Paul van Yperen's Blog, page 254

November 6, 2018

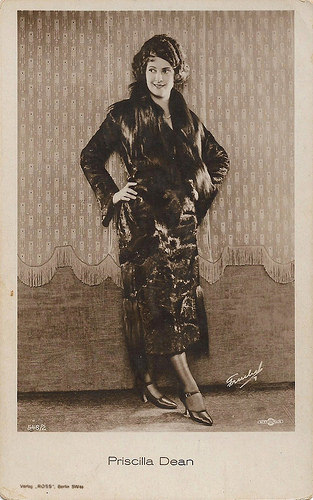

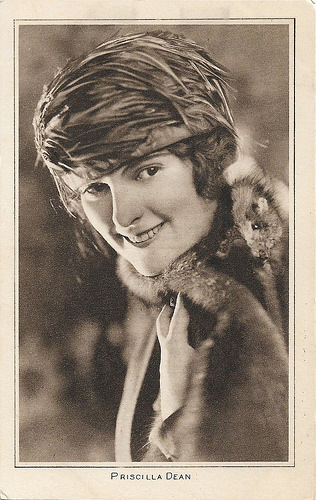

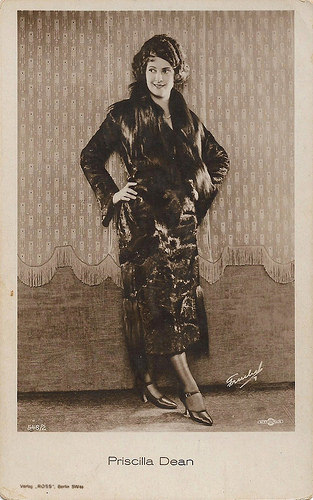

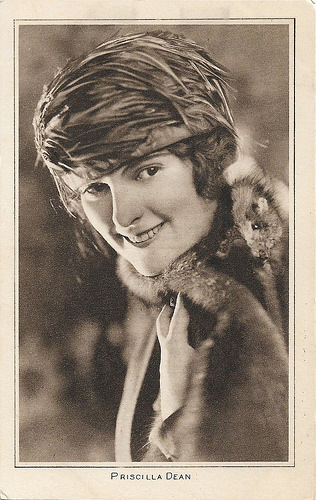

Priscilla Dean

Priscilla Dean (1896-1987) was an American actress of the silent screen. Between 1912 and 1928, she appeared in some 70 silent films, and later in five sound films. She is best known for her Universal films under the direction of horror specialist Tod Browning.

French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 3. Photo: Universal Film.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 548/1, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 548/2, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

David Wark Griffith

Priscilla Dean was born in 1896 in New York City as the daughter of theatre actors. Her mother was popular stage actress May Preston Dean.

From when she was four, Priscilla played in her parents' productions. As a child, she pursued a stage career at the same time as being educated at a convent school until the age of fourteen. By age 10, she was a seasoned professional.

Dean made her film debut and appeared in two short films, released in 1912. One of them was directed by D. W. Griffith for the Biograph company, A Blot under 'Scutcheon (1912).

Until 1928, she contributed to 68 American silent films, including many short films directed by Jack Dillon made in the mid-1910s for the Vogue Company.

From 1916 onwards, she worked for IMP, which was later merged with other film companies into Universal. She played the female lead in the Eddie Lyons & Lee Moran comedies, directed by Louis Chaudet for Nestor, another company which was merged into Universal.

In 1917 she acted in films by Lois Weber such as Even As You and I (1917) and The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1917).

Her appearance in the action serial The Gray Ghost (Stuart Paton, 1917) opposite Eddie Polo propelled her to stardom, and she began appearing in many of Universal's most prestigious productions.

Greta de Groat at Unsung Divas : "Priscilla Dean was a very unlikely diva. Her photos show a plain but cheerful looking woman, with rather heavy features, a crooked grin, and an unfashionably curvaceous figure. But on screen her intensity is unmatched. "

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 548/3, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 549/1, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 549/3, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

Tod Browning

Priscilla Dean is best known for her participation, between 1918 and 1923, in nine Universal films by Tod Browning. These films include The Wicked Darling (1919) in which she played a s pair of pickpockets with Lon Chaney , The Virgin of Stamboul (1920) with Wallace Beery, Outside the Law (1920), with Lon Chaney , Under Two Flags (1922), and White Tiger (1923), with Raymond Griffith.

Browning unleashed her talent. Her performance in Outside the Law (1920) is "startlingly fierce", according to Greta de Groat. In the French Foreign Legion melodrama Under two Flags (1922) she played Cigarette, a role re-created in a sound version by Claudette Colbert.

In The Virgin of Stamboul and Outside the Law, Dean played together with Wheeler Oakman, who was also under contract at Universal an was for a time her husband.

After 1923, Dean worked for several companies: she did quite a few films at Metropolitan, a few shorts at Hal Roach such as Slipping Wives (Fred Guiol, 1927), with Laurel & Hardy , and one or two productions at Hunt Stromberg and Columbia.

The coming of sound damaged her career. By the early 1930s she was appearing in low-budget films for small independent studios. Dean retired permanently from the screen after five talking pictures (three shorts in 1931 and two feature films in 1932).

Her last film was Klondike (Phil Rosen, 1932) with Thelma Todd and Lyle Talbot. Great de Groat: "Her starring career was brief, but there was nobody else quite like her."

Priscilla Dean was first married to Wheeler Oakman but they divorced in the mid-1920s. In 1928, she married Leslie Arnold in Mexico. Arnold was divorced, but one court called this invalid, making him a bigamist, but in the end that verdict was overruled.

Lt. Leslie Arnold had made history by flying around the world in 1924. Dean and Arnold remained married until his death in the 1960s. They had no children.

In 1987, Priscilla Dean died at her home in Leonia, New Jersey, after the complications of a fall one year earlier. She was 91.

British postcard.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 518/2, 1919-1924. Photo: Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1473/1, 1927-1928. Photo: Walter F. Seely, Los Angeles / P.D.C.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 88.

Sources: Greta de Groat (Unsung Divas), Michael Barson (Encyclopaedia Britannica), Silent Hollywood, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia (Italian and English) and .

French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 3. Photo: Universal Film.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 548/1, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 548/2, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

David Wark Griffith

Priscilla Dean was born in 1896 in New York City as the daughter of theatre actors. Her mother was popular stage actress May Preston Dean.

From when she was four, Priscilla played in her parents' productions. As a child, she pursued a stage career at the same time as being educated at a convent school until the age of fourteen. By age 10, she was a seasoned professional.

Dean made her film debut and appeared in two short films, released in 1912. One of them was directed by D. W. Griffith for the Biograph company, A Blot under 'Scutcheon (1912).

Until 1928, she contributed to 68 American silent films, including many short films directed by Jack Dillon made in the mid-1910s for the Vogue Company.

From 1916 onwards, she worked for IMP, which was later merged with other film companies into Universal. She played the female lead in the Eddie Lyons & Lee Moran comedies, directed by Louis Chaudet for Nestor, another company which was merged into Universal.

In 1917 she acted in films by Lois Weber such as Even As You and I (1917) and The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1917).

Her appearance in the action serial The Gray Ghost (Stuart Paton, 1917) opposite Eddie Polo propelled her to stardom, and she began appearing in many of Universal's most prestigious productions.

Greta de Groat at Unsung Divas : "Priscilla Dean was a very unlikely diva. Her photos show a plain but cheerful looking woman, with rather heavy features, a crooked grin, and an unfashionably curvaceous figure. But on screen her intensity is unmatched. "

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 548/3, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 549/1, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 549/3, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman.

Tod Browning

Priscilla Dean is best known for her participation, between 1918 and 1923, in nine Universal films by Tod Browning. These films include The Wicked Darling (1919) in which she played a s pair of pickpockets with Lon Chaney , The Virgin of Stamboul (1920) with Wallace Beery, Outside the Law (1920), with Lon Chaney , Under Two Flags (1922), and White Tiger (1923), with Raymond Griffith.

Browning unleashed her talent. Her performance in Outside the Law (1920) is "startlingly fierce", according to Greta de Groat. In the French Foreign Legion melodrama Under two Flags (1922) she played Cigarette, a role re-created in a sound version by Claudette Colbert.

In The Virgin of Stamboul and Outside the Law, Dean played together with Wheeler Oakman, who was also under contract at Universal an was for a time her husband.

After 1923, Dean worked for several companies: she did quite a few films at Metropolitan, a few shorts at Hal Roach such as Slipping Wives (Fred Guiol, 1927), with Laurel & Hardy , and one or two productions at Hunt Stromberg and Columbia.

The coming of sound damaged her career. By the early 1930s she was appearing in low-budget films for small independent studios. Dean retired permanently from the screen after five talking pictures (three shorts in 1931 and two feature films in 1932).

Her last film was Klondike (Phil Rosen, 1932) with Thelma Todd and Lyle Talbot. Great de Groat: "Her starring career was brief, but there was nobody else quite like her."

Priscilla Dean was first married to Wheeler Oakman but they divorced in the mid-1920s. In 1928, she married Leslie Arnold in Mexico. Arnold was divorced, but one court called this invalid, making him a bigamist, but in the end that verdict was overruled.

Lt. Leslie Arnold had made history by flying around the world in 1924. Dean and Arnold remained married until his death in the 1960s. They had no children.

In 1987, Priscilla Dean died at her home in Leonia, New Jersey, after the complications of a fall one year earlier. She was 91.

British postcard.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 518/2, 1919-1924. Photo: Unfilman.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1473/1, 1927-1928. Photo: Walter F. Seely, Los Angeles / P.D.C.

French postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 88.

Sources: Greta de Groat (Unsung Divas), Michael Barson (Encyclopaedia Britannica), Silent Hollywood, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia (Italian and English) and .

Published on November 06, 2018 22:00

November 5, 2018

American Vedettes, Part 2

On 28 October 2017, EFSP published our first selection from the French series Les Vedettes de Cinéma. The series was published in the 1920s by A.N. (Armand Noyer), located at Boulevard de Strasbourg in Paris. Then we focused on European stars, now on Hollywood stars. Yesterday we did a post on the male American stars, today we present 15 female stars of silent Hollywood.

Gladys Walton. French postcard by A.N., Paris in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 2. Photo: Universal.

Baby Peggy . French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 4. Photo: Universal.

Constance Talmadge. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 12. Photo: B. Frank Puffer / First National Location.

Norma Talmadge. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 14. Photo: F.N. - Location (First National).

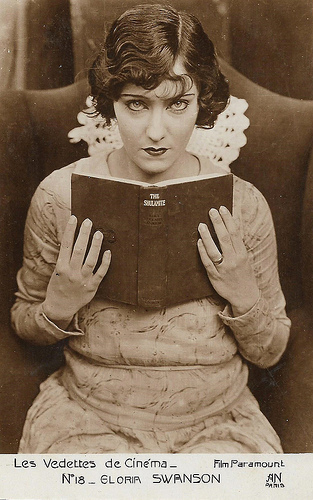

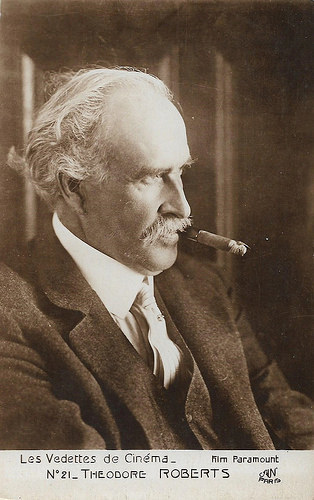

Gloria Swanson . French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 18. Photo: Paramount.

Lois Wilson. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 25. Photo: Paramount.

Betty Compson. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 30. Photo: Paramount.

Wanda Hawley. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 35. Photo: Paramount.

Lila Lee. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 38. Photo: Paramount.

Mary Miles Minter. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 40. Photo: Paramount.

Pearl White. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 55.

Judy King. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 199. Photo: Albert Witzel / Fox.

Margaret Livingston. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 204. Photo: Albert Witzel / Fox.

Gertrud Olmstead. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 207. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Claire Windsor. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 214. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

November and December will be EFSP's Hollywood months with European postcards of American film stars and films. From the 1920s, the Hollywood studios had their own photo departments, so we will stop with our series on photographers and start a new series on the Hollywood studios. It starts next Saturday, 10 November, with Warner Bros.

Gladys Walton. French postcard by A.N., Paris in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 2. Photo: Universal.

Baby Peggy . French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 4. Photo: Universal.

Constance Talmadge. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 12. Photo: B. Frank Puffer / First National Location.

Norma Talmadge. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 14. Photo: F.N. - Location (First National).

Gloria Swanson . French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 18. Photo: Paramount.

Lois Wilson. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 25. Photo: Paramount.

Betty Compson. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 30. Photo: Paramount.

Wanda Hawley. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 35. Photo: Paramount.

Lila Lee. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 38. Photo: Paramount.

Mary Miles Minter. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 40. Photo: Paramount.

Pearl White. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 55.

Judy King. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 199. Photo: Albert Witzel / Fox.

Margaret Livingston. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 204. Photo: Albert Witzel / Fox.

Gertrud Olmstead. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 207. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Claire Windsor. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 214. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

November and December will be EFSP's Hollywood months with European postcards of American film stars and films. From the 1920s, the Hollywood studios had their own photo departments, so we will stop with our series on photographers and start a new series on the Hollywood studios. It starts next Saturday, 10 November, with Warner Bros.

Published on November 05, 2018 22:00

November 4, 2018

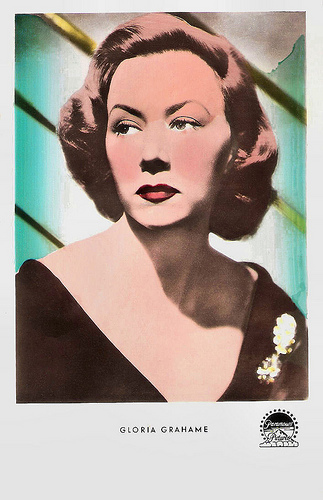

American Vedettes, Part 1

Before World War I, the European film industry ruled the world. The war destroyed the French studios and Hollywood started its victory in the international cinemas. And audiences all over the world simply loved the American movies, even in France. They adored the new American 'vedettes', as a popular series of film star postcards by Paris publisher A.N. (A. Noyer) shows: Les Vedettes de Cinéma. The postcards were published in the 1920s and today EFSP presents 14 postcards of the series with Hollywood men. The ladies will follow tomorrow.

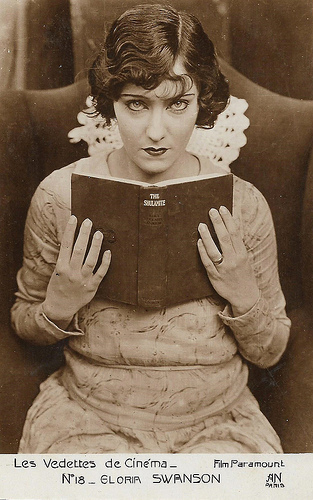

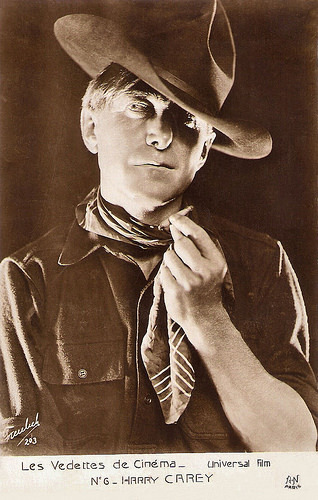

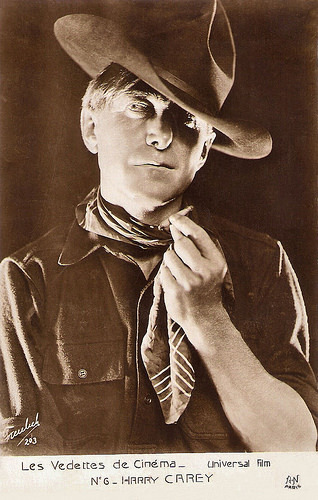

Harry Carey. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 6. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal.

Douglas MacLean. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 17. Photo: Paramount.

Walter Hiers. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 19. Photo: Paramount.

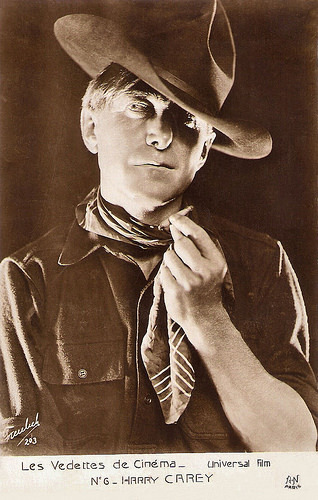

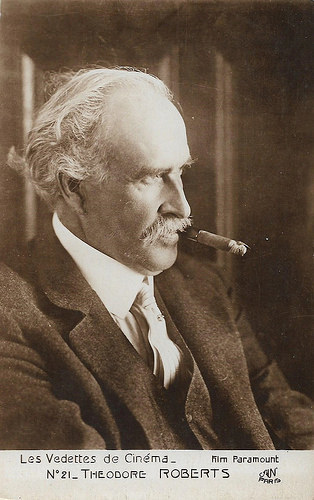

Theodore Roberts. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 21. Photo: Paramount.

Thomas Meighan and his children. French postcard by A.N. Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 21. Photo: Paramount.

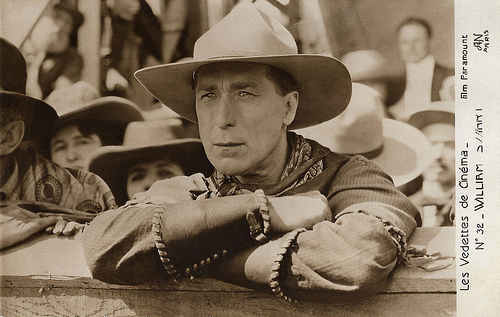

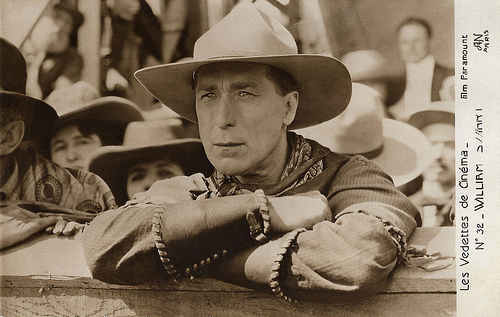

William Hart. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 32. Photo: Film Paramount.

Sessue Hayakawa . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 58.

Douglas Fairbanks junior . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 71. Photo: Paramount.

Charlie Chaplin , Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 85. Photo: United Artists.

Jackie Coogan on board of SS Leviathan in 1924. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 88. Photo: Rol.

Edmund Lowe. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 190. Photo: Fox.

Antonio Moreno. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 220. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Ramon Novarro . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 229. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Conway Tearle. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 230. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Rudolph Valentino . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 244. Photo: United Artists. Publicity still for The Son of the Sheik (George Fitzmaurice, 1926).

To be continued.

See here our earlier post on A.N., Paris .

Harry Carey. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 6. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal.

Douglas MacLean. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 17. Photo: Paramount.

Walter Hiers. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 19. Photo: Paramount.

Theodore Roberts. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 21. Photo: Paramount.

Thomas Meighan and his children. French postcard by A.N. Paris, in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, no. 21. Photo: Paramount.

William Hart. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 32. Photo: Film Paramount.

Sessue Hayakawa . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 58.

Douglas Fairbanks junior . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 71. Photo: Paramount.

Charlie Chaplin , Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 85. Photo: United Artists.

Jackie Coogan on board of SS Leviathan in 1924. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 88. Photo: Rol.

Edmund Lowe. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 190. Photo: Fox.

Antonio Moreno. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 220. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Ramon Novarro . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 229. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Conway Tearle. French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 230. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn Production.

Rudolph Valentino . French postcard by A.N. in the Les Vedettes de Cinéma series, Paris, no. 244. Photo: United Artists. Publicity still for The Son of the Sheik (George Fitzmaurice, 1926).

To be continued.

See here our earlier post on A.N., Paris .

Published on November 04, 2018 22:00

November 3, 2018

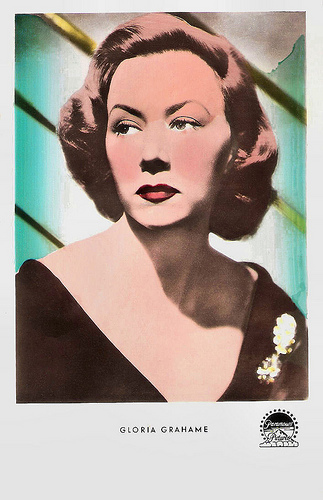

Gloria Grahame

American stage, film, television actress and singer Gloria Grahame (1923-1981) was often cast in Film Noirs as a tarnished beauty with an irresistible sexual allure. She received an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress nomination for Crossfire (1947), and would later win the award for The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Her best known films are Sudden Fear (1952), Human Desire (1953), The Big Heat (1953), and Oklahoma! (1955), but her film career began to wane soon afterwards.

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 1190. Photo: Universal International. Publicity still for Naked Alibi (Jerry Hopper, 1954).

A Tart with a Heart

Gloria Grahame Hallward was born in in Los Angeles, California in 1921. Her father, Reginald Michael Bloxam Hallward, was an architect and author; her mother, Jeanne McDougall, who used the stage name Jean Grahame, was a British stage actress and acting teacher. Her older sister, Joy Hallward became an actress who married John Mitchum, the younger brother of Robert Mitchum .

During Gloria's childhood and adolescence, her mother taught her acting. Grahame attended Hollywood High School before dropping out to pursue acting. She was signed to a contract with MGM Studios under her professional name after Louis B. Mayer saw her performing on Broadway.

Grahame made her film debut as a tart-with-a-heart in the sex comedy Blonde Fever (Richard Whorf, 1944) with Philip Dorn , and then scored one of her most widely praised roles as the flirtatious Violet Bick, saved from disgrace by James Stewart in It's a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1946). MGM was not able to develop her potential as a star and her contract was sold to RKO Studios in 1947.

She was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in Crossfire (Edward Dmytryk, 1947), a Film Noir which deals with the theme of anti-Semitism. During this time, she made films for several Hollywood studios. For Columbia Pictures, Grahame starred with Humphrey Bogart in another Film Noir, In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1950), a performance for which she again gained praise.

In 1952, Grahame starred in four major Hollywood-productions, including a part in the Film Noir Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952), starring Joan Crawford, and a reunion with James Stewart in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1953.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 791. Photo: RKO. Publicity still for Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952).

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 032. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane, 1953).

The Mysterious Bad Girl of Film Noir

29-year-old Gloria Grahame was on the verge of superstardom, when she herself won the Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance in The Bad and the Beautiful (Vincente Minnelli, 1952), starring Lana Turner and Kirk Douglas .

Sadly, following her Oscar victory, the beauty Grahame embodied so artfully on screen never reflected the personal turmoil festering under the surface. Her two marriages had ended in a divorce: one from allegedly abusive actor Stanley Clements (1945-1948), the other from Rebel Without a Cause director Nicholas Ray (1948-1952), with whom she had a son, Timothy.

In the following years, her image hardened as the mysterious bad girl of Film Noir in The Big Heat (Fritz Lang, 1953) and Human Desire (Fritz Lang, 1954). In a classic, horrifying off-screen scene in The Big Heat, her character, mob moll Debby Marsh is scarred by hot coffee thrown in her face by Lee Marvin's character.

In 1954, she acted and sang in the adaptation of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s musical Oklahoma! (Fred Zinnemann, 1955) as the 'girl who can’t say no,' Ado Annie. That same year she married writer-producer Cy Howard. After Oklahoma!, Grahame scaled back her work. There were rumours that she had been difficult to work with on the set of Oklahoma!.

Two years later, she divorced Howard. In 1960, she married former stepson Tony Ray, son of Nicholas Ray. This led Nicholas Ray and Cy Howard to each sue for custody of each's child by Grahame, putting gossip columnists and scandal sheets into overdrive. Rumours circulated that Grahame had initially seduced Tony when he was just 13. Along with her tarnished professional reputation, this gossip made her a Hollywood outcast.

Dutch postcard.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. D 7. Photo: Paramount.

A nervous breakdown and electroshock therapy

In the 1960s, Gloria Grahame dedicated herself to raising her growing family after having two sons with Tony. The stress of the scandal, her waning career and her custody battle with Howard took its toll on Grahame and she had a nervous breakdown. She later underwent electroshock therapy in 1964.

After that, she began a slow return to the theatre. She popped up as an occasional guest on TV series, and when she found her way back to the big screen, it was in exploitation films like Blood and Lace (Philip S. Gilbert, 1971) and Mama’s Dirty Girls (John Hayes, 1974).

In March, 1974, Grahame was diagnosed with breast cancer. She underwent radiation treatment, changed her diet, stopped smoking and drinking alcohol, and also sought homoeopathic remedies. In less than a year the cancer went into remission. Grahame never reclaimed her former glory, but the Oscar itself stood proudly on her mantel, an enduring reminder of her accomplishments.

In 1978, she met aspiring actor Peter Turner, while she was in Britain working on a stage production of W. Somerset Maugham’s Rain. Although Turner was nearly three decades her junior, they had a whirlwind romance. She co-starred in the British heist film A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square (Ralph Thomas, 1979) starring Richard Jordan, Oliver Tobias , and David Niven .

In 1980 followed her last major film, Melvin and Howard, (Jonathan Demme, 1980), in which she played Mary Steenburgen’s mother. The cancer returned in 1980 but Grahame refused to acknowledge her diagnosis or seek radiation treatment. Despite her failing health, Grahame continued working in stage productions in the United States and the United Kingdom.

At age 57, Gloria Grahame died in 1981 in a New York hospital from cancer-related complications. Peter Turner wrote about their love story in his memoir, Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool, which director Paul McGuigan adapted in 2017 into an excellent film starring Annette Bening and Jamie Bell.

Trailer The Big Heat (1953). Source: Chloroform and Silver Nitrate (YouTube).

Trailer Film Stars Don't Die in Liverpool (2017). Source: El Proyector MX (YouTube).

Sources: Joey Nolfi (Entertainment Weekly), Wikipedia and .

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano, no. 1190. Photo: Universal International. Publicity still for Naked Alibi (Jerry Hopper, 1954).

A Tart with a Heart

Gloria Grahame Hallward was born in in Los Angeles, California in 1921. Her father, Reginald Michael Bloxam Hallward, was an architect and author; her mother, Jeanne McDougall, who used the stage name Jean Grahame, was a British stage actress and acting teacher. Her older sister, Joy Hallward became an actress who married John Mitchum, the younger brother of Robert Mitchum .

During Gloria's childhood and adolescence, her mother taught her acting. Grahame attended Hollywood High School before dropping out to pursue acting. She was signed to a contract with MGM Studios under her professional name after Louis B. Mayer saw her performing on Broadway.

Grahame made her film debut as a tart-with-a-heart in the sex comedy Blonde Fever (Richard Whorf, 1944) with Philip Dorn , and then scored one of her most widely praised roles as the flirtatious Violet Bick, saved from disgrace by James Stewart in It's a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1946). MGM was not able to develop her potential as a star and her contract was sold to RKO Studios in 1947.

She was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in Crossfire (Edward Dmytryk, 1947), a Film Noir which deals with the theme of anti-Semitism. During this time, she made films for several Hollywood studios. For Columbia Pictures, Grahame starred with Humphrey Bogart in another Film Noir, In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1950), a performance for which she again gained praise.

In 1952, Grahame starred in four major Hollywood-productions, including a part in the Film Noir Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952), starring Joan Crawford, and a reunion with James Stewart in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1953.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. A 791. Photo: RKO. Publicity still for Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952).

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 032. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane, 1953).

The Mysterious Bad Girl of Film Noir

29-year-old Gloria Grahame was on the verge of superstardom, when she herself won the Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance in The Bad and the Beautiful (Vincente Minnelli, 1952), starring Lana Turner and Kirk Douglas .

Sadly, following her Oscar victory, the beauty Grahame embodied so artfully on screen never reflected the personal turmoil festering under the surface. Her two marriages had ended in a divorce: one from allegedly abusive actor Stanley Clements (1945-1948), the other from Rebel Without a Cause director Nicholas Ray (1948-1952), with whom she had a son, Timothy.

In the following years, her image hardened as the mysterious bad girl of Film Noir in The Big Heat (Fritz Lang, 1953) and Human Desire (Fritz Lang, 1954). In a classic, horrifying off-screen scene in The Big Heat, her character, mob moll Debby Marsh is scarred by hot coffee thrown in her face by Lee Marvin's character.

In 1954, she acted and sang in the adaptation of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s musical Oklahoma! (Fred Zinnemann, 1955) as the 'girl who can’t say no,' Ado Annie. That same year she married writer-producer Cy Howard. After Oklahoma!, Grahame scaled back her work. There were rumours that she had been difficult to work with on the set of Oklahoma!.

Two years later, she divorced Howard. In 1960, she married former stepson Tony Ray, son of Nicholas Ray. This led Nicholas Ray and Cy Howard to each sue for custody of each's child by Grahame, putting gossip columnists and scandal sheets into overdrive. Rumours circulated that Grahame had initially seduced Tony when he was just 13. Along with her tarnished professional reputation, this gossip made her a Hollywood outcast.

Dutch postcard.

German postcard by Kunst und Bild, Berlin, no. D 7. Photo: Paramount.

A nervous breakdown and electroshock therapy

In the 1960s, Gloria Grahame dedicated herself to raising her growing family after having two sons with Tony. The stress of the scandal, her waning career and her custody battle with Howard took its toll on Grahame and she had a nervous breakdown. She later underwent electroshock therapy in 1964.

After that, she began a slow return to the theatre. She popped up as an occasional guest on TV series, and when she found her way back to the big screen, it was in exploitation films like Blood and Lace (Philip S. Gilbert, 1971) and Mama’s Dirty Girls (John Hayes, 1974).

In March, 1974, Grahame was diagnosed with breast cancer. She underwent radiation treatment, changed her diet, stopped smoking and drinking alcohol, and also sought homoeopathic remedies. In less than a year the cancer went into remission. Grahame never reclaimed her former glory, but the Oscar itself stood proudly on her mantel, an enduring reminder of her accomplishments.

In 1978, she met aspiring actor Peter Turner, while she was in Britain working on a stage production of W. Somerset Maugham’s Rain. Although Turner was nearly three decades her junior, they had a whirlwind romance. She co-starred in the British heist film A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square (Ralph Thomas, 1979) starring Richard Jordan, Oliver Tobias , and David Niven .

In 1980 followed her last major film, Melvin and Howard, (Jonathan Demme, 1980), in which she played Mary Steenburgen’s mother. The cancer returned in 1980 but Grahame refused to acknowledge her diagnosis or seek radiation treatment. Despite her failing health, Grahame continued working in stage productions in the United States and the United Kingdom.

At age 57, Gloria Grahame died in 1981 in a New York hospital from cancer-related complications. Peter Turner wrote about their love story in his memoir, Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool, which director Paul McGuigan adapted in 2017 into an excellent film starring Annette Bening and Jamie Bell.

Trailer The Big Heat (1953). Source: Chloroform and Silver Nitrate (YouTube).

