Robin Helweg-Larsen's Blog, page 25

August 23, 2024

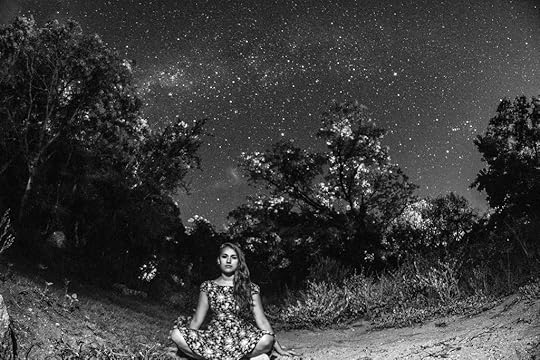

Early poem: Michael R. Burch, ‘Will There Be Starlight’

Will there be starlight

tonight

while she gathers

damask

and lilac

and sweet-scented heathers?

And will she find flowers,

or will she find thorns

guarding the petals

of roses unborn?

Will there be starlight

tonight

while she gathers

seashells

and mussels

and albatross feathers?

And will she find treasure

or will she find pain

at the end of this rainbow

of moonlight on rain?

*****

Michael R. Burch writes: “The real test of a poem, for me, is whether I can remember it or not. If I can’t remember a poem, if it doesn’t leave a lasting impression, it simply vanishes like a windblown tumbleweed and cannot be a “keeper.” I decided to apply an “instant recall” test to my own poems and translations, to see which ones leapt to mind first. Ironically, or perhaps not, several of these poems turned out to be about memories and/or how the human memory works, or sometimes doesn’t. ‘Will There Be Starlight’ is one.

“I wrote it around age 18 as a high school student and it has been published by TALESetc, Starlight Archives, The Word (UK), Poezii (in a Romanian translation by Petru Dimofte), The Chained Muse, Famous Poets & Poems, Grassroots Poetry, Inspirational Stories, Jenion, Regalia, Chalk Studio, Poetry Webring and Writ in Water. ‘Will There Be Starlight’ has also been set to music by the award-winning New Zealand composer David Hamilton and read on YouTube by Ben E. Smith. To have a poem written as a teenager translated into Romanian, set to music by a talented composer, performed by one of the better poetry readers, and published in multiple literary journals was not a bad start to my career as a poet!”

Michael R. Burch is an American poet who lives in Nashville, Tennessee with his wife Beth, their son Jeremy, two outrageously spoiled puppies, and a talkative parakeet. Burch’s poems, translations, essays, articles, reviews, short stories, epigrams, quotes, puns, jokes and letters have appeared in hundreds of literary journals, newspapers and magazines. He is also the founder and editor-in-chief of The HyperTexts, a former columnist for the Nashville City Paper, and, according to Google’s rankings, a relevant online publisher of poems about the Holocaust, Hiroshima, the Trail of Tears and the Palestinian Nakba. Burch’s poetry has been taught in high schools and universities, translated into 19 languages, incorporated into three plays and two operas, set to music 61 times by 32 composers, from swamp blues to classical, and recited or otherwise employed in more than a hundred YouTube videos. To read the best poems of Mike Burch in his own opinion, with his comments, please click here: Michael R. Burch Best Poems.

Photo: “Star Girl” by Tobias Mayr is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

August 21, 2024

Semi-formal: RHL, ‘Terminal’

Christian culture’s crucifixation

nails us to our seats as, station by station,

we travel the trammelled line

until we find

that terminal

more primal.

The humanstrain’s end-of-line stop

is Ragnarok.

Everyone please disembark

into the dark–

no light, no map.

Mind the Ginnungagap.

*****

This is as close as I get to religion: existential uncertainty. I’m a Militant Agnostic: “I don’t know… and neither do you!” Yet this attitude is apparently compatible with religion, being not that different from Eliot’s ‘East Coker‘:

O dark dark dark. They all go into the dark,

The vacant interstellar spaces, the vacant into the vacant,

The captains, merchant bankers, eminent men of letters

(…)

I said to my soul, be still, and let the dark come upon you

Which shall be the darkness of God.

But Christianity? I think not. Altogether too unlikely, with so many impossibilities packed into such a small understanding of the cosmos. We don’t know where we are headed, not just as individuals with finite lives, but as a species that is simultaneously developing space travel and genetic modifications… the possibilities are endless and the future, dark as well as light, is unknowable.

