to see where they were coming from, given the themes of the film I think that the producers’ refusal to perpetuate racial stereotyping should be applauded - another exotic-looking Khan in the Ricardo Montalbán mould would have sent out the wrong message. Moreover, he wouldn’t have been such an effective and frightening reflection of Kirk and Spock, thus undermining the central conceit of the story.

Yet despite its ubiquitous kerb appeal, the themes that characterise Star Trek Into Darkness are ones that resonate across every incarnation of Gene Roddenberry’s “Wagon Train to the Stars”, from the rousing allegories embedded in the voyages of the original starship Enterprise all the way to the gritty moral dilemmas of war-torn space station Deep Space Nine and the lost and vulnerable USS Voyager. The only difference, really, is that here the moralising is a little closer to home. The kid gloves are gone, along with the theatrics. This time around, the wrath of Khan is as clinical as it is cold, instilling an all-too-familar desire for retribution in the Enterprise captain’s heart.Interestingly, the casting of Sherlock star Benedict Cumberbatch as Khan Noonien Singh caused uproar amongst Trekkies and media pundits alike, who accused the moviemakers of “whitewashing” the production. Whilst it’s possible to see where they were coming from, given the themes of the film I think that the producers’ refusal to perpetuate racial stereotyping should be applauded - another exotic-looking Khan in the Ricardo Montalbán mould would have sent out the wrong message. Moreover, he wouldn’t have been such an effective and frightening reflection of Kirk and Spock, thus undermining the central conceit of the story.

When it comes down to it though, Cumberbatch didn’t get the job because of the colour of his skin – he got it because he was the right actor for the part. I love him as the 21st century Holmes, but here he’s got even more gravitas. His sonorous tones should come from a man twice his age, and the steel in his green-eyed gaze is plausibly that of a genetically-engineered superman. He’s the best Trek villain ever to grace the silver screen, and I sincerely hope that we haven’t seen the last of him.

When it comes down to it though, Cumberbatch didn’t get the job because of the colour of his skin – he got it because he was the right actor for the part. I love him as the 21st century Holmes, but here he’s got even more gravitas. His sonorous tones should come from a man twice his age, and the steel in his green-eyed gaze is plausibly that of a genetically-engineered superman. He’s the best Trek villain ever to grace the silver screen, and I sincerely hope that we haven’t seen the last of him. Of course, Khan isn’t the one trekking into darkness; he’s already there. What’s most disturbing about this film is the darkness that it shrouds our heroes in, at times perhaps too completely. Star Trek Into Darkness was responsible for more than one popcorn spillage in our house, all of which were borne of anger or sheer incredulity. The parallels briefly drawn between James T Kirk and George W Bush pissed me off as much as they did Spock (“There’s a sole, yet-to-be-tried terrorist hiding on Qo’noS. Never mind the Klingons, let’s bomb the shit out of Qo’noS!”), but ultimately my indignation drew me deeper into Chris Pine’s impassioned portrayal, thus increasing the eventual payoff when the cracks of light started to shine through Kirk again. This example effectively sums up my views on the whole film in microcosm, as it hooked me with fury and then dragged me through just about every emotional state imaginable, eventually leaving me uplifted – but knackered.

Of course, Khan isn’t the one trekking into darkness; he’s already there. What’s most disturbing about this film is the darkness that it shrouds our heroes in, at times perhaps too completely. Star Trek Into Darkness was responsible for more than one popcorn spillage in our house, all of which were borne of anger or sheer incredulity. The parallels briefly drawn between James T Kirk and George W Bush pissed me off as much as they did Spock (“There’s a sole, yet-to-be-tried terrorist hiding on Qo’noS. Never mind the Klingons, let’s bomb the shit out of Qo’noS!”), but ultimately my indignation drew me deeper into Chris Pine’s impassioned portrayal, thus increasing the eventual payoff when the cracks of light started to shine through Kirk again. This example effectively sums up my views on the whole film in microcosm, as it hooked me with fury and then dragged me through just about every emotional state imaginable, eventually leaving me uplifted – but knackered.And the titular darkness isn’t all Khan’s, Kirk’s, or even Spock’s - there are countless moments in the film that are desperately uncomfortable in of themselves. Noel Clarke’s haunting turn allows Abrams to vest a single glass of water with a greater sense of dread than Star Trek: Nemesis director Stuart Baird could the colossal Romulan Scimitar, so imagine what he’s able to do with a terrorist with superpowers and a stealthy, experimental Federation warship. Outer-space duels of The Wrath of Khan kind couldn’t hope to cut as deeply these days as Khan’s one-man war of terror against the Federation does here. It’s right on the zeitgeist.

Fortunately Roberto Orci, Alex Kurtzman and Damon Lindelof were sagacious enough to saturate their polemical plot with relentless fan service, which ranges from reintroducing classic character Dr Carol Marcus in a younger, sexier guise (Alive Eve) – and, obviously, stripping her down to her bra and panties in the process (as above) – to making about a million jokes about the steely Sulu’s yearn for captaincy; having Uhura and Spock air their dirty laundry in public; allowing Scotty take a moral, but still somehow comic, stand; and having the dénouement turn on a tribble. Most remarkably of all though, the script cleverly mirrors the events of the second Star Trek motion picture, albeit with a disturbing inversion, adding a further level of tension for not only those familiar with the 1982 masterpiece, but – thanks to a welcome, expositional Leonard Nimoy cameo – everybody else watching too. You’ve got to admire the writers’ gall: create your own, unbound Star Trek universe to engender an ‘anything can happen’ vibe, then turn to the inescapability of fate to prove it.

Fortunately Roberto Orci, Alex Kurtzman and Damon Lindelof were sagacious enough to saturate their polemical plot with relentless fan service, which ranges from reintroducing classic character Dr Carol Marcus in a younger, sexier guise (Alive Eve) – and, obviously, stripping her down to her bra and panties in the process (as above) – to making about a million jokes about the steely Sulu’s yearn for captaincy; having Uhura and Spock air their dirty laundry in public; allowing Scotty take a moral, but still somehow comic, stand; and having the dénouement turn on a tribble. Most remarkably of all though, the script cleverly mirrors the events of the second Star Trek motion picture, albeit with a disturbing inversion, adding a further level of tension for not only those familiar with the 1982 masterpiece, but – thanks to a welcome, expositional Leonard Nimoy cameo – everybody else watching too. You’ve got to admire the writers’ gall: create your own, unbound Star Trek universe to engender an ‘anything can happen’ vibe, then turn to the inescapability of fate to prove it.This brings me to the most arresting thing about Star Trek Into Darkness; the same thing that made its 2009 forerunner so outstanding: the relationship between its two central heroes, Zachary Quinto’s Spock and Chris Pine’s Kirk. Insofar as the first film told of the beginning of this legendary friendship, which the characters’ youth injected with a much hotter edge, this second film tells of the cementing of it. In the deafening echo of lives and deaths that they’ve never experienced, Star Trek Into Darkness brings the two nascent legends full circle in the most moving of ways. If their Star Trek II homage scene doesn’t stir up a manly tear, nowt will.

In all, I paid a pound and a penny less for my digital copy of Star Trek Into Darkness than I would have done for the Blu-ray edition. There is no question that the Blu-ray would have offered me superior sound and picture quality, and I daresay that were I to compare the two on my own equipment objectively, there’d be some discernible difference - but it doesn’t automatically follow that the difference would be worthwhile. Indeed, I’m so impressed with the quality of the iTunes 108op movie that the point is effectively moot, and with it I’ve also got the welcome option of downloading 480p or 720p versions to my iPhone and iPad for enjoyment on the move at any time, which I’ll certainly do at some point in the near future. I’m not sure what the quality and limitations of the free digital copies that come with the Blu-ray and Blu-ray 3D releases are like, but I’ve yet to come across a free digital copy worth the paper that it’s printed on.

In all, I paid a pound and a penny less for my digital copy of Star Trek Into Darkness than I would have done for the Blu-ray edition. There is no question that the Blu-ray would have offered me superior sound and picture quality, and I daresay that were I to compare the two on my own equipment objectively, there’d be some discernible difference - but it doesn’t automatically follow that the difference would be worthwhile. Indeed, I’m so impressed with the quality of the iTunes 108op movie that the point is effectively moot, and with it I’ve also got the welcome option of downloading 480p or 720p versions to my iPhone and iPad for enjoyment on the move at any time, which I’ll certainly do at some point in the near future. I’m not sure what the quality and limitations of the free digital copies that come with the Blu-ray and Blu-ray 3D releases are like, but I’ve yet to come across a free digital copy worth the paper that it’s printed on.

As regards the iTunes Extras debacle, I’m block-capitals furious that the special features didn’t work as I’d wanted them to ‘out of the box’, as it were, but I’m also mindful that even if they had done, I’d have eventually retagged them all anyway, as I do with all my iTunes purchases (the metadata of which generally leaves much to be desired, as proven by Star Trek Into Darkness, which doesn’t have its director tagged and has half its short description missing). If, like me, you’re a control freak and moderately-techy geek with an unhealthy interest in absorbing hours of exhaustive bonus material, then I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend purchasing this movie through iTunes. Otherwise, for ease alone I’d urge you to stump up the extra 101p for the Blu-ray – you’ll save yourself a hell of a headache.The digital edition of Star Trek Into Darkness is available from iTunes in 1080p HD to buy for £13.99 or to rent for £4.49. Its Blu-ray counterparts, which do not include the iTunes-exclusive enhanced commentary, are currently cheapest at Amazon, where you can buy the 2D edition for £15.00, and ASDA, where you can buy the 3D edition for £18.00.