Paul van Yperen's Blog, page 252

November 30, 2018

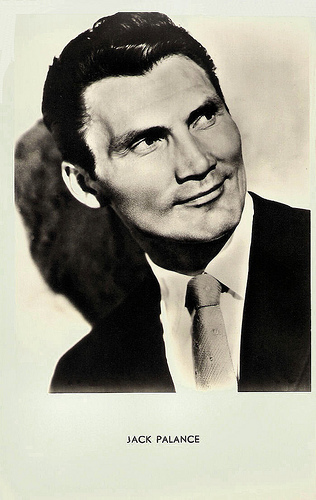

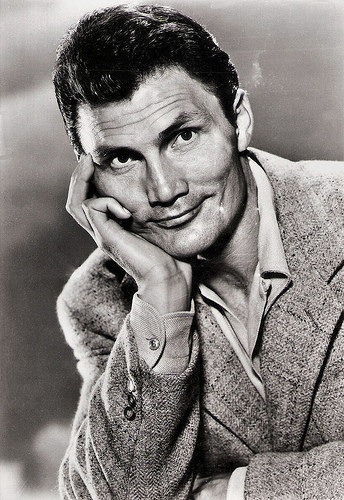

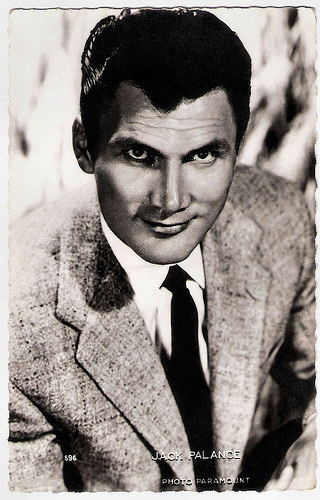

Photo by Columbia

Columbia Pictures or Columbia is one of the 'Big Six' major American film studios, and was one of the 'Little Three' among the eight major film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. Studio Mogul was the notoriously hard-driving and vulgar Harry Cohn. Initially Columbia had the worst reputation and smallest budgets, but in the late 1920s the studio began to grow, spurred by a successful association with director Frank Capra. In the 1930s, Columbia became one of the primary homes of the screwball comedy, and contract stars were Jean Arthur and Cary Grant. In the 1940s, Rita Hayworth became Columbia's premier star and Rosalind Russell, Glenn Ford, and William Holden also became major stars at the studio. Today, it has become the world's fifth largest major film studio and is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group.

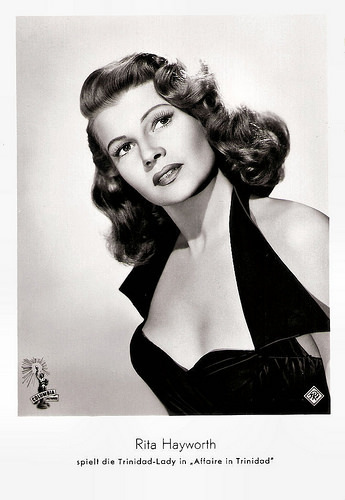

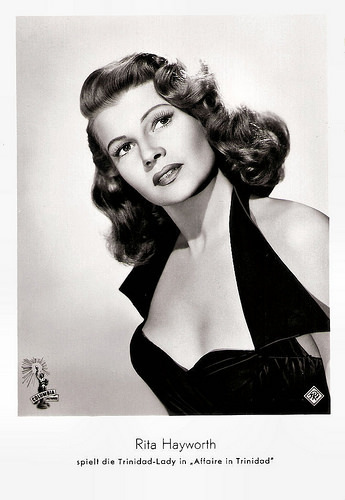

Rita Hayworth . Belgian postcard by Victoria, Brussels, no. 639. Photo: Columbia Pictures.

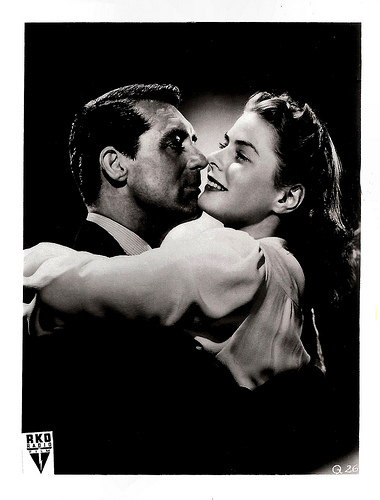

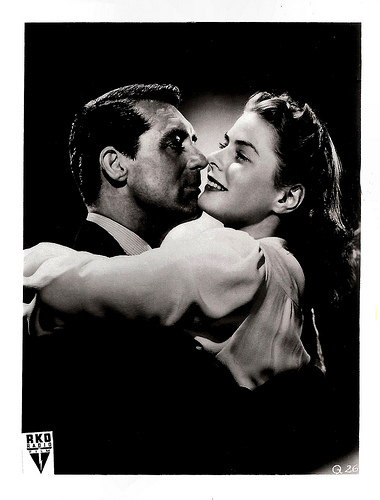

Cary Grant. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 735c. Photo: Columbia.

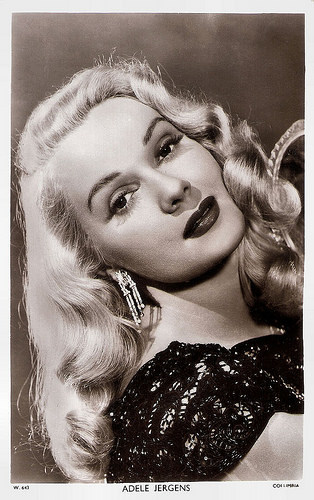

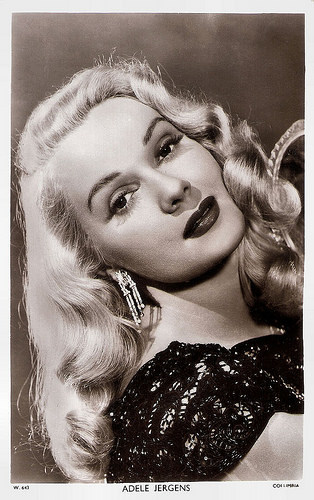

Adele Jergens. British postcard in Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 643. Photo: Columbia.

Claudette Colbert . Dutch postcard by J.S.A.. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Tomorrow is Forever (Irving Pichel, 1946).

Burt Lancaster . German postcard by Franz Josef Rüdel, Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 858. Photo: Columbia-Film. Publicity still for From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953).

The Corned Beef and Cabbage Studio

Columbia was founded in June 1918 as Cohn-Brandt-Cohn (CBC) Film Sales by brothers Jack and Harry Cohn and Jack's best friend Joe Brandt. Jack had worked for Carl Laemmle at Universal, Joe had been Laemmle’s executive secretary and Jack’s younger brother Harry, had also worked at Universal.They released their first feature film in August 1922. Brandt was president of CBC Film Sales, handling sales, marketing and distribution from New York along with Jack Cohn, while Harry Cohn ran production in Hollywood.

The studio's early productions were low-budget short subjects: 'Screen Snapshots', the 'Hall Room Boys' (the vaudeville duo of Edward Flanagan and Neely Edwards), and the Chaplin imitator Billy West. The start-up CBC leased space in a Poverty Row studio on Hollywood's famously low-rent Gower Street. Among Hollywood's elite, the studio's small-time reputation led some to joke that CBC stood for 'Corned Beef and Cabbage'. Brandt eventually tired of dealing with the Cohn brothers, and he sold his one-third stake to Harry Cohn, who took over as president.

In an effort to improve its image, the Cohn brothers renamed the company Columbia Pictures Corporation in 1924. Cohn remained head of production as well, thus concentrating enormous power in his hands. He would run Columbia for the next 34 years, the second-longest tenure of any studio chief, behind only Warner Bros.' Jack L. Warner. Even in an industry rife with nepotism, Columbia was particularly notorious for having a number of Harry and Jack's relatives in high positions. Humorist Robert Benchley called it the Pine Tree Studio, "because it has so many Cohns".

Columbia's product line consisted mostly of moderately budgeted features and short subjects including comedies, sports films, various serials, and cartoons. Columbia gradually moved into the production of higher-budget fare, eventually joining the second tier of Hollywood studios along with United Artists and Universal. Like United Artists and Universal, Columbia was a horizontally integrated company. It controlled production and distribution; it did not own any theatres.

Helping Columbia's climb was the arrival of an ambitious director, Frank Capra. Between 1927 and 1939, Capra constantly pushed Cohn for better material and bigger budgets. A string of hits he directed in the early and mid 1930s solidified Columbia's status as a major studio. In particular, It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934) with Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert put Columbia on the map. It won the Academy Award for Best Film of 1934.

Until then, Columbia's very existence had depended on theatre owners willing to take its films, since as mentioned above it didn't have a theatre network of its own. Other Capra-directed hits followed, including Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (Frank Capra, 1936), the original version of Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937) with Ronald Colman , You Can’t Take it With You (Frank Capra, 1938), which was Capra's highest-grossing picture at Columbia, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939), which made James Stewart a major star.

Capra but also Howard Hawks and others made some of the finest screwball comedies of the 1930s for Columbia: The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937), Holiday (George Cukor, 1938), and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940), all starring Cary Grant. After Capra’s departure in 1939, Columbia languished because leading directors were reluctant to work for the notoriously hard-driving and vulgar Cohn.

In 1938, the addition of B. B. Kahane as Vice President would produce Charles Vidor's Those High Gray Walls (Charles Vidor, 1939), and The Lady in Question (Charles Vidor, 1940), the first joint film of Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford. Kahane would later become the President of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1959, until his death a year later.

Tullio Carminati and Grace Moore. British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. P 151. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for One Night of Love (Victor Schertzinger, 1934).

Claudette Colbert . Italian postcard by Rizzoli, Milano, 1937. Photo: Columbia.

Ronald Colman and Jane Wyatt. Italian postcard by Vecchioni & Guadagno, Roma. Photo: Columbia EIA. Publicity still for Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937).

Marie McDonald. Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia.

Sonja Henie . Dutch Postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia F.B. / M.P.E.

Hollywood's Siberia for the less obedient stars

Columbia could not afford to keep a huge roster of contract stars, so Cohn usually borrowed them from other studios. At Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the industry's most prestigious studio, Columbia was nicknamed 'Siberia, as Louis B. Mayer would use the loan out to Columbia as a way to punish his less-obedient signings. In the 1930s, Columbia signed Jean Arthur to a long-term contract, and after The Whole Town's Talking (John Ford, 1935), Arthur became a major comedy star. Ann Sothern's career was launched when Columbia signed her to a contract in 1936. Cary Grant signed a contract in 1937 and soon after it was altered to a non-exclusive contract shared with RKO.

