Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 533

March 14, 2012

Warn people about two things

One problem with disclosure regulation is that people grow accustomed to the warnings and caveats and their eyes glaze over. They stop paying attention.

So let's say you are the Über-regulator. You get to warn people about two things. Once.

Of course they may not listen to you at all, but let's assume you have enough credibility from your political post to be given half an hour on network TV and subsequent extensive coverage and commentary on blogs and Twitter. That said, especially useful warnings, such as "You're not as smart as you think" are perhaps especially likely to be ignored. "Honor They Superior!" is perhaps also a non-starter, though you may try it if you wish.

Which two things do you pick for your warning?

"Driving is dangerous"

"Fight nuclear proliferation."

"Don't let your kid near a bucket."

"Politics isn't about policy."

"Beware the Ides of March!"

"Some people out there suck!"

The correct answer is not obvious. And what does this imply about regulation more generally?

I thank Bryan Caplan for a useful conversation on this topic.

Black market Tide free banking

The Daily's M.L. Nestel cites law enforcement reports from across America describing a crime-wave of Tide detergent thefts, including claims that bottles of easily resellable, name-brand washing soap can be bartered for meth and heroin in Gresham, OR.

He cites this article:

Tide has become a form of currency on the streets. The retail price is steadily high — roughly $10 to $20 a bottle — and it's a staple in households across socioeconomic classes.

Tide can go for $5 to $10 a bottle on the black market, authorities say. Enterprising laundry soap peddlers even resell bottles to stores.

"There's no serial numbers and it's impossible to track," said Detective Larry Patterson of the Somerset, Ky., Police Department, where authorities have seen a huge spike in Tide theft. "It's the item to steal."

Why Tide and not, say, Wisk or All? Police say it's simply because the Procter & Gamble detergent is the most popular and, with its Day-Glo orange logo, most recognizable of brands.

For the pointer I thank Ken Feinstein and Pamela J. Stubbart.

March 13, 2012

The taco truck mystery

This one comes from Felix Salmon. In my view Felix puts forward the two correct hypotheses:

…food trucks are much more likely to be run by first-generation immigrants, for a variety of reasons. Quite aside from any hard-working immigrant stereotype, that's good news just because the food they sell is going to be that much more authentic. (Not that food trucks need to be particularly authentic to be delicious: just ask the Korean taco people.)

And:

My favorite theory is that it basically comes down to the amount of time that elapses between the taco being made and the taco being eaten. Fillings can stay warm and delicious for a while, but the tortilla really is at its very best within seconds of coming off the stove, rather than getting soggy at the bottom of a tortilla warmer brought to you by your server. I suspect that if you could walk into the kitchen of a decent taco restaurant and get the chef to make you one then and there, it too would taste better than the same taco ordered off the menu.

I would add one factor. Taco trucks are mobile, and they often serve Latino construction workers, who are themselves mobile in terms of choosing various workplaces over the course of a year, and thus they require mobile sources of food. This encourages the taco truck, but not the stationary restaurant, to invest in better and more authentic food.

Assorted links

2. Who's afraid of development?

3. The world's fastest reader?

4. Markets in everything homeless hot spots.

5. Economic origins of the Sicilian Mafia.

6. A new study of RomneyCare and health outcomes. I have yet to read the paper.

Middle East facts of the day

…according to the United States Census Bureau, Iran now has a similar birth rate to New England — which is the least fertile region in the U.S.

The speed of the change is breathtaking. A woman in Oman today has 5.6 fewer babies than a woman in Oman 30 years ago. Morocco, Syria and Saudi Arabia have seen fertility-rate declines of nearly 60 percent, and in Iran it's more than 70 percent. These are among the fastest declines in recorded history.

That is from David Brooks. These societies will be old before they will be wealthy. Which means perhaps they will never be wealthy.

What is up with the gdp-less recovery?

That is what people are calling it, although I would not use that term. Jon Hilsenrath has the best overview I have seen, here is one excerpt:

Robert Gordon, a Northwestern University professor who tracks productivity closely, says he sees "clear signs everywhere" that a productivity slowdown is happening. Last year, productivity—measured as the output of workers for every hour they work—grew just 0.4% and has grown at a 0.9% annual rate over the past seven quarters. Productivity did spurt higher in 2009—during this stretch of fear-induced firing—but over a longer stretch it shows additional signs of slowing. Worker productivity has grown at an annual rate of 1.7% since 2004, down from 2.6% growth in the decade before that.

Mr. Gordon agrees with Ms. Romer's overfiring story. But he says the longer-run threat to productivity shouldn't be overlooked. "The productivity numbers have been dismal," he says. That is an explanation this fragile economy can do without and that policy makers shouldn't ignore.

I don't myself see an additional short-run fall in productivity (I don't much trust the short-run statistics in any case), though of course I have been a productivity pessimist more generally.

First and foremost, I see the very latest data as evidence for the Garett Jones hypothesis. Employers are going back to the idea of investing in workers who build up the future of the company, but who may not produce much output now.

Second, higher exports and moderating health care costs (the latter over the last two years) mean that "real gdp" is higher than traditionally measured gdp; see for instance Matt's remarks. This supports Michael Mandel's view about the importance of offshoring and, presumably, reshoring, to the extent that is going on. In general we undermeasure the gdp gains of successful export nations, because their outputs tend to have lower percentages of rent-seeking expenditures and more real stuff of value.

Karl Smith has interesting posts on related questions. Scott Sumner wrote an early and important post on the same topic. His bottom line was this:

So what are the likely explanations?

1. Trend growth really is slowing somewhat.

2. People are leaving the labor force.

3. RGDP data is measuring "payroll GDP," not household GDP

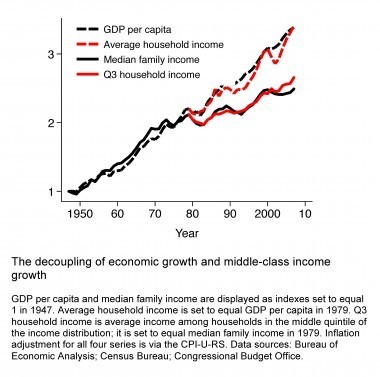

Counting benefits does not much change the income stagnation story

Lane Kenworthy reports:

A third worry is that the income measure used to calculate median family income is too thin. If a growing portion of GDP has gone to employer benefits, that would help middle-class households, but it wouldn't show up in these income data.

To address these second and third concerns, we can turn to a more encompassing measure of household income. The data are from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The measure includes all sources of cash income. It adds in-kind income (employer-paid health insurance premiums, food stamps, Medicare and Medicaid benefits), employee contributions to 401(k) retirement plans, and employer-paid payroll taxes. Tax payments are subtracted.

We can use average household income in these data as a substitute for GDP per capita. The CBO data set doesn't tell us the median income, but it provides something quite similar: the average income of households in the middle quintile of the distribution (from the 40th percentile to the 60th). The following chart adds these two series. The story is virtually identical.

He considers some other adjustments too, and this is the final story:

March 12, 2012

What is the real source of the medical adverse selection problem?

Ray Fisman reports on the job market paper of Nathaniel Hendren, an MIT student on the job market this year. Here is an excerpt from Fisman's piece:

…sufferers of heart disease and cancer have greater self-knowledge than healthy people in terms of what their likely medical care costs will be. The market for insurance unravels, in Hendren's model, when patients have a clear view of their future health care costs and people who anticipate lower-cost futures self-select out of insurance coverage.

It's not about knowing more about your state of health, it is about knowing more about how costly your treatment will be.

Assorted links

1. Crossword robots.

2. American exports to China boom.

3. No NIMBY from these people.

4. Rushdie on the eBook lawsuit, and here two experts debate the same.

5. A clothing tag, and Henry and Quiggin on Keynesianism in the Great Recession.

The French election campaign continues

Sarkozy struck a strident new tone in a Sunday rally.

He threatened to pull France out of the Schengen open borders agreement and demanded the European Union adopt measures to fight cheap imports, warning that France might otherwise pass a unilateral "Buy French" law.

"I want a Europe that protects its citizens. I no longer want this savage competition," he declared to a cheering crowd. "I have lost none of my will to act, my will to make things change, my belief in the genius of France."

The story is here.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers