Sarah Fine's Blog, page 12

February 1, 2012

Stuck to your partner like glue ... or running for the hills.

Basic attachment theory posits that humans are driven to form close connections with other people, but how we do that and how we feel about it is influenced by our early relationship experiences. Through interactions with our caregivers, we develop expectations of other people. So, for example, a baby with an attentive, responsive caregiver will develop the expectation that the caregiver is a source of safety and a provider of comfort. As a result, that baby will readily seek out that specific caregiver when anxious, and will be pretty darn upset if he's separated from that caregiver. However, if the baby has learned that the caregiver is cold and unresponsive, he will have an entirely different set of expectations and behaviors.

Adult attachment theory applies that idea of "attachment" to adult romantic relationships. On Monday, some of you were commenting about relationships in general, but this concept is generally reserved for romantic bonds. There's been a lot of attempts to map child attachment styles to those identified in adults, but findings from studies suggest that the connection, while definitely there, is moderate at best. Your childhood attachment style will not necessarily be your attachment style as an adult in a romantic relationship. However, there's a bit of evidence that suggests we choose partners who confirm our existing beliefs about relationships and intimacy.

Adult attachment theory applies that idea of "attachment" to adult romantic relationships. On Monday, some of you were commenting about relationships in general, but this concept is generally reserved for romantic bonds. There's been a lot of attempts to map child attachment styles to those identified in adults, but findings from studies suggest that the connection, while definitely there, is moderate at best. Your childhood attachment style will not necessarily be your attachment style as an adult in a romantic relationship. However, there's a bit of evidence that suggests we choose partners who confirm our existing beliefs about relationships and intimacy.

The basic attachment styles for adults:

Secure. This was #2 in Monday's post. Adults with a secure attachment style (or low anxiety, low avoidance on that quiz) find it easy to trust and be in relationships, and they tend to view relationships positively. They often have a history of warm, trusting connections, and are comfortable with intimacy--but not afraid of independence. About 60% of people describe themselves this way.

Preoccupied (also called "resistant"). This was #3 in Monday's post. Adults with preoccupied attachment style (low avoidance, high anxiety on the quiz) might seem kinda clingy. They seek approval and intimacy, but may end up being overly dependent. They rate themselves less positively than those who have secure attachment styles. About 20% of people describe themselves this way.

Avoidant. This was #1 in Monday's post, and about 20% of people describe themselves this way. But there are two types.

Fearful (high anxiety, high avoidance). These folks want to have close relationships but feel uncomfortable with being close to others. They might not trust partners, but they don't feel that great about themselves, either. Dismissive (this would be low anxiety, high avoidance). These folks are highly independent and don't value (relatively speaking) intimacy. They may view others less positively than they view themselves, and they may distance themselves from a partner if there's conflict or rejection. Both Dismissive and Fearful folks tend to hide or suppress their feelings ... but Dimissive peeps are more successful at it.There's solid research that shows that secure parents tend to have securely attached kiddos, and parents with one of the insecure attachment styles have kids who are more likely to show one of the insecure styles (resistant, avoidant, or disorganized).

So ... you know, I could go on and on. The field of attachment is HUGE, and the research spans the last five decades. I think I'll stop here for today, but if you're a writer thinking about romantic relationships (or parent-child relationships), you might want to investigate the concept of attachment in more depth, as it's a great way to build a character whose thoughts and actions form a cohesive pattern, especially if that character has some complex past relationships, either with parents or previous romantic partners.

And it's Wednesday! The first of the month! Which means Laura is tackling this month's Sisterhood of the Traveling Blog question: "What kind of book do you read for inspiration?" Head on over to her blog to see her answer!

Also--let me know if you have questions about attachment (for book-research/character development purposes) and I'll try to answer them in future posts!

Adult attachment theory applies that idea of "attachment" to adult romantic relationships. On Monday, some of you were commenting about relationships in general, but this concept is generally reserved for romantic bonds. There's been a lot of attempts to map child attachment styles to those identified in adults, but findings from studies suggest that the connection, while definitely there, is moderate at best. Your childhood attachment style will not necessarily be your attachment style as an adult in a romantic relationship. However, there's a bit of evidence that suggests we choose partners who confirm our existing beliefs about relationships and intimacy.

Adult attachment theory applies that idea of "attachment" to adult romantic relationships. On Monday, some of you were commenting about relationships in general, but this concept is generally reserved for romantic bonds. There's been a lot of attempts to map child attachment styles to those identified in adults, but findings from studies suggest that the connection, while definitely there, is moderate at best. Your childhood attachment style will not necessarily be your attachment style as an adult in a romantic relationship. However, there's a bit of evidence that suggests we choose partners who confirm our existing beliefs about relationships and intimacy.The basic attachment styles for adults:

Secure. This was #2 in Monday's post. Adults with a secure attachment style (or low anxiety, low avoidance on that quiz) find it easy to trust and be in relationships, and they tend to view relationships positively. They often have a history of warm, trusting connections, and are comfortable with intimacy--but not afraid of independence. About 60% of people describe themselves this way.

Preoccupied (also called "resistant"). This was #3 in Monday's post. Adults with preoccupied attachment style (low avoidance, high anxiety on the quiz) might seem kinda clingy. They seek approval and intimacy, but may end up being overly dependent. They rate themselves less positively than those who have secure attachment styles. About 20% of people describe themselves this way.

Avoidant. This was #1 in Monday's post, and about 20% of people describe themselves this way. But there are two types.

Fearful (high anxiety, high avoidance). These folks want to have close relationships but feel uncomfortable with being close to others. They might not trust partners, but they don't feel that great about themselves, either. Dismissive (this would be low anxiety, high avoidance). These folks are highly independent and don't value (relatively speaking) intimacy. They may view others less positively than they view themselves, and they may distance themselves from a partner if there's conflict or rejection. Both Dismissive and Fearful folks tend to hide or suppress their feelings ... but Dimissive peeps are more successful at it.There's solid research that shows that secure parents tend to have securely attached kiddos, and parents with one of the insecure attachment styles have kids who are more likely to show one of the insecure styles (resistant, avoidant, or disorganized).

So ... you know, I could go on and on. The field of attachment is HUGE, and the research spans the last five decades. I think I'll stop here for today, but if you're a writer thinking about romantic relationships (or parent-child relationships), you might want to investigate the concept of attachment in more depth, as it's a great way to build a character whose thoughts and actions form a cohesive pattern, especially if that character has some complex past relationships, either with parents or previous romantic partners.

And it's Wednesday! The first of the month! Which means Laura is tackling this month's Sisterhood of the Traveling Blog question: "What kind of book do you read for inspiration?" Head on over to her blog to see her answer!

Also--let me know if you have questions about attachment (for book-research/character development purposes) and I'll try to answer them in future posts!

Published on February 01, 2012 03:28

January 30, 2012

Getting Attached

On Wednesday, I'm going to talk a little about a huge concept in the psychological literature: attachment. It's a construct that encompasses the bond between caregiver and child. But there's another, related body of research, one that explores the nature of adult romantic relationships. That's the one I'm going to focus on this week.

But first! Let's get you guys thinking about this stuff. Two ways to do this: the quick and dirty, or the more in-depth.

If you want more in-depth, go here and take the quiz (I did it, and it took me about 5 minutes to do it and read the results).

If you're short on time, just read the paragraphs below and think about which one fits you (or, since most of you are writers, you can think about a character of yours):

I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don't worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn't really love me or won't want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.*And that's it! More on Wednesday. But if you're craving more brain food for today, go check out Lydia's Medical Monday post, and Laura's Mental Health Monday post!*These questions come from Hazan & Shaver, 1987

But first! Let's get you guys thinking about this stuff. Two ways to do this: the quick and dirty, or the more in-depth.

If you want more in-depth, go here and take the quiz (I did it, and it took me about 5 minutes to do it and read the results).

If you're short on time, just read the paragraphs below and think about which one fits you (or, since most of you are writers, you can think about a character of yours):

I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don't worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn't really love me or won't want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.*And that's it! More on Wednesday. But if you're craving more brain food for today, go check out Lydia's Medical Monday post, and Laura's Mental Health Monday post!*These questions come from Hazan & Shaver, 1987

Published on January 30, 2012 03:33

January 23, 2012

The Awesomeness of Attributions

Human beings are such amazing, complex creatures. We process huge amounts of information quickly--and half the time, we are not even fully aware of exactly how we get from point A to point B, cognitively speaking. Awhile back, I did a post about information processing, in response to a question about how two different people might end up reacting completely differently to the same situation. It was more of a broad overview, so today I'm going to talk a little about something more specific: ATTRIBUTIONS OF INTENT.

Oh yeah. Sounds like a sexy topic, doesn't it?

