Barbara Rogan's Blog, page 9

September 29, 2012

A Former Slave Writes to his Old Master

I came across this wonderful, authentic letter from a former slave named Jourdan Anderson to his old master, Col. Anderson of Tennessee. After the civil war, Jourdan moved to Ohio with his wife, also a former slave, and found work there. The Colonel wrote to his former property, inviting him to come back to work on the plantation, this time as a free man. Below is Jourdan Anderson’s perfect reply. Keep reading till the end—it gets better and better.

This letter comes from the Project Gutenberg eBook. I found it on the Letters of Note website, which will include it in an upcoming book of notable letters. That site’s log line is “Correspondence Worth of a Wider Audience.” I think this letter is worthy of the widest possible audience, and I hope you’ll pass it on.

LETTER FROM A FREEDMAN TO HIS OLD MASTER.

[Written just as he dictated it.]

Dayton, Ohio, August 7, 1865.

To my old Master, Colonel P. H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee.

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the[266] folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq.,[267] Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.

September 24, 2012

Top Ten Ways To Get Rejected By Your Dream Agent

Last week, West Coast literary agent Pam van Hylckama Vlieg was in her car on the way to pick up her daughter at school when she was suddenly attacked by a man wielding a baseball bat. He started banging her head against the steering wheel and ran off only when her dog bit him in the arm. This was no carjacking or random attack. Just hours after the attack, police arrested a man who had written a threatening letter after his work was rejected by the agent.

Before we go any further, let’s take a moment to say hats off to the dog, a Jack Russell terrier, I believe. Dogs should be standard issue for literary agents.

I was doubly shocked by this attack. First because I felt for and identified with the agent. I don’t know Pam, but I was a literary agent myself for many years and, like most agents, encountered the occasional unhinged writer. I was also shocked, with true writerly egotism, because the story so closely mirrored the plot of my upcoming novel, A Dangerous Fiction. In my version, a New York agent is stalked by a writer furious at being rejected, whose behavior escalates from harassment to sabotage to violence. The police were not as quick in my story to discover the culprit as they were in real life; but as often happens with fiction, my villain was smarter. The real–life attacker left his name and address in the agent’s files.

The day after the real attack, my e-mail box was full of messages from people who had read proofs of my book – – several fellow writers and people from Viking, my publisher – – exclaiming about the coincidence. The coincidence was indeed surprising, the attack wasn’t. Writers take rejection very personally, they get a lot of it, and it has a cumulative effect. Since agents are regarded as gatekeepers to the promised land of publication, they often bear the brunt of writers’ frustration. Their role is not unlike that of unfortunate Walmart employees tasked with keeping order outside the store on the morning of Black Friday. Not for nothing do agents barricade themselves behind assistants, answering machines, and form letters. Rejection is never fun for anyone, and a little distance can make it easier to bear. But for someone who’s unstable, that distance in itself can be a provocation.

I hope I don’t need to tell anyone reading this post that pounding the head of a potential agent into a steering wheel is not the best way to gain representation. It is in fact so counterproductive that one has to wonder whether the attacker actually hoped to succeed. Most writers, when they set out to gain representation, really do want someone to sell their book. There’s plenty of good advice available for these writers, including these articles and resources. But there must also be some writers who fear success and are determined to sabotage it. Perhaps being rejected plays into their self-image as misunderstood geniuses. So for those who are determined to fail, here is a list of the top 10 ways to get rejected by your dream agent:

1. Be crazy. If you harbor conspiracy theories, make sure to share them in your query letter. If you have the solution to the world’s problems, let the agent know. If your novel was dictated by any alien, occult or deceased beings, this is vital information for your literary representative.

2. Be creative. There are plenty of ways of skinning a cat. If an agent won’t take your phone calls, find out where she lives and drop by. Send her gifts. Let her know she’s special.

3. Get cozy. Call the agent by her first name. Let her know you’ve done your research, not only into what genres and authors she represents, but also where her kids go to school, her mother’s nursing home, and her Social Security number. This will impress her with your research skills. Don’t hesitate to share your own personal story with her, as well. If you’ve been unjustly incarcerated or hospitalized, discuss it in the query letter and let her know you’re fine now.

4. Pattern Your Book on Current Bestseller. Why argue with success? Originality is for losers; you’ve worked out a formula that guarantees you a spot on the bestseller list.

5. Send your first draft, hot from the word processor. Don’t sweat the small stuff, or the big stuff, either. Editors exist to clean up in the wake of geniuses. Let them earn their keep.

6. Rules are for suckers. Real writers are nonconformists. Check out the agent’s rules for submission, by all means, but do your own thing. If he asks for a query of one page, write six if you need them. If he asks for a chapter, send the whole manuscript. You know he won’t be able to stop reading once he’s begun. You’re just saving a step.

7. Explain how much money your book will make them. Agents are idiots and don’t know what sells. Show them they’re dealing with a savvy customer.

8. Carpet bomb the industry with generic query letters. Just because an agent asks for scholarly nonfiction is no reason not to give him a chance at your paranormal thriller. Plus, agents are idiots. They’ll never know.

9. Promote yourself. Query letters are sales pitches, after all. Tell them you’re the hottest thing since sliced bread and John Grisham. Compare your work to the top-selling books out there and explain why yours will leave them in the dust.

10. Insult the agent. They’re sick of toadies. Some clever sarcasm and home truths will win you their respect.

The good news for those seeking rejection is that the odds are in your favor. Incorporate a few of these methods into your pitch and success is guaranteed.

A DANGEROUS FICTION will be published by Viking/Penguin in July, 2013. In the meantime, Barbara’s last three novels have just been reissued in e-book and paperback form: SUSPICION, ROWING IN EDEN, and HINDSIGHT.

September 15, 2012

The Third Way

It’s always nice for a writing teacher when her students go forth and publish. Tiffany Allee didn’t even wait for class to end. She was in the middle of one of my Next Level courses when she got her first offer of publication. The fact that she sold her work did not come as a surprise (I’d read it), but the speed of her success was startling. One year later, she has three novellas in print and, I believe, a full-length novel in the works.

In this blog, we had several interesting discussions about the merits of trade publishing versus self-publishing. But there is a third way, one that takes advantage of the digital revolution but doesn’t place the whole burden of publishing on the writer, and that’s the way Tiffany Allee chose. I’ll let her tell you about it in today’s guest blog.

From the desk of Tiffany Allee:

During the last few years, writers have argued the merits of commercial versus self-publishing. There are strong lines of division, with (I think) most writers seeing the potential good aspects of both methods.

My road to publication has been a little different. I’m not published with a big New York publisher, although that is definitely something I will be pursuing in the future. But I’m also not self-published. I’ve gone another route, which is to publish with smaller publishers that concentrate on the digital market.

Keep in mind while reading this post that my experience is just that, my experience.

The Beginning

The first writing project I finished (beyond a short story here and there in college classes) was a novel I wrote mainly during NaNoWriMo in 2010. It wasn’t the best novel in the world, but it gave me confidence that I could finish a novel—a first draft of one, anyway. It had a beginning, a middle, and an end. And it all sort of worked together into a fairly cohesive story.

But I knew that before I could fix that story—never mind writing something better—that I really needed to concentrate on important craft skills. Doing that while working on a 90k word novel was daunting. So I decided to write shorter—novellas.

The Problem

Novellas proved to be a wonderful way to learn (and they’re quite addictive). I was able to pick up critique partners to help me even more. I also took a fabulous online workshop with our host here today, Barbara Rogan, that really helped me to build a revision process.

But then, when I had a couple of shiny novellas on my hands, I wasn’t sure what to do with them. Novellas don’t generally sell to traditional publishers, and I wasn’t confident enough in my abilities to self-publish. I needed someone in a professional capacity to agree with me that the works were good enough before I would be willing to put them out there.

After researching digital-focused publishers, and submitting to a few of them, I found homes for my novellas.

But…Do They Edit?

Something I’ve seen touted out there in reference to publishers, especially digital ones, is that they don’t edit. Well, I can say that’s not the experience that I’ve had with any of my publishers.

While the process varies from publisher to publisher, I can speak to what I have seen. I’ve published most of my work through Entangled Publishing, so I’ll focus on my experience with their process here. It is quite similar to what I’ve heard about and seen elsewhere.

Entangled uses what I’ve heard referred to as a three-step editing process, meaning that a book goes through at least three rounds of edits prior to copyediting. Each of these rounds may actually involve more than one exchange of the MS between editor and author, particularly the first round.

Starting with an edit letter detailing content or big picture edits, and ending with line edits, the editing process can be very involved. While an author can push back on some of these suggestions (and I have, on a couple of things here and there), these changes are what bring the story to the next level.

Whew.

And it’s still not done. Then the story goes to the copyeditor. Again back to the author for change approval. Then galleys come out and the author and editor both comb through the story to make sure nothing has slipped through the cracks.

Now that’s a process that would be very difficult to replicate for a self-publishing author. And I suspect that it’s on a level similar to the bigger publishers out there. I don’t know that all digital or small publishers processes are quite so thorough, but that’s one reason why researching the right place to submit to is so important.

At every step in the process, I have never been short of stunned at the level of professionalism I have seen, and the sheer editorial talent that my stories have benefited from.

The Good Stuff

There are definite advantages of going through a smaller publisher, especially one with a digital focus.

Length: Although accepted lengths vary by publisher, they are almost always more lenient than your average NYC house. I’ve seen acceptable ranges from 5k to 120k, and everything in between.

Royalty Rates: Royalty rates with digital publishers tend to be much higher than at NYC publishers, particularly for ebooks.

Timelines: It is feasible for an author to see his or her book published within a year of submission. This isn’t usually possible in the agent to big house route. I will say that wait times on submissions aren’t fast by the definition I would have had prior to learning about the publishing industry, but waiting only a few months on a submission is quick in this world.

Editing, Cover Art, and Marketing: I’m listing these as an advantage, not over a NYC house, but over attempting to self-publish. Cover art is expensive. Good editors are expensive. Marketing is…you guessed it, expensive. And cutting corners in any of these areas is a good way to make sure no one ever hears about your book, let alone reads it.

Promotion: The type of promotion you get varies by publisher, but most excel at guiding their authors on what to do themselves to promote (and it’s a far more complex process than one might think). I have been lucky with Entangled because they provide me with a publicist who helps get my name out there, and who schedules blog tours and promotions for me. I can’t tell you what a timesaver that is.

The Not-So Good Stuff

Advances: Few digital houses offer advances. Most who do offer advances that just aren’t comparable to big houses.

Cover Art and Marketing: Larger commercial publishers may have larger budgets for marketing and cover art.

Distribution: Larger publishers also have distribution networks that not all smaller or digital publishers can compete with. And the importance of shelving books where readers can see them cannot be minimized. It’s huge. (I should also add that some of the larger digital publishers do have excellent distribution in place, and their print lines can be found in bookstores.)

Self-publishing: Pubbing yourself will still offer higher royalties, faster timelines, and even more flexibility with length and genre than a digital publisher. Of course, this comes with a lot of additional cost and risk.

Things to Keep in Mind

Research is your best friend when looking at any publisher or agent. Check online at reputable sites. My favorite site to start researching is the Absolute Write forum. Keep in mind what is important to you in a publisher, and what your expectations are. Talk to other writers. Look at things like sales, publisher reputation, and the backgrounds of the individuals behind the publishing company.

For example, if you want to see your book actually shelved at the Barnes & Noble by your house, you’ll probably want to look at the traditional agent to big publisher route, or to the print lines at Samhain, Entangled, or other smaller publishers whose distribution might make that possible.

While smaller and digital publishers may have higher acceptance rates than some bigger houses, they’re still not easy to break into. Most of the more established ones who sell well have acceptance rates well below five percent. So you still have to make sure to put your best foot forward when querying.

Some genres sell better through digital publishing. There is no question that romance and erotica sell better than other genres, likely in part because some of the pioneers of the digital industry were romance and erotica publishers. But other genres are becoming more common. Publishers like Carina put out all sorts of genres and do not require romantic elements in what they publish. Samhain now has a horror line. Digital publishers of non-romance genres may be more difficult to find, but they are out there.

In Closing…

Digital titles are becoming very popular. My own publisher has had wonderful success, as have others, with multiple titles hitting the New York Times and USA Today lists.

I can say that I am extremely happy. Not only have I learned so much more than I can communicate via a single blog post from my editors and my publicists, but I feel like my stories have only benefited from the brilliant people who I have worked with along the way.

Thanks, Tiffany! I think it’s important to remember that the Big Six are not the only game in town, nor is self-publishing the only alternative. Writers have more choices today than ever before.

Tiffany’s books are very fun reads in the paranormal genre, original and well-written. I hope you’ll give them a read.

September 12, 2012

Films About Writers: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly

Sorry to be late with this post. I spent the last few days recuperating from a movie I saw over the weekend. The Words is about a writer who plagiarizes the work of another writer, gains fame and fortune, and is then confronted by the real author. It should have been a good story, if not a particularly cinematic one. Instead, it was a particularly egregious offender in a long line of terrible movies about writers.

Part of the problem is surely that it is so difficult to make anything dramatic of the writer’s process. If you were to set up a WebCam in front of my computer, here’s what you would see: Writer stares at screen for 20 min.; writer types a sentence; writer stares at screen. Repeat. Not exactly the stuff of scintillating cinema. Moviemakers, and readers in general, tend to mistake the product for the process. The most exciting book in the world is written in the same sedentary fashion as the most tedious.

Naturally, filmmakers need to spice it up. Teeth are gnashed, hair is ripped out at the roots, grooves are worn in old wooden floors. Shakespeare In Love was one of those: an otherwise estimable film that couldn’t resist tarting up the writing process with histrionics, as if the plays were written not in ink but in blood. The Words featured an early montage of such melodramatic agonies of creation. I smirked, but with a sinking sensation. Next came the scene in which a publisher summons the writer, praises his book to the skies, and then declines to publish it. I nearly choked on my popcorn. As if! Filmmakers go to immense pains to make every detail of their police and CIA procedurals as realistic as possible. Why, then, is it okay to write such a ludicrous scenes about the writer’s life? No publisher ever calls a writer in to reject his work in person. It is done through intermediaries: his agent, if he has one, or an e-mail, or simply through no reply. When I saw that scene, I knew I was in trouble. The film also had difficulty differentiating between the roles of publishers and literary agents, very basic stuff. And when it quoted from the miraculous purloined book in question, the prose was so flat and boring (think Hemingwayesque, if Hemingway had had a tin ear instead of perfect pitch) that the whole premise of the story was undermined.

According to the movies, lots of writers are psychotic. It seems to be a professional hazard. See Meryl Streep as the romance novelist from hell in She Devil. Johnny Depp develops a split personality in Secret Window, while in As Good As It Gets, Jack Nicholson suffers from multiple psychological problems. Writers are always being pursued by characters from their own books (especially if the book in question was written by Stephen King) or vengeful fans (ditto). You’d never see writers in films as they are in real life: working stiffs with kids in school and mortgages to pay.

According to the movies, lots of writers are psychotic. It seems to be a professional hazard. See Meryl Streep as the romance novelist from hell in She Devil. Johnny Depp develops a split personality in Secret Window, while in As Good As It Gets, Jack Nicholson suffers from multiple psychological problems. Writers are always being pursued by characters from their own books (especially if the book in question was written by Stephen King) or vengeful fans (ditto). You’d never see writers in films as they are in real life: working stiffs with kids in school and mortgages to pay.

Still, every once in a while, a film gets it gloriously right. I loved Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, the story of Dorothy Parker, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, and the Algonquin Round Table: the writers’ Camelot brought to life. Capote was a brilliant movie about a writer who falls in love with his subject but sacrifices him for a better ending to his book. I felt it says something true about writers. And who could forget the Coen brothers’ hallucinatory Barton Fink? John Goodman as Satan is perfect, and so is John Turturro as the aspiring screenwriter who vacillates in a very writerly way between hubris and terror.

brought to life. Capote was a brilliant movie about a writer who falls in love with his subject but sacrifices him for a better ending to his book. I felt it says something true about writers. And who could forget the Coen brothers’ hallucinatory Barton Fink? John Goodman as Satan is perfect, and so is John Turturro as the aspiring screenwriter who vacillates in a very writerly way between hubris and terror.

How about you? What are the best and worst movies you’ve seen about writers?

September 2, 2012

The Best Part of Publishing

The problem with living in the golden age of anything is that you never know it at the time. It is what it is, that’s all. Only much later, when it’s over, do you realize in retrospect what an extraordinary period it was.

I thought about this the other day when I came across a piece in the New Yorker, “Editors and Publisher” by John McPhee: an affectionate appreciation of his two great New Yorker editors, William Shawn and Bob Gottlieb, and his publisher, Roger Straus Jr. It occurred to me that I had known and worked with two of these men, Bob Gottlieb when he was editor-in-chief of Knopf, and Roger Straus Jr. during his long tenure at the helm Farrar, Straus and Giroux. I was, at the time, a young literary agent based in Tel Aviv, representing Israeli writers abroad and American and European writers in Israel. I had moved from New York to Tel Aviv at the age of 22, worked for an Israeli publisher for a year, saw a niche into which I might fit, and at the ripe old age of 23 launched the Barbara Rogan Literary Agency.

The need was there, and within a year or two I was selling rights for publishers like Random House, Morrow, Knopf, Doubleday, Bantam, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which is how I met Bob Gottlieb and Roger Straus Jr. To them, I must have looked like a kid who ought to be working in the mailroom. But they treated me with the utmost respect and collegiality, considered my submissions seriously, and talked up the books on their current lists. Knopf shared quarters with Random House and its sister imprints in a handsome, modern building on Third Avenue in midtown, and I would spend whole days meeting various people in those offices. At some point I would be ushered in to Mr. Gottlieb’s office. He was an august presence to me, head of one of the best imprints in the US, and editor of a long list of writers I greatly revered, including John LeCarre, John Cheever, V. S. Naipaul, and Edna O’Brien. He never took me to lunch – he saw publishing lunches as a complete waste of time, and usually ate in his office – but he was unfailingly gracious and would spend an unhurried hour or so talking about books and publishing with a young agent. He never bought any of my Israeli writers, but I sold a great many of his in Israel, in part because they tended to be very good writers, but also because he spoke of them so compellingly that I was infused with a missionary-like zeal to go forth and find them a home in the Promised Land.

I had something closer to a friendship with Roger Straus Jr., one of publishing’s great characters. I saw him every time I came to New York, and once a year at Frankfurt. He was wonderful to look at, still handsome in his 60s, with a great mane of white hair swept back from his aristocratic forehead; but he was even better to listen to. When he talked about the latest book that had captured him, it was with the passionate enthusiasm of a boy, informed by decades of reading and publishing the best of world literature. I particularly remember him proselytizing about Nobel prize winner Elias Canetti, whose Crowds and Power Roger had published: one of the most important books ever written, he told me, which for once was not the usual publishing hype.

I had something closer to a friendship with Roger Straus Jr., one of publishing’s great characters. I saw him every time I came to New York, and once a year at Frankfurt. He was wonderful to look at, still handsome in his 60s, with a great mane of white hair swept back from his aristocratic forehead; but he was even better to listen to. When he talked about the latest book that had captured him, it was with the passionate enthusiasm of a boy, informed by decades of reading and publishing the best of world literature. I particularly remember him proselytizing about Nobel prize winner Elias Canetti, whose Crowds and Power Roger had published: one of the most important books ever written, he told me, which for once was not the usual publishing hype.

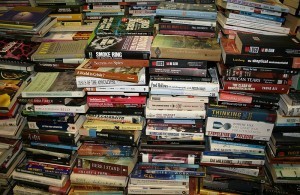

His language was famously profane. “Fucking” was his favorite adjective, which amused me no end. I wasn’t offended; this was the vernacular of my 20-something contemporaries, but it seemed wonderfully Bohemian coming from a man my grandfather’s age. His accent was unusual and reminded me of screwball comedies starring Cary Grant and Lauren Bacall. “Darling” he called everyone, but he pronounced it dahling; every new book on his list was mahvelous. As McPhee wrote, “his words wore spats.” It wasn’t an affectation; he’d been raised that way. His mother was a Guggenheim; his father’s family owned Macy’s. Playing superego to Roger’s id was his longtime assistant, the always elegant, always kind Peggy Miller. I loved going to their offices on Union Square, a warren-like space they’d outgrown long ago, crowded and dusty, with stacks of books everywhere. Random House’s offices were elegant, and I was always on my best behavior there, but visiting FSG felt like going home.

Roger was particularly loyal to his writers, whose backlists he kept in print regardless of economics. He liked to say he published writers, not books, and he must’ve said it often, because I remember hearing it, and so, in his memoir, does John McPhee. Roger meant it by way of contrast to his corporate competitors, bean-counters, he called them, and ruder names. He sought out great literature to translate, befriended the great publishers of Europe, and saw himself, I believe, as a leading citizen of the wider world of ideas. Certainly I saw him that way.

I was also a great admirer of Barney Rosset, head of Grove Press and the American publisher of T. H. Lawrence, Samuel Beckett and Henry Miller. The first time we met was for lunch, not in one of the usual upscale publishing hangouts, but in a funky, blue-collar eatery near his office. Knowing of his epic court battles against censorship, which in the case of Henry Miller went all the way to the Supreme Court, I expected a fire-breathing dragon of a man; but Barney was a warm, bookish man with no interest in rehashing old battles. We started out talking enthusiastically about the Israeli writer whose rights he’d just acquired from me, and ended up commiserating with each other on the scarcity of translated fiction in the US and the provincialism of American publishing compared to European and Israeli.

Today there is, to put it delicately, a different publishing climate. Back when I was an agent, some important publishers, including FSG and Grove, were privately owned, and even those with corporate owners operated more or less autonomously. Now, after a generation of mergers, buyouts, and consolidations, we have the Big Six. I was representing Bantam in the ’70′s when a marketing man was elevated to the post of publisher, instead of someone from the editorial side. The publishing world was shocked. “It’s the beginning of the end,” editors whispered. “It’s the writing on the wall,” others said. That sort of dichotomy hardly exists anymore, and to the extent that it does, the balance of power has shifted completely. In the past, publishers and editors like Roger Straus, Barney Rosset, and Bob Gottlieb decided what they wanted to publish and tasked their marketing departments with selling those books. Now, acquisitions are made by publishing boards that look hard at every prospect’s commercial viability. There is less scope, it seems, for individuality and eccentricity, less loyalty to one’s writers, less time allowed for writers to find themselves and their markets.

And yet some things haven’t changed. I realized this over lunch some weeks ago with Tara Singh, my editor at Viking Penguin, who’s not much older than I was when I started my agency. She told me that what she loves most about her profession are the amazing people she works with. I always felt the same way. Though never been a particularly lucrative profession, publishing has always drawn smart, well-read, intellectually curious people who are passionate about books. You can’t find much better company than that.

August 26, 2012

Don’t Bury Publishing Yet: 8 Self-Publishing Canards

Last week, David Vinjamuri wrote athought-provoking piece on the future of publishing, entitled “Publishing Is Broken, We’re Drowning In Indie Books—And That’s a Good Thing.” The article is nuanced and non-partisan, the comments less, as respondents tend to line up behind one barricade or another; but even Vinjamuri’s article contained several canards about mainstream publishing that I see everywhere and feel compelled to address.

Let me start by saying that I’m as excited as any writer by the advent of self-publishing and the opening up of some distribution networks, as well as the ability of writers to reach readers more directly than ever before through social media. There are already several excellent applications for self-publishing, including:

1. Niche nonfiction. Books on very particular subjects with a defined readership that is too small to attract mainstream publishers can do very well as self-published books. I have worked in and been published by mainstream publishers throughout my career, but if I ever get around to writing that book on editing fiction I plan to write, I would definitely consider self-publishing.

2. Genre fiction series. Good writers who can write very quickly and keep churning out a consistent genre “product” can build a following, provided they are also smart entrepreneurs and social media pros—not a very common combination of talents, but there are some. Amanda Hocking is the poster child for this sort of writer.

3. Backlist. This is my favorite application, for purely selfish reasons. As a writer, I had two dreams: to be the answer to a clue in the New York Times crossword puzzle, and to see all my books in print at once. The first of these remains, alas, unfulfilled; but the second is happening as we speak. Simon and Schuster just released my three last novels, and another publisher is preparing to release e-books and paperback editions of the earlier titles. If my publishers hadn’t, I would have. A privilege once reserved to the top 1% of writers is now accessible to all.

No doubt as this infant industry develops, additional applications will arise. In its current state, however, it’s a more problematic choice than its advocates admit. If a writer goes into self-publishing with his eyes wide open, then good luck and more power to him. What I don’t like is seeing writers lured into an enterprise that will cost them dearly, in time and/or money, on the basis of false claims and misleading arguments. When I look at self-publishing in its current incarnation, I have to conclude that for fiction writers in particular, mainstream publishing offers important advantages over self-publishing, for reasons that self-publishing advocates gloss over or occlude. Here, in no particular order, are some of the canards I see bruited about, followed by my own take.

1. By signing with a mainstream publisher, writers give up the rights to their work forever. Not true if the writer has an agent, and most fiction writers who sell to mainstream publishers do. Their contracts include reversion clauses that return the rights to the writer if the publisher is not selling an agreed-upon quantity after an agreed-upon period of time.

2. Publishers dictate what writers can write. This claim is based on a misunderstanding of the author–publisher relationship. Publishers cannot dictate what a writer writes; they can only dictate what they will publish. That’s their right. It doesn’t stop writers from writing for other publishers and/or writing under different pen names.

3. Self-publishing is free, or almost free. Yes and no. It is free if you do it on the cheap: no design, no editing, no paid services at all. But such a book is unlikely to be worth reading and, according to a recent Taleist survey, unlikely to sell. Edited books, especially books that were previously edited and published by mainstream publishers, outsell unedited books by a wide margin. Of course, self-published writers can hire freelance editors, and many do. But good editors tend to be expensive, and a single editor cannot duplicate the editing process of trade publishers. There is also the sad fact that many self-published novels are not really editable. One would have to basically rewrite the book to make it readable. So, while writers can always find editors willing to take their money and correct their grammar, they will never find one who can make a silk purse out of the sow’s ear.

4. Mainstream publishers don’t edit their books any more. The story I hear most often is that trade publishers, in order to cut costs, have stopped editing their books and now simply proofread them. This is certainly not the case with my current publisher, Viking/Penguin, which has put my upcoming novel through three rigorous stages of editing, both concept and line editing, to its great benefit. Nor is it the experience of the many writers I know who are publishing with mainstream publishers, large and small. The level of editing is the one thing that most (not all) published writers, an obstreperous lot, are satisfied with. Duplicating that kind of attention to detail by top experts would cost many thousands of dollars. At the price-point of most self-published e-books, the great majority of writers would never earn that money back.

5. Good writers will rise above the dross of the many inferior self-published books. How is this supposed to happen? How are readers supposed to find these needles in a haystack? This year 211,269 titles were self-published, according to Bowker. Last year it was 133,036. Next year it may be half a million, and remember, the older books do not go away, so these numbers are cumulative. Most of these books are dreadful, though you wouldn’t know it by the frenzied self-promotion and circle-jerk cross-reviewing of some misguided self-published writers. There is a reason that literary agents reject 95 to 99% of submitted work. Unless you have read through the slush pile of a literary agent, you would not believe how many people who cannot write a single grammatical or coherent sentence nevertheless undertake to write a book. Many of these people are now self-publishing. I don’t doubt for a moment that there are some excellent writers in the mix. But how, in the relentless barrage of self-promotion, and given the lack of creditable reviewing of self-published books, can readers hope to find the pearls among them? In his article, Vinjamuri acknowledges the problem but predicts that reliable indie reviewers will soon arise, replacing the “gatekeepers” of mainstream publishing and reviewing. Maybe so; at least, I agree that this is what needs to happen for the industry to advance instead of implode. But given the vast quantities of inferior books flooding the market, I wonder how any reviewer could possibly sift through them all.

5. Good writers will rise above the dross of the many inferior self-published books. How is this supposed to happen? How are readers supposed to find these needles in a haystack? This year 211,269 titles were self-published, according to Bowker. Last year it was 133,036. Next year it may be half a million, and remember, the older books do not go away, so these numbers are cumulative. Most of these books are dreadful, though you wouldn’t know it by the frenzied self-promotion and circle-jerk cross-reviewing of some misguided self-published writers. There is a reason that literary agents reject 95 to 99% of submitted work. Unless you have read through the slush pile of a literary agent, you would not believe how many people who cannot write a single grammatical or coherent sentence nevertheless undertake to write a book. Many of these people are now self-publishing. I don’t doubt for a moment that there are some excellent writers in the mix. But how, in the relentless barrage of self-promotion, and given the lack of creditable reviewing of self-published books, can readers hope to find the pearls among them? In his article, Vinjamuri acknowledges the problem but predicts that reliable indie reviewers will soon arise, replacing the “gatekeepers” of mainstream publishing and reviewing. Maybe so; at least, I agree that this is what needs to happen for the industry to advance instead of implode. But given the vast quantities of inferior books flooding the market, I wonder how any reviewer could possibly sift through them all.

6 . Distribution is now open to all. True for e-books only, not print. Self-published books are seldom carried in brick-and-mortar bookstores or the other chains that now sell books, including Target and Walmart. Libraries rarely buy self-published books, and that is a huge factor, because for many mid-list writers, library purchases make up the bulk of their hardcover sales.

7. Writers make more money self-publishing than by being published. This is a complicated question that will vary from writer to writer and case to case, but most self-published writers will never earn as much as a writer with one of the Big Six publishers makes as an advance; and self-published writers have to pay out of their own pockets for services, including editing, that published writers get as part of the deal. Of course, most published books don’t sell enough to cover their advances, but the writers still get to keep the money. It’s true that self-published writers earn a larger percent on e-book sales, typically 70% of retail price as opposed to 25% for published writers. But while royalty rates are higher, book prices are lower. Which is more: 25% of $10 or 70% of $3.00? And that leaves out print sales, which are still nonexistent for most self-published writers.

8. Writers grow by putting their books out there and testing the market. This might be true if the writers were getting detailed, informed feedback on their work– not the sort they get from Amazon readers’ reviews or the paid reviews that some self-published writers resort to. The only real feedback most self-published writers get is from sales, a very blunt instrument that doesn’t necessarily correlate with quality and does nothing to show them what went wrong or how they could make their work better. Good writers thrive on detailed critical feedback from editors and serious reviewers, and they grow by doing the hard work of writing and revising for as long as it takes. My greatest concern about the ease of self-publishing is that the temptation to shove a book out into the world in its first or second draft is enormous. Even good writers succumb. The result is many bad self-published books that might have been good, and, worse yet, a few good books that might have been great.

It’s hard to see into the future, but a few things are already clear. Self-publishing will continue to evolve. It will alter long-standing trade publishing practices. It will change the balance of power between writer and publisher by providing writers with more options. But self-publishing still has one inherent flaw that will not be easily overcome: the temptation it provides writers rush prematurely into print.

It doesn’t take a weatherman to see change coming. There’s an old Jewish curse: “May you live in interesting times.” Me, I look forward to seeing what happens.

Coming soon: an interview with prominent literary agent and e-book pioneer Richard Curtis.

August 19, 2012

Digging Up Blurbs

I was looking for a book in an airport recently, just in case the three paperbacks and the hundred or so novels stored in my Kindle failed to suffice, when I came upon a novel by a writer I’d never heard of before: Witches on the Road Tonight, by Sheri Holman. The book looked interesting, and the first page passed the acid test, but what pushed me over the edge was a glowing blurb by Jane Smiley, whose work I love. I bought the book and was amply rewarded.

I remembered this incident when my editor at Viking asked if I had any suggestions for writers who might give us blurbs for my upcoming novel, A DANGEROUS FICTION. As it happened, I did know a few writers who I thought might be willing to read, which they graciously agreed to do.

But why stop there? I thought. I made a list of writers whose work I admired. Most of them I didn’t dare approach, knowing that famous and bestselling writers are besieged with such requests. The writers who remained on the list would, I knew, be difficult to reach. But with the help of my cousin the medium, I was able to make contact, and I’m pleased to report that they were all happy to oblige.

Their responses after reading went beyond anything I could have hoped for. I’m delighted to share their blurbs with you now.

“This is a brave book, with heart and guts and kidneys. This book charges straight up the hill, bayonetting all who stand in its path.” “Ernest Hemingway

“I wish I’d written this book.” Jane Austen

“A book is a book is a book, but not all books smell this sweet.” Gertrude Stein

“At last I have found my Dulcinea!” Cervantes

“Kid’s got a mouth on her. I like it.” Dashiell Hammett

“It is a far, far better book than I have read before, and nearly as good as any I have written.” Charles Dickens

“Such stuff as dreams are made of.” William Shakespeare

“I can’t wait for her next.” Homer

Many thanks to my esteemed colleagues, may they rest in peace.

A DANGEROUS FICTION will be coming out in 2013, but new editions of SUSPICION, HINDSIGHT, and ROWING IN EDEN are now available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and Indiebound.

August 12, 2012

Can Writing Be Taught?

My last post about the bloodsuckers who prey on writers stirred up some interesting discussions on writers’ forums that I frequent. One writer, Cammy May Hunnicutt, agreed that paid reviews and submission services exploit naive writers and provide no real benefit, but she questioned my assertion that the one thing worth paying for is education, learning the craft. “People,” she wrote, “are dying to think they can spend some money and become ‘good’ writers. Not really so.”

This is an interesting statement; and based on 15 or so years of teaching fiction writing, I have to agree with it, if by “good” we mean extraordinary, publishable. To get to that level, there has to be some natural ability in the mix. But talent isn’t everything; it isn’t even enough. Writers need craft, too. We don’t make it all up from scratch each time we start a story. We learn stuff and build on what we’ve learned to do more, the same as in any art. Just as painters need to master perspective, so must writers master point of view. Just as musicians must learn structure to write fugues, so must writers learn to structure their stories for maximum effect. These techniques can be taught to any reasonably literate, motivated person, so I believe that nearly everyone can learn to write better; and that is something most writers aspire to.

But Cammy, bless her, was not convinced. “‘[You say] ‘You can’t learn to be good, but can learn to be better.’ Let me ask you how much that counts for. You see writers who are really sweet and don’t get published, others who write junk and make millions. If I can use athletics as a metaphor, I’ve seen the workshops and camps and coaching. And being ‘better’ is seldom good enough at the level that the average person can access. I don’t see it as an investment that will return, but a money drain.”

Cammy asks tough questions, but fair ones. It’s true that all the training in the world isn’t going to get a mediocre hoopster onto the Knicks. Writers who study with me are strongly motivated—they have to be, to participate in my strenuous workshops—and over the years, quite a few have gone on to publish. I take enormous pleasure and pride in their success–but they are a minority. The hard truth is, many of my students will never publish unless they self-publish. The bar to trade publication is extremely high, and even for the most talented, there are numerous obstacles along the way. So what is the point of writing classes for those who won’t achieve that? Could teaching itself be exploitative?

Cammy asks tough questions, but fair ones. It’s true that all the training in the world isn’t going to get a mediocre hoopster onto the Knicks. Writers who study with me are strongly motivated—they have to be, to participate in my strenuous workshops—and over the years, quite a few have gone on to publish. I take enormous pleasure and pride in their success–but they are a minority. The hard truth is, many of my students will never publish unless they self-publish. The bar to trade publication is extremely high, and even for the most talented, there are numerous obstacles along the way. So what is the point of writing classes for those who won’t achieve that? Could teaching itself be exploitative?

I don’t believe it. People deserve a chance to strive for their goal, however difficult it may be. Besides, you can’t always tell who will and who won’t end up getting published. I’ve been surprised more than once. Sometimes a genre gets really hot and the bar is lowered a bit as publishers scramble for material, so that agents and editors may be willing to take on a manuscript that needs more work than they’d normally invest. Other times I’ve seen students who start out with major deficits learn really, really quickly—just soaking things up because they’re ready for them. (See Mika’s story.)Where a writer starts isn’t necessarily an indication of where she’ll end up.

Some of my students are going to end up self-publishing their work–a statistical certainty these days. In those cases too, I think they’re doing a good thing for themselves and their books and their eventual readers if they learn all they can about the craft of writing. Doesn’t have to be through classes, either. A detailed critique by an editor or writer with serious chops (scroll down on this page for a list of things to look for in a writing teacher and editor) can be an eye-opener, serving not only to improve the work in question but to provide the writer with tools they can apply to everything they write thereafter. If that’s not in the budget, there are excellent books on writing available, and libraries where they can be had for free.

To me it seems self-evident that writers, like painters and musicians, need to master the tools of their trade; but, as Cammy was brave enough to point out, I have a vested interest in believing this. So let me ask the writers among you to weigh in with your thoughts and experience on Cammy’s challenging question: Can writing be taught?

My purpose here is not to tout my classes; in fact, I’m taking a hiatus from teaching and editing for the next 4-5 months to work on a book. If, however, you are interested in taking one of my workshops when I resume, the best way to get in is to get on my emailing list, which you can do by emailing me at www.nextlevelworkshops dot com.

August 5, 2012

Publishing Mosquitoes

It’s a bad year for mosquitoes – or rather, a great year for mosquitoes, a bad one for their prey. On Long Island, where I live, I can’t step out to the garden without being attacked. There’s a wooded park nearby where I like to take the dogs for long, off–leash walks. Last couple of times I tried, I longed for one of those veiled hats that women explorers used to wear. I spent the entire walk waving my hands in front of my face, batting the pests away.

I thought of those mosquitoes when a former student (thanks, Deniz!) sent me a link to a service that offers, for an hourly fee of over $100, to match writers with literary agents. What’s wrong with that? you may ask. If you do, I’m glad you’re reading this post, because this is also a bad year for purveyors of unnecessary services to writers. It’s money they’re after, not blood; but how much of either can writers spare?

Writers who’ve invested time, effort and emotion in writing a book desire to see that book published with a passion like that of people who long for a child. Desire of that magnitude makes people vulnerable to hucksters. Of course, hucksterism on the fringes of publishing is not a new phenomenon. Long before the advent of inexpensive self-publishing, vanity publishers existed to fulfill the dreams of aspiring writers, at a hefty price. Distribution was never part of the deal, so most often those writers ended up with boxes of unsellable books in the garage. Today, writers can distribute their self-published books through the same online channels as trade publishers, and they have far more tools to communicate with potential readers. The market is booming, and so is this year’s crop of mosquitoes.

I was a literary agent for many years and have been a writing teacher for many more. I feel protective toward writers and I don’t like seeing them ripped off. Today I’m going to look at just a couple of the services currently offered to writers. Take, for example, the submissions service I mentioned earlier, which promises to expedite the (admittedly tortuous) process of getting a literary agent.

In fact there are numerous companies that offer the same service, and they exist for a reason: it’s not easy to get an agent, or to sell your book without one. Unless they have an introduction from client or publishing professional, writers need to work hard just to persuade agents to read their manuscripts. Most submissions are rejected at the query stage…but not all. If the work is good enough, and the writer goes about searching in a smart way, finding an agent is definitely doable. Many of my students and forum friends have found agents in recent years, and several had multiple offers of representation. This, by the way, is why when agents decide they want a book, they tend to act very quickly: they assume that if they are interested, others will be, too.

Agents are still reading, searching and hoping for the next original voice. (See this interview with literary agent Gail Hochman.) Writers need to learn to present their work professionally: polish the manuscript till it shines, research agents, writes a good query letter. Excellent books and websites abound with guidance on how to do that. (Here is a list of some of my favorites.) Any service that guarantees to find writers an agent probably has some snake oil and a bridge or two for sale. Even the ones that don’t guarantee it imply that their service makes it more likely. Not so. If the work isn’t first-rate, no intermediary will be able to persuade a legitimate agent to invest time in it. If the work is good enough, agents don’t need an intermediary to point that out.

Agents are still reading, searching and hoping for the next original voice. (See this interview with literary agent Gail Hochman.) Writers need to learn to present their work professionally: polish the manuscript till it shines, research agents, writes a good query letter. Excellent books and websites abound with guidance on how to do that. (Here is a list of some of my favorites.) Any service that guarantees to find writers an agent probably has some snake oil and a bridge or two for sale. Even the ones that don’t guarantee it imply that their service makes it more likely. Not so. If the work isn’t first-rate, no intermediary will be able to persuade a legitimate agent to invest time in it. If the work is good enough, agents don’t need an intermediary to point that out.

All these submission services do, in my opinion, is impose an extra layer between writers and publishers. Their expensive guidance is based on free data bases available to any writer with an Internet connection; Agentquery’s, for example. For more on this topic, see Victoria Strauss’s article on Writers Beware.

There are many species of publishing mosquitoes. Some varieties (Anopheles scribus) specialize in self-published writers. It hurts me to hear about writers paying hundreds of dollars for reviews from bloggers or companies like Kirkus Indie Book Reviews. The purveyors of this service are exploiting a weakness in the self-publishing industry: the difficulty in finding readers when your book is one drop in a sea of millions of self-published works. Eventually, I expect, legitimate reviewers of self-published work will emerge with sufficient clout to sell books. Paying for a review of your own book is no substitute. Before writing this post, I read a whole batch of these reviews from the better-known sites, which claim to be impartial. I found several things in common. The reviews are primarily plot summaries, as if to prove the reviewer had actually read the book. Then the reviewer said some nice things and some mildly critical things about the writing. No matter how negative the overall review, there was always a line that the writer could extract as a blurb.

Writers, save your money. Paid reviews have no credibility, and I don’t believe they sell books. The only review worth having is an impartial one from someone not paid by, related to, or sleeping with the writer. Better to invest that money in learning the craft. Take a writing class or find an experienced editor with a track record to work on your book with you. (Scroll down on this page for a list of criteria to look for in writing teachers and editors.) The best way to sell a book is still to write a really good one.

July 28, 2012

The Five Qualities Writers Need

Today I’d like to start by introducing you to a wonderful writer, Mika Ashley Hollinger, whose first novel just came out with Random House. I have a very personal relationship to this book and its author. Mika was my student for several years while she worked on PRECIOUS BONES, so I feel about this book as a midwife feels about the babies she helped deliver. But friendship and admiration aside, I think Mika’s own publishing story is an instructive and inspirational one for all writers.

Barbara: Tell us a little about your novel, PRECIOUS BONES. What’s it about?

Mika: PRECIOUS BONES is a young adult historical fiction, about a ten-year-old girl growing up in the Florida swamps of 1949. I did extensive research on the life cycle of Florida’s swamps and inhabitants. It was at one time an incredible wildlife habitat and I wanted that time to be forever remembered.

The book’s setting feels entirely real. Did you grow up in the Florida of that time? Is the novel based on your own life?

Yes, I was born and raised on the east coast of southern Florida. The book is loosely based on my childhood memories. I chose 1949 because that was just the beginning of Florida’s drastic changes, both environmentally and socially. After being away many, many years, I returned to visit where I grew up and was devastated by the changes that had taken place. It woke up all those memories.

Yes, I was born and raised on the east coast of southern Florida. The book is loosely based on my childhood memories. I chose 1949 because that was just the beginning of Florida’s drastic changes, both environmentally and socially. After being away many, many years, I returned to visit where I grew up and was devastated by the changes that had taken place. It woke up all those memories.

Did you read much as a child? What were your favorite books?

I loved to read stories about animals and about the South. Some of my favorites were; The Yearling, Charlotte’s Web, Gone With the Wind and of course To Kill a Mockingbird. I was fifteen years old when I saw the movie and it had such a profound effect on me, I knew from that moment on I wanted to write books. I wanted to tell stories from the innocence of a child, but with the wisdom of an adult.

When did you first start writing PRECIOUS BONES?

About twenty years ago I started compiling memories and facts about Florida and my childhood. It didn’t actually become a story draft until I took an online Writer’s Digest course in 2004 with you, as my teacher! From that experience I gained the confidence and knowledge that I could actually write this story.

When was it published?

It was published by Random House in May 2012.

How many drafts of the novel did you write?

I would say there were at least three or four along the way, I don’t really remember. Of course, my most serious and extensive re-writes were with my agent and then my editors at Random House.

Was the path to publication smooth? What kept you going?

The path to publication was a long and winding road filled with speed-bumps. I have a folder filled with rejection slips. I had two different agents, at different times, but neither one knew where or how to sell the book to a publisher. There were some very discouraging times and on more than one occasion I thought about just giving up. But through the support of my husband, and your support and encouraging advice, I stuck with it.

Before the book sold, did you ever consider self-publishing?

No, that was not a consideration. I held true to my own conviction that it had go through the proper channels and be published.

What sort of strategy did you have before selling PRECIOUS BONES?

In hindsight, one of the problems, from 2005 to 2010, was I didn’t have a strategy. I was so new and naive that I just sent queries out to any agent. I got a lot of positive response, which led me to believe I did have a good story, but no one knew how to sell it. After one particularly discouraging event, I told my husband I felt like it was a hopeless situation. His advice to me was, do some research and find agents that represent the type of story you have, and that is exactly what I did. I read young adult books with a southern theme, and stories with the same type descriptive writing style I was using. I sent out a few more queries. There was one agent in particular whose work I so admired. Within six weeks, I got a phone call from her and I had the agent of my dreams: Catherine Drayton of Inkwell Management. She was wonderful to work with, she understood what needed to be changed or added to make the story bigger. We worked together on a couple of rewrites and within one year she had it sold to Delacorte Press, Random House Children’s Books. A true dream come true!

Tell us about the phone call…was it a call?…in which you learned the book had sold.

Catherine kept me informed on all transactions, which relieved a lot of anxiety on my part. On February 24, 2011 she emailed me with the wonderful news that Michelle Poploff of Delacorte Press, loved the story and wanted to publish it. It’s one of those moments when you have to read the sentence over and over again to let the true sense of its meaning sink in. Working with Michelle and her assistant Rebecca Short was also an incredible experience. These ladies were so professional and accommodating. Getting published with a house like Random House was well worth the wait.

What have you learned as a writer from the evolution of your first novel?

Believe in yourself. Be prepared for those rejection slips and just file them away. And when you do sign with a publisher, be ready and willing to listen to their advice and suggestions. There may be some major changes taking place with your story. Work with them, it’s what they do; they know how to take your little story and turn it into a bigger one.

Believe in yourself. Be prepared for those rejection slips and just file them away. And when you do sign with a publisher, be ready and willing to listen to their advice and suggestions. There may be some major changes taking place with your story. Work with them, it’s what they do; they know how to take your little story and turn it into a bigger one.

What advice do you have for other aspiring writers?

Persevere. No one is going to come looking for you, you have to look for them. Do your research and find agents that represent your genre of writing!

What comes next for you?

I am working on another young adult historical fiction, set in Georgia in 1969, during the height of hippies, The Vietnam War and integration.

I can’t wait to read it. Thanks, Mika!

I wanted to bring Mika and her novel to your attention for several reasons. First, because PRECIOUS BONES is wonderful, one of the best young adult novels I’ve ever read. Over the course of its evolution I read it multiple times, and it still makes me cry. It’s a book that children and adults can enjoy equally, and I recommend that you buy it immediately. It’s available as an e-book, but I’d suggest getting a print copy, because I have a feeling that first editions of this book will someday be valuable.

The second reason is that Mika exemplifies the five qualities I believe writers need if they aspire to be published, as her story illustrates.

Talent is the first requirement. Anyone can learn craft, and even the most talented writer needs to do that; but talent is a gift, just like athletic ability and perfect pitch. Mika had talent in spades. The first time I read her work, when it was little more than a gleam in its author’s eye, she was in a class of 10 or 12 writers. Even in its embryonic form, I still remember how her language, descriptions and characters jumped off the page.

Craft is the second. Serious writers study the craft. Mika invested in her dream and became a better writer than she was. These days, with self-publishing is popular as it is, there are lots of people offering all sorts of services to writers. In my opinion, the only thing a writer ought to pay for is good instruction in the form of classes or manuscript evaluation.

The ability to learn from good criticism is the third requirement. You can only go so far on your own. At a certain point you must seek out discerning readers, learn to distinguish good criticism from bad, and implement the good advice. Criticism is like fertilizer; it can be hard to abide, but it grows the writer. Mika was open to that process.

Perseverance is the fourth requirement. Mika’s novel was 20 years in the making, eight years in the writing. She had agents who failed to sell the book and many disappointments along the way. She could have given up at any point. She didn’t. She believed in her book. If the author doesn’t, who will?

A focused goal is the fifth. Mika was determined to be published by a trade publisher. She did her homework and focused on agents who represent her type of writing. Agents and editors bring real value to their books. Because Mika held out for commercial publication, PRECIOUS BONES is a much better book than it would have been if she had self-published an earlier version–and I say that as someone who read and loved the earlier versions.

PRECIOUS BONES is available on Amazon and B&N. Order it now, or at least read an excerpt and decide for yourself. What was that Sandra Bullock line? “You can thank me later.”

If you’re a fiction writer willing to work hard to improve your craft, give me a shout. I offer several online writing workshops through my Next Level website.