Dirk Strasser's Blog, page 3

October 29, 2014

Does it really matter how a novel ends?

They say life is a journey, not a destination. Can the same be said about a novel? How important is the ending in a work of fiction? How important is the telling along the way?

They say life is a journey, not a destination. Can the same be said about a novel? How important is the ending in a work of fiction? How important is the telling along the way?My initial reaction to this question would be to say, a work of fiction should be an organic whole, and you can’t really love the book unless you love the ending. How a book finishes is how you end up viewing the book, and because the ending is the last thing you read, it stays with you and colours everything else.

Here are some of the most famous endings from speculative fiction (including a few spoilers):

He loved Big Brother.

–Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell

I am Legend.

–I am Legend, Richard Matheson

He was soon borne away by the waves and lost in darkness and distance.

–Frankenstein, Mary Shelley

“How strange are the ways of the gods!” he gasped. “How cruel.”

–Soldier of the Mist, Gene Wolfe.

Good-bye and hello, as always.

–The Courts of Chaos, Roger Zelazny

Overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.

–“The Nine Billion Names of God”, Arthur C Clarke

I have no mouth. And I must scream.

–“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”, Harlan Ellison

A LAST NOTE FROM YOUR NARRATOR

I am haunted by humans.”

–The Book Thief, Markus Zusak

He climbed in and fitted the thole pins into the oarlocks, and after three strong strokes he was well out onto the face of the river. And as he rowed on, toward whatever might prove to be the true destiny of the man who'd been Brendan Doyle and Dumb Tom and Eshvlis the cobbler and William Ashbless, and was not any of them any longer, he regaled the river birds with every Beatles song he could remember... except Yesterday.

–The Anubis Gates, Tim Powers

P.S. please tel prof Nemur not to be such a grouch when pepul laff at him and he woud have more frends. Its easy to have frends if you let pepul laff at you. Im going to have lots of frends where I go.

P.S. please if you get a chanse put some flowrs on Algernons grave in the bak yard.

–Flowers for Algernon, Daniel Keyes

How do these compare to some of the classic endings outside the genre:

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

–The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

“The offing was barred by a black bank of clouds, and the tranquil waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth flowed sombre under an overcast sky – seemed to lead into the heart of an immense darkness.”

–The Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

“It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

–A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

There’s no doubt a poor ending ruins the reading experience and will cause a reader to be disappointed in the book even if they had enjoyed it up until then. But what happens if the ending is just okay? Does an ending have to be great for the book to be great?

I don’t think the answer to this question is as obvious as it seems. Let’s have a look at a series none of us yet know the ending of: George R R Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire/ Game of Thrones. Are we going to judge this series by its ending? Does it really matter which of the many options Martin has left open is the one he will ultimately choose? I doubt if he’ll choose a stinker of an ending, but after so much intrigue and drama and surprises, won’t we most likely feel just a little flat no matter what he picks? And if we do, will his choice somehow negate everything that’s appeared in the seven (or eight) books?

Is it possible that sometimes a work is so good an ending can’t possible live up to it? Kafka said that past a certain point in a novel, a writer could decide to finish the work at any moment, with any sentence, claiming it was like deciding where to cut a piece string. This may have some truth to it when it comes to character-driven novels, but surely it can’t apply to plot-driven novels? Or maybe it applies to literary novels rather than genre novels?

Then I started thinking about a number of my favourite writers and their works. Stephen King, for example, is one of the most successful writers of all time, but even his biggest fans would agree that most of the endings in his novels are pretty weak. His strengths are in the things he does along the way. How he portrays terror and tension, how he builds different elements into a powerful story, the characters, the relationships between children and adults, and his evocation of the time and place where he grew up. However, despite all this, his books often just limp home at the end.

Philip José Farmer’s Riverworld series has every person who ever lived suddenly being resurrected on the banks of a giant river. The series explores the interactions of different historical figures and cultures. It’s a fascinating work, but the eventual explanation of who is doing this and why almost inevitably has to be a letdown because the setup is so brilliant. I get a similar feeling with James Dashner’s Maze Runner series. To me the revealed reasons the boys are in the maze are far less compelling than the story of how they seek to make sense of the situation they find themselves in. The journey is greater than the destination.

If you still think that a book can only be great if it has a great ending, think about how often you’ve ever recommended a novel by saying, you’ve got to read this because it’s got a great ending.

Published on October 29, 2014 18:37

September 29, 2014

I know what I like - but is it any good?

We all like to think we’re good judges of fiction. It’s easy to make assertions about how good (or bad) a particular novel is, but when we say “this is really good”, are we really saying anything more than “I like this”?

We all like to think we’re good judges of fiction. It’s easy to make assertions about how good (or bad) a particular novel is, but when we say “this is really good”, are we really saying anything more than “I like this”?What makes a work of fiction good? It’s a simple question that doesn’t have a simple answer.

A while ago Hugh Howey, best-selling author of Wool, said this as part of an article analysing author earnings:

Consider the three rough possibilities for an unpublished work of genre fiction:

The first possibility is that the work isn’t good. The author cannot know this with any certainty, and neither can an editor, agent, or spouse. Only the readers as a great collective truly know…

The second possibility for a manuscript is that it’s merely average. An average manuscript might get lucky and find an agent. It might get lucky a second time and fall into the lap of the right editor at the right publishing house. But probably not. Most average manuscripts don’t get published at all. Those that do sit spine-out on dwindling bookstore shelves for a few months and are then returned to the publisher and go out of print…

The third and final possibility is that the manuscript in question is great. A home run. The kind of story that goes viral… When recognized by publishing experts (which is far from a guarantee), these manuscripts are snapped up by agents and go to auction with publishers. They command six- and seven-figure advances. The works are heavily promoted, and if the author is one in a million, they make a career out of their craft and go on to publish a dozen or more bestselling novels in their lifetime.

Hugh Howey’s main argument in this article was about self-publishing, but what struck me was how easily he categorised works of fiction into “not good”, “average” and “great” as if these were easily verifiable categories. His assumption was that no individual on their own (regardless of how well-read they were, or whether they were publishing industry professionals or not) can be certain that something is good. He is saying that this knowledge can only come from the great mass of readers as a collective group. The people as a whole decide what’s good.

Is this true? Is the best book the one valued highly by the most people? How do you measure what the mass of readers view is a great book? I’m not quite sure what Hugh intended here, but is he equating “best” with “best-seller”? Does this mean, for example, that the best (not just best-selling) novel in 2012 was Fifty Shades of Grey? That can’t be right, can it? Or is the best book the one with most positive reviews? Or the best positive vs negative review ratio? Or the most downloaded or bought, regardless of price? How do we know there isn’t some masterpiece that everyone will instantly love which isn’t languishing somewhere through lack of marketing or by being over-priced or because it’s written in an obscure language that has relatively few speakers?

The issue is complicated even further by the fact that people’s tastes change. Works considered the best in a period in the past would often not find much of an audience if they were published for the first time today. I know many people who say The Lord of the Rings starts off much too slowly for them. They want more action. Even in more recent times, publishing trends wax and wane. Steampunk novels used to be “great” not so long ago, and now they seem to be considered just “good”. I’ve read articles that say paranormal romance and urban fantasy is not as popular as it used to be and epic fantasy is having a resurgence. “Goodness” is supposed to be an eternal quality, isn’t it? If “goodness” is somehow determined by the vagaries of taste and fashion, does the concept have any meaning?

Is there ever a true consensus about whether a work of fiction is good? Often a sort of group-think comes into play when a work becomes a mega-seller. People read something because other people have read it, and so on, and the book’s status becomes self-generating. But even in the case of these fabulously selling books, there is often a backlash against the work after it has reached a certain level of popularity, where a substantial group argue it’s grossly over-rated. Whose opinion is more valid?

Of course, the most valid opinion of all is the one that agrees with yours!

A version of this post first appeared in Aurealis #74 and on Insane about Books. End-of-year free subscriptions to Aurealis are currently available.

Published on September 29, 2014 23:02

August 4, 2014

What's Predicting the Future got to do with Science Fiction?

Gardner Dozois, one of science fiction’s leading editors, is reported to have said that a good science fiction writer who notices the car and the cinema should go on to predict the drive-in—and then go on to predict the sexual revolution. He was arguing that science fiction isn't simply about predicting new technology or scientific advances, it's also about exploring the social consequences of those developments.

Gardner Dozois, one of science fiction’s leading editors, is reported to have said that a good science fiction writer who notices the car and the cinema should go on to predict the drive-in—and then go on to predict the sexual revolution. He was arguing that science fiction isn't simply about predicting new technology or scientific advances, it's also about exploring the social consequences of those developments.Those who look in at science fiction from the outside focus obsessively on the narrow predictive qualities of science fiction, and make their judgements on the quality of a work based on the accuracy of the predictions. That's obviously a nonsensical criterion for a work of fiction. For one thing, if this was the criterion, then you would need to potentially reserve your judgement on a work for centuries. You wouldn't be able to say a novel was any good until you could see how well the author foresaw the future, as if SF writers were really just fortune-tellers.

Here are some of the successful predictions attributed to science fiction writers which I've had a stab at ranking in terms of significance of prediction:

1. Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 (1953) predicted earbud headphones, describing them as 'little seashells… thimble radios' that brought an 'electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talk'.

2. Aldous Huxley predicted antidepressants in Brave New World (1931) with soma, the mood-altering medicine that kept people sane.

3. Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward (1888) predicted 'universal credit' where citizens spent credit from a central bank on goods and services without paper money changing hands.

4. Hugo Gernsback's Ralph 124c 41+ (1925, serialised from 1911) predicted video-conferencing, radar, television, channel surfing, remote-control power transmission, transcontinental air service, practical solar energy, synthetic milk and foods, artificial cloth, voice-printing, tape recorders, and spaceflight.

Ray Bradbury's novel is universally lauded as a masterpiece, while Hugo Gernsback's novel is usually derided as a work of fiction and almost no-one reads it anymore. Yet the level of prediction in Fahrenheit 451 is trivial compared to Ralph 124c 41+. In these examples, the quality of prediction is actually inversely proportional to the literary merit. The better the prediction, the lousier the fiction! (Sorry, Hugo, at least you had an award named after you.)

You might argue that I've made a specific selection to back up my point. Maybe, but whatever the case, I don't think you can reasonably argue that the higher the quality of the prediction in science fiction, the higher the quality of the fiction.

I think we can all reasonably conclude that we're never going to be invaded by Martians, but that doesn't diminish H G Wells' The War of the Worlds . I can't wait to see whether gorillas and chimpanzees take over the planet so that I can decide whether I've enjoyed Planet of the Apes or not.

Let's not allow those outside of the science fiction to place value criteria on SF that has nothing to do with good writing. Science fiction explores futures and possibilities, but its worth doesn't lie in the accuracy of the speculation. I would argue that what good science fiction writers do isn't predicting the future, but influencing it. Before something new can come into being, someone has to imagine it first. So, not only could science fiction writers be responsible for the drive-in, they could also have some responsibility for the sexual revolution!

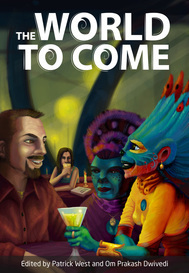

The international science fiction anthology The World To Come, to be launched later this month, is as much about influencing the future as it is about predicting the future. Twenty-one writers from around the world speculate on what is just around the corner for us all. My story "2084" appears for the first time in English, and I sincerely hope I don't have to wait 70 years for people to be able to tell me if it's any good or not.

The World To Come anthology will be launched by author, film-maker, and former 60 Minutes journalist, Jeff McMullen as part of the Melbourne Writers Festival on Sunday 31 August 2.30 pm at ACMI The Cube, Federation Square, Melbourne. The session will also feature an exploration of new trends in short fiction by the co-editor of the anthology, Patrick West, and several authors.

A version of this article appeared in Aurealis #73.

Aurealis half-year subscriptions are free until the end of August.

Published on August 04, 2014 21:01

July 3, 2014

Zenith eBook Giveaway guarantee!

Everyone entering the Zenith Giveaway in the last 24 hours will be guaranteed to win an eBook copy of Zenith – The First Book of Ascension (available as pdf, epub or Kindle files). Enter the draw below.

a Rafflecopter giveaway “Dirk Strasser’s Zenith… is on my list of all-time worldwide Top Ten fantasy novels… It does what all good quest novels do, and does it better than almost any of them – that is, it creates wonders.”

“Dirk Strasser’s Zenith… is on my list of all-time worldwide Top Ten fantasy novels… It does what all good quest novels do, and does it better than almost any of them – that is, it creates wonders.”

Richard Harland, author of Worldshaker

"Strasser’s unique blend of adventure, esotericism, Eastern mysticism, and fantasy makes for compelling reading… Strasser has not just written down a legend, rather, he has crafted one."

Amazon review

a Rafflecopter giveaway

“Dirk Strasser’s Zenith… is on my list of all-time worldwide Top Ten fantasy novels… It does what all good quest novels do, and does it better than almost any of them – that is, it creates wonders.”

“Dirk Strasser’s Zenith… is on my list of all-time worldwide Top Ten fantasy novels… It does what all good quest novels do, and does it better than almost any of them – that is, it creates wonders.”Richard Harland, author of Worldshaker

"Strasser’s unique blend of adventure, esotericism, Eastern mysticism, and fantasy makes for compelling reading… Strasser has not just written down a legend, rather, he has crafted one."

Amazon review

Published on July 03, 2014 02:44

Zenith eBook Giveaway!

Momentum is giving away 20 eBook copies of Zenith – The First Book of Ascension (available as pdf, epub or Kindle files). Enter the draw below.

a Rafflecopter giveaway “Dirk Strasser’s Zenith… is on my list of all-time worldwide Top Ten fantasy novels… It does what all good quest novels do, and does it better than almost any of them – that is, it creates wonders.”

Richard Harland, author of Worldshaker

"Strasser’s unique blend of adventure, esotericism, Eastern mysticism, and fantasy makes for compelling reading… Strasser has not just written down a legend, rather, he has crafted one."

Amazon review

a Rafflecopter giveaway “Dirk Strasser’s Zenith… is on my list of all-time worldwide Top Ten fantasy novels… It does what all good quest novels do, and does it better than almost any of them – that is, it creates wonders.”

Richard Harland, author of Worldshaker

"Strasser’s unique blend of adventure, esotericism, Eastern mysticism, and fantasy makes for compelling reading… Strasser has not just written down a legend, rather, he has crafted one."

Amazon review

Published on July 03, 2014 02:44

June 24, 2014

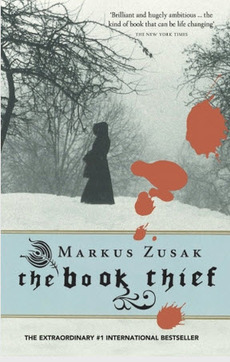

Is The Book Thief fantasy?

I know what some of you are thinking in response to my question. Does it matter whether Markus Zusak's

The Book Thief

can be classified as fantasy or not? A good book is a good book (and I do think this is a good book). Why put a label on it? Why does it matter how we categorise it?

I know what some of you are thinking in response to my question. Does it matter whether Markus Zusak's

The Book Thief

can be classified as fantasy or not? A good book is a good book (and I do think this is a good book). Why put a label on it? Why does it matter how we categorise it? It matters because fantasy is often still seen as an embarrassing distant cousin by the literary establishment, an attitude based entirely on ignorance where the worst examples are cited as proof rather than the best. The view is that fantasy can't be important and profound the way real literature is; it is trivial and of no consequence in the world of letters.

The Book Thief is both important and profound. It has been incredibly popular. It is literature.

It is also fantasy.

What other conclusion can you possibly come to about a book whose narrator is Death? This element of the book isn't a minor side-show. I was afraid at first that it was going to be simply a device to make the novel appear more literary, or that it was for shock value at the start and the narrator would soon become irrelevant to the story. I was wrong on both counts. The narrator ends up being integral to the power of the novel. The Book Thief is one of those rare books where its quirks and unusual techniques draw you further into the story rather than throw you out of the world being created. The writing has a haunting simplicity. How can The Book Thief be anything but fantasy when one of the narrator's most striking lines is: "I'm haunted by humans"?

Published on June 24, 2014 18:30

June 1, 2014

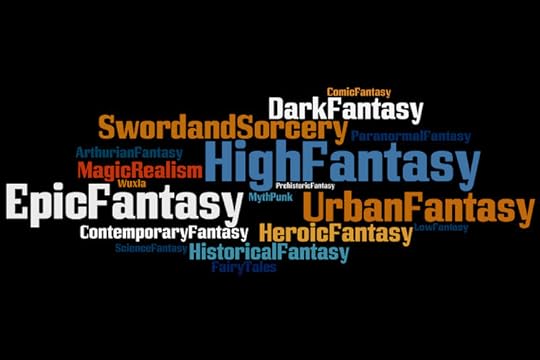

What sort of fantasy is that?

The question I most dread coming from publishers about my fantasy work is: “What other novels would you say yours is like?” It means that, despite their best efforts, they haven’t been able to categorise what I’ve written. And if they can’t put it in a box and stick a label on it, they can’t sell it.

The question I most dread coming from publishers about my fantasy work is: “What other novels would you say yours is like?” It means that, despite their best efforts, they haven’t been able to categorise what I’ve written. And if they can’t put it in a box and stick a label on it, they can’t sell it.The fiction publishing game is an art form, not a science. In spite of claims by some people, you can’t really predict what will be successful or how something will sell. All a publisher can do is try to find something similar to a new work and claim that this new work will sell at the same levels. Sometimes this pays off. Sometimes it doesn’t. However, this approach gives a publisher nowhere to go when faced with a work that defies comparison.

This practice of seeking comparisons is magnified with fantasy. There are so many sub-genres now. You can’t just label yourself simply as a fantasy author. Do you write urban fantasy or paranormal romance? Horror or dark fantasy? High fantasy or epic fantasy?Steampunk or New Weird? And there are even more avenues of comparison In fantasy, such as the supernatural creature you’ve focused on. Is yours a ghost story? A unicorn tale? Dragons were in for a while, then lost favour, but now could be on their way back again to claim the treasure that is rightfully theirs. Vampires are still hanging on in there despite recent overexposure. Werewolves seem to be eternally roaming around on the periphery, and not quite in the centre of publishing. Zombies are remarkably persistent – they just keep on coming at you with those dead eyes.

So how do I answer that publisher question about what I would compare my novels to? I usually have to fudge the answer by picking the best selling fantasy author I can think of and qualifying the comparison. My novel’s like George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones, I would say, but with more likeable characters and genuine romance (which is, of course, saying it’s not like Game of Thrones at all, so I’m not lying). Or it’s like The Lord of the Rings but with strong female characters. Or it’s Harry Potter without the wizards.

What I would really like to do to answer the question is to create my own unique fantasy sub-genre labels for my novels. I would love to be able to say The Books of Ascension are “mystic fantasy”, that is, fantasy infused with eastern mysticism that involves the uncovering of deep secrets. I could also coin the term “sand and sorcery” to categorise my Seven Prophets series to suggest it’s sort of like “sword and sorcery” but set in the desert and drawing on Arabian Nights mythology. My middle grade fantasy series The Guardians of Wyrland could be pigeon-holed as “suburban fantasy”, where fantastical elements encroach on an average middle-class suburb.

I can’t be the only one who wants to create their own unique marketing labels for their work. If I’m going to be put in a box, I want to make the box myself so that it’s comfortable, and allow myself enough wriggle room so that I can get out.

So, what sort of fantasy do you write?

Artwork: "Berth" by James Morgan

Published on June 01, 2014 23:12

May 19, 2014

She spooned the soup from her bowel – the joys of typos!

This bowl typo appeared in a close-to-final draft of my fantasy novel, Zenith. Unfortunately, spellcheck won't pick up an error like this. Even more unfortunately, I didn't pick it up. I was lucky because a friend of mine saw it on a read-through and had a good laugh at my expense.

You've got to ask yourself: why did I write it, and after I’d written it, why didn't I pick this up? I know the difference between bowl and bowel – and why you would want to spoon something out of one, but not the other. I guess typos happen because typists are human, and it’s only human to make mistakes.

One theory puts a lot of typos down to the “fat-finger syndrome” where your fingers hit two keys at the same time on a keyboard or two buttons together on a touch screen. That could have been the case with my bowel typo – the “w” and “e” are next to each other on a QWERTY keyboard.

Simply trying to write something too quickly is another reason for typos. Recent Search Engine Optimization research has indicated that misspellings probably occur in around 10% of search queries. Typo-squatters actually use this to make money by registering a possible typo of a well-known website address hoping to get traffic when internet users mistype that address into a web browser. Or even more sneakily, they deliberately put typos into a webpage or its metadata so that search engines direct people who make this error to the site.

Here are some typos that obviously didn’t make it through the checking processes.

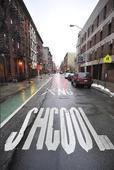

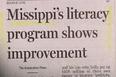

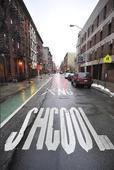

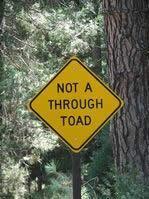

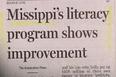

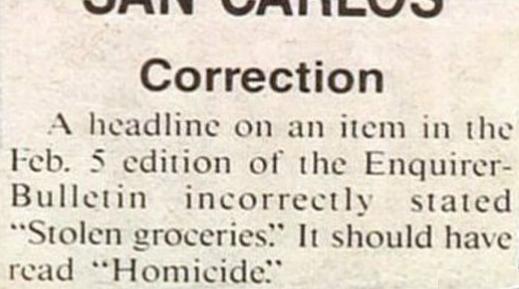

These two prove that no word is saef from the typo-bug:

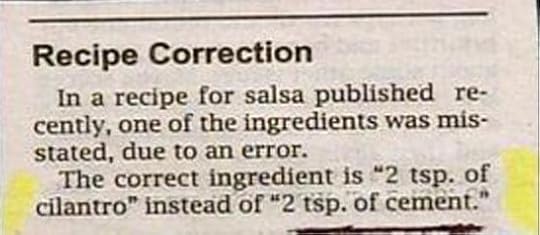

Sometimes, it’s just one letter that makes the difference:

Sometimes, it’s just one letter that makes the difference:

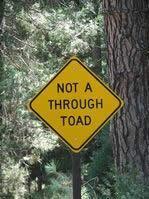

Sometimes it’s two letters:

Sometimes it’s two letters:

“Germans are so small that there may be as many as one billion, seven hundred million of them in a drop of water.” – Mobile Press US

“I have a graduate degree in unclear physics.” – job application

Sometimes writers should really hang their heads in shame:

Well, does we?

Well, does we?

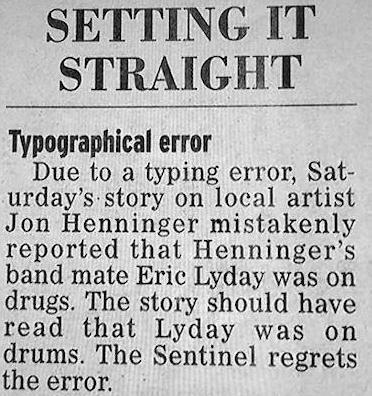

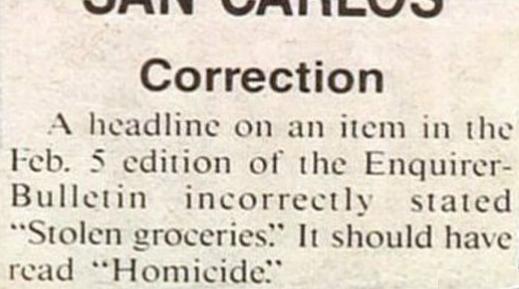

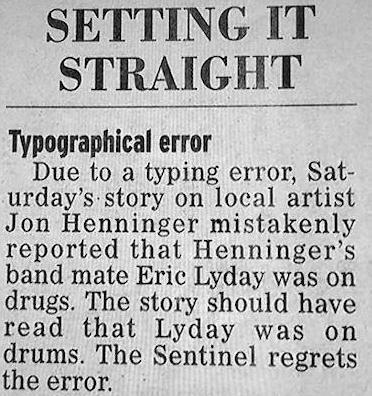

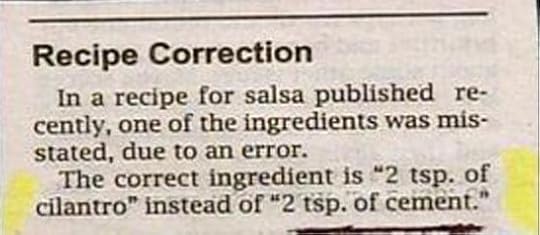

Sometimes the correction is funnier than the original typo:

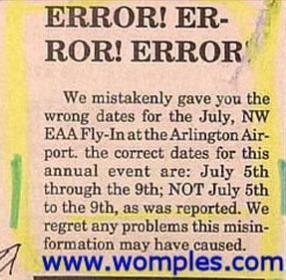

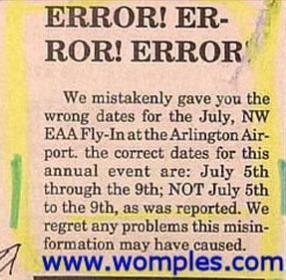

Sometimes the typo correction has a typo correction:

Sometimes the typo correction has a typo correction:

Typos are funny things. Thank goodness for editrs.

Typos are funny things. Thank goodness for editrs.

This first appeared as a guest blog on The Right Book For You.

You've got to ask yourself: why did I write it, and after I’d written it, why didn't I pick this up? I know the difference between bowl and bowel – and why you would want to spoon something out of one, but not the other. I guess typos happen because typists are human, and it’s only human to make mistakes.

One theory puts a lot of typos down to the “fat-finger syndrome” where your fingers hit two keys at the same time on a keyboard or two buttons together on a touch screen. That could have been the case with my bowel typo – the “w” and “e” are next to each other on a QWERTY keyboard.

Simply trying to write something too quickly is another reason for typos. Recent Search Engine Optimization research has indicated that misspellings probably occur in around 10% of search queries. Typo-squatters actually use this to make money by registering a possible typo of a well-known website address hoping to get traffic when internet users mistype that address into a web browser. Or even more sneakily, they deliberately put typos into a webpage or its metadata so that search engines direct people who make this error to the site.

Here are some typos that obviously didn’t make it through the checking processes.

These two prove that no word is saef from the typo-bug:

Sometimes, it’s just one letter that makes the difference:

Sometimes, it’s just one letter that makes the difference:

Sometimes it’s two letters:

Sometimes it’s two letters:“Germans are so small that there may be as many as one billion, seven hundred million of them in a drop of water.” – Mobile Press US

“I have a graduate degree in unclear physics.” – job application

Sometimes writers should really hang their heads in shame:

Well, does we?

Well, does we?Sometimes the correction is funnier than the original typo:

Sometimes the typo correction has a typo correction:

Sometimes the typo correction has a typo correction: Typos are funny things. Thank goodness for editrs.

Typos are funny things. Thank goodness for editrs.This first appeared as a guest blog on The Right Book For You.

Published on May 19, 2014 23:54

April 30, 2014

The World to Come is coming!

Published on April 30, 2014 19:58

March 25, 2014

The Top 5 Reasons why People say they hate Fantasy (and why they're wrong)

There are two types of people in the world: those that love fantasy and those that haven't given it a proper go. Here are the 5 top reasons why people say they hate fantasy (and why they're wrong):

There are two types of people in the world: those that love fantasy and those that haven't given it a proper go. Here are the 5 top reasons why people say they hate fantasy (and why they're wrong):1. Fantasy has characters with silly names. Yep, main characters' names don't get any sillier than Bilbo, Tyrion and Harry. They should be Billy-Bob, Timmy, and... er... Hugh.

2. Evil creatures who inflict pain on others shouldn't be ludicrously labelled Nazgûl, White Walkers or Dementors. They should be demons, devils and dentists.

3. Dark Lords shouldn't be called dumb names like Sauron, Morgoth or Voldemort, and should instead be called by their accurate sensible-sounding names: Satan, Lucifer and Beelzebub.

4. You can make anything happen in fantasy (which is different to other types of fiction where you can only write about things that have actually happened).

5. Fantasy makes you escape from reality (whereas other types of fiction allow you to go through all your real-life activities while simultaneously holding a book in your hand and reading).

Published on March 25, 2014 22:45

The international science fiction anthology The World To Come , edited by Om Dwivedi (India) and Patrick West (Australia), which includes my story "2084", published for the first time in English, will be available in July.

The international science fiction anthology The World To Come , edited by Om Dwivedi (India) and Patrick West (Australia), which includes my story "2084", published for the first time in English, will be available in July.