Grigory Ryzhakov's Blog, page 3

November 27, 2014

12 New Russian Dystopian Books

At the moment, the world is fascinated with the film adaptation of the penultimate sub-chapter of the Hunger Games trilogy, Mockingjay. The YA dystopia has gathered an unprecedented popularity amongst adults too. Its theme of oppression and totalitarianism reflects our modern history, the states of North Korea or the Soviet Union are two examples. Russian authors produced finest dystopian novels over the recent decades.

Dystopian fiction is a rather novel but insanely popular genre. Human progress threatens to destroy nature with the advent of global industrialization, nuclear weaponry and other formidable things humans brought in. But perhaps the biggest impact on this genre had the Russian communism and European Nazism, dictatorships that keep terrifying the world. One could have thought that utopia/dystopia should be a well-represented genre in Russian literature. However, the list is rather small – we have Chernyshevsky’s What’s To Be Done, Zamyatin’s My, Strugatsky brothers’ and Platonov’s novels in the XXth century and that’s about it. The post-Soviet literature, freed from the state censorship, gave us a lot more gems, half of them are already available in translation, which means that this genre of Russian literature is what foreign publishers, and hopefully readers, want. I will start with a classical dystopian scifi, often dismissed by literary snobs as genre fiction for plebs. Yet, commercially these are one of the best exported titles in Russian fiction.

Dmitry Glukhovsky debuted with a post-apocalyptic novel, Metro 2033, that became a smashing best-seller in Russia in 2007 and later a very popular computer game. The book has since been widely translated. Its sequel, Metro 2034, was equally successful. The Metro Universe set in the post-nuclear Earth with the remaining mankind lurking in the dungeons, the biggest is Moscow Underground (metro). All the tube stations are like mini-countries, while the dark tunnels are darl places of chaos. In Metro 2033, One of the stations, VDNH, and maybe the whole mankind, are in danger, and the ordinary guy named Artyom has to travel across the entire Metro to save his people. In the sequel novel, another tube station, ironically named after the Crimean military base – Sebastopolskaya – became cut out of the main metro system. And as always the world is in need of another hero.

Dmitry Glukhovsky debuted with a post-apocalyptic novel, Metro 2033, that became a smashing best-seller in Russia in 2007 and later a very popular computer game. The book has since been widely translated. Its sequel, Metro 2034, was equally successful. The Metro Universe set in the post-nuclear Earth with the remaining mankind lurking in the dungeons, the biggest is Moscow Underground (metro). All the tube stations are like mini-countries, while the dark tunnels are darl places of chaos. In Metro 2033, One of the stations, VDNH, and maybe the whole mankind, are in danger, and the ordinary guy named Artyom has to travel across the entire Metro to save his people. In the sequel novel, another tube station, ironically named after the Crimean military base – Sebastopolskaya – became cut out of the main metro system. And as always the world is in need of another hero.

In his latest novel, The Future, recently translated into German, Glukhovsky has indeed touched the future of Europe. What if people became immortal? Would we become a happy society? Or it will be highly stratified society ruled by dictators? And what is the price that we’ll have to pay for immortality? Overpopulation. The Future is a gripping, passionate, adrenaline-packed and philosophical story, and ultimately it’s about love, powerful, unforgiving and all-forgiving. It’s a bona fide international block-buster, hands down.

Russia is big yet many books are based in Moscow or St Petersburg. And the reader loves exotic locations. How about the Ural Mountains famous for their precious stones, the land described in Bazhov’s fairytales.

Olga Slavnikova set her dystopian novel 2017 here, but called the Urals their ancient Greek name, Riphean Mountains. 2017 marks a centenary of the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. In Slavnikova’s novel the centenary’s merry celebration turns into another ugly and violent revolution. Yet this phenomenon of the cyclical Russian history is only a background to a love story. The main character Krylov is a historian and the precious stone enthusiast (Danila the Master in Bazhov’s fairy tales). His ex-wife is a capable entrepreneur owning a funeral business. Krylov’s new love, Tanya, the Stone Lady, is the antipode of Tamara. Skinny and ephemeral (Bazhov’s the Lady of the Copper Mountain). The plot of 2017 is full of twists, yet the prose is slow and exquisitely metaphorical. It is , by no means, an easy read, it makes you think about material and spiritual world and why people tend to choose one or the other. Krylov is man of both and Tanya and Tamara drag him into opposite directions. Love, treasure hunt, revolution, philosophy and beautiful writing, 2017 is an entertaining read that doesn’t patronise your intelligence.

Olga Slavnikova set her dystopian novel 2017 here, but called the Urals their ancient Greek name, Riphean Mountains. 2017 marks a centenary of the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. In Slavnikova’s novel the centenary’s merry celebration turns into another ugly and violent revolution. Yet this phenomenon of the cyclical Russian history is only a background to a love story. The main character Krylov is a historian and the precious stone enthusiast (Danila the Master in Bazhov’s fairy tales). His ex-wife is a capable entrepreneur owning a funeral business. Krylov’s new love, Tanya, the Stone Lady, is the antipode of Tamara. Skinny and ephemeral (Bazhov’s the Lady of the Copper Mountain). The plot of 2017 is full of twists, yet the prose is slow and exquisitely metaphorical. It is , by no means, an easy read, it makes you think about material and spiritual world and why people tend to choose one or the other. Krylov is man of both and Tanya and Tamara drag him into opposite directions. Love, treasure hunt, revolution, philosophy and beautiful writing, 2017 is an entertaining read that doesn’t patronise your intelligence.

Fazil Iskander is an Abkhazian writer, a classic of Soviet and modern Russian literature, whose writing is known for unparalleled humour and satire. His novella Rabbits and Boa Constrictors is a fairytale allegory of the Russian state, whose notorious figures are recognised in these rabbits, boas and anacondas. The allegory helps to dissect the psychology and the mechanics of the dictatorship state, with its bureaucracy, submissiveness of its inhabitants, – ‘their hypnosis is our fear‘, one of the rabbits realises. This books is a Russian cousin to Orwell’s Animal Farm.

Fazil Iskander is an Abkhazian writer, a classic of Soviet and modern Russian literature, whose writing is known for unparalleled humour and satire. His novella Rabbits and Boa Constrictors is a fairytale allegory of the Russian state, whose notorious figures are recognised in these rabbits, boas and anacondas. The allegory helps to dissect the psychology and the mechanics of the dictatorship state, with its bureaucracy, submissiveness of its inhabitants, – ‘their hypnosis is our fear‘, one of the rabbits realises. This books is a Russian cousin to Orwell’s Animal Farm.

In Anna Starobinets’s The Living the future world is like one organism where information is the biggest commodity. All the inhabitants are completely immerse din this virtual reality called Socio (an allusion to our modern day smartphones, web2.0 and Facebook). The living world is immortal and everybody is immortal and has a unique ID in this world. It doesn’t matter who is your biological ancestor, it is important who you were in your past life, before the Pause. No borders, religion, countries , nations – just The Living. But one day somebody is born without an ID, a treat to the Socio and The Living.

In Anna Starobinets’s The Living the future world is like one organism where information is the biggest commodity. All the inhabitants are completely immerse din this virtual reality called Socio (an allusion to our modern day smartphones, web2.0 and Facebook). The living world is immortal and everybody is immortal and has a unique ID in this world. It doesn’t matter who is your biological ancestor, it is important who you were in your past life, before the Pause. No borders, religion, countries , nations – just The Living. But one day somebody is born without an ID, a treat to the Socio and The Living.

Vladimir Makanin’s Escape Hatch is a novella juxtaposing two worlds – one is a fragile refuge of intelligentsia, existing in the form of an underground bunker, and the rest of the world is the overground city, devastated by wars and conflict, the escape hatch is all the connects them. The book reminds me of phrase, ‘an ostrich buried his head in the ground’. If we hide ourselves from the world, eventually they’ll be no way back. The narrowing escape root is a metaphor of a painful extinction of a beautiful animal who failed to adapt to the abruptly changing environment.

Vladimir Makanin’s Escape Hatch is a novella juxtaposing two worlds – one is a fragile refuge of intelligentsia, existing in the form of an underground bunker, and the rest of the world is the overground city, devastated by wars and conflict, the escape hatch is all the connects them. The book reminds me of phrase, ‘an ostrich buried his head in the ground’. If we hide ourselves from the world, eventually they’ll be no way back. The narrowing escape root is a metaphor of a painful extinction of a beautiful animal who failed to adapt to the abruptly changing environment.

Viral pandemics? Here’s Yana Vagner’s Vongozero, now available in French translation. It is story of a family struggling to survive in Russia crumbling in the deadly flu pandemic. The novel was initiated as a series of blog posts in LiveJournal, a popular social media network, and it’s definitely the people’s choice. Fancy a daunting and realistic thriller a la 28 Days later sans Zombies with a Russian setting, here you are. N.B. Do your vaccinations in time.

Viral pandemics? Here’s Yana Vagner’s Vongozero, now available in French translation. It is story of a family struggling to survive in Russia crumbling in the deadly flu pandemic. The novel was initiated as a series of blog posts in LiveJournal, a popular social media network, and it’s definitely the people’s choice. Fancy a daunting and realistic thriller a la 28 Days later sans Zombies with a Russian setting, here you are. N.B. Do your vaccinations in time.

Of course, the modern giant of Russian literature Vladimir Sorokin can’t be forgotten when it comes to dystopia, a genre he’s been writing in the recent decade. The Day of the Oprichnik portrays Russia in the 2027, the country looks like the military dictatorship of Ivan The Terrible, with Oprichniki (the medieval KGB) terrorising the population. The novel is written in a stylized prose mimicking archaic Russian, which adds to the political satire. On one hand, the absolute monarchy, xenophobia, self-rule of the Oprichniki, repressions are metaphorical glimpses into Russia’s various horrible eras, on the other – they are an ever-present part of Russia’s sociopolitical landscape. The horrible historical parallels emphasize the fact that Russia’s, in fact, never changed in its core and attitude to people.

Of course, the modern giant of Russian literature Vladimir Sorokin can’t be forgotten when it comes to dystopia, a genre he’s been writing in the recent decade. The Day of the Oprichnik portrays Russia in the 2027, the country looks like the military dictatorship of Ivan The Terrible, with Oprichniki (the medieval KGB) terrorising the population. The novel is written in a stylized prose mimicking archaic Russian, which adds to the political satire. On one hand, the absolute monarchy, xenophobia, self-rule of the Oprichniki, repressions are metaphorical glimpses into Russia’s various horrible eras, on the other – they are an ever-present part of Russia’s sociopolitical landscape. The horrible historical parallels emphasize the fact that Russia’s, in fact, never changed in its core and attitude to people.

The novel was followed by The Sugar Kremlin, a collection of short stories set in the same time. Both books are considered a dilogy, they have won prestigious awards in Russia and have been nominated for International Booker Prize in 2013. Sorokin’s latest book, Telluria, that is yet to be translated, continues the absurdist and satiric trend: it is set in the middle of the XXIst century and follows the fate of both Russia and Europe that were plunged back into dark medieval age. Orthodox communists and Crusaders, centaurs and cynocephals (dogheads), everyone’s mind is not on God’s Kingdom but the Republic of Telluria (aka Russia split into feudal bits) and its magic metal that brings happiness and unites the land.

Another giant of Russian post-modernist literature, Victor Pelevin has a couple of dystopia in his back-list. The Yellow Arrow is a railway-themed allegorical novella. The train, a metaphor of Russia, which encompasses the entire world for all the characters, goes towards a crumbled bridge. If Russia has ever known quiet periods, they were just ebbs, receding worries, before tsunami.

Another giant of Russian post-modernist literature, Victor Pelevin has a couple of dystopia in his back-list. The Yellow Arrow is a railway-themed allegorical novella. The train, a metaphor of Russia, which encompasses the entire world for all the characters, goes towards a crumbled bridge. If Russia has ever known quiet periods, they were just ebbs, receding worries, before tsunami.