Many theatres relied on Westerns to attract big weekend audiences, and Columbia always recognised this market. Its first cowboy star was Buck Jones, who signed with Columbia in 1930 for a fraction of his former big-studio salary. Over the next two decades Columbia released scores of outdoor adventures with Jones, Tim McCoy, Ken Maynard, Robert (Tex) Allen, and Gene Autry. Columbia's most popular cowboy was Charles Starrett, who signed with Columbia in 1935 and starred in 131 western features over 17 years.

At Harry Cohn's insistence the studio signed The Three Stooges in 1934. MGM had let the Stooges go but kept straight-man Ted Healy. The Stooges made 190 shorts for Columbia between 1934 and 1957. Columbia's short-subject department employed many famous comedians, including Buster Keaton , Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and Hugh Herbert. Almost 400 of Columbia's 529 two-reel comedies were released to television between 1958 and 1961; and have since been released to home video.

In the early 1930s, Columbia distributed Walt Disney's famous Mickey Mouse cartoons. In 1933, the studio established its own animation house, under the Screen Gems brand. Columbia's leading cartoon series were Krazy Kat, Scrappy, The Fox and the Crow, and (very briefly) Li'l Abner. In 1949, Columbia agreed to release animated shorts from United Productions of America. These new shorts were more sophisticated than Columbia's older cartoons, and many won critical praise and industry awards.

According to Bob Thomas' book King Cohn, studio chief Harry Cohn always placed a high priority on serials. Beginning in 1937, Columbia entered the lucrative serial market, and kept making these episodic adventures until 1956, after other studios had discontinued them. The most famous Columbia serials are based on comic-strip or radio characters: Mandrake the Magician, The Shadow, Terry and the Pirates, Batman, and Superman, among many others.

Columbia also produced musical shorts, sports reels (usually narrated by sportscaster Bill Stern), and travelogues. Its 'Screen Snapshots' series, showing behind-the-scenes footage of Hollywood stars, was a Columbia perennial; producer-director Ralph Staub kept this series going through 1958.

Merle Oberon . Italian postcard by Rotalfoto, Milano, no. 46. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Burt Lancaster . Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 957. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Marta Toren . Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 3048. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Vittorio Gassman . Italian postcard by Casa Editr. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F. Edit.), no. 2962. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

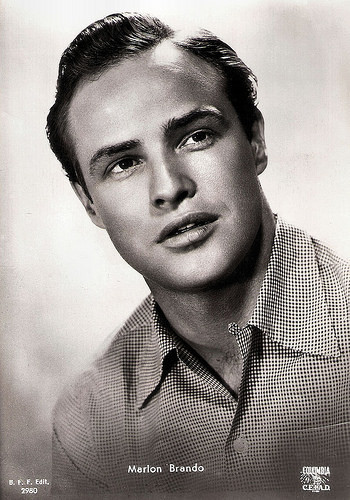

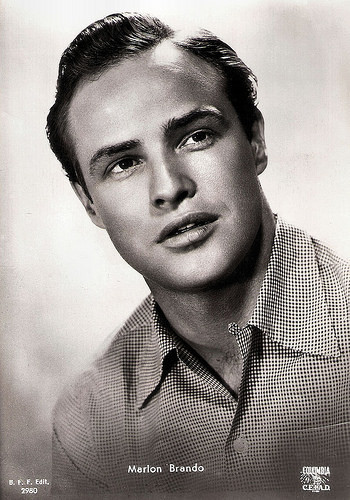

Marlon Brando . Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 2980. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Columbia's efficient recycling policy

In the 1940s, Columbia propelled in part by their film's surge in audiences during the war, and also benefited from the popularity of its biggest star, Rita Hayworth . Columbia maintained a long list of contractees well into the 1950s: Glenn Ford, William Holden, Judy Holliday, The Three Stooges, Ann Miller, Jack Lemmon, Adele Jergens, Lucille Ball, Kerwin Mathews, Kim Novak , and others.

Harry Cohn monitored the budgets of his films, and the studio got the maximum use out of costly sets, costumes, and props by reusing them in other films. Many of Columbia's low-budget B-films and short subjects have an expensive look, thanks to Columbia's efficient recycling policy. Cohn was reluctant to spend lavish sums on even his most important pictures, and it was not until 1943 that he agreed to use three-strip Technicolor in a live-action feature.

Columbia's first Technicolor feature was the Western The Desperadoes, starring Randolph Scott and Glenn Ford. Cohn quickly used Technicolor again for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944), a Hayworth vehicle that instantly was a smash hit, and for the fanciful biography of Frédéric Chopin, A Song to Remember (Charles Vidor, 1945), with Cornel Wilde and Merle Oberon . Another biopic, The Jolson Story (Alfred E. Green, 1946) with Larry Parks, was started in black-and-white, but when Cohn saw how well the project was proceeding, he scrapped the footage and insisted on filming in Technicolor.

In 1948, the United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. anti-trust decision forced Hollywood motion picture companies to divest themselves of the theatre chains that they owned. Since Columbia did not own any theatres, it was now on equal terms with the largest studios, and soon replaced RKO on the list of the Big Five studios.

By 1950, Columbia had discontinued most of its popular series films like Boston Blackie, Blondie, The Lone Wolf, etc. Only Jungle Jim featuring Johnny Weissmuller , launched by producer Sam Katzman in 1949, kept going through 1955. Katzman contributed greatly to Columbia's success by producing dozens of topical feature films, including crime dramas, Science-Fiction stories, and Rock-'n'-Roll musicals. Columbia kept making serials until 1956 and two-reel comedies until 1957, after other studios had abandoned them.

Rita Hayworth . Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 284.

Rita Hayworth . Dutch postcard, Col. Int., no. 286. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944).

Rita Hayworth . Spanish postcard, no. 4026. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946).

Rita Hayworth . Vintage card by IBIS, no. 23. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946). Costume by Jean Louis.

Rita Hayworth . German postcard by F.J. Rüdel Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 423. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Affair in Trinidad (Vincent Sherman, 1952).

Backing independent producers and directors

As the larger studios declined in the 1950s, Columbia's position improved. This was largely because it did not suffer from the massive loss of income that the other major studios suffered from losing their theatres. Columbia backed various independent producers and directors, among them Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, David Lean, Robert Rossen, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Losey.

The studio continued to produce 40-plus pictures a year, offering productions that often broke ground and kept audiences coming to cinemas such as its adaptation of the controversial James Jones novel, From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953) with Burt Lancaster , On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) with Marlon Brando , and The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957) with William Holden, Jack Hawkins and Alec Guinness . All three films won the Best Picture Oscar.

Columbia president Harry Cohn died of a heart attack in February 1958. By 1966, the studio was suffering from box-office failures, and takeover rumours began surfacing. After turning down releasing Albert R. Broccoli's Eon Productions James Bond films, Columbia had hired Broccoli's former partner Irving Allen to produce the Matt Helm series with Dean Martin. Columbia also produced a James Bond spoof, Casino Royale (Val Guest, a.o., 1967), in conjunction with Charles K. Feldman, which held the adaptation rights for that novel. The studio also offered old-fashioned fare like A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966) and Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968).

Columbia came back with the more contemporary Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) with Peter Fonda, Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970) starring Jack Nicholson, and The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971). During the 1970s, the studio re-emerged with hits like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), Tootsie (Sydney Pollack, 1982), and Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1982). Columbia was purchased by The Coca-Cola Company in 1982. That same year, Columbia helped launch a new motion-picture studio, Tri-Star Pictures, which was merged with Columbia in 1987 to form Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc. In 1989 Columbia was acquired by the Sony Corporation of Japan.

The Columbia Pictures logo, featuring a woman carrying a torch and wearing a drape (representing Columbia, a personification of the United States), has gone through five major revisions. Originally in 1924, Columbia Pictures used a logo featuring a female Roman soldier holding a shield in her left hand and a stick of wheat in her right hand. The logo changed in 1928 with the woman wearing a draped flag and torch. The woman wore the stole and carried the palla of ancient Rome, and above her were the words A Columbia Production. The current logo was created in 1992, when Scott Mednick was hired by Peter Guber to create logos for all the entertainment properties then owned by Sony Pictures. Mednick hired New Orleans artist Michael Deas, to digitally repaint the logo and return the woman to her a classic look.

Maureen O'Hara . Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam, no. 2028. Photo: Columbia Film / Ufa.

Gloria Grahame . German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 032. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane, 1953).

Ursula Thiess . German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1240. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Iron Glove (William Castle, 1954).

Jack Hawkins . Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 8304. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957).

Jean Seberg . German postcard by WS-Druck, Wanne-Eickel, no. 334. Photo: Columbia / Filmpress Zürich.

Sources: Aurora (Once upon a screen), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Rita Hayworth . Belgian postcard by Victoria, Brussels, no. 639. Photo: Columbia Pictures.

Cary Grant. British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 735c. Photo: Columbia.

Adele Jergens. British postcard in Picturegoer Series, London, no. W 643. Photo: Columbia.

Claudette Colbert . Dutch postcard by J.S.A.. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Tomorrow is Forever (Irving Pichel, 1946).

Burt Lancaster . German postcard by Franz Josef Rüdel, Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 858. Photo: Columbia-Film. Publicity still for From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953).

The Corned Beef and Cabbage Studio

Columbia was founded in June 1918 as Cohn-Brandt-Cohn (CBC) Film Sales by brothers Jack and Harry Cohn and Jack's best friend Joe Brandt. Jack had worked for Carl Laemmle at Universal, Joe had been Laemmle’s executive secretary and Jack’s younger brother Harry, had also worked at Universal.They released their first feature film in August 1922. Brandt was president of CBC Film Sales, handling sales, marketing and distribution from New York along with Jack Cohn, while Harry Cohn ran production in Hollywood.

The studio's early productions were low-budget short subjects: 'Screen Snapshots', the 'Hall Room Boys' (the vaudeville duo of Edward Flanagan and Neely Edwards), and the Chaplin imitator Billy West. The start-up CBC leased space in a Poverty Row studio on Hollywood's famously low-rent Gower Street. Among Hollywood's elite, the studio's small-time reputation led some to joke that CBC stood for 'Corned Beef and Cabbage'. Brandt eventually tired of dealing with the Cohn brothers, and he sold his one-third stake to Harry Cohn, who took over as president.

In an effort to improve its image, the Cohn brothers renamed the company Columbia Pictures Corporation in 1924. Cohn remained head of production as well, thus concentrating enormous power in his hands. He would run Columbia for the next 34 years, the second-longest tenure of any studio chief, behind only Warner Bros.' Jack L. Warner. Even in an industry rife with nepotism, Columbia was particularly notorious for having a number of Harry and Jack's relatives in high positions. Humorist Robert Benchley called it the Pine Tree Studio, "because it has so many Cohns".

Columbia's product line consisted mostly of moderately budgeted features and short subjects including comedies, sports films, various serials, and cartoons. Columbia gradually moved into the production of higher-budget fare, eventually joining the second tier of Hollywood studios along with United Artists and Universal. Like United Artists and Universal, Columbia was a horizontally integrated company. It controlled production and distribution; it did not own any theatres.

Helping Columbia's climb was the arrival of an ambitious director, Frank Capra. Between 1927 and 1939, Capra constantly pushed Cohn for better material and bigger budgets. A string of hits he directed in the early and mid 1930s solidified Columbia's status as a major studio. In particular, It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934) with Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert put Columbia on the map. It won the Academy Award for Best Film of 1934.

Until then, Columbia's very existence had depended on theatre owners willing to take its films, since as mentioned above it didn't have a theatre network of its own. Other Capra-directed hits followed, including Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (Frank Capra, 1936), the original version of Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937) with Ronald Colman , You Can’t Take it With You (Frank Capra, 1938), which was Capra's highest-grossing picture at Columbia, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939), which made James Stewart a major star.

Capra but also Howard Hawks and others made some of the finest screwball comedies of the 1930s for Columbia: The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937), Holiday (George Cukor, 1938), and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940), all starring Cary Grant. After Capra’s departure in 1939, Columbia languished because leading directors were reluctant to work for the notoriously hard-driving and vulgar Cohn.

In 1938, the addition of B. B. Kahane as Vice President would produce Charles Vidor's Those High Gray Walls (Charles Vidor, 1939), and The Lady in Question (Charles Vidor, 1940), the first joint film of Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford. Kahane would later become the President of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1959, until his death a year later.

Tullio Carminati and Grace Moore. British postcard in the Film Partners Series, London, no. P 151. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for One Night of Love (Victor Schertzinger, 1934).

Claudette Colbert . Italian postcard by Rizzoli, Milano, 1937. Photo: Columbia.

Ronald Colman and Jane Wyatt. Italian postcard by Vecchioni & Guadagno, Roma. Photo: Columbia EIA. Publicity still for Lost Horizon (Frank Capra, 1937).

Marie McDonald. Dutch postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia.

Sonja Henie . Dutch Postcard by J.S.A. Photo: Columbia F.B. / M.P.E.

Hollywood's Siberia for the less obedient stars

Columbia could not afford to keep a huge roster of contract stars, so Cohn usually borrowed them from other studios. At Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the industry's most prestigious studio, Columbia was nicknamed 'Siberia, as Louis B. Mayer would use the loan out to Columbia as a way to punish his less-obedient signings. In the 1930s, Columbia signed Jean Arthur to a long-term contract, and after The Whole Town's Talking (John Ford, 1935), Arthur became a major comedy star. Ann Sothern's career was launched when Columbia signed her to a contract in 1936. Cary Grant signed a contract in 1937 and soon after it was altered to a non-exclusive contract shared with RKO.

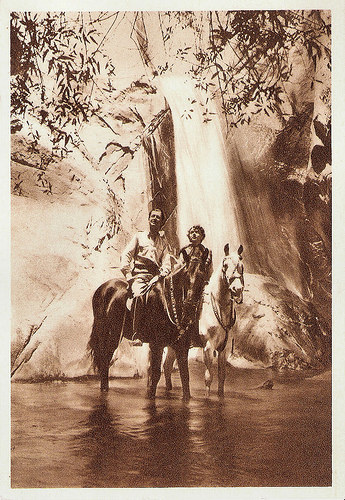

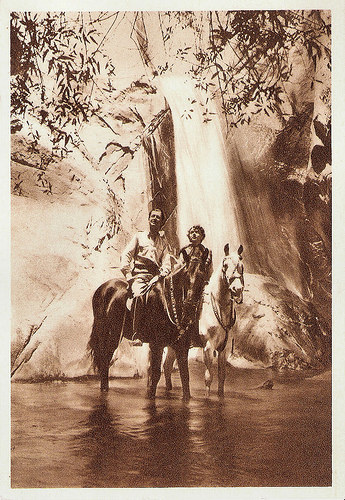

Many theatres relied on Westerns to attract big weekend audiences, and Columbia always recognised this market. Its first cowboy star was Buck Jones, who signed with Columbia in 1930 for a fraction of his former big-studio salary. Over the next two decades Columbia released scores of outdoor adventures with Jones, Tim McCoy, Ken Maynard, Robert (Tex) Allen, and Gene Autry. Columbia's most popular cowboy was Charles Starrett, who signed with Columbia in 1935 and starred in 131 western features over 17 years.

At Harry Cohn's insistence the studio signed The Three Stooges in 1934. MGM had let the Stooges go but kept straight-man Ted Healy. The Stooges made 190 shorts for Columbia between 1934 and 1957. Columbia's short-subject department employed many famous comedians, including Buster Keaton , Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and Hugh Herbert. Almost 400 of Columbia's 529 two-reel comedies were released to television between 1958 and 1961; and have since been released to home video.

In the early 1930s, Columbia distributed Walt Disney's famous Mickey Mouse cartoons. In 1933, the studio established its own animation house, under the Screen Gems brand. Columbia's leading cartoon series were Krazy Kat, Scrappy, The Fox and the Crow, and (very briefly) Li'l Abner. In 1949, Columbia agreed to release animated shorts from United Productions of America. These new shorts were more sophisticated than Columbia's older cartoons, and many won critical praise and industry awards.

According to Bob Thomas' book King Cohn, studio chief Harry Cohn always placed a high priority on serials. Beginning in 1937, Columbia entered the lucrative serial market, and kept making these episodic adventures until 1956, after other studios had discontinued them. The most famous Columbia serials are based on comic-strip or radio characters: Mandrake the Magician, The Shadow, Terry and the Pirates, Batman, and Superman, among many others.

Columbia also produced musical shorts, sports reels (usually narrated by sportscaster Bill Stern), and travelogues. Its 'Screen Snapshots' series, showing behind-the-scenes footage of Hollywood stars, was a Columbia perennial; producer-director Ralph Staub kept this series going through 1958.

Merle Oberon . Italian postcard by Rotalfoto, Milano, no. 46. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Burt Lancaster . Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 957. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Marta Toren . Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 3048. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Vittorio Gassman . Italian postcard by Casa Editr. Ballerini & Fratini, Firenze (B.F.F. Edit.), no. 2962. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Marlon Brando . Italian postcard by B.F.F. Edit., no. 2980. Photo: Columbia C.E.I.A.D.

Columbia's efficient recycling policy

In the 1940s, Columbia propelled in part by their film's surge in audiences during the war, and also benefited from the popularity of its biggest star, Rita Hayworth . Columbia maintained a long list of contractees well into the 1950s: Glenn Ford, William Holden, Judy Holliday, The Three Stooges, Ann Miller, Jack Lemmon, Adele Jergens, Lucille Ball, Kerwin Mathews, Kim Novak , and others.

Harry Cohn monitored the budgets of his films, and the studio got the maximum use out of costly sets, costumes, and props by reusing them in other films. Many of Columbia's low-budget B-films and short subjects have an expensive look, thanks to Columbia's efficient recycling policy. Cohn was reluctant to spend lavish sums on even his most important pictures, and it was not until 1943 that he agreed to use three-strip Technicolor in a live-action feature.

Columbia's first Technicolor feature was the Western The Desperadoes, starring Randolph Scott and Glenn Ford. Cohn quickly used Technicolor again for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944), a Hayworth vehicle that instantly was a smash hit, and for the fanciful biography of Frédéric Chopin, A Song to Remember (Charles Vidor, 1945), with Cornel Wilde and Merle Oberon . Another biopic, The Jolson Story (Alfred E. Green, 1946) with Larry Parks, was started in black-and-white, but when Cohn saw how well the project was proceeding, he scrapped the footage and insisted on filming in Technicolor.

In 1948, the United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. anti-trust decision forced Hollywood motion picture companies to divest themselves of the theatre chains that they owned. Since Columbia did not own any theatres, it was now on equal terms with the largest studios, and soon replaced RKO on the list of the Big Five studios.

By 1950, Columbia had discontinued most of its popular series films like Boston Blackie, Blondie, The Lone Wolf, etc. Only Jungle Jim featuring Johnny Weissmuller , launched by producer Sam Katzman in 1949, kept going through 1955. Katzman contributed greatly to Columbia's success by producing dozens of topical feature films, including crime dramas, Science-Fiction stories, and Rock-'n'-Roll musicals. Columbia kept making serials until 1956 and two-reel comedies until 1957, after other studios had abandoned them.

Rita Hayworth . Italian postcard by Bromofoto, no. 284.

Rita Hayworth . Dutch postcard, Col. Int., no. 286. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Cover Girl (Charles Vidor, 1944).

Rita Hayworth . Spanish postcard, no. 4026. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946).

Rita Hayworth . Vintage card by IBIS, no. 23. Photo: Robert Coburn / Columbia Pictures. Publicity still for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946). Costume by Jean Louis.

Rita Hayworth . German postcard by F.J. Rüdel Filmpostkartenverlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 423. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for Affair in Trinidad (Vincent Sherman, 1952).

Backing independent producers and directors

As the larger studios declined in the 1950s, Columbia's position improved. This was largely because it did not suffer from the massive loss of income that the other major studios suffered from losing their theatres. Columbia backed various independent producers and directors, among them Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, David Lean, Robert Rossen, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Losey.

The studio continued to produce 40-plus pictures a year, offering productions that often broke ground and kept audiences coming to cinemas such as its adaptation of the controversial James Jones novel, From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953) with Burt Lancaster , On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954) with Marlon Brando , and The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957) with William Holden, Jack Hawkins and Alec Guinness . All three films won the Best Picture Oscar.

Columbia president Harry Cohn died of a heart attack in February 1958. By 1966, the studio was suffering from box-office failures, and takeover rumours began surfacing. After turning down releasing Albert R. Broccoli's Eon Productions James Bond films, Columbia had hired Broccoli's former partner Irving Allen to produce the Matt Helm series with Dean Martin. Columbia also produced a James Bond spoof, Casino Royale (Val Guest, a.o., 1967), in conjunction with Charles K. Feldman, which held the adaptation rights for that novel. The studio also offered old-fashioned fare like A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966) and Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968).

Columbia came back with the more contemporary Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) with Peter Fonda, Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970) starring Jack Nicholson, and The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971). During the 1970s, the studio re-emerged with hits like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), Tootsie (Sydney Pollack, 1982), and Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1982). Columbia was purchased by The Coca-Cola Company in 1982. That same year, Columbia helped launch a new motion-picture studio, Tri-Star Pictures, which was merged with Columbia in 1987 to form Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc. In 1989 Columbia was acquired by the Sony Corporation of Japan.

The Columbia Pictures logo, featuring a woman carrying a torch and wearing a drape (representing Columbia, a personification of the United States), has gone through five major revisions. Originally in 1924, Columbia Pictures used a logo featuring a female Roman soldier holding a shield in her left hand and a stick of wheat in her right hand. The logo changed in 1928 with the woman wearing a draped flag and torch. The woman wore the stole and carried the palla of ancient Rome, and above her were the words A Columbia Production. The current logo was created in 1992, when Scott Mednick was hired by Peter Guber to create logos for all the entertainment properties then owned by Sony Pictures. Mednick hired New Orleans artist Michael Deas, to digitally repaint the logo and return the woman to her a classic look.

Maureen O'Hara . Dutch postcard by Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam, no. 2028. Photo: Columbia Film / Ufa.

Gloria Grahame . German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 032. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Glass Wall (Maxwell Shane, 1953).

Ursula Thiess . German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, no. 1240. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Iron Glove (William Castle, 1954).

Jack Hawkins . Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 8304. Photo: Columbia. Publicity still for The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957).

Jean Seberg . German postcard by WS-Druck, Wanne-Eickel, no. 334. Photo: Columbia / Filmpress Zürich.

Sources: Aurora (Once upon a screen), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Wikipedia and IMDb.

Published on November 30, 2018 22:00

November 29, 2018

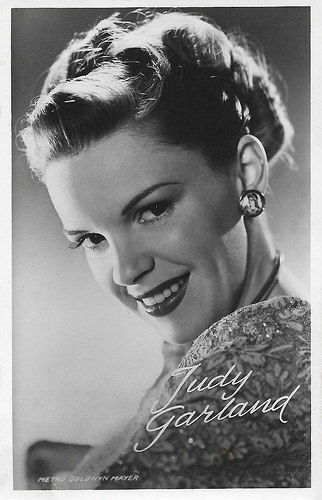

Judy Garland

American singer, actress, and vaudevillian Judy Garland (1922-1969) was one of the brightest, most tragic film stars of Hollywood's Golden Era. During a career that spanned 45 of her 47 years, Garland attained international stardom as an actress in musicals and dramas, with her records, and on the concert stage. She was nominated for the Oscar for Best Actress for A Star is Born (1954) and received a nomination for Best Supporting Actress for Judgment at Nuremberg (1961). With her warmth, spirit, and her rich and exuberant voice, Garland entertained devoted theatregoers with an array of musicals.

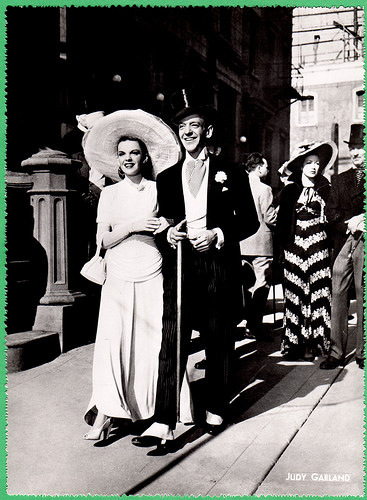

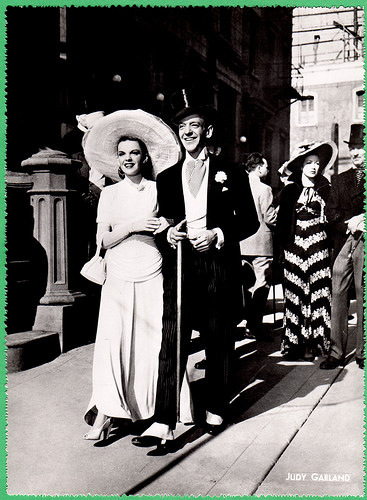

Belgian postcard by S.A. Victoria, Brussels, no. 639. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

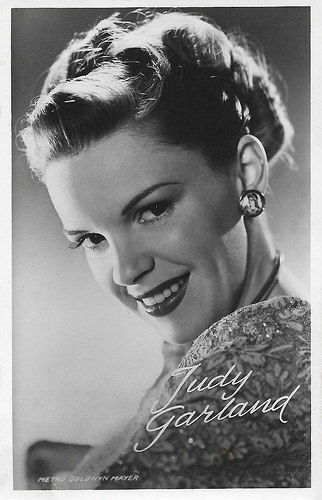

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 273. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1950.

An orphaned girl on a farm in the dry plains of Kansas

Judy Garland was born Frances Ethel Gumm in 1922 in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, U.S. She was the youngest daughter of vaudevillians Ethel Marion (Milne) and Francis Avent Gumm. Only two, Garland began performing in vaudeville with her two older sisters Mary Jane Gumm and Virginia Gumm as 'The Gumm Sisters'.

Her family life was not a happy one, largely because of her mother's drive for her to succeed as a performer and also her father's closeted homosexuality. The Gumm family would regularly be forced to leave town owing to her father's illicit affairs with other men, and from time to time they would be reduced to living out of their automobile.

Her mother took Frances out of the The Gumm Sisters act and together they travelled across America where she would perform in nightclubs, cabarets, hotels and theatres solo. In 1935, Frances was signed by Louis B. Mayer, mogul of leading film studio MGM, after hearing her sing. It was then that her name was changed from Frances Gumm to Judy Garland, after a popular 1930s song 'Judy' and film critic Robert Garland. Tragedy followed two months later, when her father died of meningitis in November 1935.

Having been given no assignments with the exception of singing on radio, Judy faced the threat of losing her job following the arrival of Deanna Durbin. Knowing that they couldn't keep both of the teenage singers, MGM devised a short entitled Every Sunday (Felix E. Feist, 1936) which would be the girls' screen test. Judy was the outright winner and MGM kept her. Durbin moved to Universal.

Judy's film debut was in Pigskin Parade (David Butler, 1936), in which she played a teenage hillbilly. Her career did officially kick off when she sang one of her most famous songs, 'You Made Me Love You', at Clark Gable's birthday party in February 1937. Louis B. Mayer finally paid attention to the talented songstress, and MGM set to work preparing various musicals with her.

All the work on these musicals took its toll on the young teenager, and she was given numerous pills by the studio doctors in order to combat her tiredness on set. Another problem was her weight fluctuation, but she was soon given amphetamines in order to give her the desired streamlined figure. This would produce the downward spiral that resulted in her lifelong drug addiction.

In 1939, Judy shot to stardom with The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), in which she portrayed Dorothy, an orphaned girl living on a farm in the dry plains of Kansas who gets whisked off into the magical world of Oz on the other end of the rainbow. Her poignant performance and sweet delivery of her signature song, 'Over The Rainbow', earned Judy a special juvenile Oscar statuette in 1940 for Best Performance by a Juvenile Actor.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London,, no. 1281. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Publicity still for Love Finds Andy Hardy (George B. Seitz, 1938) with Mickey Rooney, Ann Rutherford, Judy Garland and Lana Turner.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1178b. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Dutch postcard, no. 3114. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, Busby Berkeley, 1941) with Hedy Lamarr and Lana Turner.

A love affair between director and actress

Judy Garland was now taking an interest in men. After starring in her final juvenile performance in Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, Busby Berkeley, 1941) alongside glamorous beauties Lana Turner and Hedy Lamarr , Judy got engaged to bandleader David Rose in May 1941, just two months after his divorce from Martha Raye. Despite planning a big wedding, the couple eloped to Las Vegas and married with just her mother Ethel and her stepfather Will Gilmore present. However, their marriage went downhill as, after discovering that she was pregnant in November 1942, David and MGM persuaded her to abort the baby in order to keep her good-girl image up. She did so and, as a result, was haunted for the rest of her life by her 'inhumane actions'. The couple separated in January 1943.

Garland made more than two dozen films with MGM, nine of which with Mickey Rooney. She played a vaudevillian during WWI in For Me and My Gal (Busby Berkeley, 1942). A big success was Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincente Minnelli, 1944), Director Vincente Minnelli highlighted Judy's beauty for the first time on screen, having made the period musical in colour. He showed off her large brandy-brown eyes and her full, thick lips and after filming ended in April 1944, a love affair resulted between director and actress and they were soon living together.

Vincente began to mold Judy and her career, making her more beautiful and more popular with audiences worldwide. He directed her in The Clock (Vincente Minnelli, 1945), and during the filming the couple announced their engagement. On 15 June 1945 Judy and Vincente married at her mother's home with her boss Louis B. Mayer giving her away and her best friend Betty Asher serving as bridesmaid. After their honeymoon in New York, Judy discovered that she was pregnant. Her first film after marrying Vincente Minnelli was The Harvey Girls (Vincente Minnelli, 1946). Then Judy gave birth to their daughter, Liza Minnelli.

After a postnatal depression, she spent much of her time recuperating in bed. She returned to work, to film The Pirate (Vincente Minnelli, 1948) with Gene Kelly. Judy's mental health was deteriorating and she began hallucinating things and making false accusations toward people, especially her husband, making the filming a nightmare. She then teamed up with Fred Astaire for the musical Easter Parade (Charles Walters, 1948), which resulted in a successful comeback despite having Vincente fired from directing the musical.

Afterwards, Judy's health deteriorated and she began the first of several suicide attempts. In May 1949, she was checked into a rehabilitation center, which caused her much distress. After being replaced by Betty Hutton on Annie Get Your Gun (George Sidney, 1950), Judy was suspended before making her final film for MGM, Summer Stock (Charles Walters, 1950). Then Judy received her third suspension and was fired by MGM, and her second marriage was also soon dissolved.

Having taken up with ruggedly handsome and streetwise entrepreneur Sidney Luft, Judy travelled to London to star at the legendary Palladium. She was an instant success and after her divorce to Vincente Minnelli was finalised on 29 March 1951 after almost six years of marriage, Judy travelled with Sid to New York to make an appearance on Broadway. With her new found fame on stage, Judy was stopped in her tracks in February 1952 when she became pregnant by Sid Luft. At the age of 30, she made him her third husband.

Her relationship with her mother had long since been dissolved by this point, and after the birth of her second daughter, Lorna Luft, on 21 November 1952, she refused to allow her mother to see her granddaughter. Ethel then died in January 1953 of a heart attack, leaving Judy devastated and feeling guilty about not reconciling with her mother before her untimely demise.

Belgian collectors card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer. Publicity still for Easter Parade (Charles Walters, 1948) with Fred Astaire. Collection: Amit Benyovits.

Dutch postcard, no. 3371. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

A volatile, on-off relationship resulting in numerous divorce filings

Judy Garland was released from MGM in 1950, amid a series of personal struggles and erratic behaviour that had prevented her from fulfilling the terms of her contract. She signed a new film contract with Warner Bros. to star in the musical remake of A Star is Born (William A. Wellman, 1937), which had starred Janet Gaynor . After filming was complete Judy was yet again lauded as a great film star. She won a Golden Globe for her brilliant and outstanding performance as nightclub singer Esther Blodgett who turns into film star Vicki Lester. But she lost out on the Best Actress Oscar to Grace Kelly for her portrayal of the wife of an alcoholic star in The Country Girl (George Seaton, 1954).

Continuing her work on stage, Judy gave birth to son Joey Luft in 1955. She soon began to lose her millions of dollars as a result of her husband's strong gambling addiction. With hundreds of debts to pay, Judy and Sid began a volatile, on-off relationship resulting in numerous divorce filings. In 1961, at the age of 39, Judy returned to her ailing film career, this time to star in Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961). She received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, but this time she lost out to Rita Moreno for her role in West Side Story (Robert Wise, 1961).

Her battles with alcoholism and drugs led to Judy's making headlines in newspapers, but she soldiered on. She made record-breaking concert appearances, released eight studio albums, and hosted her own Emmy-nominated television series, The Judy Garland Show (1963–1964). In 1965, Judy and Sid finally divorced after almost 13 years of marriage. By this time, Judy, now 41, had made her final film performance alongside Dirk Bogarde in I Could Go on Singing (Ronald Neame, 1963).

She married her fourth husband, Mark Herron, in 1965 in Las Vegas. The couple separated in April 1966 after five months of marriage, owing to his homosexuality. She then settled down in London, and she began dating disk jockey Mickey Deans in December 1968. They became engaged once her divorce from Mark Herron was finalised on 9 January 1969 after three years of marriage. She married Mickey, her fifth and final husband, in Chelsea, London.

Judy Garland continued working on stage, appearing several times with her daughter Liza. It was during a concert in Chelsea, London, that Judy stumbled into her bathroom late one night and died of an accidental overdose of barbiturates, on the 22nd of June 1969 at the age of 47. The day she died, there was a tornado in Kansas.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1280. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Publicity still for Love Finds Andy Hardy (George B. Seitz, 1938) with (back row) Cecilia Parker, Ann Rutherford, Judy Garland, Gene Reynolds, Lana Turner and (front row) Mary Howard, Lewis Stone, Fay Holden and Mickey Rooney.

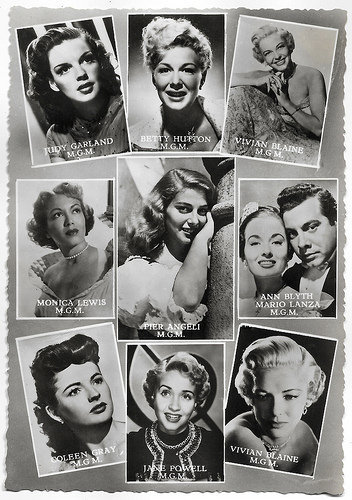

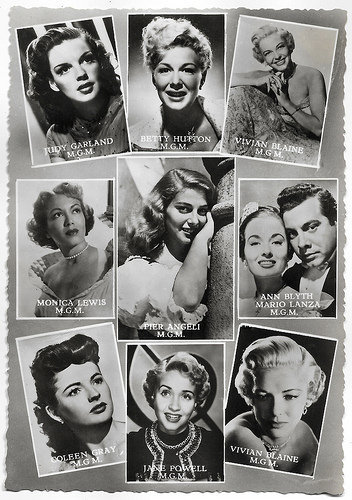

Dutch postcard by Sparo (Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam). Photos: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The pictures stars are Judy Garland, Betty Hutton, Vivian Blaine (twice), Monica Lewis, Pier Angeli , Ann Blyth and Mario Lanza, Coleen Gray, and Jane Powell. The postcard must date from ca. 1951, when Blyth and Lanza starred together in The Great Caruso (Richard Thorpe, 1951).

Sources: Wikipedia and .

Belgian postcard by S.A. Victoria, Brussels, no. 639. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. 273. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1950.

An orphaned girl on a farm in the dry plains of Kansas

Judy Garland was born Frances Ethel Gumm in 1922 in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, U.S. She was the youngest daughter of vaudevillians Ethel Marion (Milne) and Francis Avent Gumm. Only two, Garland began performing in vaudeville with her two older sisters Mary Jane Gumm and Virginia Gumm as 'The Gumm Sisters'.

Her family life was not a happy one, largely because of her mother's drive for her to succeed as a performer and also her father's closeted homosexuality. The Gumm family would regularly be forced to leave town owing to her father's illicit affairs with other men, and from time to time they would be reduced to living out of their automobile.

Her mother took Frances out of the The Gumm Sisters act and together they travelled across America where she would perform in nightclubs, cabarets, hotels and theatres solo. In 1935, Frances was signed by Louis B. Mayer, mogul of leading film studio MGM, after hearing her sing. It was then that her name was changed from Frances Gumm to Judy Garland, after a popular 1930s song 'Judy' and film critic Robert Garland. Tragedy followed two months later, when her father died of meningitis in November 1935.

Having been given no assignments with the exception of singing on radio, Judy faced the threat of losing her job following the arrival of Deanna Durbin. Knowing that they couldn't keep both of the teenage singers, MGM devised a short entitled Every Sunday (Felix E. Feist, 1936) which would be the girls' screen test. Judy was the outright winner and MGM kept her. Durbin moved to Universal.

Judy's film debut was in Pigskin Parade (David Butler, 1936), in which she played a teenage hillbilly. Her career did officially kick off when she sang one of her most famous songs, 'You Made Me Love You', at Clark Gable's birthday party in February 1937. Louis B. Mayer finally paid attention to the talented songstress, and MGM set to work preparing various musicals with her.

All the work on these musicals took its toll on the young teenager, and she was given numerous pills by the studio doctors in order to combat her tiredness on set. Another problem was her weight fluctuation, but she was soon given amphetamines in order to give her the desired streamlined figure. This would produce the downward spiral that resulted in her lifelong drug addiction.

In 1939, Judy shot to stardom with The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), in which she portrayed Dorothy, an orphaned girl living on a farm in the dry plains of Kansas who gets whisked off into the magical world of Oz on the other end of the rainbow. Her poignant performance and sweet delivery of her signature song, 'Over The Rainbow', earned Judy a special juvenile Oscar statuette in 1940 for Best Performance by a Juvenile Actor.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London,, no. 1281. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Publicity still for Love Finds Andy Hardy (George B. Seitz, 1938) with Mickey Rooney, Ann Rutherford, Judy Garland and Lana Turner.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1178b. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Dutch postcard, no. 3114. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, Busby Berkeley, 1941) with Hedy Lamarr and Lana Turner.

A love affair between director and actress

Judy Garland was now taking an interest in men. After starring in her final juvenile performance in Ziegfeld Girl (Robert Z. Leonard, Busby Berkeley, 1941) alongside glamorous beauties Lana Turner and Hedy Lamarr , Judy got engaged to bandleader David Rose in May 1941, just two months after his divorce from Martha Raye. Despite planning a big wedding, the couple eloped to Las Vegas and married with just her mother Ethel and her stepfather Will Gilmore present. However, their marriage went downhill as, after discovering that she was pregnant in November 1942, David and MGM persuaded her to abort the baby in order to keep her good-girl image up. She did so and, as a result, was haunted for the rest of her life by her 'inhumane actions'. The couple separated in January 1943.

Garland made more than two dozen films with MGM, nine of which with Mickey Rooney. She played a vaudevillian during WWI in For Me and My Gal (Busby Berkeley, 1942). A big success was Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincente Minnelli, 1944), Director Vincente Minnelli highlighted Judy's beauty for the first time on screen, having made the period musical in colour. He showed off her large brandy-brown eyes and her full, thick lips and after filming ended in April 1944, a love affair resulted between director and actress and they were soon living together.

Vincente began to mold Judy and her career, making her more beautiful and more popular with audiences worldwide. He directed her in The Clock (Vincente Minnelli, 1945), and during the filming the couple announced their engagement. On 15 June 1945 Judy and Vincente married at her mother's home with her boss Louis B. Mayer giving her away and her best friend Betty Asher serving as bridesmaid. After their honeymoon in New York, Judy discovered that she was pregnant. Her first film after marrying Vincente Minnelli was The Harvey Girls (Vincente Minnelli, 1946). Then Judy gave birth to their daughter, Liza Minnelli.

After a postnatal depression, she spent much of her time recuperating in bed. She returned to work, to film The Pirate (Vincente Minnelli, 1948) with Gene Kelly. Judy's mental health was deteriorating and she began hallucinating things and making false accusations toward people, especially her husband, making the filming a nightmare. She then teamed up with Fred Astaire for the musical Easter Parade (Charles Walters, 1948), which resulted in a successful comeback despite having Vincente fired from directing the musical.

Afterwards, Judy's health deteriorated and she began the first of several suicide attempts. In May 1949, she was checked into a rehabilitation center, which caused her much distress. After being replaced by Betty Hutton on Annie Get Your Gun (George Sidney, 1950), Judy was suspended before making her final film for MGM, Summer Stock (Charles Walters, 1950). Then Judy received her third suspension and was fired by MGM, and her second marriage was also soon dissolved.

Having taken up with ruggedly handsome and streetwise entrepreneur Sidney Luft, Judy travelled to London to star at the legendary Palladium. She was an instant success and after her divorce to Vincente Minnelli was finalised on 29 March 1951 after almost six years of marriage, Judy travelled with Sid to New York to make an appearance on Broadway. With her new found fame on stage, Judy was stopped in her tracks in February 1952 when she became pregnant by Sid Luft. At the age of 30, she made him her third husband.

Her relationship with her mother had long since been dissolved by this point, and after the birth of her second daughter, Lorna Luft, on 21 November 1952, she refused to allow her mother to see her granddaughter. Ethel then died in January 1953 of a heart attack, leaving Judy devastated and feeling guilty about not reconciling with her mother before her untimely demise.

Belgian collectors card by Chocolaterie Clovis, Pepinster. Photo: Metro Goldwyn Mayer. Publicity still for Easter Parade (Charles Walters, 1948) with Fred Astaire. Collection: Amit Benyovits.

Dutch postcard, no. 3371. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

A volatile, on-off relationship resulting in numerous divorce filings

Judy Garland was released from MGM in 1950, amid a series of personal struggles and erratic behaviour that had prevented her from fulfilling the terms of her contract. She signed a new film contract with Warner Bros. to star in the musical remake of A Star is Born (William A. Wellman, 1937), which had starred Janet Gaynor . After filming was complete Judy was yet again lauded as a great film star. She won a Golden Globe for her brilliant and outstanding performance as nightclub singer Esther Blodgett who turns into film star Vicki Lester. But she lost out on the Best Actress Oscar to Grace Kelly for her portrayal of the wife of an alcoholic star in The Country Girl (George Seaton, 1954).

Continuing her work on stage, Judy gave birth to son Joey Luft in 1955. She soon began to lose her millions of dollars as a result of her husband's strong gambling addiction. With hundreds of debts to pay, Judy and Sid began a volatile, on-off relationship resulting in numerous divorce filings. In 1961, at the age of 39, Judy returned to her ailing film career, this time to star in Judgment at Nuremberg (Stanley Kramer, 1961). She received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, but this time she lost out to Rita Moreno for her role in West Side Story (Robert Wise, 1961).

Her battles with alcoholism and drugs led to Judy's making headlines in newspapers, but she soldiered on. She made record-breaking concert appearances, released eight studio albums, and hosted her own Emmy-nominated television series, The Judy Garland Show (1963–1964). In 1965, Judy and Sid finally divorced after almost 13 years of marriage. By this time, Judy, now 41, had made her final film performance alongside Dirk Bogarde in I Could Go on Singing (Ronald Neame, 1963).

She married her fourth husband, Mark Herron, in 1965 in Las Vegas. The couple separated in April 1966 after five months of marriage, owing to his homosexuality. She then settled down in London, and she began dating disk jockey Mickey Deans in December 1968. They became engaged once her divorce from Mark Herron was finalised on 9 January 1969 after three years of marriage. She married Mickey, her fifth and final husband, in Chelsea, London.

Judy Garland continued working on stage, appearing several times with her daughter Liza. It was during a concert in Chelsea, London, that Judy stumbled into her bathroom late one night and died of an accidental overdose of barbiturates, on the 22nd of June 1969 at the age of 47. The day she died, there was a tornado in Kansas.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 1280. Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Publicity still for Love Finds Andy Hardy (George B. Seitz, 1938) with (back row) Cecilia Parker, Ann Rutherford, Judy Garland, Gene Reynolds, Lana Turner and (front row) Mary Howard, Lewis Stone, Fay Holden and Mickey Rooney.

Dutch postcard by Sparo (Gebr. Spanjersberg N.V., Rotterdam). Photos: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The pictures stars are Judy Garland, Betty Hutton, Vivian Blaine (twice), Monica Lewis, Pier Angeli , Ann Blyth and Mario Lanza, Coleen Gray, and Jane Powell. The postcard must date from ca. 1951, when Blyth and Lanza starred together in The Great Caruso (Richard Thorpe, 1951).

Sources: Wikipedia and .

Published on November 29, 2018 22:00

November 28, 2018

Cleopatra (1934)

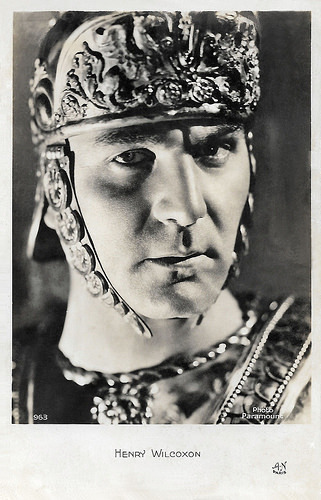

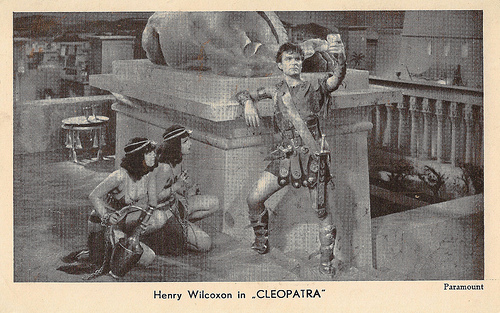

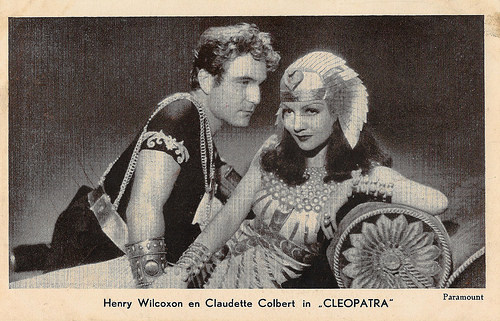

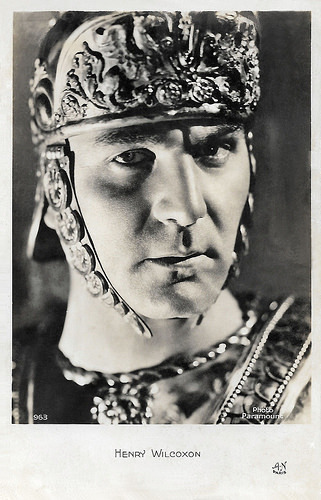

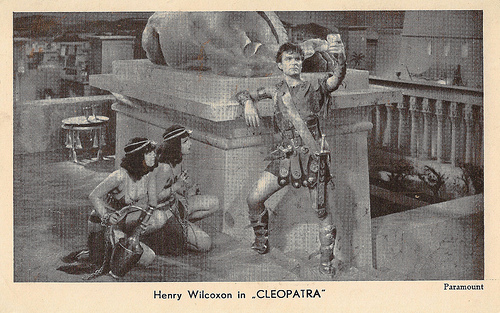

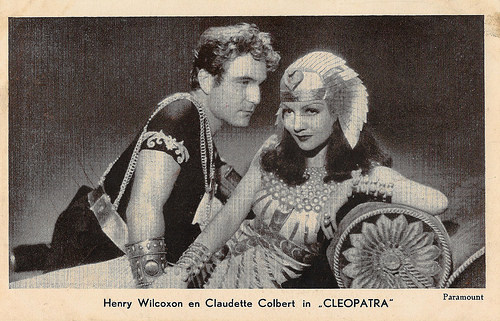

After his historical epic Sign of the Cross (1932), Cecil B. DeMille directed another ancient spectacle, Cleopatra (1934). His new star Claudette Colbert, fresh from her donkey milk bath in Sign of The Cross, played the politically shrewd, man-hungry queen of Egypt. In 48 BC, Cleopatra, facing palace revolt, welcomes the arrival of Julius Caesar (Warren William) as a way of solidifying her power under Rome. When Caesar, whom she has led astray, is killed, she transfers her affections to Marc Antony (Henry Wilcoxon) and dazzles him on a lavish barge. The film got five Oscar nominations, including one for Best Picture, and Victor Milner won the award for Best Cinematography.

Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony and Gertrude Michael as Caesar's wife Calpurnia. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 961. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. deMille, 1934).

Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra and Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 962. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Henri Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 963. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Warren William as Julius Caesar. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 965. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Deadly and fascinating

Wikipedia : "On July 1, 1934, the Motion Picture Production Code began to be rigidly enforced and expanded by Joseph Breen had just taken effect. Talkie films made before that date are generally referred to as Pre-Code films. However, DeMille was able to get away with using more risque imagery than he would be able to do in his later productions. He opens the film with an apparently naked, but strategically lit slave girl holding up an incense burner in each hand as the title appears on screen."

Ron Oliver at IMDb : "Claudette Colbert is perfectly cast in the title role - deadly & fascinating, it's almost like watching a desert viper act. Exhibiting mega star wattage in arguably her best role, Colbert is one of the legendary actresses who could hold her own without being swallowed by the lavish costumes & sets which fill her every scene."

John O'Grady at IMDb : "Colbert is admittedly somewhat miscast (her face is altogether Parisienne), but she handles the part with considerable charm. Warren William, usually a very limited actor, is as good a Caesar as I have seen on film, commanding and uncomfortable by turns; while Henry Wilcoxon is the definitive Mark Antony, laughing, brawling, swaggering, crude and brooding. C. Aubrey Smith as Enobarbus, the last of the hardcore Roman republicans, is perfect. Victor Milner's cinematography is superb, if old-fashioned. There is one magnificent pullback shot aboard Cleopatra's barge, with more and more stuff entering the frame, which as pure cinema is worth more than all four hours of the Liz Taylor version for my money."

Tim Dirks at AMC Filmsite : "Unarguably, the Paramount Studios film is campy, grandiose and unreal and ludicrous historically - filled with DeMille's usual mixture of sin and sex. Sexually-suggestive costumes adorn most of the female characters."

Hal Erickson at AllMovie : "To emphasize the "contemporary" nature of the film, DeMille adds little modernistic touches throughout: The architecture of Egypt and Rome has a distinctly art-deco look; a matron at a social gathering clucks "Poor Calpurnia...well, the wife is always the last to know"; and, after Caesar's funeral, Mark Anthony is chided by an associate for "all that 'Friends, Romans, Countrymen' business!" Cleopatra's barge scene and her suicide from the bite of a snake marked two of the most memorable sequences in DeMille's career. Remarkably, for all the enormous sets and elaborate costumes, Cleopatra came in at a budget of $750,000 -- almost $40 million less than the 1963 Elizabeth Taylor remake."

Mario Gauci at IMDb : "The film features a number of great scenes: Caesar's murder (partly filmed in a POV (point of view) shot), following which is a delicious jibe at Antony's famous oratory during Caesar's funeral as envisioned by Shakespeare; the long - and justly celebrated - barge sequence, in which Antony (intent on teaching Cleopatra, whom he blames for Caesar's death, a lesson) ends up being completely won over by her wiles; Cleopatra's own death scene is simply but most effectively filmed."

Wikipedia : "The film is also memorable for the sumptuous art deco look of its sets (by Hans Dreier) and costumes (by Travis Banton), the atmospheric music composed and conducted by Rudolph George Kopp, and for DeMille's legendary set piece of Cleopatra's seduction of Antony, which takes place on Cleopatra's barge."

Robert Reynolds at IMDb : "This movie is a typical DeMille PRODUCTION, with all the strengths-gorgeous sets, costumes and a sort of grandeur to all the proceedings-as well as the weaknesses-the lavishness often comes at the expense of things like the story, acting and plot. There's no question that it's beautiful (although, interestingly enough, none of it's five nominations for Academy Awards was for Interior Decoration.)"

Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony. Dutch postcard, promoting a visit to the American epic Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934). Photo: Paramount.

Dutch postcard, promoting a visit to the American epic Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934). Photo: Paramount. Credited on the card are Claudette Colbert (Cleopatra), Henry Wilcoxon (Marc Anthony) and Warren William (Julius Caesar). However, the guy on the right on this card is not Wilcoxon but Cleopatra's rival Pothinos (Leonard Mudie).

Dutch postcard. Photo: Paramount. Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra and Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony in Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Sources: Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Tim Dirks (AMC Filmsite), Wikipedia and IMDb.

Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony and Gertrude Michael as Caesar's wife Calpurnia. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 961. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. deMille, 1934).

Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra and Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 962. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Henri Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 963. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Warren William as Julius Caesar. French postcard by A.N., Paris, no. 965. Photo: Paramount. Publicity still for Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Deadly and fascinating

Wikipedia : "On July 1, 1934, the Motion Picture Production Code began to be rigidly enforced and expanded by Joseph Breen had just taken effect. Talkie films made before that date are generally referred to as Pre-Code films. However, DeMille was able to get away with using more risque imagery than he would be able to do in his later productions. He opens the film with an apparently naked, but strategically lit slave girl holding up an incense burner in each hand as the title appears on screen."

Ron Oliver at IMDb : "Claudette Colbert is perfectly cast in the title role - deadly & fascinating, it's almost like watching a desert viper act. Exhibiting mega star wattage in arguably her best role, Colbert is one of the legendary actresses who could hold her own without being swallowed by the lavish costumes & sets which fill her every scene."

John O'Grady at IMDb : "Colbert is admittedly somewhat miscast (her face is altogether Parisienne), but she handles the part with considerable charm. Warren William, usually a very limited actor, is as good a Caesar as I have seen on film, commanding and uncomfortable by turns; while Henry Wilcoxon is the definitive Mark Antony, laughing, brawling, swaggering, crude and brooding. C. Aubrey Smith as Enobarbus, the last of the hardcore Roman republicans, is perfect. Victor Milner's cinematography is superb, if old-fashioned. There is one magnificent pullback shot aboard Cleopatra's barge, with more and more stuff entering the frame, which as pure cinema is worth more than all four hours of the Liz Taylor version for my money."

Tim Dirks at AMC Filmsite : "Unarguably, the Paramount Studios film is campy, grandiose and unreal and ludicrous historically - filled with DeMille's usual mixture of sin and sex. Sexually-suggestive costumes adorn most of the female characters."

Hal Erickson at AllMovie : "To emphasize the "contemporary" nature of the film, DeMille adds little modernistic touches throughout: The architecture of Egypt and Rome has a distinctly art-deco look; a matron at a social gathering clucks "Poor Calpurnia...well, the wife is always the last to know"; and, after Caesar's funeral, Mark Anthony is chided by an associate for "all that 'Friends, Romans, Countrymen' business!" Cleopatra's barge scene and her suicide from the bite of a snake marked two of the most memorable sequences in DeMille's career. Remarkably, for all the enormous sets and elaborate costumes, Cleopatra came in at a budget of $750,000 -- almost $40 million less than the 1963 Elizabeth Taylor remake."

Mario Gauci at IMDb : "The film features a number of great scenes: Caesar's murder (partly filmed in a POV (point of view) shot), following which is a delicious jibe at Antony's famous oratory during Caesar's funeral as envisioned by Shakespeare; the long - and justly celebrated - barge sequence, in which Antony (intent on teaching Cleopatra, whom he blames for Caesar's death, a lesson) ends up being completely won over by her wiles; Cleopatra's own death scene is simply but most effectively filmed."

Wikipedia : "The film is also memorable for the sumptuous art deco look of its sets (by Hans Dreier) and costumes (by Travis Banton), the atmospheric music composed and conducted by Rudolph George Kopp, and for DeMille's legendary set piece of Cleopatra's seduction of Antony, which takes place on Cleopatra's barge."

Robert Reynolds at IMDb : "This movie is a typical DeMille PRODUCTION, with all the strengths-gorgeous sets, costumes and a sort of grandeur to all the proceedings-as well as the weaknesses-the lavishness often comes at the expense of things like the story, acting and plot. There's no question that it's beautiful (although, interestingly enough, none of it's five nominations for Academy Awards was for Interior Decoration.)"

Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony. Dutch postcard, promoting a visit to the American epic Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934). Photo: Paramount.

Dutch postcard, promoting a visit to the American epic Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934). Photo: Paramount. Credited on the card are Claudette Colbert (Cleopatra), Henry Wilcoxon (Marc Anthony) and Warren William (Julius Caesar). However, the guy on the right on this card is not Wilcoxon but Cleopatra's rival Pothinos (Leonard Mudie).

Dutch postcard. Photo: Paramount. Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra and Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Anthony in Cleopatra (Cecil B. DeMille, 1934).

Sources: Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Tim Dirks (AMC Filmsite), Wikipedia and IMDb.

Published on November 28, 2018 22:00

November 27, 2018

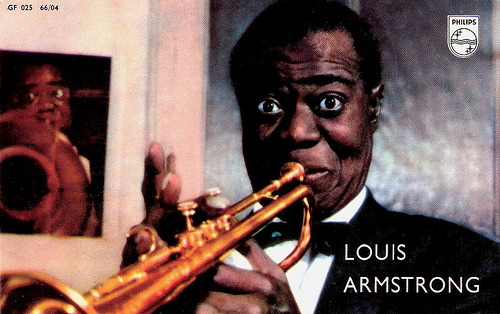

Louis Armstrong

Louis Armstrong (1901-1971) was The King of the Jazz Trumpet. Armstrong, nicknamed Satchmo, is renowned for his charismatic stage presence and voice almost as much as for his trumpet playing. He recorded hit songs for five decades and composed dozens of songs that have become jazz standards. Armstrong was one of the most important creative forces in the early development and perpetuation of Jazz. With his superb comic timing and unabashed joy of life, Louis Armstrong also appeared in more than thirty films.

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. CK-289. Photo: Arthur Grimm / Ufa.

German postcard by ISV, no. H 37.

Born in the Battlefield

Louis Daniel Armstrong was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in the Storyville District known as 'the Battlefield' in 1901. His parents were Mary Albert and William Armstrong. William abandoned the family shortly after, and Louis grew up poor in a single-parent household. He left school at the 5th grade to help support his family. He sang on street corners, sold newspapers and delivered coal.

Louis was 13 when he celebrated New Year's Eve on 31 December 1912 by running out on the street and firing a blank from a pistol that belonged to the current man in his mother's life. He was arrested and placed in the Colored Waif's Home for boys. There, he learned to play the bugle cornet and the clarinet and joined the home's brass band. Armstrong's first teacher Peter Davis taught him there to read music. After 18 months, Louis left the Home determined to become a musician.

The young Armstrong played in brass bands and riverboats in New Orleans, first on an excursion boat in September 1918. At 18, he got a job in the Kid Ory Band in New Orleans. Armstrong married Daisy Parker as his career as a musician developed. In 1922, he followed his mentor, Joe 'King' Oliver, to Chicago to play in the Creole Jazz Band. He made his first recordings with that band in 1923. While in Chicago, Armstrong networked with other jazz musicians, reconnecting with his friend, Bix Biederbecke, and made new contacts, which included Hoagy Carmichael and Lil Hardin.

Lil was a graduate of Fisk University and an excellent pianist who could read, write and arrange music. She encouraged and enhanced Louis' career, and they married in 1924. Armstrong became very popular and one of the genre's most sought after trumpeters. He travelled a great deal and spent considerable time in Chicago and New York. He first moved to the Big Apple in 1924 to join Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra. He stayed in New York for a while but moved back to Chicago in October of 1925.

Armstrong later went back to New York in 1929. Armstrong appeared on Broadway in Hot Chocolates, in which he introduced Fats Waller's Ain't Misbehavin', his first popular song hit. During that time, some of his most important and successful work was accomplished with his Hot Fives and Hot Sevens Bands. Armstrong's interpretation of Hoagy Carmichael's Stardust became one of the most successful versions of this song ever recorded, showcasing Armstrong's unique vocal sound and style and his innovative approach to singing songs that had already become standards. In 1931, Armstrong appeared in his first film, Ex-Flame. That year, Armstrong and Lil Hardin separated and later divorced in 1938.

Dale O'Connor at IMDb : "He made a tour of Europe in 1932. During a command performance for King George V, he forgot he had been told that performers were not to refer to members of the royal family while playing for them. Just before picking up his trumpet for a really hot number, he announced: 'This one's for you, Rex.'" After this Grand Tour of Europe, Satchmo became Armstrong's nickname. A London music magazine editor had written erroneously 'Satchmo' in an article (Armstrong's nickname was 'Satchelmouth') and the name stuck.

In 1937, Armstrong substituted for Rudy Vallee on the CBS radio network and became the first African American to host a sponsored, national broadcast. After his divorce, Louis married Alpha Smith in 1938. While maintaining a vigorous work schedule, as well as living and travelling back and forth to Chicago and California, Armstrong moved back to New York in the late 1930s and later married Lucille Wilson in 1942.

Dutch postcard by N.V. Int. Filmpers (I.F.P.), Amsterdam, no. 1035. Photo: Joel Elkins. Louis Armstrong in the 1955 version of the All Stars, with Trummy Young on trombone and vocals, and Edmond Hall on clarinet and vocals.

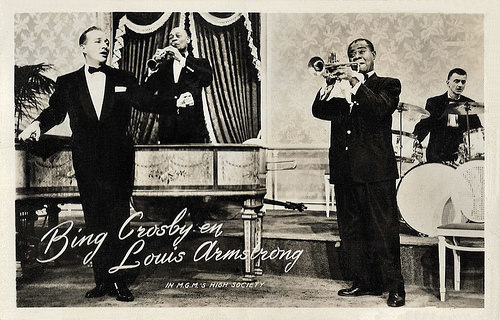

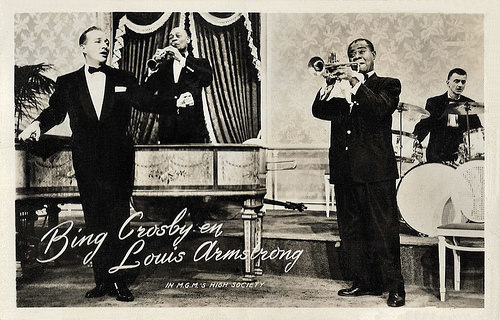

Dutch postcard by Uitg. Takken, Utrecht, no. 3024. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for High Society (Charles Walters, 1956) with Bing Crosby.

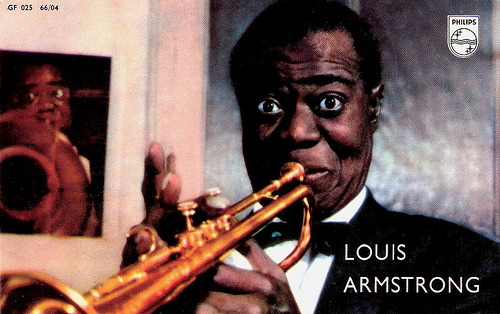

Dutch promotion card by Philips, no. GF 025 66/04.

One of the first truly popular African-American entertainers to 'cross over'

Louis Armstrong was also an influential singer, with his instantly recognisable gravelly voice. He demonstrated great mastery as an improviser, bending the lyrics and melody of a song for expressive purposes. He was also very skilled at scat singing.

Although his career as a recording artist dates back to the 1920s, when he made now-classic recordings with Joe 'King' Oliver, Bessie Smith and Jimmie Rodgers, as well as his own Hot Five and Hot Seven groups, his biggest hits as a recording artist came comparatively late in his life. Armstrong had nineteen Top Ten hits including When The Saints Go Marching In (1938), Mack the Knife (1955), Stompin' at the Savoy (1956) with Ella Fitzgerald, and What a Wonderful World (1967).

Armstrong's influence extends well beyond jazz, and by the end of his career in the 1960s, he was widely regarded as a profound influence on popular music in general. In 1964, Armstrong knocked The Beatles off the top of the Billboard Hot 100 chart with Hello, Dolly!, which gave the 63-year-old performer a U.S. record as the oldest artist to have a number one song.

Armstrong appeared in more than a dozen Hollywood films, usually playing a bandleader or musician. He appeared with Bing Crosby in the musical Pennies from Heaven (Norman Z. MacLeod, 1936), and with Mae West in Every Day's a Holiday (A. Edward Sutherland, 1937).

In the innovating musical Cabin in the Sky (Vincente Minnelli, Busby Berkeley, 1943) featuring an All Star, All Black cast, Louis played 'The Trumpeter' opposite Ethel Waters and Lena Horne. In 1947, he played himself opposite Billie Holiday in New Orleans (Arthur Lubin, 1947), which chronicled the demise of the Storyville district and the ensuing exodus of musicians from New Orleans to Chicago.

Armstrong also joined Danny Kaye and Virginia Mayo in the comedy A Song Is Born (Howard Hawks, 1948). The best parts of the film are the music scenes with Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Barnett, Lionel Hampton, and Benny Goodman, playing kick-arse Jazz. In The Glenn Miller Story (Anthony Mann, 1954), Armstrong jammed with Miller (James Stewart) and a few other noted musicians of the time.

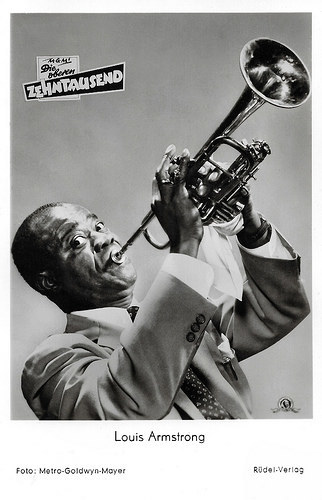

His most familiar role was as the bandleader in the musical High Society (Charles Walters, 1956). He functions as a very partisan Greek Chorus , who tells you right up front who he's pulling for to win Grace Kelly and he helps musically along the way, performing a duet with Bing Crosby.

In The Five Pennies (Melville Shavelson, 1959), the story of the cornetist Red Nichols, Armstrong played himself as well as singing and playing several classic numbers. With leading actor Danny Kaye, Armstrong performed a duet of When the Saints Go Marching In, during which Kaye impersonated Armstrong.

He also appeared in several European films, including the Italian-French musical Saluti e baci/The Road to Happiness (Maurice Labro, Giorgio Simonelli, 1953) with Georges Guétary , the German musical Die Nacht vor der Premiere/The Night before the Premiere (Georg Jacoby, 1959) with Marika Rökk , and the Danish musical Kærlighedens melodi/The melody of love (Bent Christensen, 1959) with Nina and Frederik .

Armstrong was one of the first truly popular African-American entertainers to 'cross over', whose skin colour was secondary to his music in an America that was extremely racially divided at the time. He rarely publicly politicised his race, often to the dismay of fellow African Americans, but Armstrong was the only Black Jazz musician to publicly speak out against school segregation in 1957 during the Little Rock crisis. His artistry and personality allowed him access to the upper echelons of American society, then highly restricted for black men. Despite his fame, he remained a humble man and lived a simple life in a working-class neighbourhood.

Louis Armstrong remained married to Lucille Wilson until his death in 1971, a month away from what would have been his 70th birthday on 4 August. Embittered by the treatment of blacks in his hometown of New Orleans, he chose to be buried in New York City at the Flushing Cemetery, not too far from his home in Corona, Queens. He left his entire estate to his beloved wife, who died in 1983. Armstrong wrote two autobiographies. His house in Corona, where Armstrong lived for almost 28 years, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977. Today, it is a museum where fans can check out his residence and its belongings as a citizen of New York City.

German postcard by Kolibri-Verlag, Minden/Westf., no. 765. no. CK-289. Photo: Alfa / Gloria / Kiebig. Publicity still for La Paloma (Paul Martin, 1959).

Vintage postcard, no. 111.

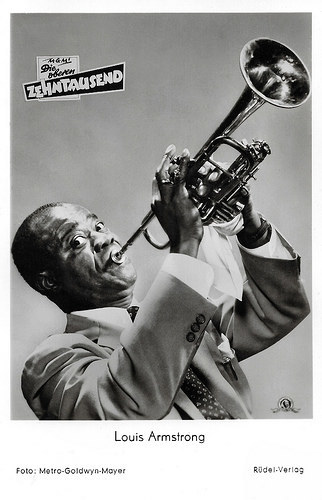

German postcard by Rüdel-Verlag, Hamburg-Bergedorf, no. 1988. Photo: MGM. Publicity still for High Society (Charles Walters, 1956). The German title of the film is Die oberen Zehntausend (The top ten thousand).

Sources: (IMDb), Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, Wikipedia and .

French postcard by Editions P.I., Paris, no. CK-289. Photo: Arthur Grimm / Ufa.

German postcard by ISV, no. H 37.

Born in the Battlefield

Louis Daniel Armstrong was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in the Storyville District known as 'the Battlefield' in 1901. His parents were Mary Albert and William Armstrong. William abandoned the family shortly after, and Louis grew up poor in a single-parent household. He left school at the 5th grade to help support his family. He sang on street corners, sold newspapers and delivered coal.

Louis was 13 when he celebrated New Year's Eve on 31 December 1912 by running out on the street and firing a blank from a pistol that belonged to the current man in his mother's life. He was arrested and placed in the Colored Waif's Home for boys. There, he learned to play the bugle cornet and the clarinet and joined the home's brass band. Armstrong's first teacher Peter Davis taught him there to read music. After 18 months, Louis left the Home determined to become a musician.

The young Armstrong played in brass bands and riverboats in New Orleans, first on an excursion boat in September 1918. At 18, he got a job in the Kid Ory Band in New Orleans. Armstrong married Daisy Parker as his career as a musician developed. In 1922, he followed his mentor, Joe 'King' Oliver, to Chicago to play in the Creole Jazz Band. He made his first recordings with that band in 1923. While in Chicago, Armstrong networked with other jazz musicians, reconnecting with his friend, Bix Biederbecke, and made new contacts, which included Hoagy Carmichael and Lil Hardin.

Lil was a graduate of Fisk University and an excellent pianist who could read, write and arrange music. She encouraged and enhanced Louis' career, and they married in 1924. Armstrong became very popular and one of the genre's most sought after trumpeters. He travelled a great deal and spent considerable time in Chicago and New York. He first moved to the Big Apple in 1924 to join Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra. He stayed in New York for a while but moved back to Chicago in October of 1925.

Armstrong later went back to New York in 1929. Armstrong appeared on Broadway in Hot Chocolates, in which he introduced Fats Waller's Ain't Misbehavin', his first popular song hit. During that time, some of his most important and successful work was accomplished with his Hot Fives and Hot Sevens Bands. Armstrong's interpretation of Hoagy Carmichael's Stardust became one of the most successful versions of this song ever recorded, showcasing Armstrong's unique vocal sound and style and his innovative approach to singing songs that had already become standards. In 1931, Armstrong appeared in his first film, Ex-Flame. That year, Armstrong and Lil Hardin separated and later divorced in 1938.

Dale O'Connor at IMDb : "He made a tour of Europe in 1932. During a command performance for King George V, he forgot he had been told that performers were not to refer to members of the royal family while playing for them. Just before picking up his trumpet for a really hot number, he announced: 'This one's for you, Rex.'" After this Grand Tour of Europe, Satchmo became Armstrong's nickname. A London music magazine editor had written erroneously 'Satchmo' in an article (Armstrong's nickname was 'Satchelmouth') and the name stuck.

In 1937, Armstrong substituted for Rudy Vallee on the CBS radio network and became the first African American to host a sponsored, national broadcast. After his divorce, Louis married Alpha Smith in 1938. While maintaining a vigorous work schedule, as well as living and travelling back and forth to Chicago and California, Armstrong moved back to New York in the late 1930s and later married Lucille Wilson in 1942.