Alexandra Sokoloff's Blog, page 6

November 28, 2018

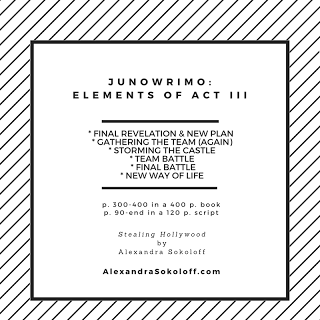

Nanowrimo home stretch: Elements of Act III

by Alexandra Sokoloff

Okay!! It's the last week - we're into Act III, now! Or maybe, even probably, you're not that far yet, which is perfectly fine. As long as you're writing, it's all good. The book will be done when it's done.

But if you are into Act III, here are the prompts for that last act.

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

- Alex

ELEMENTS OF ACT THREE

Act Three is generally the final 20 to 30 minutes in a film, or the last 70 to 100 pages in a 400-page novel. The final quarter, and the shortest quarter.

It is often divided into these two major sequences:

1. Getting there (STORMING THE CASTLE)2. The FINAL BATTLE itself

Plus a shorter RESOLUTION/NEW WAY OF LIFE.

And it usually contains these elements:

• Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero/ine will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelation of the second act climax.• There may be a TICKING CLOCK• The Hero/ine may REASSEMBLE THE TEAM, and there may be another short TRAINING SEQUENCE and/or GATHERING THE TOOLS sequence• The team often goes in together, first, and there is a big ENSEMBLE BATTLE• In this battle, we possibly see the ALLY/ALLIES’ CHARACTER CHANGES and/or gaining of desire • We also get the DEFEAT OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS• Then the hero/ine goes into the FINAL BATTLE to face the antagonist alone, MANO A MANO• The final battle takes place in a THEMATIC LOCATION: often a visual and literal representation of the HERO/INE’S GREATEST NIGHTMARE, and is very often a metaphorical CASTLE. Or a real one! It is also often the antagonist’s home turf.• We see the protagonist’s character arc• We may see the antagonist’s character arc, too (but often there is none)• We get a glimpse of the TRUE NATURE OF THE ANTAGONIST• Possibly there is a huge FINAL REVERSAL or reveal (twist), or even a whole series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and It’s A Wonderful Life)• FULL CIRCLE: Not every story uses this, but often the hero/ine returns to a place we saw at the beginning of the story, and we see her or his character growth.• RESOLUTION: We get a glimpse into the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it• FINAL BOWS: We need to see all our favorite characters one final time• CLOSING IMAGE: Which is often a variation of the Opening ImageAll right, let’s look at these more closely.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist.

And sometimes that’s really all there is to it: one final battle between the protagonist and antagonist. In which case some good revelatory twists are probably required!

By the end of the second act, pretty much everything has been set up that we need to know — particularly who the antagonist is, which sometimes we haven’t known, or have been wrong about, until it’s revealed at the second act climax. Of course, sometimes, or maybe often, there is one final reveal about the antagonist that is saved till the very end or nearly the end, as in The Usual Suspects and The Empire Strikes Back and Psycho.

We also very often have gotten a sobering or terrifying glimpse of the TRUE NATURE OF THE ANTAGONIST — a great example of that kind of “nature of the opponent” scene is in Chinatown, in that scene in which Jake is slapping Evelyn and he learns the truth about her father.

There is often a new, FINAL PLAN that the hero/ine makes that takes into account the new information and revelations. As always with a plan, it’s good to spell it out.

There’s a locational aspect to the third act: the final battle will often take place in a completely different setting than the rest of the film or novel. In fact, half of the third act can be, and often is, just getting to the site of the final showdown. One of the most memorable examples of this in movie history is the STORMING THE CASTLE scene in The Wizard of Oz, where, led by an escaped Toto, the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion scale the cliff, scope out the vast armies of the witch (“Yo Ee O”) and tussle with three stragglers to steal their uniforms and march in through the drawbridge of the castle with the rest of the army (an example of a PLAN BY ALLIES). The Princess Bride also has a literal Storming the Castle scene, with the Billy Crystal and Carol Kane characters waving our team off shouting, “Have fun storming the castle!”

A sequence like this, and the similar ones in Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, can have a lot of the elements we discussed about the first half of the story: a PLAN, ASSEMBLING THE TEAM, ASSEMBLING TOOLS AND DISGUISES, TRAINING OR REHEARSAL.

I’m not just talking about action and fantasy movies, here. You see a truncated version of this team battle plan and storming the castle scene in Notting Hill, when all of Will’s friends pile into the car to help him catch Anna before she leaves.

And of course speed is often a factor — there’s may be a TICKING CLOCK, so our hero/ine has to race to get there in time to – save the innocent victim from the killer, save his or her kidnapped child from the kidnapper, stop the loved one from getting on that plane to Bermuda…

NO. DO NOT WRITE THAT LAST ONE.

Most clichéd film ending ever. Throw in the hero/ine getting stuck in a cab in Manhattan rush hour traffic and you really are risking audiences vomiting in the aisles, or readers, beside their chairs. This is in fact the most despised romantic comedy cliché on every single “Romantic Comedy Clichés” website out there.But when you think about it, the first two examples are equally clichéd. Sometimes there’s a fine line between clichéd and archetypal. You have to find how to elevate —or deepen — the clichéd to something archetypal.

Even if there’s not a literal castle, almost every story will have a metaphorical Storming the Castle element. The hero/ine usually must infiltrate the antagonist’s hideout, or castle, or lair, and confront the antagonist on his or her own turf, a terrifying and foreign place: think of Buffalo Bill’s basement in Silence of the Lambs, and the basement in Psycho, and the basement in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The castle can be a dragon’s lair (How to Train Your Dragon), or a dream fortress (Inception), or a church (a million romantic comedies).

Putting the final showdown on the villain’s turf means the villain has home-court advantage. The hero/ine has the extra burden of being a fish out of water in unfamiliar territory (mixing a metaphor to make it painfully clear).

I’ve noticed that in most films, there is a TEAM BATTLE first. The allies get to shine in this one: their strengths and weaknesses are tested, PLANTS are paid off, and allies who have been at each other’s throats for the whole story suddenly reconcile and work together. We also often get the DEFEAT OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS (if we’ve come to hate a secondary opponent, we need to see them get their comeuppance in a satisfying way — think of Fanny and Lucy Steele cat fighting each other in Sense and Sensibility, and Belloq, General Strasser, and Major Toht’s faces melting in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The TEAM BATTLE is generally a big, noisy SETPIECE scene.

And then, almost always, the hero/ine must go in to the FINAL BATTLE to face the antagonist alone, mano a mano.

So if this is the pattern we see over and over again, how can we possibly make it fresh?

Well, of course — look at books and films to see how your favorite storytellers do it.

Silence of the Lambs is a perfect example of elevating the cliché into archetype. The climax takes place in the basement, as it also does in Psycho, and Nightmare on Elm Street. This basement setting is no accident: therapists talk about “basement issues” —which are your worst fears and traumas from childhood — the stuff no one wants to look at, but which we have to look at, and clean out, to be whole.

But Thomas Harris, in the book, and the filmmakers, bringing it to life in the movie, create a basement that is so rich in horrific and revelatory and mythic (really fairy tale) imagery, that we never feel that we’ve seen that scene before. In fact I see new resonances in the set design every time I watch that film… like Mr. Gumb (Buffalo Bill) having a wall of news clippings just exactly like the one in Crawford’s office. That’s a technique that Harris uses that can elevate the clichéd to the archetypal: layering meaning.

But even more than that: Gumb’s basement is Clarice’s GREATEST NIGHTMAREcome to life. Lecter has exposed her deepest trauma, losing the lamb she tried to save from spring slaughter, and now she’s back in that childhood crisis, trying to save Catherine’s life (if you’ll notice, even the visual of Catherine clinging to Mr. Gumb’s fluffy white dog looks very much like a little girl holding a lamb…)

Nightmare on Elm Street takes that clichéd spooky basement scene and gives it a whole new level, literally: the heroine is dreaming that she is following a suspicious sound down into the basement, and then there’s a door that leads to another basement, under the basement. And if you think bad things happen in the basement, what’s going to happen in a sub-basement?

Comedy characters have a different kind of GREATEST NIGHTMARE.

Suppose you’re writing a farce. I would never dare, myself, but if I did, I would go straight to Fawlty Towers to figure out how to do it (and if you haven’t seen this brilliant TV series of John Cleese’s, I envy you the treat you’re in for). Every story in this series shows the quintessentially British Basil Fawlty go from rigid control to total breakdown of order in the side-splitting climax. It is the vast chasm between Basil’s idea of what his life should be and the chaotic reality that he creates for himself over and over again that will have you screaming with laughter.

Another very technical lesson to take from Fawlty Towers —and from any screwball comedy or farce — is how comedies use speed in climax. Just as in other forms of climax, the action speeds up in the end, to create that exhilaration of being out of control — which is the sensation I most love about a great comedy.

In a romance, the Final Battle is often the hero/ine finally overcoming his or her internal blocks and making a DECLARATIONor PROPOSAL to the loved one. And I’ve noticed that a lot of romances do the declaration in a one-two punch, two separate scenes: the recalcitrant lover makes his or her declaration, even does some groveling, apparently to no avail, and only in a later, final scene does the loved one show up with a declaration of his or her own.

An archetypal setting for the Final Battle in romantic comedy is an actual wedding. We’ve seen this scene so often you’d think there’s nothing new you can do with it. But of course a story about love and relationships is likely to end at a wedding.

So again, if you’re writing this kind of story, make your list and look at what great romantic comedies have done to elevate the cliché.

One of my favorite romantic comedies of all time, The Philadelphia Story, uses a classic technique to keep that wedding sequence sparkling: every single one of that large ensemble of characters has her or his own wickedly delightful resolution. Everyone has their moment to shine, and insanely precocious little sister Dinah pretty nearly steals the show (from Katharine Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant!!) with her last line: “I did it. I did it all.”

(This is a good lesson for any ensemble story, no matter what genre — all the characters should constantly be competing for the spotlight, just as in any good theater troupe. Make your characters divas and scene-stealers and let them top each other.)

Now, you see a completely different kind of final battle in It’s A Wonderful Life. This is not the classic, “hero confronts villain on villain’s home turf” third act. In fact, Potter is nowhere around in the final confrontation, is he? There’s no showdown, even though we desperately want one.

But the point of that story is that George Bailey has been fighting Potter all along.

There is no big glorious heroic showdown to be had, here, because it’s all the little grueling day-to-day, crazymaking battles that George has had with Potter all his life that have made the difference. And the genius of that film is that it shows in vivid and disturbing detail what would have happened if George had not had that whole lifetime of battles, against Potter and for the town. In the end, even faced with prison, George makes the choice to live to fight another day, and is rewarded with the joy of seeing his town restored.

This is the best example I know of, ever, of a final battle that is thematic — and yet the impact is emotional and visceral. It’s not an intellectual treatise; you live that ending along with George, but also come away with the sense of what true heroism is.

And the wonderful final battle in The King’s Speech is just Colin Firth facing a microphone and delivering a nine-minute radio broadcast. But we’ve seen him fail this moment because of his speech impediment time and time again in SET UPS; and this time the STAKES couldn’t be higher: it’s his first radio broadcast as King, and he has to convince his already war-weary country to support a war against Hitler.

So when you sit down to craft your own third act, try looking at the great third acts of movies and books that are similar to your own story, and see what those authors and filmmakers did to bring out the thematic depth and emotional impact of their stories (We’ll be doing more of that in the next chapter, too.)

RESOLUTION AND NEW WAY OF LIFE

After the final battle is fought and won, we want to get a sense of the NEW LIFE the hero/ine is going to lead now that they’ve been through this incredible journey.

One of the greatest images of a NEW WAY OF LIFE ever put on film is from Romancing the Stone: the yacht parked in the Manhattan street outside Joan Wilder’s building, and Jack standing on deck waiting for her, with those alligator boots on. It’s a complete PAYOFF of his and her DESIRE lines (and the alligator boots are a great light touch that keeps it all from being too sugary), and a clear indication of what their life is going to be like from now on. Would this have worked as well if that yacht were in a harbor? No way. It’s the extravagance and quirkiness of the gesture that makes it so grandly romantic. It never fails to spike my endorphins, and that’s what these endings are all about.

FULL CIRCLE

Not all stories use this technique, but very, very often at the end of the story the hero/ine returns to the setting of the beginning. And often storytellers use a visual contrast in how that setting appears in the beginning and the end, to show the protagonist’s change in character or attitude.

In the beginning of The Godfather, Don Corleone is in his study, sitting behind his desk in a chair that looks like a throne, holding court and deciding the fates of his supplicants. In the final moments of the story, Michael Corleone stands at that same desk with his subordinates kissing his ring: he has become the Godfather. Early on in Act I of Romancing the Stone, pathologically shy Joan Wilder attempts to leave her apartment and is immediately set upon by street vendors, and we see how incapable she is of handling people and life in general. In Act III, she has returned from her adventure a changed woman, and we see her walking down that same street in her full Kathleen Turner goddesslike radiance, waving off those same street vendors both regally and casually.

You don’t have to use this Full Circle technique, but it can work well to bookend a story and depict CHARACTER ARC. Start to look for it in movies and see how often it’s used! And be aware that these mirroring scenes don’t have to be the very first and very last scenes of the story: often the Full Circle moment comes at the beginning of Act III, or at the start of the Final Battle sequence. This method also works to let an audience or reader know we’re heading into the final stretch, which is always both an exciting and comforting thing for an audience.

We’ll talk more about great endings in the next chapter. But first, try a little brainstorming of your own.

> ASSIGNMENT: Take your list of top ten best endings of movies and books, and write down specifically, in detail, what it is about those endings that really does it for you.

> ASSIGNMENT: What is your hero/ine’s greatest nightmare? How can you bring that to life in your final battle scene?

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 14.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Okay!! It's the last week - we're into Act III, now! Or maybe, even probably, you're not that far yet, which is perfectly fine. As long as you're writing, it's all good. The book will be done when it's done.

But if you are into Act III, here are the prompts for that last act.

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

- Alex

ELEMENTS OF ACT THREE

Act Three is generally the final 20 to 30 minutes in a film, or the last 70 to 100 pages in a 400-page novel. The final quarter, and the shortest quarter.

It is often divided into these two major sequences:

1. Getting there (STORMING THE CASTLE)2. The FINAL BATTLE itself

Plus a shorter RESOLUTION/NEW WAY OF LIFE.

And it usually contains these elements:

• Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero/ine will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelation of the second act climax.• There may be a TICKING CLOCK• The Hero/ine may REASSEMBLE THE TEAM, and there may be another short TRAINING SEQUENCE and/or GATHERING THE TOOLS sequence• The team often goes in together, first, and there is a big ENSEMBLE BATTLE• In this battle, we possibly see the ALLY/ALLIES’ CHARACTER CHANGES and/or gaining of desire • We also get the DEFEAT OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS• Then the hero/ine goes into the FINAL BATTLE to face the antagonist alone, MANO A MANO• The final battle takes place in a THEMATIC LOCATION: often a visual and literal representation of the HERO/INE’S GREATEST NIGHTMARE, and is very often a metaphorical CASTLE. Or a real one! It is also often the antagonist’s home turf.• We see the protagonist’s character arc• We may see the antagonist’s character arc, too (but often there is none)• We get a glimpse of the TRUE NATURE OF THE ANTAGONIST• Possibly there is a huge FINAL REVERSAL or reveal (twist), or even a whole series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and It’s A Wonderful Life)• FULL CIRCLE: Not every story uses this, but often the hero/ine returns to a place we saw at the beginning of the story, and we see her or his character growth.• RESOLUTION: We get a glimpse into the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it• FINAL BOWS: We need to see all our favorite characters one final time• CLOSING IMAGE: Which is often a variation of the Opening ImageAll right, let’s look at these more closely.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist.

And sometimes that’s really all there is to it: one final battle between the protagonist and antagonist. In which case some good revelatory twists are probably required!

By the end of the second act, pretty much everything has been set up that we need to know — particularly who the antagonist is, which sometimes we haven’t known, or have been wrong about, until it’s revealed at the second act climax. Of course, sometimes, or maybe often, there is one final reveal about the antagonist that is saved till the very end or nearly the end, as in The Usual Suspects and The Empire Strikes Back and Psycho.

We also very often have gotten a sobering or terrifying glimpse of the TRUE NATURE OF THE ANTAGONIST — a great example of that kind of “nature of the opponent” scene is in Chinatown, in that scene in which Jake is slapping Evelyn and he learns the truth about her father.

There is often a new, FINAL PLAN that the hero/ine makes that takes into account the new information and revelations. As always with a plan, it’s good to spell it out.

There’s a locational aspect to the third act: the final battle will often take place in a completely different setting than the rest of the film or novel. In fact, half of the third act can be, and often is, just getting to the site of the final showdown. One of the most memorable examples of this in movie history is the STORMING THE CASTLE scene in The Wizard of Oz, where, led by an escaped Toto, the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion scale the cliff, scope out the vast armies of the witch (“Yo Ee O”) and tussle with three stragglers to steal their uniforms and march in through the drawbridge of the castle with the rest of the army (an example of a PLAN BY ALLIES). The Princess Bride also has a literal Storming the Castle scene, with the Billy Crystal and Carol Kane characters waving our team off shouting, “Have fun storming the castle!”

A sequence like this, and the similar ones in Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, can have a lot of the elements we discussed about the first half of the story: a PLAN, ASSEMBLING THE TEAM, ASSEMBLING TOOLS AND DISGUISES, TRAINING OR REHEARSAL.

I’m not just talking about action and fantasy movies, here. You see a truncated version of this team battle plan and storming the castle scene in Notting Hill, when all of Will’s friends pile into the car to help him catch Anna before she leaves.

And of course speed is often a factor — there’s may be a TICKING CLOCK, so our hero/ine has to race to get there in time to – save the innocent victim from the killer, save his or her kidnapped child from the kidnapper, stop the loved one from getting on that plane to Bermuda…

NO. DO NOT WRITE THAT LAST ONE.

Most clichéd film ending ever. Throw in the hero/ine getting stuck in a cab in Manhattan rush hour traffic and you really are risking audiences vomiting in the aisles, or readers, beside their chairs. This is in fact the most despised romantic comedy cliché on every single “Romantic Comedy Clichés” website out there.But when you think about it, the first two examples are equally clichéd. Sometimes there’s a fine line between clichéd and archetypal. You have to find how to elevate —or deepen — the clichéd to something archetypal.

Even if there’s not a literal castle, almost every story will have a metaphorical Storming the Castle element. The hero/ine usually must infiltrate the antagonist’s hideout, or castle, or lair, and confront the antagonist on his or her own turf, a terrifying and foreign place: think of Buffalo Bill’s basement in Silence of the Lambs, and the basement in Psycho, and the basement in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The castle can be a dragon’s lair (How to Train Your Dragon), or a dream fortress (Inception), or a church (a million romantic comedies).

Putting the final showdown on the villain’s turf means the villain has home-court advantage. The hero/ine has the extra burden of being a fish out of water in unfamiliar territory (mixing a metaphor to make it painfully clear).

I’ve noticed that in most films, there is a TEAM BATTLE first. The allies get to shine in this one: their strengths and weaknesses are tested, PLANTS are paid off, and allies who have been at each other’s throats for the whole story suddenly reconcile and work together. We also often get the DEFEAT OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS (if we’ve come to hate a secondary opponent, we need to see them get their comeuppance in a satisfying way — think of Fanny and Lucy Steele cat fighting each other in Sense and Sensibility, and Belloq, General Strasser, and Major Toht’s faces melting in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The TEAM BATTLE is generally a big, noisy SETPIECE scene.

And then, almost always, the hero/ine must go in to the FINAL BATTLE to face the antagonist alone, mano a mano.

So if this is the pattern we see over and over again, how can we possibly make it fresh?

Well, of course — look at books and films to see how your favorite storytellers do it.

Silence of the Lambs is a perfect example of elevating the cliché into archetype. The climax takes place in the basement, as it also does in Psycho, and Nightmare on Elm Street. This basement setting is no accident: therapists talk about “basement issues” —which are your worst fears and traumas from childhood — the stuff no one wants to look at, but which we have to look at, and clean out, to be whole.

But Thomas Harris, in the book, and the filmmakers, bringing it to life in the movie, create a basement that is so rich in horrific and revelatory and mythic (really fairy tale) imagery, that we never feel that we’ve seen that scene before. In fact I see new resonances in the set design every time I watch that film… like Mr. Gumb (Buffalo Bill) having a wall of news clippings just exactly like the one in Crawford’s office. That’s a technique that Harris uses that can elevate the clichéd to the archetypal: layering meaning.

But even more than that: Gumb’s basement is Clarice’s GREATEST NIGHTMAREcome to life. Lecter has exposed her deepest trauma, losing the lamb she tried to save from spring slaughter, and now she’s back in that childhood crisis, trying to save Catherine’s life (if you’ll notice, even the visual of Catherine clinging to Mr. Gumb’s fluffy white dog looks very much like a little girl holding a lamb…)

Nightmare on Elm Street takes that clichéd spooky basement scene and gives it a whole new level, literally: the heroine is dreaming that she is following a suspicious sound down into the basement, and then there’s a door that leads to another basement, under the basement. And if you think bad things happen in the basement, what’s going to happen in a sub-basement?

Comedy characters have a different kind of GREATEST NIGHTMARE.

Suppose you’re writing a farce. I would never dare, myself, but if I did, I would go straight to Fawlty Towers to figure out how to do it (and if you haven’t seen this brilliant TV series of John Cleese’s, I envy you the treat you’re in for). Every story in this series shows the quintessentially British Basil Fawlty go from rigid control to total breakdown of order in the side-splitting climax. It is the vast chasm between Basil’s idea of what his life should be and the chaotic reality that he creates for himself over and over again that will have you screaming with laughter.

Another very technical lesson to take from Fawlty Towers —and from any screwball comedy or farce — is how comedies use speed in climax. Just as in other forms of climax, the action speeds up in the end, to create that exhilaration of being out of control — which is the sensation I most love about a great comedy.

In a romance, the Final Battle is often the hero/ine finally overcoming his or her internal blocks and making a DECLARATIONor PROPOSAL to the loved one. And I’ve noticed that a lot of romances do the declaration in a one-two punch, two separate scenes: the recalcitrant lover makes his or her declaration, even does some groveling, apparently to no avail, and only in a later, final scene does the loved one show up with a declaration of his or her own.

An archetypal setting for the Final Battle in romantic comedy is an actual wedding. We’ve seen this scene so often you’d think there’s nothing new you can do with it. But of course a story about love and relationships is likely to end at a wedding.

So again, if you’re writing this kind of story, make your list and look at what great romantic comedies have done to elevate the cliché.

One of my favorite romantic comedies of all time, The Philadelphia Story, uses a classic technique to keep that wedding sequence sparkling: every single one of that large ensemble of characters has her or his own wickedly delightful resolution. Everyone has their moment to shine, and insanely precocious little sister Dinah pretty nearly steals the show (from Katharine Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant!!) with her last line: “I did it. I did it all.”

(This is a good lesson for any ensemble story, no matter what genre — all the characters should constantly be competing for the spotlight, just as in any good theater troupe. Make your characters divas and scene-stealers and let them top each other.)

Now, you see a completely different kind of final battle in It’s A Wonderful Life. This is not the classic, “hero confronts villain on villain’s home turf” third act. In fact, Potter is nowhere around in the final confrontation, is he? There’s no showdown, even though we desperately want one.

But the point of that story is that George Bailey has been fighting Potter all along.

There is no big glorious heroic showdown to be had, here, because it’s all the little grueling day-to-day, crazymaking battles that George has had with Potter all his life that have made the difference. And the genius of that film is that it shows in vivid and disturbing detail what would have happened if George had not had that whole lifetime of battles, against Potter and for the town. In the end, even faced with prison, George makes the choice to live to fight another day, and is rewarded with the joy of seeing his town restored.

This is the best example I know of, ever, of a final battle that is thematic — and yet the impact is emotional and visceral. It’s not an intellectual treatise; you live that ending along with George, but also come away with the sense of what true heroism is.

And the wonderful final battle in The King’s Speech is just Colin Firth facing a microphone and delivering a nine-minute radio broadcast. But we’ve seen him fail this moment because of his speech impediment time and time again in SET UPS; and this time the STAKES couldn’t be higher: it’s his first radio broadcast as King, and he has to convince his already war-weary country to support a war against Hitler.

So when you sit down to craft your own third act, try looking at the great third acts of movies and books that are similar to your own story, and see what those authors and filmmakers did to bring out the thematic depth and emotional impact of their stories (We’ll be doing more of that in the next chapter, too.)

RESOLUTION AND NEW WAY OF LIFE

After the final battle is fought and won, we want to get a sense of the NEW LIFE the hero/ine is going to lead now that they’ve been through this incredible journey.

One of the greatest images of a NEW WAY OF LIFE ever put on film is from Romancing the Stone: the yacht parked in the Manhattan street outside Joan Wilder’s building, and Jack standing on deck waiting for her, with those alligator boots on. It’s a complete PAYOFF of his and her DESIRE lines (and the alligator boots are a great light touch that keeps it all from being too sugary), and a clear indication of what their life is going to be like from now on. Would this have worked as well if that yacht were in a harbor? No way. It’s the extravagance and quirkiness of the gesture that makes it so grandly romantic. It never fails to spike my endorphins, and that’s what these endings are all about.

FULL CIRCLE

Not all stories use this technique, but very, very often at the end of the story the hero/ine returns to the setting of the beginning. And often storytellers use a visual contrast in how that setting appears in the beginning and the end, to show the protagonist’s change in character or attitude.

In the beginning of The Godfather, Don Corleone is in his study, sitting behind his desk in a chair that looks like a throne, holding court and deciding the fates of his supplicants. In the final moments of the story, Michael Corleone stands at that same desk with his subordinates kissing his ring: he has become the Godfather. Early on in Act I of Romancing the Stone, pathologically shy Joan Wilder attempts to leave her apartment and is immediately set upon by street vendors, and we see how incapable she is of handling people and life in general. In Act III, she has returned from her adventure a changed woman, and we see her walking down that same street in her full Kathleen Turner goddesslike radiance, waving off those same street vendors both regally and casually.

You don’t have to use this Full Circle technique, but it can work well to bookend a story and depict CHARACTER ARC. Start to look for it in movies and see how often it’s used! And be aware that these mirroring scenes don’t have to be the very first and very last scenes of the story: often the Full Circle moment comes at the beginning of Act III, or at the start of the Final Battle sequence. This method also works to let an audience or reader know we’re heading into the final stretch, which is always both an exciting and comforting thing for an audience.

We’ll talk more about great endings in the next chapter. But first, try a little brainstorming of your own.

> ASSIGNMENT: Take your list of top ten best endings of movies and books, and write down specifically, in detail, what it is about those endings that really does it for you.

> ASSIGNMENT: What is your hero/ine’s greatest nightmare? How can you bring that to life in your final battle scene?

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 14.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $14.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

---------------------

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 28, 2018 07:01

November 26, 2018

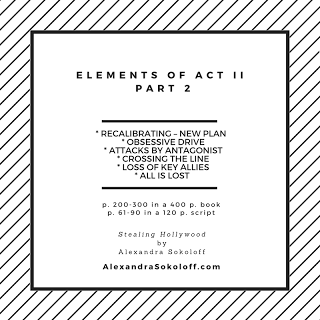

Nanowrimo: Elements of Act II: Part 2

by Alexandra Sokoloff

While I am moving on to prompts for the second half of Act Two, remember that wherever you are in this process is just fine. Personally I think it would be a little crazy to be into the second half of the second act in just three weeks!

So if you're not this far, just save this post for later.

If you're new to this blog, start here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

A few general things about Act II, Part 2. This is almost always the darkest quarter of the story. While in Act II, Part 1, the hero/ine is generally (but not always) winning, after the Midpoint, the hero/ine starts to lose, and lose big. And also lose very fast. In fact, this is the quarter that is most often shortened if you are writing a shorter book or movie, because it's not all that hard and doesn't take all that much time to pull the rug out from your protagonist.

Just knowing that basic, very general distinction between the two halves of Act Two can be very, very useful.

But getting more specific...

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

Act II, Part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud.

How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

- Alex

=====================================================

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $13.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

While I am moving on to prompts for the second half of Act Two, remember that wherever you are in this process is just fine. Personally I think it would be a little crazy to be into the second half of the second act in just three weeks!

So if you're not this far, just save this post for later.

If you're new to this blog, start here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

A few general things about Act II, Part 2. This is almost always the darkest quarter of the story. While in Act II, Part 1, the hero/ine is generally (but not always) winning, after the Midpoint, the hero/ine starts to lose, and lose big. And also lose very fast. In fact, this is the quarter that is most often shortened if you are writing a shorter book or movie, because it's not all that hard and doesn't take all that much time to pull the rug out from your protagonist.

Just knowing that basic, very general distinction between the two halves of Act Two can be very, very useful.

But getting more specific...

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

Act II, Part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud.

How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

- Alex

=====================================================

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $13.99 STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

You can also sign up to get free movie breakdowns here:

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 26, 2018 01:12

November 13, 2018

New book! - Hollywood vs. the Author

I’m psyched to announce that I have an essay in Hollywood vs. the Author , out today.

Hollywood vs. the Author

Hollywood vs. the AuthorIt’s (almost) every author’s dream to sell their book or series to Hollywood. But most know very little about the actual process, despite the vague and slightly terrifying rumors—which authors tend to ignore as exaggerations, too completely absurd to be real.

Hah.

My friend Stephen Jay Schwartz, former Director of Development for Wolfgang Peterson, has assembled a great list of authors who have sold books to Hollywood, authors who have worked as screenwriters, showrunners, TV producers, and authors who have written movie tie-ins.

My own essay, A Woman Wouldn’t Do That, recounts some of the surreal experiences I had in development hell during my ten years as a working screenwriter—before I snapped and wrote my first novel. I compare the two jobs – screenwriting vs. writing books— and talk about how I came full circle, back to Hollywood, once I had written a successful novel series that was a natural for the fantastic new age of television we’re in.

The Huntress Moon series

There’s a lot to learn here, from Michael Connelly’s harrowing experience with fine print (and how he triumphed over it, by betting on himself with Bosch), to Larry Block’s hilarious recount of the vagaries of casting, to Tess Gerritsen’s heartbreaking and timely reminder that a bad judge makes bad judgments—that we all have to live with.

The Huntress Moon series

There’s a lot to learn here, from Michael Connelly’s harrowing experience with fine print (and how he triumphed over it, by betting on himself with Bosch), to Larry Block’s hilarious recount of the vagaries of casting, to Tess Gerritsen’s heartbreaking and timely reminder that a bad judge makes bad judgments—that we all have to live with.Between us all, we cover the good, the bad, the horrific, and the flat-out unbelievable.

And the audiobook, out December 5, is really a treat - it's read by all of the authors, ourselves!

So if selling your book to Hollywood is your dream, you owe it to yourself to check out these valuable lessons before you sign on that dotted line.

Check it out here!

Stephen Jay Schwartz, editor, with essays by Lawrence Block, Michael Connelly, Gregg Hurwitz, Andrew Kaplan, Tess Gerritsen, Diana Gould, Lee Goldberg, James Brown, Alexandra Sokoloff, Ron Roberge, T. Jefferson Parker, Alan Jacobson, Max Allan Collins, Peter James, Naomi Hirahara, and Joshua Corin – plus an interview with Jonathan Kellerman.

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> -->

Published on November 13, 2018 03:01

November 12, 2018

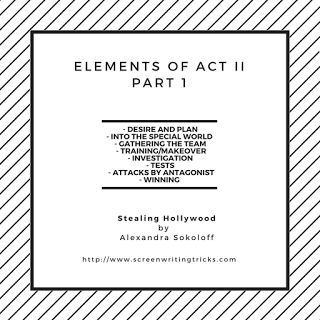

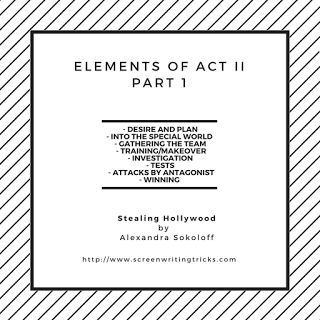

Nanowrimo: Act Two, Part 1 questions and prompts

ACT TWO, PART ONE

by Alexandra Sokoloff, from STEALING HOLLYWOOD: Screenwriting Tricks for Authors

(Elements of Act I checklist is here).

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 400-page book Act II, Part 1 starts at about p. 100 and climaxes at about p. 200.

Act II, Part 1 is the most variable section of the four sections of a story. I have noticed it also tends to be the most genre-specific. It doesn’t have the very clear, generic essential elements that Act I and Act III do – except in the case of Mysteries and certain kinds of team action films, which generally have a more standard structure in this section.

IF THE FILM IS A MYSTERY, this section will almost always have these elements:

-QUESTIONING WITNESSES

-LINING UP AND ELIMINATING SUSPECTS

-FOLLOWING CLUES

-RED HERRINGS AND FALSE TRAILS

-THE DETECTIVE VOICING HER/HIS THEORY

IF THE FILM IS A TEAM ACTION STORY, A WAR STORY, A HEIST OR CAPER MOVIE (like OCEAN’S 11, THE SEVEN SAMURI, THE DIRTY DOZEN, ARMAGGEDON and INCEPTION) then this section will usually have these elements:

- GATHERING THE TEAM

- TRAINING SEQUENCE

- GATHERING THE TOOLS

- BONDING BETWEEN TEAM MEMBERS

- SETTING UP TEAM MEMBERS’ STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES that will be tested in battle later.

There may also be

- A MACGUFFIN

- A TICKING CLOCK

But if the story is not a mystery or a team action story, the first half of Act 2 will often have some of the above elements, and ALL stories will generally have these next elements in Act II, part 1 (not in any particular order):

- CROSSING THE THRESHOLD - ENTERING THE SPECIAL WORLD

(This scene may already have happened in Act One, but it often happens right at the end of Act One or right at the beginning of Act Two.) How do the storytellers make this moment important? Is there a special PASSAGEWAY between the worlds?

- THRESHOLD GUARDIAN (maybe)

There is very often a character who tries to prevent the hero/ine from entering the SPECIAL WORLD, or who gives them a warning about danger.

- HERO/INE’S PLAN

- What is the hero/ine’s PLAN to get what s/he wants?

The plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the hero/ine start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail.

- THE ANTAGONIST’S PLAN

Same as for the hero/ine: the plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the villain start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail. Even if the villain is being kept secret, we will see the effects of the villain's plan on the hero/ine.

- ATTACKS AND COUNTERATTACKS

How do we see the antagonist attacking the hero/ine?

Whether or not the hero/ine realizes who is attacking her or him, the antagonist (s) will be nearby and constantly attacking the hero/ine. How does the hero/ine fight back?

- SERIES OF TESTS

How do we see the hero/ine being tested?

In a mentor story, the mentor will often be designing these tests, and there may be a training sequence or training scenes as well. Sometimes (as in THE GODFATHER) no one is really designing the tests, but the hero/ine keeps running up against obstacles to what they want and they have to overcome those obstacles, and with each win they become stronger.

- OFTEN THE HERO/INE IS WINNING

The hero/ine usually wins a lot in Act II:1 (and then starts to lose throughout Act II:2), but that’s not necessarily true. In JAWS, Sheriff Brody doesn’t get a win until the big defeat of the Midpoint, when he is finally able to force the mayor to sign a check and hire Quint to kill the shark.

- BONDING WITH ALLIES – LOVE SCENES

This is one of the great pleasures of any story – seeing the hero/ine make lifelong friends or fall in love. Besides the more obvious romantic scenes, the love scenes can be between a boy and his dragon, as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON; or between teammates, as in JAWS; or a man and his father or a woman and her mother (some of the most successful movies, like THE GODFATHER, HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, TERMS OF ENDEARMENT and STEEL MAGNOLIAS show these dynamics). What are the scenes that make us feel the glow of love or joy of friendship?

Or in darker stories, instead of bonding scenes, the storytellers may show the hero/ine pulling away from people and becoming more and more alienated, as in THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, THE SHINING, CASINO.

In a love story, there is always a specific scene that you might call THE DANCE, where we see for the first time that the two lovers are perfect for each other (this is often some witty exchange of dialogue when the two seem to be finishing each other’s sentences, or maybe they end up forced to sing karaoke together and bring down the house…). You see this Dance scene in buddy comedies and buddy action movies as well.

- GENRE SCENES (action, horror, suspense, sex, emotion, adventure, violence)

Act II, part 1 is the section of a story that will really deliver on THE PROMISE OF THE PREMISE.

What is the EXPERIENCE that you hope and expect to get from this story? – is it the glow and sexiness of falling in love, or the adrenaline rush of supernatural horror, or the intellectual pleasure of solving a mystery, or the vicarious triumph of kicking the ass of a hated enemy in hand-to-hand combat?

Here are some examples:

- In THE GODFATHER, we get the EXPERIENCE of Michael gaining in power as he steps into the family business. There’s a vicarious thrill in seeing him win these battles.

- In JAWS, we EXPERIENCE the terror of what it’s like to be in a small beach town under attack by a monster of the sea.

- In HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, we get the EXPERIENCE and wonder of discovering all these cool and endearing qualities about dragons, including and especially the EXPERIENCE of flying. We also get to EXPERIENCE outcast and loser Hiccup suddenly winning big in the training ring.

- In HARRY POTTER (1), we get the EXPERIENCE of going to a school for wizards and learning and practicing magic (including flying).

(I want to note that for those of you working with horror stories, it’s very important to identify WHAT IS THE HORROR, exactly? What are we so scared of, in this story? How do the storytellers give us the experience of that horror?)

Ask yourself what EXPERIENCE you want your audience or reader to have in your own story, then look for the scenes that deliver on that promise in Act II, part 1. Well, do they? If not, how can you enhance that experience?

And another big but important generalization I can make about Act II, part 1, is that this is often where the specific structure of the KIND of story you’re writing (or viewing) kicks in. For more on identifying KINDS of stories, see What Kind Of Story Is It?

Act II part 1 builds to the MIDPOINT CLIMAX – which in movies is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 15.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $15.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon US

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

by Alexandra Sokoloff, from STEALING HOLLYWOOD: Screenwriting Tricks for Authors

(Elements of Act I checklist is here).

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.In a 400-page book Act II, Part 1 starts at about p. 100 and climaxes at about p. 200.

Act II, Part 1 is the most variable section of the four sections of a story. I have noticed it also tends to be the most genre-specific. It doesn’t have the very clear, generic essential elements that Act I and Act III do – except in the case of Mysteries and certain kinds of team action films, which generally have a more standard structure in this section.

IF THE FILM IS A MYSTERY, this section will almost always have these elements:

-QUESTIONING WITNESSES

-LINING UP AND ELIMINATING SUSPECTS

-FOLLOWING CLUES

-RED HERRINGS AND FALSE TRAILS

-THE DETECTIVE VOICING HER/HIS THEORY

IF THE FILM IS A TEAM ACTION STORY, A WAR STORY, A HEIST OR CAPER MOVIE (like OCEAN’S 11, THE SEVEN SAMURI, THE DIRTY DOZEN, ARMAGGEDON and INCEPTION) then this section will usually have these elements:

- GATHERING THE TEAM

- TRAINING SEQUENCE

- GATHERING THE TOOLS

- BONDING BETWEEN TEAM MEMBERS

- SETTING UP TEAM MEMBERS’ STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES that will be tested in battle later.

There may also be

- A MACGUFFIN

- A TICKING CLOCK

But if the story is not a mystery or a team action story, the first half of Act 2 will often have some of the above elements, and ALL stories will generally have these next elements in Act II, part 1 (not in any particular order):

- CROSSING THE THRESHOLD - ENTERING THE SPECIAL WORLD

(This scene may already have happened in Act One, but it often happens right at the end of Act One or right at the beginning of Act Two.) How do the storytellers make this moment important? Is there a special PASSAGEWAY between the worlds?

- THRESHOLD GUARDIAN (maybe)

There is very often a character who tries to prevent the hero/ine from entering the SPECIAL WORLD, or who gives them a warning about danger.

- HERO/INE’S PLAN

- What is the hero/ine’s PLAN to get what s/he wants?

The plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the hero/ine start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail.

- THE ANTAGONIST’S PLAN

Same as for the hero/ine: the plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the villain start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail. Even if the villain is being kept secret, we will see the effects of the villain's plan on the hero/ine.

- ATTACKS AND COUNTERATTACKS

How do we see the antagonist attacking the hero/ine?

Whether or not the hero/ine realizes who is attacking her or him, the antagonist (s) will be nearby and constantly attacking the hero/ine. How does the hero/ine fight back?

- SERIES OF TESTS

How do we see the hero/ine being tested?

In a mentor story, the mentor will often be designing these tests, and there may be a training sequence or training scenes as well. Sometimes (as in THE GODFATHER) no one is really designing the tests, but the hero/ine keeps running up against obstacles to what they want and they have to overcome those obstacles, and with each win they become stronger.

- OFTEN THE HERO/INE IS WINNING

The hero/ine usually wins a lot in Act II:1 (and then starts to lose throughout Act II:2), but that’s not necessarily true. In JAWS, Sheriff Brody doesn’t get a win until the big defeat of the Midpoint, when he is finally able to force the mayor to sign a check and hire Quint to kill the shark.

- BONDING WITH ALLIES – LOVE SCENES

This is one of the great pleasures of any story – seeing the hero/ine make lifelong friends or fall in love. Besides the more obvious romantic scenes, the love scenes can be between a boy and his dragon, as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON; or between teammates, as in JAWS; or a man and his father or a woman and her mother (some of the most successful movies, like THE GODFATHER, HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, TERMS OF ENDEARMENT and STEEL MAGNOLIAS show these dynamics). What are the scenes that make us feel the glow of love or joy of friendship?

Or in darker stories, instead of bonding scenes, the storytellers may show the hero/ine pulling away from people and becoming more and more alienated, as in THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, THE SHINING, CASINO.

In a love story, there is always a specific scene that you might call THE DANCE, where we see for the first time that the two lovers are perfect for each other (this is often some witty exchange of dialogue when the two seem to be finishing each other’s sentences, or maybe they end up forced to sing karaoke together and bring down the house…). You see this Dance scene in buddy comedies and buddy action movies as well.

- GENRE SCENES (action, horror, suspense, sex, emotion, adventure, violence)

Act II, part 1 is the section of a story that will really deliver on THE PROMISE OF THE PREMISE.

What is the EXPERIENCE that you hope and expect to get from this story? – is it the glow and sexiness of falling in love, or the adrenaline rush of supernatural horror, or the intellectual pleasure of solving a mystery, or the vicarious triumph of kicking the ass of a hated enemy in hand-to-hand combat?

Here are some examples:

- In THE GODFATHER, we get the EXPERIENCE of Michael gaining in power as he steps into the family business. There’s a vicarious thrill in seeing him win these battles.

- In JAWS, we EXPERIENCE the terror of what it’s like to be in a small beach town under attack by a monster of the sea.

- In HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, we get the EXPERIENCE and wonder of discovering all these cool and endearing qualities about dragons, including and especially the EXPERIENCE of flying. We also get to EXPERIENCE outcast and loser Hiccup suddenly winning big in the training ring.

- In HARRY POTTER (1), we get the EXPERIENCE of going to a school for wizards and learning and practicing magic (including flying).

(I want to note that for those of you working with horror stories, it’s very important to identify WHAT IS THE HORROR, exactly? What are we so scared of, in this story? How do the storytellers give us the experience of that horror?)

Ask yourself what EXPERIENCE you want your audience or reader to have in your own story, then look for the scenes that deliver on that promise in Act II, part 1. Well, do they? If not, how can you enhance that experience?

And another big but important generalization I can make about Act II, part 1, is that this is often where the specific structure of the KIND of story you’re writing (or viewing) kicks in. For more on identifying KINDS of stories, see What Kind Of Story Is It?

Act II part 1 builds to the MIDPOINT CLIMAX – which in movies is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

=====================================================

All the information on this blog and more, including full story structure breakdowns of various movies, is available in my Screenwriting Tricks for Authors workbooks. e format, just $3.99 and $2.99; print 15.99.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD

This new workbook updates all the text in the first Screenwriting Tricks for Authors ebook with all the many tricks I’ve learned over my last few years of writing and teaching—and doubles the material of the first book, as well as adding six more full story breakdowns.

STEALING HOLLYWOOD ebook $3.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD US print $15.99

STEALING HOLLYWOOD print, all countries

WRITING LOVE

Writing Love is a shorter version of the workbook, using examples from love stories, romantic suspense, and romantic comedy - available in e formats for just $2.99.

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon US

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

Published on November 12, 2018 09:46

Nanowrimo: Act Two questions and prompts

ACT TWO, PART ONE

by Alexandra Sokoloff, from STEALING HOLLYWOOD: Screenwriting Tricks for Authors

(Elements of Act I checklist is here).

Get free Story Structure extras and movie breakdowns

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 2-hour movie Act II, Part 1 starts at about 30 minutes, and ends at about 60 minutes.

In a 400-page book Act II, Part 1 starts at about p. 100 and climaxes at about p. 200.

Act II, Part 1 is the most variable section of the four sections of a story. I have noticed it also tends to be the most genre-specific. It doesn’t have the very clear, generic essential elements that Act I and Act III do – except in the case of Mysteries and certain kinds of team action films, which generally have a more standard structure in this section.

IF THE FILM IS A MYSTERY, this section will almost always have these elements:

-QUESTIONING WITNESSES

-LINING UP AND ELIMINATING SUSPECTS

-FOLLOWING CLUES

-RED HERRINGS AND FALSE TRAILS

-THE DETECTIVE VOICING HER/HIS THEORY

IF THE FILM IS A TEAM ACTION STORY, A WAR STORY, A HEIST OR CAPER MOVIE (like OCEAN’S 11, THE SEVEN SAMURI, THE DIRTY DOZEN, ARMAGGEDON and INCEPTION) then this section will usually have these elements:

- GATHERING THE TEAM

- TRAINING SEQUENCE

- GATHERING THE TOOLS

- BONDING BETWEEN TEAM MEMBERS

- SETTING UP TEAM MEMBERS’ STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES that will be tested in battle later.

There may also be

- A MACGUFFIN

- A TICKING CLOCK

But if the story is not a mystery or a team action story, the first half of Act 2 will often have some of the above elements, and ALL stories will generally have these next elements in Act II, part 1 (not in any particular order):

- CROSSING THE THRESHOLD - ENTERING THE SPECIAL WORLD

(This scene may already have happened in Act One, but it often happens right at the end of Act One or right at the beginning of Act Two.) How do the storytellers make this moment important? Is there a special PASSAGEWAY between the worlds?

- THRESHOLD GUARDIAN (maybe)

There is very often a character who tries to prevent the hero/ine from entering the SPECIAL WORLD, or who gives them a warning about danger.

- HERO/INE’S PLAN

- What is the hero/ine’s PLAN to get what s/he wants?

The plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the hero/ine start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail.

- THE ANTAGONIST’S PLAN

Same as for the hero/ine: the plan may have been stated in Act I, but here is where we see the villain start to act on the plan, and often s/he will have to keep changing the plan as early attempts fail. Even if the villain is being kept secret, we will see the effects of the villain's plan on the hero/ine.

- ATTACKS AND COUNTERATTACKS

How do we see the antagonist attacking the hero/ine?

Whether or not the hero/ine realizes who is attacking her or him, the antagonist (s) will be nearby and constantly attacking the hero/ine. How does the hero/ine fight back?

- SERIES OF TESTS

How do we see the hero/ine being tested?

In a mentor story, the mentor will often be designing these tests, and there may be a training sequence or training scenes as well. Sometimes (as in THE GODFATHER) no one is really designing the tests, but the hero/ine keeps running up against obstacles to what they want and they have to overcome those obstacles, and with each win they become stronger.

- OFTEN THE HERO/INE IS WINNING

The hero/ine usually wins a lot in Act II:1 (and then starts to lose throughout Act II:2), but that’s not necessarily true. In JAWS, Sheriff Brody doesn’t get a win until the big defeat of the Midpoint, when he is finally able to force the mayor to sign a check and hire Quint to kill the shark.

- BONDING WITH ALLIES – LOVE SCENES

This is one of the great pleasures of any story – seeing the hero/ine make lifelong friends or fall in love. Besides the more obvious romantic scenes, the love scenes can be between a boy and his dragon, as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON; or between teammates, as in JAWS; or a man and his father or a woman and her mother (some of the most successful movies, like THE GODFATHER, HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, TERMS OF ENDEARMENT and STEEL MAGNOLIAS show these dynamics). What are the scenes that make us feel the glow of love or joy of friendship?

Or in darker stories, instead of bonding scenes, the storytellers may show the hero/ine pulling away from people and becoming more and more alienated, as in THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, THE SHINING, CASINO.

In a love story, there is always a specific scene that you might call THE DANCE, where we see for the first time that the two lovers are perfect for each other (this is often some witty exchange of dialogue when the two seem to be finishing each other’s sentences, or maybe they end up forced to sing karaoke together and bring down the house…). You see this Dance scene in buddy comedies and buddy action movies as well.

- GENRE SCENES (action, horror, suspense, sex, emotion, adventure, violence)

Act II, part 1 is the section of a story that will really deliver on THE PROMISE OF THE PREMISE.

What is the EXPERIENCE that you hope and expect to get from this story? – is it the glow and sexiness of falling in love, or the adrenaline rush of supernatural horror, or the intellectual pleasure of solving a mystery, or the vicarious triumph of kicking the ass of a hated enemy in hand-to-hand combat?

Here are some examples:

- In THE GODFATHER, we get the EXPERIENCE of Michael gaining in power as he steps into the family business. There’s a vicarious thrill in seeing him win these battles.

- In JAWS, we EXPERIENCE the terror of what it’s like to be in a small beach town under attack by a monster of the sea.

- In HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON, we get the EXPERIENCE and wonder of discovering all these cool and endearing qualities about dragons, including and especially the EXPERIENCE of flying. We also get to EXPERIENCE outcast and loser Hiccup suddenly winning big in the training ring.

- In HARRY POTTER (1), we get the EXPERIENCE of going to a school for wizards and learning and practicing magic (including flying).

(I want to note that for those of you working with horror stories, it’s very important to identify WHAT IS THE HORROR, exactly? What are we so scared of, in this story? How do the storytellers give us the experience of that horror?)

Ask yourself what EXPERIENCE you want your audience or reader to have in your own story, then look for the scenes that deliver on that promise in Act II, part 1. Well, do they? If not, how can you enhance that experience?

And another big but important generalization I can make about Act II, part 1, is that this is often where the specific structure of the KIND of story you’re writing (or viewing) kicks in. For more on identifying KINDS of stories, see What Kind Of Story Is It?

Act II part 1 builds to the MIDPOINT CLIMAX – which in movies is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win