Clémentine Beauvais's Blog, page 6

January 29, 2014

On voyeurism in children’s and YA literature

Breaking news: children’s and YA literature, especially the latter, can be pretty racy. From Tabitha Suzuma’s tale of an incestuous relationship between brother and sister (Forbidden) to The Hunger Games‘s murderous children, through to that scene in Melvin Burgess’s Junk where the heroin-addict mother punches a needle into her breastfeeding breast in search of a workable vein…

Breaking news: children’s and YA literature, especially the latter, can be pretty racy. From Tabitha Suzuma’s tale of an incestuous relationship between brother and sister (Forbidden) to The Hunger Games‘s murderous children, through to that scene in Melvin Burgess’s Junk where the heroin-addict mother punches a needle into her breastfeeding breast in search of a workable vein…

These are just three of dozens of texts where teenagers are raped, killed, torture, or do that unto others; or simply where sex scenes, even consenting and loving, are frankly explicit. Personally, I’ve got a horse in the racy race, or rather two, since my French YA books are so shocking than no UK publisher will publish them as YA. La pouilleuse narrates a day of psychological and physical torture perpetrated by a group of idle teenagers on a six-year-old girl. Comme des images goes through what happens after a video of a sixteen-year-old girl masturbating is leaked to the whole school. So no, I don’t have anything against racy YA.

There will always be people who say that it’s voyeurism. But this frequently-used term is often left undefined. As a result, it’s easy to retort that the person is just a prude, as if an accusation of ‘voyeurism’ was simply a glorified translation of ‘I’m shocked’, or ‘I can’t stomach this’. And it’s often the case, as there are indeed many watchful prudes in the children’s and Young Adult literature world.

Oh my goodness, the F-word!

But sometimes it’s a perfectly justified criticism. And the ‘other side’, the very vocal and active community of Young Adult writers and bloggers, too swiftly responds in terrifying torrents of Tweets to anyone who dares to criticise the work of one of their own.

And yet accusations of voyeurism, in the strictest sense of the word, aren’t necessarily idiotic or prudish or moralistic. They can be perfectly valid, and even important. But what does voyeurism actually mean?

Voyeurism doesn’t just mean ‘something shocking’, or ‘something with which some people might ideologically disagree’. Shocking the reader is good. Shocking the reader is a perfectly valid endeavour. What’s problematic about voyeuristic texts, from both an ideological and an aesthetic viewpoint, isn’t that they shock the reader, it’s that they trap the reader in a position from which s/he can’t escape; a position which forces him/her to feel pleasure, disgust, excitement, etc., when reading a specific scene.

This happens, for instance, in the case of:

Gratuitous episodes of sex, of psychological or physical violence, etc., which don’t add anything to the plot or characterisation but are there principally out of complacency, to elicit strong sensations in the reader.

Explicit descriptions that leave the reader no space to imagine what happens. Everything is said.

The (conscious or unconscious) desire to trigger sexual excitement in the reader, or a fascination for violence.

A lack of narrative distance towards what is represented, translated for instance as a unicity of narrative focalisation, or a narrative voice from which the reader has no way of detaching her/himself.

The choice of particularly ‘hot’ themes, such as child prostitution, forced marriages, teenage pregnancy, etc., mostly for their narrative potential, that is to say without taking into account the fact that real people experience these situations.

A lack of critical distance towards the ideological implications of the represented scenes or their symbolic meaning(s), or a representation which eludes unpleasant or questionable aspects to focus only on their sensationalism.

A lack of awareness of the generational gap between implied readers and implied author, and therefore a lack of awareness of the particular ethical and ideological issues linked to the representation, for instance, of extreme violence or of sex scenes; especially when those are ventriloquised by young characters behind which lurks, of course, an adult author.

Obviously, none of these elements is either sufficient or necessary to make a text voyeuristic, but it makes it more likely to fall into voyeurism.

The solution, of course, isn’t to eliminate controversial themes from Young Adult literature. I’d have to burn my own books. In fact I think that YA often doesn’t go far enough, in the sense that, even when it superficially engages with super-hot-themes, it often remains moralistic and conservative. Twilight is fairly racy, but it’s also, of course, hugely conservative. We need some more radical YA, and this radical YA must of course represent sex, violence, drugs. Those themes are not only attractive, they’re crucial to one’s understanding of existence, and literature can present and analyse them in different ways to our biggest ‘competitors’, film and video games.

So how can we write racy or violent scenes without falling into voyeurism? I’m not saying I’ve got an answer (I wish), but here are some thoughts:

Weakening the narrative voice. Voyeurism first and foremost establishes a relation of power between narratee and narrator. The reader must be able to rebel against what we’re forcing him/her to see: it’s only fair. On a narrative level, that means a narrator who isn’t omnipotent anymore. That means a voice that, even seemingly strong and assertive, reveals fault lines and hollow spaces. A narrative voice from which the reader can detach himself or herself, and actively seek a different vision of the scene.

Creating discomfort and unease. When we’re uneasy, it means we can’t fully be voyeurs. Voyeurism implies being mesmerised, adhering totally to what we see. Uneasiness, discomfort indicate that we are aware that, for some reason, we shouldn’t see what we’re seeing – and therefore we’re already judging what we’re seeing. An uneasy reader is a cleft reader, a divided reader, and therefore a questioning reader. Why am I feeling uncomfortable reading this? What isn’t right about this representation? You can’t fall into the trap of voyeurism when the text allows you to question what it’s giving you to see.

Being so outrageous the reader can’t see clearly anymore. Let’s be hyperbolic, lyrical, grandiose, excessive, disgusting, crude. If we’re going to shock the reader, let’s do it so it creates a screen so thick that the reader, try as they may, can’t even see what’s behind it. Nabokov lets Humbert Humbert say he wants to “turn [his] Lolita inside out and apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys”. This is the twelve-year-old girl he rapes “every night, every night”. Lolita is the story of an obsession for Lolita in which we can’t see Lolita anymore from the moment Humbert Humbert sets eyes on Lolita. Look as much as you want, you’ll never see her through the haze of that language. As a reader, you can’t enjoy her, you can’t delight in her; there’s nothing to see.

Not showing enough. This is the opposite strategy, of course: not giving enough to see. Punching holes through the text, disappointing the reader, not finishing what we started, forbidding climaxes. We can surprise the reader with a shocking paucity of details, insert endless, frustrating ellipses. And thus force the reader to become responsible for the text: to become responsible for his or her vision of things. Force the reader, therefore, to become empowered, active, inventive, and accountable.

Any other ideas? Thoughts? Disagreements?

If not, until next Wednesday, au revoir…

_______________________________________________

EDIT: This article was inspired to me by an interview in French where I was asked to respond to accusations of ‘voyeurism’ in my own works, so I wrote it mostly under my ‘creative writing hat’.

However, my ex-supervisor having noted that I tacitly appeared to refer to her own works in this article, I hasten to refer readers interested in the ramifications of this question for children’s literature criticism to the following:

The question of identification and of the importance of narrative voice in ‘trapping’ the young reader is tackled notably by Maria Nikolajeva in, among others, Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers (2010), and also by Maria Tatar in Enchanted Hunters, The Power of Stories in Childhood (2009).

Maria recently published an article on guilt in Forbidden and His Dark Materials which tackles the question of the overpowering narrative voice and the ethical problems it leads to in the adult-child relationship.

January 21, 2014

Some Royal News

Having read quite a few children’s books since I was born (they’re generally pretty good, you should try them), I recently became dissatisfied. Yes, dear readers, dissatisfied. Because none of them, no – none of the books I’d read ever gathered the following ten things all together in the same story:

Windsurfing starfish

Sextuplet princes (of toddlerish age) (crowns equipped with elastic bands)

A foreign king obsessed with blitz invasions (finished in time for dinner)

Hummingbird cannons

An amazing holiday including a trip to a Mars bar

A babysitting job paid one thousand pounds a day

A naked porcupine

A knitted parachute

A lift especially designed for a cow

A day of leave at the Independent Republic of Slough.

I was extremely sad about this oversight, because it appears to me that no children’s book can ever be quite complete without these ten things.

So I decided to write it!

And since other people agreed that the children’s literature world could not survive much longer without these ten things all neatly folded into a children’s book, it will be published as the first book in a series, by Bloomsbury, in September 2014!

(NB The lovely people at Bloomsbury, as a welcome present, having somehow heard from somewhere that I didn’t dislike one of their series, gave me this brand new Harry Potter box set -)

uh-oh, now I’ll have to reread them for the 67th time. Ah well!

The first volume of my own series, meanwhile, will be called The Royal Babysitters.

Based on a true story. (not)

What’s the pitch? Bickering sisters Anna and Holly, along with rather clueless little prince Pepino, have to look after six little princes for just one day – yes, but a day chosen by the bloodthirsty King Alaspooryorick of Daneland to invade the country.

A rather tough job, then, but you see, they have to earn some serious money to pay for the unbelievably cool Holy-Moly-Holiday that they’ve seen advertised in the newspaper. .

The second book in the series doesn’t have a name yet but it will be out in April 2015.

And it all takes place in a world… not quite like our own.

“But what age is it for?” asks the anxious adult. “From your description, it sounds like it could be for anyone between seven and a quarter and eight and a half! I need it to be more precise!!!”

It will be, I think, intended for children who are just getting to grips with the Art of Reading (well done them), though once again, like the Sesame books, I have written them carefully so they won’t immediately burn the neurons of anyone at a different stage of literacy.

And, what is supermuchmore exciting, it will be what I believe my friend and colleague Eve Tandoi would call a hybrid book series, that is to say a book where words and pictures both tell the story. It’s not quite a comic and it’s not quite a picturebook, but it’s somewhere in between, and I think it’s going to be hugely fun once the pictures are all drawn.

And it will be edited by none other than the extraordinary Ellen Holgate, who had already picked my Sesame at Hodder before moving to Bloomsbury. All those of you who’ve read Sesame books know how beautifully conceived and designed they are, so I’m ferociously excited that she’s working on the series too.

I hope you’re looking forward to it too. In fact I hope you’re now considering making lots of new babies in order to have an excuse to read them this series and then the Sesame Seade books. I’ll leave you to do that, then. I’ll just leave you to it.

Clem x

January 15, 2014

Starting a New Research Project

I’m starting a new research project!

OK, it’s the project for which I obtained my Junior Research Fellowship from lovely Homerton College, and said Fellowship started in October, so it was high time I began working on the new project. But I’ve had a monograph to write, as you may remember (yes, it’s almost done, yep, oh, thank you very much, that’s very kind of you, we’ll talk about it again when the peer-readers get back to me saying it’s a huge pile of rubbish), and courses to teach, and essays to mark, and books to read.

So the project had been pushed back until NOW. And NOW it’s really got to start because, well…

… because I’ve been invited to present some results from it at a symposium, erm, next, erm… year term month week.

WHAT?

YesIknow. ButIhaven’thadtime. Andwhoareyoutojudge. Anyway, that symposium is on a tiny part of what the new project entails. SO THERE.

My new project as a whole is about cultural and literary representations of child precocity. Nope, it’s not narrower than that yet; I haven’t even reached the narrowing-down stage, it’s that early. But I know it won’t be solely a children’s literature project; I’ll be foraying into other discourses (aw no don’t cry, I’ll still write about children’s books sometimes). I want to be able to jump from Matilda to Ada in the same sentence.

So how do you start researching something so vast? Frankly, I’m not completely sure. I’ve been thinking about it for months, and though thinking doesn’t technically count as research, it organises it. I’ve settled for a number of areas I need to investigate first to lay the foundations of the project.

Some of them I’m already familiar with (children’s literature, philosophy of childhood and education, sociology of childhood); others, less so.

One of them – psychological and sociological research about actual ‘precocious’ children – is completely outside my comfort zone. I don’t generally look at anything to do with real children (why on Earth would anyone). But I need to be able to analyse the discourses of these two fields of study, because scientific studies, discoveries and texts surrounding things contribute, of course, to social, political and cultural representations of those things.

Another one – ‘straight English’ scholarly research about representations of precocious children in literature ‘for adults’ – is, on paper, outside my current field, but I’m comfortable with it. The only danger I face is lack of legitimacy in the eyes of ‘straight English’ researchers, since most of them don’t think children’s literature scholars can actually read anything else than children’s literature (in fact, some doubt that we can even read children’s books). But my study will remain firmly within Childhood Studies, not English.

Finally, there’s another field I’ll need to get acquainted with – visual culture, which ranges from cinema to fine art. No biggie, right? I might eventually discard visual representations of precocious children if the task becomes too daunting, but it would be a shame, because there are so many of them. Again, it’s not my field at all.

Those disciplinary boundaries are a pain, because despite the emphasis laid on multidisciplinary research projects by universities, I don’t have the feeling that they are very popular among academics – especially people in very canonical disciplines. Philosophers, English Literature scholars, Historians don’t like it very much when other people dare to ‘do’ interdisciplinarity with ‘their’ discipline.

(They might look at your funny little hybrid subfield and tell you things about it (that you’ve known for twenty years), but the other way around is more controversial.)

Of course there’s always the danger that you might look like the person who pops into another office in the Ivory Tower and says ‘Do you mind if I borrow that tool of yours for a minute?’ having barely read the instruction manual, so the tool breaks, and whatever they were trying to operate with it breaks, and worse, they don’t even realise anything’s gone wrong.

Fingers crossed this won’t happen (too much) with this project. I have three years (well, two and two-thirds now) of full-time research that I can use to study those areas seriously and methodically, and acquire the legitimacy to branch into other fields of childhood studies (as well as, of course, to get to interesting conclusions about the whole of existence.)

Starting this new research project is looking a bit like walking into relatively hostile countries on a more or less forged visa, and pretending not to notice the locals’ suspicious glances. I’ll let you know if I manage to earn their trust while stealing their treasures.

January 6, 2014

A quarter of a century

I’m turning 25 today!

Therefore I’m officially a quarter of a century old, and, as Simone Weil politely told me this morning in my serendipitous current reading, “at twenty-five, it is high time to leave adolescence radically behind oneself…”

I think I’m fine with that, thanks – I hated being a teenager, and I was delighted to leave that bit of existence aside as soon as possible. But I thought a twenty-fifth birthday warranted a lightly self-reflexive blog post on the things I knew and didn’t know I’d do, at the then very old age of twenty-five, when I was a little girl.

And so, when I was a little girl…

When I was a little girl I would never have thought that, at twenty-five, I would be an academic.

I never imagined, until very, very late, that I’d become an academic. First I wanted to be a primary schoolteacher, then I wanted to work in publishing. I hated school. I told my mother, when I was ten or eleven years old, that I would quit school as early as the French system allowed – sixteen years old.

Fourteen years after that inflexible promise, I was out.

Even in my undergrad years, when I’d suddenly discovered, thanks to the UK system, that I loved studying, I didn’t think I’d stay on to do a Masters. Even during my MPhil, it took my supervisor to tell me “Just apply for PhD funding, you never know…”, and the aforesaid funding, for me to realise that this was indeed what I wanted to do more than anything else.

When I was a little girl, I would never have thought that at twenty-five, I would be childless(/free).

Until very late – 21, 22 years old, pretty much – I was convinced that I wanted to have children very early. The idea of being a young parent appealed to me greatly. I’d decided 23 was the perfect age to have a first child. Yep, 23. No idea why, but the arbitrary age was a firm decision.

As you may have noticed, I rarely talk on this blog about my two-year-old toddler. It’s because no such person exists.

Not only have I not fulfilled this youthful oath, but the idea of having children has never been farther from my mind than it is now. Complete change of heart, due, I think, to a variety of factors – some quite interesting, but matter for another blog post.

When I was a little girl, I would never have thought that at twenty-five, I would be constantly in touch with hundreds of people.

As a child and a teenager, I was quite solitary. I used to think I wasn’t very sociable, but I didn’t mind at all – I enjoyed the feeling of self-sufficiency it afforded me. I didn’t think I often met people with whom I felt on the same wavelength. I’d never have thought, of course, that with Facebook and blogs I would have the opportunity to meet and talk to hundreds of people who shared my interests, people with whom I would interact everyday, even though I might never meet them. On the French side, this is exactly what is happening, and I love it. These friendships and acquaintances are only virtual in their manifestations – not in their status. You learn so much, and are enriched so much, when you get in touch so easily with people who think about the same things as you do.

When I was a little girl, I already knew I would be a writer. But not exactly like this…

I always wanted to be a writer, and I never wanted to be a full-time writer. That’s done, but of course when I was a child I imagined something else. Immediately successful books, showers of awards and instant film adaptations. That’s normal for childish daydreams, I think.

But more importantly I never imagined that there would be this weird feeling of inadequacy regarding the books you publish, the constant, nagging impression that they’re not-quite-right, not what you meant – at all. Your name is on them and you sign them to people. But. There’s always something missing.

When I was a little girl, I already knew I’d always be interested in children’s literature and in childhood.

My interest in children’s literature and in childhood were always a part of my life. Even as a child, I was fascinated by childhood as a concept, even though of course I didn’t formulate it in that way. My own childhood, that of others. The passing of time, the end of childhood. Younger children fascinated me, too. I always devoured children’s books, regardless of age guidelines. As a teenager, I wanted to be a school teacher, but then I understood it was the theory that interested me. Not real children, but why adults (and me) were so obsessed with them, and with childhood. As I said, I’d never have thought I’d become an academic, but I knew that what I would do would be linked to childhood.

When I was a little girl, there were lots of other things I didn’t think I’d do at twenty-five years old.

Living in the UK, of course I couldn’t have foreseen that as a child – but as a teenager I started becoming interested by the English language and Britain. And other things were unexpected. I didn’t think I’d become so engrossed in philosophy one or two years after leaving France, where I’d received rigorous teaching in the discipline but also the impression that it was a dry and cold subject.

My personality has changed, of course. I’m more sociable and more accommodating now than I used to be. I feel much more balanced, less irritable, and less close-minded. But also much more stressed by the passing of time, the urgency of writing, reading, transmitting, learning, creating. I get bored less quickly, but each empty moment is oppressive – I’m more impatient than when I was a child.

And I hope the next twenty-five years are just as full of new opportunities, new discoveries, new books to read and to write, new friends. And at last my own home and an actual job (please!).

As well as more projects, which I see for now as fusing into ‘one’ project, that of thinking in different ways about childhood, always – that concept which still fascinates me even though I left childhood quite a while ago now, and that I’m less sentimental than I used to be about mine and that of others. If anything, it’s made it much more interesting.

December 17, 2013

So What?

My ex-PhD supervisor (who, by the way, is currently writing an amazing abecedary of children’s literature theory and criticism on her own blog) always says to her young Padawans that they must always ask themselves ‘So what?’ about everything they write. Ask yourself ‘So what?’ at the end of your article on ‘Representations of octopi in adventure stories for boys, 1870-1912′, for instance. If the answer is, ‘Well… octopi! in adventure stories!’ then your article is useless and you might as well have spent a month and a half painting the borders of your nostrils with glittery felt-tips.

The implication, of course, is that by asking ‘So what?’ you will attempt to truthfully decide whether your piece is parochial, petty and only concerned with what it attempts to describe (bad) or has wider implications, for the study of children’s literature for instance (good).

This is even more important in actual published work than it is in MPhil and PhD theses. As William Germano says in his book From Dissertation to Book (helpfully recommended by Philip Nel), one of the main differences between a PhD thesis and a monograph drawn from the PhD thesis is scope: while a PhD thesis investigates a tiny aspect of Problem X, the monograph should attempt to make claims about the whole of Problem X.

This was never a problem for me, however, because I am blessed with ridiculous theoretical arrogance. So my self-questioning always went along those lines:

Q. Piece of work finished. SO WHAT?

A. So, existence.

Q. Another piece of work finished. SO WHAT?

A. So, meaning of life.

Q. Another piece. SO WHAT, this time?

A. So, everything about everything.

Q. We are so nailing this ‘so what’ thing!

A. Yeah!

When I had my PhD viva, however, the questioning went along those lines:

Examiners: When you say ‘existence’ here, don’t you mean ‘that little aspect of existence that may or may not be there for everyone’?

Me: No, no, I do mean the whole of existence.

Examiners: Are you sure?

Me: What will happen if I say I’m sure?

Examiners: You’ll probably fail your PhD.

Me: Ah then I guess I’m not sure. In fact, I probably do mean that tiny little aspect of existence that may or may not be there for everyone.

Examiners: And when you say, there, ‘this is something which concerns the whole of children’s literature and in fact every instance of every address to a child, anywhere in the world and for the whole of history’, don’t you mean, ‘this is something that concerns some children’s books’?

Me: No, I…

Examiners: Think of what we just talked about.

Me: Yes, I mean that’s something that concerns just a few books here and there.

Examiners: Good. Do you promise not to make all these grand claims again in your monograph?

Me: Gnnhh.

Examiners: Swear on the life of J.K. Rowling.

Me: Gnnh.

It wasn’t the first time this happened. All my articles rejected from academic journals are generally accompanied by comments along the lines of ‘This is clearly the work of a deluded and vaguely despotic individual who makes hilariously grand claims about everything from the analysis of two lines of an obscure picturebook.’

So now that I’m working on the monograph, I’m going through it all and thinking about whether my answers to ‘So what’ are still absurdly grand or whether I can get away with them. Unfortunately the demon of grand theorisation often wins over the angel of scrupulous criticism.

that angel is so dumb #sodumb

And I do believe in those grand conclusions that I’m now editing down or rectifying. I didn’t just put them there as a forced reply to the question ‘So what?’. I honestly think that I have good reasons to be making those claims, and if these reasons aren’t clear to the reader, it means I’ve failed at explaining them, not that they weren’t there to start with. So I endlessly edit the explanations so they lead more clearly to the Theory.

I can’t help it, I have much more patience for grand systems, grand theories, outrageous hypotheses, than for microscopic examinations of quite interesting properties of some texts. At least the former can fail spectacularly, whereas the latter will only ever achieve an uninspiring sort of success.

Well, that’s what I like to think, anyway. I wouldn’t recognise myself in a piece of work, however conscientious, that wouldn’t have those grand answers to that ‘So what?’ question.

No, I wouldn’t recognise myself, and that’s why this ‘So what’ question pertains to so much more than just research. I can’t just ask ‘So what?’ of individual pieces of writing. I also need to ask myself ‘So what?’ about the relevance of that writing to my own life. So what? Why am I doing this? What is the point? Is my existence being transformed by what I’m researching and writing? It very much is and very much has been, as I think it should.

‘So what?’ isn’t just a professional question about the impact of your research on the rest of the discipline. It’s a private question, one that interrogates your life project. What you research is a part of yourself, so what? So it must have an impact on you. The boundaries can’t ever be clear between the personal and the professional, between what you work on and what you are.

Well, so what?

so, existence.

December 10, 2013

Evil Editors who Edit

“So did you have to change a lot of things in your book before it got published?”

“Oh yes, loads.”

“Because you’d made spelling mistakes and stuff?”

“Well, sure, but there are more in-depth changes than that.”

“WHAT?! Like what? Character names?”

“Erm, sometimes, but not just. Things like deleting secondary characters, changing the main plot, taking out secondary plotlines, etc.”

“Your editor made you do that?!?”

“Yes. They’re editors so they edit.”

“And you didn’t say anything?”

“I said I agreed with most of the changes, since I did, and disagreed with some, and then we discussed those.”

“So basically, there’s like, lots of things that have changed between the manuscript and the final book.”

“Yes.”

“That’s awful.”

The Evil Editor who Edits is a prominent mythical figure in common representations of bookwriting and publishing. S/he barges in with a red pen and a hatred of everything aesthetic and beautiful and corrupts and destroys the pure virgin innocent manuscript of the poor author.

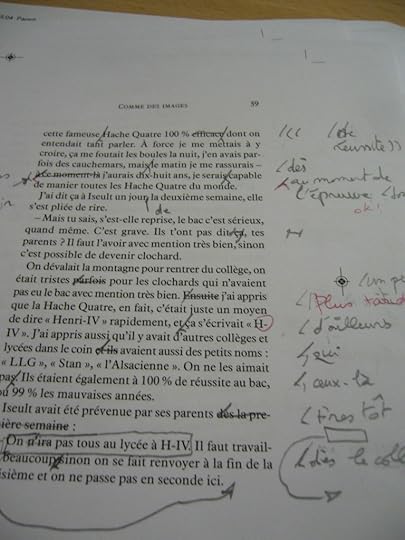

Example of an edited page (version 4 of the manuscript)

There is one central reason for the Evil Editor who Edits to act this way:

MAKE BOOK MORE COMMERCIAL

and absolutely no other reason, certainly not to rectify plotlines that are holey, characters that are hollow, language that is corny, pacing that is wonky and descriptions that are much too long.

There is no way an Editor could possibly do anything like literary appraisal of a manuscript; Editors are cohorts of agents Smith from the Matrix, therefore all they do is make sure that all books published reinforce the general numbness of the docile population. They are controlling and aggressive towards authors because authors are constantly threatening to produce things that will awaken citizens of the world to their situations as Alkaline batteries for gigantic machines.

Your editor edits? You must be weak-willed and lily-livered.

You “shouldn’t be so easily influenced”, “should put up a fight”, and “shouldn’t take any of this”. It’s like you have no self-respect, no respect for your work, and no respect for your readers if you let the Editor do anything to your text.

Your editor edits? Your manuscript must have been awful.

Clearly your book was such a pile of fresh cow dung that it needed to be entirely rewritten by an army of anonymous pen-pushers (god knows why it was taken in the first place, since I’m not Kim Kardashian).

Editors edit; how dare they?

Well that is their job. Editing means modifying a text to make it better, not just Tipp-Exing over typos. Editors are trained readers (see ‘that is their job’); they can spot exactly not just where a text goes wrong but how it could potentially be improved. They will not rewrite but suggest possible ways for the author to rewrite.

Traditionally published authors are not the sole creators of their work (I think self-published authors shouldn’t be either, but that’s another story). The book is the work of a collective and editors have the difficult job of pricing, timing and supervising that collective. Of course they need to ensure the commercial viability of the work, because the book needs to end up in readers’ hands, because the point of a book is to be read. You also need the book to sell or else you won’t eat, remember.

Most of the time, edits are negotiable. If there’s truly a non-negotiable edit and you really, really can’t see why it should be done, your agent will try to intervene. You’re not alone faced with the Evil Editor who dares to edit your work. And you’d be surprised about how little Bowdlerisation actually takes place even in children’s writing. People at Hodder never asked me to modify the vocabulary in the Sesame books, for instance, even though there had been some concern that it was too complex. I couldn’t joke about sex, that’s for sure, but the books talk about money, drugs, poisoning, animal testing, etc.; themes even I thought were probably not going to be accepted. They were.

Inadvertently offensive expressions, however, were rectified.

Yes of course there is censorship in children’s books – god knows we’ve been trying to sell my French books to the UK but they’re too ‘violent and dark’ – but that selection takes place before the book deal, one should hope. Why would an editor take on a book and then ask for all the central sex, drugs and murder plotlines to be removed?

In the best cases, the editor will work tirelessly with you on an extremely ugly first draft and after months (yes, months) of redrafting, two-hour-long phone calls, and dozens of emails, a beautiful swan will emerge from the ugly duckling that Draft 1 was. This is the kind of privileged experience I had with my latest YA in French, Comme des images, which is coming out in February.

First drafts are never publishable as is, and almost never publishable without considerable edits. Yes, even first drafts by established authors. People don’t realise that, because they never see a first draft; all they see is the finished product. Interning in publishing has been such an eye-opener for me: 99% of manuscripts in the ‘slushpile’ truly are terrible; out of the 1% that’s left, almost none of them will actually make it through to publication without several weeks or months of rewrites.

Let me say this again: if you’re still outraged that editors dare to edit, you clearly don’t realise how rubbish most first drafts are.

That’s not to say you can’t either get lucky, or get better at writing first drafts that need less editing. Gargoyles Gone AWOL needed much less editing than Sleuth on Skates, and Scam on the Cam even less than Gargoyles. Does it mean I’m getting ‘better’ at writing Sesame books? Well, in a way – in the sense that I’m getting better at anticipating my editor’s issues with the books. If you know an editor well you can preempt their queries, and immediately delete that secondary character you know they’ll say you don’t need.

There’s only one case so far in my writerly ‘career’ (blah) when I was very lucky and got away with the most minor edits, and that was for my YA novel La pouilleuse, which came out last year. It was almost unchanged by my then-editor Emmanuelle. But when I was chatting to my new editor, Tibo, from the same publishing house, he said to me he would have asked me to rewrite quite a lot of the ending if he’d been my editor on that book.

Would it have been a worse or better book? Neither. Both cases, I think, would have worked perfectly. It would have been a different book; my book and Tibo’s, as opposed to my book and Emmanuelle’s. There’s no book without an editor, and the editor’s vision is an integral part of the book.

(As well as, sometimes, his marginalia:)

Editor getting annoyed at the amount of ‘I said’ in a dialogue (‘J’ai dit! J’ai dit! J’ai dit!’)

Yes, I am eclipsing in this blog post the numerous problems one can still run into with some editors. It’s because this is a blog post In Defense Of. I know that not all editors are sweet unicorn fowls with manes of caramel fudge. And yes, there are some edits on older books I regret doing and certainly wouldn’t do today. But all of the above remarks are valid in the case of a professional, mutually respectful relationship between a reasonable editor and reasonable author who are both hoping to get a good book out of the ‘evil’ edits.

November 26, 2013

Turning the thesis into a book

This is me a little while ago, having just passed my PhD viva:

(The boyfriend would kill me if I put a picture of his face on my blog so I decided to replace it by another face I also like (and which, coincidentally or not, looks pretty much exactly like him (and yes I know, I’m a genius at Photoshop.)))

(The boyfriend would kill me if I put a picture of his face on my blog so I decided to replace it by another face I also like (and which, coincidentally or not, looks pretty much exactly like him (and yes I know, I’m a genius at Photoshop.)))

This is me a few months later with the hard-bound multicoloured thesis:

Look at that self-satisfied little face. Oh if I had known.

At the time, in the words of J.K. Rowling, all was well. I had passed the viva, the thesis was bound and was going to write the Book from the PhD which I already had signed a contract for.

AND A DEADLINE

which at the time sounded very very faraway (this was July 1st; deadline January 31st).

‘OH I’VE GOT AGES!’ she said at the time.

‘I will have all the time in the world to turn the thesis into that perfect thing it was supposed to be!’ she said at the time.

And the PhD viva was mostly about what I should change in order to turn the thesis into a book anyway. So I felt Guided, Secure and Happy.

Please don’t think I procrastinated and didn’t start working on the Book immediately. I barely took two weeks off after my viva and then started working on the Book. But somehow it’s already November The Endth and this is what I’m looking like now:

The book is not going well, people. But this is the opportunity for me to theorise about book-writing from the thesis (hurrah). And this is what, according to my theorisation, I’m doing wrong:

The book is not going well, people. But this is the opportunity for me to theorise about book-writing from the thesis (hurrah). And this is what, according to my theorisation, I’m doing wrong:

I’ve basically decided to rewrite the whole thesis. I’m only going to be reusing something like a quarter of it, and most of it completely transformed. It’s a stupid idea.

I somehow seem to be acting as if this is the only academic book I’ll ever write in my life. I’m therefore cramming every single thought I’ve ever had about children’s literature into it. It’s a stupid idea.

I’m panicking that I’m running out of time, therefore I’m writing faster than I should, therefore it’s not good writing. It’s a stupid idea.

I’ve taken on zillions of hours of teaching and lecturing and marking and doing tons of other things which are preventing me from writing the book. It’s a stupid idea.

I randomly decided to spend two weeks writing an article on something completely unrelated. It’s a stupid idea.

I randomly became interested in a different theory which will not in any way find its way into the book, instead of working on the theories that are important for the book. It’s a stupid idea.

I keep whining about the book. It’s a stupid idea.

Yes, the whole thing is currently driving me insane. Of course there’s a voice in my head (aka that of my ex-supervisor) which helps me a bit:

So yes, I know it’s completely normal. It’s still terrifying. Some days I feel like I’ve said all I’ve got to say, and I still have forty thousand words to write. Some days I feel like I’ll never be able to cram all I’ve got to say in forty thousand words. Some days I want to restructure the whole thing entirely, some days I just think ‘whatever, let’s just take the old structure from the thesis and be done with it’.

So yes, I know it’s completely normal. It’s still terrifying. Some days I feel like I’ve said all I’ve got to say, and I still have forty thousand words to write. Some days I feel like I’ll never be able to cram all I’ve got to say in forty thousand words. Some days I want to restructure the whole thing entirely, some days I just think ‘whatever, let’s just take the old structure from the thesis and be done with it’.

My main problem is that the book presents a theoretical model articulating several different concepts, and I’m finding it really hard to do without a super-long overall introduction. It’s pretty hard, too, to introduce the different parametres of the theory as I go along, because they’re all related to one another. I also feel like I’m being extremely repetitive in my effort to be understood. I also feel like I’m being very descriptive when I talk about the philosophical system I’m using.

And why wasn’t that a problem for the thesis itself? Because a thesis is an academic exercise, where it’s perfectly acceptable to have a very long intro that spells out your theoretical framework, explains what you’re going to do, what your methodology is, etc. And it doesn’t matter if you repeat yourself a bit because it shows that you’re signposting your work. But in real academic books you can’t do that because it’s ferociously boring and not good practice.

When I submitted my thesis I wrote about the pain of realising that it’s never going to be what it should have been (see “How my real thesis was kidnapped by trolls“) (oh God, typing this last sentence I Freudianistically wrote “How my real life was kidnapped by trolls”). I’m having, predictably, the same symptoms now. Even if I hated the thesis in the end, I was still hopeful it would be turned into a Perfect Book. And it’s not going to happen, of course. It will always be a draft in my mind.

For now I’ve made a list of Things to Remember When I’m Having an Acute Book Crisis:

It’s completely normal.

No academic book is a perfect and coherent whole, without repetitions, clear and concise all the way, and revolutionary in both form and content (that’s definitely true).

I’m twenty-four and it’s my first academic book so people will be nice to me (HA. SURE.)

The reviewers will have good advice and recommendations to make it better (if they don’t reject it outright).

There are some good ideas in there.

The publishers won’t let me publish something completely rubbish.

There will be other books, articles, talks and ideas.

The sun will die one day and swallow up the Earth and everything that has ever lived in it, including the ruins of our long-extinct civilisation.

The last of which is the only truly comforting one.

Anyway, I’ll keep you updated on how it’s progressing (or not). In the meantime I need to stop blogging and start drafting again and leave you with this memegenerated kernel of wisdom.

November 19, 2013

How to Write a Picturebook Text in 10 Minutes

Step 1. Wait for the half-baked ideas you’ve been collecting and mulling over to coalesce into a Good Idea for a Picturebook. (estimated frequency: once to twice a year).

Step 2. Develop that Good Idea into a story which would work as a coherent whole formed of interdependent and mutually enhancing words and pictures. Think of the size, shape and orientation of the pages for the story. Think of the style of illustration. (estimated time: 1 week to 1 month).

Step 3. Structure the story into a number of pages divisible by four, making sure that pacing is right, the story arc has the right balance and there aren’t any unnecessary or slow doublespreads. (estimated time: 1 week to 1 month)

Step 4. Now work on the text in your mind, picking the right words to express the right things in relation to the right illustrations you’re also imagining. Juggle with all that in your mind. Pay attention to rhythm, imagery, vocabulary, grammar. Make sure you don’t repeat in the words what is already visible in the pictures. Imagine the pictures at all times. Say the words out loud to make sure they sound good. Think of an adult reading the picturebook to a child. Think of a child reading the picturebook to an adult. Tweak the words in your mind until they’re all necessary and sufficient. Repeat them to yourself until you know the whole text by heart. Read the picturebook to yourself in your mind (close your eyes to see the pictures). (estimated time: 1 week to 6 months)

Step 5. Open a new Word document. (estimated time: 11 seconds)

Step 6. Write down the text of the picturebook, as well as explanations between square brackets of what should be shown by the illustrations. (estimated time: 10 minutes)

You’re welcome.

November 6, 2013

PowerPoint in academic conferences (from abstinence to incontinence)

This isn’t a blog post on ‘how to use PowerPoint’. I’m no PowerPoint expert, and anyway I’m often too lazy to put together properly thought-through PowerPoint presentations for conferences. But I’ve been pondering about the different uses of PowerPoint I’ve witnessed and/or tried, so here are some brief thoughts on their strengths and weaknesses.

1) No PowerPoint

If you’re not over a hundred years old, then not using PowerPoint means either you think you’re God, or you actually are. I’ve listened to exceptional presentations not using PowerPoint. I’ve also listened to atrocious ones. I think it attracts both ends of the spectrum: outstanding people and terrible ones; the brightest and the laziest; the most captivating and the dullest.

Weaknesses:

The correct reaction to a presenter saying, ‘I don’t have a PowerPoint for you today…’

Not having a PowerPoint immediately gets you some negative karma from 90% of the audience.

Such presentations can be a pretext for reading an article tailored for publication rather than a paper tailored for a conference, which is a terrible idea.

Strengths:

If you do it well, it’s extremely impressive.

If you do it well, we’ll all remember your ideas.

People whose non-PowerPointed presentations I like are those who go the extra mile to structure and signpost their talk very carefully, compensating for the lack of visual anchoring. People whose non-PowerPointed presentations I hate are those who take it as a pretext for endless digression. You must be über-rigorous and have some seriously good ideas if you want to convince the audience that they wouldn’t have benefited from any slideshow. (You must also be prepared to see some people closing their eyes or doodling – which probably means they’re much more focused than if you were flashing lots of pretty pictures.)

2) The (almost-)all-pictures PowerPoint

Some people use PowerPoint as visual stimulus, but don’t want to distract from the verbal content of their talk by providing words or sentences on the screen. Their PowerPoint shows a book cover while they discuss the book, or a painting of a reading child while they discuss children’s literature.

While not necessary in any way, those decorative PowerPoints provide staring material.

Weaknesses:

Like number 1, they can be a pretext for people to read off an article to which they’ve added some pictures, rather than a proper conference paper.

Strengths:

With a bit of imagination, it can become extremely interesting.

Yes: it’s wonderful when this type of presentation – with a little help from picturebook theory! – offers the opportunity to have interesting gaps between the verbal and the visual – between the text you read and the pictures you show. This can create surprise and laughter, and tremendously increase audience interest.

A good example is Scott McCloud’s Ted Talk on comics – obviously, as a comic artist and theorist himself, McCloud knows better than anyone how to take advantage of the gap between words and pictures.

The trick to get a laugh is to avoid mentioning the picture. Pretend it doesn’t exist and has a life of its own. In a talk I did a while ago, I was saying that adults don’t read children’s books like children do, and meanwhile the picture on the screen was this one.

The hope is that the part of the audience that’s asleep will be woken up by the part of the audience that sniggers.

The hope is that the part of the audience that’s asleep will be woken up by the part of the audience that sniggers.

3) The ‘hybrid’ PowerPoint: where words and pictures meet

This is the type of PowerPoint I usually do: more pictures than words, but still a healthy dose of verbal signposting – which stage I’m at, which concept I’m discussing. If I read an important quote, I will have it written too so the audience can follow. This type of PowerPoint is pretty good, I think, for people who, like me, have a problem with speaking a bit too fast (that’s an understatement in my case). The PowerPoint ‘underlines’, so to speak, some important concepts and quotations from the presentation.

Weaknesses:

It can feel like it’s just ‘crumbs’ of the presentation, keywords and key pictures but not much around them.

Strengths:

Personally, I feel this is the Goldilocks of PowerPoint: just enough visual stimulation in the form of pictures, just enough handpicked information from the verbal material. It seems to be the type most people go for, too, which creates a feeling of familiarity from the audience.

4) More words than pictures: the verbose PowerPoint

This is the PowerPoint strategy adopted by overcontrolling people who really don’t want their audience to miss anything. This type can go from the relatively word-heavy to the frankly verbose, and it’s generally a lot of quotations, bullet points with the central information of each paragraph, complete references for every sentence cited, etc. Generally the structure of the presentation will also be part of this, so everything is full of Roman and Arabic numerals fighting for every last bit of blank space. It is likely that there will be a slide for acknowledgements listing every funding body, anyone who once approached the presenter while s/he was preparing for the talk, and almost everyone else.

The presenter is generally a former or future schoolteacher, or should be one. S/he is certainly very pedagogical.

Strengths:

The PowerPoint can easily be put online as is, since it will work essentially as a paper in its own right.

You don’t have to listen to the presenter, you can just do what you usually do very well, i.e. read by yourself.

Weaknesses:

See strengths.

As you can tell, I’m not a huge fan of those.

5) The psychedelic PowerPoint of the person who should be working for Pixar.

Also known as the Prezi user, but some PowerPoint presentations I’ve seen have been so full of whirls and twirls and unidentified flying objects that they do just as well. These are the kind of presentations that give you proper vertigo, emit stroboscopic light, trigger three-day migraines if not epileptic fits, and make the scene of the destruction of the Death Star by Luke Skywalker feel a bit slow and lazy in comparison.

Those PowerPoints seem to be implying that a book cover that doesn’t reach its dedicated part on the screen by first dancing the Macarena for ten seconds will not fully imprint itself on the minds of the viewers. They are often full of videos which will rarely play as the presenter intends it, and will require two technicians to be called from the other side of the faculty while everyone in the audience is checking Facebook on Eduroam.

Strengths:

You will amuse and entertain.

It’s a fun reason to procrastinate actually working on the paper.

At least some people will be seeing a presentation like this for the first time.

Weaknesses:

Statistically speaking, I have observed that these are rarely accompanied by good papers, but I’m willing to be challenged on this.

So much distraction that the audience might be more interested in the next somersault of the Papyrus subtitle than by what you have to say.

Here are my thoughts on the matter. Feel free to share your own strategies and preferences.

October 30, 2013

Writing book proposals

In the past few months, I’ve done little else than writing book proposals, i.e. being in the hellish no-man’s-land of half-written books and super-polished synopses.

What are book proposals for?

For books following the First One. Even if your publisher has an ‘option’ on your next book (or series), that next book will likely need to be outlined to them before they give you the money and the deadline.

So, in short, the first book (most often) got bought in glorious, fully-armed completeness, like Athena springing out of Zeus’s skull. However, the second must woo the Editor and the Acquisitions team half-finished, half-naked – stripped down to its synopsis and a few chapters.

Birth of the First Book.

Book proposals are evidently a ‘good’ thing: if you’re at this stage, it means you’ve got a publisher who likes you and wants to see more of your work. But god, are they a pain to write. Book-writing eroticism degree zero, my friend; degree zero.

The first book was similar to your stumbling in your everyday clothes with graceful naturalness into a roomful of people, and one of them falls in love with your little quirks and endearing youness. A book proposal, meanwhile, is like a long-planned date with a man whose head you’d quite like to see on your pillow (with the rest of the body still attached). You’ve spent the past few weeks checking that you’ve got absolutely everything right to achieve the desired outcome. You’re wearing your hair the way he likes it and have revised all the topics he talks about on Twitter, while making sure you retain some of the aforementioned graceful naturalness.

The sexist undertones of the above paragraph are not fortuitous; there is, in book-proposal-writing, something ineffably demeaning and unnatural, something that kills the uncertainty. Like dressing up in a certain way to cajole someone into liking you, it may give you an impression of control, but definitely not one of power.

What should a book or series proposal contain?

Personally, I write a few chapters; how many? As few as will give the Editor a good sense of the tone, characterisation, and appeal of the book. I write a character list, with short descriptions. A general plot summary. A rough evaluation of the genre(s) that the story belongs to, and the age range. And then a very detailed synopsis.

The synopsis isn’t the worst part for me. I always write synopses for books I’m working on – not always chapter-by-chapter, but I don’t mind doing that. I’m a plotter, obsessively structured. But I can guess how horrible those must be for the many writers who are ‘seat-of-the-pantsers’ – i.e., who don’t know where the story is going before they write it. It must be like asking an explorer to chart a territory they haven’t been to yet.

The writing sample is not hugely fun to write. First, there’s this dull feeling that you can’t get too attached to the story because you might never get to write the rest. This is a strange phenomenon, because when you start something which you’re entirely free to finish, you often lose interest in the story and fail to finish it. But it’s all due to your laziness and/or disenchantment with the idea. Whereas the prospect of someone else effectively preventing you from writing the rest makes you extraordinarily keen to finish the book now.

Why am I saying ‘effectively preventing you’? Well, of course, if your Editor rejects your proposal, it can still be offered to other publishers, though that could cause diplomatic drama which your agent might not want to get into. But if they all reject the proposal, then evidently you’ll never write the book, no matter how much you ‘believe in it’. You won’t waste time in finishing a book no one will want.

Secondly, the sample is dull to write because you know exactly what it has to do: give a feel of the whole story, explain who’s who, set the tone, convince the reader that this will be the best story ever, etc.

Once again, that’s something you’d do anyway in the first few chapters – and yet, when you know you have to do it, you suddenly resent the very concept of an exposition scene, and all you want is to begin with a story-within-a-story, a postmodernist mise en abyme, crazy prologues: in short, everything you really shouldn’t do.

Does it sound like I have a problem with authority? Yeah maybe.

Don’t get me wrong, writing book proposals is a very useful skill to master. It teaches you to think more commercially than you would; it turns you into a judge of your own project in its entirety, not just of the emotionally-charged finished story. It also makes the writing process much more secure: once you’ve got the contract, all is well. A deadline and advance are excellent remedies against writer’s block. And you do feel like you are doing something professional, efficient, controlled.

But I have now been working for months on proposals. I have a book proposal that I worked on all August, and I still haven’t shown it to my Editor because my agent (very rightly) wants me to modify it significantly so it’s more likely to be taken on. Then there’s another one I’m working on for yet another project.

The time it takes for rewriting, redrafting, re-synopsising and discussions is enormous, and all that’s before you even have a contract. It also feels artificial: contrary to the first book, when the Editor and agent didn’t know what would happen, and were reading it literally like normal readers, the book proposal gives away the whole plot. This is good, because it allows the Editor to spot potential plot holes before you can dig them, but also bad, because they’ll never have a ‘virgin’ read of the book.

It’s difficult to get excited, I think, about a book you’ve seen in proposal form. Explaining plots (especially the convoluted ones I like) is boring; everything sounds much more complicated in this condensed form than it will be when it’s developed over two hundred pages. And a story is, of course, not reducible to its structure and plot elements.

I don’t have a romantic view of writing, by the way: I’m very much in favour of demystifying book-writing and publishing. This is a job, and book-proposal-writing is part of the job. I don’t have any patience for people who say it’s all about inspiration, emotion and spontaneity; I think we should take time to think about what we’re doing, to structure and nurture our ideas, and to debate them with editors and agents. A book is the work of a collective. Even in self-publishing, there should be no writers who think they can do it all themselves and know better.

But book-proposal-writing, even with the most literary-minded, enthusiastic authors, editors and agents, gives you a weary feeling of über-professionalism; of the perfect polish, watertight smoothness of prophylactics. A prophylactic against crazy deformed, cross-generic, monstrous fiction-babies; as if no mutations could occur once the blueprint has been deemed impeccable.

I’ll be glad, obviously, if and when one of those is finally accepted for sure, and hopefully they will be just as good as if I hadn’t obsessively reworked their first few chapters and synopses before writing the rest. But I won’t forget that their conception involved quite a bit of eugenic tweaking.

Clémentine Beauvais's Blog

- Clémentine Beauvais's profile

- 301 followers