Grigory Ryzhakov's Blog, page 2

May 22, 2015

Zwinger: The Art Thriller. Interview with Elena Kostioukovitch

Elena Kostioukovitch (photo by Alex Pivovarov)

Today I’m having a conversation with Elena Kostioukovich, a literary agent, visiting professor at several Italian universities, author and translator of Umberto Eco novels to Russian.

***

Elena, first of all, congratulations on the Italian translation of your novel Zwinger, which is titled Sette Notti (Seven Nights) in Italian. I hope the English translation will follow shortly. Publishers, do take note and don’t miss out on this new ‘Da Vinci Code on steroids’. You may start stalking Elena for the English synopsis here.

Jokes aside, my first question is why Zwinger? Elena, you have a prominent profile in the international literary establishment, and becoming an author and writing an novel that deals with Holocaust, KGB and other disturbing memes, is quite daring. And you expose your family history there too. So what is the story in a nutshell and what made you write and publish it?

The Russian edition of Zwinger (book cover)

I’ve been thinking of turning my family history into a narrative for a long time. I consider this a curious game, the game I love, a way of communication with the reader. In my opinion, the best kind of writing is creating texts with elements of fiction yet containing references to the real events.

You may ask me why I decided to write a novel but not a biography or a chronicle if facts are so dear to me. The answer is simple: there are always gaps between the facts. And those are nothing to fill up with, apart from fiction. For that reason, any biographies feature made-up things, versions, opinions, hypotheses, i.e. fiction.

So I thought it’d be honest to call all this a narrative, and fill the gaps with details and connections, so dear to our hearts, made-up details.

Why have I chosen to base it on the family history? Only from this factual material I can mold though fictitious yet quite accurate details and links. I know everything intimately in this history, from the inside. So I don’t make things up randomly.

That’s exactly the main story line of the novel: the old hasn’t died, it still lives inside the new, like our ancestors live inside us, and something they couldn’t tell we can shout out. It’s important to think it through, to invest yourself into and live in this old experience.

Sometimes, when you are tired you can get into complex parts of your consciousness. When you are tired, the brakes of shame and fear are gone. The main protagonist of Zwinger, Victor Zieman, my alter ego, gets mentally overloaded during the book fair, gets so tired that his mind makes him see things: suddenly he finds a solution for some mysterious questions, he was at lost with when he was sober.

In parallel with Victor, my reader gets overwhelmed too. I create a flood of information, similar to what Victor gets, that crushes his nervous system.

In Zwinger, the main protagonist, Victor, finds himself unravelling mysteries. You have been translating Umberto Eco. What impact did Eco’s writing have on you, your writing style, voice and narrative?

I think you are right about this; my novel is narrated by one of the regular Eco’s characters – an intellectual, left-wing, dreamer burdened with psychological complexes. Such characters narrate their stories, from the first persons point of view, in Foucault’s Pendulum (Casaubon), The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (Bodoni) and Eco’s latest novel, Number Zero (Colonna). I don’t know if many readers noticed but his characters’ last names represent the names of (Word) fonts, which underlines the artificial, fictitious nature of Eco’s narrators.

This type of character in Russian I needed to arm with special language, which I molded out of my own reading, student jokes, even my family folklore. Out of the humor. I constructed this language for my Eco translations for thirty years.

But, as it turned out, this language has taken over me. When it came to a decision of how my character will be conversing – a troubled intellectual – I realized that the language I bestowed upon Eco’s characters is the most natural and the only possible one. So, I opened the tap and the language flowed.

Zwinger features many flashbacks, one of them is the funeral of Vladimir Vysotsky, the beloved Russian bard, in Moscow during the Olympics in 1980. Was this written based on your personal memory and what role does this subplot play in the novel?

Of course, Vysotsky’s funeral, Moscow Olympics, fake Pravda, teaching students on Russian course in Milan, Frankfurt book fairs, the Babi Yar commemoration events and so on – these are all my personal memories of things I felt and lived through.

As what one might expect from a translator of your caliber, you operate with a massive vocabulary in Zwinger: the novel contains many references to history, art and the world of publishing – what I call ‘the elitist bits’. I think these ‘bits’ are important as they show the author has researched the subject well, and also they add authenticity to the novel. How do you decide on the balance between the story plot, the characters and these ‘elitist bits’, the balance between a story and an essay?

I needed to re-start the readers’ memory, to overwhelm them to the same extent as my protagonist is tortured by erudition, new information and troubling memory.

Half-mad from all the haste, disease, lack of sleep and skipped meals, Victor enters a state of trance, his intuition takes over the reins, and he finds answers for mysterious questions, which his normal state was unable to solve.

Elena Kostioukovitch (photo by Alex Pivovarov)

Akin to Zwinger, your own life is a roller-coaster that landed you in Italy. How did this happened, Elena? Why did you swap Russian winters for Mediterranean splendours?

Your question is on point here. I’m not very fond of cold Moscow winters. I was born in Kiev, winters are warmer there. So, during my Moscow years the cold had been an issue for me. And frankly speaking I have never loved anything, even Russian literature, even any of my admirers, as much as I love Italy: I have fallen with her from the first sight.

Remember, Gogol once wrote about Italy, ‘Russia, snow, rascals, the department – I must have dreamt of them in my sleep and then I woke up in my Motherland.’

There was a technical issue: How to make Italy love me in return? So we gave each other something. And there it was. Italy gave me my children, its vast lands, lines and colours, scents and sounds. I gave her my work. I wrote a book on Italian food, now I am writing another on sculpture, architecture; with God’s help, I’ll finish it in three years or so.

Do you think the differences between Russian and Italian mentalities find their reflections in the national cuisines? What makes a dumpling Italian, Ravioli, or Russian, pelmeni?

Do you think the differences between Russian and Italian mentalities find their reflections in the national cuisines? What makes a dumpling Italian, Ravioli, or Russian, pelmeni?

Ravioli is an Italian dish mainly because it belongs to the Italian enormous culinary symphony, in which this dish is one of the instruments in the orchestra, colors of the palette.

‘Raviolo’, a speciality in Marche, is called ‘agnolotto’ in Piedmont, ‘anolino’ in Parma, ‘marubino’ in Cremona, ‘tortello’ in Emilia, ‘pansoto’ in Liguria, ‘tordello’ in Toscana, ‘cappellaccio’ in Ferrara; and in each region they use a distinct sauce and spice for ravioli, as well as specific shape and color of the plate. And Italians appreciate and like the fact that in the neighbor region the same food is called a different name. The same concern paintings: even an Italian person not specialised in the art easily discriminates between Siena and Toscana styles, and those from the Venetian, and the Ferrara style from the rest. And, while in the museum, he enjoys the way paintings by different schools are exhibited side by side.

Considering your impressive work in the past, you have, no doubt, tremendous future plans as a writer and a translator. What can we expect from you next?

Of course, I have been thinking about a grand project. I don’t know whether or not I’ll have strength and time for it. It is a huge work, a kind of travelogue on different regions and topics: sculpture, architecture, iconology. I want to do this, so the travelers who read the book could see each and every town in Italy in their bright distinct light.

—————————————————————-

You may contact Elena at http://www.elkost.it/

Here is the book trailer for the Italian edition of Sette Notti (Seven Nights) historical quest novel by Elena Kostioukovitch

May 18, 2015

My Book Adventures: Spring 2015

London Book Fair 2015, Olympia Exhibition Centre

Some of you might have noticed that I’ve taken a break from blogging, yet I wasn’t seeping port and watching talent shows while lying on a hammock under a leafy palm. In April, aside from scientific adventures, I’ve published a new book, attended London Book Fair, then the Russian Prize awards ceremony in Moscow, flew across eight time zones in Russia back and forth, and translated my debut novel, Mr Right and Wrong, into Russian.

Moi at Slovo 6 (photo: Evgeniya Basyrova)

I’ll start with the 6th Russian Literature Festival Slovo, which included talks and workshops by Russian celebrity authors at the Waterstones flagship bookstore in Piccadilly, London. The retro-crime fiction star, Boris Akunin, opened the festival by discussing the profession of writer with a fellow author Jeremy Noble. Akunin mentioned that apart from writing his stories for sheer entertainment he’s interested in exploring the phenomenon of villain. Every book of his features a unique kind of villain, and he’s particularly pleased when the reader is confused whom to root for: the protagonist or his archenemy.

Boris Akunin’s new book, The Planet Water

I mention Akunin specifically, since he has just released a new fabulous collection of three novellas called The Planet Water, another book in the series about the private sleuth Erast Fandorin, that will be without doubt translated into many languages, and which I have just finished reading. Fandorin’s character is now pretty mature and rounded, but the fate still throws stones at him challenging his worldview. Here we have exotic locations: Caribbean, Canary Islands, Central Europe and Ural Mountains; political intrigue (Anglo-German pre-WWI tensions, the rise of Bolshevism) and, as always, effortlessly readable, yet inventive prose. Akunin does extensive research before writing his retro-detective books, yet he said that he doesn’t read fiction anymore, he’s afraid of being stylistically influenced by other authors. I would argue that reading fiction in a foreign language shouldn’t affect his writing in Russian.

Moving on to London Book Fair, it was a third one in a row I attended. This year it had changed location and was hosted at London Olympia exhibition centre. Most of the time I spent at Author HQ lounge to get the feeling of the publishing industry zeitgeist. The ebook and self-publishing tsunami has passed, the competition is fiercer than ever, and no quick tips to stardom were revealed. It’s all about being the best you can in everything: writing, packaging, and marketing. One common idea was reappearing in talks: authenticity and uniqueness.

Conchita Wurst on being truly who you are

As a writer you need to stand out from the crowd, yet to do so genuinely. The audience has acute sense for authenticity. In the non-fiction section presenting her new biography in English, a bearded lady Conchita Wurst, the last year’s Eurovision winner, was talking exactly about that. No matter how controversial her act was, she was sticking to it fearlessly: the act wasn’t a gimmick to attract media coverage but an alter ego of Thomas Neuwirth, a person behind her. The lad grew up listening to Shirley Bassey songs and wanted, like his idol, to sing and perform, and in the end he did follow his dream. A beard on a drag queen is not exactly a novelty. But it worked in this case, because the beard was a symbol of Conchita’s proud-to-be-different persona. So, a tip to note: make sure your quirky bits are an integral part of your brand not just a gimmick.

The same can be applied to writing. It is about our voice being unique and coming from the heart, not about following trends while pursuing wealth and celebrity status. With millions of authors around, being you is the only viable option.

Now about the technology. LBF2015 once again tackled the problem of standing out from the crowd. New marketing strategies have emerged. And they are all about trying out something new. A proven strategy gets old and inefficient when overused. The on-going novelty is the key.

An author called Karen Healey Wallace presented her self-published book, The Perfect Capital, that won several design awards and sold a thousand of copies, which, considering $20 price tag for a print copy, is a huge achievement. She approached the problem of ‘how to stand out on a bookshelf at a bookstore’. The overall galley-copy look and smart typography makes her book an eye-catcher. It could have been yet another generic looking self-published literary fiction novel that no bookstore wants. Publishing books is like dating: you want to look your best and wow potential partner on the first date. Only then, you’ll get the chance to reveal your rich inner world later on.

An author called Karen Healey Wallace presented her self-published book, The Perfect Capital, that won several design awards and sold a thousand of copies, which, considering $20 price tag for a print copy, is a huge achievement. She approached the problem of ‘how to stand out on a bookshelf at a bookstore’. The overall galley-copy look and smart typography makes her book an eye-catcher. It could have been yet another generic looking self-published literary fiction novel that no bookstore wants. Publishing books is like dating: you want to look your best and wow potential partner on the first date. Only then, you’ll get the chance to reveal your rich inner world later on.

I find it useful to interact with professionals outside my field: it broadens your perspective. For that reason, I’ve attended Julia Harvey’s talk on ‘marketing tips for tech start-ups’. A lot of that applies to self-publishing, as it’s a form of start-up. Lessons I learned, which were beautifully illustrated with some real life business cases, can be summarised in bullet points:

Be passionate about what you do because your passion translates to your customers

Do the tweaking, keep testing things, constantly learn what works and what doesn’t, because in this overcrowded industry nimble authors, who are not afraid to experiment, win.

Following that, use analytics tools such as Google Analytics, to see what’s working and what’s not. Collect as much data as you can, you will be surprised how useful it may turn out later on.

Interact with people, build networks. Writing may be a solitary thing, but self-publishing doesn’t have to be. By networking you’re spreading the word about your brand and creating for yourself more opportunities.

You may contact Julia at @marketingjulia or #7startupsecrets.

One of the things I am interested in as an author is reaching international audiences. I have a book translated into Chinese and published in China last Christmas. So, I attended a talk about engaging the Chinese reading audience (more readers than US and Europe put together), and the information it contained could be applied to audiences speaking other languages.

If you have your author website, it’s also good to have:

Key message in multiple languages

Meta-data optimised for Chinese visitors (or other audiences)

Small tools for foreign visitors

Localisation integrated automatically, for instance, redirection to country-specific Amazon book pages

Local partners who will help to spread the word about your book (product).

So, LBF ended but left plenty of food for my thought.

Those of you who are passionate about the news of Russian literature, will be interested to know that after LBF I flew to Moscow where I’ve attended an award ceremony of Russian Prize (Русская Премия), annually celebrating works of the authors living outside Russia but writing in Russian.

Russian Prize (Русская премия) 2015

The award is organised by the Yeltsin Centre with participation of Naina Yeltsin, the Russian ex-first lady. The winners were:

BEST POETRY – Jan Kaplinsky (Estonia) for Белые Бабочки Ночи

BEST SHORT PROSE – Yuri Serebryansky (Poland) for Пражаки

BEST NOVEL – Alexei Makushinsky (Germany) for Пароход в Аргентину

If you live outside Mother Russia, you can submit your own precious writing in Russian here to be considered for the next year’s awards.

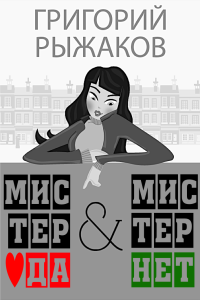

And finally, ta-dah, I reveal the teaser Russian cover of my debut novel, Mr Right & Mr Wrong. I’m now looking for a publisher in Russia, fingers crossed.

I hope your spring was no less eventful.

March 29, 2015

Literature as a medicine for our stagnation

Books on the power-line by Katja Ullrich (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

One may ask why reading as a past-time is still essential now.As a society, we don’t question the importance of reading as a tool of personal development, of building a view of the world and understanding of science, culture and ethics. But gradually reading is becoming just an educational tool for young people and it seems to be dispensable for the well-being of adults.

There is a concept of ’reading for pleasure’, which I particularly dislike. With the onset of digital revolution and the blossom of all forms of entertainment, reading seems to have lost its dominant role as a form of media. But how does it affect us?

An average person nowadays is constantly and increasingly bombarded with information, and after a hard day’s work all we need is to relax and watch a show that would entertain our old brain: anything to deal with food, sex or danger (violence/politics).

Most of the readership prefers lighter reads, romance or thrillers, and literary fiction is considered boring and only suitable for intellectuals. Our attention span is short: a three minute video on YouTube or a ten seconds read per post on Facebook or split second flips through Instagram shots (that sometimes last for hours) would do. We are flipping through our lives, often unable to stop and ponder over important things.

Are we losing the ability to process information in a thorough way outside our jobs? I think we do. We don’t like challenging reading, our brain resists it; we are trained to react quickly to small and easily digestible bits of information. This robs us of richness of the literary world, of the world itself.

Biggest minds of the mankind spent months and sometimes years to complete their pieces of work. And thanks to digital technologies, we can now instantly access this distilled thought of writers from many countries and nurture our own thinking process. We can evolve our minds and imagination, create bolder things, achieve more in life and bring up a better, smarter next generation.

I love meeting with readers and writers, with people who adore words, to whom books are often like friends. I spot voracious readers easily: their lexicon easily exceeds a thousand words, they are often erudites, so you never run out of conversation topics with them.

Another important aspect of reading is understanding other cultures. We often get stereotypical judgements from the news about various countries and mentalities. Reading books by foreign authors allows you to see the culture as it is, rather than receive one-sided and superficial projections as in TV reports.

And I’m happy that I myself contributed to bridging cultures with publishing my guide on modern Russian literature. Yes, it is finally out on Kindle and in print.

And I’m happy that I myself contributed to bridging cultures with publishing my guide on modern Russian literature. Yes, it is finally out on Kindle and in print.

Russia has a troubling image in the news, but the country is not defined by the Kremlin only, it stretches across 17 million square kilometers of land and comprises of hundreds of nations. I hope more readers will now discover modern Russian authors and learn about Russia from insiders and Russia’s greatest minds.

If you have read the guide already and found it useful, please recommend it to other readers and leave a review of it on Amazon or Goodreads. Spread the word about literature, Russian or any other.

Because, reading is fundamental.

February 26, 2015

A Genius Rediscovered: The Scientific Legacy of Sabina Spielrein

This year the world celebrates the 130th birth anniversary of Sabina Spielrein, one of the greatest minds of the XXth century. Sadly, she was forgotten and have only recently been rediscovered. We are only beginning to realise the impact of her ideas on modern science and on our understanding of human psychology. I am sure that the dramatic story of her life will inspire many people.

This year the world celebrates the 130th birth anniversary of Sabina Spielrein, one of the greatest minds of the XXth century. Sadly, she was forgotten and have only recently been rediscovered. We are only beginning to realise the impact of her ideas on modern science and on our understanding of human psychology. I am sure that the dramatic story of her life will inspire many people.

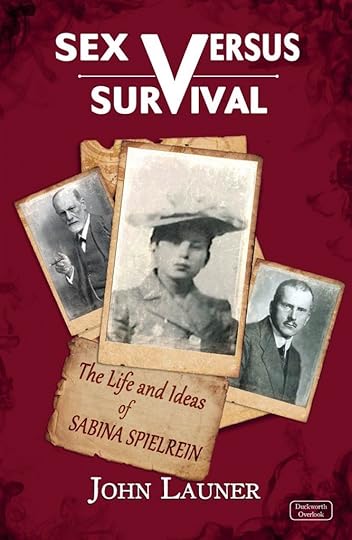

I am delighted to post here a guest article by John Launer, the author of the new Spielrein’s biography called Sex vs Survival.

—

Sabina Spielrein was a Russian-Jewish psychiatrist and paediatrician, best known for being a patient of the famous psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, and then one of his mistresses. An increasing number of people now recognise that she was also one of the most original thinkers in psychology in the twentieth century. She was born in Rostov-on-Don in 1885 but worked in Zurich, Vienna, Berlin, Geneva and Moscow, before returning to her home town for the last twenty years of her life. Because of anti-Russian prejudice in the west, anti-Semitism, and Stalin’s repression of intellectuals, her own writings have remained almost known until recently. She wrote in three languages and covered a vast range of topics from mothers-in-law to schizophrenia, evolution and the development of speech. After her tragic death in the Holocaust in 1942, she was completely forgotten both in the west and in Russia. Historians only began to rediscover her work in the 1980s and 1990s.

In her writing, Spielrein brought together psychoanalysis with the study of children’s development, biology and neuropsychology. She used ideas from both Jung and Freud, and tried to persuade the two men to make contact with each other after their bitter split. She worked with the great educational psychologist Jean Piaget and was his psycho analyst. Later on, she helped to run a famous psychoanalytic kindergarten in Moscow – after Stalin shut it down, he gave the building to Maxim Gorky and it is now the Gorky Museum. She taught the two eminent Russian neuropsychologists Alexander Luria and Lev Vygotsky. She influenced all these men and helped them to form their ideas. However, she was a modest individual and a bridge-builder, and she never tried to take credit for her influence or gather a following around her. As a result, the men around her often failed to acknowledge her importance.

The list of Spielrein’s intellectual achievements is extraordinary. When she was still a medical student, she wrote a dissertation about the importance of trying to understand the way that people with schizophrenia speak. At the time, almost everyone assumed it was ‘nonsense’, and she was one of the first to realise it had a special kind of sense and logic to it. A year later, in 1912 she wrote a paper called ‘Destruction as the Cause of Coming into Being’. She based it on Darwin’s idea of the preservation of species, making a link between the apprehension of death and the imperative to reproduce. The paper combines a huge range of learning from philosophy, literature, religion and anthropology as well as psychiatry. She drew on Nietzsche and also the symbolist writers Solyovov and Ivanov. She was also very familiar with the work of the great Russian scientists of her time including Ilya Mechnikov. Some of the ideas in her paper anticipate thinking from the field of evolutionary psychology in our own age.

Spielrein was almost certainly the first person to use psychotherapy with children, and to work with them through play rather than words. She understood the importance of the relationship between mothers and infants, long before other thinkers like Melanie Klein and Anna Freud wrote about this. Some of her papers have a feminist emphasis, and she understood the difficulties that women face in their choices about reproduction. She agreed with the Hungarian psychoanalyst Sandor Ferenczi that psychiatrists and therapists should develop warm and equal relationships with their patients, rather than claiming to work from a position of superior knowledge and objectivity. In the 1920s, she helped to develop Russian pedology. This was a science that tried to break down barriers between medical, psychological and educational ways of looking at children. The historian Alexander Etkind has written about the history of pedology and her contributions to it (1). A hundred years on, all these ideas and ways of working look very much ahead of their time. In many professional fields, people are only now beginning to rediscover the same ways of working.

How is Sabina Spielrein now regarded? Sad to say, most psychiatrists and psychologists have still never heard of her – or they know of her as the hysterical patient and passionate mistress played by the actress Keira Knightley David Cronenberg’s move: ‘A Dangerous Method.’ Many people use the same ideas she came up with, without realising she was writing about them a hundred years ago. There was no accurate biography of her until a few years ago when Sabine Richebaecher wrote one in German: it in now available into Russian (2). My own recent biography is the first book to cover the development of her ideas and to summarise most of her papers (3). A number of scholars in the United States and elsewhere are beginning to write about the importance of her ideas, particularly about the relationship between mothers and their children, and the way this develops through the use of sounds and then language.

Russian thinkers have often been ignored or forgotten in western universities and in history books. In accounts of psychology in the future, Sabina Spielrein deserves a very important place. I believe that people will come to recognise her importance in twentieth century intellectual history.

Etkind, A. (1997) Eros of the impossible: The history of psychoanalysis in Russia. Boulder CO: Westview Press. [In Russian:Эткинд А.М. Эрос невозможного : История психоанализа в России. – СПб. : Изд. дом “Медуза”, 1993. – 463 с. ; 21 см.]

Richebächer, S. (2008) Eine fast grausame Liebe zur Wissenschaft. Munich: BTB. [in Russian:Рихебехер С. Сабина Шпильрейн: “почти жестокая любовь к науке” : биография /Сабина Рихебехер; [пер. с нем.: К.А. Петросян, И.Е. Попов науч. ред. и лит. обраб. пер., вступ. ст. и примеч. в тексте – к.психол.н., доц. Ф.Р. Филатов]. – Ростов-на-Дону : Феникс, 2007. – 413 с., [8] л. ил., портр., факс. ; 21 см.]

Launer, J. (2015) Sex versus survival: The life and ideas of Sabina Spielrein. New York, NY: Overlook Press.

—-

January 22, 2015

Russian Life on Russian Life

Russia may be a mysterious country, yet some people have been very proactive at popularizing Russian culture in the West. Today, I am pleased to host an interview with Paul Richardson, an editor of the popular Russian Life magazine.

Russia may be a mysterious country, yet some people have been very proactive at popularizing Russian culture in the West. Today, I am pleased to host an interview with Paul Richardson, an editor of the popular Russian Life magazine.

Russian Life has been informing its audience about the vastest country in the world, Russia, for over half a century now. Since your magazine was born in the Cold War Era, what’s the story behind it? Who was the primary audience back then?

Paul: Well, we actually only acquired Russian Life in 1995, after it had lived out almost 40 years of its history as USSR and Soviet Life. Before us, it was a propaganda instrument of the Soviet government, albeit a relatively watered-down one. We made it a privately run magazine with no ties to any government or media corporation. And we strive to have a broad range of American, European, and Russian contributors, so that it presents a well-rounded, reasonably balanced view on a country that is often rather controversial and mysterious.

The readers if Soviet Life and Russian Life have always been an interesting and rather unusual breed of folk, and, due to the history of the magazine, they are mostly Americans. I say unusual, because as a general rule, most people are more interested in and concerned with local issues, with the history of their own country or locality. But for many people, there is something irresistibly intriguing about Russia (because they have traveled there, studied the language, fell in love with the literature, married a Russian, adopted a Russian, been affected by world events, etc.), and so that is whom we serve…

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has undergone dramatic changes, how did the focus of the magazine change?

I have not analyzed the magazine’s focus pre-1991, but as I noted, the purpose of Soviet Life back then was like Russia Today is for Russia now, as a tool of “soft power” – to spread the government’s interpretation of events to the wider world.

We of course have nothing to do with “soft power.” Ours is an independent journalistic enterprise, and we haven’t changed our focus since taking on the magazine in 1995. Our goal has always been to provide an insightful, informed, balanced view of all things Russian, to tell interesting stories and to provide readers with enough information that they can form their own, independent view of Russia, without the filters of governments and big media companies.

As a wonderfully unique ad-on, Russian Life also regularly publishes a journal of Russian literature in English called Chtenia (Readings), featuring newly translated works of Russian authors. As we both know, Russia has many readers and probably even more writers, only joking. How do you decide on what stories to translate and publish?

Yes, Chtenia is in its eighth year now and it has been quite a departure from Russian Life. We started it because we were helping put together Life Stories – a collection of short stories to raise money for Russian hospice. Through that we met many great writers, translators and agents, and realized just how little Russian literature was getting through. So we decided to take this idea to the readers of Russian Life and see if it was a publication they would support, and we were pleasantly surprised.

What to publish is always a challenge, because there is a sea of material out there and we can only offer a small rowboat. So we decided from the beginning that we would build into the publication a filter of sorts, by making each issue have a theme. That focuses our efforts and helps us find relevant material, from fiction and nonfiction to poems and photography. But of course then it is all about choosing interesting themes!

In the last two years we have moved to a system where each issue has a Curator who helps form the issue along with the editor. We did this as a way to bring in more fresh ideas for content and material. It is creating some amazing issues.

How can one subscribe to/purchase your magazine? What countries is it available for delivery?

Both Russian Life and Chtenia can be subscribed to via russianlife.com (or, more specifically, store.russianlife.com). We have subscribers in over 50 countries and will ship to anywhere in the world that is serviced by mail. Russian Life is also available as a digital publication via Apple iTunes, Amazon and Magzter. All our books can also be purchased via our website.

Everybody has influences that shape our path in life. So what made you choose the path that led you to Russian Life? Any particular books, authors, films?

Personally, I was a child of the Cold War (literally born days before the Cuban Missile Crisis broke out) and developed a fascination for all things Russian in college, after a trip to Moscow and St. Petersburg in 1981. I went on to study it in graduate school, then worked in Moscow for a time before setting up our publishing company 25 years ago this March.

In Russia, about a half of all published books are foreign titles, in the US – maybe a few percent, and those few are completely dominated by Coelho, Murakami and Scandinavian thrillers. Do you believe there are ways to make Russian books, especially those by modern authors, more attractive to American?

Yes, I understand it is about 3 percent in the US. I don’t know if there is a purposeful way to make Russian literature “take off.” Who would have thought that Scandinavian literature would be so big before the Dragon Tattoo series? Something just has to happen. That said, Russian literature has always, I feel, had a rather strong reputation and strong presence in the US market, ever since Constance Garnett began translating Turgenev and Tolstoy and Chekhov.

Think about it: how many Chinese authors can your average informed American name? Yet most can name the three above, plus Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, Bulgakov and many others. That they are not best sellers is another matter. But then I understand Petrushevskaya’s stories do very well on the best seller lists…

As with anything, making modern Russian authors attractive to Americans is partly about marketing, partly about being in the right (completely unpredictable) place at the right time with the right book, and partly about events. Russia is not the most popular of countries in the US right now (except perhaps as a source for TV and movie villains), so that certainly is a factor that makes things harder…

Do you see any successors of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in the modern Russian literary world?

As you noted above, there are many many more writers today than there were 100 years ago. And they are far more specialized, I think.

The great thing about Chtenia is that it constantly is introducing us to new writers. It’s also a great way to find someone who you never heard of before (but whom Russians may be well aware of), to be amazed by their skill and perception. For instance, our most recent issue of Chtenia is almost entirely comprised of memoirs, memoirs of literary personages living through very difficult years in the Soviet Union. I was blown away to read the work of Izrail Metter and Olga Bergholz, for instance.

There are so many Russian writers worthy of wider attention, but for each reader the list is going to be very different. I think you need to go in search of Russian writers that write in the genre you are most interested in and see what they have to offer.

And finally, I would like to ask about future plans of Russian Life. What is in store for your readers?

Well, as always, we have many interesting stories in the works. And I am continually amazed how events move in mysterious ways. For instance, we have long been planning to have a few stories on Murmansk, in the Russian North, in our coming March/April issue, and then the Russian movie Leviathan, which takes place in that very region, won the Golden Globe for best foreign film, and there is talk it has a chance at the Oscar. Meanwhile, it is not totally beloved in Russia (where it has yet to be officially released).

Publishing on Russia is always interesting…

P.S. If you are interested to learn about Russian Life’s next exciting project, Red Star Tales, a collection of Soviet and Russian Science Fiction, please visit its Kickstarter page here.

Only a few days left to support the project.

January 1, 2015

A Rediscovered Life of Sabina Spielrein: Sex vs Survival

Sometimes, history corrects itself, and we re-discover a forgotten gem or a genius. In the latter case, it is a matter of historical justice to finally acknowledge a contribution of such a genius to the progress of our civilization.

It is a great pleasure for me to introduce you to one of the most original thinkers of the XXth century, an almost forgotten Russian psychologist Sabina Spielrein, whose recently published first full biography in English called Sex vs Survival I review in this blog. The book is written by John Launer, an honorary lifetime consultant at the Tavistock Clinic in London, a UK leading institution for psychological treatment. He’s also an Associate Dean for postgraduate medical education at the University of London.

John Launer, source: Duckworth Overlook

The book was is written in a chronological manner and based on a great number of documents, including publications and letters of Spielrein, Jung and Freud. The amount of work done by the author is truly colossal here. I was captivated all the way through. And though I am no psychologist, I’ll try to tell you what I’ve learned from it.

The book begins with young Sabina ending up in Burghölzli Hospital near Zurich diagnosed with hysteria that was arguably triggered by the unhealthy emotional atmosphere in her family and the death of her sister, Emilia. There she’d been treated and ‘psycho-analysed’ by Carl Jung himself. This was a start of their turbulent relationship, a topic that occupies a major part of this book. Launer argues that love and not what Jung called ‘psychoanalysis’ cured Sabina from obsessive torments. After her recovery, Sabina enters a medical school in Zurich, but her troubled affair with Jung will keep her unstable for years to come.

The problem here is that her love to Jung seems to be more platonic than sexual, while in Jung’s case I’m not even sure there’s a love, considering his track record as a womanizer.

I have previously blogged on A Dangerous Method, a Hollywood film loosely based on the similarly titled John Kerr’s book. Armed with documented evidence, Launer criticizes Kerr for some of his groundless assumptions about the Spielrein-Jung relationship. Launer also describes a conspiracy between Freud and Jung against Spielrein: Jung claimed Spielrein was his patient when it suited him and created a web of lies, while Freud tried saving the reputation of psychoanalysis by pacifying Spielrein. Only years after, Freud found the truth and since then highly regarded Spielrein as a colleague.

Launer goes on to dissect Spielrein’s scientific work. Working at Burgölzli as a student clinician, Spielrein pioneers in schizophrenia by analyzing a patient’s seemingly senseless chatter (Spielrein’s dissertation case). Then, we learn about her ‘Transformation’ letters to Jung where she, for the first time, formulates her ground-breaking theory linking sex and death as one instinct evolved in nature for the purpose of propagation and species preservation. Both Freud and Jung were very much opposed to her linking biology and psychoanalysis, and, only now, a century later, her marriage of two fields of knowledge starts receiving an acknowledgement. Launer also discusses Spielrein’s peacemaking efforts at trying to unify all three psychoanalytic theories: Jung’s myth, Freud’s sex and Adler’s power theory. Eventually, she gives up. She was a scientist, not a politician.

Despite her family and country suffered immense losses in WWI and Civil War and she was herself left with hardly any means to existence, Spielrein continues her work, now in child psychology: she was first to listen and make sense of children’s language and publish the crucial papers on the matter a decade before her famous female colleagues, Melanie Klein and Anna Freud.

A colleague named Cifali wrote about Spielrein,

She’s praised for her moral qualities, her serene stoicism and her intellectual qualities.

Launer further talks about Spierein’s work in Russia, where her ideas influenced other prominent child psychologists, Vygotsky and Luria. He summarizes her phenomenon here,

‘Spielrein approached biology and sexuality from the viewpoint of a young woman who was both tempted by desire and afraid of it’

The final Russian period of Spielrein’s life was one tragedy after another. All of her brothers were killed during the period of Stalin’s repressions along with over a million of other people. The book’s penultimate chapter describes the death of Sabina and her daughters in the Holocaust in 1942. My eyes welled with tears as I was reminded of these atrocious episodes of our past. Watching daily news one can’t help but think that we haven’t learn anything from history.

Spielrein was indeed a remarkable woman and a phenomenal thinker, very much ahead of her time. She deserves a proper recognition, and we need a reminder of what great people the world had lost and how we indebted to them. This year, 25th of October 2015, the world will celebrate 130th anniversary of Spielrein’s birth. I hope her life and legacy will receive an appropriate and long overdue exposure both in Russia and abroad.

December 29, 2014

Russian Literature: Women and Love

Konstantin Makovsky [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

If something was chosen to represent the pride of Russia, it would definitely be the beauty, intelligence, resourcefulness, resilience of Russian women. And luckily, the modern women’s prose is well translated.

Natasha Perova, the founder of Glas publishing house

Firstly, I’d like to introduce you short story anthologies published by Glas. Starting with these books is the best way to sample fiction of various authors before trying their novels. A Will and A Way, Nine and Women’s View are three collections by Russia’s top female writers, including Rubina, Muravieva, Petrushevskaya and Ulitskaya. Russian Drama presents works by four emerging Russian female playwrights, while Still Waters Run Deep features stories by women in their 20s and 30s. War and Peace is a gender juxtaposition anthology, focusing on Russian life after perestroika. In the War, the male authors present their stories about the Russian army and the Chechen War, while Julia Latynina exposes corruption in the Russian Caucasus. In Peace, five female authors contribute stories of everyday life, with love, children and family being central themes here.

An Armenian-born Muscovite Nina Gabrielyan has written stories that are full of tragic surrealism that is presented to the reader, as if in compensation, through vivid and juicy prose. In the Master of the Grass, a short story collection, Gabrielyan explores loneliness and solitude, and fears, dreams and obsessions that are associated with them. Each of the stories has a different plot and characters: a narcissistic man, an Elderly Armenian couple’s memories of their tragic past, a lonely woman speaking with her flat. The uniting theme and atmosphere connects all of these stories into one reality.

An Armenian-born Muscovite Nina Gabrielyan has written stories that are full of tragic surrealism that is presented to the reader, as if in compensation, through vivid and juicy prose. In the Master of the Grass, a short story collection, Gabrielyan explores loneliness and solitude, and fears, dreams and obsessions that are associated with them. Each of the stories has a different plot and characters: a narcissistic man, an Elderly Armenian couple’s memories of their tragic past, a lonely woman speaking with her flat. The uniting theme and atmosphere connects all of these stories into one reality.

By Евгения Давыдова (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Dina Rubina, a Russian-Israeli author born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, has captured hearts of Russian readers with her bright, colorful like the Istanbul grand bazaar, writing style. Rubina is a self-critic; she once said that she lives in a state of a permanent ‘creative crisis’. In my opinion, this is a sign of the never-ending writer’s growth. Several of her books have been adapted for screen. Although female protagonists and women’s life are often central to her fiction, in novels like Leonardo’s Handwriting or On the Sunny Side of the Street, her most known novel translated into English remains the award-winning Here Comes the Messiah , set in the modern-day Israel. The focus here is not political, but human. The book is satirical and surreal; as an outsider who came to live in Israel in mature age, Rubina had the required distanced viewpoint to portray the absurdities of life on the West Bank.On Upper Maslovka is a signature work of women’s prose from Rubina. Anna Borisovna is an 87-year-old yet vigorous woman with a stingy, sarcastic tongue, who used to be a famous sculptor, ‘the old woman is rude as a drunk pathologist’. Peter is a young theatre director, failing to make it big in the art world. Their creativity brought the two together, but their love is far from platonic. A case of people falling in love despite being generations apart from each other is not uncommon. Here it is complicated by Peter’s unfulfilled ambitions and the intellectual class occupational hazards of the characters, such as cynicism and existential angst. Rubina’s works are available in many languages, including Polish, German, Hungarian and French.

source: https://pages.shanti.virginia.edu/rus...

The theme of love and creativity is also explored in Maria Stepnova’s book, The Women of Lazarus, which follows the life and three loves of Lazarus Lindt, a genius nuclear physicist. It starts straight after the Russian revolution, in 1918. Lazarus is like a son to a childless couple, Marusya and Sergei Chaldonov. Yet he loves Marusya like a man, with a secret love, of which she’s not aware. When he becomes a famous scientist Lazarus falls for young Galina, and yet again it’s a love that is not meant to be. Sometimes, there can only be one love that occupies a man’s heart. Lazarus’s devoted to science but the fate gives him a gift, reincarnating Lazarus’s genius in his granddaughter Lidochka. A French and a German translations of this award-winning novel are out now.

By Евгения Давыдова (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Ludmila Ulitskaya is one the most well-known modern Russian authors focused on the Soviet Period and family life. Many of Ulitskaya’s protagonists are women. In Sonechka, an innocent librarian girl falls in love with a man who becomes her husband, and her love as pure in most romantic books she’s been reading, devoid of egoism. The reality may be grey, but Sonechka lives in the bright world of words. May be it’s not a silly escapism, as the reality we live in, we create ourselves. Another novel by Ulitskaya, Medea and Her Children, is set in Crimea. Medea is an old childless woman and yet a head of a big family, patching up harmony within it with her love and wisdom.

Another modern Titan of Russian women’s prose is Irina Muravieva. Her books often contain parallel plots, rhythmic prose, synesthesia and spirituality. Two of Muravieva’s novels have been translated into French. Le Journal Intime de Natalia (Natalia’s Diary) is a sad story of solitude of an abandoned and impoverished woman, whose only loyal friend is her old dog. Portrait de Bindo Altoviti (Altoviti’s Portrait) is a story of an ex-pat family that moved from New York to Moscow: a mother and a daughter, love and suffering, love and death, and a new Christ. The novel has Muravieva’s inherently poetic, melodic language, well suited to balance the overwhelming emotions of its characters with a philosophical tone.

source: http://www.books.glagoslav.com/the-ti...

A celebrated St Petersburg author Yelena Chizhova has won the Russian Booker in 2009 with her novel, The Time of Women, recently translated into English and German. Antonina, a female worker from the province, comes to conquer Piter (the Russian nickname for St Petersburg), but there she is seduced by a handsome man, gets pregnant and eventually dies, leaving his daughter for upbringing to three grannies, neighbors in the communal flat. Antonina’s baby girl Suzanna grows up, becoming an artist, and along with her story we learn about lives of her ‘mothers’ who survived the Revolution, the WWII, the blockade and Stalinism.

source: Goodreads

Probably the most scandalous book written about Russian women is… not Nabokov’s Lolita (who was not Russian). It is Victor Erofeyev’s Russian Beauty. The novel was written in the early 1980s, but it was published a decade later and quickly found international fame, having been translating into over twenty languages. In this story, after a failed marriage, a young bisexual woman, Irina Tarakanova, comes from the province to Moscow to work as a fashion model. She is a prostitute, who used to be repeatedly raped by her father as a child. Irina likes perverse sex and has many lovers. After a scandalous pornographic photo-session, Irina loses her job and decides that her life in Russia is awful. She performs exorcist acts, running naked in the wild and getting very sick. Not to give any more spoilers, I’ll just say that things spiral out of control, with the story ending in the most decadent way. I ask myself this question over and over again: why the world is so much fascinated with postmodern horror stories coming from Russia? Is this Russian girl an allegory of the country itself plagued by wars and revolutions, raped by Bolsheviks and Stalinism, exorcised by propaganda and given a hope of a glorious afterlife by its Church? Beauty may have an ugly side.

source: Glas

Finally, I would like to mention Anna Babyashkina’s speculative fiction novel Before I Croack that won the Debut Prize in 2011. Set in the near-future Russia in 2039, where people are still using social networks like Facebook and Live Journal, the story focuses on ambitious pensioner Sonya who was sent by his son to a retirement home, The Mounds. Sonya finds similar minded contemporaries who have grand ambitions to write the next Great Russian novel. The author called her book a letter to our generation from the future. Maybe it was meant to show uselessness of our urban generation, spending life on the Internet, and our not-so-bright future, which reminds us the present. Is this a hint on another Zastoi taking over our society (a Soviet era of Stagnation under Brezhnev’s rule 1964-1982)? Or is it simply a seasonal hibernation? At least once a century, the overbearing Russian bear (alliteration intended) needs his sleep.

P.S. This was a chapter excerpt from my upcoming guide on modern Russian literature. I’m still doing final edits of it, please bear with me, I’ll release it very soon.

More on Russian women’s prose here: Women conquer Russia’s literary Olympus

P.S.S.

I’m delighted to announce that on Christmas Eve, a Chinese translation of my novel, Mr Right & Mr Wrong, was published as an ebook by Douban Read.

December 22, 2014

Merry Christmas!

I hope you are all enjoying Christmas time festivities. To cheer up everybody to stratospheric heights, I have written a new Christmas song, this year – a happy one.

I wish you all good health and great accomplishments in the new year!

Merry Christmas!

December 12, 2014

Chloe’s Christmas in Heidelberg: fun excerpts from Mr Right & Mr Wrong

Christmas is coming and I decided to post here two Christmas scenes (set in Heidelberg, Germany) from my romantic comedy, Mr Right and Mr Wrong.

It’s dark when we reach the market square where the fair is taking place. Trish has already taken hundreds of pictures on her phone.

It’s dark when we reach the market square where the fair is taking place. Trish has already taken hundreds of pictures on her phone.

“My fingers are numb. Kurt.”

“I refuse to pose any more anyway.” He looks so cute in his reindeer head hat, which has long, blood-red antlers sticking out from it.

“No, what I meant is, me and Chloe would like to try this cherry glue-wine. Hmm, funny name. And we need pretzels.”

“Thank you, Almighty,” Kurt says. “Those will keep you busy for a while.”

I’m a little jealous of Trish. I’ve never met anyone who enjoys Christmas as much as she does. We’ve only just arrived but she’s promptly befriended dozens of guys on Facebook, most of them American soldiers stationed here.

“Guten abend,” she says to a newly found victim in the guise of a young seller of wooden figurines. At that, her German vocabulary is exhausted. “What’s your name?”

“Kurt,” he replies smiling.

“O.M.G. Chloe, we need to make a wish. Another Kurt. Come over here,” she orders our Kurt.

As a gesture of gratitude to the craftsman she buys a whistle in the shape of a finch.

“What?” she says when both Kurt and I roll our eyes. “I needed a rape alarm anyway.”

“Darling, you’re quite alarming enough by yourself.”

“Don’t be mean, Chloe. I think it was a great idea to get this,” she replies and blows into the whistle. “It works well, doesn’t it?”

This must be an understatement of the year, I think, as my right ear is taken out of action…

***

I wake up with an astonishing clarity in my head to match the cloudless azure sky. No hangover whatsoever; it must be a Christmas Eve miracle. Or, more likely, bloody good German beer.

I slip from the bed and spot Kai sunbathing on the windowsill. The snow carpet looks renewed, and the twigs of the trees sparkle with their crystalline coat. I hold my breath.

It’s perfect weather for jogging. I try to wake Trish, but she mumbles something offensive and burrows further under the blankets. I persist for a while longer until her hand protrudes and makes a rude gesture.

My next move is to persuade Kurt to join me.

“Go away! I’m on holiday!” He throws a cushion at me and I retreat to the corridor before he decides to use heavier objects.

There’s nothing wrong with solitude. It’s therapeutic when prescribed in moderation.

I put on my skiing holiday outfit, which I haven’t used for several years but brought with me in case an opportunity to wear it arose. It still fits, thanks to my recent gym sessions.

The roadside path is already cleared, so I don’t have to jog through knee-high snowdrifts. I run up the hill first; it’ll be easier to descend on the way back. The air is crisp and smells of conifers, which are abundant in the nearby park.

I recall yesterday’s conversation with Calvin. It must be rewarding to dedicate your life to science and then enjoy retirement in a serene place like this. I realised I didn’t ask him about his life. Does he have a wife? He mentioned that he’s a father. I hope he’s happy and loved by his family. And I must find that peculiar French book.

On my left there’s a clearing with a stunning view of the old town, the river and its bridges. I take out my phone to take a shot and notice a new text message from Terrence.

I think I love you, Chloe. Merry Christmas.

Does it mean he misses me so much he’s sent his greetings a day early? I shall reply tomorrow. Hopefully, I can figure out what to say.

After a quick photo session featuring some clumsy self-shots I’m ready to turn back. My serenity is now destroyed and I start feeling hungry. I wonder what Irma has made for breakfast. I must offer her my help. The last thing I want her to think is that Kurt lives with two lazy, shallow, useless prima donnas.

I need to stay completely immersed in the festivities and remove Terrence from my mind while I’m here. But that’s easy to say. All I have to do is to reply, “I love you too.” Would it be a lie?

I’m not so sure I’m in love with him. I can’t tell whether it’s because of Blake or the fact that Terrence and I haven’t spent enough time together. Well, the Paris holiday should make things clear. Hopefully.

With a hundred metres to go I discover my second wind and speed up. A hot shower and coffee and cuddles with Kai are on my mind when I’m suddenly hit with a snowball. I stop and see a shoulder-high wall of snow erected in front of Kurt’s house’s entrance. Trish emerges from one side of it and throws another snowball at me.

“You just wait,” I shout and laugh.

If someone wants her arse kicked, well, she’s getting it now.

I take a handful of snow, staring apprehensively at the wall, and make my first weapon.

Trish emerges again and we throw simultaneously. I hit her in the fanny and she misses me. I jump yelling ‘Yay’ and get hit on the thigh by Kurt, who’s been hiding behind a tree next to the wall.

Oh, so you ganged up against me? The wrath of Chloe shall be unleashed upon you then. Relentlessly.

I hide myself behind Erwin’s car and prepare four snowballs, two of them I hide in my pockets and another pair I hold in my hands. The task is to get to the house and neutralise the enemy on the way.

When I slowly stick my nose out from behind the car, I see Trish lying on the top of the wall, head propped on palm, holding a snowball with her other hand.

I spring towards her, shoot at my target and miss. She throws hers at the same time as I do my second one. I miss again while she hits me in the shoulder. She’s falling off the wall, carried forward with her throwing force. I laugh and rummage through my pockets for new supplies when I’m hit again, this time by Kurt’s ammunition.

I respond but only manage to ‘injure’ the tree. It appears he’s stocked up on ammo as I’m hit twice again within seconds, and then Trish recovers and sends another snowball my way.

I’m on the verge of despair and losing the battle when a car arrives and stops next to Erwin’s. Two lads, who both look to be twenty-something and are presumably Kurt’s relatives, join the battle. The enemy hides behind their fortification to concoct a new evil plot, while my two new allies, David and Derek, get busy alongside me making snowballs after brief introductions. They are to take care of Kurt and I’m to deal with Trish.

“Stop hiding, you bunch of sissies,” Trish shouts at us. A massive snow missile lands a metre from us.

Time to put an end to this.

The lads and I come out simultaneously and charge in a line. Derek leads and takes most of the impact on himself, while I’m safely in the tail.

Halfway through we separate: the guys attack Kurt while I keep running and crush into Trish’s hiding place. The wall crumbles into several chunks and I land on top of Trish. We both start laughing hysterically.

“Chloe, we got him!”

I look up and see the lads approaching us and carrying Kurt by his arms and ankles, akin to a live stretcher.

“Get off me. I’ll kill you next time!” he wails.

“No, you won’t.” Derek and David swing his body like a hammock and then throw Kurt into the nearest snowdrift.

At last, I’m avenged.

***

Mr Right & Mr Wrong is available from major retailers in print and ebook formats.

December 8, 2014

Religion in Modern Russian Literature

In 2012 an unlikely book exploded bestseller charts in Russia, easily outselling its close competitors. It is a collection of stories about life of the Russian Orthodox Church called Everyday Saints and other stories. In some of these, the author, Arkhimandrit Tikhon, described his path of becoming a clergyman and his early life in the Pskov-Pechora monastery. Parables and sermons are a usual part of such books, which are quite abundant in Russia. So what made Everyday Saints stand out? Arkhimandrit Tikhon gives us a clear and authentic portrayal of the monastery life with humour, drama, a very human perspective. In fact, some stories of the clergymen here are told in quite an unvarnished way. They often contain angry outbursts, foul language; they seem almost anti-religious.

Indeed, Arkhimandrit Tikhon doesn’t try to convert anyone. Instead, he shows everyday life of ‘invisible’ saints. And people’s path to faith.

Indeed, Arkhimandrit Tikhon doesn’t try to convert anyone. Instead, he shows everyday life of ‘invisible’ saints. And people’s path to faith.

The literary establishment regarded the author’s prose with a high esteem too, pointing out logical and elegant structure of these stories. A writer Alexander Prokhanov even called the book’s genre monastery prose. Everyday Saints are now available in translation in many languages, including French, Polish, German and Chinese.

Now imagine a story collection about the Russian Church yet written by a philologist and literary critic. There is one and it is Maya Kucherskaya’s Faith and Humour. It was quite a bold decision to write and publish it, knowing the daunting and opinionated Russian readership. Behind all the humour, sometimes very black, there is genuine sincerity and appreciation of the church life here.

In one of the stories, The Good Man, Kucherskaya features different priests: one – alcoholic, another – nonbeliever, there’s a thief, homophob, misanthropist, there is also a saint. Many of these miniatures are parables with a real life story behind it. For instance, there is one about an Orthodox hedgehog that was baptizing a squirrel, and it drowned. Russian Church in Kucherskaya’s stories is diverse and complex as life itself. Many considered the book’s humour is rather poisonous, I think it’s therapeutic. Perhaps, Kucherskaya simply shows that faith should not be equaled to people of faith who may sin like everybody else. A job in a church institution doesn’t make one a saint or superior human being.

In one of the stories, The Good Man, Kucherskaya features different priests: one – alcoholic, another – nonbeliever, there’s a thief, homophob, misanthropist, there is also a saint. Many of these miniatures are parables with a real life story behind it. For instance, there is one about an Orthodox hedgehog that was baptizing a squirrel, and it drowned. Russian Church in Kucherskaya’s stories is diverse and complex as life itself. Many considered the book’s humour is rather poisonous, I think it’s therapeutic. Perhaps, Kucherskaya simply shows that faith should not be equaled to people of faith who may sin like everybody else. A job in a church institution doesn’t make one a saint or superior human being.

Quite a different view on religion is presented in Ludmila Ulitskaya’s Daniel Stein, Interpreter. Daniel Stein was a Polish Jew who survived Holocaust by working as an interpreter for the Gestapo and after the war he moved to Israel and became a priest. What a life! The book can be considered as a fictionalized biography, as it is based on the real-life Carmelite priest. Here one can find some curious interpretations of Biblical myths and, of course, Holocaust is also discussed. The novel is mainly about people who met Brother Daniel and stories of their scarred lives.

Quite a different view on religion is presented in Ludmila Ulitskaya’s Daniel Stein, Interpreter. Daniel Stein was a Polish Jew who survived Holocaust by working as an interpreter for the Gestapo and after the war he moved to Israel and became a priest. What a life! The book can be considered as a fictionalized biography, as it is based on the real-life Carmelite priest. Here one can find some curious interpretations of Biblical myths and, of course, Holocaust is also discussed. The novel is mainly about people who met Brother Daniel and stories of their scarred lives.

A theme of faith is touched in Evgeny Vodolazkin’s award-winning Laurus. Set in a medieval Russia, this story tells a spiritual journey of a healer aiming to live the life for his late beloved he couldn’t save. Initially prompted to act by guilt and need for self-sacrifice to atone his sin, Laurus goes on helping people out of love and confession. This is a story of a Russian saint. An Italian translation of this novel titled Lauro is available now.

A theme of faith is touched in Evgeny Vodolazkin’s award-winning Laurus. Set in a medieval Russia, this story tells a spiritual journey of a healer aiming to live the life for his late beloved he couldn’t save. Initially prompted to act by guilt and need for self-sacrifice to atone his sin, Laurus goes on helping people out of love and confession. This is a story of a Russian saint. An Italian translation of this novel titled Lauro is available now.

Post-Soviet Russia is an eclectic spiritual space. Officially dominated by the Orthodox Church, the country nevertheless is still very much a realm of atheism, the Soviet legacy. And what religion would find such soil fertile, – an atheistic one. Buddhism is popular not just in Russia, for it gives every person a chance for enlightenment, a chance to reach nirvana and become a superhuman, a God.

Post-Soviet Russia is an eclectic spiritual space. Officially dominated by the Orthodox Church, the country nevertheless is still very much a realm of atheism, the Soviet legacy. And what religion would find such soil fertile, – an atheistic one. Buddhism is popular not just in Russia, for it gives every person a chance for enlightenment, a chance to reach nirvana and become a superhuman, a God.

Of all modern writers, Victor Pelevin has probably done the most to adapt Buddhism to Russian mentality. The critics even say that the author’s interpretation of it is very much wrong. In Buddha’s Little Finger and The Sacred Book of the Werewolf, Russian history and politics in relation to life of ordinary person are viewed through the prism of Buddhism and Russian humor. I can only guess to what extent either of those can be translated into another language.

Of all modern writers, Victor Pelevin has probably done the most to adapt Buddhism to Russian mentality. The critics even say that the author’s interpretation of it is very much wrong. In Buddha’s Little Finger and The Sacred Book of the Werewolf, Russian history and politics in relation to life of ordinary person are viewed through the prism of Buddhism and Russian humor. I can only guess to what extent either of those can be translated into another language.

In Pelevin’s yet-to-be-translated novel called t, a metaphysical detective story featuring Count Tolstoy as a main hero and a sleuth, literature itself becomes an object of philosophical dissection with the tools being Zen Buddhist and Confucian doctrines. Pelevin doesn’t take religion too seriously though; maybe this is what makes him very Russian. How one can take life, this bizarre thing, so seriously?

Check out this quote from t,

Our mind is a crazy monkey, running towards profundity. And the thought that our mind is a crazy monkey, running towards profundity, is nothing else but a skittish attempt of the monkey to correct her hairdo on the way to the abyss.

If this is too deep for some, there is always another Russian mean to reach enlightenment, which doesn’t require much intelligence, – vodka.

***

Perhaps, you’ve noticed I’ve recently started surveying new Russian books in a systematic manner. These are the ‘sneaky peek’ materials, taken from my upcoming The Reader’s Mini-Guide to Modern Russian Literature, which I’m busy editing at the moment. I plan to release a beta-version of it to my blog subscribers in a few weeks time, so you will all have an opportunity to read it and suggest things for the final version, which will be released early next year. The print edition will be launched at the next London Book Fair. So, if you haven’t subscribed yet, this is good time to do so (in top left corner of the page under my photo) and receive this free guide first amongst other readers.