Dave Barnhart's Blog, page 2

December 27, 2024

Week 4, Day 5: Peace

“Peace I leave with you. My peace I give you. I give to you not as the world gives. Don’t be troubled or afraid.” (John 14:27)

Mystic Nativity, Botticelli, 1500. From Wikimedia Commons

Mystic Nativity, Botticelli, 1500. From Wikimedia CommonsYesterday I talked about how acceptance leads to equanimity, a place where we can experience deep feelings from ourselves and others without overwhelm or minimizing. Acceptance and equanimity are close cousins of peace.

“Peace” is usually thought of as freedom from conflict or trouble, but the Bible often talks about a peace that passes understanding that can be present in the midst of conflict. Jesus says he gives his peace “not as the world gives.” This peace somehow transcends the circumstances of the moment and connects us to something deeper and more eternal. We live with one foot standing in the turbulent present and another foot standing in the peaceable kingdom.

I think of the nativity scenes we create in miniature all over the world in many different styles: a baby in a manger surrounded by loving parents, working-class shepherds, high-falutin’ foreign astrologers, divine beings (angels), and livestock. It’s a snapshot, a diorama, of a peaceable kingdom. We know from the story in Matthew that just out of the dioarama lurks the paranoid King Herod and soldiers who will commit genocide in this tiny Palestinian village. But for the moment: peace.

Martin Luther King, Jr. reminded the American church that “True peace is not merely the absence of tension: it is the presence of justice.” The nativity scenes we create at Christmas do not stick too closely to the gospel in either Matthew or Luke because they reflect an idealized version of the presence of justice, where rich people give away their wealth and workers are welcomed as prophets, where animals and divine beings share space in giving glory to God. Like the peace that Jesus gives, this is not a peace without tension.

Christians tend to talk about a “peace that passes understanding” that we can have in our hearts as a different kind of thing from the socially just peace described by the prophets, but I think that’s where we go wrong. We cannot separate the interior state from the outer, as though Christ’s peace is something I just hold and nurture in my heart for my illusory self. The peace we have within demands expression in action and words. It bubbles up, like a spring of water, and overflows out of us.

I think one of the reasons the socially just peace is so elusive is that too many people try to hold peace inside of themselves, as if it were an individualistic gift. But Jesus does not give peace as the world gives. This is a gift that must be shared.

Prayer: Holy Spirit of Peace, give us a contagious peace that passes understanding. Amen.

December 26, 2024

Week 4, Day 4 (Day After Christmas Day): Acceptance

I have learned how to be content in any circumstance. I know the experience of being in need and of having more than enough; I have learned the secret to being content in any and every circumstance, whether full or hungry or whether having plenty or being poor. I can endure all these things through the power of the one who gives me strength (Philippians 4:11-13).

I’ve already mentioned one of the four immeasurables of Buddhism: lovingkindness. The other three are

universal compassion: feeling the suffering of other beings (and wishing to alleviate it).universal joy: celebrating the happiness and delight of other beings.equanimity: feeling these things equally and not being perturbed. Remaining steady regardless of circumstance and treating other beings equally.Equanimity is not a state of indifference. It’s a state of caring deeply for yourself and others, balanced with an awareness that everything is temporary. Someone who possesses equanimity may feel the depths and heights of emotion, but they are not overwhelmed by it. They’ve broadened their capacity to feel. They can “hold space” for their own emotions and others’. They accept what they feel and do not try to minimize it, inflate it, or push it away.

In the bible passage above, Paul is describing an acceptance that leads to equanimity. He says he can accept whatever comes by adopting the attitude of Christ. As someone who experienced shipwreck, imprisonment, ecstatic visions, and loving community, he was able to take it all in and receive it with gratitude. One verse above is often taken out of context and misread as an individualistic battle cry: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me!” But I think the CEB translation is better here. Paul can accept whatever comes his way with a peace that passes understanding (which I’ll write about tomorrow).

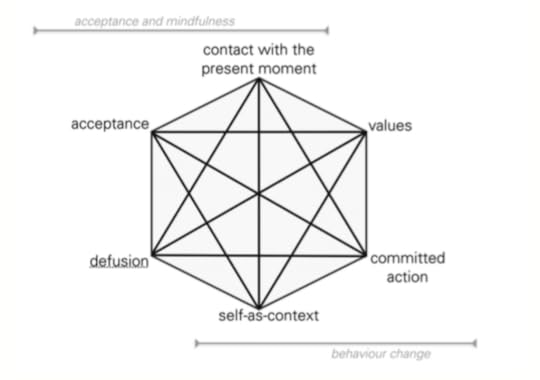

Hexaflex model of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, from Hulbert-Williams et al. (2016).

Hexaflex model of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, from Hulbert-Williams et al. (2016). “Acceptance” doesn’t mean you agree with injustice or are indifferent to pain (which would go against “universal compassion”). Acceptance is simply making a distinction between what we can and cannot control, welcoming feelings and thoughts as responses to our situation without buying into them completely. We have more capacity for acceptance when we are intentionally present to the moment, recognizing that everything—including our own consciousness—is changing.

Christmas contains such highs and lows. Families gather to celebrate, but they can also open old wounds. People talk about the arrival of Christ but also mourn deaths and the absence of loved ones. Communities gather, but many people feel profoundly, existentially alone even when surrounded by people. Even if you have had an emotional or spiritual high during Christmas, the days or weeks after can leave you feeling depleted.

It is a good time to practice acceptance.

I’m including acceptance as a gift and gateway of consciousness because it can help bring us to the present moment, to awareness of all our thoughts and feelings. As we become more aware of our own awareness, we notice our tendency to flee pain and pursue pleasure. We gain a little space to make better self-directed choices instead of just reacting to the crisis or unpleasantness of the moment.

Prayer: Sustainer of All Life, help me accept the things I cannot change, knowing that this equanimity will help me to be more effective in changing what I can. Amen.

December 25, 2024

Week 4, Day 3 (Christmas Day): Lovingkindness

God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him won’t perish but will have eternal life. (John 3:16)

There is a meditation practice that I try to do occasionally called “lovingkindness meditation,” or metta. It involves consciously bringing up a feeling of universal love, and then extending that love to all the beings in the universe.

Usually, you begin in a meditative state, taking slow, deep breaths. You call to mind someone or something who is relatively easy to love: a partner, family member, or even a pet. There is a mantra that goes along with this visualization: “May you be healthy; may you be happy; may you be safe; may you be at peace.”

The idea here is that love is about wishing for others the same things we wish for ourselves. The early church referred to this as agape love, wishing the good for another. It also causes us to reflect that if we have our needs met, we are more likely to be the best version of ourselves.

You next bring to mind someone who you may not love particularly well, but who you can extend this same wish toward, like an acquaintance. Again, you’re invited to consider that if this person has their needs met, if they have the same things you wish for yourself (health, happiness, safety, peace), you are connected in a way that transcends how you feel about them at any given moment.

You continue bringing others to mind, including yourself and, if you are able, your enemies. After all, if your enemies had what you wish for yourself — health, happiness, safety, peace of mind — it is unlikely that you would still be enemies, right? If they had more love, if they had fewer irrational fears, if they were at peace, would they not be different toward you?

Extending lovingkindness to yourself is, for some people, even more difficult than extending it to your enemies. We see our own flaws magnified, as if through a funhouse mirror. Yet if we had the same things we wish for those we love most, would we not be better versions of ourselves? If we had safety, support, physical health, and fewer worries, wouldn’t we be more patient, disciplined, and forgiving?

Loving others as yourself is one of two bedrock commandments in Christianity (Matthew 22:39). In Hinduism and Buddhism, it is one of four “immeasurables” that you strive for. The practice of metta reminds us that this love is not just a sentimental feeling, but an orientation to the whole cosmos. Roberta Bondi summarizes the goal of Christian monasticism this way: to love as God loves — impartially, completely, “like sunshine or rain,” falling on the evil and the good, as Jesus said (Matthew 5:45).

Christmas reveals that God’s very nature is love (1 John 4:8). I believe that as we become more conscious, we begin to notice love at the heart of all things. Like awe and gratitude, lovingkindness is both a gift and a gateway of consciousness. It helps us become more fully ourselves.

Prayer: Love Divine, be born in the world again, at every moment, and in me. Amen.

December 24, 2024

Week 4, Day 2 (Christmas Eve): Gratitude

Brother David Steindl-Rast has been called “The Grandfather of Gratitude.” Two of my favorites quotes of his are below:

“Everything is a gift. The degree to which we are awake to this truth is a measure of our gratefulness, and gratefulness is a measure of our aliveness.”

And

“In daily life we must see that it is not happiness that makes us grateful, but gratefulness that makes us happy.”

I believe gratefulness is another gift and gateway of consciousness, or as Brother David says here, “aliveness.” If you allow yourself to be in awe of your own life, of the color that comes to your eyes or the sound that comes to your ears, it would be difficult to be ungrateful. Steindl-Rast says that gratitude is the beginning of spirituality.

Brother David says gratitude is not just about being thankful for good things that happen to us. We are happy because we are grateful, not grateful because we are happy.

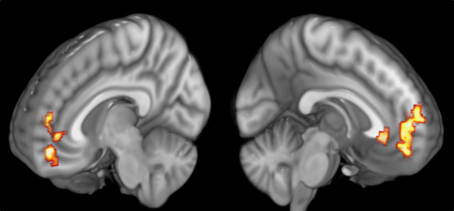

“Neural correlates of gratitude. Medial Prefrontal activity correlating with participants’ gratitude ratings.” from Wikimedia Commons. Source article here.

“Neural correlates of gratitude. Medial Prefrontal activity correlating with participants’ gratitude ratings.” from Wikimedia Commons. Source article here. Gratitude activates the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). These brain regions are also involved in attention, emotional awareness, and social activity. They are also, not surprisingly, activated by prayer and mindfulness meditation.

I began this week with awe because I think awe is a more reliable path to gratitude than good fortune. Good things may happen for us or to us, and we may feel fortunate or happy without feeling particularly grateful. Gratitude comes from regarding more and more of what comes to us as a gift, and for me, the first gift is simply that I’m here. I am conscious. That I can experience anything at all is a gift. From my awareness, I can work my gratitude outward to the rest of the world. I can also be grateful to the giver—whoever or whatever she is.

Another author who has been my teacher in gratitude is Robin Wall-Kimmerer, a Potawatomi botanist and essayist who wrote Braiding Sweetgrass. She describes a version of the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address, a liturgy in which people take turns thanking each other, the Creator, Mother Earth, waters, fish, plants, animals, and so on. At the end of each stanza, the people say, “Now our minds are one.” The act of deliberately giving thanks in community bridges human differences and makes one voice out of many.

In the same way that my consciousness expands to include other people, our shared gratitude connects us as a community. We are not just a collection of individual minds: our minds are one.

I’m reminded of the sacrament of the Church: Communion, or the Lord’s Supper. The liturgy for it is called The Great Thanksgiving. It is a summary of the events of the Bible with the climax being Jesus’s last meal with his disciples. In that moment he held up a loaf a bread and said, “This is my body, given for you.”

It is fitting that his first cradle was a feeding trough, which we call a “manger.” Manger is a French verb meaning “to eat.” Our life, our eating together, and God’s incarnation and mission are all part of the same gift.

The Christmas story prefigures the Last Supper. The whole of Christ’s incarnation, God’s self-giving love, is reflected in this moment like a prism with many facets. We see this outpouring of God’s grace from many different angles, and I am overwhelmed on Christmas Eve with awe and gratitude.

Prayer: Thank you, thank you, thank you. Amen.

December 23, 2024

Week 4, Day 1: Awe

For the joy of ear and eye,

for the heart and mind’s delight,

for the mystic harmony,

linking sense to sound and sight;

Lord of all, to thee we raise

this our hymn of grateful praise. (“For the Beauty of the Earth,” by Folliot S. Pierpoint, 1864)

Sombrero Galaxy, Hubble Space Telescope. From Wikimedia Commons

Sombrero Galaxy, Hubble Space Telescope. From Wikimedia CommonsBecoming conscious is not an achievement: it is a gift. In the fourth week of this Advent-Epiphany devotional, I would like to turn to examine these gifts and gateways of consciousness.

In most of our daily life, we are barely conscious. We are unaware that our brain is actively working to keep continuity in what we see and hear until we are confronted with an illusion that makes us question our senses. We emote and act without thinking, relying on millions of years of conditioned reactions and a lifetime of programmed habits. We believe the stories we tell about ourselves. These are all ways we function without being conscious.

It isn’t “wrong” to move through a day this way. It’s natural. We can’t be conscious of our unconscious processes all the time: If I were to pay attention to how I’m walking, for example, it would suddenly become difficult to keep my balance or put one foot in front of the other. It’s easier to hand off this task to the unconscious part of my brain that makes walking feel normal. My unconscious brain is fast and efficient. My conscious brain is slower and more deliberate.

But life becomes much richer when I set aside time to become conscious, to marvel during mindfulness meditation at the way this body breathes all by itself, or to wonder at how my visual system creates color from chemical reactions in my retina. If I take time to notice, the act of noticing itself becomes a profound mystery, as the hymn above says. Neuroscientists are still discovering the “mystic harmony linking sense to sound and sight.” When I take time to marvel at consciousness itself, I find myself in awe.

Awe is a doorway into consciousness, helping us become more aware. Keltner and Haidt (2003) suggest that awe includes 1) a sense of vastness and 2) a need for accommodation. “Vastness” can be the experience of something big (like the Grand Canyon) or majestic (the musical sweep of a symphony) or even the presence of a beloved person or celebrity. This second experience, accommodation, relates to what my colleague Melissa Scott calls “right-sizing” (which I mentioned in an earlier post). We have to adjust our cognitive framework to fit new information. Sometimes this right-sizing means I see myself and my problems as much smaller. Sometimes it means feeling the gaze of God on me, as if I were the only one in the universe. We may feel simultaneously humbled and beloved.

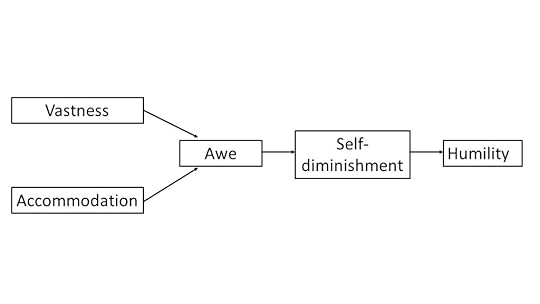

Appraisal tendency framework applied to awe (Stellar et al., 2017). From Wikimedia Commons

Appraisal tendency framework applied to awe (Stellar et al., 2017). From Wikimedia CommonsIn religious practice, we try to create such moments in worship with music, words, and ritual. I often feel such awe during a Christmas Eve candlelight service. We can also experience it in nature, although “chasing” awe in any setting can leave us feeling underwhelmed. I believe with practice or insight, we can also experience awe in very mundane moments. Thich Nhat Hanh talks about mindfully washing dishes and thanking them for their service.

The Christmas story evokes this kind of awe with the juxtaposition of highs and lows, divine and mundane: God as a baby in a feeding-trough. Angels appearing to shepherds. Ancient prophecies side-by-side with the frustration of finding a room in a crowded city.

And just as we often hear calls to “make Christmas last all year,” I think it is good to go into Christmas deliberately holding the door open for awe, letting ourselves become porous, so that we can be brought into a deeper consciousness of the mystery of God and of our own consciousness. Psychopharmacologist Roland Griffiths liked to ask, “Are you aware that you are aware?” We have the opportunity in Advent and Christmas to experience not only God’s incarnation, but our own.

Prayer: Awesome God, strike us with awe. Let us feel a deep reverence for all life and all experience.

December 20, 2024

Week 3, Day 5: Beyond the Self

But Moses said to God, “If I come to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” He said further, “Thus you shall say to the Israelites, ‘I am has sent me to you.’” (Exodus 3:13-14)

Moses and the Burning Bush, by Richard Simon, from Wikimedia Commons

Moses and the Burning Bush, by Richard Simon, from Wikimedia CommonsRene Descartes’ most famous quote is “I think, therefore I am.” His thought experiment involved questioning his perceptions of the world until he came to something he couldn’t deny: in order to have thoughts, there must be a thinker. There is an irreducible “I.” But consciousness is so slippery that researchers question even this “self-evident” truth. The thinking brain is less like an “I” and more like a committee!

In this series, I’ve been following a trail about consciousness: I am not my perceptions (week 1). I am not my thoughts or behaviors (week 2). I am not the story I tell myself about myself (week 3). What am I, exactly? What is this thing that believes it is thinking and experiencing?

Is it possible to have consciousness without a self at all? To experience “pure consciousness?” Some experienced meditators and psychedelic psychonauts describe such a state, where the self disappears and we feel connected to all things. We can use a magnetic field (fMRI machines) to look at brain activity and see that there are places in the brain that get quiet when people have such experiences. These brain systems maintain a separation between “I” and others and the rest of the world. With regular meditation, I can train these brain systems to relax.

Some refer to this experience as “ego death,” and report a variety of benefits from it: an increase in the feeling of awe at simple things; an ability to re-author the story I tell about myself; an enduring or residual feeling of connectedness to the universe and community of all living things. The “death” itself can be terrifying and disorienting, and it can lead to adverse effects for both meditators and psychonauts. (I have to point out that I’ve met more than a few meditators and psychonauts who’ve experienced “ego death” who have grandiose egos.)

A lot of psychotherapy involves helping people to understand that you are not your thoughts. Thoughts emerge from the matrix of your firing neurons, and then they subside. We can sometimes be fooled into believing whatever we think: “Nobody loves me,” “It’s pointless to try,” and so on. Sometimes it be difficult to divest from these thoughts because as false and painful as they are, they maintain a consistent sense of self. Losing the self can feel like death.

I consider God’s own name to be an affirmation of pure consciousness: “I AM.” God is the one in whom we live and move and have our being, and there is nothing outside this “I AM” which is separate from God. Moses the shepherd has a revelation of God’s name as he stands in front of a burning bush. There’s a similar revelation of God’s character as shepherds kneel beside the manger. The Christmas story describes a bridge between the flame and the breathing infant opening eyes on the world for the first time.

Prayer: Great I AM, I barely know what I am, but I long to know you better.

December 19, 2024

Week 3, Day 4: Expanding the Self

…what are humans that you are mindful of them,

mortals that you care for them?

Yet you have made them a little lower than God

and crowned them with glory and honor. (Psalm 8:4-5)

Mask Shop in Lome, Togo, by Philip Nalangan, from Wikimedia Commons

Mask Shop in Lome, Togo, by Philip Nalangan, from Wikimedia CommonsAs we go through life, our sense of self continues to expand and change. We may identify with our roles (“I’m a sibling, grandparent, citizen”) or our job (“I’m an architect, plumber, pastor, activist”) or our goals, values, and personal projects (“I’m just trying to be happy”).

We might grieve the loss of a job or a role and feel like part of our self has gone missing. When a family member dies, we may grieve the loss of a loved one, but also grieve the loss of who we were in relation to that person. If we lose a job or a career window closes, we may feel unmoored. As I’ve shifted from being a full-time pastor to bivocational counselor, I’ve had to adjust my own sense of self and mission in the world.

In our normal everyday life, we take our sense of self for granted. We look through it, rather than at it. Like our perceptions and automatic reactions, our self becomes part of our consciousness rather than something we actually notice.

A healthy sense of self has to be both stable and flexible. If we live long enough, everything about us will change: body, family, groups, beliefs, roles, and jobs. Some of those changes will be in our control, but many will not. We know intuitively that we need a self, a core, a set of values or a “north star” that doesn’t change with circumstance.

Donald Winnicott was an English psychoanalyst and developmental theorist who fleshed out this idea of “true self” and “false self” in the 1950’s and 60’s. He used them to describe the way we often protect our true needs and feelings by wearing a mask. He believed that a child needs “good enough” parents and opportunity to play to develop the creativity and core identity that would let them have a stable, flexible sense of self.

Certain areas of the brain play a crucial role in maintaining a sense of self. The ventral medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) seems to help maintain a sense of self through time. A cluster of several regions call the default mode network (DMN) creates a narrative about self. The DMN can also get caught in a negative loop of worry or rumination, and shifting its storytelling patterns is part of treating depression and anxiety.

I believe the story of the incarnation has the power to shift our story about the self. By slipping into a body and becoming a self that included but also transcended his job as a builder, his beliefs as a Jew, or his role as a son, God-in-Christ raises questions about our own sense of self. As various layers of the self are stripped away, we begin to understand that our primary identity is simply this: Beloved.

Prayer: Creator, what are human beings that you are mindful of them? What am I? Only your love makes us real. Amen.

December 18, 2024

Week 3, Day 3: Self as Believer

“But these are written so that you may continue to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:31)

Annunciation from 13th century Targmanchats Gospel, from Wikimedia Commons

Annunciation from 13th century Targmanchats Gospel, from Wikimedia CommonsOur sense of self begins very concrete, but then becomes more abstract over time. As children, we tend to think of “me” as “my body,” but as we enter adolescence we begin to think of the self as a member of a group. And as we move through adolescence into young adulthood, our brains continue to develop the ability to think abstractly. Our sense of self becomes more abstract as well. Some of us identify the self with our beliefs.

This is why churches who want to perpetuate themselves have youth programs. Research into belief formation has shown for decades that most of our core beliefs and identities are well established by the time we are in our early twenties. People who have not become Christians by the time they are young adults will likely never become part of a church. The proportion of new converts drops sharply after humans reach adulthood.

I’ve been in the church business long enough to understand that the most successful conversion efforts focus first on belonging (group identity and safety), and then believing. Folks who try to argue atheists into becoming believers (this kind of argument is called “apologetics”) rarely succeed; they really only reinforce their own beliefs and group identity as they experience rejection and derision from “outsiders.”

I’m using the word “believing” here to mean adopting a philosophy of the world and how it works, or learning to trust in certain belief systems. Most of us cobble together a worldview based on our own experiences, received wisdom from our communities and groups, religious rituals and traditions, and spiritual intuitions. We come to identify the self with these worldviews: “I’m a Christian,” or “I’m spiritual but not religious,” or “I’m an anarchist,” or “I’m a libertarian.” It can be both a way of seeing the world and a theory of how to change it.

Becoming conscious means becoming aware of these beliefs, both the explicit ones we can put into words and the implicit ones that we may find more difficult to express. In the same way that optical illusions make us aware of the effect of our perceptions on our own consciousness, we often only become aware of our beliefs when something challenges them. Some core belief of ours runs up against reality, or a contradictory story, and we have to make a choice of whether to hang on to the old belief or adjust our way of seeing and interpreting the world.

Belief is an important part of our identity. It connects us with our groups and gives us a framework for understanding our place in the universe.

David Benner in Spirituality and the Awakening Self describes this process as ever-expanding circles of self-understanding. Yes, I am a body, but I’m more than a body. I’m an American, but I’m more than my nationality. I’m a Christian, but I’m more than my religion. Some belief systems find this personal growth threatening, so they develop belief systems to put the brakes on the expansion of the self. Questioning old beliefs is perceived as backsliding or as dangerous to one’s salvation.

Yet at the heart of a belief in God is an understanding that we can never fully grasp the infinite. It is idolatry to confuse my beliefs about God with who God actually is. And when our beliefs become more important than our neighbor’s freedom and well-being, that’s when religious persecution begins. When we are most honest with ourselves, our beliefs are really a best-guess or a wager.

I see the Christmas story not so much as something to believe in, like a set of doctrines about God or Jesus, or the reality of the virgin birth and choirs of angels. I see it instead as something to believe through, or a story that stretches belief, that makes us question the binaries we invent between human and divine, power and powerlessness. It’s meant, I think, to push us toward an encounter with God-in-the-flesh.

Prayer: Lord, where beliefs as doctrines fall short, help me to trust in something that cannot be put into words. I believe; help my unbelief.

December 17, 2024

Week 3, Day 2: Self as Group Member

“But the people refused to listen to Samuel. “No!” they said. “We want a king over us. Then we will be like all the other nations, with a king to lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles.” When Samuel heard all that the people said, he repeated it before the Lord. The Lord answered, “Listen to them and give them a king.” (1 Samuel 8:19-22)

Derek Jensen, “Youth Soccer in Indiana,” from Wikimedia Commons

Derek Jensen, “Youth Soccer in Indiana,” from Wikimedia CommonsAs a toddler, we may have a sense of our self as a body, but as we grow older, we come to identify more with groups. This begins to happen in late elementary school and accelerates as we go through puberty. As our brains and bodies change, the opinions and dynamics of our friends come to matter more to us than our primary families. This is a natural part of human development and it’s part of what has kept the human species going over many eons.

Our ancestors survived only by being part of groups. Individual humans are weak and susceptible to predators, but humans in groups could strategically hunt and gather. We could coordinate action in a way that benefitted the tribe. Child-rearing, which is far more labor-intensive for humans than other mammals, was much more successful in a healthy community.

As we grow in other-awareness and group awareness, self-image becomes important to us. We develop the capacity to imagine ourselves through others’ eyes. For some of us, this shift in awareness is profoundly de-centering and traumatic, especially when it involves bullying, rejection, and miseducation into the values of mass culture. Our self-image is wounded; some of us see ourselves through fun-house mirrors, grossly distorted and worried about our bodies, reputations, or social position in a group. This is why so much therapy for trauma focuses on our memories of childhood and adolescence.

But if all goes well and our socialization into larger groups is successful, we may experience rites of passage and a sense of belonging. We may find “chosen family” and friendships that affirm us for our unique skills, values, and strengths. As I’ve heard more than one therapist say, “the best healing of trauma happens in a healthy community.”

Becoming conscious as a human also means becoming conscious of others, recognizing our dependence on the generosity and reciprocity of other human beings. Our self-awareness expands to include our group identities and other identities. Feeling like we belong and that others wish for our well-being is important for our thriving.

And yet as important as this expanding sense of self is to the growth of our consciousness, it can also become an obstacle. Our group is not the whole world. We can get stuck or limited in this self-as-group-member phase, fixated on our belief in the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves or our tribes. We become partisan, cultish, or cliquish. Our consciousness gets co-opted by powerful group stories and we lose an awareness that these are just stories. It can cause people to develop misguided loyalties or compromise their values in order to conform to the group.

Much of the Hebrew Bible is a story about group identity, both its good sides and its bad. God’s message to Israel was often, “You are my special people, but you are not my only special people.”

I talked about optical illusions in the first week, but I want to point out that this sense of self-in-community can become a narrative illusion. Group consciousness and our sense of belonging can be helpful or harmful, depending on the group and how deeply we believe the stories we tell ourselves.

Prayer: God-in-Three, we recognize in you the origins of community. We ask for discernment and wisdom in navigating our different roles and group belonging. Amen.

December 16, 2024

Week 3, Day 1: Self as Body

“I wouldn’t be caught dead without a body.” – W.H. Auden

“I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made…” – Psalm 139:14

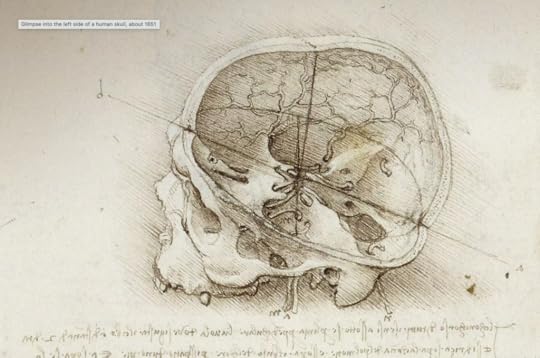

Leonardo DaVinci’s anatomical drawing of a skull, from the Max Planck Institute

Leonardo DaVinci’s anatomical drawing of a skull, from the Max Planck InstituteIn week one I talked about perceptions and how they impact our consciousness. In week two I talked about our automatic responses. This week I’m going to address another aspect of consciousness: our self-awareness.

In our earliest experience of consciousness, there is hardly any “self” to speak of. Freud called it the “oceanic feeling,” the sense that you are connected to everything, like an unborn baby in the womb. Even after birth an infant, he said, has little sense that she is distinct from her mother. There’s simply a need, like hunger; a cry for attention; and a response, like a breast. Freud theorized that this “oceanic feeling” of connectedness, this inability to distinguish self and other, is at the heart of religious mystical experience, and reflected a desire to return to this naïve, connected state. (Freud was not a fan of religion).

I’m not sure Freud was correct about all that. Research on the neural development of infants shows us that their mirror neurons start working only a few days after birth. Mirror neurons allow them to imitate facial expressions and respond to the emotions of people around them. They begin developing self-other maps with a week or two. While they may have a sense of connectedness, they start to form impressions about the character of other actors in their environment before they even have words.

Researcher Paul Bloom theorizes that babies have a sense of fairness and morality even before they’ve been taught about these things. When babies watched a cartoon of abstract shapes helping or hindering each other, they showed a preference for the helpful shapes over the unhelpful ones. Fairly early in our lives we develop a theory of mind and the foundation for what will become our ethics.

I appreciate David Benner’s understanding of our developing identity in his book Spirituality and the Awakening Self. He suggests that as infant humans gain control of their bodies, they come to understand the self as a body. “I’m in here,” inside my skin, and “the universe is out there.” We develop the idea that this self is perceiving the world from behind our eyes.

As we go through life, Benner continues, our sense of self enlarges: I am a body, but not just a body; I’m also part of a group. But I’m not just a member of a group; I am also my memories and emotions; I am my role (a parent, a sibling); I am my beliefs (a Christian, a Jew, an atheist); I am my job. A healthy sense of self incorporates these things, but also realizes that I am more than all of them, and I’m more than the story I tell myself about myself.

A sense of self, a location for our consciousness, forms the foundation for everything else. We are each incarnated or enfleshed in such a way that it is difficult to imagine having a consciousness without a body. Our most primal senses of bodily touch and smell communicate to the infant brain, “you are safe.” This closeness is so important for human thriving that babies who do not get cuddled may simply die.

In the Christmas story, God enters human life as an infant—disoriented, bewildered, and with little sense of self. As the infant Jesus grows, he changes. In the incarnation, God demonstrates to humanity that the spiritual is also physical, and that love is meaningless without touch and care for physical pain and pleasure. God, the Great “I AM,” has a body.

Prayer: Divine Mother and Father, we give you thanks for these fragile, incredible, glorious, malfunctioning bodies. May we take the care of all of them, ours and others’, seriously. Amen.