John C. Wright's Blog, page 136

March 23, 2012

Here is What You Should be Doing This Weekend

That is, if you are serious about liberty.

http://standupforreligiousfreedom.com/

Once freedom of conscience – for anyone, of any denomination or none at all- goes, all freedoms go.

If the state can command you to do an act your church or your philosophy teaches is deeply immoral act on the grounds that the common good demands, by the same logic, on what grounds can you object should the state command you to speak or print or think as the common good demands?

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 22, 2012

Nor the Summers as Golden by Gene Wolfe

An excerpt from Gene Wolfe's mediation on how to write a multi-volume novel. The original is here: http://www.gwern.net/docs/2007-wolfe

Since just last night I encountered a grave difficulty with my own multivolume work THE UNWITHERING WORLD with the setting, I thought it was providential that I should come across this. The words below are Wolfe's (or Homer's or Kipling's) but not mine, and he is the finest novelist alive today, in or out of genre.

Nor the Summers as Golden: Writing Multivolume Works

by Gene Wolfe

How do you write stories too big for one book?

That is the question I am supposed to answer here, and I ought to confess at once that I may know no more about it than you do. Indeed, I may well know less. My only credential is that I have completed two such works – The Book of the New Sun (four volumes and a coda), and The Book of the Long Sun (four volumes). I, myself, would not read an article on novel-writing by someone who had written two.

Fundamentally, you create these large works by writing something that is more like life itself than the other forms are. Or so it seems to me. In short stories we typically separate a few hours – a single day at most – from the years of the characters. (In 1972, Gardner Dozois edited an anthology called A Day in the Life; that is it, exactly.) A carriage will flee, through ever-deepening snow, a French town occupied by the Prussians; in it ride a great nobleman and his lady, some rich merchants and their wives, a red-bearded beer-swilling radical – and the plump and patriotic little whore the townspeople call Boule de Suif. The driver cracks his whip; a full half dozen horses lunge against their harness; our carriage flounders and skids, and we're off!

The story, as the reader realises at once, begins with the cracking of the whip and will end when the passengers reach Le Havre.

No doubt one out of the half dozen members who read this will want to be told what a novel is as well, with Huckleberry Finn or For Whom the Bell Tolls as examples. I apologise and beg to be excused. The vast majority of our members, including the other five, read nothing else, and most write nothing else. They do not need to be told what a novel is; they need to be told what the other things are; and that, after all, is what I'm supposed to do here.

One of the other things, to pedants if to nobody else, is the series; but a series is nothing more than a succession of novels that are all too often progressively weaker. You write a novel, and because it sold, another about the same person or persons, until at last your editor warns you Not To Do That Any More. (I cannot present myself as a model of virtue in this regard, much as I'd like to; I've done it, and I'll probably do it again if I get the chance.)

A trilogy, tetralogy, hexology or whatever is very like a series, superficially – so much so that it is often mistaken for one by reviewers; but there are deep-seated differences. And a series, which is much easier to write, is actually much harder to write well.

A multivolume work sets out to tell a multitude of stories under the umbrella of a single overshadowing story. You will be tempted to quibble here, if only with yourself. Telling 'the story of Main Character's life' doesn't count. Everyone is born at the beginning and dies at the end, although it would be both possible and legitimate to write the story of how Main Character came to die; The Lord of the Rings, which is a genuine trilogy, comes very close as it tells how Frodo rid himself of the one Ring.

By now you have come to see – I hope – why a series is at once easier, and more difficult to write well. It is easier because the author need not worry throughout several books about the overshadowing story that should be lurking in the background of all the subsidiary stories. Contrariwise (as Tweedledee says somewhere in the two-book Alice series), a series is harder to write well because its individual books lack the unity and sense of purpose that an overshadowing story would confer.

From what I have said, it should be obvious that one of the first things the author of a multivolume work ought to do is decide upon the over-shadowing story and tell the reader what it is to be. Thus Homer sets out to tell – and does tell – the tale of the rage of Achilles, with a multitude of subsidiary stories about funeral games, the fighting before the walls of Troy, and so on and so forth. Have you forgotten the opening?

Here it is:

Achilles's wrath, to Greece the direful spring

of woes unnumber'd heavenly goddess sing!

That wrath which hurl'd to Pluto's gloomy reign

The souls of mighty chiefs untimely slain;

Whose limbs unburied on the naked shore,

Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore;

Since great Achilles and Atrides strove,

Such was the sovereign doom, and such the will of Jove!

Notice how much Homer has packed into those few opening lines. What is the overshadowing story? Achilles' wrath, mentioned in the first line. Who is Main Character? Achilles, of course, who is mentioned twice in this brief beginning. Can we expect divine meddling in the story? Yes, indeed! 'Heavenly goddess sing', and 'the will of Jove'. Those unburied bodies promise war, and 'the naked shore' hints of the sea. If, after reading all that, you do not understand that Homer was of our trade, you do not understand our trade. Here are a few lines from someone who understood it perfectly:

When 'Omer smote 'is bloomin' lyre,

He'd 'eard men sing by land and sea;

An' what he thought 'e might require,

'E went an' took – the same as me!

Yours is a higher and holier calling, perhaps; all honour to you. But I am of Homer's trade, and Kipling's, admittedly on a rather more modest plan; and the moment Homer opens his Iliad, I recognise a member of our lodge. If you have not read him, you ought to, remembering always that he knew exactly what he was doing. (Yes, almost three thousand years ago.) He knew it, because he had recited those verses scores of times to live audiences. If he bored or otherwise displeased his hearers, there would be no soup and no bread for the blind minstrel who wandered from great house to great house. The Iliad is, of course, a multivolume work; if you don't believe me, examine its structure. If you still don't, compare its length to those of other poems, including Greek poems.

Now we have reached the hard part, for all the familiar chores of the novelist are the same. You must chose a time and a setting, create engaging characters, provide dialogue that will be succinct and interesting, and the rest of it. You know the drill. You must conclude each of your books in a way that will provide a sense of finality, obviously without prematurely ending the overshadowing story, which will furnish an ending for the last. Thus in The Book of the Long Sun, the first volume ends with Silk's recognising his need to confront his own nature, the second with the death of Doctor Crane and Silk recognised by officers of the Civil Guard as the legitimate head of the city government, the third with Silk installed and functioning as head of the government, and the fourth with his salvaging the people originally committed to his care from the ruin of their city and their world – this last being the overshadowing story told in the four books. But all that is easy enough. Your own psychology presents the chief difficulty, and frequently requires a good deal of doublethink. You must keep in mind that the overshadowing story is to be told in half a million words or so – while forgetting that years of steady effort will be required to write them. There is a temptation, often severe, to wind the various plots up too quickly. There is another, often insidious, to pad. Half a million is a very large number indeed.

But not as large as you might think.

[...]

There is one final point, the point that separates a true multivolume work from a short story, a novel, or a series. The ending of the final volume should leave the reader with the feeling that he has gone through the defining circumstances of Main Character's life. The leading character in a series can wander off into another book and a new adventure better even than this one. Main Character cannot, at the end of your multivolume work. (Or at least, it should seem so.) His life may continue, and in most cases it will. He may or may not live happily ever after. But the problems he will face in the future will not be as important to him or to us, nor the summers as golden.

Read the whole thing here: http://www.gwern.net/docs/2007-wolfe

—————————————————–

Here is the full text of the Kipling poem quoted:

"When 'Omer Smote 'Is Bloomin' Lyre"

INTRODUCTION TO THE BARRACK-ROOM BALLADS IN "THE SEVEN SEAS"

When 'Omer smote 'is bloomin' lyre,

He'd 'eard men sing by land an' sea;

An' what he thought 'e might require,

'E went an' took -- the same as me!

The market-girls an' fishermen,

The shepherds an' the sailors, too,

They 'eard old songs turn up again,

But kep' it quiet -- same as you!

They knew 'e stole; 'e knew they knowed.

They didn't tell, nor make a fuss,

But winked at 'Omer down the road,

An' 'e winked back -- the same as us!

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

Victory at Bookspotcentral! On to more Voting!

Well, well, against all hope and expectation, the lovely and talented Mrs Wright prevailed against Geo RR Martin's novel in the first round of the March Madness at Bookspotcentral.

She writes:

Thanks so much for your support so far. I have made it to Round Three of the contest. Here is the link for voting. (I am up against The Clockwork Prince, which is a pretty big book.)

Remember, every member of your family, including pets or hitchikers, may vote. You may need to erase your cookies between votes, or have each family member use a different computer from a different IP address. Carefully hold your dog's paw to the keyboard, and make sure to hit the right key.

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 21, 2012

Gallantry

Gallantry is dead, and it is thanks to those alleged defenders of womenkind and all things weak and poor, the Politically Correct. Except that the PC-niks does not have a good track record of kindness to women, do they?

Here is an exhibit:

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/bristolp...

Dear President Obama,

You don't know my telephone number, but I hope your staff is busy trying to find it. Ever since you called Sandra Fluke after Rush Limbaugh called her a slut, I figured I might be next. You explained to reporters you called her because you were thinking of your two daughters, Malia and Sasha. After all, you didn't want them to think it was okay for men to treat them that way:

"One of the things I want them to do as they get older is engage in issues they care about, even ones I may not agree with them on," you said. "I want them to be able to speak their mind in a civil and thoughtful way. And I don't want them attacked or called horrible names because they're being good citizens."

And I totally agree your kids should be able to speak their minds and engage the culture. I look forward to seeing what good things Malia and Sasha end up doing with their lives.

But here's why I'm a little surprised my phone hasn't rung. Your $1,000,000 donor Bill Maher has said reprehensible things about my family. He's made fun of my brother because of his Down's Syndrome. He's said I was "f—-d so hard a baby fell out." (In a classy move, he did this while his producers put up the cover of my book, which tells about the forgiveness and redemption I've found in God after my past – very public — mistakes.)

If Maher talked about Malia and Sasha that way, you'd return his dirty money and the Secret Service would probably have to restrain you. After all, I've always felt you understood my plight more than most because your mom was a teenager. That's why you stood up for me when you were campaigning against Sen. McCain and my mom — you said vicious attacks on me should be off limits.

Yet I wonder if the Presidency has changed you. Now that you're in office, it seems you're only willing to defend certain women. You're only willing to take a moral stand when you know your liberal supporters will stand behind you.

This is a quote from Bristol, daughter of Sarah Palin, whom I do not recall being treated in a civil fashion by the Leftist media in recent years.

Do you understand what is happening? Because a mother did not kill her baby in the womb, that is, did not perform an act of abominable child-murder against her own baby, the PC-niks have scrupled at nothing to harass, revile and slander her and her family.

Why are these creatures running our nation? How have they come to dominate our culture?

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 20, 2012

A Dying Planet

Over at the NRO Corner, one Michael Austin writes:

So, John Carter is shaping up to be the Ishtar of the 2010s, the Gates of Heaven of the Obama years. Disney is taking a $200 million bath on a movie that cost nearly a third of a billion dollars to make. Who would ever green-light such an absurd amount of money for a project whose original fans were driving Model T's and listening to the organ while watching the latest moving picture from the Lumiere brothers?

Allow me to answer the question. Material from 1912 is (a) in the public domain and (b) if it has lasted a century, it is good stuff. The smothering mustard gas of modern realistic fiction had not found its way into the pulps, where the heirs of all the ancient epics and heroic ballads of old where to be found.

Yeah, but what else you got? Sherlock Holmes? Narnia? Middle Earth? Hollywood's business model is to take a story that cost two shillings and thruppence-ha'penny and spend a fifth of a billion making it lousier. Sometimes it pays off, sometimes it doesn't, but either way the industry's living off Model T fumes. Hollywood could use its own Edgar Rice Burroughs, but instead it's a business full of guys who can't even adapt Edgar Rice Burroughs for less than 300 mil — and then blow it.

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 19, 2012

The Linnaean Taxomony of Femininity

ADDENDUM to the previous essay:

I had originally intended, but thought it unnecessary, to provide other examples of other types of femininity aside from anthropomorph schoolgirl-puppies and kawaii all-schoolgirl singing groups.

But more than one readers' comment to that essay caution me that some readers will always interpret the statement "X is feminine" to mean "X equals feminine" not "X is a member of feminine, of which there are more members than X."

The reason why I did not emphasize the obvious is that I thought it was too obvious to mention. The question being addressed was whether femininity existed at all; logically a single example suffices to disprove a universal negative. I only need to show you one Tasmanian tiger to prove Tasmanian tigers exist.

But, for the sake of those readers who are puzzled about the meaning of previous essay, please note it is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all feminine characteristics both physical and spiritual. I am confident that women other than anthropomorphic puppy-girls and saccharine-sweet cutie-pie schoolgirl singing groups exist. I believe Victoria, Queen of England, for example, was not a member of an all-schoolgirl singing group, or, at least, not during the later part of her reign. Perhaps she was a member of an all-girl Goth band or something.

It is unnecessary to remind me, or any thoughtful man, that the specific members participating in an archetype are distinct from that archetype and exhibit specifics not found in it. That is not only obvious, it is what the word "archetype" means. The Platonic ideal of a triangle is not the same as the triangular window made of glass in front left of the driver's seat of the used Oldsmobuick I owned in 1988. We all understand the concept of Platonic ideals and specific examples, where the specific has characteristics other than those the pure ideal version implies.

However, this does not mean archetypes or stereotypes or ideals do not exist, nor does it imply that there is something untoward or illogical or insufficient in referring to them. If I say, "my car window is triangular" to a man who thinks triangles don't exist, it is no argument to retort that other windows are rectangular, nor is the caution lest someone thing the word "triangular" means "car window" needed.

That said, allow me to propose to any readers unfamiliar with the existence of half the human race a simple Linnaean classification of some of the more prevalent or obvious or memorable archetypes into which women tend to fall.

I propose in brief that the pagan goddesses of old, if they did not reflect or represent a common idea or perception of certain stock feminine types, would not have been popular enough to be remembered from generation to generation.

The first is the Junoesque, who is both queen and mother of gods and men.

Juno

Now, I do not believe anyone regards Junoesque women to be unfeminine, but this is the Internet, so let us find a more pop culture version or something to make the point. There is nothing remotely schoolgirlish or puppyish about the celestial queen, but I defy anyone to make an argument that maternity or queenliness is a masculine role.

Hera

Are there any real women who come across as Junoesque?

Sophia Loren as Ximena in EL CID

While Homer portrays Juno or Hera as something of a shrew wounded by her husband's adulteries, his is not the only interpretation of what a heavenly queen is like.

Madonna and Child

So we can adduce a second type of femininity, called the Marian, which encompasses everything from the Queen of Heaven to the humble handmaiden of the Lord, to a Mother to a Virgin. Obviously virgins who are also mothers are rare on Earth, so returning to our classical mythology, let us select another virgin for our next type.

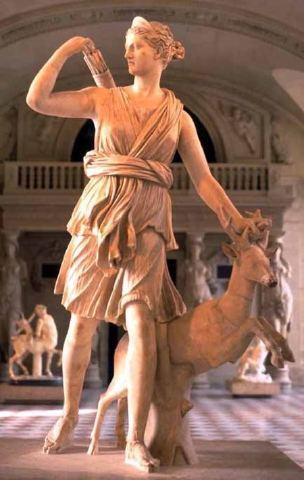

Artemis

Again, this looks plenty feminine to me, even thought the chaste goddess of the chase engages in what of traditionally a masculine sport of hunting game.

What real women would I place in the Artesian category? While nearly any female athlete would do, I am a geek, so I will pick an actress from a fantasy movie.

Queen Susan the Gentle. Shoot them, Sue!

Is Artemis the only virgin from classical mythology? By no means.