The poem is semi-formal with its loose iambics and paired rhymes or slant rhymes, but no structure beyond its natural flow. It was originally published in the Experimental section of a 2019 issue of Better Than Starbucks, and republished as part of work being spotlighted in The HyperTexts in August 2024.

Photo: “London Holborn tube station in Black and White effect” by Patrick Cannon Tax Barrister is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

August 19, 2024

R.I.P. Ann Drysdale… ‘Weirdness Observed’

What is she doing, the mad old bat,

Down on her knees in the garden?

In her busted boots and her happiness hat

She doesn’t know and she wouldn’t care

That the size of the arse sticking up in the air

Is shading so much of the garden.

She pulls out a weed, the mad old bat,

Out of the face of the garden.

She tuts at the trauma and fusses it flat

While the waste-not weed she will put to use

By turning it into salubrious juice

And giving it back to the garden.

What is she up to, the mad old bat

As she struts, stiff-kneed in the garden

With her doo-dah dog and her galloping cat?

Spreading compost and scattering seed

So one may sprout and the other may feed

In the windmill world of the garden.

She’s a cruel cartoon, is the mad old bat

As she talks to herself in the garden.

What on earth is this? and Good Lord, look at that!

And she squats and she mutters and giggles out loud

And informs her potatoes they’re doing her proud

As she creeps like a crone in the garden.

Where is she going, the mad old bat

As the sunset blesses the garden?

She is going nowhere, and that is that.

She will dig in the dark will the dawn sky pales

And the damp on her knees and the dirt in her nails

Go singing the song of the garden.

*****

Ann Drysdale, who died unexpectedly on August 16th (apparently in her sleep) was a superb poet and self-aware, self-directed, life-rich eccentric lover of the natural world, of gardens, of animals and birds, of unpretentious people in all walks of life. I knew her only through her poetry and our correspondence – which is to say, well enough to deeply regret that I never got to meet her in person.

The poem above was collected in Miss Jekyll’s Gardening Boots, Shoestring Press, 2015; as was the poem that I put up on this blog earlier this month, ‘When Mister Nifty Plays the Bones‘. Here is the bio that she chose to represent herself with:

“Ann Drysdale still lives in South Wales. She has been a hill farmer, water-gypsy, newspaper columnist and single parent – not necessarily in that order. She has written all her life; stories, essays, memoir, and a newspaper column that spanned twenty years of an eventful life. Her eighth volume of poetry – Feeling Unusual – came together during the strange times of Coronavirus and celebrates, among other things, the companionship of a wise cat and an imaginary horse.”

She was a much-loved member of the world of (especially formalist) poetry. George Simmers posted her ‘Song of Wandering Annie’ in the Snakeskin blog, and there is a tribute (and an enormous selection of her verse) in The HyperTexts. She was a truly good person.

August 17, 2024

Margaret Thatcher’s favourite poem: Charles Mackay, ‘No Enemies’

You have no enemies, you say?

Alas! my friend, the boast is poor;

He who has mingled in the fray

Of duty, that the brave endure,

Must have made foes! If you have none,

Small is the work that you have done.

You’ve hit no traitor on the hip,

You’ve dashed no cup from perjured lip,

You’ve never turned the wrong to right,

You’ve been a coward in the fight.

*****

I’m no fan of the excessive and unproductive trickle-down economics of Margaret Thatcher, other than to say that I’m also no fan of the excessive and unproductive Union bureaucracy that she came to fight. (That just means I’m a centrist, and centrists often have a hard time in Two-party First-past-the-post electoral systems. FPTP encourages dividing the country into Us and Them, and making everything a fight. I think Proportional Representation allows for more constructive government relationships.)

As reported in The Independent, in the docudrama ‘The Crown’, Margaret Thatcher fires half of her cabinet because of their “lack of grit as a consequence of their privilege and entitlement”. In response, Queen Elizabeth tells Thatcher that she’s playing a “dangerous game” making so many enemies, to which the prime minister replies that she is “comfortable” with having enemies, and she then recites Scottish poet Charles Mackay’s ‘No Enemies’. Mackay was a 19th century poet and journalist, now best remembered for his ‘Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds‘.

In real life, Thatcher was very fond of the poem, with a 2019 BBC documentary revealing that she kept it on her desk.

“Food fight.” by Free the Image is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

August 16, 2024

Kelly Scott Franklin, ‘Fez’

Haberdashers, it is true,

are hardly known for derring-do,

or swashbuckling, or hurling stones,

or smashing heads and dragon bones.

But let that man exalted be,

that Hercules of hattery,

whose name no history ever says:

all hail the man who made the fez.

*****

Kelly Scott Franklin writes: “This comes from my collection-in-progress, A Curious Alphabet of Hats, a whimsical alphabet book of poems about, well, hats. The Fez is not a silly hat from its origins. But it is comical to see American members of the Shriners club wearing it while they drive their go-carts in parades. I’m especially proud of the alliterative-allusive-hyperbole “that Hercules of hattery.” This poem and more entries from A Curious Alphabet of Hats have appeared here (Light Poetry Magazine) and another here (Lighten Up Online). I have also begun A Curious Alphabet of Birds, but haven’t gotten any farther than Dodo.”

Kelly Scott Franklin lives in Michigan with his wife and daughters. He teaches American Literature and the Great Books at Hillsdale College. His poems and translations have appeared in AbleMuse Review, Literary Matters, Driftwood Literary Magazine, Iowa City Poetry in Public, National Review, Thimble Literary Magazine, Ekstasis, and elsewhere. His essays and reviews can be found in Commonweal, The Wall Street Journal, The New Criterion, Local Culture, and elsewhere.

https://www.hillsdale.edu/faculty/kelly-scott-franklin/

Photo: “Kirk Talks to Spock about his ‘Fez Addiction'” by The Rocketeer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

August 14, 2024

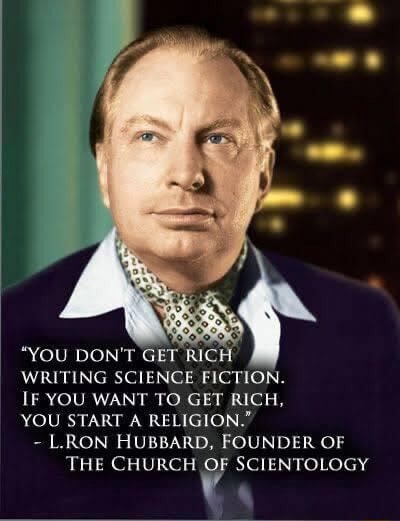

Semi-formal: RHL, ‘Laffable Religion’

No matter how seemingly affable,

a priest always hopes to be greased;

while others, invoking hellfire,

have us wait for our trip in the hearse

and preach in their suits neatly creased,

these fishers of men that are gaffable,

in this world that they’ve made mud and mire.

That the point of a flock’s to be fleeced

can only be said in light verse;

for religion is simply so laughable

it’s amazing it’s not yet deceased.

*****

Isn’t it amazing that the Pope can claim to have voluntarily taken a vow of lifelong poverty, and millions of his supporters who live in involuntary poverty send money to support him living in a palace? Is it different from a billionaire politician soliciting donations from his impoverished supporters? Is the human need to glorify the tribal god and the tribal leader never going to end?

This poem was first published in The HyperTexts, as part of the August 2024 Spotlight.

August 12, 2024

Shamik Banerjee, ‘Masjid Road’

Fishmongers’ cleaver knives don’t rest at all;

Their heavy thuds outdo the termless spiels

Of colporteurs dispensing large and small

Versions of holy books. On mud-sunk wheels,

Waxed apples, sapodillas, apricots

Effuse their fragrance, trapping passersby

Who check the rates, then stand submerged in thoughts—

Some fill their punnets, some leave with a sigh.

Outside the mosque, blind footpath dwellers wait

To hear the clinking sound—the sound of true

Relief—while dogs, flopped by the butcher’s gate,

Get jumpy when he throws a hunk or two.

Loudspeakers, placed on high, say “call to prayer”

And all work halts; there’s silence in the air.

*****

Shamik Banerjee writes: “Crammed with saree shops, bakeries, small abattoirs, vegetable vendors, holy book distributors, toy stores, and sundry other things, Masjid Road is one of the very few tireless market places in Guwahati, my hometown. As a frequent visitor to this place of never-ending commotion and bustle, I have always been fascinated by these sellers’ devotion to their work. Though rest is a distant guest here, all activities come to a standstill right when the nearby mosque sends out the call-to-prayer through towering loud speakers.”

Shamik Banerjee is a poet from Assam, India, where he resides with his parents. His poems have been published by Sparks of Calliope, The Hypertexts, Snakeskin, Ink Sweat & Tears, Autumn Sky Daily, Ekstasis, among others. (‘Masjid Road’ was first published by Bellwether Review.) He secured second position in the Southern Shakespeare Company Sonnet Contest, 2024.

Photo: “Indian Shops” by Scalino is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

August 10, 2024

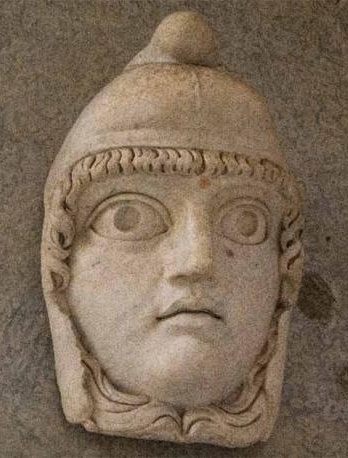

Weekend read: long poem: ‘Catullus LXIII’ translated by George Simmers

Across the sea goes Attis in his ship of sleek rapidity,

To Phrygia, and its forest, which he rushes into eagerly,

The great goddess’s territory, her tree-dark sanctuary.

There he grabs a flint; he jabs and savages his genitals,

Stabs until he’s sure he’s lost the burden of virility;

His blood spills its darkness on the sacred ground surrounding him.

SHE now, never he, SHE reaches for a tambourine,

The tympanum, Cybele, that is used by your initiates,

She beats out her message on the leather of the instrument;

Up she rises, and calls out to all her followers:

My she-priests hurry, to these woods of our divinity.

Hurry all you wanderers, all great Cybele’s worshippers,

You searchers for an otherwise, you riskers and adventurers

You voyagers who’ve dared the seas that match you in your truculence,

You like me whose dream has been self-immolated genitals,

Like me detesting Venus with the utmost of ferocity,

Set free your minds with the liberty of ecstasy.

Gladden our goddess, hurry here to worship her,

Hurry to this Phrygian domain of femininity,

Hurry to the cymbals, to the gentle flute’s seductiveness,

Towards the fevered drums and the Maenads’ ululations

There we must hurry for the celebration ritual.

Attis thus addressed them; she had all the look of womanhood;

Tongues lisped lovingly and cymbals clashed resoundingly.

Attis led on frenziedly, her wild breath labouring

Free as a heifer who’s escaped the yoke of drudgery,

Weary in her lungs, she through the woods leads rhythmically

The Gallae, who are following behind her storming leadership.

They reach the home of Cybele, wearied out and staggering,

Hungry, over-stretched, exhausted by excessiveness.

Sleep commands their eyelids to slide down sluggishly

Excitement leaves their bodies; rage gives way to drowsiness.

Dawn comes. Sunlight. The golden face that radiates

Alike above the firm soil and the great sea’s turbulence,

Which drives away darkness and banishes the weariness

Even from Attis, who is gradually awakening.

(For the goddess Pasithea’s taking Somnus to her bosom now.)

Attis, pseudo-woman, is freed now from delirium

Remembers what she did before, and sees herself now lucidly,

And knows what she has lost, and now her heart weighs heavily.

It labours in her body as she turns and walks back steadfastly,

Steadfastly and sadly, heading back towards her landing-place.

Her tearful eyes look out to sea; she renders this soliloquy

Remembering her birthplace despairingly, lamentingly.

My motherland, my origin, the one place that created me,

I must shun you like a thief now, like some dishonest runaway.

Deserting you for Ida, for a bleak and chilly wilderness,

Where brute beasts lurk, fired by hunger and rapacity.

Freed now from my madness by the shock of the reality,

My eyes weep with a longing for the home that was my nourisher.

Must life be now this wilderness, with only fading memories

Of when I was a man – but I have severed that identity –

A young man, supple, and the flower of the gymnasium,

A champion of champions among the oily combatants

Who wrestled for the glory – one who won the admiration

And the friendship of so many – how my home was garlanded!

But nevermore now I’ve become Cybele’s mere serving-wench,

Now that I’m a Maenad, a half-man, whose sterility

Must sentence me to exile, to a life of pointless wandering,

Neighbour to the boar and the wild deer in its solitude.

On these wild slopes of Ida, shadowed by the peaks of Phrygia.

How I hate my rashness; my regret becomes an agony,

Her words flying upward reached the ears of a deity,

They reached the ears of Cybele, who unleashed from their harnesses

The lions of her anger, with instructions to the left-hand one:

‘Go seek out Attis, be my agent of ferocity,

Pursue him till he’s overtaken by insanity,

Make him regret attempting to escape from my supremacy,

Lash your flanks with your tail, whip up your aggressiveness

Let the place re-echo with untamed outlandish bellowing,

Toss your long red mane in anger,’ so ordered Cybele,

Loosening the brute, who charged away unstoppably,

Raging, careering, crashing through the undergrowth,

Till it reached the white shore, where the sea was opalescent,

And that is where it saw him, Attis, solitary, delicate.

The lion charged and Attis, in a terrified delirium,

Fled towards the forest, to a destiny of hopelessness,

To existence as a slave there, the property of Cybele.

Great Goddess Cybele, Lady of Dindymus,

Vent your anger, I beseech you, far from my place of residence.

May only others feel your goad to madness and to ecstasy.

*****

George Simmers writes: “I’m not normally one for explaining poems, but my Englished version of Catullus’s poem LXIII in the current Snakeskin might be fairly mystifying to anyone coming to it unprepared.

“This is a poem that is over two thousand years old, and a remarkable one. The Victorian critic W.Y. Sellar described the ‘Attis’ as the most original of all Catullus’s poems: ‘As a work of pure imagination, it is the most remarkable poetical creation in the Latin language.’

“First – to deal with a possible misconception; the Attis of this poem is not the god of that name, but a young Greek man who sails to Phrygia, the home of the Great Mother, the goddess Cybele (pronounce the C hard, like a K). In homage to her he castrates himself, to become like one of her Galli, or attendant priests. Attis celebrates jubilantly, but next morning wakes up and registers the finality of what he has done, and the irrecoverable loss of his previous identity. The poem ends with Cybele setting her lions onto him, to drive him into the forest of madness.

“Summarising the story bluntly makes it sound like a simple fable of self-harm and regret, but Catullus is not a simple poet. The poem is made more complex by the intensity of his identification both with the exultant castrated Attis, and with his later regret. Another way of looking at the poem is as a tragedy – Attis’s desire to reshape himself is a hubris that leads to his destruction. Yet although Attis is labelled a pseudo-woman (‘notha mulier’) the reality of his desire to become a woman, and the intensity of his joy when he has liberated himself from maleness, are never in doubt. Significantly, when he later expresses regret, it is not for the loss of his sexual identity, but for his social one. It is possible to see the poem as an expression of the conflict within the poet himself, between his wayward hedonistic urges and his strict Roman ethic; he imagines an extreme case of abandoning a Roman (upright male) identity and discovering the consequences.

“The poem’s intensity is in part created by the metre – galliambic. There may be Greek precedents – scholars disagree, I think – but this poem has no known fore-runner in Latin verse. It seems to be based on the rhythms of the Galli’s ceremonial music (at the Roman Megalesian festivals, presumably, where the Great Mother was celebrated, by priests carrying tambourines and castrating-knives). It is an insistent, forward-driving metre, with a unique line ending, a pattering of three short syllables. English versification is different from Roman, and direct imitation of the galliambic metre in English does not work (although Tennyson had a go in his poem Boadicea). I have tried to find an equivalent that produces a similar forward-driving rhythm. It is based on a line of two halves; before the caesura I have allowed myself some freedom, to avoid predictability, but the second half of every line hammers with dactyls, always ending with a three-syllable word or phrase. This is the best solution I’ve found to the poem’s challenge. I’ve looked at various free-verse translations, but they all seem rather slack, lacking the energy of the original. Translations into blank verse or heroic couplets make the poem too staid. The prosody of the original was unique, controlled, purposeful, and a translation needs to be equally unexpected and distinctive.

“I suspect that my version may work better spoken aloud than on the page – but then I’m attracted to T.J. Wiseman’s theory that the original poem was originally written for performance (perhaps as accompaniment to a dance, perhaps at a Megalesian festival). Elena Theodorakopoulos agrees, and in a rather good essay available on the Internet, has written:

“I am convinced that the poem must have been written with performance at or around the Megalesia in mind. My suggestion is that it was written for one of the gatherings patrician families held at their homes during the Megalesia [….] It makes sense to imagine the poem performed at such an event: the thrill of the violence and the orgiastic frenzy, the mystery of who exactly Attis was, and the sexual ambivalence of the performance, would all have provided the perfect ambience for such a gathering. And when the final lines are spoken, asking the great goddess to visit others with her fury and to keep away from the speaker’s house (domus), they are spoken by the poet himself, whose identification with Attis’ frenzy during the reading must help to appease the goddess and to keep the noble domus in which the performance has taken place safe from harm.

“Catullus LXIII is a poem full of subtleties and mysteries (I keep on finding new things in it, and new ways to tweak my version,and you can expect the translation in Snakeskin to be updated from time to time). Like most readers I was first attracted to Catullus by his short poems of love and hate. I am gradually discovering that there was so much more to him. I’m now looking at poem 64…”

*****

George Simmers used to be a teacher; now he spends much of his time researching literature written during and after the First World War. He has edited Snakeskin since 1995. It is probably the oldest-established poetry zine on the Internet. His work appears in several Potcake Chapbooks, and his recent diverse collection is ‘Old and Bookish’. ‘Catullus LXIII’ is from Snakeskin 320, and the explanation is from the Snakeskin blog.

Photo: from Snakeskin 320 (August/September 2024)

August 9, 2024

Using form: Experimenting: Ann Drysdale, ‘When Mister Nifty Plays the Bones’

With things like tongs in the palm of his hand

Tongue-depressors or langues-de-chat

He tappets the rhythm of his one-man-band

As he struts in the gutter with a tra-la-la.

He twinkles his fingers and he flicks his wrist

Hey-diddle-diddle and fiddle-de-dee

And his two tame twiddlesticks jump and twist

With a click-click-clackety, one-two-three

For Nifty’s bones are made of wood

And they click like sticks with a restless chatter

His brass as he passes is loud and good

But his rattling bones are a different matter

His drum tum-tums and his trombone groans

And his hi-hat cymbal softly sighs

But all I can hear is the homely bones

That sing out the song in his small sad eyes

He dances a foxtrot, quick-quick-slow

And the hi-hat hisses with a whispered yes

But the bones, bones, bones with their no-no-no

Tick-tock to the tune of uselessness

When Mister Nifty dances by

His fingers flicker and his brass bells shine

But a part of my heart feels cold and dry

As his lonely bones call out to mine.

*****

Ann Drysdale writes “I made this poem because I wanted to see if I could turn words into music, with assonance and dissonance, chiming and clashing like the components of Mr. Nifty’s one man marching band. Laying aside conventional metre and putting boom, boom, boom alongside tum titty tum titty tum. I wanted it to sing and to dance to itself, and for the reader to dance along with it.”

The poem was collected in Miss Jekyll’s Gardening Boots, Shoestring Press, 2015.

Ann Drysdale still lives in South Wales. She has been a hill farmer, water-gypsy, newspaper columnist and single parent – not necessarily in that order. She has written all her life; stories, essays, memoir, and a newspaper column that spanned twenty years of an eventful life. Her eighth volume of poetry – Feeling Unusual – came together during the strange times of Coronavirus and celebrates, among other things, the companionship of a wise cat and an imaginary horse.

Illustration – supplied by Ann Drysdale

August 7, 2024

Using form: Ruba’i: RHL, ‘Ancient Tales of Love and War’

The pipes and women wail and skirl,

deaths following the flowering girl.

Ancient tales of love and war

show costs of dimple or a curl.

Tamil spear tips illustrate

intent before the towering gate;

bangles slide on her young wrists;

kings make war when made to wait.

Gods and goddesses choose sides:

a Trojan steals a youthful bride.

Who Trojans were we’ll never know –

Greeks burn the city, once inside.

A lovely face, a swelling bust –

and treasure, fame – inspired by lust

kings storm the ramparts, steal the girl,

before, like all, they turn to dust.

*****

This poem was inspired by a blog post in ‘Horace & friends’ on ‘Doing without consolation – Tamil poetry, Yeats and Simone Weil‘. The author, Victoria, touches on a lot more topics than my small piece does; visit her blog to see how Yeats’ “Like a long-legged fly upon the stream / Her mind moves upon silence” connects to ancient Tamil as well as ancient Greek poetry…

My poem here is in iambic tetrameter (with some liberties taken), rhyming AABA in English ruba’i form. It was published in the current (August 2024) Snakeskin, issue 320.

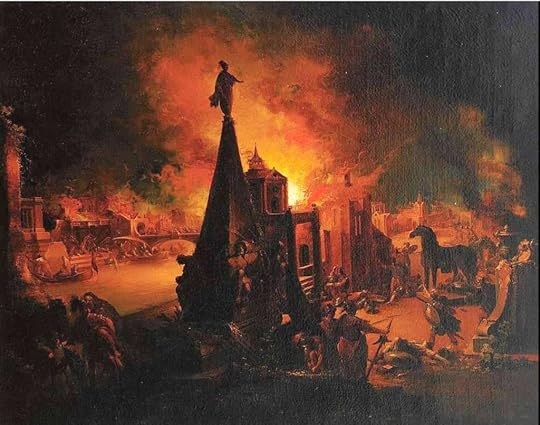

Illustration: The Fall of Troy by Johann Georg Trautmann (1713–1769)