Trailer Film Stars Don't Die in Liverpool (2017). Source: El Proyector MX (YouTube).

Sources: Joey Nolfi (Entertainment Weekly), Wikipedia and .

Published on November 03, 2018 23:00

November 2, 2018

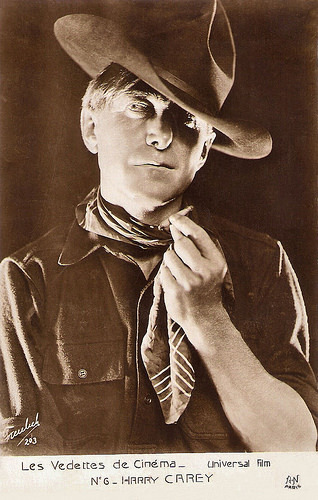

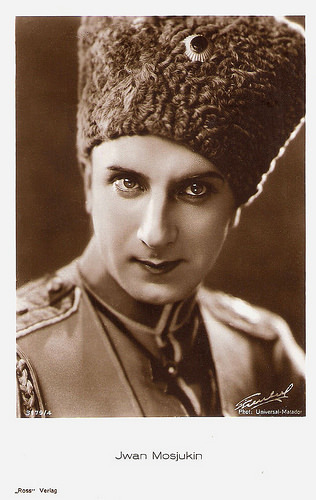

Photo by Freulich

Polish-born photographer Roman Freulich (1898–1974) was a pioneer in the Hollywood film industry, who worked for Universal and later for Republic. He made countless popular glamour shots of the stars which were also used for many European film star postcards, but he also did still photography for several classic films and made some interesting independent films. His brother Jack and nephew Henry were also well known Hollywood photographers.

Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 105/1. Photo: Universal Pictures Corp. Publicity still for The Man Who Laughs (Paul Leni, 1928).

Harry Carey. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the series Les Vedettes de Cinema, no. 6. Photo: Universal Film / Roman Freulich, no. 203.

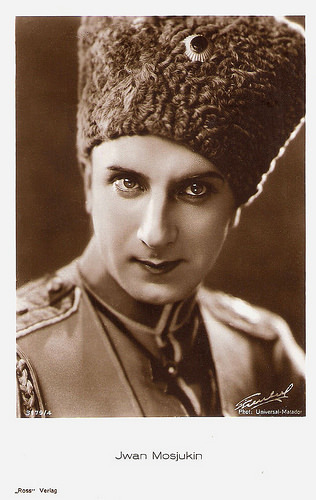

Ivan Mozzhukhin . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3179/4, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal / Matador. Publicity still for Surrender (Edward Sloman, 1927).

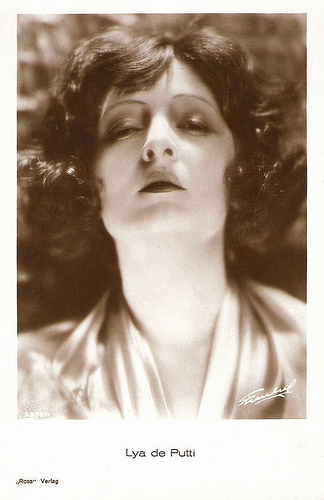

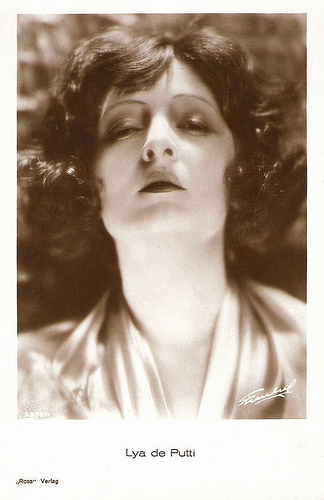

Lya de Putti . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3370/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

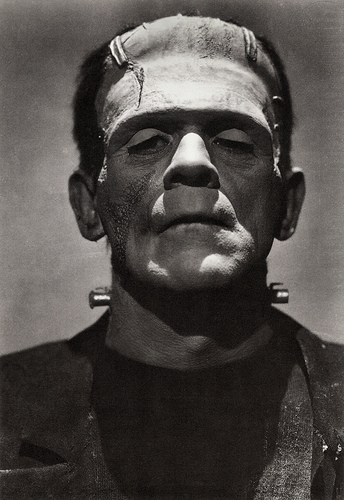

Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester. American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 233/007. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal Pictures. Publicity still for The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935).

Universal

Roman Freulich was born in 1898 in Czestochowa, Poland, Russian Empire (now Czestochowa, Slaskie, Poland). His parents were no longer young — Isaac Freulich was probably about 50 in 1898 and Nisla was 41. At Roman’s birth, his oldest sibling, his sister Sura Rifka was 20. His oldest brother Jacob, was 18.

He attended both grammar school and gymnasium — the equivalent of an American high school. He was quick to learn and did well in his studies — he became proficient in Russian, Polish, German and Yiddish — and acquired a taste for art, literature and classical music.

As a young teen he became active in the Jewish Socialist movement. Probably against the wishes of his mother and his father he began distributing literature for the movement in his after school time.

Late in 1912, Roman’s after school political activities became worrisome, and he immigrated with his father and a sister to the United States to join his eldest brother Jack (Jacob) in the Bronx. Freulich trained with New York photographer Samuel Lumiere.

In 1920, Freulich moved to Hollywood, where his brother Jack had become a portrait photographer at Universal Pictures. Jack's son, Henry Freulich, would also become a well known still photographer in Hollywood during the 1920s.

According to IMDb , Roman did the still photography for the silent film Outside the Law (Tod Browning, 1920), but it probably was his brother Jack while Roman was confined to a Sanatorium at the time.

In October 1920, Jack had checked Roman into the Barlow Tubercular Sanatorium in Chavez Ravine near downtown Los Angeles. Roman spent the next 15 months of his life there.

In 1922, Roman met his future wife, Katia Merkin. After his honeymoon, a job as a still photographer at Universal was waiting for Roman in California.

During his first 12 years at Universal, he worked closely with his brother and undoubtedly learned a great deal about production work, publicity shots and portraiture.

Among the films for which he did the still photography are The Phantom of the Opera (Rupert Julian, 1925) with Lon Chaney , The Man Who Laughs (Paul Leni, 1928) starring Conrad Veidt , All Quiet on the Western Front (Lewis Milestone, 1930), and Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931) featuring Bela Lugosi .

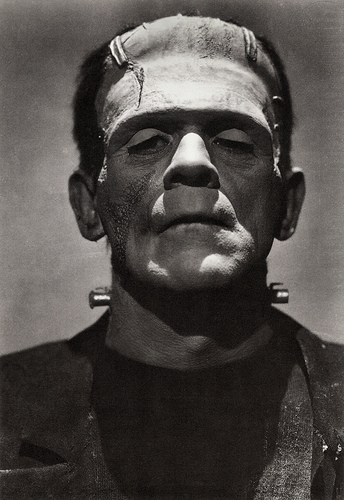

He also did the still photography for the horror films by James Whale, Frankenstein (James Whale, 1930) with Colin Clive and Boris Karloff , The Old Dark House (James Whale, 1932), The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933) featuring Claude Rains, and The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935) with Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester.

Another horror classic for which he did the still photography is The Black Cat (Edward G. Ulmer, 1934) starring both Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi .

Later in the 1930s, he photographed for Universal such musicals as the Deanna Durbin vehicles One Hundred Men And A Girl (Henry Koster, 1937) and Mad About Music (Norman Taurog, 1938) and The Under-Pup (Richard Wallace, 1939) with Gloria Jean.

In 1941, 1942, 1944, and 1947 he won awards at the Hollywood Studio Still Photography Show, sponsored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

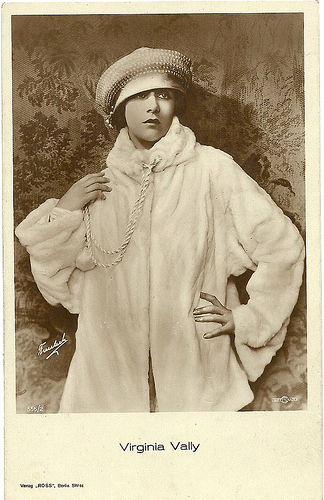

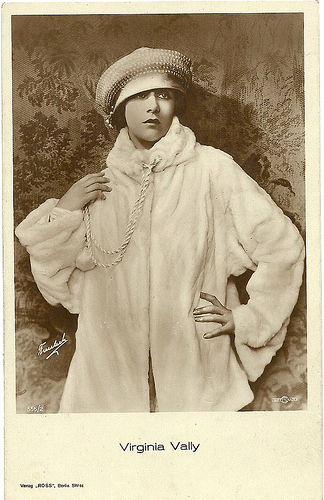

Virginia Vally. German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 556/2, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich. Collection: Didier Hanson.

Eddie Polo . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 587/1. Photo: Roman Freulich / Transocean-Film Co., Berlin.

Art Acord. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 712/2, 1925-1926. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal.

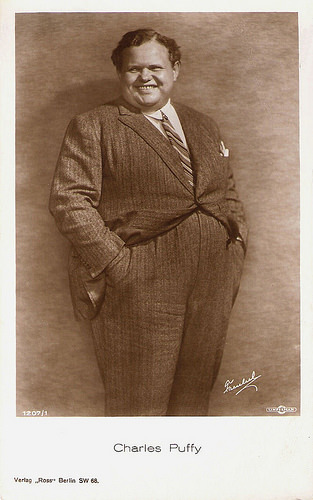

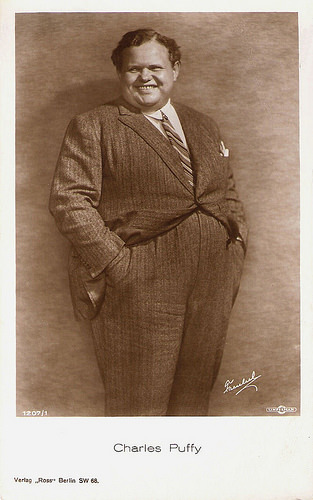

Charles Puffy . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1207/1, 1927-1928. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman (Universal).

André Mattoni . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3064/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Republic

In 1944, Roman Freulich was offered a position at Republic Studios as head of its still department. During his 13 years at Republic the Western played the same role as the horror film had played at Universal — it was the company bread and butter.

Thus photographs of John Wayne, Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, 'Wild Bill' Elliot, Gabby Hayes, Gene Autrey and the Sons of the Pioneers began to take a prominent place in Roman’s portfolio.

He photographed Roy Rogers Westerns like Don't Fence Me In (John English, 1945) but also She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (John Ford, 1949), Sands of Iwo Jima (Allan Dwan, 1949) and John Ford’s The Quiet Man (1952), all starring John Wayne.

In the late 1950s, after Republic ceased production, Freulich freelanced, mostly for United Artists, until the mid-1960s. He worked on such B-films as the prostitution drama Vice Raid (Edward L. Cahn, 1959) with Mamie van Doren , and the Western Young Jesse James (William F. Claxton, 1960).

Freulich's immigration to America and the loss of his family members who had remained in Poland during the Holocaust are two legacies that distinguished Freulich from his fellow cameramen in Hollywood. In 1938. Freulich had made a trip to Poland in part to encourage family members to immigrate to the United States. He made photos of his family in Lodz and also made images of street scenes in Łódź, and two images taken in Warsaw.

The remarkable output of Freulich's independent work, consisting of film projects that ventured far beyond the relative professional shelter provided by his popular glamour shots. Freulich sought to give voice to the voiceless as evidenced in his self-produced short film Broken Earth (Roman Freulich, 1936) – the first film to feature a black actor (Clarence Muse) in a starring role – as well as his collaborations with the actor Paul Robeson.

Freulich authored Soldiers in Judea, Stories and Vignettes of the Jewish Legion (1964) and The Hill of Life (1968), a fictionalised biography of Joseph Trumpeldor.

Two years later, he worked for the last time as still photographer on a film, Tora, Tora, Tora (Richard Fleischer, Kinji Fukasaku, 1970).

Roman Freulich died in 1974 in West Los Angeles. He was 76.

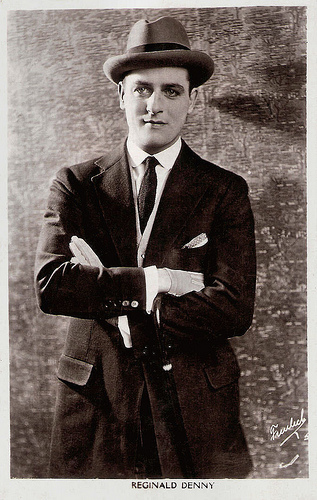

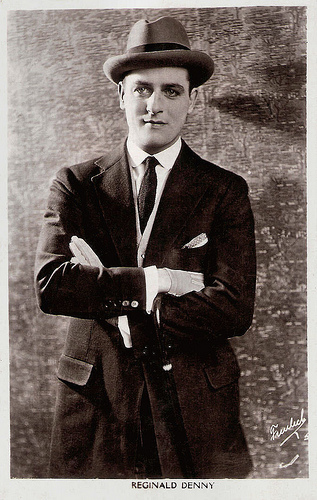

Reginald Denny . British postcard in the Picturegoer series, no. 74. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Ivan Mozzhukhin . German postcard by Ross-Verlag, no. 1265/1, 1927-1928. Photo: Roman Freulich. Publicity still for Surrender (Edward Sloman, 1927).

Lya de Putti . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3178/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Conrad Veidt . German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 3919/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Boris Karloff . American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 233/06. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal Pictures. Publicity still for Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931).

Sources: Joan Abramson (The Halborns), Sarah A. Buchanan (History of Photography), Mptv, Wikipedia and

November and December will be EFSP's Hollywood months with European postcards of American film stars and films. From the 1920s on, the Hollywood studios had their own photo departments, so we will stop with our series on photographers and start a new series on the Hollywood studios. It starts next Saturday, 10 November, with Warner Bros.

Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 105/1. Photo: Universal Pictures Corp. Publicity still for The Man Who Laughs (Paul Leni, 1928).

Harry Carey. French postcard by A.N., Paris, in the series Les Vedettes de Cinema, no. 6. Photo: Universal Film / Roman Freulich, no. 203.

Ivan Mozzhukhin . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3179/4, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal / Matador. Publicity still for Surrender (Edward Sloman, 1927).

Lya de Putti . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3370/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester. American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 233/007. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal Pictures. Publicity still for The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935).

Universal

Roman Freulich was born in 1898 in Czestochowa, Poland, Russian Empire (now Czestochowa, Slaskie, Poland). His parents were no longer young — Isaac Freulich was probably about 50 in 1898 and Nisla was 41. At Roman’s birth, his oldest sibling, his sister Sura Rifka was 20. His oldest brother Jacob, was 18.

He attended both grammar school and gymnasium — the equivalent of an American high school. He was quick to learn and did well in his studies — he became proficient in Russian, Polish, German and Yiddish — and acquired a taste for art, literature and classical music.

As a young teen he became active in the Jewish Socialist movement. Probably against the wishes of his mother and his father he began distributing literature for the movement in his after school time.

Late in 1912, Roman’s after school political activities became worrisome, and he immigrated with his father and a sister to the United States to join his eldest brother Jack (Jacob) in the Bronx. Freulich trained with New York photographer Samuel Lumiere.

In 1920, Freulich moved to Hollywood, where his brother Jack had become a portrait photographer at Universal Pictures. Jack's son, Henry Freulich, would also become a well known still photographer in Hollywood during the 1920s.

According to IMDb , Roman did the still photography for the silent film Outside the Law (Tod Browning, 1920), but it probably was his brother Jack while Roman was confined to a Sanatorium at the time.

In October 1920, Jack had checked Roman into the Barlow Tubercular Sanatorium in Chavez Ravine near downtown Los Angeles. Roman spent the next 15 months of his life there.

In 1922, Roman met his future wife, Katia Merkin. After his honeymoon, a job as a still photographer at Universal was waiting for Roman in California.

During his first 12 years at Universal, he worked closely with his brother and undoubtedly learned a great deal about production work, publicity shots and portraiture.

Among the films for which he did the still photography are The Phantom of the Opera (Rupert Julian, 1925) with Lon Chaney , The Man Who Laughs (Paul Leni, 1928) starring Conrad Veidt , All Quiet on the Western Front (Lewis Milestone, 1930), and Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931) featuring Bela Lugosi .

He also did the still photography for the horror films by James Whale, Frankenstein (James Whale, 1930) with Colin Clive and Boris Karloff , The Old Dark House (James Whale, 1932), The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933) featuring Claude Rains, and The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935) with Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester.

Another horror classic for which he did the still photography is The Black Cat (Edward G. Ulmer, 1934) starring both Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi .

Later in the 1930s, he photographed for Universal such musicals as the Deanna Durbin vehicles One Hundred Men And A Girl (Henry Koster, 1937) and Mad About Music (Norman Taurog, 1938) and The Under-Pup (Richard Wallace, 1939) with Gloria Jean.

In 1941, 1942, 1944, and 1947 he won awards at the Hollywood Studio Still Photography Show, sponsored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Virginia Vally. German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 556/2, 1919-1924. Photo: Roman Freulich. Collection: Didier Hanson.

Eddie Polo . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 587/1. Photo: Roman Freulich / Transocean-Film Co., Berlin.

Art Acord. German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 712/2, 1925-1926. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal.

Charles Puffy . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1207/1, 1927-1928. Photo: Roman Freulich / Unfilman (Universal).

André Mattoni . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3064/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Republic

In 1944, Roman Freulich was offered a position at Republic Studios as head of its still department. During his 13 years at Republic the Western played the same role as the horror film had played at Universal — it was the company bread and butter.

Thus photographs of John Wayne, Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, 'Wild Bill' Elliot, Gabby Hayes, Gene Autrey and the Sons of the Pioneers began to take a prominent place in Roman’s portfolio.

He photographed Roy Rogers Westerns like Don't Fence Me In (John English, 1945) but also She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (John Ford, 1949), Sands of Iwo Jima (Allan Dwan, 1949) and John Ford’s The Quiet Man (1952), all starring John Wayne.

In the late 1950s, after Republic ceased production, Freulich freelanced, mostly for United Artists, until the mid-1960s. He worked on such B-films as the prostitution drama Vice Raid (Edward L. Cahn, 1959) with Mamie van Doren , and the Western Young Jesse James (William F. Claxton, 1960).

Freulich's immigration to America and the loss of his family members who had remained in Poland during the Holocaust are two legacies that distinguished Freulich from his fellow cameramen in Hollywood. In 1938. Freulich had made a trip to Poland in part to encourage family members to immigrate to the United States. He made photos of his family in Lodz and also made images of street scenes in Łódź, and two images taken in Warsaw.

The remarkable output of Freulich's independent work, consisting of film projects that ventured far beyond the relative professional shelter provided by his popular glamour shots. Freulich sought to give voice to the voiceless as evidenced in his self-produced short film Broken Earth (Roman Freulich, 1936) – the first film to feature a black actor (Clarence Muse) in a starring role – as well as his collaborations with the actor Paul Robeson.

Freulich authored Soldiers in Judea, Stories and Vignettes of the Jewish Legion (1964) and The Hill of Life (1968), a fictionalised biography of Joseph Trumpeldor.

Two years later, he worked for the last time as still photographer on a film, Tora, Tora, Tora (Richard Fleischer, Kinji Fukasaku, 1970).

Roman Freulich died in 1974 in West Los Angeles. He was 76.

Reginald Denny . British postcard in the Picturegoer series, no. 74. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Ivan Mozzhukhin . German postcard by Ross-Verlag, no. 1265/1, 1927-1928. Photo: Roman Freulich. Publicity still for Surrender (Edward Sloman, 1927).

Lya de Putti . German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3178/2, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Conrad Veidt . German postcard by Ross Verlag, Berlin, no. 3919/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Roman Freulich.

Boris Karloff . American postcard by Classico San Francisco, no. 233/06. Photo: Roman Freulich / Universal Pictures. Publicity still for Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931).

Sources: Joan Abramson (The Halborns), Sarah A. Buchanan (History of Photography), Mptv, Wikipedia and

November and December will be EFSP's Hollywood months with European postcards of American film stars and films. From the 1920s on, the Hollywood studios had their own photo departments, so we will stop with our series on photographers and start a new series on the Hollywood studios. It starts next Saturday, 10 November, with Warner Bros.

Published on November 02, 2018 23:00

November 1, 2018

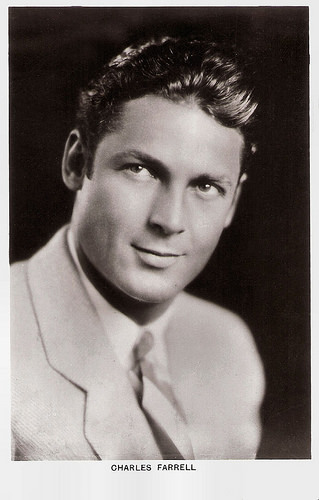

Charles Farrell

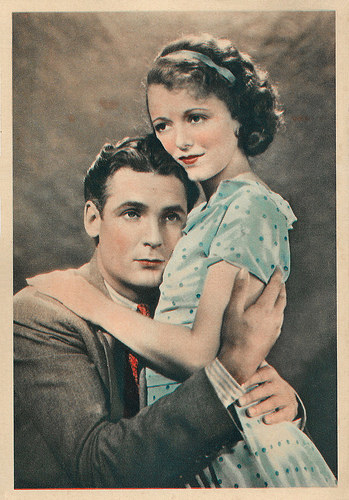

Good-looking American actor Charles Farrell (1900-1990) was a Hollywood matinee idol of the Jazz Age and Depression era. Now, he seems forgotten, but between 1927 and 1934, he was a very popular team with Janet Gaynor. They appeared in 12 screen romances, including 7th Heaven (1927), Street Angel (1928), and Lucky Star (1929). Farrell retired from films in the early 1940s, but TV audiences of the 1950s would see him as Gale Storm's widower dad in the popular television series My Little Margie (1952-1955).

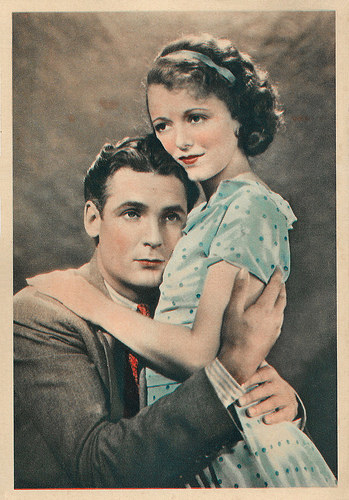

Italian postcard offered by Cioccolata Lurati, no. 124. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Seventh Heaven (Frank Borzage, 1927) with Janet Gaynor.

French postcard by Cinémagazine Edition (CE), Paris, no. 821. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Lucky Star (Frank Borzage, 1929) with Janet Gaynor.

British postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3917/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Fazil (Howard Hawks, 1928) with Greta Nissen .

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5889. Photo: Max Munn Autrey / Fox.

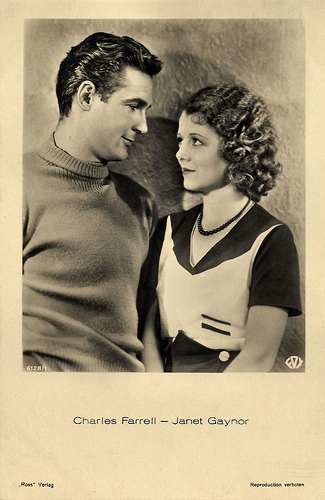

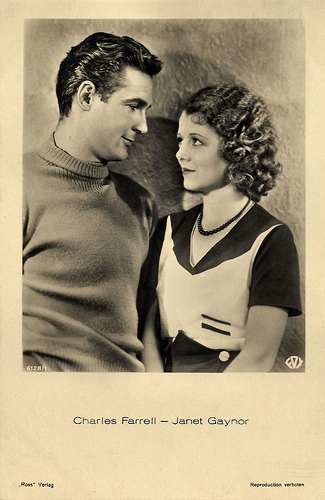

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6128/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for The First Year (William K. Howard, 1932) with Janet Gaynor .

The pivotal role as the Parisian sewer cleaner Chico

Charles David Farrell was born in 1900 in Onset, Massachusetts, the only son in his family. His father owned a lunch counter where films were shown on the upper floor which introduced Farrell to the world of cinema.

He briefly attended Boston University to study business while playing in the football team but dropped out to become an actor in the theatre. This didn’t go well with his family, especially his father, so Farrell was on his own. He took any acting job possible that would get him financially and professionally closer to his goal of being in the cinema.

The handsome young actor decided to move to California and to try his luck in Hollywood. For Paramount Pictures, Farrell did extra work for films ranging from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Wallace Worsley, 1923) with Lon Chaney , Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), and The Cheat (George Fitzmaurice, 1923) with Pola Negri.

Farrell continued to work throughout the next few years in relatively minor roles without much success. After three years as an extra he was given a good role in Old Ironsides (James Cruze, 1926). Then his big break came when Fox Studios signed him and gave him the pivotal role as the Parisian sewer cleaner Chico in the romantic drama 7th Heaven (Frank Borzage, 1927). He was paired with fellow newcomer Janet Gaynor . The film was a public and critical success and won an Academy Award.

The studio noticed the audiences growing a craze for Farrell and Gaynor and they would go on to co-star in more than a dozen films throughout the late 1920s and into the talkie era of the early 1930s. The plots of the Gaynor-Farrell films were fit for a fairytale book where love conquers all and the good prevail, with convincing acting that makes you believe it.

Director of three of these films was Frank Borzage, known for stories set in a surreal or ethereal like world. Farrell and Gaynor were romantically involved from about 1926 until her first marriage in 1929. Shaken by the death of his close friend, actor Fred Thomson, Farrell proposed marriage to Gaynor around 1928, but the couple was never married.

Years later, Gaynor explained her breakup with Farrell: "I think we loved each other more than we were 'in love.' He played polo, he went to the Hearst Ranch for wild weekends with Marion Davies, he got around to the parties - he was a big, brawny, outdoors type... I was not a party girl... Charlie pressed me to marry him, but we had too many differences. In my era, you didn't live together. It just wasn't done. So I married a San Francisco businessman, Lydell Peck, just to get away from Charlie."

Another success for Farrell was The Red Dance (Raoul Walsh, 1928) in which Dolores del Rio co-starred as a poor girl-turned-dancer who falls in love with Farrell’s character of Grand Duke Eugene during the Bolshevik Revolution. Two months before the stock market crash, Farrell and Gaynor starred in the unique and heartfelt WWI love story, Lucky Star (Frank Borzage, 1929).

The Depression was just beginning when Farrell’s made his last and one of his best silents film, City Girl (F.W. Murnau, 1930). He plays Lem, a young man from the country sent to the city for business who falls in love with the waitress at the lunch counter named Kate (Mary Duncan). Rachel at Vintage Stardust : "His acting brought elegance even during the most emotional scenes and refreshed the image of masculinity in film even after he successfully transitioned into sound. Oh and he was one of the first to go nude in film (in The River from 1929 (sic) there’s a brief scene where he swam nude and is about to get out of the water completely before he sees a woman nearby.)" Sadly, Frank Borzage's masterpiece The River (1928) is partially lost.

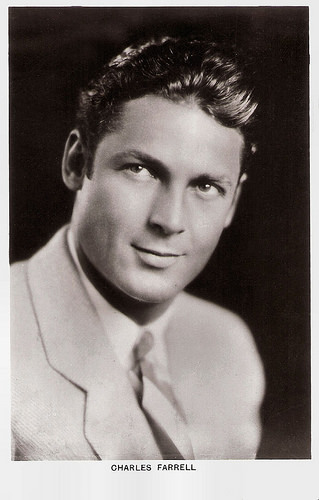

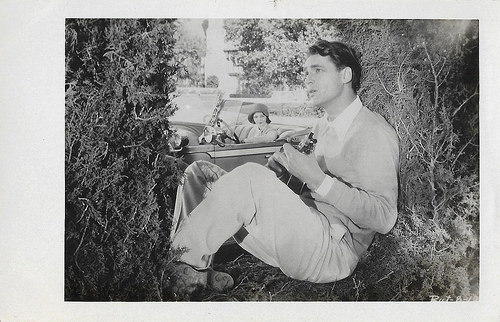

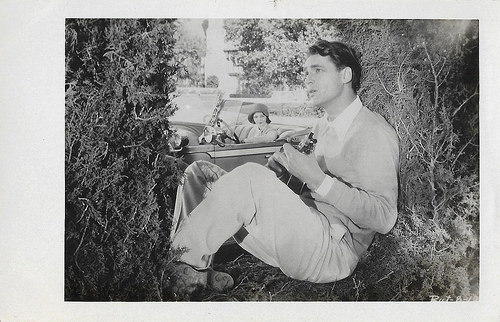

British postcard in the Colourgraph Series, London, no. C 65.

British card.

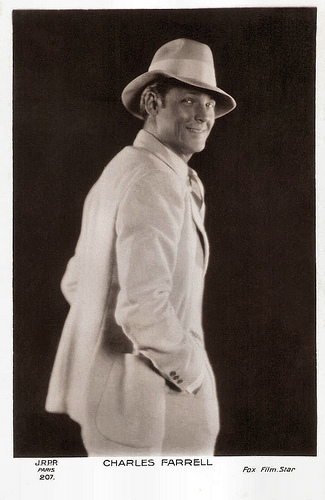

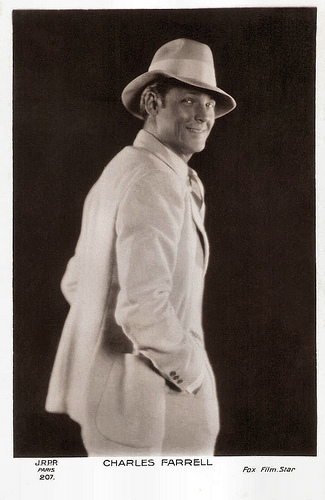

French postcard by J.R.P.R., Paris, no. 207. Photo: Fox.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 827. Photo: Max Munn Autrey / Fox Film. Publicity still for The Red Dance (Raoul Walsh, 1928) wirh Dolores del Rio .

British postcard, no. 9 of a fifth series of 25 Cinema Stars, issued with Sarony Cigarettes. Photo: publicity still for The Red Dance (Raoul Walsh, 1928).

Bringing a new definition of men in cinema

Unlike many of his silent screen peers, Charles Farrell had no 'voice troubles' and remained a publicly popular actor throughout the sound era. Rachel at Vintage Stardust : "Well mannered and athletically built, Farrell’s roles were dramatic but often romantic leads that brought a new definition of men in cinema. His gentleness in his characters created the idea that men could be sensitive and kind yet strong at the same time. Not to say that men from this era couldn’t be this way in real life but to it was rare in film to depict men as being vulnerable."

In 1931 he married actress Virginia Valli, with whom he stayed together until her death in 1968. In the 1930s, Farrell became a resident of the desert city of Palm Springs, California. In 1934, he opened the popular Palm Springs Racquet Club in the city with his business partner, fellow actor Ralph Bellamy.

By the mid 1930s his career declined. Rumours point to his personal life or lack of memorable scripts. The type of leading men was also changing with the Depression. The scripts Farrell received included musicals which did not allow him to showcase his acting range. An exception was Change of Heart (John G. Blystone, 1934).