Virginal Athena

Athena is a favorite goddess of mine. Fewer arbitrary acts of cruelty are told of old of her than others of the pantheon, and she is a patron of philosophers. It particular amuses me that the Christians are often chided by the Sexual Revolutionaries for praising and upholding virginity as a female ideal, when, of course, this is a human thing common to all races and nations of man, not something particular to Christians.

The Athenian archetype of womanhood includes two archetypes of its own: the wise woman and the warrior woman. Any bookish woman, bluestocking, scientist or scholar partakes of something of the first.

Chris Fisher as Girl Genius Agatha Heterodyne

For those of you who don't recognize her, this is a Agatha Heterodyne from GIRL GENIUS, as portrayed by good friend Chris Fisher. But any female scientist would fit the bill as well, such as Madame Curie:

Okay, that is not really Mme Curie. I hope.

And, of the second aspect of Athenian femininity, the Martial Maiden is perhaps the most common archetype most favored by our modern pop culture, almost to the exclusion of all other female types:

Nicole Leigh Verdin in SHROUD

Leelee Sobieski as Joan of Arc

Wonder Woman in Wonder Bra Armor

Note that only the cartoon image above is wearing a metal battle-bikini. The other two images show something more like what Joan of Arc or Elizabeth I might have worn to visit a battlefield, rare as it was for women to be found on battlefields before the invention of the firearm or "equalizer."

Nicole Leigh Verdin with Equlizer

While the Athenian image of the Martial Maiden is a popular one these days, one reason for its popularity is that modern women serve in the military more frequently than previous generations.

Spc. Jennie Baez of the the 47th Forward Support Battalion in Iraq with heavy caliber Equalizer

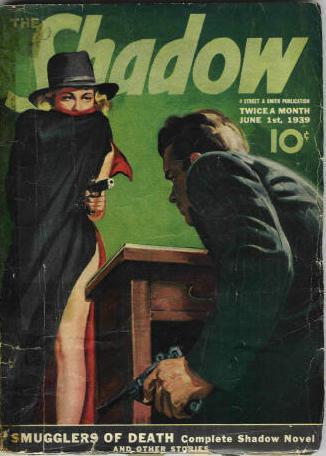

There is many a maiden who has need of an Equalizer. Despite what you've been told, the depiction of women in old pop culture did not ignore this archetype.

A Dame and Her Equalizers

In the old days, the armed female was actually relatively common. I am puzzled, but not surprised, at the tenacity with which the story is spread that women were always portrayed as damsels in distress in the previous generation. I have not formed anything like a rigorous survey, but I have seen old magazine covers:

Indeed, Biblical and Classical sources show the archetype existed since the dawn of history, the only difference being that its rarity was recognized as normal rather than as evidence of some extraordinary repression of a natural desire in women to commit acts of war and murder.

Judith Decapitating Holofernes

Note Judith in the picture above wincing at the butchery.

Yet another virginal goddess, ironic considering her role, is the eldest and first of all the children of Saturn is Vesta, the goddess of hearth and home, the earth mother herself. Vesta is sadly disregarded in pop culture cartoon versions of the pantheon of old: I cannot recall seeing her in those well researched and scholarly portrayals of Greco-Roman mythology known as Hercules the Legendary Journeys or Woman Woman comics.

While the vestals were virgins and keepers of the sacred flame, Vesta herself was the goddess of motherhood.

Vesta, Goddess of the Hearth

Vesta the earth-mother is an archetype most disliked in pop culture these days, even as the archetype of the Martial Maiden is the most venerated. Gaea, Rhea, Demeter, and in some ways Proserpine all partake to a degree of this same basic feminine archetype.

Demeter the Grain Goddess

I am sure there is some version of the maternal type in pop culture. Let me see.

June Cleaver

And, as an opposite number to the matrimonial Juno and the virginal goddesses, we have the Venereal archetype, the love goddess. I will use a Victorian artist portraying a classical mythic scene to demonstrate that Not-For-Work-Safe pictures have been with us always, except that the classic nudes were more tastefully done, even beautiful:

The Birth of Venus by William Bouguereau

I am sure I can find a more family-friendly version:

Toon Aphrodite

A digression: I recall reading a complaint by an author whose name I will not repeat, that our modern society was not sufficiently sexual liberated and sexually active. As proof of our ongoing Puritanical repression, he offered the linguistic tidbit that while we have a word for 'virgin' we do not have a word for a woman who is not a virgin. I thought this a preposterous argument to make, because it betrayed the blind spot of the author making it. The word, of course, is wife.

Only the son of a deeply corrupt and unchaste society would overlook how the common wisdom of common culture celebrated the transition of the maiden into matron: with the symbolic tearing of the bridal veil, the change of a last name, and, in order and wiser days, with a change of hairstyle and dress and jewelry, particularly the wedding ring, to show that the woman was no longer a virgin.

Of course the sexual revolutionary had simply 'blanked-out' the existence of wives and mothers in his mind. His complaint was that there was no word for an unchaste unmarried women. To the contrary, there are many such words. Demimonde or paramour is the politest of the words we can use for such women in polite company. End of digression.

Are there other female archetypes we can draw upon from classical sources? Certainly.While not a member of the pantheon herself, Hecate the Queen of Darkness is a favorite among feminists and neopagans alike, provided they don't read Hesiod and discover what she was really like.

I am not sure this is actually an image of Hecate. It's close.

There is many, far too many women these days who follow the example and archetype of Hecate. I think they think it is empowering.

There is a particular feminine bitterness, a fear of loneliness and a hatred of betrayal, which is as strong as a man's fear of failure and humiliation, which drives a woman to brew poison rather than, as man might, sharpen a long dagger to hide beneath his cloak and lie in wait for his foe. The witch, being less powerful in combat than the brute or bully, must carry out her malice in a venomous way which has naturally become an archetype for that aspect of feminine nature.

But what of even more powerless women, or damsels in distress? Here we must look for mortals, and not goddesses, because no one has every heard of a powerless goddess.

Briseis, the slavegirl possessed by Achilles and taken by Agamemnon, the source of his famed wrath in Homer's famous poem, springs to mind. Fortunately, this image is forgotten in the far past, no longer popular, and there is no fangirls who dress as her and fanboys who dream daydreams about her. Such a relief!

I am not sure this is actually an image of Briseis

The classical example of a woman who outsmarts all her suitors, and perhaps even her husband, is Penelope, the most faithful and loyal wife of longsuffering Odysseus. Every widow uncertain if her husband is dead, or every woman wilier than her man falls into this archetype.

Penelope and Suitors by Waterhouse

In fact, an interest contrast is made with her cousin and fellow Queen, Clytemnestra. Here is an image of her emerging from murdering her husband in the bath with a two-headed axe. The motive for the murder was complex, as all motives in myths are, but the political ambition of Aegisthus, who was both Clytemnestra's lover and the King's cousin with a clearer legal claim to the throne than he, formed part of it. Another part was her husband's murder of Iphigenia, and also his infidelity with Cassandra, whom he owned as his concubine.

Clytemnestra by Collier

Helen of Troy, another cousin of Penelope, was even more famous, and even more disloyal, for thousand ships she launched with her face ended up slaughtering more men than one, and more years than ten.

Helen of Troy

The degree to which the Helen archetype overlaps with the Venus archetype I leave for others to debate, but I will point out that unlike Venus dallying with Mars behind the back of her husband Vulcan, Helen's role in her own abduction is more ambiguous, and Homer, at least, portrays her affection for Paris is minimal.

What is the point of posting all this pictures of all these women? Is it merely a gratuitous excuse to show images of cute dames on the Internet? Of course not! If that had been my purpose, I would have posted a completely gratuitous shot of a woman dressed as catwoman.

No, my point is that femininity is a real thing, not an arbitrary social convenience or convention, and not limited to Japanese all-girl j-pop bands. In the example above, some archetypes represent things men cannot do at all, roles they cannot fill, such as Vestal virgins and seductresses and mothers and witches, and some archetypes represent roles men fill much better than women and with much more zest, such as ax-murderer or soldier boy.

