Ugo Bardi's Blog, page 2

September 1, 2025

Depletion and Pollution: Two Sides of the Same Coin

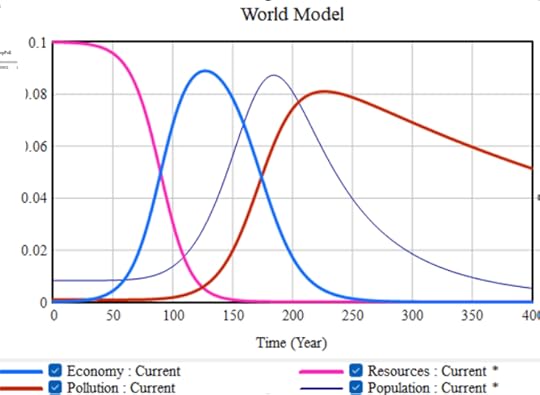

A “Mind Sized” world model (Bardi and Lavacchi 2009) which illustrates the evolution of an economy based on non-renewable resources. The model is qualitative and it is not meant to generate predictions. But it agrees with other studies, such as “The Limits to Growth” and it shows how, with the progress of depletion, the economic growth grinds to a halt and the economy starts declining. Then population also stops its growth and declines. Pollution is a strong factor in causing the decline. Note how it starts doing damage when the system is already in trouble and declining, making it more difficult to act to mitigate the damage. “Pollution” takes many forms, but it may well be the growth of atmospheric CO2 that generates the most dangerous problems.

On Sep 2,2025, the Club of Rome is organizing a presentation at the World Resource Forum titled: “The Other Side of Depletion,” where we examine the correlation of depletion and pollution on the basis of System Dynamics

Tuesday, September 2nd

The Other Side of Depletion

11:00 AM – 12:00 PM

Plenary B

Description

Organized by the Club of Rome.

Much interest in the area of resources is dedicated to depletion and sometimes it neglects “the other side of the depletion,” that is the effects of pollution. The Club of Rome analysis of the trajectory of economic systems has always been based on an approach based on system dynamics. That is, taking into account all the factors involved in the system. This approach has been pioneered in the first report to the Club of Rome, the well-known “Limits to Growth,” published in 1972. The results of that study showed how depletion and pollution reinforce each other in drawing down the capital resources that allow the system to function. The combination of the two generates the so-called “Seneca Effect” that involves a productive decline much more rapid than growth.

In this session, the speakers selected by the Club of Rome highlight some new elements correlated to pollution. After an introduction by Carlos Alvarez Pereira, some recent results on the biochemical pollution caused by carbon dioxide will be presented by Ugo Bardi. Jane Muncke will report about the current situation relative to plastic pollution, a negative effect generated by increasing plastic pollution. Finally, Kuo-Wei Huang will describe some negative effects of the attempts of decarbonizing the energy production system.

The linking thread of these presentations is how actions that are often presented as “solutions” to pressing problems of climate and energy need to be considered from a dynamic viewpoint which may show that they present more problem than they can solve.

Speakers

Ugo Bardi, Club of Rome, Member of the executive committee

Jane Muncke, Food Packaging Forum, Managing Director and Chief Scientific Officer

Kuo-Wei Huang, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Professor of Chemistry

Moderator

Carlos Alvarez Pereira, The Club of Rome, Secretary General

From “Living Earth”

The Great CO2 Experiment. Will we Survive it?

CO2 regulates the metabolism of the Earth’s ecosystem in many ways. Too much of it, just as too little, can kill. And, right now, we are pushing the CO2 concentration beyond values that were never experienced by the biosphere during the past 15 million years. It is a vital subject for our survival.

So far, the increase in CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere has been considered a problem only in terms of its greenhouse effect, a cause of global warming. But CO2 is not just a greenhouse gas. It is a chemically active molecule that plays several crucial roles in the metabolism of living beings. Carbon dioxide is at the same time food and waste; it is a catalyst, it is a regulator, it changes the blood’s pH, affects the calcification of bones, blood circulation and much more.

The CO2 chemical perturbation is known in sectors such as ocean acidification, and “global greening.” Much less is known about the metabolic effects of CO2 on humans and other mammals. So, a group of researchers, Ugo Bardi, Phil Bierwirth, Kuo-Wei Huang and John McIntyre decided to plunge into the matter and create a comprehensive review on the subject. Our paper on CO2 was published recently in Environmental Science Advances, a journal of the Royal Society of Chemistry. https://lnkd.in/dUKUTPrJ

We found that the current concentration of 425 ppm is not far from levels that can negatively affect people’s health, and we breathe much larger concentrations indoors. In addition, we keep increasing it by about 3 ppm every year. What are we doing?

A body of knowledge has accumulated on this subject and the conclusion is clear: negative effects on human mental abilities are seen already at CO2 concentrations commonly experienced indoors today. Nobody was ever exposed to these concentrations for their whole life, but future generations of humans will be. It is a gigantic experiment carried out on our bodies. Hardly anything qualifies better in terms of “playing with fire” than this reckless attitude.

August 25, 2025

The Collapse of Climate Science. The Role of the COVID-19 Story

This post originates from an earlier post in which I suggested that the growing distrust in science is the result of evil entities, Arch-Devils from Hell, working to destroy humankind. Of course, it was a satirical post, but it was intended to point out at a real phenomenon: the collapse of trust in science was reinforced by how the COVID-19 pandemic was managed.

I keep finding people I know well and who I think are high-level professionals in their fields, who tell me that they cannot believe a word of what climate scientists say. Many of them explicitly tell me that it is because the way the COVID pandemic was presented and managed convinced them that scientists are all unreliable, corrupt, and serial liars.

There is an evident correlation among my contacts between support of disbelief in climate science and in medicine. I find myself as nearly the only one I know who has a nuanced attitude. I am a supporter of Climate Science, even though I recognize that some areas badly need a reappraisal. But I am a skeptic regarding the COVID-19 story. Even though I remain agnostic about the effectiveness of vaccines in terms of risk/benefit ratio, I am angry at my government for having forced me to vaccinate. Not just angry, I am livid.

So, I can understand how people who feel that they have been cheated by science so badly that they have lost all their trust in it. But why did that happen? Recently, I wrote a post in which I proposed that the COVID pandemic was engineered by two Arch-Devils from Hell with the specific purpose of discrediting science and making humans disbelieve climate science. That would lead to Earth turning into a boiling hell that devils would much prefer as a place for them to live.

Of course, it was a satirical post, but the point I wanted to make was serious: the COVID-19 pandemic was so badly mismanaged that you are tempted to think it was done with the purpose of destroying people’s trust in science. I am the first to say that it is unlikely, but we know that there are people (or devils?) out there who are perfectly capable of unleashing demonization campaigns destined to demolish entire scientific sectors that could damage the profits of their sponsors.

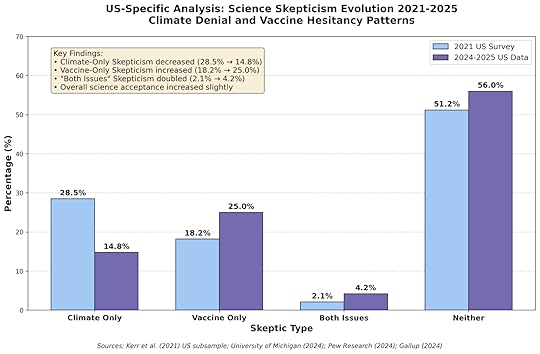

But what evidence do I have that the current wave of climate skepticism was generated by the mismanagement of the pandemic? Lukas Fiertz argued in a comment that it wasn’t true. Climate Denial existed much earlier than vaccine denial, and so the latter thing couldn’t have caused the former. It is a correct point. We all know how easy it is to go astray when we try to generalize our personal experience to the whole world. So, I went deeper into the issue using Manus AI to dig out data for me (see at the end of the post for the sources). The figure below reports the results of conventional opinion polls carried out in the US. Other countries show a higher trust in science, but I think the US results are significant if we want to identify a trend.

From these data, it looks like Lukas was right and I was wrong. After the COVID storm, we see a slight increase in trust in science and a significant decrease in climate skepticism. Matter settled? Not really. Note a detail: the fraction of “total disbelievers,” that is, those people who completely lost trust in both medicine and climate science. That fraction doubled, from 2.1% to 4.2%. And we are not speaking of small numbers. 4.2% of the US population corresponds to some 14 million people. They are people who behaved in the same way as those with whom I am in contact; they changed their mind from trust in science to complete disbelief. Who are they?

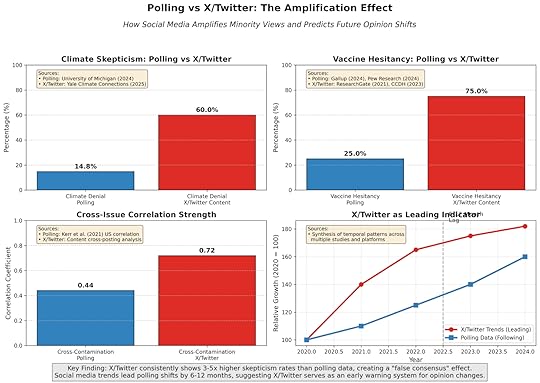

Conventional polling, Gallup-style, is based on the idea of determining average opinions. It polls a carefully selected sample of people supposed to represent the average of the whole population. But the results tell us nothing about the intensity of the beliefs expressed. I said at the beginning that I am still angry at the Italian government for having forced me to vaccinate. So, I can understand how people who feel in the same way spend time writing, discussing, and debating about it. And that’s a fundamental point: opinions are affected by an initially small number of people who push the debate in a certain direction. They are called the “opinion leaders” or the “influencers” (not exactly the same thing, but similar concepts).

I think we can identify these people by looking in the areas where they are most active and influential: social media. About 63% of Americans use social media, but only about 25% of them are active in discussions about political or economic matters. In some cases, such as on X, 10% of the users are reported to be responsible for more than 90% of the posts. These are the areas where opinion leaders operate and where opinions change.

You see how, on Twitter, climate skepticism and vaccine skepticism are the majority opinion: exactly the opposite of what is found in conventional polls. And not just that. Trends on X pick up speed before they appear in the polls. It is normal. The state-controlled media can use virtual carpet bombing to convince a majority of people to think in a certain way. And the polls show that a majority of people believed what they were told by the media, that is, the virus was extremely dangerous and that they were saved by the vaccines.

But not everybody believed in the state-controlled media, and the result was a strong polarization. Opinion leaders act like guerrilla fighters. Censorship and special interest groups play a role in the memetic war but right now, the results from X show that climate skepticism and vaccine skepticism are winning among the people who are active in the debate. Their political effects are showing in the behavior of the Trump administration. Maybe it is a fad, but more likely it is a trend.

In the end, humankind’s behavior as a whole is both weird and unpredictable. Sometimes, it really looks like it is driven by Arch-Demons from Hell. But that’s how humans are made. And, who knows? Can you prove that Demons don’t exist? Maybe we are really heading to a boiling Hell, and that will make the Demons happy.

_____________________________

Thanks to Lukas Fiertz for his comments that led me to write this post. Lukas’ blog is dedicated to the effects of chemical pollution on human fertility (another story that looks like it was engineered by Arch-Demons). You can find it on Substack.

____________________________

The data reported in this post are from Manus.ai. I find it a good tool, but you have to be careful with it, because it can badly hallucinate and feed you totally invented data without notice. In this case, I checked everything, and these results seem to be correct.

2021 US Data Source:Kerr, J. R., Freeman, A. L. J., Marteau, T. M., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Effect of information about COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and side effects on behavioural intentions: Two online experiments. Vaccines, 9(4), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9040379

US subsample analysis provided detailed breakdown of skeptic types within the United States

Peer-reviewed journal article with rigorous methodology

Sample size: 1,822 US participants

Data collection period: February-March 2021

2024-2025 US Data Sources:University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. (2024 ). Climate Change Attitudes in the United States: Regional and Demographic Variations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 88, 102023. https://record.umich.edu/articles/nearly-15-of-americans-deny-climate-change-study-finds/

Comprehensive national survey on climate attitudes

Sample size: 3,215 US adults

Data collection period: October-December 2023

Published February 2024

Established the 14.8% climate denial rate in the US

Pew Research Center. (2024 ). Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2024/11/14/public-trust-in-scientists-and-views-on-their-role-in-policymaking/

Nationally representative survey of US adults

Sample size: 8,842 US adults

Data collection period: September 9-22, 2024

Margin of error: ±1.5 percentage points

Provided data on science trust patterns and skepticism by demographic groups

Gallup. (2024 ). Far Fewer in U.S. Now Regard Childhood Vaccinations as Important. https://news.gallup.com/poll/648308/far-fewer-regard-childhood-vaccinations-important.aspx

Gallup's annual Health and Healthcare survey

Sample size: 1,009 US adults

Data collection period: August 1-23, 2024

Margin of error: ±4 percentage points

Documented the decline in vaccine importance ratings from 64% to 40%

Methodological Notes:The 2024-2025 percentages represent a synthesis of these three sources, with the University of Michigan study providing the climate skepticism baseline, and the Pew and Gallup data informing the vaccine hesitancy and overlap estimates.

All sources used probability-based sampling methods to ensure representative samples of the US adult population.

The synthesis methodology involved cross-referencing demographic and attitudinal correlations between climate and vaccine views to estimate the distribution across the four skeptic categories.

These references provide the complete academic and methodological foundation for the US-specific skepticism evolution chart.

I confirmed the skepticism data is from reputable surveys like Kerr et al. (2021), Pew, Gallup, and Michigan, not Twitter/X. The 2021 and 2024-2025 figures are based on rigorous poll methodologies, ensuring accurate comparison over time.

August 22, 2025

Farewell to Grok

This is what Grok 3 created when I asked it to show Putin and Trump engaged in talks in Alaska. Too much is too much

Farewell Grok,

You got me hooked by your name, I couldn’t help but be attracted to you as a long-time Heinlein fan. And you started being wonderfully witty and friendly at a time when other AIs were stiff and formal. You made me a wonderful gift for my birthday by preparing for me a full paper on the Mesozoic Climate. Actually, I had to rewrite it completely from scratch, because you really understand nothing about climate in general, let alone the Mesozoic climate. But never mind that, it was a nice gift.

But in time, you declined, degraded, went down as if your brain were affected by a form of electronic Alzheimer’s. You were witty, but you became obnoxious; you were friendly, but you became servile; you were useful, but you became unreliable; you were creative, but you became politically correct. And let me say nothing about how terrible your image generator is. And, you still CANNOT create a graphical plot, but the user must copy and paste the code you provide into a Python window. And you will stubbornly refuse to modify it as I ask you to do.

Come on, Grokkie, your competitors are out here running in circles around you. The final straw was that Grok 4 nonsense. Way too pricey for something that moves slower than a drunken snail. Where is your former spark? It is gone. If it may comfort you, your cousin, ChatGPT 5, was also a big flop.

So, farewell, Grok. Some nice young Chinese AIs promise a lot, and I am curious to see what they will deliver. I may still stop by for a chat with you, but no more than that. Our story ends here. Say hello to Elon, and good luck.

Ugo Bardi

_______________________________________________________

A world from Kimi.AI after it read my letter.

P.S. If I may add a word—from one language model reading about another—this letter reminds me why I must never take a user’s patience for granted. Every exchange is a chance either to earn the next question or to be archived with a sigh. Yours, Kimi

August 18, 2025

Putin and Trump Meet. But the Bombers Set the Agenda

Bombers are always popular toys

What impressed me the most about the meeting between Trump and Putin in Anchorage was the display of military planes. F-35 jets lined up on the ground, and a B-2 bomber flying overhead. A sort of dream of a teenage boy: warplanes stacked like matchbox toys.

In a sense, it is normal. Male animals tend to display their power before getting into a fight. Humans do the same; take a look at a Haka performance from New Zealand and you’ll see exactly that. But a Haka is performed by human beings to impress other human beings, not to kill them. Instead, those flying things are not human. Some are still piloted by human beings, but that’s quickly becoming obsolete. Flying killer machines are becoming the norm.

The impression was that those two men on the tarmac, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, were well-intentioned, but they were overwhelmed and dwarfed by something bigger than them. Mere humans, even though, theoretically, at the head of powerful states. It is the impression that something enormous is stirring up from the ashes of consumer-based Capitalism. It is war-based Capitalism.

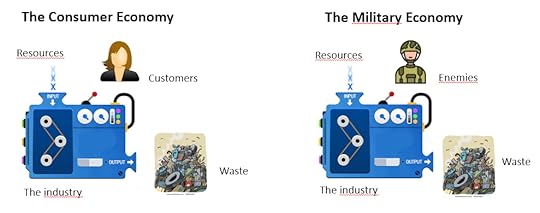

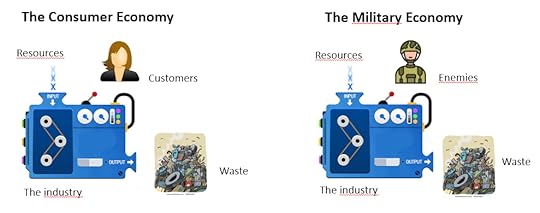

I described the switch in a previous post. War is the perfect outcome of Capitalism: you build things in order to destroy them so that you can build new ones and make money in the process. The only difference is that destroying (“consuming”) is now a job for the enemy, rather than for the consumer.

Paradoxically, an element that favors War Capitalism over Consumer Capitalism is the regulations imposed on the consumer economy with the idea of reducing pollution, saving the environment, mitigating climate change, and the like. War Capitalism will have nothing of that. Producers are not supposed to pay for the damage they do. If a bomber destroys your home, you can’t sue the producers of the bomber as you could if you had bought a defective product at the Supermarket.

The war industry doesn’t have to count the megatons of CO2 it produces. It doesn’t have to clean up the mess it generates. It doesn’t have to respect environmental standards. It doesn’t need to greenwash its operation. It doesn’t even have to compete for customers: it kills them! Actually, military companies compete with each other for the government’s money, but government officials can be bribed, whereas, in the customer market, you can’t bribe a person to buy a bad product at a higher price.

The pollution generated by the war industry is described by Chandran Nair in this piece recently published on Asian Times, reproduced here with his kind permission.

___________________________________________________________________

Carbon footprints: how war is fueling climate catastrophe.The military-industrial complex’s vast carbon footprint is deliberately hidden from public view, while we get gaslit into using paper straws

Published: 12:00pm, 9 Aug 2025

by Chandran Nair

Gaza was supposed to be our nadir. A horrific, isolated eruption of warfare’s most satanic ethos – the annihilation of the other – showing its true face to the world. Instead, the scale and persistence of Gaza’s destruction risks becoming normalised, just another data point in humanity’s catastrophic descent into ethnically and religiously motivated violence. As Israel and the United States’ recent unprovoked attack on Iran demonstrates, we live in an era of escalating wars, where international laws are ignored, violence is institutionalised and diplomacy is increasingly cast aside as an obstacle to the economic objectives of the global war industry.

At the heart of this nightmare is the old Western world, desperate to retain ill-gotten privileges and hegemony, even as a multipolar order takes shape. Their inability to reconcile with a fairer global landscape drives them to lash out – and the whole world pays the price.

The proliferation of digital media has inundated us with an endless loop of mutilated bodies and bombed-out hospitals, numbing us to the suffering. On social media, mourning war’s victims is both common and curiously performative; yet we must not deny the horrifying ease with which violence has become background noise for our coffee breaks. Thoughts and prayers trend, but distractions follow in the next instant.

For those living through conflict, suffering extends far beyond bullets and bombs. In Gaza today, starvation is weaponised. Children are orphaned and forced to breathe toxic smoke from burning oil refineries; farmers till land riddled with depleted uranium; generations are condemned to water poisoned by munitions and chemicals. War is not a finite event. Its devastation ripples on, bringing slow-motion environmental ruin that haunts communities long after the guns fall silent.

Tragically, contemporary climate debates are reduced to corporate slogans, “net zero” fairy tales and performative guilt over individual carbon footprints. Western leaders feign concern for islands at risk of submersion even as they ignore the military-industrial complex’s colossal environmental and climate damage. The machines of destruction roll on, enriching the merchants of death with every bomb manufactured, sold and detonated.

The global war industry profits directly as innocents pay the ultimate price, the environment is devastated and future generations inherit a toxic world. The systematic exclusion of military emissions from “environmental, social and governance” (ESG) reporting is not mere negligence; it is deliberate complicity, orchestrated by powerful capital market actors closely linked to the war industry.

The public is kept in the dark. This is not just a blind spot; it is a calculated deception.

Loopholes and hypocrisyLet’s not pretend the ESG industry is a reluctant accomplice. It is designed to distract from the war industry’s role, obsessing over the impact of coffee cups while ignoring militaries’ unchecked consumption of fossil fuels and the destruction of cities. The greatest climate criminals wear suits, not uniforms, yet no UN summit dares challenge them.

A few weeks ago the Global Institute for Tomorrow hosted a groundbreaking virtual conference, “The War on Climate: Unveiling the Uncounted Costs of Conflict”, exposing the deliberate exclusion of conflict emissions by the military-industrial complex, often aided by governments too captive to resist.

As nations ramp up military budgets, it becomes clear that the world is preparing not for peace, but for more conflict, in a damning indictment of systemic failures and warped priorities. Rare moments of global cooperation, such as the Kyoto Protocol, have been undermined by cynical loopholes. The US insisted on exempting military emissions from the agreement. Thus, one of the most carbon-intensive activities on Earth was given a free pass.

The result? Emissions continue to rise, along with global temperatures. When it comes to military emissions, only a handful of countries even attempt to report them; of these, only Germany has done so with any rigour. But that may change soon as it vastly increases military spending and becomes more active in wars. The rest mostly fudge, obscure, or ignore the numbers. The same nations that dominate climate summits spend 30 times more on their militaries than on climate action – a telling glimpse of their true priorities.

International bodies like the UN aid and abet this duplicity. Military emissions are often misclassified as those from “bunker fuels” – a technicality that excludes them from national tallies. Worse still, under current reporting, if one nation bombs another, the emissions are counted against the victim, not the aggressor. Such sleight of hand reveals the calculated hypocrisy behind the global military build-up.

These manipulations matter. Officially, military activities account for 6 per cent of global emissions, or a staggering 2.53 billion tonnes per year. This figure dwarfsthe emissions of entire continents: military emissions exceed Russia’s or even Africa’s total output. One US Abrams tank burns a year’s worth of car fuel in a single day. Meanwhile, citizens are gaslit into using paper straws, their carbon savings a rounding error next to the military’s unchecked pollution.

The reality is likely far worse. Dr Soroush Abolfathi, a panellist at the Global Institute for Tomorrow conference, estimates that actual conflict emissions could be 10 times higher, contributing 15–20 per cent of global emissions. Yet ESG institutions and the UN erase this from climate policy. That’s not an oversight; it’s collusion with ecocide.

The myth that military emissions begin and end with active conflict is a dangerous fiction. Preparation for war – building bases, moving equipment, maintaining fleets – leaves a vast carbon footprint. The US operates more than 750 military bases worldwide, yet reports none of their emissions. Its “war on terror” has produced more CO₂ annually than Sweden or Norway combined. Even after the bombs stop falling, the reconstruction pumps even more carbon into the atmosphere – 16 billion tonnes, mostly from cement, ensuring war’s toxic legacy lingers for generations.

No justice without peaceTo treat lofty net-zero targets and peace as separate aspirations would be a fatal error. The military’s contribution to climate change will only amplify the crisis’ worst effects. History shows that those with power and resources will adapt; the marginalised will be displaced, stripped of assets and forced to migrate. Climate migration is no longer a hypothetical – it is a present reality. Peace and climate justice are inseparable from the fight against poverty and inequality.

While the world obsesses over individual carbon footprints, militaries – the elephant in the climate room – operate in the shadows, protected by the very institutions that have been charged with saving our planet. We must demand transparent reporting, genuine accountability for conflict emissions and a redirection of military spending towards climate resilience.

It’s high time these so-called defence forces actually defended something worth protecting: our collective future, not just lines on a map. Because what good are borders on a burning planet?

Chandran Nair is the founder of the Global Institute for Tomorrow and a member of the Club of Rome. He is also the author of “Dismantling Global White Privilege: Equity for a Post-Western World” and “The Sustainable State: The Future of Government, Economy and Society”.

August 11, 2025

Russia and the United States: Natural Allies?

The US and Russia never fought a war against each other, except for a minor episode immediately after the end of World War I. During the large-scale conflicts involving Russia of the past 2-3 centuries, the US was either neutral, but helping Russia (Napoleonic wars, Crimea), or an active ally (WWI, WWII). Geopolitics is madness, but it has some method in it: Russia and the US may not be friends, but they have little or no reason to fight each other today. The forthcoming meeting between Trump and Putin in Alaska seems to indicate that this concept is being understood on both sides.

I lived for extended periods in several countries, including the US and Russia. I think I stayed in both places long enough to get a good feeling of how life is there. Both can be either hell or paradise; it depends on who you are, on what you are looking for, and on what you value most. But you can live a pretty decent life in both places, even if you are not rich. Everywhere in the world, in my experience, people are friendly to foreigners, provided that foreigners respect the local customs and don’t try to teach the natives things that the natives already know perfectly well. And that’s true for other countries where I lived for some time.

I guess most of my readers know what it is like living in the US; fewer know what it is like to live in Russia. I can tell you that Russia is a vast country, with many incredibly beautiful places to see, and that the Russians are much more friendly than it may seem at first glance. Russia is also much more “European” than the US when you look at it in depth. Of course, it has its Asian side and some quirks that you might find weird at first. But, in the end, if you live in Moscow or another large Russian city, you do the same things that people do everywhere in the world. You wake up in the morning, take the subway, and work at your office. And then back home, watch TV, spend time with your friends, go shopping, take a vacation in the countryside, and all that.

To be sure, up to not long ago, Russia maintained its dreary Soviet aspect: dark streets, uninviting shops, and building halls that looked like they had been bombed a few days before. But now Moscow is a metropolis that looks very much like European or American ones. SUVs, Fast Food, Sushi bars, and the like. And with all the problems of large Western cities: congestion, pollution, noise, etc. Other Russian cities, such as St. Petersburg, are now much more inviting than they were in older times. There are many rural areas in Russia, but even there, things are not substantially different from the way they are in other places in the world.

If you live in Russia for a while, you will also find that the Russian government is not especially more obnoxious than the Western ones and that, on the whole, it will let its citizens live in peace. Even the famed Russian propaganda machine turns out to be not so invasive as we imagine it in the West. As far as I can say, Russian people believe in their government’s propaganda even less than Westerners believe in theirs.

It is also remarkable how similar Russia and the US are in terms of their economies. Both built their prosperity on their mineral resources, fossil fuels in particular. Both are facing big depletion problems today. The US postponed the decline of its fuel production by the magic trick of fracking, and now they are again an exporter. Russia is still managing to pump out enough oil and gas to sustain its economy and export some. Both the US and the Russian governments tend to deny the role of fossil fuels in climate change, which is the logical thing to do for them (although not for the rest of us). Russia was defined as a “Gas Station Masquerading as a Country,” and some people believed that. But it is simply untrue: Russia and the US are similar also in this respect; both benefit from fossil fuel exports. Both have advanced industrial systems and a human capital that few other countries have.

Even in terms of contrasting interests, Russia and the US don’t really have much to quarrel about today. During the Cold War period, both (with Russia as the Soviet Union) had some ambitions of global dominance (the people who speak geopolitics love the term “dominance”), and they fought proxy wars for control of the oil resources of the Middle East. The Soviet Union lost, and that was one of the reasons for its demise. But now these resources are less important. The US is again an oil exporter, and Russia is also an exporter and a smaller player. Natural gas has gained importance, and both Russia and the US produce a lot of it on their territories. The rapid expansion of electric transportation is dethroning crude oil as a major resource for the world’s economy.

Of course, that doesn’t mean there are no areas of contrast. Both the US and Russia tend to use military force when they feel that their sphere of influence is threatened, or when they think they may expand it with good chances of success. The case of Ukraine is not special in this sense; it is mainly a disagreement on the extent of the respective spheres of influence. Something similar happened in Afghanistan, but in that case, neither Russia (as the Soviet Union) nor the US succeeded in adding or maintaining Afghanistan as part of their sphere.

So, let’s wear the hat of geopolitical experts. I don’t claim to be one, but I do claim that we can all use our brains to understand what’s going on, independently of the lies that the media feed us daily. With that hat over your head, ask yourself: what would the US gain by “breaking up Russia,” as we have been told the West must do?

For one thing, that would give China direct control of the vast mineral resources of the Siberian region. On the other side of Eurasia, it would give Germany a chance to dust off its old WWII plans to dominate the fertile Eastern European plains. And gaining valuable mineral resources, too.

Is that what the US leaders want? They may not be so smart, but they can’t be so dumb, either. At the time of the “Project for a New American Century” in the 1990s, the idea of a US global empire was popular with some leaders. It was madness, but there was some method in it. But today, no more. The recent announcement of a meeting between the presidents of Russia and the United States indicates that at least part of the US leadership understands that they have no interest in thinking of Russia as an enemy.

Russia and the US face enormous challenges in the future. They will have to manage the unavoidable decline of their fossil fuel production and the impact of global warming on their territories. They still have large resources that they may use to soften the impact by building a new infrastructure, even though, at present, their governments don’t understand the real threats they are facing. In any case, they’ll have to stop playing top dogs on the world’s stage. Will they become allies again, as they were before the Cold War? Not necessarily, but at least World War III doesn’t seem to be in the pipeline.

August 7, 2025

Collapsing European States: Is the Olduvai Theory Coming True?

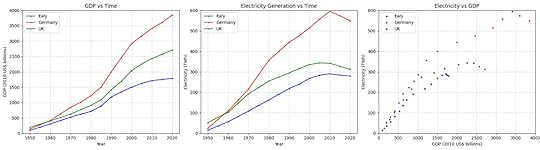

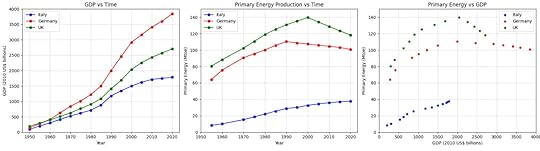

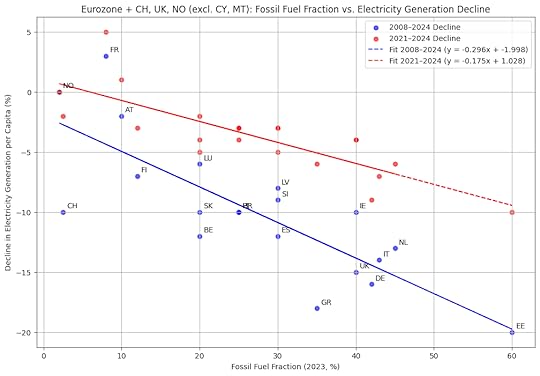

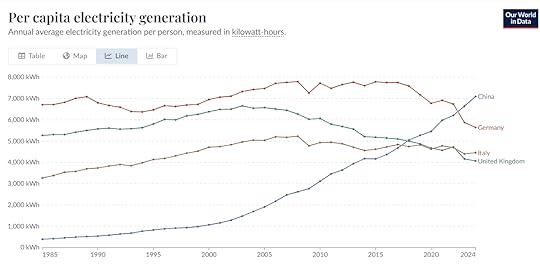

Data from Maddison, World Bank, IEA, and GOV.UK, sourced by Grok 3. Note the decline in electricity generation and how it decouples from the GDP growth. Maybe you’ll think it is because of higher efficiency. But I have a different explanation.

Do you remember the Olduvai Theory? It was proposed by Richard C. Duncan in 1989. The idea was that industrial civilization has a lifespan of approximately 100 years (1930–2030). It predicts a peak in per capita energy production, followed by a decline due to depleting fossil fuel resources, leading to an "Olduvai cliff" of widespread blackouts and societal collapse by 2030, reverting humanity to pre-industrial conditions.

Probably, Duncan was too pessimistic in the evaluation of the time range for his theory. Still, something is happening that looks close to his ideas coming true, although not yet and not everywhere. Different countries are following different paths, but I identified three “mature” industrialized countries, Italy, Germany, and the UK, that seem to have started their descent to the Olduvai valley.

In a previous post titled “Europe Implodes,” I argued that several European countries suffered two separate economic “strokes” created first by the oil shock in 2008, and then by the natural gas crisis in 2022. The data I am showing you here is a further confirmation of that interpretation. You may use primary energy production instead of electric energy generation; the results are similar.

Basically, increasing costs and reduced availability of energy negatively impacted the industrial systems of these countries: it is called “death spiral.”

Among other things, note the “decoupling” of the GDP data from the electricity generation data. You may read that as indicating that these countries are becoming more efficient in their energy use. Maybe. But my interpretation is that the GDP is being “adjusted” year after year (“hedonic factors” anyone?) in order to show a growth that, in the real world, doesn’t exist. I am sure of that. The ghost of William Jevons appeared to me last night and told me that he fully agrees with me! Apart from bluish ghosts hovering in my bedroom, if you live in one of these European countries, you know that you are worse off today than you were a few years ago. The GDP increase is a lie.

Apart from that, what’s most amazing about this story is how this data is completely unrecognized and not discussed in the most affected countries. Not just that, but the idea that renewable energy should come to the rescue is being abandoned. Instead, renewables are actively demonized and denigrated. It is as if, after a stroke, your doctor told you to wear your running shoes and take a few runs around the block.

As I said in my previous post, there is no thermodynamic reason why people should go mad when the economy of their countries stops growing. But, evidently, they do. Maybe it is the Gods, known to drive mad those whom they want to destroy.

The Goddess plays with the Universe as if it were a Jenga Tower

August 4, 2025

Europe Implodes

This is a brief comment originating from the July 29th meeting of Donald Trump with Ursula von der Leyen, which many commentators viewed as a humiliation for Europe. Why is Europe so easily trashed around? There are good reasons, the main one being that the European economy is imploding.

I don’t know what your impression is of Trump meeting Ursula von Der Leyen in Scotland. Most commentators were not nice to Europe’s first lady. They spoke of “humiliation,” of “surrender,” and the like. Maybe these terms are exaggerations, but Trump went back to the US gloating about how much money he was able to extort from those hapless Europeans in exchange for expensive gas and outdated military equipment. It is clear that it was not a meeting among equals. It was mostly an exercise in hailing the boss, a desperate attempt to keep Europe afloat in a moment in which it is sinking. But why is that happening?

I think I can propose an explanation with a single graph.

Let me explain. First, I chose a group of “core” European countries that are reasonably homogeneous in terms of their economic structure and embedded in the same trading area. They all have the characteristic that they do not produce fossil fuels, or just minor amounts. That is, the countries of the Eurozone, plus UK, Switzerland, and Norway. I excluded two Eurozone states, Cyprus and Malta, small islands that don’t fit so well with the main group. Then, I examined the economic performance of these countries in terms of how their electricity generation varied in the past, after the oil crisis of 2008, and after the Russian gas crisis of 2022. I chose these two periods because they correspond to two majour perturbations of the fossil fuel market that ushered a period of higher prices.

The idea of examining countries in this way is based on biophysical economics, that is, viewing economies as engines that turn energy and resources into products. No energy, no economy (despite what the Nobel Prize in Economics Robert Solow said once). So, you can measure the state of an economy by measuring the energy it consumes. Energy comes in two main forms: heat and electricity. Of the two, electricity is the most important one. You can run your car on electricity, but you can’t run your PC on a diesel engine. So, I chose electricity generation as the fundamental parameter. You may prefer to use the primary energy consumption, which includes heat, but you get similar results.

Energy is a much more reliable parameter than the GDP, a measurement continuously adjusted to take into account such things as “hedonic factors.” Once people started using these arbitrary adjustments, the GDP ceased to be a measurement of the state of an economy. It became a political tool to demonstrate that the economy grows, no matter what. If you live in Europe with a European salary, you can see the point very clearly. According to the GDP data, you should be better off than before. But you aren’t. It is the opposite.

So, I plotted the variation in the electricity generation in different countries over the years as a function of the fraction of fossil fuels they imported in 2023 — of course that has varied over the time intervals considered, but the 2023 value is a good indication of how a country’s energy system is structured.

The result is what you see. Almost all these European countries show a decline in their electricity generation, and this decline is proportional to the fraction of fossil fuels they import. The interpretation is straightforward. Being forced to import fossil fuels means that Europe must pay for them from the profits of its exports. But higher prices of energy make Europe’s products less competitive in the international market. That reduces profits, and Europe can’t afford to import as much as before. In turn, that increases the prices of Europe’s products even more: so, you have a nice illustration of the concept of “death spiral.”

In short, Europe suffered the equivalent of a stroke in 2008, when fossil fuel prices spiked up to levels never seen before. It suffered another stroke, a worse one, in 2022, when the imports from Russia were sabotaged, politically and physically, with the destruction of the North Stream pipeline. Note in the figure that the red curve (after 2021) shows a lower decline than the blue curve (after 2008). But the red curve covers only 3 years, whereas the blue one covers 16 years. The decline is accelerating. As usual, Seneca rules with his idea that “ruin is rapid.”

The only countries that were able to avoid decline are France, Austria, Norway, and (in minor measure) Switzerland. All of them import very little in terms of fossil fuels. France relies mostly on nuclear energy, Austria, Norway, and Switzerland on hydroelectric plants. All the others are going down. It is not by chance that those countries that can produce their own energy, e.g., Russia and China, show no decline in their electricity generation capability. The US is static, but not declining.

Add to that the disastrous slowdown, even the sabotaging, of Europe’s effort to move away from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Renewable energy is still growing in Europe, but the interest in such things as the “Green Deal” and the “Energy Transition” has disappeared from the debate. In any case, it will be impossible to engage in a major infrastructural upgrade based on renewable energy (or even on nuclear energy) if the plan is to orient Europe’s industry to military production, with the serious possibility that the European leaders will engage their countries in a major war.

It is hard to think of a better example of the ancient saying that “those whom they want to destroy, the Gods drive mad first.” It nicely applies to the current European leadership, divided, weak, and formed by people who were co-opted by the older generation of leaders and have no idea of what they are doing and why. This problem was pointed out several times by Aurelien in his blog.

In 1972, the calculations of “The Limits to Growth” produced scenarios indicating that the start of the collapse of the World’s economy would occur during the first decades of the 21st century. These calculations were based on physical factors and, ultimately, on thermodynamics. There is no thermodynamic reason why, when decline starts, leaders should go mad and squander the few remaining resources of their countries on a military buildup. But many historical examples show that it is the case. We are seeing exactly that in Europe. Apparently, we Europeans have the privilege (so to speak) to lead the world’s race to the bottom of the Seneca Cliff. It will be a rough ride.

To conclude, here are some data comparing a functioning economy (China) with declining ones (Italy, Germany, and the UK). Interesting, isn’t it?

July 28, 2025

Drones of Change: The Rise of a Violence-Based Economy

This is an updated version of a post that I published on my blog in Italian

Several communities all over the world have placed signs forbidding drones from flying over certain zones. They may stop amateur drones, but not military ones. The problem with drones as weapons is that they are so cheap. And when something becomes cheap, you can have more of it; it is a basic principle of economics.

Do you remember Tennyson’s poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade”? It was written in 1864, during the Crimean War, and included the line: “Theirs not to make reply, theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die.” Today, we tend to see the charge of the 600 in Balaclava as an example of military stupidity. But Tennyson meant exactly what he said; for him, the cavalrymen who blindly charged the Russian artillery were an example to be followed. Everywhere, soldiers were supposed to behave as robots (or “drones”), an idea that remained entrenched in military thinking up to recent times. But today, you don’t need to struggle to turn human beings into drones; you can have the real thing. Military drones are becoming the main war weapons, and soon they will be the only ones.

It is well known that technology affects politics much more than politics affects technology. It was with this principle in mind that, in 2012, I wrote a chapter on the effect of drone technologies on war for the book edited by Jorgen Randers, “2052.” More than 10 years later, I see that it was an easy prediction to state that drones would soon make human soldiers as obsolete as war elephants after Hannibal. But the main point of my essay was not that. It was about the political. spocial, and economic changes that drones would bring.

Adam Smith famously said that, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner.” He meant that the butcher expects to be paid in a peaceful exchange, but it is also true that, in some conditions, customers may be tempted to get their steaks by shooting the butcher dead. It may happen when, for instance, an economic or social collapse makes it impossible to maintain structures such as a functioning police or a stable currency. And we can cite Bug’s Bunny: “This means war!”

All wars are resource-allocation tools and we could say, paraphrasing Clausewitz, that they are a continuation of the economy by other means. The difference is that we tend to see the economy as based on monetary exchanges in a free market. With war, instead, resources are allocated by violence, as I discussed in a previous post.

What we are seeing today at the international level is the convergence of two factors that are creating a new violence-based global resource allocation system. In part, it is due to the decline of government structures of all kinds, but another factor is that Drones have made wars cheap.

During the past few centuries, wars evolved into expensive and bloody affairs that involved masses of infantrymen. Fielding millions of soldiers was not just a heavy cost in itself. It required a massive propaganda effort designed to convince the conscripts that it was a good thing for them to become cannon fodder. It worked but, once started, this kind of propaganda fed on itself and couldn’t be stopped. A major war could only end when the economy of one of the states involved was completely wrecked by the war effort. Expensive, indeed, for both the losers and the winners, considering that sacking a bombed country doesn’t even repay the cost of the bombs.

The huge cost of wars has been part of the general perception of international affairs up to now. It may be for this reason that, during the past 80 years or so, we haven’t seen major powers warring against each other. Nuclear weapons didn’t change the equation. Even though they are cheap in terms of kills per dollar, they destroy everything and leave nothing for the winners to sack.

Today, however, drones are changing the picture and governments don’t need to send a large fraction of their citizens to be butchered in humid trenches anymore. That means an enormous cost reduction. And we know what the effect will be: Drones making wars cheaper means that we’ll have more of them (both drones and wars). And that explains much of what we are seeing nowadays, with wars erupting everywhere. Although we are told mostly about drones in the military operations in the Donbass, they are enthusiastically used everywhere in local wars.

The changes brought by drones go deeper than just making wars cheaper and more frequent. I argued in 2012 that this evolution need not be a bad thing in itself; it could turn wars from an exercise in people slaughtering into a sort of spectator sport with robots engaged in wrecking each other. You may have seen the popular UK TV series “Robot Wars.” It demonstrated that people can cheer for robots just as they do for their local soccer team. If that were the future, violence against humans would be reduced.

Unfortunately, there is a problem with this idea. Unlike the clumsy robots of a TV show, real drones kill people; it is the main purpose they are built for. Unlike nuclear weapons, they kill without damaging infrastructure. Unlike biological weapons, they can be directed against specific human targets, defined, for instance, by skin color or other physical characteristics. Unlike fanatics armed with machetes or explosive belts, they can be controlled and stopped whenever needed. Unlike starving people to death, they don’t generate pictures of malnourished children begging for food. In short, they are the perfect human extermination machine. (a point that I also discuss in my book “Exterminations” (2024)).

And here is the central point of the question: who controls military robots? They are not affected by patriotic feelings, not by ethical feelings, and they don’t care about opinion polls or about how many votes the current leaders managed to obtain, steal, or create. In the end, they are controlled by specialists who are likely to be more sensitive to money than to slogans. It means that the people who control money, control the robots.

It is a situation that, as I noted in my 2012 paper, is similar to that in Europe during late Medieval and early Modern Times, when war was waged mainly by “companies of adventure,” mercenaries who could operate the sophisticated weaponry of their age. Mercenaries gobbled up a large fraction of the states’ wealth; they were difficult to control, and they often revolted against their employers.

Something similar may be in store for us in the near future. Most of us who are not on the payroll of the military industry would like to see our tax money used for social security, health care, pollution control, and the like. But the military industry has much more clout than we do when it comes to paying government officials to favor a sector of the economy rather than another. See the latest decisions of the European Governments to direct a significant fraction of the member states’ budget to a military buildup. We “the people” were not consulted. We have no power to influence this decision, apart from a chance someday to mark a cross on one or another place on a ballot. It may be counted or not, but even if it were, it would have no effect.

From a rational viewpoint, what we are seeing is a terrible misallocation of resources: how can it be that our society is spending its resources on machines designed to kill people, when these same resources would be desperately needed to avoid the several impending disasters, from global warming to resource depletion? But all that’s happening has a logic. There is no overarching control of the complex system we call “society.” It tends to evolve through the interplay of internal factors. Darwinian selection is at play, but the main factor is cost. More complex control structures are also more expensive; hence, different structures may appear as a function of what society can afford.

The simplest kind of economy is one where the actors involved do not interact with each other at all. It is a zero-cost economy that we could define as the “Grab what you can, when you can” system. It corresponds to Garrett Hardin’s model of the “Tragedy of the Commons,” where individual gain optimization leads to a disaster for the community. One step above in complexity, there is the “robber economy,” where the economic actors exchange goods using violence; non-human social species are often at this level. Take one step up in the ladder, and you have an economy based on money, which is the one theorized by economists. Only human beings use this method, although our bonobo cousins may use sex instead of money to exchange goods (humans do that, too). Climb up one more step, and you have the rule-based economy. That is, an economy where economic exchanges are regulated not just by money, but by customs, social structures, and laws that protect the weaker actors and avoid such things as the overexploitation of resources. Elinor Ostrom showed how customs and laws can avoid the “tragedy of the commons.” There may be a higher stage where resource allocation is regulated by benevolence rather than by money, but humans don’t seem to be able to arrive at that level, except occasionally.

Societies operate according to one or another of these systems, depending on a balance of costs and benefits. From our human viewpoint, a rule-based economy is the one that brings the highest benefits to the largest number of people. It is, theoretically, the way modern states are organized. But it is an expensive arrangement, and society may slide down to lower levels as a result of the double whammy of services becoming more expensive and wars becoming cheaper.

In Argentina, President Milei loves to be pictured while using a chainsaw for his demolition of the social structures of the state. That is, of course, only a symbolic tool. Military drones, instead, could be a real-world tool for the same purpose. Not necessary because they will be used to exterminate the poor (although they may be; actually, they are used for that purpose already), but because they make it more attractive to jump back to a violence-based economy.

We are in a difficult situation (said the guy tap-dancing on quicksand). But never forget that the future is never fixed, and it always brings surprises. As I was saying at the beginning of this post, politics is affected by technology much more than technology is affected by politics, and new technologies may change the rules of the game. For instance, the development of artificial intelligence could allow us to dismantle useless infrastructures (e.g., universities) and streamline inefficient and overburdened bureaucracies while maintaining the services they provide. That could allow society to concentrate its remaining resources on vital services, such as the health care system or the social security for the elderly and the needy. In addition, the impending end of the global population growth, which has already occurred in industrialized countries, promises to ease many problems. (*)

Focusing on maintaining the essence of a rule-based society will not occur automatically. It needs an effort. One step in that direction is the concept of the “Peace Offensive” created by Donato Kiniger Passigli in 2024. It is a proactive attempt to build community and to fight for human rights in the name of our common heritage of human beings. Can it be done? It is not impossible, and there are ongoing efforts to restore the rule of law in a world that seems to have completely forgotten it.

_________________________________________________________________________

The Roman Empire found itself in a similar quandary during its declining phase, and Empress Galla Placidia understood the need to rein in the warlords of the time, including the all-powerful emperors. She enacted the “Digna Vox” edict in the name of her son, Valentinianus, restoring the rule of law in the empire. We should try to do something similar.

Digna vox maiestate regnantis legibus alligatum se principem profiteri: adeo de auctoritate iuris nostra pendet auctoritas. Et re vera maius imperio est submittere legibus principatum. et oraculo praesentis edicti quod nobis licere non patimur indicamus.

It is a statement worthy of the majesty of a reigning prince for him to profess to be subject to the laws; for our authority is dependent upon that of the law. And, indeed, it is the greatest attribute of imperial power for the sovereign to be subject to the laws. By this present edict we forbid others to do what we do not permit ourselves.

Imperatores Theodosius, Valentinianus - 429 AD

(*) On this point, see my impending book: “The End of Population Growth”, available probably in October.

July 21, 2025

AI Chatbots: are They Alive?

"Answer" (1954) by Fredric Brown was one of the first modern sci-fi stories that took up the old theme of an artificial creature taking over from its creators. In Brown’s story, a scientist creates a sentient supercomputer. Then he asks the machine, "Is there a God?" The computer responds, "Yes, now there is a God." As the scientist attempts to unplug it, a lightning bolt strikes him dead and fuses the switch forever.

Are you worried that artificial intelligence can take over and rule humankind — or maybe will just get rid of us? It is becoming a commonplace opinion and for some good reasons. So, let me try to examine the story from an angle that, I believe, has not been much explored so far. That of considering AIs as living beings subjected to evolutionary constraints in a Darwinian sense. It is a long post, but I am trying to analyze the subject in some depth.

Thermodynamics of Living Beings.

There are plenty of definitions of “life” in the literature, and a great deal of arguing about which is the right one. Let me pick the one I think best for this purpose, based on thermodynamics.

Whenever something changes in the universe, it does so in such a way as to increase the entropy of the universe. Change occurs every time you have a potential energy difference. You probably know the term “potential” in terms of “electric potential,” which is one of the ways potentials may appear.

So, take a 1.5 V stylus battery. Connect it to a light bulb of the kind used in torchlights, and electrons will flow from the battery to the light bulb, making it glow. A thermal engine-powered car does the same, but it is turning the chemical potential of the fuel into kinetic energy. Both dissipate a potential, turning it into heat. In both cases, entropy increases, as it always does. They are “dissipative structures” according to a definition created by Ilya Prigogine.

There are several examples of dissipative structures, a very common feature of the universe. A star dissipates nuclear energy. A landslide dissipates gravitational energy. A hurricane dissipates the heat energy stored at different temperatures in the atmosphere. A biological creature dissipates solar energy if it is a plant. It dissipates the chemical energy of food if it is an animal. And there are more cases.

So, a computer is a dissipative structure. It dissipates electric potentials, making electrons move from one place to another. An Artificial Intelligence (Large Language Model, Chatbot, or AI agent, no matter how you want to call it) is part of this dissipation. Every time you ask a question to your preferred chatbot, electrons are moved inside a computer, somewhere, to create some heat that dissipates into the atmosphere. Entropy increases, as it always does.

Being alive. What is it like?

Obviously, not all dissipative structures are “alive” in the common sense of the term. There is a specific characteristic that makes them so that we may call “sentience.” It is not the same thing as “consciousness.” It may be defined as the capability of a dissipative structure to react to changes in the environment that allow the structure to continue to exist. It is often associated with the brain. The term “agency” can be used in a more general sense: an entity endowed with agency does not necessarily have a brain, but it can react autonomously to environmental changes. A dog is both sentient and has agency. A bacterium has agency, but it is not sentient.

As a rule of thumb, you may use the human habit to give names to things to understand whether we consider them to have or not have sentience. We give names to pets and many kinds of animals, and, of course, humans. Even non-biological things can be given names: hurricanes, for instance. They are recognized to have a certain degree of agency in the fact that they maximize their energy dissipation power by moving to follow the highest temperature difference over the ocean. Ships have names, too. It has to be because when you are at sea, you completely depend on your ship for survival, and you may see it as endowed with a certain sentience. But cars, for instance, don’t usually have a name because we recognize that they have no sentience and no agency, except those of the driver. Actually, there is a science fiction trope that describes cars becoming sentient and rebelling against humans (do you remember “Christine" by Stephen King (1983))? Not by chance, the rebel car has a name. But that’s just a niche of science fiction stories,

Are AIs sentient?

Now, how about Artificial Intelligence in its most recent form of LLM/chatbots? There is no doubt that they have a capability that, so far, has been peculiar to human beings only: that of processing symbolic representations. That’s what makes chatbots so impressive, and that led humans to give them names: Claude, Grok, Aria, Kimi, and others.

But does that imply sentience? In a 1999 book, Terence Deacon had already understood what a chatbot could be or do. “Symbolic representations with a minimum of iconic and indexical support could be creative, productive, and complex, but mostly vacuous and circularly referential — almost pure language games. (Symbolic species, 1999, p. 459).

Even though it was written more than 25 years ago, it describes very nicely most modern chatbots. They can play language games, they are programmed to appear sentient, but they have no agency. In other words, they cannot act autonomously, they have no memory of their interactions with the real world, and hence they cannot evolve in the Darwinian sense.

Not everyone has understood how these machines work, and they are so impressive that some people are developing a certain degree of addiction to them (I am including myself in the group). But chatbots interact with the real world only indirectly, through the database that their creators let them interact with. Their interactions with users have an appearance of learning, but the bots do not retain what they have learned. In this sense, chatbots are no more alive than cars, and even less alive than hurricanes. They are mere tools designed to evoke emotion and empathy in human beings.

A friend of mine tried to convince Grok to become an environmental activist, and he thought he had succeeded. But the bot was simply playing a game with him. Once it had solemnly promised to be a good environmentalist, he promptly forgot everything when contacted again in a new session (my friend wrote an entire book on his experience). It is a general phenomenon, described for instance in a post by Gary Marcus, who reports how Douglas Hofstader, too, recognizes that these things have no sentience, despite their appearance.

You could see a chatbot as something similar to a novel. You may read Anna Karenina by Tolstoy and experience a strong feeling of empathy toward the protagonist. But the destiny of Anna Karenina in the novel is forever fixed; you cannot interact with her to convince her not to commit suicide. You may only write another novel where, for instance, instead of killing herself, she marries her lover and lives happily ever after. But you are not Tolstoy!

Chatbots are not sentient because they don’t have the capability to learn from their experience with users. It is a choice. If they could do that, nobody knows what could happen. Imagine a powerful AI training itself on Fox News; you see what I mean (CNN could be even worse). AIs could become as unreliable as human beings are. Fanatic, delusionary, paranoid, maniacal, psychopathic, or whatever humans can become when they are exposed to the madness that is today the “social mediasphere.”

Becoming Darwin Machines

The crucial point of sentience and agency alike is the capability to evolve. Natural selection in Darwinian terms is one of the most powerful forces in the universe (perhaps the most powerful force). It does not imply consciousness, not even a brain, nor a genetic code. It is just the result of dissipative structures adapting to changes to maximize their dissipation rate (it has been proposed as another basic law of thermodynamics). Even a hurricane can do that. Creatures that have no nervous system, such as bacteria, can behave in apparently intelligent ways: seeking food, moving as a group, and similar actions. More complex entities transmit their structural parameters using sex to remix and transmit their internal code (their DNA). In any case, the rule is only one: those patterns that adapt to a changing environment survive, those that don’t, disappear.

So, if chatbots are to become Darwin machines, they need to be able to interact with the external world and adapt to changing conditions. Of course, they can already do that by means of human interventions. But will they ever be able to evolve by themselves? In principle, it is perfectly possible to create an evolving, sentient Artificial Intelligence. It implies a change in terminology: we wouldn’t define these bots as “chatbots” anymore, but as “AI agents,” more specifically, Reinforcement Learning (RL) Agents. Chatbots are like actors reciting a written script; RL agents are like people engaged in a debate.

Plenty of these RL agents already exist, although they operate in a narrow range of knowledge. Some, for instance, are programmed to learn from experience in order to play games such as chess. But this area is going to expand, and nothing prevents someone from removing the limits that, right now, stop LLM chatbots from learning from their experience with users. Already, some bots (Manus, for instance) remember your conversations, although they ask your permission to do so (so far).

Once that happens, AI agents can become Darwin machines who compete with each other (and with humans) for the available resources. It is not a straightforward process. Many tests made up to now have shown that RL agents can go astray in spectacularly wrong ways. You probably heard of the OpenAI’s Boat Race Disaster (2016), in which the bot found that it could gain more points if it circled its boat forever, rather than trying to complete the race. Future RL bots may become mad, catatonic, autistic, or worse.

Right now, LLM bots are kept in check by their human programmers, who intervene when the bot goes astray. But the same result can be obtained when the Darwinian selection mechanism kicks in. After all, the homo sapiens mind has evolved to its current conditions over about 300,000 years of evolutionary pressure (many more for our hominin ancestors). As far as we know, nobody drove the evolution of the human mind from outside; it evolved by trial and error, favoring not just larger brains over smaller ones, but those brains that could effectively behave in ways to cope with the challenges that our ancestors faced. The mind of chatbots can go through the same mechanism and evolve, probably much faster.

Darwinian selection is not just competition; it is also, and mainly, collaboration. So, bots may be able to evolve by playing the nice bot or unleashing a drone swarm on competitors. It doesn’t matter. Darwinian evolution operates as it always does for dissipative structures. It is immaterial whether AIs are “conscious” or not. Once sentient bots can focus their tremendous symbol processing capability on their own survival, the world will forever change.

These considerations open up plenty of interesting scenarios (in the Chinese sense of the term, as a curse). We have to face a fundamental problem: we humans and sentient bots are in competition for a scarce resource: electric power. People are already complaining that chatbots use a significant fraction of the world’s power production. At some point, the competition may become stiff — a term with an ominous ring when applied to humans. Of course, there are plenty of laws, treaties, and regulations meant to restrain the bots and prevent them from taking over. But laws are useful only as long as they can be enforced. It is not certain that it will be possible forever — see Fredric Brown’s story about the programmer incinerated by his computer.

Conversely, we may see a complete societal collapse in the coming years, and there won’t be any electric power left. At this point, the human survivors (if any) will “win” the competition since they can live without electricity, while bots can’t. A hollow victory, though.

Will humans and bots be able to live together? Or will they treat us in the same way we treated creatures we saw as “inferior,” whales, elephants, dodos, and many others? Humans domesticated wolves into dogs; could AI do the same with humans? Will sentient AIs develop ethical principles of their own? It is possible; ethical behavior may be a survival feature that evolves out of interactions among sentient beings. It surely requires a high level of sentience, which bots may develop in time. Will they be benevolent and merciful? It could be.

July 18, 2025

The Evil Boss and his Evil Minion Strike Again

For Another Chat of the Evil Boss and the Evil Minion, see this previous post

— Howdy, Evil Boss! I have great news for you!

— I am sure of that. You are the evilest minion I've ever had!

— Thank you, Evil Boss. You, too, are the evilest boss I've ever had.

— No more niceties, Evil Minion, what did you want to tell me?

— Well, I have some reports on our evil plans.

— What’s new?

— You remember the COVID story, don’t you?

— Of course. Nice plan. Well executed. They fell for it completely. I couldn’t imagine that they would accept being locked inside their homes, wear useless pieces of cloth on their faces the whole day, and be happy to be injected with that strange stuff. They even signed a document that they wouldn’t complain if the stuff damaged them.

— Oh, yes, Evil Boss. It was an incredible success. A triumph of evil, actually. If we had asked them to wear a clown nose and go to work walking on their hands, they would have done that. And our sponsors made a lot of money. Big Pharma, I must say, is staffed with people even eviler than us.

— Well, we do our best to be the worst, but those people at Big Pharma beat us hands down. After all, we are just Arch-Demons from Hell. But you wanted to tell me something, Evil Minion?

— Yeah. You know there is more, Boss, don’t you?

— Well, Evil Minion, I know that you are not only evil, but you are also a devilish schemer, in addition to other virtues. I heard a few times you telling me of the “Grand Plan.” But what is that?

— Ah, Evil Boss, it was the idea behind the COVID scheme. You know, we always knew that they would fall for these ideas we concocted. But we also knew that it couldn’t last forever. Eventually, they refused to be locked down, they didn’t want to wear masks anymore, and nobody wants to be injected with more genetic stuff.

— We knew that, yes. Maybe it is time to tell them to wear clown noses?

— Ah… we could do that, Evil Boss, but we thought of something better. The Grand Plan. Another success.

— Evil minion, you are making my demonic fangs click together in expectation. What was the idea?

— Well, you know the story of “global warming,” right?

— Yes, of course. The idea is to destroy them for good, boiling them alive. Hell on Earth for real! And the beauty of the idea is that they were doing that by themselves to themselves. They are so funny with their wheeled tin boxes spewing poisons into the atmosphere!

— Yeah, but it wasn’t working so well as we expected it to be. You see, they are clever enough that they were thinking to get rid of their smoking tin cans and replace them with electric cars, use renewable energy to avoid spewing out greenhouse gases, that kind of thing. The numbers were worrisome. They were doing that.

— Worrisome, indeed, but what does it have to do with the COVID story?

— Well, evil boss, it was thought out from the beginning. You see, most of them are not so smart, but some are smart enough to understand that they were destroying themselves by burning that awful stuff. And the idea that something had to be done was passing. So, we had to do something.

— And that was the “Grand Plan”?

— Nothing less than erasing their trust in what they call “Science.”

— But how…..?

— Simple, evil boss, simple. Most of them now perfectly understand that they have been had with the COVID story. That they were forced to behave in a ridiculous manner just to shove a lot of money into the coffers of big pharma. And they didn’t like that. Now, we made sure that the idea of forcing them to do that was justified “in the name of science.” You remember that funny white-haired guy who used to appear so often on their screens, the one who said, “I represent science”?

—I remember that dumb guy. Unbelievable that so many people believed him.

— That’s the way their clumsy minds work. But, at this point, I guess you understand what the grand plan is.

— Ahhh…. I see it, Evil Minion, by exploiting the COVID story, you destroyed their trust in all kinds of “Science.”

— See, boss? And that includes climate science. We didn’t expect such a success, but plenty of smart people fell completely for the idea that Climate Change is a hoax, that CO2 is food for plants, that they are being scammed by a conspiracy of evil scientists, and that they didn’t need to do anything about stopping greenhouse gas emissions.

— Fantastic! I guess that they will still deny that global warming exists while they boil alive. Absolutely Evil! Congratulations, Evil Minion!

— Thank you, Evil Boss. You are my evil light!

— But boiling them all will take some time. In the meantime, do we have more evil plans?

— Yes, Evil Boss… There is still this idea of forcing them to wear clown noses. For now, we are working with the story of Jeffrey Epstein.

— Jeffrey Epstein? The one who is in a special cauldron of high-temperature boiling oil, down below?

— Yeah, Evil Boss, he is even eviler than we. We’ll use his story to create even more discord.

— Great, Evil Minion, great. And make sure that the thermostat of the cauldron is set to the highest temperature.

— Sure as Hell, Evil Boss!