During World War II, Farrell served in the Navy. A major player in the developing prosperity of Palm Springs in the 1930s through the 1960s, Farrell was elected to the city council in 1946 and elected mayor of the community in 1948, a position that he held until he submitted his resignation in 1953 due to a return to acting.

In 1952, more than a decade after his career in motion pictures had ended, Farrell began appearing on the television series My Little Margie, which aired on CBS and NBC between 1952 and 1955. He played the role of the widower Vern Albright, the father of a young woman, Margie Albright (Gale Storm), with a knack for getting into trouble. In 1956, Farrell starred in his own television program, The Charles Farrell Show.

For the remainder of his life Farrell managed the Palm Springs Racquet Club until the late 1960s, and kept out of the Hollywood spotlight. He died of a heart attack in 1990.

At the time of his death, he felt forgotten as an actor and his films were too dated to be appreciated. But in 1990, a 35mm print of his previously considered lost film Lucky Star (1929) was discovered in the Nederlands Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. It was restored for its 1990 revival premiere at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy. And audiences started a new craze for Farrell and Gaynor.

British postcard by Abdulla Cigarettes, no. 15. Photo: Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4171/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Fox.

Austrian postcard by Iris Verlag, no. 5995. Photo: Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4862/2. Photo: Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5001/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Fox. Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell in the early sound film Sunnyside Up (David Butler, 1929).

British postard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. 332.

Photo postcard delivered by the Dutch East Indies. Toko Ang West, Bandoeng. Photo: publicity still for High Society Blues (David Butler, 1930).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6452/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Delicious (David Butler, 1931) with Janet Gaynor .

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 71466/1, 1932-1933. Photo: Fox. With Janet Gaynor .

Sources: Rachel (Vintage Stardust), (IMDb), (IMDb), Wikipedia and .

Italian postcard offered by Cioccolata Lurati, no. 124. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Seventh Heaven (Frank Borzage, 1927) with Janet Gaynor.

French postcard by Cinémagazine Edition (CE), Paris, no. 821. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Lucky Star (Frank Borzage, 1929) with Janet Gaynor.

British postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3917/1, 1928-1929. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Fazil (Howard Hawks, 1928) with Greta Nissen .

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5889. Photo: Max Munn Autrey / Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6128/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for The First Year (William K. Howard, 1932) with Janet Gaynor .

The pivotal role as the Parisian sewer cleaner Chico

Charles David Farrell was born in 1900 in Onset, Massachusetts, the only son in his family. His father owned a lunch counter where films were shown on the upper floor which introduced Farrell to the world of cinema.

He briefly attended Boston University to study business while playing in the football team but dropped out to become an actor in the theatre. This didn’t go well with his family, especially his father, so Farrell was on his own. He took any acting job possible that would get him financially and professionally closer to his goal of being in the cinema.

The handsome young actor decided to move to California and to try his luck in Hollywood. For Paramount Pictures, Farrell did extra work for films ranging from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Wallace Worsley, 1923) with Lon Chaney , Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), and The Cheat (George Fitzmaurice, 1923) with Pola Negri.

Farrell continued to work throughout the next few years in relatively minor roles without much success. After three years as an extra he was given a good role in Old Ironsides (James Cruze, 1926). Then his big break came when Fox Studios signed him and gave him the pivotal role as the Parisian sewer cleaner Chico in the romantic drama 7th Heaven (Frank Borzage, 1927). He was paired with fellow newcomer Janet Gaynor . The film was a public and critical success and won an Academy Award.

The studio noticed the audiences growing a craze for Farrell and Gaynor and they would go on to co-star in more than a dozen films throughout the late 1920s and into the talkie era of the early 1930s. The plots of the Gaynor-Farrell films were fit for a fairytale book where love conquers all and the good prevail, with convincing acting that makes you believe it.

Director of three of these films was Frank Borzage, known for stories set in a surreal or ethereal like world. Farrell and Gaynor were romantically involved from about 1926 until her first marriage in 1929. Shaken by the death of his close friend, actor Fred Thomson, Farrell proposed marriage to Gaynor around 1928, but the couple was never married.

Years later, Gaynor explained her breakup with Farrell: "I think we loved each other more than we were 'in love.' He played polo, he went to the Hearst Ranch for wild weekends with Marion Davies, he got around to the parties - he was a big, brawny, outdoors type... I was not a party girl... Charlie pressed me to marry him, but we had too many differences. In my era, you didn't live together. It just wasn't done. So I married a San Francisco businessman, Lydell Peck, just to get away from Charlie."

Another success for Farrell was The Red Dance (Raoul Walsh, 1928) in which Dolores del Rio co-starred as a poor girl-turned-dancer who falls in love with Farrell’s character of Grand Duke Eugene during the Bolshevik Revolution. Two months before the stock market crash, Farrell and Gaynor starred in the unique and heartfelt WWI love story, Lucky Star (Frank Borzage, 1929).

The Depression was just beginning when Farrell’s made his last and one of his best silents film, City Girl (F.W. Murnau, 1930). He plays Lem, a young man from the country sent to the city for business who falls in love with the waitress at the lunch counter named Kate (Mary Duncan). Rachel at Vintage Stardust : "His acting brought elegance even during the most emotional scenes and refreshed the image of masculinity in film even after he successfully transitioned into sound. Oh and he was one of the first to go nude in film (in The River from 1929 (sic) there’s a brief scene where he swam nude and is about to get out of the water completely before he sees a woman nearby.)" Sadly, Frank Borzage's masterpiece The River (1928) is partially lost.

British postcard in the Colourgraph Series, London, no. C 65.

British card.

French postcard by J.R.P.R., Paris, no. 207. Photo: Fox.

Italian postcard by G.B. Falci, Milano, no. 827. Photo: Max Munn Autrey / Fox Film. Publicity still for The Red Dance (Raoul Walsh, 1928) wirh Dolores del Rio .

British postcard, no. 9 of a fifth series of 25 Cinema Stars, issued with Sarony Cigarettes. Photo: publicity still for The Red Dance (Raoul Walsh, 1928).

Bringing a new definition of men in cinema

Unlike many of his silent screen peers, Charles Farrell had no 'voice troubles' and remained a publicly popular actor throughout the sound era. Rachel at Vintage Stardust : "Well mannered and athletically built, Farrell’s roles were dramatic but often romantic leads that brought a new definition of men in cinema. His gentleness in his characters created the idea that men could be sensitive and kind yet strong at the same time. Not to say that men from this era couldn’t be this way in real life but to it was rare in film to depict men as being vulnerable."

In 1931 he married actress Virginia Valli, with whom he stayed together until her death in 1968. In the 1930s, Farrell became a resident of the desert city of Palm Springs, California. In 1934, he opened the popular Palm Springs Racquet Club in the city with his business partner, fellow actor Ralph Bellamy.

By the mid 1930s his career declined. Rumours point to his personal life or lack of memorable scripts. The type of leading men was also changing with the Depression. The scripts Farrell received included musicals which did not allow him to showcase his acting range. An exception was Change of Heart (John G. Blystone, 1934).

During World War II, Farrell served in the Navy. A major player in the developing prosperity of Palm Springs in the 1930s through the 1960s, Farrell was elected to the city council in 1946 and elected mayor of the community in 1948, a position that he held until he submitted his resignation in 1953 due to a return to acting.

In 1952, more than a decade after his career in motion pictures had ended, Farrell began appearing on the television series My Little Margie, which aired on CBS and NBC between 1952 and 1955. He played the role of the widower Vern Albright, the father of a young woman, Margie Albright (Gale Storm), with a knack for getting into trouble. In 1956, Farrell starred in his own television program, The Charles Farrell Show.

For the remainder of his life Farrell managed the Palm Springs Racquet Club until the late 1960s, and kept out of the Hollywood spotlight. He died of a heart attack in 1990.

At the time of his death, he felt forgotten as an actor and his films were too dated to be appreciated. But in 1990, a 35mm print of his previously considered lost film Lucky Star (1929) was discovered in the Nederlands Filmmuseum in Amsterdam. It was restored for its 1990 revival premiere at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy. And audiences started a new craze for Farrell and Gaynor.

British postcard by Abdulla Cigarettes, no. 15. Photo: Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4171/1, 1929-1930. Photo: Fox.

Austrian postcard by Iris Verlag, no. 5995. Photo: Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 4862/2. Photo: Fox.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 5001/1, 1930-1931. Photo: Fox. Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell in the early sound film Sunnyside Up (David Butler, 1929).

British postard in the Picturegoer series, London, no. 332.

Photo postcard delivered by the Dutch East Indies. Toko Ang West, Bandoeng. Photo: publicity still for High Society Blues (David Butler, 1930).

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6452/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Fox. Publicity still for Delicious (David Butler, 1931) with Janet Gaynor .

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 71466/1, 1932-1933. Photo: Fox. With Janet Gaynor .

Sources: Rachel (Vintage Stardust), (IMDb), (IMDb), Wikipedia and .

Published on November 01, 2018 23:00

October 31, 2018

My Fair Lady (1964)

Today, EFSP starts two months of posts with European postcards for Hollywood film stars and/or films. Thursday is the day for the film specials, and our first movie is special!

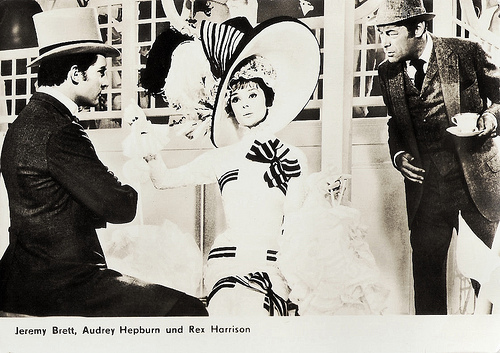

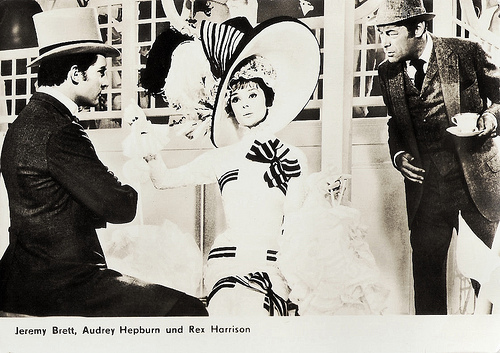

My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964) is one of the all-time great movie musicals, featuring classic songs by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe and the wonderful costumes by Cecil Beaton. The film won eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor for Rex Harrison in his legendary performance as misanthropic phonetics professor Henry Higgins. But Audrey Hepburn failed to be nominated for Best Actress. The Oscar was won by Julie Andrews for Mary Poppins, in what many observers saw as a backlash against Andrews' not being cast in the film after originating the role of Eliza on stage.

Spanish postcard by Oscarcolor. Photo: Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

East-German postcard by VEB-Progress Film-Vertrieb, Berlin, no. 2988. Retail price: 0,20 MDM. Photo: Warner Bros. Publicity still for My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964). Costume: Cecil Beaton.

The delusive dream of a man forming his own perfect woman

My Fair Lady was adapted by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe as a stage musical from the the 1913 brilliant stage play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw about the delusive dream of a man forming his own perfect woman.

In Edwardian London, Professor Henry Higgins, a scholar of phonetics, believes that the accent and tone of one's voice determines a person's prospects in society. Outside Covent Garden on a rainy evening in 1912, he boasts to a new acquaintance, Colonel Hugh Pickering, himself an expert in phonetics, that he could teach any person to speak in a way that he could pass them off as a duke or duchess at an embassy ball.

Higgins selects as an example a young flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, who has a strong Cockney accent. Higgins tells Pickering that, within six months, he could transform Eliza into a proper lady, simply by teaching her proper English.

Eliza's ambition is to work in a flower shop, but her thick accent makes her unsuitable. Having come from India to meet Higgins, Pickering is invited to stay with the professor. The following morning, face and hands freshly scrubbed, Eliza shows up at Higgins' home, offering to pay him to teach her to be a lady. Pickering is intrigued and offers to cover all expenses, should the experiment be successful.

My Fair Lady became the longest-running Broadway musical with in the leads Rex Harrison as Henry and Julie Andrews as Eliza. With the same cast, the musical also became a huge success in London. Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe made a great musical score. Most of their songs would become standards over the years that delighted audiences all over the world.

However, when Hollywood producer Jack Warner decided to make a film version of the hit musical, he felt that Andrews, at the time unknown beyond Broadway, wasn't bankable. He replaced her with Audrey Hepburn , a wonderful film actress but not a real singer. Hepburn's singing was dubbed by Marni Nixon, who had dubbed Natalie Wood in West Side Story (1961). Supporting roles went to Stanley Holloway (as Eliza's father, dustman Afred P. Doolittle), Gladys Cooper (Henry's mother Mrs. Higgins), Wilfrid Hyde-White (Colonel Pickering) and Jeremy Brett as the young playboy Freddy.

Dutch postcard by Int. Filmpers, Amsterdam, no. 1306. Photo: Warner Bros. Rex Harrison and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

Romanian postcard by Casa Filmului Acin, no. 261. Wilfrid Hyde-White and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

How could Eliza be played by anyone else than Julie Andrews?

With a production budget of $17 million, My Fair Lady became the most expensive film shot in the United States up to that time. George Cukor created an elegant, colourful adaptation of the beloved stage musical and Rex Harrison did another winning performance. But how did Audrey Hepburn ? The move to choose her over Julie Andrews had puzzled many in the theatrical world. How could Eliza be played by anyone else than Andrews?

Hepburn played the unschooled street urchin with a sweet, naive charm. Eliza goes through many forms of speech training, such as speaking with marbles in her mouth, enduring Higgins' harsh approach to teaching and his treatment of her personally. She makes little progress, but just as she, Higgins, and Pickering are about to give up, Eliza finally 'gets it'; she instantly begins to speak with an impeccable upper class accent. As the elegant and beautiful lady at the end of the film, Hepburn literally glows in the exquisite costumes designed for her by Cecil Beaton. She is a perfect match to Harrison's Higgins.

Ephraim Gadsby at IMDb: "The old furors over Audrey Hepburn seem silly in hindsight. Hepburn replaced Julie Andrews, a wonderful singer-actress who had created the role, not only on Broadway but in London. But Andrews was not a familiar face to movie-goers and no one knew if she'd hold an audience in the movies as in the live theaters. Too, Hepburn was an inspired choice, since her background probably would make Eliza Doolittle's transformation from flower-selling gutter-snipe into a lady of quality more believable (Hepburn's mother was a baroness)."

Richard Gilliam in his review at AllMovie: "Exquisitely produced by Warner Bros, it represents the zenith of the movie musical as an art form and as popular entertainment. Rex Harrison leads an impeccable cast, and, yes, that's Marni Nixon singing for Audrey Hepburn , but Hepburn is perfectly cast otherwise. The major star of the film is perhaps set designer/costume designer Cecil Beaton, whose visual contributions immediately impacted European and U.S. fashion trends."

In 1998, the American Film Institute named My Fair Lady (1964) the 91st greatest American film of all time. Critic Roger Ebert put the film on his 'Great Movies' list: "My Fair Lady is the best and most unlikely of musicals, during which I cannot decide if I am happier when the characters are talking or when they are singing. The songs are literate and beloved; some romantic, some comic, some nonsense, some surprisingly philosophical, every single one wonderful."

East-German postcard by VEB-Progress Film-Vertrieb, Berlin, no. 2989. Retail price: 0,20 MDM. Photo: Warner Bros. Publicity still for My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964) with Audrey Hepburn , Jeremy Brett and Rex Harrison .

East-German postcard by VEB-Progress Film-Vertrieb, Berlin, no. 3028. Retail price: 0,20 MDM. Photo: Warner Bros. Publicity still for My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

Trailer My Fair Lady (1964). Source: YouTube (ManUtd1962).

Sources: Roger Ebert, Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Richard Gilliam (AllMovie), Ephraim Gadsby (IMDb), Dennis Littrell (IMDb), Wikipedia and IMDb.

My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964) is one of the all-time great movie musicals, featuring classic songs by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe and the wonderful costumes by Cecil Beaton. The film won eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor for Rex Harrison in his legendary performance as misanthropic phonetics professor Henry Higgins. But Audrey Hepburn failed to be nominated for Best Actress. The Oscar was won by Julie Andrews for Mary Poppins, in what many observers saw as a backlash against Andrews' not being cast in the film after originating the role of Eliza on stage.

Spanish postcard by Oscarcolor. Photo: Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

East-German postcard by VEB-Progress Film-Vertrieb, Berlin, no. 2988. Retail price: 0,20 MDM. Photo: Warner Bros. Publicity still for My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964). Costume: Cecil Beaton.

The delusive dream of a man forming his own perfect woman

My Fair Lady was adapted by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe as a stage musical from the the 1913 brilliant stage play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw about the delusive dream of a man forming his own perfect woman.

In Edwardian London, Professor Henry Higgins, a scholar of phonetics, believes that the accent and tone of one's voice determines a person's prospects in society. Outside Covent Garden on a rainy evening in 1912, he boasts to a new acquaintance, Colonel Hugh Pickering, himself an expert in phonetics, that he could teach any person to speak in a way that he could pass them off as a duke or duchess at an embassy ball.

Higgins selects as an example a young flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, who has a strong Cockney accent. Higgins tells Pickering that, within six months, he could transform Eliza into a proper lady, simply by teaching her proper English.

Eliza's ambition is to work in a flower shop, but her thick accent makes her unsuitable. Having come from India to meet Higgins, Pickering is invited to stay with the professor. The following morning, face and hands freshly scrubbed, Eliza shows up at Higgins' home, offering to pay him to teach her to be a lady. Pickering is intrigued and offers to cover all expenses, should the experiment be successful.

My Fair Lady became the longest-running Broadway musical with in the leads Rex Harrison as Henry and Julie Andrews as Eliza. With the same cast, the musical also became a huge success in London. Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe made a great musical score. Most of their songs would become standards over the years that delighted audiences all over the world.

However, when Hollywood producer Jack Warner decided to make a film version of the hit musical, he felt that Andrews, at the time unknown beyond Broadway, wasn't bankable. He replaced her with Audrey Hepburn , a wonderful film actress but not a real singer. Hepburn's singing was dubbed by Marni Nixon, who had dubbed Natalie Wood in West Side Story (1961). Supporting roles went to Stanley Holloway (as Eliza's father, dustman Afred P. Doolittle), Gladys Cooper (Henry's mother Mrs. Higgins), Wilfrid Hyde-White (Colonel Pickering) and Jeremy Brett as the young playboy Freddy.

Dutch postcard by Int. Filmpers, Amsterdam, no. 1306. Photo: Warner Bros. Rex Harrison and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

Romanian postcard by Casa Filmului Acin, no. 261. Wilfrid Hyde-White and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

How could Eliza be played by anyone else than Julie Andrews?

With a production budget of $17 million, My Fair Lady became the most expensive film shot in the United States up to that time. George Cukor created an elegant, colourful adaptation of the beloved stage musical and Rex Harrison did another winning performance. But how did Audrey Hepburn ? The move to choose her over Julie Andrews had puzzled many in the theatrical world. How could Eliza be played by anyone else than Andrews?

Hepburn played the unschooled street urchin with a sweet, naive charm. Eliza goes through many forms of speech training, such as speaking with marbles in her mouth, enduring Higgins' harsh approach to teaching and his treatment of her personally. She makes little progress, but just as she, Higgins, and Pickering are about to give up, Eliza finally 'gets it'; she instantly begins to speak with an impeccable upper class accent. As the elegant and beautiful lady at the end of the film, Hepburn literally glows in the exquisite costumes designed for her by Cecil Beaton. She is a perfect match to Harrison's Higgins.

Ephraim Gadsby at IMDb: "The old furors over Audrey Hepburn seem silly in hindsight. Hepburn replaced Julie Andrews, a wonderful singer-actress who had created the role, not only on Broadway but in London. But Andrews was not a familiar face to movie-goers and no one knew if she'd hold an audience in the movies as in the live theaters. Too, Hepburn was an inspired choice, since her background probably would make Eliza Doolittle's transformation from flower-selling gutter-snipe into a lady of quality more believable (Hepburn's mother was a baroness)."

Richard Gilliam in his review at AllMovie: "Exquisitely produced by Warner Bros, it represents the zenith of the movie musical as an art form and as popular entertainment. Rex Harrison leads an impeccable cast, and, yes, that's Marni Nixon singing for Audrey Hepburn , but Hepburn is perfectly cast otherwise. The major star of the film is perhaps set designer/costume designer Cecil Beaton, whose visual contributions immediately impacted European and U.S. fashion trends."

In 1998, the American Film Institute named My Fair Lady (1964) the 91st greatest American film of all time. Critic Roger Ebert put the film on his 'Great Movies' list: "My Fair Lady is the best and most unlikely of musicals, during which I cannot decide if I am happier when the characters are talking or when they are singing. The songs are literate and beloved; some romantic, some comic, some nonsense, some surprisingly philosophical, every single one wonderful."