My argument, or, rather, my statement, since I don't think the point needs to be argued, is that even when women fill traditionally masculine roles, they tend to do it in an identifiably feminine way: a woman in command acts like a Queen, not like a King. Women murder for the sake of jealousy, as in the case of Clytemnestra, far more often than for the sake of money, and far more often her husband or child than a stranger.

As for the Martial Maidens so beloved of the moderns, and women in combat, it is significant to recall that women still act like women and men still act like men.

Since this is a point on a topic where most people get their opinions not through experience but through the propaganda organs of the mass media, allow me to quote Robert Bork:

The Israelis, Soviets, and Germans, when in desperate need of front-line troops, placed women in combat, but later barred them. Male troops forgot their tactical objectives in order to protect the women from harm of capture, knowing what the enemy would do to the female prisoners of war. This made combat units less effective and exposed the men to even greater risks.Our military seems quite aware of such dangers, but, because of the feminists, it would be politically dangerous to respond as the Israelis did by taking women out of harm's way. Instead, the American solution is to try to stifle the natural reactions of men. The Air Force, for example, established a mock prisoner of war camp to desensitize male recruits so they won't react like men when women prisoners scream under torture. There is a considerable anomaly here. The military is training men to be more sensitive to women in order to prevent sexual harassment and also training men to be insensitive to women being raped and sodomized or screaming under torture. It is impossible to believe the both efforts can succeed simultaneously.

I listed Military Maidens as a female archetype common to the classical and Biblical cultural memory because it is: Camilla and Deborah, Semiramis and Boadicea people history and literature. How commonly real women fill this role is a separate discussion. The witch is also an archetype, and witches are make-believe.

However, there is one type or image of womanhood which is not an archetype: and that is Snow White wielding a sword.

Snow White, Warrior Princess

This is not an image calculated to strike terror into the heart of a foe. Something of the basic falsehood, the play-pretense of it, necessarily shows through.

Everyone knows that the preferred weapon of women in combat, especially if she is in a skintight catsuit or a brass brassiere, is the whip.

The Preferred Weapon of Womankind

A Completely Gratuitous Shot of the Catwoman

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 18, 2012

On Unisexuality

In recent comments in this space, we were discussing the difference between masculine and feminine with a reader who, having been raised on the politically correct dogma of unisexualism, had never before encountered the idea that men and women are different, except in trivial or arbitrary ways, and certainly had never encountered the idea that these differences are highly desirable, whether arbitrary or not.

The doctrine of unisexuality is a by-product of the doctrine that all human interactions, particularly between the sexes, is a war between oppressor and oppressed, exploiter and victim, a condition of mutual recrimination and hatred, with no possible conciliation. Those who promote this doctrine to its logical extreme are forced to conclude that all differences between the sexes are a conspiracy of men to exploit and oppress women, and that the only path to liberation is to abolish insofar as possible all differences and marks of difference. For the radical feminist, any sign of femininity is akin to the yellow star worn by ghetto Jews, a brand of surrender to oppression.

As with all doctrines issuing from the cultural Marxism called PC, this one goes by a deceptive name.

It is called Feminism, as if it aided rather than demeaned and denatured and harmed females.

It calls its opposition Sexism, as if to admire the complimentary differences of the sexes were race-hatred applied to the opposite sex rather than applied to a race.

The true name for the doctrine is unisexuality: the theory that men should be feminine and women should be masculine in order that both be equal and therefore at both sexes be at peace.

In other words, the theory is that any difference between the sexes creates conflict and exploitation.

The true name of its opposition is Romance: the theory that men should be masculine so that life is charged with wonder and heroism and drama for women, and that women should be feminine, so that life should be filled with beauty and love and drama for men, in order that both have lust and infatuation and romance and friendship and ecstasy and divinity, and both be happy, and therefore at both sexes be at peace.

In other words, the theory is that treating women like short and weak dickless men with boobs leads to contempt and conflict and exploitation.

The two theories rest on opposite ideas of the cause of any conflict between the sexes.

The reader seems to be someone bewildered by this doctrine of unisexuality, isolated from mainstream thought, but not a feminist himself, since he actually discusses the topic and does not adopt the tone of grinding stupidity and self-satisfied self-deception which characterizes the demeanor of PC-niks.

As a visual aid to the discussion, allow me to introduce exhibit A, a scene from the 1990′s Disney film A GOOFY MOVIE. The is a fan dub of the voices, but for the purpose of our exhibition, it will serve.

Now, the question for any interested students of romance is this. Which one of these characters is masculine and which feminine?

Theoretically, since these are not only animated characters, they are anthropomorphs or humanized animals with doggy noses, it should be impossible to tell their sex, since they posses no real sexual characteristics. We do not see either one of them giving birth nor nursing, for example. I am using these as an example precisely because they posses gender without possessing a sex; that is, they possess social or ceremonial or symbolic sexual markers without possessing physical markers.

Second, was their any doubt in your mind, even for a split second, which was which?

Is there even the slightly question in your mind that the animators intend her to be the female anthropomorph in the scene?

Ergo all the clues your mind picked up where in the voice, demeanor, or costuming. One had long hair, a higher pitched voice, with long eyelashes adorning large eyes.

More to the point, despite the fact that Roxanne is the one making the introductory move, an aggressive role usually reserved to the male, at no point is she masculine or unfeminine.

Indeed, this is cutie pie femininity at its most saccharine. Even I, ardent pro-Romantic that I am, find this lovestruck teen puppy love scene of, well, puppies in love almost too sweet for my taste. But fear not! There is even a MORE sickly sweet form of purely sugary femininity at large in the world. The Japanese have made a special science of cutie pie girlishness, and have a special word for it: Kawaii.

Here is a sample. Brace yourselves.

Now, please note again, that none of these girls are nursing or giving birth. The clues that they are feminine (or, rather, hyper-feminine) are deliberately exaggerated by several factors. They are too young to wed (except in Alabama with parent's consent); they are dressed in bright yet soft colors with flowers in their hair, in costumes that might as well be "cosplay" costumes. Note how they hold their hands and make their gestures, again, with exaggerated delicacy and youthfulness, clapping and smiling, singing, dimpling their cheeks with their fingers, bubbling with enthusiasm.

There is no trace of sober, solemn gravity in these girls. They are not standing on their virginal dignity and freezing the hearts of men with the cold purity of their unsmiling glances. They are not acting like warlords or crowned kings or Supreme Court Justices.

Now, at this point, a unisexualist might say, "But wait! None of these behaviors or gestures are natural and spontaneous! All are artificial! Therefore all are a cruel attempt to exploit, enslave, humiliate women! It proves all men are rapists who hate women!"

Unfortunately, the leap of logic between saying "this is artifice" and saying "this is an enemy attack prompted by hatred" is wider than the grand canyon.

Contemplate the exaggeration of infantile characteristics: this girls are absurdly girlish. The unisexualist, analyzing everything in terms of a remorseless Darwinian struggle to extermination, would assume the evil rapist-patriarch-oppressor wishes his victims small and weak so that he might more easily conquer and ravish them. The romantic, analyzing things in terms of reality, recognizes that healthy men have a nature desire to protect women and children whose lives he innately recognizes as more vulnerable and therefore more precious than his own. The romance of being a superman who rescues a Lois Lane that otherwise would not notice you is also not far from the core of masculine thought.

Unisexualists want men to be weak and women to be strong for the same reason they want Nazis to be weak and Jews to be strong: only an equality of strength can suspend the Darwinian war of mutual extermination between male and female. The mere fact that there is no such war and never has been is something that cannot occur to the unisexualist.

The Romantic man wants men to be strong because it is heroic, and romantic women want men to be strong because it is sexy. No girl wants to swoon into the arm of a man who will drop her, or be carried off by a prince on a white stallion too physically unfit to pick her up and carry her off.

Let us introduce exhibit three, which include not only girls dressed in "kawaii" outfits with giant hearts on their bosoms, but also girls dressed a greasers from the 50′s, an era in America which was particularly romantic after the horror of world war were passed, and popular culture attempted to exaggerate masculine and feminine characteristics:

Sorry, no English subtitles here. However, I am pretty confident that it is a love song of some sort.