T atiana Tolstaya‘s The Slynx is probably the most elegantly-written dystopia I’ve ever encountered. Tolstaya is the living master, the golden standard of Russian language. The world after nuclear apocalypse, most of technology, culture and language are wiped out. In a post-nuclear Russian village (called Fyodor-Kuzmichsk that once was Moscow) people may live like animals, and often look like ones with atavisms like horns and tails appearing among the folk, but the scariest thing is the Slynx, a forest-dwelling monster and a metaphor for fear of the unknown. The few books found after the Explosion are taken from people and are stored in the book depository, where Benedict , the main protagonist, works: he reads books and copies them by hand for preservation purpose, randomly, from children literature to specialised technical guides. He likes Olen’ka, another scribe working in the depository, and they get married. Olen’ka is a daughter of the Chief Sanitar, most powerful man in the village, so Benedikt is positioned as a successor. And here’s the plot starts to thicken.

atiana Tolstaya‘s The Slynx is probably the most elegantly-written dystopia I’ve ever encountered. Tolstaya is the living master, the golden standard of Russian language. The world after nuclear apocalypse, most of technology, culture and language are wiped out. In a post-nuclear Russian village (called Fyodor-Kuzmichsk that once was Moscow) people may live like animals, and often look like ones with atavisms like horns and tails appearing among the folk, but the scariest thing is the Slynx, a forest-dwelling monster and a metaphor for fear of the unknown. The few books found after the Explosion are taken from people and are stored in the book depository, where Benedict , the main protagonist, works: he reads books and copies them by hand for preservation purpose, randomly, from children literature to specialised technical guides. He likes Olen’ka, another scribe working in the depository, and they get married. Olen’ka is a daughter of the Chief Sanitar, most powerful man in the village, so Benedikt is positioned as a successor. And here’s the plot starts to thicken.

Reading a lot doesn’t mean understanding of what’s written. Benedict is unable to educate himself enough to see the world around him despite being obsessed about books, he still lives like a caveman. So people who govern and have access to all the information don’t necessarily preserve our culture.

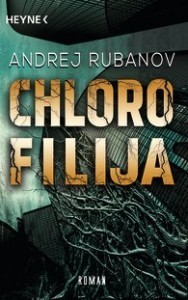

Andrei Rubanov‘s Chlorophilia, now available in German, stands out amongst its cousin novels about bleak future because of its inventive setting. The XXIInd century Moscow, where all the Russian population now lives, is plagued with giant green stems of an unknown origin that ascend for hundreds of meters overshadowing the old landscape. The pulp of the plant is edible and has invigorating/psychotropic properties. Poor people, underclass, junkies live on the ground, the more privileged you are the higher you reside, closer to the sun. The rich people from China, who rent Siberian land, occupy the top. Savely Herz, a journalist, secretly taking the highly purified stem for invigoration, has it all: a successful career, a beautiful woman and an apartment at high elevation. Yet, he’s about to find out things that will shake the country and threaten his own life. The book reminds me of The Day of Triffids, it’s a story of the man vs nature. It’s also a story of sin and atonement. The man uses nature the way he wants unaware of consequences or simply thinking he can outsmart everyone.

Andrei Rubanov‘s Chlorophilia, now available in German, stands out amongst its cousin novels about bleak future because of its inventive setting. The XXIInd century Moscow, where all the Russian population now lives, is plagued with giant green stems of an unknown origin that ascend for hundreds of meters overshadowing the old landscape. The pulp of the plant is edible and has invigorating/psychotropic properties. Poor people, underclass, junkies live on the ground, the more privileged you are the higher you reside, closer to the sun. The rich people from China, who rent Siberian land, occupy the top. Savely Herz, a journalist, secretly taking the highly purified stem for invigoration, has it all: a successful career, a beautiful woman and an apartment at high elevation. Yet, he’s about to find out things that will shake the country and threaten his own life. The book reminds me of The Day of Triffids, it’s a story of the man vs nature. It’s also a story of sin and atonement. The man uses nature the way he wants unaware of consequences or simply thinking he can outsmart everyone.

Well, we can only outsmart ourselves.

November 13, 2014

Interstellar and Contact: Love and Singularity

Christopher Nolan’s new space opera Interstellar has recently hit silver screens all over the world. What makes it so much talked about and special?

The Earth is doomed: an unknown blight kills one food crop after another and dust storms become the norm. The mankind switches back to the agricultural society abandoning science. An ex-NASA engineer Cooper is entrusted to head a space mission to a possibly habitable planet (through an enigmatically appeared wormhole) to rescue the humanity.

The film delivers at the plot level as a suspenseful space extravaganza and as a philosophical saga. Hans Zimmer’s awe-inspiring score augments the visual awesomeness of the gargantuan waves on Miller’s planet and the frozen clouds of Mann’s. Often critised as corny are Cooper’s co-pilot and astrophysicist Amelia’s words

‘Love is the only thing that transcends time and space’

reminded me of Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev’s

‘Love covers everything, hopes and believes everything, overcomes everything. Love never ceases’

They are not just a sentimental outburst, they provide the symbolic foreshadowing to Cooper’s revelation in the climax.

Interstellar also shines in science communication. Nolan’s co-writer Kip Thorne, a theoretical physics, infused into it current scientific ideas that he further explained in his new book, The Science of Interstellar.

In the final leap where all plot and thematic lines converge, Cooper ends up in the epicentre of a Gargantuan blackhole (which makes me think about Pantagruel’s whereabouts), a gravitational singularity, beautifully realised as a tesseract with time being a fourth spatial dimension.

a tesseract

Here the plot end meets its beginning in a Moebius strip twist, lyrically revealing the identity of a ghost who’d sent Cooper on a journey and separated him from his daughter Murph in the first place.

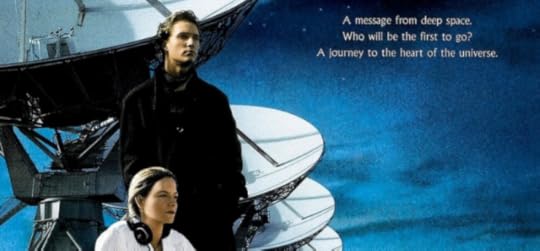

Contact, the 1997 film poster

The father and daughter relationship is also explored in Carl Sagan’s scifi epic, Contact (1997), directed by Robert Zemeckis and starring Jodi Foster and Matthew McConaughey (the lead in Interstellar). Dr Elleanor Arroway , a SETI scientist detects a signal presumably sent by some extra-terrestrial life. Further communication results in building a space-travel apparatus, acting like a wormhole in Interstellar, which sends Elleanor to an unknown part of the Universe where she meets her father. Sagan writes in Contact,

‘For small creatures such as we the vastness is bearable only through love.’

And so wrote Dante in The Divine Comedy before him in the XIVth century,

‘Here vigour fail’d the tow’ring fantasy:

But yet the will roll’d onward, like a wheel

In even motion, by the Love impell’d,

That moves the sun in heav’n and all the stars.’

Maybe Nolan is not the ‘cheescake’ afterall, he simply respects the tradition.

November 1, 2014

The Pillowman by Martin McDonagh. Review

The Pillowman cast photo by pjgeller (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

On the Halloween night I went to see a new adaptation of Martin McDonagh’s play The Pillowman at Oxford Playhouse Theatre, a black comedy that swept me off with its masterful accomplishment. Well, I expected no less from this amazing screenwriter and film director who created In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths.Thrillers that involve murder, child abuse and violence are not my cup of tea, but there’s a tender compassionate side to The Pillowman that has completely won me over. The peculiar thing about this adaptation is that the two main characters are played by female actors, which magnifies the dramatic effect of the play in my opinion.

In a fictitious totalitarian state a short story writer Katurian is being interrogated by two cops who find bodies of children killed in an exact way as in Katurian’s disturbing stories. Katurian’s mentally-challenged brother, Michal, is also suspected as the writer’s accomplice, especially when cops find children’s toes in Katurian’s house and Michal admits executing the murders. Cops need both of them to come clean before Katurian and Michal can be executed.

As the plot thickens, we hear many Katurian’s stories, we see devastating secrets of the cops’ and the brothers’ past being unveiled.

Everything here is a work of genius, a masterclass for new writers. Each of these eloquent stories shine on their own, yet an indispensable element of the entire play.

The central theme here is the psychological impact of childhood trauma on personal development. If we are hurt and abused as children, does it mean we will hurt others as adults? We find this issue discussed here on several levels, in the dynamics between Katurian and his brother, his parents and the cops. There’s also a different, twisted side to this theme explored in the center-piece story of The Pillowman where a child murder shown as a ’prophylactic’ euthanasia saving a person from the future unhappy life terminated by suicide. Another theme here is that things done out of compassion aren’t always good. And finally, there is a discussion important to McDonagh himself about art exploring the dark side of humanity – does it need to be destroyed if it can make people hurt each other?

The Pillowman will remain with me for a long time, as a beautiful piece of writing and thought. I’m definitely getting the book for my library. Every word here matters and that’s what any writer should strive for in his stories.

Various versions of The Pillowman can also be viewed on Youtube. A not-so-sweet Halloween treat for art lovers.

Watch how this Oxford adaptation was prepared

October 23, 2014

GLAS – New Russian Writing in English

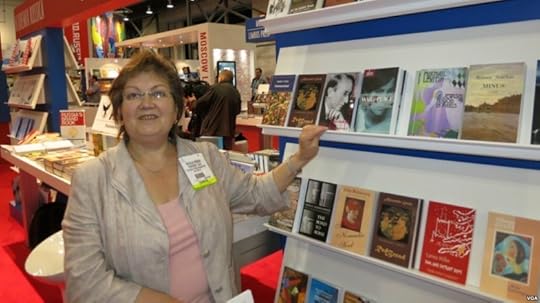

Natasha Perova, the founder of Glas

Today I am thrilled to present you Natasha Perova, whose titanic efforts resulted in many English translations of great contemprorary Russian books becoming available for international readership. Natasha helped to show the world that Russian literature not only survived collapse of the Soviet Union, it is very much in blossom.

Natasha, what prompted you to become a publisher of Russian books in English translation?

In 1988, I was invited to edit Soviet Literature magazine in English translation (it was already perestroika times when formerly banned names were returning to the public, sometimes posthumously) and it was then that I practically “discovered” Russian writing for myself and fell in love with it. I felt I ought to share this newly-found treasure with people from other countries who only knew our 19th century classics.

Unfortunately the magazine was soon closed down and I started GLAS. My original intention was to publish samples from our best writers and try to interest publishers in the UK and US in doing the full versions. I thought the world will gasp with admiration but it did not happen very often. Both publishers and the public were slow to appreciate contemporary Russian literature. A good example is a recent review of Anatoly Mariengof’s “Cynics” that we published back in 1991 (after the review we reprinted it as an e-book.)

How do you choose what to publish? Do authors or Russian publishers submit their suggestions or you pick the titles first?

Initially I wanted to embrace the entire literary scene and published mostly anthologies. There was too much good material: contemporary texts and rediscovered classics from the 1920s and 30s. But young authors and critics in those days were enthusiastically helping with advice. I trusted my intuition and have never regretted a single publication – each of them is interesting and important in its own way.

My intention was not to make money on books but to make available the most interesting and vibrant texts to the reading public abroad. Russia was in vogue at the time and we managed to sell enough books to publish the next title.

I’ve been reading avidly all this time and each of my choices is a considered one. I only wish I had funds to publish all the books I admire.

I see that you have published several books that have a common theme: women’s prose or Russian communist revolution of 1917. Are there any sub-genres of Russian literary fiction that are particularly overlooked by foreign publishers in your opinion?

In imitation of the English-language magazine GRANTA our collections of diverse writers and poets were grouped around a unifying theme (e.g. revolution, fear, childhood, women’s views). Later issues have focused on the work of a single author in order to give the reader a better sense of his/her overall oeuvre. For three years we published a sub-series of young authors (the Debut Prize winners).

Many brilliant names have been overlooked by foreign publishers, but as for genres, they are the same everywhere, only the material and the settings are Russian. So basically, if you are interested in Russia and know at least some basic facts about it then you’ll enjoy and understand contemporary Russian fiction. I don’t know what Russia can do to win the former interest back.

You’ve published several young authors’ books recognised by the Debut literary prize. How can they compete with established masters of Russian prose for readers’ attention?

In the last few years a whole constellation of successful bright authors has come onto the literary scene. We should all read them if we want to know how they see their country and what they might do to it. They have a sober look on life but pronounce no judgments, they notice a multitude of details, and provide memorable portrayals. Most of them live in the provinces where we are unlikely to go, but we can read about those exciting places in their works – it’s like a virtual literary journey.

What are the most popular titles amongst those you’ve published? What’s the reason behind their popularity?

The most successful titles were always a surprise to me. For example, Nina Lugovskaya’s “Diary of a Soviet Schoolgirl”, Arkady Babchenko’s witness accounts of his war experiences, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky’s newly discovered stories from the 1930s, Sinyavsky’s “Ivan the Fool”, “The Portable Platonov”, collections of women’s writing, and Michell Berdy’s “The Russian Word’s Worth”, which is a book about today’s Russia described through its language.

What do you plan to publish next?

