Dirk Strasser's Blog, page 2

November 9, 2018

The Magic of Portal Books

We all have books that we read when we were younger and which led us into fantasy or science fiction or whatever genres we choose to spend the bulk of our time reading as adults. These are often called gateway books, those novels that opened up reading for us. While some of my gateway books into fantasy include staples such as The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings and the Narnia series, I would also count a handful of more obscure books as my way into fantasy in particular. I suspect we all have some of these lesser known books in our reading past that have had a profound influence on us.

We all have books that we read when we were younger and which led us into fantasy or science fiction or whatever genres we choose to spend the bulk of our time reading as adults. These are often called gateway books, those novels that opened up reading for us. While some of my gateway books into fantasy include staples such as The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings and the Narnia series, I would also count a handful of more obscure books as my way into fantasy in particular. I suspect we all have some of these lesser known books in our reading past that have had a profound influence on us.I think of these as portal books. A gate is a public entrance, a way in that everyone is aware of. Some of us may choose not to enter, but there’s no denying its renown. It’s there for everyone to see, bold and unforgettable. Like Babylon’s Ishtar Gate or the Golden Gate of Byzantium or the Meridian Gate to the Forbidden City. But whereas a gateway is public, drawing attention to itself, portals are hidden, only visible to the few—and that’s often where the truly profound magic lies. It’s these sorts of books that reveal most about us. While gateway books are those we share with others, portal books are more personal—they divulge our uniqueness. We rarely talk about them because others will most likely not have read, or even heard of, them.

One of my portal books was so buried in my past I couldn’t even remember the name of it. (By coincidence, it also featured a type of portal as a plot device.) It was by British author E (Edith) Nesbit. Her most famous novel is The Railway Children, but this well-known book had little impact on me and I barely remember reading it. At around age eleven I scoured my local library for E Nesbit books. I found many of them a little disturbing. She didn’t write like the other authors I’d read. There was an edge to it I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Perhaps I’d now call it a hint of the grotesque, a slightly off-kilter frisson. The novel I remember most powerfully, the one that I would nominate as my key portal book, was about a dirt-poor crippled orphan boy in Edwardian London who mysteriously travels to an alternative world 300 years earlier where he’s a healthy son of a nobleman. The story didn’t pivot around predictable plotlines. I haven’t re-read it since, but I remember the boy moved between the two periods several times until it got to a point where he had to make a choice. I remember being floored by his freely-made decision to stay in the world where he was dirt-poor and crippled because he was needed there. The novel was called

Harding’s Luck

.

One of my portal books was so buried in my past I couldn’t even remember the name of it. (By coincidence, it also featured a type of portal as a plot device.) It was by British author E (Edith) Nesbit. Her most famous novel is The Railway Children, but this well-known book had little impact on me and I barely remember reading it. At around age eleven I scoured my local library for E Nesbit books. I found many of them a little disturbing. She didn’t write like the other authors I’d read. There was an edge to it I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Perhaps I’d now call it a hint of the grotesque, a slightly off-kilter frisson. The novel I remember most powerfully, the one that I would nominate as my key portal book, was about a dirt-poor crippled orphan boy in Edwardian London who mysteriously travels to an alternative world 300 years earlier where he’s a healthy son of a nobleman. The story didn’t pivot around predictable plotlines. I haven’t re-read it since, but I remember the boy moved between the two periods several times until it got to a point where he had to make a choice. I remember being floored by his freely-made decision to stay in the world where he was dirt-poor and crippled because he was needed there. The novel was called

Harding’s Luck

.It’s usually relatively easy to pinpoint how gateway novels have affected you. The influence of portal books, by their nature, is harder to tie down. I’ve only recently realised the connection between this book and my latest novel, which while having a totally different setting, structure and feel to Harding’s Luck, is about portals and the crucial decisions they force on people.

I don’t expect too many of you to have read Harding’s Luck, and I suspect its life as a potential portal book is over. Younger readers these days will probably baulk at the Edwardian street language, and for those of us older readers, the time for gates and portals into reading will never return. You can quite easily find Harding’s Luck online these days. But of course, it doesn’t matter whether or not you’ve read it. You all found your own portals.

This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #115.

Published on November 09, 2018 21:20

Is Fantasy & Science Fiction the Most Popular Genre?

So how does fantasy & science fiction compare to other fiction genres? Is its popularity trending up or down? My hunch based on my experiences in the industry would have been it was in the top two (or maybe three) most popular genres—but then I could be biased in my thinking because I write speculative fiction, read more speculative fiction than any other genre, and co-edit the speculative fiction magazine, Aurealis. I’m in contact with like-minded people daily. It’s easy to over-emphasise how widespread something is under those circumstances. Hunches are all well and good, but I decided to hunt up some recent statistics.

So how does fantasy & science fiction compare to other fiction genres? Is its popularity trending up or down? My hunch based on my experiences in the industry would have been it was in the top two (or maybe three) most popular genres—but then I could be biased in my thinking because I write speculative fiction, read more speculative fiction than any other genre, and co-edit the speculative fiction magazine, Aurealis. I’m in contact with like-minded people daily. It’s easy to over-emphasise how widespread something is under those circumstances. Hunches are all well and good, but I decided to hunt up some recent statistics.It proved quite tricky to do.

A survey of US readers by Statista last year asked people which genres they read regularly. These were the results. As you can see, people could nominate more than one genre.

Crime & Thriller 59%

Adventure 47%

Classics 44%

Fantasy 43%

Historic 42%

Romance 42%

Science Fiction 42%

Literature 40%

Horror 26%

Erotica 12%

Other 8%

Don’t know 1%

I don’t have access to the methodology or raw data behind this, but what struck me was that the top genre ‘Crime & Thriller’ was the only ‘double-barrelled’ category in the survey. I suppose it’s a natural association to combine the crime genre with the thriller genre, even though not every crime novel is a thriller, and not every thriller is a crime novel. However, wouldn’t the combining of fantasy & science fiction into one category for the purposes of this survey have been at least as natural? Most of the bookstores I’ve been to over the years pair the two. It’s been argued by some that fantasy & science fiction are both part of the continuum of speculative genre fiction. Others have maintained that genres should be defined by the primary emotion they intend to evoke, and that both fantasy & science fiction are part of what should be called the Wonder Genre. There’s even a line of argument that science fiction is actually a subset of fantasy. Whatever, the case, the two are clearly closely linked.

So what would the result have been if they had been classed as the one ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ category within the survey. Clearly, since the respondents were allowed to give more than one answer, you can’t simply add the two percentages together, but there’s no doubt combining the two results would have changed the results considerably, most likely putting ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ at number two, possibly even number one. It all comes down to how many people in the survey said they read science fiction regularly but not fantasy and vice versa.

2017 survey by the Australia Council for the Arts and Macquarie University gives us some insight into the relative popularity of a combined ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ category. In this survey, people were asked to nominate their number one favourite adult fiction genre (that is, they couldn’t list more than one, so we can’t compare it directly to the Statista survey).

2017 survey by the Australia Council for the Arts and Macquarie University gives us some insight into the relative popularity of a combined ‘Fantasy & Science Fiction’ category. In this survey, people were asked to nominate their number one favourite adult fiction genre (that is, they couldn’t list more than one, so we can’t compare it directly to the Statista survey).Their results were as follows:

Crime/Mystery/Thrillers 32%

Science Fiction & Fantasy 22%

Contemporary/General Fiction 14%

Romance 7%

Historical 6%

Classics 6%

Literary 3%

Graphic Novels, Manga & Comics 3%

Horror 2%

Erotica 2%

This one has a triple-barrelled category as the most popular. Interestingly, it focused solely on adult fiction titles, so it deliberately excluded Young Adult/New Adult titles which are often also read by adults and which have a high proportion of fantasy & science fiction titles.

It’s usually worth digging past the headlines of a statistical-based announcement. Statistics are incredible useful and a crucial part of modern life, but they can be misleading if they are naively interpreted. For example, industry statistics and publishing professionals have been reporting for years that since 2010 print sales for fantasy & science fiction have halved.

It’s usually worth digging past the headlines of a statistical-based announcement. Statistics are incredible useful and a crucial part of modern life, but they can be misleading if they are naively interpreted. For example, industry statistics and publishing professionals have been reporting for years that since 2010 print sales for fantasy & science fiction have halved.This belief was debunked at the 2018 SFWA Nebula Conference in a presentation based on data collected by www.authorearnings.com. It provided evidence that when ebooks and audio books are taken into account, traditional publishers are currently selling more adult fantasy & science fiction than ever before. Furthermore, in 2017, 48% of fantasy & science fiction bought in the US were non-traditionally published books. So in reality, instead of fantasy & science fiction numbers halving since 2010, as is often claimed, they have in fact doubled.

Just to add further evidence that there’s a boom in fantasy & science fiction, in 2018 Aurealis magazine has had its most successful year since going digital-only with a 41% increase in paying subscribers.

Here's to the boom!

This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #116.

Published on November 09, 2018 20:10

October 1, 2018

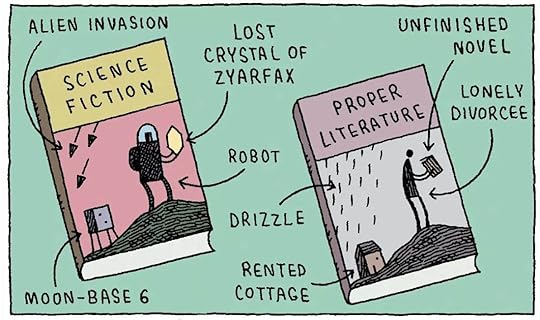

The Genre Effect - How Literary Readers are Biased Against Science Fiction

For those of you who don't know, I co-edit a fantasy and science fiction magazine called Aurealis. A number of years ago, when Aurealis was a print-only magazine, we regularly applied for grants from various government bodies such as the Australia Council and Arts Victoria. We were competing for funding with well-established literary magazines such as Meanjin, Overland and Quadrant. The funding always went directly to increasing author payment levels, so we felt it was worth the effort. It was always a difficult and time-consuming process to fulfil all the requirements of an application. We were successful on five occasions, but we also had a long string of unsuccessful applications. The biggest sticking point was always the requirement to demonstrate ‘literary merit.’ Surely only a reading of the stories can demonstrate that.

For those of you who don't know, I co-edit a fantasy and science fiction magazine called Aurealis. A number of years ago, when Aurealis was a print-only magazine, we regularly applied for grants from various government bodies such as the Australia Council and Arts Victoria. We were competing for funding with well-established literary magazines such as Meanjin, Overland and Quadrant. The funding always went directly to increasing author payment levels, so we felt it was worth the effort. It was always a difficult and time-consuming process to fulfil all the requirements of an application. We were successful on five occasions, but we also had a long string of unsuccessful applications. The biggest sticking point was always the requirement to demonstrate ‘literary merit.’ Surely only a reading of the stories can demonstrate that.But that’s where a magazine of fantasy and science fiction is at a distinct disadvantage.

At the end of 2017 the results of a research project called The Genre Effect study were published in the journal Scientific Study of Literature. It was undertaken by Professors Chris Gavaler and Dan Johnson from Washington and Lee University.

Around 150 participants were given a text of 1000 words to read. Half were given a ‘literary’ version of the text and the other a ‘science fiction’ version. The texts were identical except in the literary version, the main character enters a diner while in the science fiction version, he enters a galley in a space station inhabited by aliens and androids as well as humans. The only differences between the two were setting-related. For example, the literary version used the word ‘door’ and the science fiction version used the word ‘airlock.’

After the reading, the participants were asked to comment on the literary merit of the story they had read. They were asked how much effort they spent trying to work out what the characters were feeling, and how much they agreed with statements such as ‘I felt like I could put myself in the shoes of the character in the story.’

The study exposed a self-fulfilling bias among literary readers against science fiction, demonstrating that science fiction is currently still unfairly viewed in academia.

Here are some of the results from the study:

‘Converting the text’s world to science fiction dramatically reduced perceptions of literary quality, despite the fact participants were reading the same story in terms of plot and character relationships.’ The readers of the science fiction version generally scored lower in comprehension. They ‘reported exerting greater effort to understand the world of the story, but less effort to understand the minds of the characters.’

The professors also reported that readers of the science fiction version of the story ‘appear to have expected an overall simpler story to comprehend, an expectation that overrode the actual qualities of the story itself… the science fiction setting triggered poorer overall reading and appears to predispose readers to a less effortful and comprehending mode of reading—or what we might term non-literary reading—regardless of the actual intrinsic difficulty of the text.’

Professor Gavaler says, ‘those who are biased against SF, thinking of it as an inferior genre of fiction, they assume the story will be less worthwhile, one that doesn’t require or reward careful reading, and so they read less attentively… It’s a self-fulfilling bias—except we can now show objectively that the weakness is with the reader, not the story itself.’ He adds, ‘if you’re stupid enough to be biased against SF you will read SF stupidly.’ He is interested in exploring this Genre Effect further and discovering whether fantasy tropes such as a sorcerer’s wand would have similar effects on readers.

These results are not a surprise to those of us who have been involved in science fiction publishing over the years and explains the issues we had when applying for grants in the past. As Professor Gavaler says, while it’s disappointing that these biases exist, at least now they’ve been exposed.

A version of this article appeared in Aurealis #114 .

Published on October 01, 2018 21:28

September 6, 2018

The Top 4 Current Trends in Science Fiction

I was on a panel at

Speculate

, the Speculative Writers Festival, earlier this year ambitiously titled ‘Science Fiction: The Past, the Present, and What’s to Come’. I was charged with presenting a 10-minute introduction to the present trends in science fiction. It proved quite a challenge to wrestle the vast amorphous mass that is the science fiction currently being written into some recognisable pattern. The days have long gone when a single person could read even a sizeable percentage of all the science fiction produced in a calendar year. And making the task even more difficult was the fact that trends are usually only clear in retrospect.

I was on a panel at

Speculate

, the Speculative Writers Festival, earlier this year ambitiously titled ‘Science Fiction: The Past, the Present, and What’s to Come’. I was charged with presenting a 10-minute introduction to the present trends in science fiction. It proved quite a challenge to wrestle the vast amorphous mass that is the science fiction currently being written into some recognisable pattern. The days have long gone when a single person could read even a sizeable percentage of all the science fiction produced in a calendar year. And making the task even more difficult was the fact that trends are usually only clear in retrospect.Nevertheless I gave it a go.

Because of the panel’s specific focus and the nature of the festival audience—and to try to make the task slightly more manageable—I concentrated specifically on what could be fairly unambiguously defined as science fiction as opposed to fantasy, on the written word rather than movies and television series, and on novels rather than short stories. Since the festival was aimed at writers of speculative fiction, I looked for patterns in what was big in the science fiction of today—what was hitting the bestsellers lists and what was winning awards.

So what big trends did I uncover? There were four.

The first was Climate Fiction, that is, fiction that deals with climate change, often in a post-apocalyptic or dystopian future. The interesting thing about cli-fi, to use the slightly dismissive abbreviation commonly used, is that it is taken seriously by the mainstream. The literary establishment has embraced it, and it gets reviewed in the mainstream press. People base their PhDs on it. It has status as ‘literature’ and isn’t dismissed the way a lot of science fiction still is.

The first was Climate Fiction, that is, fiction that deals with climate change, often in a post-apocalyptic or dystopian future. The interesting thing about cli-fi, to use the slightly dismissive abbreviation commonly used, is that it is taken seriously by the mainstream. The literary establishment has embraced it, and it gets reviewed in the mainstream press. People base their PhDs on it. It has status as ‘literature’ and isn’t dismissed the way a lot of science fiction still is.While the literary establishment has recently discovered cli-fi and bestowed a sense of worthiness on it, Climate Fiction has, of course, been around for some time as part of the science fiction landscape. Australian author George Turner wrote the quintessential cli-fi novel well before it was a recognised subgenre of science fiction. His The Sea and Summer (The Drowning Towers in the US) was set in a world where global warming had resulted in a Melbourne landscape that was largely underwater. It was published in 1987 and won the Arthur C Clarke Award and was nominated for a Nebula.

Climate Fiction is making an impact in the major SF awards. Out of the six Hugo Finalists for Best Novel this year, two were clearly cli-fi: New York 2140, by Kim Stanley Robinson and The Stone Sky, by N K Jemisin (technically science fantasy). Other major Climate Fiction novels in recent years include Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife. Three recent Aurealis Awards Finalists also fall into the category: Clade by James Bradley, Lotus Blue by Cat Sparks, and Daniel Findlay’s Year of the Orphan.

The second trend was the New Space Opera. ‘Space opera’ was originally a somewhat disparaging name, deriving from a comparison with ‘soap operas’ and suggesting grand, melodramatic themes. It involved large-scale, fast-paced science fiction adventure featuring space warfare, alien races and intelligent machines. Often it had a military aspect to it, although the main character focus was on civilians. Brian Aldiss once said, ‘Science fiction is for real, space opera is for fun.’

The second trend was the New Space Opera. ‘Space opera’ was originally a somewhat disparaging name, deriving from a comparison with ‘soap operas’ and suggesting grand, melodramatic themes. It involved large-scale, fast-paced science fiction adventure featuring space warfare, alien races and intelligent machines. Often it had a military aspect to it, although the main character focus was on civilians. Brian Aldiss once said, ‘Science fiction is for real, space opera is for fun.’

The New Space Opera is still fun on a grand scale, set in space, exciting, fast-paced, but it’s also usually more scientifically rigorous, more literary, has more emphasis on character development, and addresses social issues of race, gender, class and postcolonialism. The term was coined in the 2007 anthology The New Space Opera edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan. Notable novels that fall into this subgenre are Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice winner of the 2014 Hugo Best Novel, Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion, Yoon Ha Lee’s The Raven Stratagem, a Best Novel Finalist in this year’s Hugos, and The Expanse series by James S A Corey. The New Space Opera has also been invading Young Adult books with such novels as Illuminae by Amie Kaufman and Jay Kristoff, the 2015 Aurealis Award Best SF novel winner.

The third trend I identified was Generation Ship Fiction which focuses on sub-lightspeed starships that take several human generations to arrive at their destination, where the original occupants grow old and die, leaving their descendants to continue travelling. Unlike works relying on faster-than-light (FTL) travel, this subgenre is based on the more rigorous extrapolation of current science where FTL speed is impossible. The closed environment of a generation ship has proven to be a particularly versatile story vehicle, allowing powerful explorations, ranging from sustainability-based dilemmas and breakdowns in social structures to murder mysteries. Recent examples include Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson, Neal Stephenson’s SevenEves, and Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty, a 2018 Hugo Best Novel Finalist.

The third trend I identified was Generation Ship Fiction which focuses on sub-lightspeed starships that take several human generations to arrive at their destination, where the original occupants grow old and die, leaving their descendants to continue travelling. Unlike works relying on faster-than-light (FTL) travel, this subgenre is based on the more rigorous extrapolation of current science where FTL speed is impossible. The closed environment of a generation ship has proven to be a particularly versatile story vehicle, allowing powerful explorations, ranging from sustainability-based dilemmas and breakdowns in social structures to murder mysteries. Recent examples include Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson, Neal Stephenson’s SevenEves, and Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty, a 2018 Hugo Best Novel Finalist.

Gender-focused Science Fiction was the fourth trend I found. These works deal with gender identity and involve depictions of single gender or genderless societies. Like all the other trends, it’s not new, but it has become increasingly prominent in recent times. It’s a trend that is often combined with one of the other three trends. The obvious precursor is the multi-award winning The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin, published in 1969. Two New Space Opera novels I’ve already mentioned clearly also fall into this subgenre: Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion and Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice. Recent Australian Gender-focused Science Fiction has included From the Wreck by Jane Rawson, which won the 2017 Aurealis Awards for Best SF Novel and An Uncertain Grace by Krissy Kneen, which was an Aurealis Awards Finalist in the same year.

Gender-focused Science Fiction was the fourth trend I found. These works deal with gender identity and involve depictions of single gender or genderless societies. Like all the other trends, it’s not new, but it has become increasingly prominent in recent times. It’s a trend that is often combined with one of the other three trends. The obvious precursor is the multi-award winning The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin, published in 1969. Two New Space Opera novels I’ve already mentioned clearly also fall into this subgenre: Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion and Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice. Recent Australian Gender-focused Science Fiction has included From the Wreck by Jane Rawson, which won the 2017 Aurealis Awards for Best SF Novel and An Uncertain Grace by Krissy Kneen, which was an Aurealis Awards Finalist in the same year.

Of course, for writers, identifying trends isn’t much more than the first step. The crucial question is to what extent (if at all) should a writer take these trends into account. That’s something to explore another time.

This blog appeared in a different form as an Editorial in Aurealis #113.

Published on September 06, 2018 19:10

March 14, 2017

Celebrating Aurealis #100 in print!

What better way to celebrate our hundredth issue of Aurealis – Australian Fantasy & Science Fiction than to publish

Aurealis #100

as a limited edition print issue (in addition to the usual digital version). Aurealis #100 will be much bigger than our normal issue, with eight stories, three articles, plus book reviews. In fact, it will be our biggest ever single issue.

What better way to celebrate our hundredth issue of Aurealis – Australian Fantasy & Science Fiction than to publish

Aurealis #100

as a limited edition print issue (in addition to the usual digital version). Aurealis #100 will be much bigger than our normal issue, with eight stories, three articles, plus book reviews. In fact, it will be our biggest ever single issue.We decided to go back to everyone that was still contactable who appeared in Aurealis #1 in 1990 and ask them for a story for this hundredth issue. Plus there are some surprises. Here's the Contents list:From the Cloud 1 — Dirk StrasserFrom the Cloud 2 — Stephen HigginsFrom the Cloud 3 — Michael PryorThe Cavity -- David TanseyShimmerflowers -- Michael PryorThe Mandelbrot Bet -- Dirk StrasserThe Bewitching of Dr Travidian -- Geoffrey MaloneyThe Madlock Chair -- Terry DowlingAll We Have is Us -- Alex IsleForest/Trees -- Stephen HigginsMayfire -- Rebecca BirchThe History and Future of Aurealis: An Interview with Dirk Strasser — Chris LargeRobotics, AI and the Impending Techno-Apocalypse — Terry WoodSecret History of Australia--Archibald Cistoon—Researched by Michael PryorReviews

Aurealis #100 will be launched at the Science for Science Fiction conference (Sunday 30 April 2017 8:30 am – 5:00 pm at 8 La Trobe Street Melbourne) which The Royal Society of Victoria is running in partnership with Aurealis magazine (and supported by the Emerging Writer's Festival).

It’s a conference for new and established authors of science fiction where you can learn valuable writing techniques and draw inspiration from real scientists such as Dr Alan Duffy, regular guest on

The Project

who was named as one of Australia's Science Superheroes by the Australia’s Chief Scientist.

It’s a conference for new and established authors of science fiction where you can learn valuable writing techniques and draw inspiration from real scientists such as Dr Alan Duffy, regular guest on

The Project

who was named as one of Australia's Science Superheroes by the Australia’s Chief Scientist.  All those attending will get a free print copy of Aurealis #100. For those of you who want to make sure you get a copy of the limited print run, you can order Aurealis #100 now, and have it mailed to you at the end of May.

All those attending will get a free print copy of Aurealis #100. For those of you who want to make sure you get a copy of the limited print run, you can order Aurealis #100 now, and have it mailed to you at the end of May.

Published on March 14, 2017 20:48

March 2, 2016

Following the Elevenpath

You can’t control a work of fiction after it’s been published. Once it has found a readership, it belongs to the readers as much as it belongs to the writer. I was made profoundly aware of this some time ago in relation to my own writing when I came across an online German article Lucid Dreaming that featured an interview with a musician called Till Oberbossel. Here’s my translation of the last question and response from the interview:

You can’t control a work of fiction after it’s been published. Once it has found a readership, it belongs to the readers as much as it belongs to the writer. I was made profoundly aware of this some time ago in relation to my own writing when I came across an online German article Lucid Dreaming that featured an interview with a musician called Till Oberbossel. Here’s my translation of the last question and response from the interview:You’re a widely read fantasy nerd and have read many series in English. So, apart from the well-known ones such as Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, etc, which do you think are good and why?

I enjoy reading and love fantasy, although I also read across many other areas. As far as fantasy is concerned, Tolkien's works and, of course, the Chronicles of Prydain are my favourites. It’s hard coming up with reasons for my preferences. If a novel or series grips me I don’t usually try to work out why. If I feel comfortable in the fantasy world, I stay there like a while. Apart from the ones I’ve mentioned, the others I’ve really enjoyed are: the Conan stories of Robert E Howard, the Books of Ascension trilogy by Dirk Strasser (by the way, there will be a song on the next Elvenpath album based on this), the Death Gate Cycle series by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, and not least the Discworld novels by Terry Pratchett. I love them dearly. Thanks for the interview, for your interest in Lucid Dreaming and allowing me to present my music here… Support the Underground and stay Metal!

Whoa! I did a double take. The words ‘there will be a song on the next Elvenpath album based on this’ really floored me. A song based on my trilogy? Wow! Something I had written had actually inspired a musician to write a song. I knew the Books of Ascension had been published in German in 2001, but for the series to percolate in someone’s mind all this time and to emerge in musical form is mind-boggling.

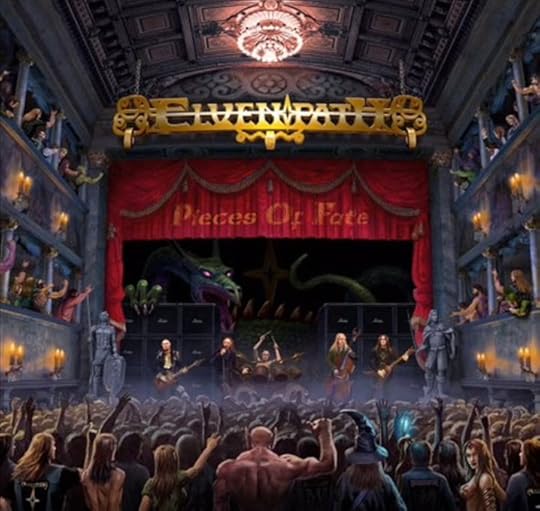

I contacted Till via his band’s website to wish him luck and saying I would love to hear the song. He seemed almost as surprised to hear from me as I was to see my trilogy mentioned in his interview. He sent me the lyrics and a copy of the Elvenpath CD Pieces of Fate when it was released in 2015.

So, what sort of music is inspired by fantasy fiction? The only music I was aware of was the acoustic, lyrical, floating-through-the-ether sort of melodies. This band’s elvenpath is completely different. Their music is power metal. So for those of you who aren’t familiar with the term (as I wasn’t when I first came across it—AC/DC is about as metal as I’ve ever been): power metal is type of heavy metal with an elevating anthem-like sound. Like the epic fantasies that inspires it, power metal strives for an epic sound. If Elevenpath are typical, then the vocalists can sing in a high register and have a wide range, and the guitarists have a high level of technical proficiency.

And above all their lyrics are in synch with high fantasy sensibility. They are both evocative and powerful. Here’s an example from Mountain of Sorrows , the song based on the Books of Ascension:

When night conquers the daylight and winter calls our names

Our roads will differ, will fate be the same

Storms cross my pathways, pillars of stone

And many a strange sight I see

Puppets and demons, warriors and masks

They reveal the dark side to me

Cloisters of silence, houses of life

The mountain is standing, who knows what’s inside

Amazone warriors attack in the night

The hour has come when steel will shine bright

Mountain of sorrows, grown of fear and lies

I’ll climb you forever though blood be the price

Mountain of sorrows, made of doom and fraud

Beware the ascension of him who’ll be god

The lyrics are potent and poetic. None of these words are mine, yet they have grasped the essence my novels. There’s no doubt Till Oberbossel gets fantasy. And to write this sort of stuff in what isn’t his first language takes impressive skill.

If you had told me all those years ago when I started to write Zenith—The First Book of Ascension, that a power metal band from Frankfurt, Germany, would be opening their new album with a song based on my work, I would have bet my house on it not happening. You just can’t tell what sort of life your fiction will lead once you’ve given birth to it.

If you like epic fantasy, have a listen to Elvenpath’s Mountain of Sorrows, Battlefield of Heaven and Queen Millennia from the Pieces of Fate album. And remember. Stay Metal!

This first appeared as an Editorial in Aurealis #88.

Published on March 02, 2016 03:06

February 4, 2016

People aren’t Orcs

Traditionally high fantasy has been the battleground between good and evil. At the centre of the conflict is the personification of the ultimate evil: The Dark Lord, the Shadow, Sauron, Morgoth, Voldemort, He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named. But the Dark Lord usually doesn’t engage in battle directly. He leaves this to his minions. Creatures born of evil are the Dark Lord’s foot soldiers: Orcs, goblins, Uruk-Hai, trolls and balrogs. And who usually lines up against them? Humans. Often conflicted humans. People who are noble and brave, but also cowardly and corruptible. People who are wise but can also be foolish. People who need to find the best in themselves to defeat the ultimate evil. It’s not hard to see why this sort of fantasy has come to dominate popular culture. Who can resist the ultimate battle? Who doesn’t want to see the Dark Lord defeated? The stakes are higher in high fantasy than in any other literature.

Traditionally high fantasy has been the battleground between good and evil. At the centre of the conflict is the personification of the ultimate evil: The Dark Lord, the Shadow, Sauron, Morgoth, Voldemort, He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named. But the Dark Lord usually doesn’t engage in battle directly. He leaves this to his minions. Creatures born of evil are the Dark Lord’s foot soldiers: Orcs, goblins, Uruk-Hai, trolls and balrogs. And who usually lines up against them? Humans. Often conflicted humans. People who are noble and brave, but also cowardly and corruptible. People who are wise but can also be foolish. People who need to find the best in themselves to defeat the ultimate evil. It’s not hard to see why this sort of fantasy has come to dominate popular culture. Who can resist the ultimate battle? Who doesn’t want to see the Dark Lord defeated? The stakes are higher in high fantasy than in any other literature.Serious problems, however, occur when the concepts underpinning the high fantasy battleground start to leach into real life; when the equivalents of Dark Lords and Orcs make their way into politics. In September 2015, former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott got himself into all sorts of trouble speaking about ‘different levels of evil’ when comparing IS behaviour with historical atrocities. That was on top of his analysis of the Syrian civil war as ‘It’s not goodies versus baddies, it’s baddies versus baddies!’

Of course, the prince of the high fantasy approach to real world problems was the US President George W Bush, when, in his State of the Union address, he first identified the ‘Axis of Evil:’ Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. He went on to make many high fantasy references during his presidency, including

‘The evil ones have roused a might nation, a mighty land.’ 12 November 2001

‘We're determined to fight this evil... We act now, because we must lift this dark threat from our age and save generations to come.’ 6 November 2001

‘Our struggle is going to be long and difficult. But we will prevail. We will win. Good will overcome evil… we are fighting evil, and we will continue to fight evil, and we will not stop until we defeat evil.’ 2 November 2001

‘This will be a monumental struggle of good versus evil. But good will prevail.’ 12 September 2001

In April 2003, the US Government passed up Iran’s proposed concessions, which included making peace with Israel, saying ‘We don’t speak to evil.’ Really? Iranians are evil? Created that way like Orcs, as a perversion of humanity by the Dark Lord?

History is littered with people who have done appalling things, totally convinced that they are right. The problem with treating people like Orcs is that it bestows the moral right to do absolutely anything to them. To be ruthless in unconditional certainty. No discussion. End of story.

But it shouldn’t be the end of the story.

We should all heed the warning sirens any time a politician starts talking about evil. Don’t let it go unchallenged. Real life isn’t high fantasy. It’s not hard to keep the two separate. None of us has been created by a Dark Lord. People aren’t Orcs. #PeopleArentOrcs

This blog appeared as an Editorial in Aurealis #87.

Published on February 04, 2016 03:14

December 26, 2015

Who's hijacking speculative fiction?

A few years ago one of the major banks in Australia ran a series of advertisements which featured time travelling. It involved a number of people meeting their future selves and being congratulated by them for wise investment decisions they had made. I remember these advertisements annoyed me intensely. It took me a while to work out why I was reacting so strongly. I finally came to the conclusion that they irritated me so much because I felt that the speculative fiction genre was being sullied by being used by large corporations to manipulate people for commercial gain. Time travel is one of my favourite sub-genres and to see its emotional impact and resonance being used to increase bank profits was offensive.

A few years ago one of the major banks in Australia ran a series of advertisements which featured time travelling. It involved a number of people meeting their future selves and being congratulated by them for wise investment decisions they had made. I remember these advertisements annoyed me intensely. It took me a while to work out why I was reacting so strongly. I finally came to the conclusion that they irritated me so much because I felt that the speculative fiction genre was being sullied by being used by large corporations to manipulate people for commercial gain. Time travel is one of my favourite sub-genres and to see its emotional impact and resonance being used to increase bank profits was offensive.I’ve since come across speculative fiction tropes and references everywhere in the general media. I’ve seen articles in the financial pages of major newspapers referring to “my precious” in relation to market motivations and “winter is coming” in terms of a slide in economic indices. Really? Is that what the power of fantasy and science fiction should be used for? To comment on the Dow Jones?

I guess we should be flattered. The Eye of Sauron is now everywhere. Speculative fiction was once seen as a ghetto – a glorious golden ghetto, but a ghetto nonetheless. A place where outcasts eeked out an existence. A dark corner for the literary impoverished, the room under the stairs for the writers and readers who couldn’t breathe in the mainstream.

That has all changed. Speculative fiction has transformed into humanity’s overarching narrative. Our genre has not just become the mainstream, it is now the prism through which the world is seen.

In a Time magazine article earlier this year, Lev Grossman wrote:

Something odd happened to popular culture somewhere around the turn of the millennium… somewhere around 2000 a shifting of the tectonic plates occurred. The great eye of Sauron swivelled, and we began to pay attention to other things. What we paid attention to was magic. … Fantasy wasn’t a fringe phenomenon anymore. It had become one of the great pillars of popular culture and, increasingly, the way we tell stories now.

Maybe we should be cheering that we’ve won, that we’ve cast our spell over the muggles and they now all see what we’ve always seen. And yet, somehow I feel if we’re not careful we’re in danger of being subsumed by corporate wraiths who want to use the magical power for their own evil ends. To make all of us do things we wouldn’t otherwise choose to do. To cast a spell to sell their products. To make us believe things that aren’t true.

Let’s be vigilant and call out when speculative fiction is being used to manipulate. The genie might be out of the bottle, but hopefully we can find the right words for the spell to shove it back.

A version of this appeared in Aurealis #86.

Published on December 26, 2015 16:47

November 2, 2015

Where have all the aliens gone?

Everyone loves a good alien story, don’t they? Or is that just me? Some exotic planet with an alien species so strange we human interlopers completely misunderstand their motives and actions. Or where the aliens themselves act on a misinterpretation of our intentions with disastrous consequences. I recently started to wonder whether aliens were becoming extinct.

Everyone loves a good alien story, don’t they? Or is that just me? Some exotic planet with an alien species so strange we human interlopers completely misunderstand their motives and actions. Or where the aliens themselves act on a misinterpretation of our intentions with disastrous consequences. I recently started to wonder whether aliens were becoming extinct.

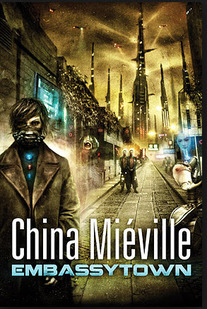

I remember reading some mind-blowing exotic planet / inscrutable alien novels years ago, but there just don't seem to be as many around these days, and the ones that are getting published don't seem as mind-blowing as they once were. Full marks to China Miéville for coming up with high-level inscrutable aliens a few years ago in Embassytown . The enigmatic Ariekei spoke a language that requires two words to be spoken at the one time. The problem for me was the Ariekei were so alien, I couldn’t warm to them. I guess that was the idea, but it didn’t quite bring back to me the wow-factor that I felt reading some of the older works.

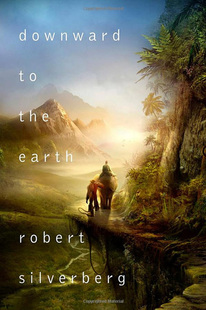

I was beginning to wonder if it was me. Had I become jaded or would I still enjoy the aliens from the past? I decided to put it to a test. The most exotic planet and inscrutable aliens I can remember from my early reading was Robert Silverberg’s

Downward to the Earth

. They don’t write ‘em like that any more! Not one but two sentient species, with a strange mutual relationship that humans couldn’t figure out. Huge elephant-like nildoror and human-like but brutish sulidoror who were clearly subservient to the more intelligent species. And all of this on a planet dripping with exotica: jungles with parasitic fauna so far off the bizarre scale you need to come up with a new word to describe them, mysterious mist regions from which humans were banned travelling for unfathomable reasons, and an enigmatic protagonist who has returned to make up for the sins he committed during his first stay during the planet’s colonial past.

I was beginning to wonder if it was me. Had I become jaded or would I still enjoy the aliens from the past? I decided to put it to a test. The most exotic planet and inscrutable aliens I can remember from my early reading was Robert Silverberg’s

Downward to the Earth

. They don’t write ‘em like that any more! Not one but two sentient species, with a strange mutual relationship that humans couldn’t figure out. Huge elephant-like nildoror and human-like but brutish sulidoror who were clearly subservient to the more intelligent species. And all of this on a planet dripping with exotica: jungles with parasitic fauna so far off the bizarre scale you need to come up with a new word to describe them, mysterious mist regions from which humans were banned travelling for unfathomable reasons, and an enigmatic protagonist who has returned to make up for the sins he committed during his first stay during the planet’s colonial past.So I reread Downward to the Earth with a little trepidation. Was the meld of brooding beauty, mysterious motivations and grotesquerie still there? I more than half-expected I’d be disappointed and was a little surprised when I again felt the full brunt of its exotica. I was again immersed in the sheer alien-ness of the world and its two species. And the full force of the story had, if anything, even more impact. I was unaware of the Heart of Darkness allusions first time around, but on this reading they gave it more depth. For me the protagonist now seemed far more complex, his motives more tortured, the climax more profound. The world is the most vivid I’ve seen in science fiction. I can only hope that this Silverberg masterpiece finally makes it to the screen.

At least I know now it’s not that I’ve changed or that these stories have lost their power. The exotic aliens haven’t been pushed into extinction. I’m looking forward to discovering some more life forms.

A version of this appeared in Aurealis #85.

Published on November 02, 2015 16:44

December 25, 2014

So many books, so little time!

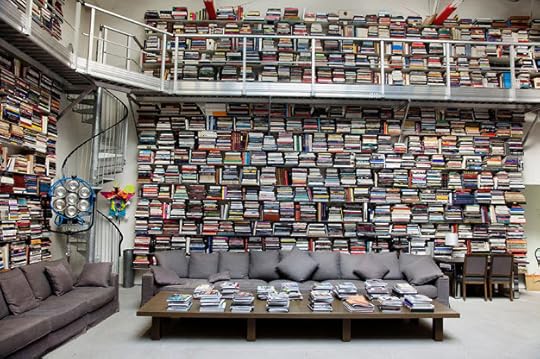

Ever felt overwhelmed by the sheer number of books on your “to-read” pile? If you really want to feel the weight of unread books on your shoulders, try working out the actual number of books you’ll simply never get to read in your lifetime, no matter how quickly you read.

Ever felt overwhelmed by the sheer number of books on your “to-read” pile? If you really want to feel the weight of unread books on your shoulders, try working out the actual number of books you’ll simply never get to read in your lifetime, no matter how quickly you read.I don’t think my actual reading speed is slow, but I don’t get through anywhere near as many books as some of the avid readers I’ve come across. Maybe I’m unusual, but I like to savour books. I don’t want the good ones to end, so I tend not to whip through them in a couple of days. I’ve never read a book in one sitting. But the main reason is I simply don’t have the time or the energy. Other things often get in the way of sustained reading, and my eyes just won’t stay open for that long at night after a typical exhausting day. I know a number of people who consistently get through several books a week. I’m afraid my average would be several weeks per book.

Of course, it’s not a competition, but I sometimes wonder about all the great books I’ll probably never get to read. Is that true of everyone? Even the most voracious reader can only skim the surface of the massive depths of published books.

Here are some staggering facts about the number of books being published. As reported in the recent Frankfurt Book Fair, Bowker’s “Books in Print” (which despite the name includes eBooks) estimates that the total number of books in print in English in 2013 hit 28 million. That’s right, 28 million! The report also states this involves approximately 9 million authors.

These figures calculated by Bowker are based on all the titles with ISBNs in the US, UK, Australia. What’s scary is that, in my view, this means the actual number is probably significantly higher. The Bowker calculation doesn’t cover all the English language publishing in the world in 2013. I’m not sure whether Bowker have extrapolated their figures, but clearly when you consider all the other English-publishing countries (such as Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and India) en masse, it suggests Bowker’s figures may be conservative. For example, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce has estimated that India is the world’s 3rd largest English language publisher.

There is another factor which may mean that Bowker’s 28 million estimate is probably too low. For books sold exclusively through Amazon’s Kindle store, you don’t need an ISBN – all that’s required is an Amazon-assigned ASIN number. Given the size of Amazon and its self-publishing program, this means a significant number of books haven’t been accounted for if only ISBNs were tallied.

And it’s not like this figure remains static. The pile of world books sitting next to our collective beds continues to grow each year. Again, according to a Bowker report, in 2013 in the United States alone, around 390,000 new ISBNs were taken by the self-published authors and 300,000 by the traditional publishers.

Does that make you feel better or worse about the books you haven’t read?

Published on December 25, 2014 15:57