Note that the fight scenes still take place in the masculine role: the girl dressed like a greaser is still fighting for the girl dressed like a bobbysoxer. (Girl-on-guy violence is portrayed as cheek-pulling, not known to cause death on the battlefield.)

Note here that the girls when dressed as guy still look very girlish, as if dressing up as guy merely emphasizes that they are not guys. They are still cute, that is, cute enough attractive to the opposite sex, or, considering their young age, cute enough to bring out fatherly feeling of protectiveness and admiration in men.

But guys in drag look comical, i.e. not sexually attractive to women.

Unisexualists might simply deny this fact, since their whole philosophy and mindset rest on denying facts for their appeal. But supposing it were admitted, the unisexualist might say that girls-as-guys are judged differently from guys-as-girls because and only because of a cruel, foolish, and evil and arbitrary social value judgment intent on humiliating and exterminating gays and sissies, and therefore while the fact of the difference exists, the difference must be abolished in the name of social justice.

What the unisexualist cannot admit, lest the entire philosophy collapse, it is that females look for different sexual characteristics than males in selecting a mate.

Females are less shallow than men, and tend to think in the longer term: they want permanence. Whether there are evolutionary reasons for this based on the fact that men father children but women bear and nurse them, I leave for others to discuss: if it is evolutionary, it is an example of evolution following and reinforcing common sense.

Men are shallow. I use the term not in a derogatory way, but merely to point out that they tend to be sexually stimulated visually. They are looking for surface features. Common sense would tend to argue that seeking a mate able to bear children, and seeking to rear one's own child rather than fall victim to a Cuckoo, a father should seek youth and health and energy and zest in a woman, because child-rearing is exhausting, and a young woman is more likely to be a virgin, and a virgin cannot, absent supernatural intervention, bear another man's child as a changeling for your own.

Likewise, common sense would urge the woman to seek an older male with high rank and status, a good provider and protector, someone able to clothe and feed and shelter Mom and junior, as well as drive off wolves and predators, both (in ancient times) literal wolves, and (in modern) figurative. Hence, she should look for confidence, courage, aggressiveness, competence. She wants a winner.

The unisexualist might at this point shriek and whine and scream in outrage (they cannot discuss things in a normal tone of voice) but why, oh, why should the standards of what the two sexes find romantic be different! Now that dishwashers have been invented, and microwave ovens, women do not need to nurse, and in a welfare state, Uncle Sam will provide both paycheck and protection to the young mother! There is no need for men to be manly! In fact, manliness and aggression, causing wars and arguments, creates unhappiness and should be abolished!

Well, the only proper response to this argument is that it is false. Even a cursory examination of single-parent Moms raising multiple bastards sired of multiple live in boyfriends on public welfare shows the children have absurdly high chances of ending up in one self destructive behavior or another, from drug abuse to juvenile delinquency, the act of committing vandalism not for gain or for any rational reason, but only for the pleasure of destruction. The childmurder rate has climbed, since the number one cause of child murder is at the hands of a live-in boyfriend not the child's father.

A man does not need an aggressive show-offish macho woman to mother his children, only a fiercely loyal one. The characteristics being discussed here, cuteness and sweetness are signifiers of that loyalty. But a woman needs an aggressive macho man to drive away wolves, both the masher kind and the bill collector kind.

A girl dressed as a guy does not seem less cute and sweet to a guy; but a guy dressed as a girl does seem less macho to a girl.

Now to the main point: the unisexualist, forever terrified that the war where men try to enslave women in preparation to exterminating them will break out again, forever terrified of a completely imaginary therefore completely manageable danger (that is, a danger with none of the inconveniences of a real danger) are terrified that girls acting artificially girlish will trigger the apocalypse and a return of the Dark Age, that is, circa AD 1950, when women where bought and sold in public markets like cattle, and forced to fight each other to death in the gladiatorial arena with whips while dressed like catwoman in a skintight leather catsuit and nosebleed high heels.

Unisexualists do not want to see the return of the dystopia portrayed in A HANDMAID'S TALE by Margaret Atwood. That such a society never existed is fact that does not concern them: they are not concerned with fact, but with emotions, particularly hysterical emotions.

So that would argue that girls acting artificially girlish is a dangerous thing, and may trigger a sudden epidemic of rape and wifebeating. In order to avoid this danger, it is important to raise boys to think that girls are just as strong and aggressive as boys, to take girls off the pedestal and encourage boys to beat them as equals. The utter illogic of this is invisible to the unisexuals: they are a unconcerned with logic as they are with facts.

But the root problem is the role of artifice in human affairs. Here, unfortunately, the argument is so weak as not to exist. The Kawaii Japanese schoolgirls in these videos do not act like warlords or Supreme Court Justices or crowned kings, that is, with dignity and gravity.

But dignity and gravity is as artificial as girlish gaiety. Justices wear black robes; they do not show up naked in court. Kings wear crowns and sit on thrones and surround themselves with ceremony intended to impress subjects and enemies alike with his regal dignity and power. They also do not appear naked in public. The artifice is meant to exaggerate the natural characteristic.

Likewise with feminine modes of dress and speech and behavior. Indeed, the cleverness of using clothing to exaggerate sexual characteristics is that corsets and bras draw attention to the bosom of women, and high heels and skirts draw attention to their hips, because these are characteristics men lack. Women attempt to minimize drawing attention to their facial hair and armpit hair and leg hair, because they are less hairy than men naturally, and so will shave or pluck to emphasize or exaggerate that difference.

The unhidden secret of this all is that when, on her wedding night, the bridal veil is torn and her gown shucked off, and she presents herself in all her naked beauty to her bridegroom, those very parts she covered up, by the mere act of covering them up, made them more alluring than they would be in a world of nudists. The male likewise but to a lesser degree, since the female is less concerned with his physical looks than with his confidence and demeanor and strength.

Far from being a condemnation, that fact that these artifices are artificial proves that they are regarded (by everyone except for unisexuals) as necessary and proper to the pursuit of love.

Of course they are artificial. So are all tools. The reason why we use tools is because we are human. And it is that, our humanity, which at the root of all things is the enemy of the unisexuals and all their cousins.

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

Wolverton on the Limits of the Mainstream Genre

A simply fantastic (in each sense of the word) essay by Dave Wolverton. Here is the opening:

Rant Fantastic

"On Writing as a Fantasist"

by Dave Wolverton

I recently read in Tangent #17 James Gunn's response to a question by Cynthia Ward, who asked about the dichotomy between mainstream literary standards and those of science fiction and fantasy, and asked someone to "Name names."

I respect Gunn's work a great deal, but I disagreed with his response, partly because I began my writing career in the literary mainstream, made my first money in that field, and eventually came to recognize that fundamentally I disagreed with much of what was being done. There are differences between my approach to writing as a modern fantasist (who makes no apologies for being a commercial writer) and the approach taken by literary mainstream writers. The issues aren't trivial.

Cynthia asked what the earmarks are of a mainstream story, and Gunn responded by saying that its "distinguishing characteristic is that it has no distinguishing genre characteristic."

This is of course what my professors taught me in English Lit 101. And it is somewhat true. The Western genre is defined by its setting. The Romance and Mystery genres are defined by the types of conflict the tales will deal with. Speculative fiction may be defined by the fact that we as authors and fans typically agree that nothing like the story that we tell has ever happened–though one could well argue that speculative fiction isn't a "genre" in the classical sense anyway.

But I contend that over the past 120 years, and particularly in the last 20 years, the literary mainstream has evolved into a genre with its own earmarks. It is just as rigid in its strictures and just as narrow in its accepted treatment of characters, conflicts and themes as any other genre.

The postmodern literary establishment grew out of the philosophies of William Dean Howells (1837-1920), the "Father of Modern Realism," who was an editor for The Atlantic Monthly from 1866-1876.

He claimed that authors had gone astray by being imitators of one another rather than of nature. He proscribed writing about "interesting" characters–such as famous historical figures or creatures of myth. He decried exotic settings–places such as Rome or Pompeii, and he denounced tales that told of uncommon events. He praised stories that dealt with the everyday, where "nobody murders or debauches anybody else; there is no arson or pillage of any sort; there is no ghost, or a ravening beast, or a hair-breadth escape, or a shipwreck, or a monster of self-sacrifice, or a lady five thousand years old in the course of the whole story." He denounced tales with sexual innuendo. He said that instead he wanted to publish stories about the plight of the "common man," just living an ordinary existence. Because Howells was the editor of the largest and most powerful magazine of the time (and because of its fabulous payment rates, a short story sale to that magazine could support a writer for a year or two), his views had a tremendous influence on American writers.

But as a writer of fantastic literature, I immediately have to question Howells's dictates on a number of grounds.

Howells contended that good literature could only be written if we did three things: 1) Restrict the kinds of settings we deal with. 2) Restrict the kinds of characters we deal with. 3) Restrict the scope of conflicts we deal with.

Is it so? Can no "good" literature be written outside the scope of these dictates? More on that later.

Regardless of the lack of reasoning behind his dictates, Howells's dictums form the nucleus of what is being taught as "good" literature in mainstream college literature courses. These dictums also provide the framework for nearly all of what is published in the largest of the mainstream literary magazines–the New Yorker and the Atlantic Monthly, and in the smaller literary journals.

Now, the realists have been so hide-bound in their views about what constitutes great literature that the work of fantasists has generally been overlooked, if not actively rejected, for well over a hundred years.

For decades no novel of science fiction, fantasy, or horror was allowed to appear on the New York Times Bestseller list, regardless of how many copies such a novel actually sold. Thus in the early 1970s a work by Stephen King that sold a million copies in a month wouldn't even hit the list, while a book that sold fifty thousand copies held the number one position. Why? Because in New York, the work of fantasists wasn't considered literature. (The same can be said for other genres. Romance, Westerns, mysteries–all forms of "genre" literature were considered beneath mention.) The same holds true to a lesser extent today. No Star Wars novelization has hit number one on the New York Times Bestseller list despite the fact that such books often outsell three-to-one those novels that are listed as number one. I suspect that romances generally sell much better than the list-makers would like to admit.

For the same reason, the works of fantasists have been consistently passed over for literary awards and publication in the mainstream magazines. Regardless of how original the piece is, how moving, how insightful, how enervating [sic, he means exciting], or how beautiful, fantastic literature is considered incapable of being the equal of mainstream literature.

For this reason, it's difficult to find a university in the United States that teaches any kind of courses at all in fantastic literature (or any other genre), yet students must study realism for hundreds and thousands of hours. And in many –if not most– college writing classes across the country, students are forbidden to write fantastic literature at all.

But Howells's limiting dictates don't describe the worst aspects of the realist movement, which served as a precursor for our own postmodern mainstream.

The essay goes on to say:

Now, the realist and the postmodern movements had their good points, and if the movements were merely boring, I'd have no quarrel with them. But my real problem with the whole realist literary movement and its resulting postmodern spinoffs is that it was founded on lies.

William Dean Howells claimed to have been "tired" of reading fantastic literature. But how did he formulate the proscriptions that led him to define what "good" literature should be? Did he look at the best of existing literature and derive his proscriptions from that? Or through some vivid and overwhelming insight did he envision a more fertile literary landscape?

No. He did neither.

The truth is that Howells was a socialist, and he was trying to encourage–nay, dare I say bribe–other authors into writing propaganda for him. He wanted American writers to tackle economic issues, much as he did in his own fine work, The Rise of Silas Lapham, and it is significant that Howells's literary field attained full fruition in the works of the great socialist writer John Steinbeck.

Now, I don't have a bone to pick with the socialists. They deserve to have their own literature, just like anyone else. But Howells never did bother to put forward an objective argument when he attacked the fantastic in literature. He said that he valued literature that was true and honest, yet he himself was being dishonest.

Any nitwit can point out that literature does not have to show the world as it is in order to be true. Metaphor suffices. I believe that Howells never presented an objective argument because he knew that he was lying and that the finest literature the world has ever known has almost always been fantastic literature:

Shakespeare's best works–The Tempest, Hamlet, and Macbeth–feature exaggerated characters from poorly researched histories and are set in faraway lands. They feature ghosts and monsters and witches. They feature powerful characters in life-and-death conflicts. They feature everything that Howells decried.

Were they by any standard of Howells's day, or ours, bad? Boring? Weak? Inferior? What of Milton or Homer or Sophocles? Was their work in any way inferior to that of other writers of their day?

On what grounds?

What rational basis did Howells have for trying to limit the scope of our stories?

Why should we follow the fool now?

Howells didn't seek to understand how literature really worked; he tried instead to make it serve his political agenda.

And more! Read the rest here:

http://www.sff.net/people/dtruesdale/wolverton1.htp

Hat tip to Tom Simon

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 15, 2012

Memorable SF Characters of the Essential Authors

Mr Wizard writes:

"So much of science fiction is soulless from a human view. And a lot of the presumptions of even major works of science fiction are laughable. There is a lot of wow in science fiction, but they rarely reach me, rarely are remotely capable achieving catharsis. Usually I can remember nothing of any of the characters."

My comment: That SF is emotionally flat is a very common criticism of science fiction, and, unfortunately, an often merited one. Detective stories, particularly ones that concentrate on the intellectual process or police procedure of solving the crime, suffer a similar criticism.

But the sheer forgettability (not a word, but it should be) of most SF characters, particularly of early SF, is legendary. This is odd, because any competent editor will tell you that characters drive the story.

On the other hand, writers as different from each other as H.G. Wells and G.K. Chesterton point out the advantage of having a bland 'everyman' or 'anyman' as the hero of a wonder tale: the reader can place himself in the shoes of an everyman more easily than in some quirky or unique hero, and when the backdrop and props and plot are futuristic or fabulous and filled with spectacle and dazzle, a hero who pulls attention to himself is a distraction.

If the hero is as ordinary as Jack, the reader is aghast at how extraordinary is the giant, whether a titan from a fantasy tale, or a giant armored battle-station from a space opera.

I propose, however, a short survey of all science fiction from its origins to the present day, and an examination of how memorable the characters are, and how that has changed.

This being too great a task for one article, let me use a slight of hand instead, and only consider the characters depicted in the list I created for the 50 essential authors of science fiction. Now, this procedure is a little unfair, because it will not list memorable characters appearing in non-essential books, which perhaps include some of the most memorable characters ever. So keep that limitation in mind as we proceed.

http://www.scifiwright.com/2012/01/the-fifty-essential-authors-of-science-fiction/

Looking over my list of 50 essential authors to read to be SF fans, I notice a peculiar dearth of memorable characters. Some of these tales, I cannot even bring the names of the protagonists to mind.

Let me use a completely subjective standard of what is memorable, namely, do I think with my skills as a writer, or those of any other obscure midlist writer of ordinary skill, could portray the particular nuances of speech and mannerism which the character shows, and have him be recognized by the reader?

Could I identify two or more dreams or main motivations pulling the character in opposite directions? This last is the crucial question. One-dimensional characters have no motivation; two-dimensional characters have a simple motivation; three-dimensional characters, as in life, have conflicts of motivation.

There is a second thing that makes characters memorable: those with no particular details given about their lives are memorable if they are archetypes. Those with particular details are memorable if the details are organic to the character, not merely arbitrary quirks. Do I know the character well enough to anticipate his taste in women, food, sports, music, politics?

Of early science fiction, characterization was almost nonexistent.

Dr. Victor Van Frankenstein. He is torn between his normal life, his fiancée, and his ambition to play God, and the evils that come when he fathers a monster but does not love it, or raise it. The conflict in the character is the central fact of the character, and he is memorable enough to have created any entire trope of his own, if not a genre. All Mad Scientists and Mad Inventors are stepchildren of Dr Frankenstein.

Captain Nemo and Robur the Conqueror. These are the archetypal mad inventors of science fiction, but having slightly more personality than their many epigones. Unlike Frankenstein, it is pride which pushes these men of genius beyond the pale.

Impey Barbacane. A halt-at-nothing Yankee. The description of the gunnery club members, maimed and dismembered from their many dangerous experiments with gunpowder, fixed this archetype in mind. Had he been a bad guy, he would have been a mad inventor.

Of H.G. Wells characters, I am afraid the only ones I find memorable are the Martians, the Selenites, or Weena the Eloi and Morlocks. But even they are memorable only as static archetypes: the Martian is the archetypal "superior being" of Victorian Darwinism. As modern men were thought of as being more refined and intelligent yet weaker than the noble savages of the Cave-Man, the Martians are creatures of immense hands and brains, the evolutionary advantages of mankind extrapolated to absurdity, occupying artificial bodies of metal, fighting machines and handling machines.

Likewise, the Selenites are buglike socialists. The Eloi are weak and useless aristocrats extrapolated to absurdity, and the Morlocks brutal workingmen. The Wells characters do not lodge in the mind like a Charles Dickens' character. The Time Traveler does not even have a name.

Of the characters from A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS by David Lindsay, the protagonist Maskull is an everyman with no distinguishing features aside from his luck, his strength, and his audacity. The other characters are memorable for their allegorical or symbolic value, and I would say extravagantly or outrageously memorable: I have never read a character of more divine and sublime self-sacrifice and grace than Joiwind, or more noble than Panawe, or more outrageously sensual and crass than Oceaxe, cruller than Crimtyphon, or more austere than Spadevil, and so on. But, again, while sharply vivid, these are archetypes. Oddly enough, they are archetypes apparently from Lindsay's personal Gnostic mythos, so they are memorable to a degree because they are odd.

The books by Olaf Stabledon, LAST AND FIRST MEN or STARMAKER cannot be rated on their characters, simply because they have none. These are books of future history where whole eons are brushed past in a paragraph, so we are lucky if the races of man are memorable enough to be given personalities. I would, myself, say that they are: I can recall easily to mind the difference between the athletic biotechnicians of the Third Men, the Great Brains of the Fourth Men, the sane supremacy of the Fifth Men, the mystical Seventh Men and their wings, the pedestrian Eighth Men.

The dystopian novels of early British SF, NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR by George Orwell and A BRAVE NEW WORLD by Aldous Huxley, don't have any characters worth mentioning. Both John Savage and Winston Smith are everyman figures. Savage, being from a backward part of the globe, represents something more akin to the modern reader's viewpoint. The everyman is on stage to be awed or appalled by the shock of these dark futures.

Let us move onto the pulp era: we strike a new archetype here. Instead of merely mad scientists or awed or appalled everyman figures, the pulps held heroes. Edgar Rice Burroughs and E.E. 'Doc' Smith introduced us to clean-limbed fighting men of Virginia, or Gray Lensmen who were the peak and perfection of human prowess, and for superhumans somewhat nondescript.

Ironically, the most memorable SF character who stands out from the pulp era, to me, is Marc C "Blackie" DuQuesne, the arch-villain of the Skylark series, because his mental capabilities were equal to the goodguy superscientist, or fractionally inferior, but he was not a mad scientist, merely whose mind was as vast, cool and unsympathetic as that of the Martians of Wells.

E.E. Smith, however, in his Lensman series, pulled off a feat of characterization not to be equaled until Larry Niven, introducing not one but three utterly alien races, each with its own psychology and personality type, who lived up to the Campbellian challenge of showing readers an alien who thought as well as a man but not like a man: by which I mean Nedrick of Palain VII, Trigonsee of Rigel, and Worsel of Valentia. By human standards, these beings are pathologically cowardly, or bovine in their placidity, or manic-depressive in their battle-frenzy. The cleverness of the conceit here is that humans likewise, with our moral corruption and penchant for emotionalism, seem to these beings as mad as they seem to us.

I can list only two aliens from this early period of science fiction which strike me as comparably memorable: Tweel from 'A Martian Odyssey' by Stanley G. Weinbaum and The Mother from 'The Moon Era' by Jack Williamson. But, even so, I give the laurels to E.E. Smith, because his aliens have recognizable psychologies with understandable limitations. Tweel is merely odd.

As for characters from H.P. Lovecraft, I can barely recall a name aside from that of Randolf Carter, whereas his many aliens both extraterrestrial and ultradimensional — who may have indeed been gods or devils — I could rattle off like a fanboy, which, indeed I am.

One factor which makes the human characters not memorable in many of these SF works is that the aliens are so memorable. The author wants to emphasize the strangeness of the extraterrestrial in the background, and this means the human in the foreground should be the opposite of strange. When Klatuu lands in a flying saucer, he does not hide among circus freaks, costumed vigilantes or satanists escaped from a mental institution. In order for the story to work, it must be a typical suburban household he enters.

Another factor which tends toward the blandness of SF heroes, come from the tradition of 'golden age' SF under the editor John W. Campbell Jr., under the Big Three authors of Heinlein, Asimov, and Van Vogt. Namely, that these men quite conscientiously set out to make a certain type of approach to life, a certain type of man, appealing to the audience. They were glorifying the technically competent man, the engineer, the scientist.

In the same way that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle determined that his Great Detective Sherlock Holmes would be a man of ascetic intellectualism, as precise and unemotional as a theorem of Pythagoras, Campbell and the Big Three presented a view of man as a creature of reason, almost as a Houyhnhnm, who solves his problems with Sherlockian detachment.

And such men tend not to be quirky or self-aggrandizing. The most we can expect from them is a wry sense of humor.

Let me contrast this Golden Age archetype with John Carter, steely gray-eyed clean-limbed fighting man of Virginia and Warlord of Barsoom. Carter describes himself in the opening chapter in this way:

"I do not believe that I am made of the stuff which constitutes heroes, because, in all of the hundreds of instances that my voluntary acts have placed me face to face with death, I cannot recall a single one where any alternative step to that I took occurred to me until many hours later. My mind is evidently so constituted that I am subconsciously forced into the path of duty without recourse to tiresome mental processes. However that may be, I have never regretted that cowardice is not optional with me.

[...] whether I thought or acted first I do not know, but within an instant from the moment the scene broke upon my view I had whipped out my revolvers and was charging down upon the entire army of warriors, shooting rapidly, and whooping at the top of my lungs."

In other words, John Carter, coming suddenly by moonlight upon an entire armed camp of some five hundred ferocious Apache braves, instead of retreating or thinking of retreat, pulls a 'Rooster Cogburn' with guns in both fists and reins in teeth, and leads a one-man cavalry charge. Without, so he testifies, 'recourse to tiresome mental processes.'

John Carter is fundamentally a man of passion rather than a man of intellect. In one scene in A PRINCESS OF MARS, he deserts his post, and cuts down four guardsmen in the armed forces in which he himself has taken service. He voices only a momentary regret: "They were brave men and noble fighters, and it grieved me that I had been forced to kill them, but I would have willingly depopulated all Barsoom could I have reached the side of my Dejah Thoris in no other way." Lucky he was armed with a longsword rather than the Death Star. Important safety tip: do not get between John Carter of Virginia and the incomparable Deja Thoris of Helium.

No character in any tale by Heinlein, Asimov, and Van Vogt, to the best I can recollect, kills a single mook, either in open combat or ambuscade, while driven by unconquerable masculine passion for their true love.

Heinlein's protagonists tend all to be the single archetypal Heinlein character: the eager young boy who grows into a wry but all-competent jack-of-all-trades and eventually into a wry and crusty old man, usually marrying a lusty jill-of-all-trades nudist redhead somewhere along the way. Asimov's protagonists are much the same, but with less wryness and no redhead. Van Vogt's protagonists are much the same, but with no wryness at all, sometimes with amnesia, and he evolves into a superhuman rather than a crusty old man.

We can remember the personality-free personalities of Asimov's Robots, and the strangely un-Campbellian altruism and nobility of A.E. van Vogt's superhumans, Jommy Cross the Slan or Walter S. Delany the Immortal, and I think a number of van Vogt's monsters are memorable, the Coeurl, the Ezwal and the Rull.

And yet the blandness, the lack of any distinguishing personality characteristics, of most of these writers is almost astonishing. Perhaps the only memorable character in the entire canon of Asimov stories is Bayta Darell; perhaps the only memorable character in Heinlein is Podkayne of Mars.

Why should this be? The uncomfortably non-unisex fact of the matter is that in order to portray a female character, the writer must make her non-generic, such as Bayta who pities the Mule, or Podkayne who dreams of being a star-captain, and dies (or is severely wounded) while going back to save a pet.

(Feminists may wish to make women as bland and interchangeable and replaceable as males, but, alas, nature and evolution are against them. The default assumption is that males fight and female love, and the nature of reality is such that life and love is automatically more interesting than death and bloodshed. The female character, if she is feminine at all, automatically has an additional dimension and a depth of character males do not naturally display.)

If I may let slip a professional secret: when I had to portray A.E. van Vogt's amnesiac superhuman Gilbert Gosseyn in my own NULL-A CONTINUUM, I had to deduce something about his values and virtues, his preferences and personality on stage. Aside from being a trained Null-A, and espousing the values of that philosophy, what was their to him?

I took the hint dropped in chapter one of WORLD OF NULL-A which establishes that Gosseyn, before coming to the City of the Machine for the great games, had implanted the false memory of being a fruit farmer, and so I decided (or deduced) that Gosseyn must share a farmer's love of the soil, steady work and hard, and have a trace of a rural man's mistrust of big city folk and their ways.

But he has as little internal conflict over clashing goals as that other perfectly sane and rational science fiction superscientist, John Galt. There is a fine line between an archetypal character and a one-dimensional one. It was much easier to come up with a personality for Patricia Hardie or Enro the Red, since I could use personality types van Vogt had established in his other works.

But this is a roundabout way of admitted that, much as I admire the man's work, the superhumans of Van Vogt were simply not fully three-dimensional characters. Snatch up Captain Maltby of the Mixed Men and throw him into the situation of Jommy Cross, lost in Centropolis and hunted by the secret police; or snatch up Jommy Cross the Slan and place him in charge of the Weapon's Shops of Imperial Isher — would either character act or talk any differently than the one he is replacing?

In the Silver Age, at last, we start getting some characters who are at least two-dimensional or moreso. Nicholas van Rijn from Poul Anderson, Gully Foyle ("I kill you filthy, Vorga!") from Alfred Bester do not fit into any easy stereotype, and do not fade quickly from the memory.

I have a personal fondness for the characters of Keith Laumer, but I must admit they are, for the most part, pastiches of hard boiled detectives. The comedic super-diplomat Retief is memorable merely for the humor of his yarns.

Then we suddenly run into a rich stratum of characters who are fully developed with fully realized personalities: I will mention Sam from Zelazny's LORD OF LIGHT, or the complex and bitter Corwin of Amber, or the more complex and more bitter Elric of Melnibone, or Jim Nightshade and William Halloway from Bradbury's SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES, but I will give laurels to Glenly Ai, the Mobile of the Ekumen on Gethen, or to Therem Harth rem ir Estraven from LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS. Ursula K LeGuin was simply better at portraying human complexity in characters than any of her peers.

At about this same time, Cordwainer Smith burst on the science fiction scene, making a remarkable impact for a relatively small number of short stories, and, oddly enough, his protagonists were not heroes in the classical sense, but something much more rare and precious: human beings. No matter how odd their outward forms, scanners or underpeople, they had human souls. It is no coincidence that Smith sold his work outside of the circle of John W Campbell Jr.

At the same time, aliens started getting more complex portrayals: let me mention C.J. Cherryh's Chanur as an example. The Kzin and the Puppeteers of Larry Niven's Known Space stories parallel the warlike nature of the Valentians and the cowardice of the Palainians as seen in the Lensmen series.

In cyberpunk stories we then come across a stratum of characters so vivid and fully realized that some of them droop over into the territory of anti-heroes, which unfortunately makes them a bit un-memorable again. It may just be my advancing age, but I cannot recall the names of any characters penned by Walter Gibson or Bruce Sterling. Neal Stephenson rather amusingly named his hero protagonist Hiro Protagonist, and made him a pizza-delivery samurai.

At about this same time, complexity and moral ambiguity make a terrific impact on the characters in that brother genre of science fiction, superhero comics: Alan Moore's THE WATCHMAN was a graphic novel in the true sense of the word, a novel as complex and rich as anything on the printed page, but told by means of illustrated panels.

Of all the authors listed as 'essential' I must award the most fully realized characters, the most realistic, human, and at the same time strange in the way only humans can be, to Gene Wolfe. No one has ever displayed a more masterful command of character's voice. No character is simple, and none easily forgotten.

I will mention only a few: Severian the Torturer, who is exiled for the crime of pity, and haunted by a stolen relict from a higher universe; and Horn, who seeks across a vampire-infest world for a man who may or may not be himself, hating his own son yet loving his son's unnatural impersonator; Patera Silk, perhaps the only convincing portrait of an extraordinarily good man I have ever write in any genre; and a convincing portrait of the extraordinarily unrepentant Bax Dun, the sorcerer in the empty house in a small town. Like the house itself, he is not what he seems, and is bigger on the inside than out.

As of the modern day, I would say the science fiction has shed its need for simplistic and un-memorable protagonists. Science fiction is the mainstream.

View or comment on this post at John C. Wright's Journal.

March 14, 2012

John C. Wright's Patented One Session Lesson in the Mechanics of Fiction

Note: this is a reprint of an article I wrote in January of 2011. I reprint it here as a companion to my previous article on how to get published.

Here is the John C. Wright patented one-session lesson in the mechanics of how to write fiction.

A word of explanation:

I wrote the following to a friend of mine who is a nonfiction writer of some fame and accomplishment, who was toying with the idea of writing fiction. We batted around some ideas and I have been encouraging (read: pestering) him to take up the project seriously.

He wrote back and said that while putting the logical format to a work of nonfiction was clear enough, he was not big on this artistic and poetical stuff. I took it upon myself to show him the logic behind the stuff that dreams are made of.

So here is what I wrote to provoke him to write, and I share it with any and all comers who wish alike to be writers.

For my part, I am eager to share my trade secrets. I do not fear competition. Unlike every other field, my value as a writer goes up, not down, the more competition I have: because more science fiction writers means more science fiction readers, a larger field, and more money in the field.

So I think everyone should try their hand at writing. I cannot read my own work for pleasure, after all.

* * *

Let me try to encourage you. First, get that book I recommended, WRITING THE BREAKOUT NOVEL by Maass. Second, actually set aside time to write your novel, time when you are not allowed to do anything else or find any other distractions. Sit and stare at the blank page for four hours. The tedium will either break your brain or break open any writers block.

I am so totally not kidding: if you want to learn Kung Fu, you must learn to break bricks with your head. If you want to be a fiction writer, you must learn to stare at a blank page with nothing but your name on the top without flinching, without weeping, without getting up to get a beer to fortify your faltering courage.

How it is done? How does one fill in the horrid pallid blankness of the blank paper, as monstrous as the whiteness of the White Whale sought by Ahab? Good question. There is a craft to it, a certain mechanics.

Let us take an example of a hypothetical first chapter of a hypothetical book. Let us pretend the book is called OLD MEN SHALL DREAM DREAMS.

CHAPTER ONE: THE NIGHTMARE OF NOTTING HILLAt first, I thought he was carrying the corpse of a child.

My professor of Applied Military Theology, Colonel MacNab came walking slowly into my little room in southeast London, the little oblong box on his back, and a cold and grim look on his features. I stood up and pulled off my cap, and MacNab scowled. "Not to worry. Its not human. We think. Clear a space and give us hand, there's a good lad."

It was dark except for the moon, and the streets below had been cleared of traffic. The only noise from outside was the clatter of an antiaircraft gun being pulled by a team of horses up the lane to toward the churchyard, and the swearing of the teamster.