Right now I had to put Glas on hold because due to the falling sales and rising prices I can no longer save enough money to continue publishing books without external support (which I have never had — I’m not eligible for any grants either in Russia or abroad.) But we have created an extensive database of translated texts which Slavists can use for teaching Russian literature and publishers can use for publishing ideas. I’ll continue promoting new writers as a literary agent and, who knows, help may come out of the blue some day.

But I must say that we have collected enough praise along the way to convince me that we have done a good job and it is only my lack of business skills that prevented me from turning this project into something more durable.

Thank you for this honest interview, Natasha. If you allow me to say – considering the enormous amount of books translated and published by Glas, you definitely left a durable mark . Now it is up to readers to discover these translated new Russian books. And bloggers like me will be helping to spread the word.

October 17, 2014

The Pillar of Russian Poetry: Mikhail Lermontov – 200th Anniversary

A portrait of Mikhail Yurievich Lermontov by Pyotr Zabolotsky, painted in 1837.

This week the world celebrates the 200th birthday of a great Russian poet, Mikhail Lermontov, who had Scottish roots, so it’s a cultural hallmark in Russia as well as in the UK.

Lermontov’s poetry and prose is in the school literature curriculum in Russia. Practially every grown-up Russian has read Lermontov’s masterpiece novel, A Hero of Our Time, which you can download for free from the Gutenberg Project website.

The novel is centered on a Byronic hero, a military man called Grigory Pechorin, who travels around Caucasus leaving a trail of broken hearts and taken lives. If you are looking for superb prose, this novel is an embodiment of it. I can’t recommend it enough.

At school, I was fascinated with this book. I had even written an essay on it as a part of the university entry exam (when I admitted to Moscow State Uni). To think of it, 200 years later and Caucasus still remains a gunpowder barrel.

Not that many people know that Lermontov enjoyed drawing as well as writing, landscapes were his favourite.

A peasant under a tree.M. Lermontov, ink, 1832-1834

For those, who would like to learn more about him, Russia Beyond The Headlines has published a series of articles on Lermontov, including an interactive map of his travels in Russia.

I’d like to finish with one of Lermontov’s poems,

The angel was flying through sky in midnight,

And softly he sang in his flight;

And clouds, and stars, and the moon in a throng

Hearkened to that holy song.

He sang of the garden of God's paradise,

Of innocent ghosts in its shade;

He sang of the God, and his vivacious praise

Was glories and unfeigned.

The juvenile soul he carried in arms

For worlds of distress and alarms;

The tune of his charming and heavenly song

Was left in the soul for long.

It roamed on earth many long nights and days,

Filled with a wonderful thirst,

And earth's boring songs could not ever replace

The sounds of heaven it lost.

© Copyright, 1996

Translated from Russian by Yevgeny Bonver , October 1995.

October 11, 2014

Magic Realism in Russian North. Stepan Pisakhov’s Senya malina

Traditions of magic realism in Russian literature probably have roots in its pagan culture. There’s a contradiction here you may say. Russia is supposed to be dominated by the conservative Orthodox Christianity, the country was baptized over a millennium ago.

Yet paganism never seized to exist in Russia. Kolyada, svyatki, Ivan Kupala are examples of Russian pagan holidays that have similar counterparts in many European countries. Nowadays Russians may not recognise multiple Gods as they used to do, but they still live life full of pagan traditions and superstitions.

Another reason for Christianity failing to completely own Russians is the oppressive nature of the Orthodox Church institutions. Russian Church has always been an ally of the ruling class (except for the Communist era) to control simple people. There used to be a church tax, where peasants were obliged to give ten percent of their income to the church. The male Church staff are often portrayed as fat rascals in Russian folklore.

Contrary to that, the real God in Russia has been Nature. Folk tales give natural objects, plants and animals, rivers and mountains, celestial bodies or wind human-like or magical properties. Perhaps, this was the way to cope with the harsh reality. Russians have always assumed the world around them is magical and full of secrets.

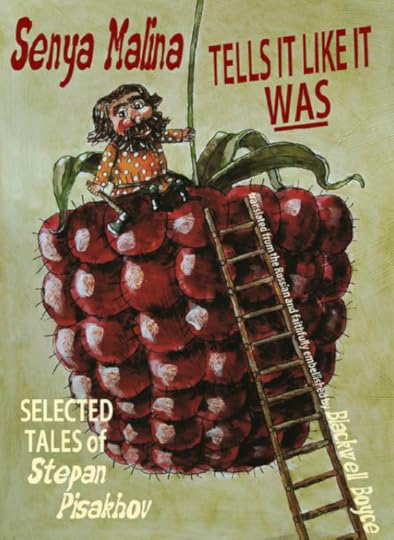

Now the English-speaking audience has an opportunity to explore this part of Russian culture. Today I present you Stepan Pisakhov’s Senya Malina Tells It Like It, beautifully translated into English by Blackwell Boyce.

Stepan Pisakhov (1879-1960) was a story-teller and a landscape painter from the Pomorie region of Northern Russia. Pomorie is the south coast of White Sea with a capital in Archangelsk. Northen Dvina River flows across this land, passing the village of Weema (nowadays Uyemsky) where most of Malina’s stories are set.

Senya Malina is a commoner famous for his imaginative tales filled with satire mostly targeting local civil workers (byurokraty) and the Orthodox Church. Malina’s tales spread not only amongst locals but also in the capital, the city of Archangel.

Senya Malina lives in Weema with his wife and a dog, yet his life is not ordinary. He can run on the water, fly home on a cloud, or cover many versts (miles) from Weema to Archangel just using one step of his stretchable giant leg. In his absurd humorous stories he encounters major opposition in the face of a local priest called Sivoldai and the bureaucrats of Archangel whom he relentlessly humors.

Bureaucrats as a species have such weak spines they need their uniforms to prop them up. It’s always puzzled me where they found the strength to laugh at us peasants and common folk.

Stephan Pisakhov’s stories in this book are accompanied with colorful illustrations made by Dmitry Trubin, which nicely complement Senya’s stories. Pisakhov’s writing, though being a part of the Russian folklore, reminds me of Fables written by a Russian classic Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, popular stories in the same genre of magic realism known for their grotesque portrayal of Russian life and political satire.

The most amazing thing about these stories to me is that a century had passed but the Russian life remained the same. Our society is still ruled by the thieving ’burokraty’ allied with the Russian Orthodox Church, both serving a never-ending inspiration for satirical comments and public escapades like the Pussy Riot’s prayer. Many Russians are devout Christians and they know that their faith is not the same as the Christian Church, an institution. As evidence to that, Archimandrit Tikhon’s The Unholy Saints has been a bestseller in Russia for several years now. I make a mental note to introduce you to Russian Christian fiction in the future. For now, you can enjoy Senya Malina’s stories in English.

September 30, 2014

Jeno Marz: Space, Aliens and Writing

Many writers have degrees in humanities, yet some, including me, have technical jobs. Today, I welcome at my blog a science fiction writer from Latvia, Jeno Marz.

Many writers have degrees in humanities, yet some, including me, have technical jobs. Today, I welcome at my blog a science fiction writer from Latvia, Jeno Marz.

Jeno, your professional background is engineering, a very technical occupation, yet you’re artistic. What inspired you to become a writer?

I’ve been artistic, specifically in drawing department, ever since I could hold pencils. I’ve been creating worlds and creatures for my own fun, but during the time I avidly started reading fiction (which was somewhere in middle school, the time I could buy whatever book I wanted), I realized that I should try putting my musings into written form. My mother introduced me to science fiction and my family had a huge library, but what interested me wasn’t classic lit. I devoured non-fiction about expeditions, adventures, world myths and ancient literature, geographical memoirs, popular science books, and anything in between. As a younger teen I was fascinated with magazines like Science and Life [Наука и Жизнь], Planet’s Echo [Эхо Планеты], Around the World [Вокруг Света] – I’m referring to this one http://www.vokrugsveta.ru/, and even gardening magazines. We had large gardens during that time, too. Fast forward past school graduation and I’m in the tech university, computer science and electronics engineering faculty [yes, math and physics aplenty!]. I’d say programming and engineering helped me to become a better writer. I’m a person of structure, so it comes naturally to me in everything I do. I never had issues with structuring my work. I can easily imagine the whole and its separate parts and how everything will fit together and what methods I should use. Character arcs, scenes, narrative arcs, theme exploration – I don’t plan those. They arise on their own once I know the story I want to tell. And that comes from the worlds I imagine, in great detail.

I know that you read graphic novels and watch anime, how does this influence your writing?

What do both these things have in common? Storyboarding. Clear visual structure. (Not to mention unique and lovely stories you won’t find anywhere else.) To some point movies and TV series are technically the same, but I watch these rarely now. I was in cinematic club in high school, I’ve watched, discussed, and written about a fair share of films—think Nosferatu, Seven Samurai, Psycho, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—and stopped watching movies with the advent of heavy CG era. I have to say I adore 2D animation (particularly Japanese and European, but not so much American) as much as I detest overbearing CG and 3D pseudohumans (the latter especially on book covers.) I’m a very visual person and if there was one thing I’ve learned from the abovementioned mediums, it is how to do scenes without delving into theory what a scene is. It’s not a good thing for a writer to say, but I’m not very savvy in the lit theory, and I don’t want to go there, I’m not really interested. All those scholarly definitions confuse me. I want to see what those are, not read about them. Graphic novels and animation allow me to observe stories in visual form and make my own conclusions. Reverse engineering, of a sort. I find it interesting to do. This habit didn’t come without a cost—I developed a writing style that resembles visual form storytelling. It might feel unusual, reserved and episodic to some readers, but on the whole the stories themselves are far from episodic.

People are important, they drive the story. Anything else stems out of that.

Your epic science fiction trilogy Falaha’s Journey is set in space and features an alien as a main protagonist. How did you come up with this idea for the Universe and the central character?

I find it interesting that people call my story ‘epic’. If you define an epic as a long narrative which concentrates on the fortunes of a great hero, who is normally often a king or a leader, or perhaps a great civilization and the interactions of this hero and his civilization with the gods; stresses heroes’ relationship with their fathers; has some form of nostalgia and glorification of bygone eras, then yes, the story definitely has the characteristics of an epic, unintentionally so. Other than that, Falaha’s Journey is a family story and a story about self-discovery. In space. If by the setting you mean alien cultures, then yes, these are important. Space as the physical setting arises naturally from the scales of my fictional cultures. I write character-driven fiction. People are important, they drive the story. Anything else stems out of that.

This Universe (called OS Universe, as in Operating System Universe) is an old idea, I’ve been developing it since 2001. The central character in this particular story appeared somewhere after I’ve been working with disabled children at the special needs daycare and medical center for over 9 months. I’m disabled myself, so this work was a bit unrelated to my tech background. This critical part of my life became a very valuable experience that subconsciously inspired the story’s main character. The world for her was already created for a different novel, Rjg, (still in the works), so the character appeared spontaneously while I’ve been reading Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials by Michael A.G. Michaud. This book wasn’t anything special, but it made me think what if an alien kid would one day reply to our random messages to the stars. And WHAM! You have Falaha.

With Falaha books now out of the way, what are your current and future writing plans? Are you going to base more stories in the same Universe?

Falaha’s life story is not really over. Falaha’s Journey opens to a bigger trouble/adventure in the end, which could take a novel or ten. I’m not going to write those yet. I’m going to work full time on the Rjg novel, set in the same Universe much earlier in time and related to Falaha’s story. Maybe I will write something else entirely in between its chapters, after I’m done with Falaha’s book 3.5, a collection of short erotic romance specials (I want to finish the third and possibly final story for it this year.)

I have noticed that you pay a great attention to the setting in your stories, which is very important for science fiction. What are, in your opinion, major basic components of world building?

I can’t speak for all worldbuilders out there, but personally I’m fascinated with creating fictional [planetary] systems from scratch and then imagine how life would evolve there, how the biomes would look like, and so on. My novel Rjg will feature all of these things and it’s quite a challenge. I use numeric models for my creations. While technical part (models and code) is easy for me, I have a lot to learn about the sciences behind these models, so there’s plenty of paper reading and studying. Space and earth sciences, biology, all fascinating. These are basic components in my worldbuilding, of course. I’m less interested in artificial space habitats beyond what I’ve created so far in my fiction, though. But that’s probably because I don’t have humans in these stories and I haven’t been dealing with ‘classic’ engineering concepts beyond basic reading on the topic. I’ll get to those someday.

Why did you choose to self-publish? What is the most rewarding part of being an independently published writer for you?

The only rewarding thing in self-publishing for me so far is that I have no deadlines. I work in relaxed manner that is physically sparing. The other reward is that no publisher would put a pseudohuman on my book cover. In all seriousness, I don’t want to be trad published (even with small press) for sole reason of obligatory things I will have to do. Contracts are binding and that is not want I see myself doing. International contracts are even more troublesome for me.

I know you design your own covers, which requires both skills and good taste. What are, in your opinion, important criteria for a good book cover to interest readers?

I can’s say my covers are perfect, but I like them. People like them, so I’m doing something right. They are not the best of the indie world, yet it is what I can currently afford. I had some experience in design and illustration, so I use whatever skills I have. Though sometimes it takes toll on my health. I have to work in moderation, or I’ll be spending a week in pain after a day of enthusiastic artistry.

If I could name one thing that makes a good book cover, that would be well-crafted symbiosis between a professional illustration and font(s) used. These are the covers that make you look at them savoring the richness of the world the illustrator presented and enjoying the simple yet effective use of typography. Like a good wine, that’s a winner. Of course, readers should read what the blurb says and see what’s inside the book. While mediocre cover can be forgiven if the story is great, no one likes deceptively alluring wrapping on a badly written book.

You compose music as well, how do you define your genre and what themes you explore in your compositions? Whose music has made an impact on you over the years?

I’ve listened to so much music that I can say all of it impacted me in one way or another. My preferences shift all the time. Today it’s death metal, tomorrow it’s opera, the day after it is new retro wave, ethnic beats, new age music… I usually write while listening to the music. There’s much inspiration to draw from sound. My own music doesn’t have a definite genre besides being story scores. My latest musical WIP is tied to my novel in progress. In that score I’m trying to imagine ethnic (folk) music of an alien culture, of course. I’ve made only two tracks so far, because I don’t have computing resources to produce more for now. I will return to music-making after I have a better machine.

Apart from writing and composing, you beta-read and review other people’s work. What stories grab your attention and what genres you’d never consider to read?

To be clear, I don’t review books – I can write a review on Goodreads or my blog if I want to do it. I don’t do reviews per requests. I do some beta-reading, however. I don’t shun genres as a whole, I prefer to pick stories according the description. Maybe said work is something that would interest me in a genre I would otherwise avoid. What grabs me depends on my mood, but I will read whatever I promised to read (my standard turnaround is 2 weeks.) Also, I don’t have issues with having all ages represented in fiction as well-rounded characters, yet I can honestly say that everything labeled YA or NA I would discard even without looking.

And finally, tell us about your presence online, where can readers find your blog, your stories, music and artwork.

I write under the pen name, Jeno Marz. Readers can find my blog/website visiting jenomarz.com. I have all my stories and links where to find them listed in the books section on my website. My stories are available in stores like Amazon, Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, and so on.

I also have the music section on my website and a profile on Looperman with a couple more tracks available.

The very first track I’ve written was The Morning Song.

As for my artwork, I have it either on my book covers, or what little I have created in the past years and put to use in my store.

About Jeno

Jeno Marz is a writer from Latvia, EU, with background in electronics engineering and computer science. She writes science fiction incorporating military, high-tech, science, horror, romance, and family relationships themes. All her fiction is aimed at an adult audience. Jeno also discusses fiction world building on her blog.

Jeno Marz is a writer from Latvia, EU, with background in electronics engineering and computer science. She writes science fiction incorporating military, high-tech, science, horror, romance, and family relationships themes. All her fiction is aimed at an adult audience. Jeno also discusses fiction world building on her blog.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JenoMarzWriter

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JenoMarz

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/JenoMarz

Blog/website: http://jenomarz.com/

Amazon.com profile: http://www.amazon.com/author/jenomarz

Smashwords profile: http://www.smashwords.com/profile/view/JenoMarz

September 23, 2014

Pelevin’s Russia: Buddhism, Schizophrenia, Politics, History and Postmodernism

Eighteen years after its publication, the novel Buddha’s Little Finger (Чапаев и Пустота) written by Victor Pelevin remains important and fresh.

[image error]

Graffiti in Kharkiv (Ukraine), illustrating Pelevin’s novel Buddha’s Little Finger by V. Vizu (own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...) undefined GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)]

There is a reason why Russia is such a mysterious country for the rest of the world. The never-ending chain of historical cataclysms moulded the country into the symbolic barrel with gunpowder that can explode any moment.Russians are used to abrupt changes in their life and that’s why there’s fatalism in our mentality and a lot of patience. People value periods of quiet life and are very reluctant to rebel and fight for changes. Yet, we like doing things very fast, in haste, to cut corners, to achieve our goals quickly – because life is short and may not give you a second chance.

At the same time, Russians are skilful at deception and double play, everyone distrusts the government or their neighbour. In paradox to that, Russian people are very naive, many buy into fairy-tales the Kremlin feeds them via media. Eastern Orthodox christianity is in a wild mix with paganism and superstition here. Pseudoscience and mystical doctrines are thriving in Russia.

Individuality is only valued in Russia when it goes together with wealth and power. It’s a land where social Darwinism is reality. Many of us are aggressive and blunt, yet, at the same time, everyone has heard of Russian hospitality and generosity. Russian tourists often spend fortunes abroad, they like showing their money, they burn bright and live now, because they know they can lose everything in a moment.

Russians seem to live in two parallel realities. They grumble about expensive life, decay of the country’s infrastructure, corrupt government and Western conspiracies that plan to destroy their Motherland, yet, at the same time, we believe that Russia is a God-chosen country, the world centre of spiritual Renaissance, where the smartest, kindest and most beautiful people live.

I believe the best way to grasp the mentality of modern Russian people is to read Russian books, especially the ones written by Victor Pelevin who is number one Russian author who explores Russian history, politics and society in his post-modernist works.

Buddha’s Little Finger is Pelevin’s most celebrated novel, a manifest of Russian Buddhism, I’d even say Zen-Buddhism. By saying zen I mean that Pelevin’s heroes are already enlightened, but either forgotten about it or on their way to realise their enlightenment. Zen or not Zen, in the country with the communist past where atheism was norm, the Buddhist worldview is an alternative for those who couldn’t convert back to traditional Christianity.

Petr Pustota (Peter the Void) is the main protagonist in Buddha’s Little Finger. We meet him in an enlightened state: he’s at the madhouse receiving treatment for his mental illness. His other personality believes that he lives during the times of Civil War in Russia, in 1919, where he’s been spiritually guided by the Red Army commander, Vasily Chapaev, and fallen in love with a beautiful machine gun operator and Chapaev’s deputy, Anka.

Petr’s new treatment is designed as a collective hallucination between him and his inmates at the asylum. He learns about Simply Maria, a guy whose other personality is a girl from a Mexican soap opera, and her adventure with a Terminator, a bizarre story symbolising an “alchemical” marriage between Russia and the West. Stories of other inmates are equally depressing, especially if we interpret them as scenarios of Russia’s future fate.

Petr’s doctor claims his patient’s mind healed. When Anka wipes out all existence with her clay machine guy – Petr grasps the idea of Void. We all exist in this Void and are made of it, and we don’t know why, since we can’t know something that is the Void, Nothingness. This is me interpreting, however imprecisely, Petr’s realisation of his enlightenment.

This novel is a mental exercise, a clever way to pull readers out of the tight clasp of material culture, to make us think big questions. It is also a clever political satire on contemporary Russian history and the way Russian history repeats itself: the wild times of Civil War are likened to post-communism era of 1990s. And since it repeats itself, we may as well take it philosophically. No borders between dreams and reality, sanity and madness, past and present, there is only the Void.

September 17, 2014

Moscow International Book Fair – Winds of Change

In addition to the Congress of Translators, I was fortunate to attend the 27th International Moscow Book Fair on the 3-7th of September 2014. There I participated in a panel discussing self-publishing revolution and its onset in Russia.

Russian book industry is lagging behind its American counterpart in terms of its infrastructure and general consumer’s habits, yet its gross value is impressive – over 2 billion dollars a year. Most books in Russia are sold in print (97.5%) with an average price of five dollars, ten dollars in Moscow, while ebooks – 2.5% of the book market share, with a price of three dollars per ebook on average (the source is bookind.ru).

Who would resist seizing a throne like that? I couldn’t

The book fair had attracted over a thousand of book industry experts and publishers from sixty three countries. Over 200,000 book titles were presented at the fair. Over 220,000 visitors had a chance to meet famous authors from Russia, UK, France, Poland and other countries.

As for my participation, I have shared my experience of selfpublishing in the UK with my Russian colleagues. Self-publishing has a long history in Russia, sites like Proza.ru and Lib.ru have been accumulating millions of selfpublished ebooks over the years that can be accessed by readers for free.

Children literature is one of the biggest segments of Russian book market

Monetising selfpublished works is a big problem in Russia. The vast majority of legacy published ebooks are pirated. Not that many Russian people are willing to pay for ebooks, especially if the books haven’t been properly written, edited and formatted as is the case with many self-published titles. Yet, it’s all changing now with anti-piracy laws becoming stricter.

Sites like Bookmate, Samolit and XinXii now distribute free and paid books written by self-published authors. The biggest ebook retailer Litres.ru also accepts such titles, as rumour has it, on an individual basis. Monetisation is now a very popular word in Russia.

Russian scifi author of ‘Night Watch’ pentalogy Sergei Lukyanenko is speaking at the 27th Moscow International Book Fair

Our panel hosted by Knigabyte focused on first successes of self-published authors in Russia. I have talked about ways of how Russian indie authors can break out in the oversaturated Western book market and I pointed out that one has to be extremely resourceful and competitive to achieve commercial success in the West.

I think that many Russian authors can at least succesfully fit the same niche as Bulgakov and Solzhenitsyn dealing with Russia’s international image, if they focus on historical and political aspects of their works. Russian authors and publishers should be more pro-active outside Russia in terms of connecting to non-Russian audiences.

If you want to be read widely, communicating your writing is as important as writing itself.

September 12, 2014

Books vs War: Russian Literature as a bridge between cultures

The Winners of 2014 ReadRussia Translation Prize (photo credit: Russian Institute of Translation)

War tears nations apart and it takes more than long negotiations and ultimate truce to mend broken peace, – magic glue, perhaps. Literature like any other form of art can be this mending glue. Literature unites people of different nations, faith and age, provides insight into history, psychology, sociology, cultural and family values of a given nation. And it is the translator who interprets words of one culture to another. The cultural peacemaker.

I had been invited to attend the III International Congress of Translators of Russian Literature, which took place in Moscow last week (4-7 September 2014). It was such a delight to meet translators from fifty five countries who gathered to speak about their work at the Foreign Literature Library, in Moscow. The congress was organised by the Russian Institute of Translation, an organisation that provides grants to publishers who wish to publish classical and modern Russian books in translation.

The finale of the congress was a ceremony featuring an announcement of 2014 ReadRussia Translation Prize, which took place at Pashkov House overlooking the Kremlin.

Pashkov House in Moscow

The prize featured four categories.

contemporary fiction written after 1990. The Winner – Marian Schwarz (USA) and her English translation of L. Yuzefovich’s Harlequin’s Costume .

20th-century fiction written between 1900 and 1990. The Winner – Alexander Nitzberg (Austria) and his German translation of M. Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita

19th-century fiction written between 1800 and 1900. The Winner – Alejandro Ariel Gonzalez (Argentina) for his Spanish translation of F. Dostoevsky’s The Double

poetry (classic and contemporary). The Winner – Liu Wenfei and his Chinese translation of Alexander Pushkin’s poems.

At the congress I had presented a talk on promotion of modern Russian literature outside Russia. Why are new Russian authors not so well known as Russian masters? It’s all simple – in our world that is over-saturated with information one has to promote one’s art. So, amongst others I had suggested putting some effort into the following areas:

discoverability (making sure the information on Russian books contains right metadata and it is search-engine optimised)

promotion (via social media and book recommendation websites)

book giveaways (to attract new readers and reviewers)

contacting bloggers and Russian expats who love reading (word-of-mouth is best promotion)

educational efforts (book festivals, literary events at schools, libraries, meetups and online conferences with Russian authors,etc.)

Over the last couple of years I have been promoting Russian literature via my blog. I have received so many emails from you about new Russian reads, so I am happy that this hobby of mine is useful.

If you are looking for other sources about Russian books, here are useful links:

Glagoslav Publications (specialises in Slavic literature)

Glas (new Russian books)

Russian Literature Online

Read Russia

Lizok’s Bookshelf (translator Lisa Hayden on modern Russian reads)

Meanwhile, I’ll keep introducing you to Russian literature. My WIP is a systematic guide/catalogue of new Russian books. Watch this space.

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzghulDiUtk