Clémentine Beauvais's Blog, page 5

April 16, 2014

10 Writer Quotes That Really Resonate With Me

I wanted to share with you some quotations about writing that really make my heart beat faster and my eyes fill up with tears because when I read them I think, ‘That’s it! That’s the truth! So I’m not the only one feeling all the pain of this writerly calling that I have, this passion for words that is so full of pain. At long last I feel understood.’

Here they are.

That is so true. Sometimes when no one else will listen (for instance when I’ve been talking about how much I love quotations that are written in wobbly blurry black writing) I bend over my piece of paper and I whisper things into its tiny little ears.

That is so true. Sometimes when no one else will listen (for instance when I’ve been talking about how much I love quotations that are written in wobbly blurry black writing) I bend over my piece of paper and I whisper things into its tiny little ears.

I was saying this the other day to Wilbur (Wilbur is my butler), I was saying Wilbur, you are so lucky to be able to just go on holiday two days a year and forget about all the rest. I just can’t. I can’t. Not. Work. It’s all work work work work and no play ever. It’s hell. And all these thoughts almost always involve thinking of a sepia picture of a typewriter.

I was saying this the other day to Wilbur (Wilbur is my butler), I was saying Wilbur, you are so lucky to be able to just go on holiday two days a year and forget about all the rest. I just can’t. I can’t. Not. Work. It’s all work work work work and no play ever. It’s hell. And all these thoughts almost always involve thinking of a sepia picture of a typewriter.  NO other way to survive. Absolutely NO WAY. Like even if I eat healthy good food all day and take walks and am rich and have no disease, there’s NO WAY NO WAY to survive if I don’t write. I just DIE for goodness’ sake, I DIE every single FLIPPING TIME. I’m so happy someone’s finally voicing this survival impossibility thing.

NO other way to survive. Absolutely NO WAY. Like even if I eat healthy good food all day and take walks and am rich and have no disease, there’s NO WAY NO WAY to survive if I don’t write. I just DIE for goodness’ sake, I DIE every single FLIPPING TIME. I’m so happy someone’s finally voicing this survival impossibility thing.

OH GOD don’t you hate it when you’re writing in your dreams and someone removes the pen you’re holding in reality which is the pen you’re writing with in your dreams? It completely ruins everything you’re writing in your dreams and your dream book doesn’t get written. Then you’re late on your dream deadline and your dream editor gets so furious! I had to pay back a whole dream advance like that last time because the boyfriend had removed my pen from my hand (‘It was going to stain your pyjamas’ SURE). Such a shame you don’t ever get a dream pen and all this dream writing is conditional on your holding a real pen THANK YOU UNCONSCIOUS.

OH GOD don’t you hate it when you’re writing in your dreams and someone removes the pen you’re holding in reality which is the pen you’re writing with in your dreams? It completely ruins everything you’re writing in your dreams and your dream book doesn’t get written. Then you’re late on your dream deadline and your dream editor gets so furious! I had to pay back a whole dream advance like that last time because the boyfriend had removed my pen from my hand (‘It was going to stain your pyjamas’ SURE). Such a shame you don’t ever get a dream pen and all this dream writing is conditional on your holding a real pen THANK YOU UNCONSCIOUS.

I think he doesn’t mean really bleeding, I think it’s a metaphor of some kind, but it’s so true because when you write it hurts so much it really feels exactly like someone’s cut your veins open and all the blood is gushing out. It really hurts physically like that. It does. But it’s nothing at the same time, nothing. We endure it, we have to. Seriously, it’s nothing. Don’t worry. It’s nothing. Ouch… o the pain.

I think he doesn’t mean really bleeding, I think it’s a metaphor of some kind, but it’s so true because when you write it hurts so much it really feels exactly like someone’s cut your veins open and all the blood is gushing out. It really hurts physically like that. It does. But it’s nothing at the same time, nothing. We endure it, we have to. Seriously, it’s nothing. Don’t worry. It’s nothing. Ouch… o the pain.

That really strikes a chord with me. I know people who are not writers and it must be strange not to feel desperate all the time. It’s funny to think that we’re the ones who have this burden, this calling, this thing in us that makes us so desperate… Why us? I hope it stops one day because there’s so much despair, but at the same time I don’t want it to stop because I wouldn’t be a writer anymore… Oh I just don’t know.

That really strikes a chord with me. I know people who are not writers and it must be strange not to feel desperate all the time. It’s funny to think that we’re the ones who have this burden, this calling, this thing in us that makes us so desperate… Why us? I hope it stops one day because there’s so much despair, but at the same time I don’t want it to stop because I wouldn’t be a writer anymore… Oh I just don’t know.

I like the definition of courage that’s implied in there, because some people would say that courage is, like, jumping into a house on fire, or facing up to someone who’s a horrible racist and misogynist, or finally breaking up with a partner who emotionally manipulates you, but no one ever, ever mentions the courage that you need in those moments when you have to write in a way that scares you a little.

I like the definition of courage that’s implied in there, because some people would say that courage is, like, jumping into a house on fire, or facing up to someone who’s a horrible racist and misogynist, or finally breaking up with a partner who emotionally manipulates you, but no one ever, ever mentions the courage that you need in those moments when you have to write in a way that scares you a little.

YESSS!!! I mean, YESSSS!!! The sheer number of people I meet who will just tell you offhandedly, ‘Writers’ idea notebooks aren’t important to them’. It’s extraordinary, it’s like you can’t have a normal conversation with anyone without them bringing up that topic. And the effort it takes to convince them otherwise! Next time I’ll just give them this picture and they’ll understand with the broken glass and fishnet wire that we mean it.

YESSS!!! I mean, YESSSS!!! The sheer number of people I meet who will just tell you offhandedly, ‘Writers’ idea notebooks aren’t important to them’. It’s extraordinary, it’s like you can’t have a normal conversation with anyone without them bringing up that topic. And the effort it takes to convince them otherwise! Next time I’ll just give them this picture and they’ll understand with the broken glass and fishnet wire that we mean it.

I hate those simultaneous yet contradictory delusions. They happen all the time, for instance if I’m tweeting ‘Difficult day with characterisation #amwriting’ and no one retweets or replies, and I think ‘Is that because 1) they don’t care 2) they haven’t seen the tweet 3) they never have this problem with characterisation 4) they’re scared of admitting they have the same problem 5)…’ At least this quote reminds me I’m not alone.

I hate those simultaneous yet contradictory delusions. They happen all the time, for instance if I’m tweeting ‘Difficult day with characterisation #amwriting’ and no one retweets or replies, and I think ‘Is that because 1) they don’t care 2) they haven’t seen the tweet 3) they never have this problem with characterisation 4) they’re scared of admitting they have the same problem 5)…’ At least this quote reminds me I’m not alone.

This one is my top number one favourite of all. I couldn’t agree more. Break-ups, deaths, illnesses, genocides, sun death – there are things out there that sound like they could cause agony of a kind or another. But to me, nothing, nothing can ever be equally agonising as the knowledge that I have a story in me that isn’t told. It’s the Platonic idea of agony; everything else is a replica.

This one is my top number one favourite of all. I couldn’t agree more. Break-ups, deaths, illnesses, genocides, sun death – there are things out there that sound like they could cause agony of a kind or another. But to me, nothing, nothing can ever be equally agonising as the knowledge that I have a story in me that isn’t told. It’s the Platonic idea of agony; everything else is a replica.

I hope you’ve felt inspired too. I’m glad we’re all suffering together, though I still think I suffer a little more.

April 10, 2014

Book Giveaway Results, and other news

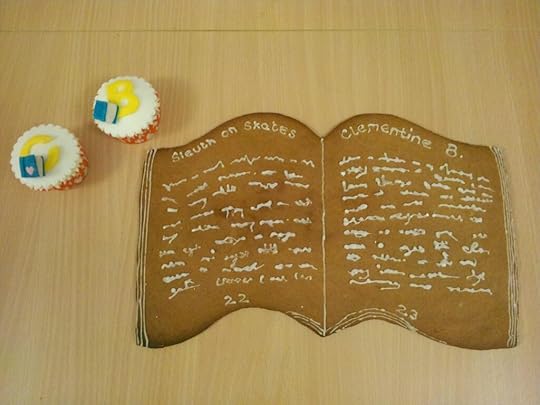

Yes, yes, I know, I’m one day late for the results of the Book Giveaway for Scam on the Cam! sorrysorry. I’ve been really busy with revisions to an article. And the Cambridge Literary Festival, which was this weekend and was aweeeesome. Awesome like this (thank you Sabine and Caitlin for the pictures!):

Learning to draw Claude with Alex T. Smith!

I’ll replace Alex T. Smith one day clearly

And giving a (sold-out!) talk to lots of children and their parents about Sesame! (let me reassure you, the parents were very well-behaved). The children were completely made of amazingness. Quite a few of them had read the first one or two Sesame books and were asking for more, which is probably a good sign. They invented a brilliant Boat Race mystery involving tying an umbrella to a boat to slow it down, and poisoning rowers with potatoes. Maybe they then put it into practice and that’s why Cambridge lost that same afternoon. Hmm…

Pied Piper Sunday

And meeting many other cool authors, including The Dark Lord himself, Jamie Thompson. Here we are posing with our name cakes. I’ve changed, I know. And he looks a lot like me.

Anyway, it was a lot of fun and it was also extremely exhausting.

Anyway, it was a lot of fun and it was also extremely exhausting.

The good news is, too, that Scam on the Cam is beginning to be reviewed here and there and also there and readers generally seem to agree that the book isn’t completely toxic and may help facial gymnastics in the sense of lifting the zygomatic bones (the zygomatic bones are the bits of cheek that go up when you laugh, or something like that, I’m not a doctor, I mean I am, but not one that knows about bodies.)

So you see, happy winner of the BOOK GIVEAWAY whose name I shall give below, you’re a really lucky sort of person today!

Let’s see. I wrote down all the names of the sports-events-crashers:

Then I put them inside the book at a strategic place (if you read it you’ll know why)

Then I put them inside the book at a strategic place (if you read it you’ll know why)

SHAKE SHAKE

SHAKE SHAKE

(dearly hoping only one paper would fall out first)

Well two did.

So I guess I could have been mean and picked one of the two, but you know what? I’m feeling generous today. Irene and Claire, you’ve both won a copy of Scam on the Cam! I hope this fills you with intense joy. Email me your addresses at clementinemel at hotmail dot com and it will be in the post soon!

So I guess I could have been mean and picked one of the two, but you know what? I’m feeling generous today. Irene and Claire, you’ve both won a copy of Scam on the Cam! I hope this fills you with intense joy. Email me your addresses at clementinemel at hotmail dot com and it will be in the post soon!

But for the unlucky of you who didn’t get picked: the great Jim at YA Yeah Yeah is running a giveaway for the THREE Sesame books! All the details are to be found there.

Happy reading everyone!

Clem x

April 3, 2014

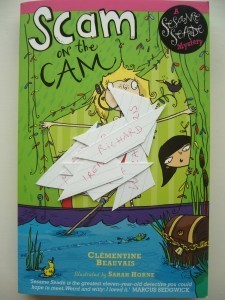

Scam on the Cam: out today!

It’s today!

Welcome to the world, Scam on the Cam!

This weekend is the Boat Race but you don’t need to watch it – because you can curl up in bed with tea and read Scam on the Cam, which features a much more exciting Boat Race. Honestly – even Trenton Oldfield’s Boat Race disturbance is nothing next to Sesame’s.

Do you want a free copy? Take part in the BOOK GIVEAWAY! (at the moment there’s like 3 people. They’re lovely people, sure, but do you want to let them win that easily? No! So add your comment!) The blog post also says everything there needs to be said about Scam on the Cam.

Do you want a print of Sarah’s brilliant illustrations? Head there!

If you want to read about Sarah’s point of view on the books and mine, read the interview posted on the BookBag website yesterday…

…and if you want to know what I would do in a zombie apocalypse, read Tatum Flynn’s brilliant ‘Here Be Dragons’ interview - I was lucky enough to be the first interviewee on her list!

… finally, here are some very recent reviews of the Sesame books: Book 1, Book 2, Book 3…

Additionally, I will be on BBC radio Cambridgeshire this afternoon at 4.05 to talk about the books and the Cambridge Literary Festival.

I think that’s all for now! I hope you all enjoy Scam on the Cam. Just a reminder that the books can be read in any order – but that you can start with Sleuth on Skates if you prefer, of course!

bisous to all!

Clemx

March 26, 2014

Seven Days Till Scam on the Cam!

Scam on the Cam, the third volume in the Sesame Seade series, is coming out in just one week!

Best cover so far? I think so.

I can’t believe it’s already almost the end. I would cry if I were a bit of a crybaby, which I’m not. But also, it’s not really the end – it’s just the apéritif. Because more and more people all over the world are now reading the Sesame books!

And so many kids – so, so, so many kids. It’s brilliant to see that so many of them love the books, and they tell you they do, and when you ask them why they do, they say things like: ‘Because… because… I don’t know’ and when you ask them which bit they prefer they say ‘I like the moment when… well, I like how… oh, I don’t know’. Which is, I’m sure you’ll agree, the best possible review one can get.

“I don’t care about your narcissistic dribble! What’s the book about?”

It all begins when Sesame, Gemma and Toby find an authentic pirate chest on the banks of the river Cam. Could it have anything to do with the fact that a mysterious illness seems to be striking, one after the other, the rowers of the Cambridge University Rowing Team, just a week before the Oxford/ Cambridge Boat Race? (hint: it does).

Sesame is faced with more problems than one, since her precious sidekick Gemma appears to have fallen in love with the deplorable Julius Hawthorne. As for Toby, he’s more interested in collecting frogs. And the pirates always seem to turn up just at the wrong time… Will Sesame solve this tricky mystery? (hint: she will)

Here are some other important facts about Scam on the Cam:

It’s about the Boat Race, but it’s ten times more gripping than the actual Boat Race. No, make that a hundred times. You can read it while other people are watching the race, and laugh and laugh and laugh and say that they’re missing out.

It’s my favourite of the three, and also Sarah’s favourite of the three. And a few bloggers have hinted that it was also their favourite.

Something terrible happens to Sesame’s Phone4Kidz phone.

We meet a real French pirate.

There are many animals, including the usual (cats, ducks, parents), but also new ones (frogs, fishes, rowers).

It’s the last one for now!

Conclusion: this is what you should do now: go into your local bookstore and say “AHEM AHEM! I can see there’s [delete as applicable] only three/ one/ no copies of the Sesame Seade Mysteries in here!” and when the bookseller says, “The sesame seed mysteries? Maybe that’s in the cookery-book department,” you reply “Certainly not! it belongs here. It’s written by Clementine erm… Clementine ermm… Beaver? Beavis? Bovine? Well, something like that. Look it up!”. Then you order quite a few, for your nephew, your goddaughter, your great-aunt and your neighbour, and one for yourself.

And you’ll end up with this rather pretty array of Sesame books

ALTERNATIVELY, you take part in this…

_____________________________________________________________________

BOOK GIVEAWAY!

_____________________________________________________________________

In order to win a copy of Scam on the Cam, leave me a comment on this blog answering this little question:

Which big sport event would you most like to gatecrash spectacularly? and how would you make your big entrance?

Results in 2 weeks’ time!

March 19, 2014

Committed children’s literature (2/2)

The first part of this blog duology (right there) mostly revolved around the publishing and writing of politically committed children’s literature. But what I was most interested in in my thesis were theoretical conclusions to the analysis of such texts. Here are a few of them (necessarily abbreviated and simplified):

What is the implied child reader of committed children’s literature like?

The child reader addressed by politically committed children’s texts (the ‘implied reader’ in Wolfgang Iser’s vocabulary) is primordially someone who would be receptive to the text and its implications – and who would consequently be both willing and able to act to improve the world following his or her reading. This ideal reader would thus be so struck by his/her reading that s/he would attempt to convert these ‘intangible’ encounters with sociopolitical change into ‘real’ actions.

To put it in Sartrian jargon, such texts ‘call’ for a reader who, ideally, would take up the difficult task of accepting responsibility for the world, and contributing to change it. This task is shared between author and reader.

OK, so basically, it’s an implied child reader who would do exactly what the author asks?

Well, actually… no. At least, never straightforwardly, and especially not in the most complex examples of committed children’s literature, where extremely interesting things can happen.

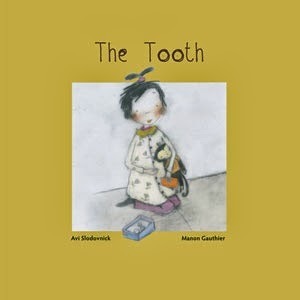

Let’s take for instance the example of The Tooth, a seemingly simple, but actually beautifully profound picturebook by Avi Slodovnick and Manon Gauthier. This is the story of Marissa, a little girl who has to have a tooth extracted. Her mum tells her she can put the tooth under her pillow, and she will get a coin in exchange for it. Instead, though, the little girl decides to give her tooth to a homeless man – quite logically thinking that he needs a coin more than she does. The man smiles, but the narrator closes the story by saying: “Now all he needed was… a pillow.’

The implied child reader in this picturebook is, as said previously, someone who would actualise the values in the text. But it doesn’t mean that the reader is invited to follow Marissa’s actions. In fact, the text is softly but seriously critical of Marissa’s behaviour. By giving her tooth to the homeless man, she didn’t change anything to his material situation. Of course, she’s not a bad person: symbolically, she did good, and the man thanks her with a smile. And she did notice that this man needed money.

The implied child reader in this picturebook is, as said previously, someone who would actualise the values in the text. But it doesn’t mean that the reader is invited to follow Marissa’s actions. In fact, the text is softly but seriously critical of Marissa’s behaviour. By giving her tooth to the homeless man, she didn’t change anything to his material situation. Of course, she’s not a bad person: symbolically, she did good, and the man thanks her with a smile. And she did notice that this man needed money.However, her action is hollow. Marissa is at the centre of a web of adult-woven fictions. She believes that the Tooth Fairy exists and gives money in exchange for teeth. She also tacitly believes that everyone, including homeless people, have pillows. She is wrong, and the picturebook is explicit as to the latter belief at the very least: the last page in the picturebook shows an empty bed – a bed in which the homeless man will not sleep tonight.

The young reader is forced by the iconotext to detach him/herself from Marissa and is thereby confronted to a vertiginous wealth of new questions. If giving her tooth was ‘useless’, what should we do? If it’s not enough to notice that there is poverty in the world, how should we act? The picturebook remains silent as to those matters. The young reader is ‘dropped’ there, exactly at the moment when s/he would need an adult ‘guide’, some kind of prescription, some kind of answer… but there is no answer.

The young reader is forced by the iconotext to detach him/herself from Marissa and is thereby confronted to a vertiginous wealth of new questions. If giving her tooth was ‘useless’, what should we do? If it’s not enough to notice that there is poverty in the world, how should we act? The picturebook remains silent as to those matters. The young reader is ‘dropped’ there, exactly at the moment when s/he would need an adult ‘guide’, some kind of prescription, some kind of answer… but there is no answer.From those silences, the ideal young reader of politically committed children’s literature is asked to become, more fully, an actor of his or her nascent political commitment.

But does the adult know what to do?

In my view, no – the adult doesn’t know. The ‘hidden adult’ * of committed children’s literature is above all an anguished, unsure adult, dispossessed of any means to act. Those texts testify to the adult’s disempowerment.This disempowerment is such that it leads to a subservience to another authority, an authority-in-becoming, that of the child.

But of course, no one likes to feel that one’s authority is being threatened. The ‘hidden adult’ of committed children’s literature is no exception (I hope it’s clear that I’m personifying an entity that isn’t ‘really’ a person here). As a result, those texts are also in places extremely prescriptive and authoritarian.

So we end up with a double discourse of the adult in politically committed children’s literature: on the one hand, a discourse of hope and adult disempowerment, on the other hand, a discourse of authority and prescription. This double discourse, it seems to me, can never be simplified into one or the other, though some books tend towards one rather than the other.

*I don’t have the space here to explain Perry Nodelman’s complex concept of ‘the hidden adult’ in children’s literature. Very briefly: it is the adult authority ‘in’ the text, not necessarily coinciding with any adult character, narrator or author; it is the synthetic figure of adulthood extractible from teh text.

So is committed children’s literature by nature utopian and unrealistic?

Yes, but only more explicitly so than other types of children’s literature. Children’s literature addresses children, and children are, for adults, fundamentally beings-in-becoming and therefore future-bound and hopeful (this is, again, the perspective I adhere to, shared by some children’s literature scholars but not all).

They are therefore fundamentally unpredictable. Since they are unpredictable, they are beings who could still be anything. The adult authority therefore seeks to make them adhere to certain positions, and to let them create their own positions.

However, politically committed children’s literature exacerbates this utopianism which is present in all discourses addressed to children. This is, firstly, because of the themes it frequently tackles: it is a literature which talks a lot about the future, about the impact of human actions, about hope, and about children’s ability to do better than adults. Secondly, it is also due to the fact that such literature often focuses on adult imperfections: the shortcomings of the adult world, of adult sociopolitical systems. As a result, the motif of the child and its logical counterpart – the adult-in-becoming – are glorified.

Such a literature is utopian, unrealistic, or at least idealistic, because it explicly ‘counts on’ the child reader: it depends on the child reader. But, I think, in all discourses addressed to children there is a similar request from the adult – a similar desire, a similar anguish to be listened to.

Any discourse targeting children is always in part an acknowledgement of failure by the adult. This acknowledgement is accompanied by a demand, a prayer. Committed children’s literature is a corpus of texts which makes those acknowledgements, demandes, prayers more visible perhaps than other types of children’s literature.

I’ll stop here!

Clem

March 12, 2014

Committed children’s literature (1/2)

I thought I’d write a little bit about my PhD thesis, which I defended last year, as I’ve never actually said much about it on this blog or elsewhere. So I’m going to write two blog posts on the matter, for those of you dear readers who might be interested in the relatively unfashionable topic of politically committed children’s literature.

In brief: my thesis was principally concerned with children’s literature theory. My starting-point was the currently quite strong theoretical strand of children’s literature which supports the idea that the adult authority, in such texts, is presented as the norm, and/or as more powerful, and the child as other, and/or as less powerful (see list of works at the bottom of this blog post!). My PhD focused on politically committed children’s picturebooks to attempt to nuance this theorisation.

In this first post, a few observations on what politically committed children’s literature looks like today.

Who writes and publishes committed children’s literature these days?

Not a huge amount of people. As I wrote about a couple of weeks ago, France is currently in prey to a pathetic wave of paranoia about committed (feminist/ queer) children’s literature, but in fact most children’s literature internationally remains – in the words of Sartre – ‘embarquée’ rather than ‘engagée’, namely ‘carried along’ passively by its values rather than actively ‘committed’. Children’s literature that explicitly either attacks or defends an ideological position is rare.

Plus, some countries are keener than others to publish and to value politically committed books for children. Some, including France, the US, Scandinavia, and some Central and South American countries seem to have a strong tradition of and love for committed children’s literature. They also have a number of small or independent publishers for whom political commitment is an editorial line and commercial strategy. It’s not currently the case in the UK.

Aren’t politically committed books just politically correct?

No. Of course, ‘political correctness’ doesn’t have a fixed definition, but it is extremely unfair and reductive to claim that politically committed works for children are just saccharine, bohemian-bourgeois texts attempting to show that everyone can be happy together if we would only stop noticing that he’s Black and she’s a lesbian (and all save the Earth by turning off the tap when we brush our teeth).

Many politically committed books say very disturbing things about, precisely, our ability to live together peacefully. They don’t say it’s easy, they sometimes doubt it’s possible. This is the case for The Island, by Armin Greder, for instance – a picturebook in which an immigrant is treated atrociously, and then thrown back into the sea, by an insulat community. Or Le Peintre des drapeaux, by Alice Brière-Haquet (The Flag Painter), which ends with the death of the main character who’d been painting flags for war-torn countries…

Going back to Sartre: such books can truly stage the extreme difficulty of living among others; the fact that we’re thrown against one another, with so little explanation, so few reasons to get on, that we’re always at risk of making terrible decisions.

But yes, of course, there are also many politically committed books that promote tolerance, friendship, diversity, in naïve and utopian ways. Such books are another facet of the same phenomenon: they try to solve the same anguish. But they do so by giving simple answers rather than asking tricky questions.

And there isn’t one ‘good’ category and one ‘bad’ category, but a spectrum of different books which are all (at least, so I theorised) ideologically ambiguous, even the most ‘simplistic’ ones. It’s this ideological ambiguity that intrigued me.

Does political commitment sell books?

Not to a very wide audience. Politically committed children’s books target very specific groups of people and committed publishers have precise strategies as to which customers they should be approaching. They rely a lot on mediators. They lean on communities of committed reviewers, booksellers, parents and teachers, and on blogs and websites rather than the general media.

Nonetheless, they are overrepresented in major book awards, some of which explicitly value books which lead child readers to think about social and political questions.

Is political commitment the sign of a bad book?

‘Quality’ is a hugely tricky topic, but it’s not justified to state categorically that books which have a ‘message’ are by definition bad books. Publishing houses which focus on such works are in fact generally very keen to focus on aesthetic quality of text and pictures, partly because they know that the books will not sell to a wide audience and that, as a result, the books must seduce mediators and win awards.

Yeah right, but the text and pictures might be beautiful, and the book extremely didactic! No?

Yes, of course. And those texts are clearly prescriptive and pedagogical. They attempt not just to entertain, but also to interpelate the young reader as to the state of the world. This pedagogical function is there by definition.

But before shouting that they’re therefore rubbish since art should be for its own sake, it’s good to think about two things:

1) Supporting politically committed literature isn’t a stupid ideological position. It might sound weird, but it bears repeating. It’s a literary and ideological position which has had quite eminent defenders, from Voltaire to Sartre. Many Nobel Prize winners are ferociously politically committed writers. The opposite trend – ‘art for art’s sake’ – appears in favour these days, at least in ‘adult’ literature. But already in 1963, Roland Barthes was lamenting the ‘exhausting’ alternation of ‘political realism and art for art’s sake, between an ethics of commitment and aesthetic purism’. The seemingly ‘natural’ reaction these days (‘books with a “message” are bad’) is reductive. Political commitment in literature is an amply theorised position which can (and indeed should) be analysed coolly and reasonably (of course I’m saying that because… that’s what I tried to do.)

2) Children’s literature is always-already didactic. Not everyone agrees about this, and many people (especially authors) hate being told that, but for many children’s literature scholars and sociologists of childhood, it’s inescapable. Adults and children are not in an equal relationship with one another. The adult’s ‘mission’ is to socialise the child, whether s/he likes it or not. It’s not a ‘problem’, it’s not a ‘scandal’, it’s not necessarily ‘bad’. Children’s literature is by definition a socialising and acculturating literature, a literature that educates into a society and its values.

Politically committed children’s literature is a highly prescriptive type of text which reclaims its socialising ‘mission‘ and puts forwards social, political and cultural values in the hope that they will influence the child reader in his or her future life.

Does that mean that politically committed children’s literature manipulates the child reader?

The words ‘manipulation’, ‘indoctrination’, ‘propaganda’, etc. recur among detractors of committed children’s literature. Again, I think it’s a simplistic reaction. ‘Manipulation’ can occur implicitly or explicitly, actively or passively. Feminist critics of (not-committed) children’s books might reproach them with ‘manipulating’ the child reader into associating the presence of one or the other type of genitalia with specific modes of behaviour or types of personality.

Of course, very many politically committed books for children are equally guilty of presenting particular opinions or values as objective and fixed when they are, in fact, debatable and variable.

I’ll stop now, and next time, I’ll share thoughts that are more related to children’s literature theory and the adult-child relationship.

_____________________________________________________________________

Some key works in the area:

On children’s literature theory and the adult-child imbalance

Gubar, M. (2013). Risky Business: Talking about Children in Children’s Literature Criticism. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 38(4): 450-457.

Lesnik-Oberstein, K. (1994). Children’s Literature: Criticism and the Fictional Child. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lesnik-Oberstein, K. (1998). Childhood and Textuality: Culture, History, Literature. In K. Lesnik-Oberstein (Ed.), Children in Culture: Approaches to Childhood (pp.1-28). London: Macmillan.

Nikolajeva, M. (2009). Theory, post-theory, and aetonormative theory. Neohelicon, 36(1), 13-24.

Nikolajeva, M. (2010). Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers. New York: Routledge.

Nodelman, P. (1992). The Other: Orientalism, Colonialism, and Children’s Literature. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 17(1), 29-35.

Nodelman, P. (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Rose, J. (1984). The Case of Peter Pan: Or the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. London: Macmillan.

On politically committed, or ‘radical’, or ‘subversive’ children’s literature

Abate, M.A. (2010). Raising Your Kids Right: Children’s Literature and American Political Conservatism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Mickenberg, J. (2006). Learning From the Left: Children’s Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mickenberg, J. & Nel, P. (2008). Tales For Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature. New York: New York University Press.

Reynolds, K. (2007). Radical Children’s Literature: Future Visions and Aesthetic Transformations in Juvenile Fiction. London: Macmillan.

March 4, 2014

This week

This week, like many other authors, most of what I’m doing involves talking to people like this:

It’s the week around World Book Day in the UK – and authors are visiting schools everywhere to meet enthusiastic children who want to READ!

It’s the week around World Book Day in the UK – and authors are visiting schools everywhere to meet enthusiastic children who want to READ!

Authors are amazing.

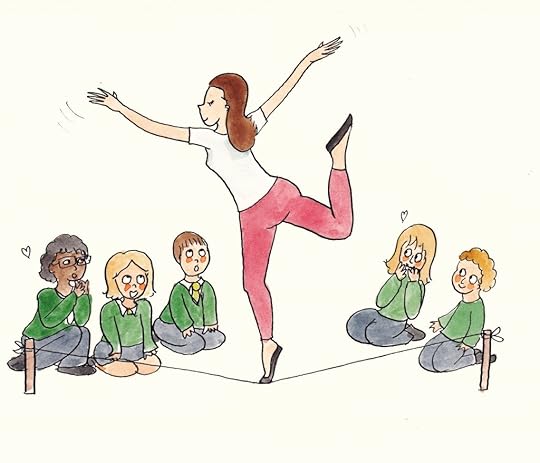

In her school visits, Kate Rundell does tightrope-walking:

Julian Sedgwick does knife-juggling:

Julian Sedgwick does knife-juggling:

But even the rest of us, who just talk, ask questions and show pictures, make children happy:

But even the rest of us, who just talk, ask questions and show pictures, make children happy:

So this is just a little post to say THANK YOU to schools, bookshops and parents for organising all this -

So this is just a little post to say THANK YOU to schools, bookshops and parents for organising all this -

and if you’re wondering what you could do to make your children’s school a little better…

… persuade them to invite an author!

Happy World Book Week to all,

Clem x

February 28, 2014

Books I will never read

Maria challenges me to a blog post on ‘books I will never read’, as suggested by this Guardian article. Hers is there. Here’s mine:

The Fault in our Stars. It started out as a book I just didn’t make time to read, and then slowly evolved into a weird personal challenge to myself that I would simply never read this book, no matter how vociferous the claims that I really should. No particular reasons other than a vague sense of teenage rebelliousness.

The Luminaries. I always try to read all Booker-winners. But ain’t nobody got time for that flipping mahoosive book. UNLESS she wins the Nobel at some point.

Faulkner. Can’t. Sorry. I’ve tried. It’s just – argh!

Hemingway and Steinbeck, been there, NO.

Piers Plowman and The Faerie Queene, but I don’t think anyone’s actually read those. The Pilgrim’s Progress? ha, no.

Anything labelled New Adult. I did try. Most commercial YA (oh God, I’m going to get lynched). Fifty Shades and copycats.

Authors whose books I won’t read because they said idiotic things: Martin Amis, who thinks you have to have a ‘brain injury’ to write for children, and VS Naipaul, who thinks women can’t write. Yeah I know, no author’s perfect. But there you go, I just can’t be bothered with those two bigots.

Like Masha, I’ll probably never read the sequels to:

Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief

The Hunger Games

The Knife of Never Letting Go

Eragon

A Wrinkle in Time

(and many more I’m forgetting)

Some of those I actually enjoyed, but I feel one is enough. Same with The Giver and Holes, which are two of my favourite books in the world, but I somehow don’t want to read the sequels.

Like Masha, I won’t read any more Balzac, George Sand, Dan Brown, and I certainly won’t bother either with any more Sade. Paulo Coelho is also out of the question.

I’m not sure why, but I feel I’m unlikely to ever read Atlas Shrugged, Catch-22, The Leopard, Suite Française, The Road, On the Road.

And I’m not sure I’ll ever manage to finish Ulysses.

February 25, 2014

The quality of silence

School visits in primary school are nothing like school visits in high school. Primary school is Care Bear land: children are enthusiastic, chatty, unhibited, fun, on the edge of their seats. You leave feeling exhausted and deliriously happy, with tripled self-esteem. Especially when they’ve made you a book-shaped cake and cupcakes with your initials.

Yeah I’m showing off.

High school is resolutely different. Something happens in the first few weeks of Year Seven – you can spot it as soon as you come through the door. Pupils look distrustful, sarcastic – they stare at you, and then at one another, exchanging funny little smiles. Some of their questions and comments are unsettling, if not downright offensive. Evidently on purpose. All the more so if you’re young, female and blonde.

But after a few minutes, if you show them that you’re on their side, you gain their trust and the atmosphere gets more relaxes. And then you can talk about really interesting things, and have fun, and tackle serious topics, and let them speak about themselves, and listen to them.

So it’s not the same dynamic at all in a primary school visit and a secondary school visit. In particular, though I often conclude my primary school visits with a reading, it had never come to my mind to do a reading for high school students.

Well, I was having lunch last year during a literary festival in France and talking to another author who suggested I should. He said teenagers loved being read to. I didn’t believe him for a second; I put on my best polite face (“Really? How interesting!”) while secretly thinking “The poor man is completely disconnected from the real world – the teenagers he read his books to must feel terribly offended to be treated like babies.”

Not a teenager.

Coincidentally, though, that very same afternoon I did a school visit in a Year Nine class where the teacher said to me in front of everyone: “The students would very much like you to read an extract from your book to them”. They’d already all read that book (La pouilleuse), or were supposed to (in France, you do school visits only when schools have studied your books).

Since a teacher had asked, I wasn’t going to say no – like most academics, I’ve always scrupulously followed teachers’ orders – but I thought, once again, that the poor adult was completely deluded: teenagers, I firmly believed, don’t like being read to.

Of course I was completely wrong. Hardly had I begun to read that I noticed the extraordinary quality of the silence that had fallen on the room. The students were staring into emptiness, or at their hands or feet. They didn’t look enraptured, hypnotised or stunned – simply silent, and listening.

What struck me was how different that silence was from the silence you get when you read something to primary school children. Primary school children fidget, giggle, whisper. They’re so used to being read to, it’s just normal to them.

Not to those teenagers. They’d lost the habit – the habit of finding themselves in a situation where there’s nothing else to do than to listen to a word after another, to each sentence with its rhythm and musicality. For them, I could tell, it felt new.

(And no, I’m not subtly bragging about the rhythm and musicality of my book; I’m pretty sure I could have read them anything. It was all about the situation, not the text.)

(And no, I don’t have his voice.)

When I finally found a place to stop, there were a few more seconds of that silence. Then they started moving again, and some of them said, “Just a few more pages…”

Since then, I always try to take time at the end of my high school visits to read extracts from the book. Something always happens. I know, now, that literature teachers know it – and sometimes take advantage of this amazing quality of their listening, to read them texts that they wouldn’t read themselves with the same focus, the same attention.

At the risk, of course, of gradually breaking the spell…

February 12, 2014

Children’s literature and the current political situation in France

Dear UK/US readers, you might have heard of the Hollande/Gayet affair, but that’s so yesterday now. Something much more scandalous has taken its place in the French media: a children’s book.

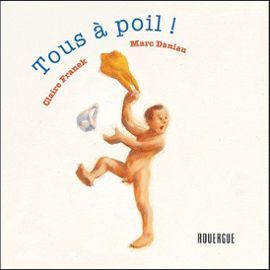

On Sunday, Jean-François Copé, head of the socially-conservative, neo-liberal party (Sarkozy’s party, right of centre) discovered children’s literature. It was a bit of a shock: the poor man’s blood ‘curdled’ (his own terms) when he laid eyes on this picturebook:

Tous à poil (“All naked”), by Claire Franek and Marc Daniau, had since 2011 lived a quiet, fairly unnoticed life on libraries’ bookshelves. Its only claim to fame was that it had been, like 499 other books (including one of mine), included in the list of ‘recommended reading’ for schools by the Ministry of Education.

Tous à poil (“All naked”), by Claire Franek and Marc Daniau, had since 2011 lived a quiet, fairly unnoticed life on libraries’ bookshelves. Its only claim to fame was that it had been, like 499 other books (including one of mine), included in the list of ‘recommended reading’ for schools by the Ministry of Education.

This fun little picturebook shows dozens of people stripping: Dad, Mum, children, the neighbours, the schoolteacher, the President – and going to the beach. The avowed aim of the author, not that it matters much, was to trigger smiles in the child reader and de-dramatise body image.

Jean-François Copé, however, was not amused. He brandished the odious picturebook during an interview on TV and proceeded to read it out loud, making sarcastic comments and noting that ‘at some point, in France, we’re going to have to stop to think about what we’re doing to our children.’

Jean-François Copé overestimating the size of his own brain

By Monday morning everyone on French news was talking about this book, and about children’s literature in general, and children’s editors and authors were being interviewed. It had been a while since children’s literature had been on the news so much, and it was actually funny, so we all thanked Copé for the sudden rise in interest for our work.

By Monday afternoon we’d all stopped laughing. Because no sooner had Copé finished his diatribe that a quagmire of Catholic, right-wing extremist ‘associations’ and groups declared war on politically committed children’s literature, stating that their next plan was to ban from school libraries offensive books such as Tous à poil.

Their target, in fact, is perhaps more accurately all those books that promote gender equality, or hint at the fluidity of gender performativity. And of course, books that feature same-sex relationships. For the first time in France, which is by no means a prudish country for children’s literature, we see emerging a very strong desire to prevent librarians, teachers and booksellers from stocking and recommending children’s books that present ‘alternative’, radical, or even slightly transgressive ways of life.

And it wasn’t the first time – things like that have been happening increasingly often for the past couple of years.

Last week, there’d been a much smaller, but (to us children’s literature people) just as noticeable furore on the Internet about a children’s novel called Je porte la culotte/ La journée du slip. Recently published (also by Le Rouergue), that novel contains two stories; one in which a little boy wakes up as a girl, and the other one in which a little girl wakes up as a boy.

A children’s literature blog reviewed it, and the review caught the eye of extremist groups. The authors received death threats. Reading the comments on the original blog post is enough to make you want to stop writing politically committed children’s books forever.

You might be wondering where all that is coming from – France, after all, has a long tradition of subversive and politically radical children’s literature. Yes, but conservative politicians and traditionalist Catholic activists are only just beginning to discover them. Or at least, they’re only just beginning to make their opinions heard about them, because the media are now listening to these small clusters of people who are becoming more and more organised.

It had been brewing for a while but truly took shape last year, when François Hollande’s law legalising same-sex marriage, which we supposed would be just a formality, woke up a normally silent and disorganised fringe. Astonished, we watched people demonstrate, sometimes violently, against that most banal of requests – allowing same-sex couples to marry.

The movement didn’t stop with the gay marriage laws being passed. More recently, galvanised by Spain’s proposed restrictions on abortion, the same activist groups took to the streets again to protest against abortion in France.

Now they’ve found yet another thing to protest against. The Minister of Education as well as the Minister for Women’s Rights in the Hollande government are currently encouraging schools to teach children about the non-essentialism of gender (you know, that idea that was more or less radical in the fifties). Children are asked in schools to engage with the stupendously controversial idea that not all nurses need to be female nor all air pilots male.

Activists are calling this the rise of ‘gender theory in schools’, which refers to absolutely nothing else than the strawman they created by naming it so. Spectacularly, two weeks ago, one of their ‘leaders’ sent hundreds of texts to parents of young children, urging them not to put the little ones at school that day: they were going to be ‘taught to masturbate’, there would be ‘a sexologist coming to school’, and, wait for it, ‘Jewish doctors would come and examine their willies, telling them that they can change them for vaginas if they don’t like them.’

I know.

Jean-François Copé’s absurd attack on Tous à poil thus takes place at a hugely heated time in France, and here we go, he’s given those people another thing to focus on: they’ve already declared that their next battle will be children’s literature.

What power do these people truly have? It’s difficult to say. They’ve dominated our news for over a year. They’ve resorted to acts of violence. And this is all happening some twelve years after the extremist right wing party, Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen’s Front National, reached the second round of the national elections for the French Presidency.

So we children’s writers and illustrators might be posting funny pictures of naked children in children’s books on our Facebook profiles, and Photoshopped pictures of naked Jean-François Copé, and showing support for our colleagues who inadvertently launched a media storm, but we’re not as merry as we may look. It’s ridiculous, yes, but a dangerous kind of ridiculous.

We’d really prefer children’s literature to make headlines for a different reason. In the meantime, we’ll retreat back to our quiet little Internet niche of friendly forums, blogs and Facebook pages. And write yet more politically committed books, because clearly they’re increasingly needed.

Clémentine Beauvais's Blog

- Clémentine Beauvais's profile

- 301 followers