Barbara Rogan's Blog, page 8

January 8, 2013

Cross-Writing: Gender Bending Through Fiction

I read a good book lately, and it got me thinking, as good books tend to do. The book was RESTLESS, by British novelist William Boyd, and it’s about two women, a mother and her grown daughter. The mother had a secret history as a spy in World War II, which she reveals to her daughter through journal entries. The story unfolds through their alternating points of view.

At some point, it occurred to me that these two fully realized female characters, and their voices, were created by a man. Nothing in the novel tipped me off; no false note ever sounded. This male writer had successfully channeled two perfectly convincing women. And what struck me about this feat is that it was both unexceptional and magical.

Unexceptional in that most good writers do it all the time. They have to; a writer who can write from the perspective of only one sex is badly handicapped. Not every attempt succeeds, even among the great. Hemingway wrote one of the most laughable female characters I’ve ever read. Of coure, he also created Lady Brett Ashley, offsetting that other failure, but not even she got her own POV. On the other end of the scale, romance novelists have a tendency to create male characters who would never survive outside the rarified pages of romance novels. Nevertheless, creating convincing characters of the opposite sex is one of the tricks of the trade, so common as to pass unnoticed most of the time; ii’s the rule rather than the exception.

Yet it’s also magical, if you think about it, this gender alchemy. Fiction writers constantly project themselves into characters different from themselves, one might argue; what’s so special about this difference? I would answer that gender is the first identifier, the most basic differential. Its primacy is revealed in the language. When we describe ourselves as “a white Jewish male” or a “conservative Southern woman,” gender is the noun, while the other descriptions are adjectives. “The other half” means the opposite sex. Countless tomes have been written explaining men to women and women to men. “Write what you know,” writers are constantly told; but who among us, apart from transsexuals, really knows what it’s like to inhabit the world as the opposite sex?

So how do fiction writers pull it off? To create any character, you have to get inside him: walk in his shoes, see through his eyes. This is true whether or not the writer uses that character’s POV. As writers we draw not only on our own experience, but also on observation and imagination. Thus the ability to create convincing characters of any gender, let alone the opposite one, is not something we’re born with. Rather, if my experience is typical, it’s learned incrementally.

Like most writers, I started out writing from the POV of a character of my own gender. That sufficed for the first book, but not the second, CAFÉ NEVO, which required a wider palette and multiple POV’s. That was a long time and many books ago, but I still remember the exhilaration and trepidation of those initial forays into the Other.

I started out, as I did with every character, with the things we had in common. One of my male POV characters was a writer, so right away I knew understood some things about him. That character was also a parent, and not a monstrous one; that is, he loved his son. His method of expressing it might be different, but love is love. All the basic, deep emotions are felt by both sexes, and that is a lot of similarity to work with.

But then I also had to think about the differences between my male and female characters, insofar as those differences were gender-based. Every character is an individual, but gender is a big part of who we are. I’m not going to start cataloguing those differences or figure out the relative roles of nature and nurture; suffice it to say that a writer who fails to take these differences into account is unlikely to create convincing characters of the opposite sex. So, too, a writer who fails to take the commonalities into account. In A FAREWELL TO ARMS, Hemingway seems to regard women as an altogether different species from men; his Catherine Barkley is, in my opinion, a mere plot device meant to showcase the travails of the real, i.e. male protagonist. (Sorry to keep busting on Papa, especially as he was kind enough to blurb my upcoming book, A DANGEROUS FICTION, but I’m still smarting from that ludicrous childbirth/death scene in the end of that book, which could have been written for Downton Abbey. Not that I don’t love Downton Abbey, but still.}

Any writer who wants to grow needs to write credible characters of both sexes. But forget “needs to;” the primary reason for doing it (and for writing in general) is that it’s huge fun. Writing enables us to transcend all sorts of boundaries. I will never be a man; that direct experience is denied me in this lifetime. But I can inhabit my male characters, and through them I can shoulder my way through the world; experience male friendship; get into fights; size up a woman and calculate my chances; feel a father’s love and widower’s agony; fall in love as a boy and look back on it wistfully as an old man. Cross-writing’s a bit like cross-dressing, but writers go deeper, donning bodies and souls instead of just clothes. And just as real-life experience feeds fiction, so does fiction enrich real life.

I’m interested in other writers’ experiences in this area. Do you write viewpoint characters of the opposite sex? How do you take their gender into account, if at all, and what have you learned through your adventures in cross-writing?

December 26, 2012

“Too Much Body Language,” She Said, Frowning.

There’s a secret to getting a first novel published, and it has nothing to do with platform, connections, or the ebb and flow of publishing’s tides. Not that those things don’t matter. They do matter as secondary factors, but only if a prior condition is met: the novel itself needs to be irresistible.

I’ll give you an example from my years as a literary agent. I once received a manuscript that by every reasonable standard should have been rejected at first glance. Not only was the ms. full of handwritten corrections, it was actually printed on the back of previously used paper. Someone who couldn’t be bothered to submit a clean copy was unlikely to have written anything I could sell. I glanced at the first sentence, just to confirm my expectations. Then I read the next line, and the next. The voice was strong and authoritative, the voice of a writer who knows he’s got a story to tell and the chops to tell it. I took the manuscript home with me and finished it that night. It was an extraordinarily entertaining Western about a Jewish peddler whose quest for the lost tribe of Israel takes him into Indian country: a sort of Jewish “Little Big Man.” It wasn’t perfect, but the story was like nothing I’d read before, the characters were fully realized and fascinating, and the scenes were wonderfully crafted. I called the writer the next day and offered representation.

In an industry that agrees on very little, there’s near unanimity on the best route to breaking into print. In a recent interview with Viking editor Tara Singh, I asked, “What’s the most important thing writers can do to help themselves get published?” This was her response:

“I think the most important thing a writer can do is to write a really good book. This may not be a very helpful answer, but it really is the most important thing. Have others read your work, go to writers workshops, put it away and come back to it if you need to, but make it good.

Beyond that, I do think that publishers are paying much more attention to whether or not an author has an online presence. Is he or she active on facebook? Does he or she have thousands of twitter followers? That said, most writers won’t have that and I think that if you spend your time worrying about creating an amazing online presence rather than writing a really good book, you’d be spending your time poorly.”

So all I have to do is write an irresistible book, you may be thinking. Brilliant. And just how do I do that? But please note that I said irresistible, not perfect. No book ever emerges perfectly formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead. It’s a process, and good writers are grateful for the input of good editors. So you don’t have to write a perfect book, which I hope is reassuring, just an irresistible one. What makes a book irresistible is, for me, a combination of things: an original story; interesting characters who jump off the page; and the mastery of craft required to do that story justice.

Writers are expected to master that craft on their own dime, not the publisher’s. For that reason, I’m inaugurating an occasional series of craft tips for fiction writers, many drawn from the writing courses I teach online at Next Level Workshops. These are not intended as proclamations from on high or any sort of writing orthodoxy, but rather as distillations of lessons I’ve learned over 30 years as a writer, literary agent and editor. I hope you find them useful.

LESSON ONE: BEATS VS. DEADBEATS

A beat, for the purpose of this discussion, is everything in a passage of dialogue except the spoken words and speaker attribution (he said, she asked, etc.) That would include bits of description, interior monologue, action, and the nonverbal parts of conversations, aka body language.

Dialogue needs occasional beats for rhythm and to bring in other dimensions of the scene. How many beats a writer uses is a matter of personal style. Stretches of straight dialogue can be useful to allow readers to really hear the characters’ voices in their heads without constant interruption. But if you overdo it, you impoverish the scene, you take away its physicality. The effect for the reader is like listening to a TV with no picture.

A deadbeat is a beat that brings nothing to the party, or at most a measly can of beer. If a beat doesn’t contribute something meaningful to the scene, beyond what the dialogue itself conveys, find a beat that will.

A deadbeat is a beat that brings nothing to the party, or at most a measly can of beer. If a beat doesn’t contribute something meaningful to the scene, beyond what the dialogue itself conveys, find a beat that will.

It’s my contention that most—not all, but most—descriptions of body language fall into the category of deadbeats. They’re the fallback beat, the first ones most writers resort to. And to some extent they’re necessary; without them, we’d miss some nuances, especially when the characters’ expression or body language contradicts what they’re saying. The trouble arises when writers overuse or misuse them as a means of telling what the character feels in the guise of showing. Like weeds, deadbeats tend to crowd out beats that would actually enhance the garden.

It’s easiest to show with an example. Here’s a short passage in three variations.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he said.

“Suit yourself,” she said.

The lines of dialogue are evocative, but it’s not clear how the speakers mean them or what’s going on underneath the words. Suppose you, as the writer, want to keep the dialogue but add to it. If you’ve fallen into the habit of reaching first for body language, your next version might read like this.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he said, frowning.

She waved an airy hand. “Suit yourself.”

More information is conveyed, to be sure, but at a price. You’re now basically telling the reader how the characters feel, instead of letting them feel it themselves. And you’re not adding a lot. We already know the male speaker is unhappy, so “frowning” is a deadbeat. Her “airy wave” is a bit better, but her line itself is already dismissive. Another deadbeat, this one bearing a measly can of beer.

So you cross out those lines and reach further afield for an image that will illuminate, and you come up with a third variation.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he said.

She kept her eyes on her magazine, though she wasn’t turning any pages. The room was silent but for the faint, mournful whistle of a freight train.

“Suit yourself,” she said at last.

That mournful train whistle conveys a sense of melancholy, and the mention of a train suggests a crossroad. The woman’s pretense of reading shows the disconnect between two people who seem once to have been connected. Suddenly these spare lines of dialogue are imbued with a sense of parting and finality; and readers will feel it.

Capisce?

I’m taking a brief hiatus from teaching and editing for the next 4-5 months to work on the sequel to A Dangerous Fiction; but I’ve always got one eye out for serious students of writing. If you think you might be interested in taking one of my workshops when they resume, the best way to keep that option open is to get on my (nonspamming!) emailing list, which you can do by sending me a note at www.nextlevelworkshops dot com. The classes are small and intense (see testimonials) and I only offer a couple a year. Lately I’ve had more applicants than I can accommodate, but the first notice always goes out to folks on that list.

December 19, 2012

MY YEAR IN BOOKS

It’s the time of year for lists and gift-giving, so I’m combining the two in this list of novels I loved this year. They’re not necessarily books that were published during 2012; in fact, some of them go back a decade or more (which shows you how far behind I am in my reading.) They belong to no particular genre, but are simply my favorite ten books among the hundred or so I must have read this year, chosen because they blew me away and sent me scrambling to find other work by the author. As much as we moan and groan about the publishing industry, there is certainly no dearth of good fiction out there. I hope you find some books here that you’ll enjoy reading and giving.

OBLIVION by Peter Abrahams. This 2009 thriller features a brain-damaged detective. It works on every level.

BORDER CROSSING by Pat Barker. I believe I’ve read every book Pat Barker has written. She’s a writer’s writer, and one of the greatest living English writers, in my not-so-humble opinion.

THE SISTERS BROTHERS by Patrick deWitt. Comic and tragic, a skewed Western.

THE SISTERS BROTHERS by Patrick deWitt. Comic and tragic, a skewed Western.

THE SCOTTISH PRISONER by Diana Gabaldon. Gabaldon is the most generous of writers, and this novel featuring Lord John Gray is no exception.

GAME OF THRONES by George R. R. Martin, plus sequels. Don’t start this series unless you have a month or two to spare.

STILL LIFE by Louise Penny. This is actually the first in her mystery series starring Chief Inspector Armand Gamache of the Sûreté du Québec. Like I said, I’m behind on my reading. But having read the first, I’m scrambling to catch up.

THE DEVIL ALL THE TIME by Donald Ray Pollock. Set in the mid-1900’s, Pollack’s book has totally deranged killers, a cast of grostesque but fascinating characters and an unlikely hero.

GONE GIRL by Gillian Ryan. Super-clever page-turner about the world’s most dysfunctional marriage. I also loved her earlier books.

THE EIGHT DWARF, by Ross Thomas. Thriller set in post WW II, wonderfully written with unforgettable characters.

THE PATRICK MELROSE NOVELS by Edward St. Aubyn. This collection of related novels contains the most brilliant writing I read all year, and he sure doesn’t shy away from the hard stuff.

That’s my list. How about you: what stand-out books did you read this year?

December 11, 2012

Galleys!

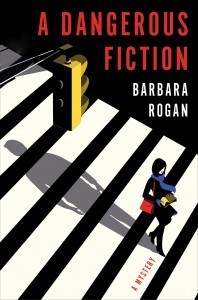

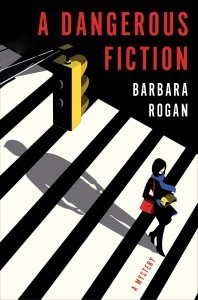

There are a few big milestones in the publication of a book. Selling it is the first, of course–getting that fateful phone call from one’s agent. The next is finishing the final edit–letting the book go at last. The third is receiving bound galleys in the mail: suddenly your brainchild is an actual, physical book, cover and all. And that, dear reader, is what happened today. The galleys of A DANGEROUS FICTION have arrived, and I’m thrilled to death. Here’s the cover:

A DANGEROUS FICTION will be out next summer via Viking Press, but the book is available for preorder already on Amazon and Booksamillion. No reviews yet, of course—but check out these amazing blurbs from fellow-writers. The latest, not yet posted, is from bestselling author J.A. Jance:

“Clearly, the most dangerous fictions are the ones we tell ourselves.”

It’s a good day.

December 2, 2012

10 Things Writers Should Expect From Literary Agents

Gone—long gone—are the days when writers finished their manuscripts, wrapped them in brown paper and mailed them to Mr. Doubleday or Mr. Lippincott. These days, major publishers rely on literary agents to prescreen manuscripts, and most won’t accept direct submissions from writers. That means that the first step for writers who seek mainstream publication is to seek an agent. As seasoned query hounds know, this is not as easy as opening the Yellow Pages; in fact, it’s often the hardest part of the publishing process. There are, at any given time, a few hundred agencies with the ability to get books looked at by these publishers. Last year, some 250,000 books were published in the U.S., as well as another 650,000 or so that were self-published, which gives you an idea of the number of aspiring writers out there.

You do the math. With so much demand, it’s no wonder aspiring writers obsess over the best way to catch a literary agent. The internet is full of advice for doing this, including my own articles and blog posts. But there’s precious little said on what to expect once you’ve snared the elusive beast—specifically, what to expect from it. In the heat of the search, it’s easy to overlook the fact that the agent-writer relationship is a two-sided, mutually dependent relationship. As someone’s who has worked on both sides of the street, I thought it might be useful to assemble a little list of what writers can expect from their agents.

Enthusiasm for your book. If they don’t love it, they won’t have the fortitude to stick with it even if it doesn’t sell immediately. This enthusiasm should be accompanied by a realistic appraisal of the book’s prospects. In general, part of the agent’s job is educating the writer about how the industry works.

A plan. He or she should have some idea of editors who might like your work.

Commitment. If a book doesn’t sell in the first round of submission, the agent should have a back-up plan. If she’s received some “close but no cigar” responses with useful feedback from the editors who declined the book, or if she has some editorial suggestions of her own, the agent and writer might want to consider a revision before making additional submissions. Otherwise, the agent should send the book out to additional publishers. How long to keep going can be a point of friction between writer and agent, as top agent Gail Hochman explains in this frank interview. Writers often want to keep going long past the point of no return, and naturally so; they have a lot more skin in their books. But at the least, those first few rounds of submission should cover a substantial number of publishers. Agents who conclude on the basis of a mere handful of rejections that the book is not worth submitting further do their clients a great disservice.

Execution. I knew an agent once who took on a writer with no clear idea of how to sell her. The ms. sat gathering dust on his shelf for a full year while he deliberated. This is inexcusable. Once an agent accepts your book, and you have a “final” version ready for submission, he needs to send it out.

Communication. Writers have the right to know to whom their work has been submitted; if the agent doesn’t offer this information, it’s perfectly reasonable to ask. Writers also have the right to be kept informed of the results of those submissions, including, if they choose to see them, copies of the rejection notes.

Contract negotiation and vetting. This is one of the most important functions of agents. Publishing contracts are long and complicated, and good agents are experts in them. Their job is to negotiate on your behalf, obtain the best terms possible, and then vet the contracts thoroughly.

Sub Rights. The agent is responsible for submitting the book to whatever subsidiary markets (film, translation, etc.) they’ve reserved on behalf of the writer, and the writer has the right to know what the agent is doing in that regard and to offer input, while bearing in mind the agent’s expertise.

Payments from publishers should be passed through promptly, after agents deduct their commission.

Advocate. The agent should continue to act as the writer’s advocate throughout the publishing process, staying involved in all phases of the process. A great deal of friction between writer and editor can be avoided by funneling questions and concerns through the agent, who can act as a sounding board and let the writer know what’s realistic and what’s not. If there is a real problem, the agent has more clout and in-house contacts than the writer.

Career guidance. Some writers want it, others just want to be left alone to write what they want to write. Either way, the agent should be the first person to whom the writer turns for education and advice about the publishing business. To this end, there needs to be good communication between them. Writers need to respect the agents’ time—the good ones are always harried, and calling them just to chat about the state of publishing or personal matters is not considerate behavior. But they also need to feel free to address professional concerns with their agents, and to be confident of getting a timely, thoughtful response.

Notice what I did not include on this list: editorial feedback. Some agents give extensive notes, in an effort to get the work into the best possible shape before submitting. Others accept only work that is already polished and salable, and leave the editing to editors. I’ve had agents from both camps. Neither approach is right or wrong; each agent decides according to his or her strengths and time limitations.

Let me know what you think. I’d love to hear from agents as well as writers. Do you agree, disagree? What have I omitted?

November 27, 2012

Location, Location, Location

The three most important things about property, agents will tell you, are location, location, and location. It occurred to me recently, for reasons I’ll get into in a moment, that this adage applies not only to real estate, but also to not-so-real estate: the settings of novels.

A few weeks ago, I was in Israel. I’d lived in Tel Aviv for twelve years, and had been back many times since, but this time we were there for the happiest of reasons: the marriage of our son. As the family was going over en masse, I had arranged for the rental of a large Tel Aviv apartment that, coincidentally, was five doors down from the house in which my husband and I lived when aforesaid son was born. It seemed an auspicious location, so I was disappointed to hear from the landlord, a week before our arrival, that the building was undergoing a major renovation with all the attendant noise and dust. He offered us an alternative: an apartment on tiny Byron Street—two doors down from my husband’s childhood home. Which just goes to show what Tel Aviv is like. Though it’s grown tremendously in the nearly thirty years since we left, at heart it retains its villagy feel. Every place evokes other places, other times; and people know each other. Instead of seven degrees of separation, it’s two or three, tops.

On the last night of our stay, we went out for a final stroll down Dizengoff. Most of the shops had changed hands since we’d lived there, but the mix of cafés, boutiques, bookstores, galleries, tourist shops and juice bars seemed roughly the same. I’d bought my wedding dress off the rack in one of those boutiques, gone now, and celebrated with a torte at Café Royal, the best pastry shop on Dizengoff, and a haven for Tel Aviv’s “Yekkes”—German Jews. Just remembering that cake made my mouth water, but the Royal was gone, too, as was its grungy nemesis across the street, Café Kassit.

Grungy it may have been, but Kassit was the social nexus of Tel Aviv’s cultural and intellectual worlds, the café where all the writers, artists, publishers, playwrights and poets sat. In Steimatzky’s bookstore, a few stores down, a person could peruse new releases in the Hebrew literature section, then walk down to Kassit and find half the authors sitting there. If a missile had struck the cafe on a Friday afternoon, Israeli culture would have been pulverized.

Grungy it may have been, but Kassit was the social nexus of Tel Aviv’s cultural and intellectual worlds, the café where all the writers, artists, publishers, playwrights and poets sat. In Steimatzky’s bookstore, a few stores down, a person could peruse new releases in the Hebrew literature section, then walk down to Kassit and find half the authors sitting there. If a missile had struck the cafe on a Friday afternoon, Israeli culture would have been pulverized.

But intellectuals weren’t the café’s only patrons. Kassit had started as a workers’ lunch stand when Dizengoff was just being built, and you didn’t need a college degree to drink there. Politically it canted hard left and secular, but in that it was a microcosm of Tel Aviv as a whole. Where you sat was who you were, and bad behavior abounded. Sitting in Kassit on successive Friday afternoons, you could track as if by stop gap photography the progress of liaisons and feuds, flirtations and rivalries.

In those days I was a literary agent by day, writer by night. I worked too hard and made too little to spend much time in cafés, but when I did meet friends or clients outside, there was never a question about where. My second novel was conceived in Kassit, and set there.

I called it “Café Nevo,” but any Tel Avivan would have recognized Kassit, home to a disparate set of lost souls whose lives converged within it. Café Nevo was both a haven and, like its Biblical namesake Mount Nevo, a vantage point onto the unattainable. Madeleine L’Engle called the book a fugue; which (leaving aside the wonder of Madeleine L’Engle calling it anything at all) struck me a smart and accurate analogy for the novel’s structure. My café was modeled on Kassit, not the thing itself, which could not have been encompassed in a novel; but it was also a tribute to an institution I’d thought would last forever. But Kassit was gone, long gone. It existed only in the memories of its patrons…and, in a way, between the pages of my novel, where its fractious customers are forever presided over the café’s tyrannical waiter and secret owner, Emmanuel Yehoshua Sternholz.

I thought about this, as we strolled along Dizengoff on that Saturday night. The city was coming to life all around us, rousing from its long Shabbat nap. Stores were opening, cafés spilling out onto the pavement. Bicycles darted between pedestrians, scooters between cars. It was time to eat. Between Frishman and Gordon, we stopped at a café and took an outdoor table. Inside, the restaurant looked shiny and metallic, with sleek European design. The place felt familiar, though I was certain I’d never been here before.

My husband looked up and down the street. Then he beckoned the waitress, young enough to be our grandchild. “Wasn’t this Café Kassit?”

She looked blank. “Before my time, if it was. I’ll ask.” She was back in a moment with the answer. “It was Kassit, a long time ago. There’ve been two different owners since.”

We looked at each other. “Like homing pigeons,” my husband said.

Cafe Nevo was published in 1987 by Atheneum and reprinted a year later by Plume Books. I’m delighted to announce that it will soon be reissued as an ebook and in a new paperback edition. In the meantime, used copies are readily available through Abebooks.

November 21, 2012

Home Again

Just wanted to let you all know that I’m back from my trip, which turned out to be a tour of riot zones, starting with Athens, which is undergoing tremendous turmoil. From our hotel, you could see the people massing for a march on Syntagma Square to protest the latest austerity measure imposed by the EU as a condition for a fiscal bailout. They have fierce demos in Greece, on both sides, with firebombs, molotov cocktails, fire hoses and police beatings. While we were there, a general strike closed everything down: all transportation, pharmacies, tourist sites, even traffic control in the airport. So much for our plan to tour the islands; but there was plenty to do in Athens, including the newly opened, world-class Acropolis Museum. Then we went on to Barcelona, where I’m told that the unemployment rate for people under 35 is an unbelievable 50%! Who wouldn’t riot? But the demonstrations we saw there were subdued and focused mainly on the rash of evictions that has resulted (naturally) from the general unemployment.

But our trip started in Israel, where we went for the wedding of our son, Jonathan, and his lovely bride, Ayana. No riots there…but now, two weeks later, the country is being bombarded by missiles from Gaza: over 800 in the past month. Apart from the personal anxiety for our family, this development leaves long-time leftists like me speechless. For years I advocated withdrawing from the Occupied Territories. In 2005, Israel finally withdrew from Gaza unilaterally, dismantling Jewish settlements and returning all the land to the Palestinians…and this is the result. It’s hugely disheartening that Israel actually shows more concern for the lives of Palestinians than Hamas does. Every missile they launch just shores up support for the hardliners in Israel, and leaves the peace camp with nothing at all to say.

I’ll return to regularly scheduled programming very soon–just wanted to say hi, I’m back, and to share these thoughts.

October 28, 2012

What To Look For When You’re Looking For an Editor

Suppose you’ve written a novel, submitted it to literary agents and publishers, and found no takers, Chances are you’ve had little or no substantive feedback of explanation of where your work fell short. Because they receive such daunting quantities of submissions, agents usually stop reading as soon as they determine that a book is not for them. Not only do they not have time to write critiques of books they’re rejecting, in most cases they haven’t even read the whole book. The result is an enormously frustrating Catch 22 for writers. It’s difficult to get good enough to publish without smart, detailed feedback; but you don’t get that feedback until your work is sold. Writers can end up with enough rejections to paper a room and no idea of why.

At that stage, many writers pack it in. Either they shelve the book or they self-publish it in its current form, just to get it out there. Other writers double down by looking for an editor or workshop to help them hone the book before starting a new round of submissions or self-publishing. My last post, Have Red Pencil, Will Travel?, considers whether and when it makes sense to seek out professional help in the form of an edit, an evaluation, or a writing workshop.

Full disclosure: I’m a writing teacher myself, and I also do fiction evaluations and edits. I’m not drumming up business, though; in fact, I’ve put my workshops and editing work on hiatus while I work on the sequel to A DANGEROUS FICTION.

When it comes to hiring an editor, it’s buyer, beware. Anyone can call himself an editor. There are no official credentials, so it’s not like calling yourself a lawyer if you haven’t passed the bar, or a doctor if you never went to med school. Before spending money on a hired gun, better make sure he can shoot. Make sure, too, that the work you submit to the editor has already been edited to the absolute best of your ability. That will ensure that you get feedback on things you didn’t see yourself, instead of on stuff you already meant to change. This post will provide some criteria to use in choosing an editor or writing teacher. The guidelines are similar but not the same, so I’ll present them separately. First up: what to look for in an editor.

1. Substantial, verifiable experience. Ideally, the editor will have worked for a major publishing house, or written for one. Academic credentials help—a professor of English will catch your grammatical mistakes—but the most helpful editors also have a background in publishing. And don’t just take their word for it; google them.

2. Track Record. Your goal is to get published, so you want an editor who’s helped other writers get there. There are no guarantees of success, but why not choose an editor whose students have sold books to commercial publishers? Note the word “sold.” Students who self-publish don’t count as a teaching creds. Many editors have testimonials and lists of published work on their websites. If not, feel free to ask.

3. No Inflated Claims. Any editor who promises or even implies that with his help you will sell your work is either a huckster or shilling for a vanity press. No one can make that promise, and no reputable editor would. All he can reasonably claim is that the book will be better than it was, and you will learn something about writing in the process.

4. R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Look for an editor who enters into what you’re trying to accomplish, rather than imposing his own style and ideas onto the work. Editors have to be frank to be effective, but they shouldn’t run roughshod over their clients. You should come away from an edit feeling energized and enlightened, not steamrolled. Part of respect, though, is honesty. A serious critique from someone with professional standards can sting, especially at first; but if it’s too soft, you’re not getting value for money.

4. R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Look for an editor who enters into what you’re trying to accomplish, rather than imposing his own style and ideas onto the work. Editors have to be frank to be effective, but they shouldn’t run roughshod over their clients. You should come away from an edit feeling energized and enlightened, not steamrolled. Part of respect, though, is honesty. A serious critique from someone with professional standards can sting, especially at first; but if it’s too soft, you’re not getting value for money.

5. Expertise in your field. There’s no point hiring a brilliant science fiction editor if you write romance. Look for an editor who’s worked in your genre. If you’re not sure, ask.

6. Sample. Most important! Not every editor is right for every writer, and the only way to find out is to ask for a sample edit. Serious editors don’t take on every job that comes alone, so they’ll be happy to do this; they may even require it. The sample can be anything from a couple of pages to the 5000 words I read in my “Special Offer;” the cost should be nominal. Look for an editor who isn’t just making changes or correcting mechanical errors, but also teaching you something you didn’t know about writing. Send the opening pages; the feedback you get on those will be the most valuable. If you get a sample and you’re not sure the editor is right for you, keep looking.

One alternative to hiring an editor is taking a writing workshop, as rigorous as possible. Look for one that allows you to work on and share parts of your novel. In my next post, I’ll list some criteria for choosing a writing teacher. With the explosion of online classes as well as those offered in brick-and-mortar institutions, writers these days have many good options to choose from.

If you find these posts useful, you might want to sign up for the URL feed or subscribe via email. And now I’ll say goodbye for a little while. I’m going on vacation, and will be back posting on the weekend of November 17. But I’ll check in for comments, and would love to hear your thoughts about and experience in working with an editor.

October 21, 2012

Have red pencil; will travel?

Should writers hire freelance editors? It’s a vexed question, much debated on the writers’ forums and blogs. My own opinion has evolved over time with the changes in the publishing industry, and it may surprise those of you who know that I myself have worked as a fiction editor. My default position is that they should not… or at least, not right away.

Whenever this question is discussed on other blogs and forums, invariably someone will say, “It’s the writer’s responsibility to edit his own work. It’s part of the job,” to which I say, Amen. First drafts are not finished novels, and shouldn’t be regarded or presented as such. They are the imagination’s playground: rough, and meant to be. Revising is where the real art comes in. That’s where writers deepen their characters, vet the structure of the book, deal with unruly subplots, refine the language and imagery, and find ways to bring out the theme, which often presents itself to the writer only after the first draft is written. “Every writer,” Jane Smiley wrote, “has to learn to…come at each piece of work again and again with as close as he can get to a new mind and a new sense of joy.” Rome wasn’t built in a day, and novels are not written in one pass. Most of the published writers I’ve known spend at least as much time revising as they to writing the original draft. ”I am an obsessive rewriter,” Gore Vidal once said, “doing one draft and then another and another, usually five. In a way, I have nothing to say but a great deal to add.”

Nevertheless, writers need editors. As writers we can only see what we see; we don’t see what we can’t see. It sounds simplistic but it’s true. Every artist gains through smart, objective feedback. Beta readers can be helpful if the writer chooses well and gets lucky, but it’s not at all like feedback from a professional editor with professional standards. A good editor knows not only when something isn’t working, but also why and how to fix it. The result is a better book, and that, I believe, is what every true writer wants most for his work. The process is also educational, since learning from smart editing is one of the primary ways in which writers grow. What they absorb through the editing of one book, they will apply to the writing of the next one.

Why, then, if editors are so essential, do I advise writers against hiring their own? For purely financial reasons. If the book sells, it will be edited at the publisher’s expense. Edits are not forced down the throat of writers, by the way, contrary to propaganda put out by some self-publishing advocates. Edits usually come in the form of questions or suggestions. The final word is always with the writer, although in extremely rare cases, when communication between writer and editor totally breaks down, a publishing house does have the right to withdraw from a contract if the book is not, in their view, publishable. (The reason such occurrences are rare is because publishers don’t usually buy books that need tremendous amounts of work unless they’re by celebrities, and in those cases there is usually a professional ghostwriter attached.) Paying out of pocket for the same level of editing would be exorbitantly expensive. First-rate, experienced editors charge a lot; $10 and upwards per page is common, and that is just for the first edit. To duplicate the services provided by trade publishers, you’d also have to pay for an edit of the revision, as well as copy-editing and proofreading: maybe $18, $20 a page. (Let me anticipate objections by conceding that yes, you can hire editors for less; but as is usually the case, you get what you pay for.) That’s a lot of money to invest in a book that may never sell. And the sad truth is that the vast majority of first novels, edited or not, do not sell.

That’s why I recommend that when writers have finished a novel (by which I mean they’ve edited it thoroughly, shared it with a trusted beta reader or two, and revised again to implement whatever useful feedback they receive), they send it out to test it in the market. Of course, to give the book a fair chance, writers have to bone up on submission protocol, write a great query letter, and assemble a list of suitable literary agents. Having done all that, it’s time to let the book go forth and seek its fortune in the wide world. If it attracts an agent who then sells it to a publisher, the publisher will provide editing services at no cost to the writer. That’s a big part of what they do, along with production and marketing.

But such a scenario is the best of all possible worlds. Suppose it doesn’t go that way? What if you’ve written a novel, sent it out, and gotten nothing but form rejections from agents: no encouragement, no criticism, no feedback at all. It happens. Agents stop reading the moment they determine that a book is not for them; they don’t finish the ms. and write thoughtful critiques. Writers can accumulate a stack of rejections without an inkling as to what went wrong and how to fix it. Or they might come close—requests for full mss. from agents, even an offer of representation followed by no sale. What do they do then?

But such a scenario is the best of all possible worlds. Suppose it doesn’t go that way? What if you’ve written a novel, sent it out, and gotten nothing but form rejections from agents: no encouragement, no criticism, no feedback at all. It happens. Agents stop reading the moment they determine that a book is not for them; they don’t finish the ms. and write thoughtful critiques. Writers can accumulate a stack of rejections without an inkling as to what went wrong and how to fix it. Or they might come close—requests for full mss. from agents, even an offer of representation followed by no sale. What do they do then?

Once, for lack of any other alternative, these unwanted works would have been shelved, mourned over, and eventually forgotten. These days, writers have choices. They fall into four categories:

Option 1. Writer decides that agents are bums and stink at their jobs; tells himself that no one gets published without knowing someone in publishing; concludes that the game is rigged; and, rather than deprive the world of his work and himself of the glory, decided to self-publish. None of these suppositions, by the way, is true. Celebrity authors aside, publishing is one of the few remaining meritocracies. In the past year alone I’ve had the pleasure of seeing four of my Next Level students sell their first novels, and none of them had any connections or “platform.” (If you want to learn how they did it, two of them, Tiffany Allee and Mika Ashley Hollinger, answer that question in interviews on this blog.) Writers who choose to self-publish are well-advised to hire an editor, and not just any editor but the best one they can find and afford. Sending a book out into this market without editing is like dropping a toddler off to play in Times Square; it will be squashed flat in no time at all. It makes economic sense, too, to invest in editing. In a recent study of self-published books by the Taleist magazine, researchers found that edited fiction outsells unedited fiction by a wide margin.

The advent of inexpensive self-publishing and the rise of the ebook has given writers options they never had before. I do think self-publishing is a very difficult road, especially the marketing aspect. In the U.S., over 300,000 books were self-published in the last year, and they are all competing furiously for attention, reviews, sales. But that’s a whole other topic, and if you want to hear my take on it, you’ll find it in a post called “What If J.K. Rowing Had Self-Published?” My point here is that having choices is a beautiful thing. Over the years I have read some brilliant early novels by writers who didn’t have instant commercial success. Maybe they get to publish a second novel, maybe not; but an awful lot of wonderful writers disappear from the market because their sales figures killed them in the eyes of the increasingly monolithic (and well-informed) publishing industry. Who knows what they might have written had they been able to continue? Today such writers have other ways to find readers, and readers to find them.

The advent of inexpensive self-publishing and the rise of the ebook has given writers options they never had before. I do think self-publishing is a very difficult road, especially the marketing aspect. In the U.S., over 300,000 books were self-published in the last year, and they are all competing furiously for attention, reviews, sales. But that’s a whole other topic, and if you want to hear my take on it, you’ll find it in a post called “What If J.K. Rowing Had Self-Published?” My point here is that having choices is a beautiful thing. Over the years I have read some brilliant early novels by writers who didn’t have instant commercial success. Maybe they get to publish a second novel, maybe not; but an awful lot of wonderful writers disappear from the market because their sales figures killed them in the eyes of the increasingly monolithic (and well-informed) publishing industry. Who knows what they might have written had they been able to continue? Today such writers have other ways to find readers, and readers to find them.

Option 2. Writer concludes that the book is not good enough yet and goes back at it again. In this case, it makes sense for the writer to consider hiring an editor to provide skilled, objective feedback. It’s also possible to find professionals who will do detailed evaluations of the book or part of it, pointing out the strengths and weaknesses of the work in a very specific way without actually doing the edit for the writer. Evaluations are usually much less expensive and possibly more educational, because the writer has to do more of the actual work of revision, rather than having it done for him. It must be said that making this investment of time and money does not assure publication. It will result in a better book, but whether it’s publishable or not depends not just on the quality of editing but the quality of the original material. What the edit is bound to do, I think, is teach the writer a lot about the craft. I see it as an intense, detailed tutorial that focuses on the writer’s own work; and given the uncertainty of publication, this may be its greatest value.

Option 3. Writer gives up on that book and goes on to the next, building on what he learned from writing the first. Most published writers have an early unpublished work or two in their drawers. (For current and future generations of writers, that may become “an early self-published work or two.”) One novelist I knew—Ted Whittemore, author of the brilliant Jerusalem Quartet—wrote seven books before selling his “first” novel.

Option 4. Writer gives up on writing and takes up another pursuit. It happens, and not necessarily for lack of talent. To succeed in this tough business, people need also need fanatical perseverance. (As Richard Bach said, “A professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit.”) They need another source of income, too, since only a small fraction of writers support themselves through books alone. And let’s not forget the luck factor, lest it forget us.

Writers who choose Options 1 or 2 might also consider as an alternative to editing putting their books, and themselves, through a rigorous writing workshop that will allow them to work specifically on their novels. There are quite a few available, both in brick-and-mortar institutions and online. In my opinion, if a first round of submissions has not led to a sale, it’s worth delaying a second round, or self-publishing, in order to do your very best to improve the book in hand.

Writers who choose Options 1 or 2 might also consider as an alternative to editing putting their books, and themselves, through a rigorous writing workshop that will allow them to work specifically on their novels. There are quite a few available, both in brick-and-mortar institutions and online. In my opinion, if a first round of submissions has not led to a sale, it’s worth delaying a second round, or self-publishing, in order to do your very best to improve the book in hand.

Whether you choose a course, an editor, or an evaluator, it’s essential to do your homework and find someone who’s both well-qualified and suited to your particular project. In my next post, I’ll set out a list of criteria for writers to consider before making that choice.

October 11, 2012

Book Jackets

Yesterday I saw Viking’s jacket for A DANGEROUS FICTION, and I am over the moon. I think it’s stunning visually, and it perfectly captures both the book and its protagonist in a single image. Kudos to Viking’s wonderful team: my editor, Tara Singh, in-house designer, Alison Forner, and the artist Malika Favre, whose website is a small marvel. The book won’t be out until July 2013, but it feels very real now. Here is the cover:

What do you think? Would you pick it up if you saw it in a bookstore?

In a way, I’m like my grandmother Pauline. Every time Pauline was presented with a new grandchild or great-grandchild, she would exclaim that this is the most beautiful baby ever born. I’ve loved nearly all the jackets to my books. But I really do think this one is the most beautiful of all.

In publishing, cover art is the purview of marketing, which means that publishers, not writers, have the final say. Agents write cover approval into contracts, but vetoing a cover is a big deal and can lead to postponement of publication, an even bigger deal. So that right is rarely exercised.

Fortunately for me, I had some wonderful artists and designers for my covers. Having little or no visual imagination myself, I was delighted to have professional help; the jackets usually came as very pleasant surprises. The only one I ever found for myself was this painting by Israeli artist, which graces the cover of my novel CAFÉ NEVO.

Only once did I have a problem with the cover art for a novel, and in fact that was sort of a proxy dispute over the marketing of the book. I saw SAVING GRACE as a novel about corruption and the intersection of politics and family. My publisher saw it as a “women’s fiction.” Here are the covers, hard and soft, that they came up with.

Not bad looking, especially the paperback, but the main problem was that they didn’t fit my concept of the book. They looked girly to me, an impression solidified by a letter that I got from one male reader, who said that he enjoyed the book greatly but had to take the jacket off before reading it on the subway. Men, we can sigh, but they are what they are and I’ve always wanted to attract readers of both sexes.

Viking’s cover for A DANGEROUS FICTION may also skew to women readers, though maybe not; I’d love to hear your thoughts on that point. But apart from being a thing of beauty in itself, this cover suits the book perfectly, and that makes me very happy.

Have you ever thought about what attracts you to a book jacket? If you didn’t already know the writer, what makes you stop and pick up a book?