It should be, for any writer. Or any student of human behavior in general. Here's a very basic model:

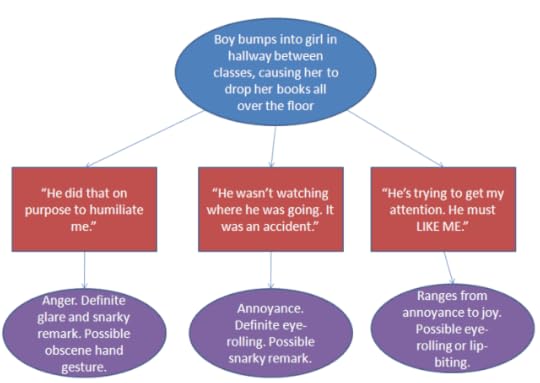

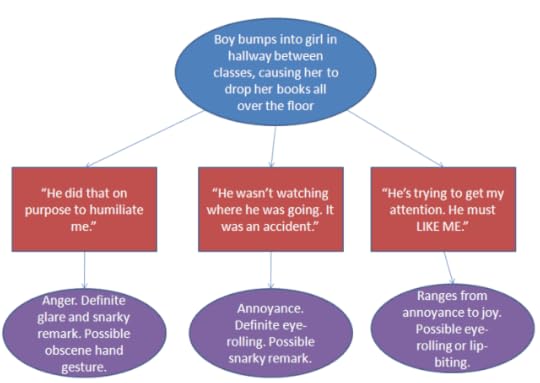

Here, something happens to a person. And that person then has to decide WHY it happened. That decision is completely critical to how the person ends up feeling--and responding--to the event.

Here, something happens to a person. And that person then has to decide WHY it happened. That decision is completely critical to how the person ends up feeling--and responding--to the event.

Now, sometimes, another person does something TO us. When that happens, we have to make an ATTRIBUTION OF INTENT. In other words, we have to make a guess about the other person's intention when he/she did something to us.

Sometimes, the person's intent is obvious, either because he tells us why he's doing something, or because the emotional and situational cues are really clear. But this is the delicious part: so often, the information about the other person's intentions is incomplete. The cues are ambigious. And so we have to guess.

Here's an example of a potentially ambigious situation, and how attributions of intent come into play:

Assume that, in this situation, it's really not clear from the guy's facial expression or body language whether he did it on purpose or not, at least, if you were watching from the outside. She has to rely on her own conclusions about what's happened. Depending on the girl's attribution of the guy's intent, she might feel and respond very differently. And with this single situation, I can think of at least a few more attributions that would lead to even more varied responses (like, the girl decides it was actually all her fault for running into the boy, and feels ashamed of herself and sad).

Individuals end up with what we call an "attributional style," meaning that each person tends to make similar kinds of attributions across situations. There's one style in particular, hostile attributional style, in which the person assumes the other individual's intentions are hostile, even in the face of ambiguous or neutral information. You've probably met people like this, right? Hostile attributional style is associated with higher levels of aggression in children and paranoia in adults. Another attributional style, one in which a person attributes the causes of bad events to herself, is associated with depression. Attributions matter.

There are several factors that predict what type of attributions a person makes. Individual temperament and level of emotional reactivity in conflict situations, high levels of hostile interactions in parent-child relationships, attachment security with parents, and experiences of acceptance or rejection from peers have all been shown to predict attributional style. In the moment, past experiences with the specific person, availability of contextual information (an event that took place right before, the other person's facial expression and emotional cues, etc.), and the individual's mood would also influence the type of attribution that results.

Now, personally, it's good to be aware of the attributions you're making--and it's sometimes good to challenge them a little instead of accepting them as objective truth. And for writing, well. Making your character's attributions clear to the reader can help you keep a character sympathetic, even when the person is responding in a way the reader might not.

So, that's attributions in a nutshell. How do you handle this in your writing? Have you ever thought about it like this before? And what about in real life? Have your attributions of someone's intent ever been wrong?

And of course, because it's Monday, go visit Lydia for her Medical Monday post, and Laura for her Mental Health Monday post!

Oh yeah. Sounds like a sexy topic, doesn't it?

It should be, for any writer. Or any student of human behavior in general. Here's a very basic model:

Here, something happens to a person. And that person then has to decide WHY it happened. That decision is completely critical to how the person ends up feeling--and responding--to the event.

Here, something happens to a person. And that person then has to decide WHY it happened. That decision is completely critical to how the person ends up feeling--and responding--to the event. Now, sometimes, another person does something TO us. When that happens, we have to make an ATTRIBUTION OF INTENT. In other words, we have to make a guess about the other person's intention when he/she did something to us.

Sometimes, the person's intent is obvious, either because he tells us why he's doing something, or because the emotional and situational cues are really clear. But this is the delicious part: so often, the information about the other person's intentions is incomplete. The cues are ambigious. And so we have to guess.

Here's an example of a potentially ambigious situation, and how attributions of intent come into play:

Assume that, in this situation, it's really not clear from the guy's facial expression or body language whether he did it on purpose or not, at least, if you were watching from the outside. She has to rely on her own conclusions about what's happened. Depending on the girl's attribution of the guy's intent, she might feel and respond very differently. And with this single situation, I can think of at least a few more attributions that would lead to even more varied responses (like, the girl decides it was actually all her fault for running into the boy, and feels ashamed of herself and sad).

Individuals end up with what we call an "attributional style," meaning that each person tends to make similar kinds of attributions across situations. There's one style in particular, hostile attributional style, in which the person assumes the other individual's intentions are hostile, even in the face of ambiguous or neutral information. You've probably met people like this, right? Hostile attributional style is associated with higher levels of aggression in children and paranoia in adults. Another attributional style, one in which a person attributes the causes of bad events to herself, is associated with depression. Attributions matter.

There are several factors that predict what type of attributions a person makes. Individual temperament and level of emotional reactivity in conflict situations, high levels of hostile interactions in parent-child relationships, attachment security with parents, and experiences of acceptance or rejection from peers have all been shown to predict attributional style. In the moment, past experiences with the specific person, availability of contextual information (an event that took place right before, the other person's facial expression and emotional cues, etc.), and the individual's mood would also influence the type of attribution that results.

Now, personally, it's good to be aware of the attributions you're making--and it's sometimes good to challenge them a little instead of accepting them as objective truth. And for writing, well. Making your character's attributions clear to the reader can help you keep a character sympathetic, even when the person is responding in a way the reader might not.

So, that's attributions in a nutshell. How do you handle this in your writing? Have you ever thought about it like this before? And what about in real life? Have your attributions of someone's intent ever been wrong?

And of course, because it's Monday, go visit Lydia for her Medical Monday post, and Laura for her Mental Health Monday post!

Published on January 23, 2012 03:41

January 18, 2012

The Power of Expectations

This month's Sisterhood of the Traveling Blog question came from yours truly:

This month's Sisterhood of the Traveling Blog question came from yours truly:Where do your expectations for your writing (career/skill/quality/achievements) come from? Is the source internal, external, or both? And how do you cope when you don't meet them?Lydia's answer is here, and Laura's is here. Deb will be up next week. As for me...

My expectations for my writing come from the same place the rest of my expectations of myself come from. And instead of telling you flat out, I will share a little story from my childhood.

My parents decided I was ready to go to kindergarten when I was four. Sure, my birthday wasn't until the very end of October and I couldn't legally start public school where we lived, but they decided I was ready enough to put me in some sort of church kindergarten, and then a different private school for first grade. And I have a memory, a very hazy one, but I've checked with my parents and they confirm the logistical details are accurate:

I am sitting in an empty classroom, at a table with a bunch of chairs around it. Child-sized. And I am holding a pencil, and looking down at some kind of test. I think it was an entrance exam for that private school, though at the time I only understood it as some sort of worksheet I was supposed to complete, and that the school people wanted to see if I could do it. I remember thinking only one thing:

I will SHOW these people what I can do.

I was five.

My expectations of what I can and should achieve come from inside of me. And I expect a lot. I know I said I don't study writing craft, but that doesn't mean I don't work on my writing, that I don't critique my own work mercilessly, that I don't expect every piece of work to be better than the last, or that I am easily satisfied.

Now that I've gotten to the point (in this strange adventure I am calling a writing career) where other people are beginning to expect things of me, I'm really starting to have fun. I like few things better than a really high bar, except for maybe nudging it a little higher. I might whine or angst over it to my friends (poor Justine), but really, it drives me.

It has absolutely nothing to do with competing with other people. I don't actually care that much about that. Other people can do their thing, and I'll do mine. Some will do and be objectively better, others won't. Some are flatly more talented, others aren't. That stuff ... meh. It is what it is. All that drives me is what I can control, and the only thing I can control is how hard I work.

So ... when I don't meet those expectations ... you know what? I'm pretty forgiving of myself (most of the time). I usually just buckle down and work harder. But really, when it's something I care about, and when I really feel like I've done all I can, I try to re-evaluate the goal I set for myself, and question whether or not it was reasonable. I usually don't waste time beating myself up, because that doesn't help me.

Enough about me! How about you? Where do your expectations come from? Who sets your bar? What happens when you don't quite reach it?

OH! And the winner of the exclusive LARKSTORM deleted scene is Alleged Author! Congrats!

Published on January 18, 2012 03:39