Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 510

May 16, 2012

How emigrants try to run their fiscal policies

In survey data collected as part of the study, Washington, D.C.–based migrants from El Salvador report that they would like recipient households to save 21.2 percent of remittance receipts, while recipient households prefer to save only 2.6 percent of receipts.

This is one reason why emigrant workers do not send more back home all at once, namely that the sender does some ex ante forced saving on behalf of the recipient, who otherwise is not trusted to do it. Remitters also send relatively small sums — typical is $300 — but they send many times a year (16.9 times on average, in one study, despite some fixed costs of sending). That is to stop the recipient from spending all of the aid at once.

Perhaps you have noticed that cross-national and multilateral aid is also often doled out in multiple parts, rather than all at once.

Is this socially optimal? Maybe not. Is this nearly universal? Possibly so.

The quotation is from Dean Yang, here is more (pdf, see p.12).

May 15, 2012

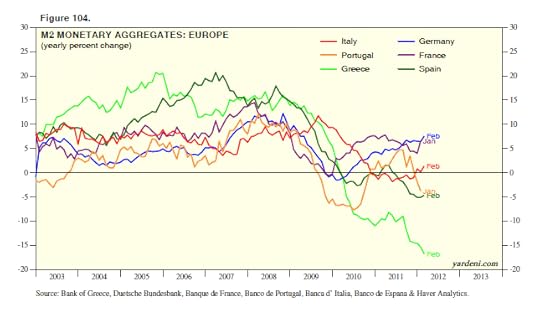

I know, I know, M2 isn’t exactly the right indicator

Still, I find this interesting:

M2 money supply growth rates are plunging in Greece (down -16.8% y/y through February), Spain (down -4.7%), and Portugal (-3.8% through January). It is up only 1.3% through February in Italy.

Germany’s M2 is up 7.5% y/y through February. Some of that growth is coming from Greece, Portugal, and Spain, where money supplies are falling as depositors move their funds to banks they deem to be safer in Germany.

The article is here. Most notable is how the various rates of money supply growth start to diverge around 2010. For the pointer I thank Alexander Schibuola.

May 14, 2012

How much structural unemployment was there during the Great Depression?

A few times recently Paul Krugman has raised the issue of structural unemployment in the Great Depression, so I thought I would offer a look at what has been written on the topic. Here is Richard J. Jensen, from a survey article:

Economists agree that Keynesian stimuli would not have helped structural or hard-core unemployment, only cyclical unemployment. As Table 1 suggests, about half of the unemployment was cyclical from 1931 through 1933; it was then that stimulus was needed and might have worked. By 1933, the appearance of a large, new, structural/hard-core element raised the natural level of unemployment from the 5 to 6 percent range to 12 to 15 percent. If a Keynesian stimulus had been tried and it had eliminated cyclical unemployment, the remaining unemployment still would have been io to 15 percent. Further fiscal or monetary stimuli would have resulted in inflation.

Later he moves directly to the key question:

…we need to discover how the war cured hard-core unemployment permanently. On the supply side, the growth of high schools and colleges, the postwar draft, and Social Security retirements removed young and old from the labor force. Wartime training and experience, in industry and in the military, made workers more productive, and upgraded skills so that the supply of unskilled labor was much smaller. In terms of efficiency wages, employers reshaped jobs to suit the skills and increase the productivity of available workers. They had to use men (and women) whom they would not have dreamed of hiring a few years before.

Personnel management became even more important. The number of industrial-relations staff rose from 2.5 per 1ooo employees in 1937 to 8.o in 1948. They were charged with improving productivity despite the extraordinary shortage of manpower, the high quit rates, the government-imposed wage freeze, and the new strength of labor unions. They dropped categorical restrictions against the poorly educated, the unemployed, women, the old, the handicapped, and sometimes, in spite of intense resistance, blacks. Recruitment of new workers became an art form, with sound trucks blaring in the streets beseeching people to come to work and earn big money. Jobs were restructured so that fewer skills were needed. Intensive in-shop and in-school training programs reached millions. Anyone with a modicum of skill was rapidly promoted, even to the status of foreman or instructor. The results further justified the use of efficiency-wage procedures, but this time efforts were made to find the right niches for workers who had been “hopelessly unemployable” in the 1930s.

In other words, the path out of high unemployment involved much more than a mere reflation of nominal values. (By the way, when it comes to terminology I might not use the phrase “structural unemployment,” but it also is not “simple cyclical unemployment.” I would say that in some circumstances the traditional distinction between cyclical and structural unemployment breaks down, but note that in terms of its parent literature this piece is using the terms properly, even if they sound somewhat off in a 2012 blogosphere context.)

In any case, history suggests that stimulus policy has to take some very specific forms to reach those “called cyclically unemployed by some, structurally unemployed by others” unemployed workers and that is the practical upshot.

Another practical upshot is that you still can believe in labor market hysteresis, as presented by DeLong and Summers. Without some analysis like the above, the DeLong/Summers claims are otherwise contradicted by American post-Depression productivity once joblessness has lifted. Where were the long-term scars? Well, they were fixed but it wasn’t easy. So hysteresis can be saved, but we still are left with proper stimulus being very difficult to do, unemployment being quite sticky, and proper policy requiring lots of structural attention. The Great Depression is evidence for all of those views, not against them.

Here is one more bit, with a sad sting at the end:

The war, by removing millions of prime men from the labor market, by restructuring the work process, by subsidizing wages, and by massive retraining, finally gave the private sector the methods and the incentives to rehire the hard-core. Never since has hardcore unemployment affected more than one worker in a hundred.

Michael A. Bernstein’s book, The Great Depression: Delayed Recovery and Economic Change in America, 1929-1939, also considers the significant role of structural unemployment (don’t forget my taxonomic caveat) in the Great Depression.

It is important to learn from this literature rather than dismiss it.

What is austerity?

Or should that read what is “austerity”?

The May 11 IHT has a headline “German line on austerity appears to soften,” and the article is about monetary policy and inflation targeting (I don’t see it on line). While monetary policy has ramifications for fiscal policy and output, I would not refer to tight money as “austerity,” in spite of the mood affiliation.

I googled “austerity define” and Wikipedia reports this:

In economics, austerity is a policy of deficit-cutting, lower spending, and a reduction in the amount of benefits and public services provided.

Notice that is mostly about spending, and notice the word “and.” I find this definition confusing, especially if one interprets the “and” strictly. Tax hikes are then mentioned:

Austerity policies are often used by governments to try to reduce their deficit spending while sometimes coupled with increases in taxes to pay back creditors to reduce debt.

That seems to make the “tax hikes” something other than “austerity policies.” The Macmillan on-line dictionary makes it all about spending and not about taxes at all.

A financial source in the top ten, Investopedia, reports this:

A state of reduced spending and increased frugality in the financial sector. Austerity measures generally refer to the measures taken by governments to reduce expenditures in an attempt to shrink their growing budget deficits.

That starts with spending, then shifts to the financial sector (?), and the second sentence shifts back to spending. That’s confusing too. How do higher taxes fit in? What are the baselines?

Krugman I do not think has offered a definition or measure of austerity (he spends more time doing a link-less attacking of others, including possibly myself, for claims about austerity which he does not document anyone making or they simply did not make), but he seems to think that automatic stabilizer-driven spending increases do not count as spending increases for the purpose of defining austerity. Neither does spending on bank bailouts count for him.

I could imagine a definition something like this: “the net effect of all government fiscal policies on ngdp, relative to the baseline of a stabilized path for expected ngdp growth.” Or should it read: “…relative to what will happen to ngdp growth in the absence of budgetary changes”? I wonder if some Keynesians have in mind the baseline of “the expansionary policies which I think would be appropriate,” in which case doing less than the Keynesian optimum is always a form of austerity. Angus notes correctly that clear definitions of austerity are hard to come by.

In Bucharest I cannot alas consult my library for further definitions.

In any case, austerity is a misleading and often misunderstood word. It is better if we describe policies more concretely, and in fact that is not hard to do. Furthermore, insisting on a clearer accounting should not be equated with “austerity denial.”

Assorted links

1. An old but still interesting Bertola and Drazen paper on fiscal policy (pdf): “We propose and solve an optimizing model which explains counterintuitive effects of fiscal policy in terms of expectations. If government spending follows an upward-trending stochastic process which the public believes may fall sharply when it reaches specific “target points,” then optimizing consumption behavior and simple budget constraint arithmetic imply a nonlinear relationship between private consumption and government spending. This theoretical relation is consistent with the experience of several countries.”

2. Should Greece default now or later?

3. Bahrain and Saudi Arabia to move toward a closer union.

4. 2005 me on the end of the euro; “It would be ironic if the strongest argument against the Euro was simply the eventual need to dissolve it.”

Greece fact of the day (but how many bullets did they fire?)

More than half of all police officers in Greece voted for pro-Nazi party Chrysi Avgi’ (Golden Dawn) in the elections of May 6. This is the disconcerting result of an analysis carried out by the authoritative newspaper To Vima (TheTribune) in several constituencies in Athens, where 5,000 police officers in service in the Greek capital also cast their ballot.

Here is more, via Chris F. Masse.

Genoeconomics

An interesting piece from the Boston Globe on “genoeconomics”:

Though the name wasn’t coined until 2007, genoeconomics flickered briefly into existence once before. In 1976, the late University of Pennsylvania economist Paul Taubman published the results of a study in which he followed the financial lives of identical twins, and found there were curious similarities in how much money they made as adults. Taubman concluded that between 18 percent and 41 percent of variation in income across individuals was heritable.

It was a startling conclusion, and one that Taubman’s fellow economists didn’t quite know what to do with. One joked that Taubman’s findings meant the government might as well shut down welfare, since clearly some people would remain poor no matter what.

….After Taubman, the idea that genes had an important role to play in decision-making was largely abandoned in the world of economics. But with the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2000, the first full sequence of a human being’s genetic code, people started wondering if perhaps it would be possible to push past broad heritability estimates, of the sort that Taubman generated, and figure out what part of a person’s genome influenced what aspect of his behavior.

…Over time, social scientists started coming to terms with the fact that even the most heritable of traits, such as height, were influenced not by one or two powerful genes, but by a combination of hundreds or even thousands—and that environmental factors, like a person’s upbringing, play a complex role in determining how those genes are expressed. “Every single direction has proved to be less promising than people originally expected,” said Laibson.

… hope lies in a new approach to data-gathering that is only just getting underway, wherein researchers look for patterns among thousands, and even millions of people—numbers that are only just becoming possible thanks to massive collaborations linking gene studies being conducted all over the world.

The researchers in question, Daniel Benjamin, David Laibson, David Cesarini and others, seem worried about the possibility of tracing attributes and behavior to genetics. Most of the big news is out already, however, and more easily observed in phenotype than genotype.

For more on the new approach see The genetic architecture of economic and political preferences.

Markets in Everything: Fashion Like

These hangers in a São Paulo store show in real-time the number of “likes” an outfit has received on the Facebook page of Brazilian fashion retailer C&A. I shudder to think how many likes my typical outfit would receive.

The internet of things is approaching rapidly.

May 13, 2012

Genoeconomics

Here is one paragraph of an interesting-but-treads-quite-lightly story about what is possibly a new field of economics:

To talk to the genoeconomists about their vision for the field is to listen to people acutely reluctant to overpromise, or to come off as naive. Much of their forthcoming paper in the Annual Review of Economics, in fact, describes how the vast majority of studies that appeared to link individual genes to specific outcomes—the amount of education people receive, whether or not they are self-employed, how they invest their money—have turned out to be impossible to replicate. Their hope lies in a new approach to data-gathering that is only just getting underway, wherein researchers look for patterns among thousands, and even millions of people—numbers that are only just becoming possible thanks to massive collaborations linking gene studies being conducted all over the world.

Jeff, the source, offers some discussion here.

Addendum: I now see in the blogging software panel that Alex has a post on the way, covering this same article, it should be up later today and maybe his take is different than mine.

Assorted links

1. Via Chris F. Masse, how large is the Chinese art market really?

2. The economics of HBO, and conditioning on a collider.

3. Good analysis of Spanish debt restructuring; “Should there be some form of Spanish sovereign bond restructuring, the amounts required to recapitalize the banks would be astronomical.”

4. Is the multi-year, multi-volume biography dead?

5. Banana battles, and how is America’s helium crisis developing?

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers