Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 341

June 28, 2013

What is the political equilibrium when insect-sized drone assassins are available?

Not bee drones, rather drone drones, with military and terrorist capabilities. There is already a (foiled) terror plot using model airplanes. How easy would it be to stop a mechanical “bee” which injects a human target with rapidly-acting poison? You can see the problem.

I have considered a few possibilities:

1. Insect-sized drones won’t make a big difference, because there are few wannabe assassins in any case. Similarly, not many people organize random attacks in shopping malls today, or try to drop poison in supermarket jars, even though such attacks are not technologically difficult.

2. Not getting caught makes all the difference, and the insect-sized drones will be hard to trace. All high-status figures who appear in public will be assassinated, so they stop appearing in public. (Where does this line get drawn? Can lieutenant governors appear in public? Or does the highest status individual who appears in public get assassinated in any case?)

3. We set up drone zappers around the rings of all major cities and high status figures stay within the confines of these safety zones. The travel industry takes a hit, as does the population of starlings. Still, some hostile drones get through the zappers and conduct some assassinations.

4. As with nuclear weapons, only the United States and other wealthy, respectable countries will have access to insect-sized drones.

5. Terror groups will be negligible in size, insider trading motives will be weak (CEOs are potential victims too), and a rationale of mutually assured insect destruction will prevail.

None of these sound especially assuring. Here is a brief survey on insect-sized drones. Here are additional readings.

As I once wrote, someday we may be longing for the era of the great stagnation.

June 27, 2013

Who is the most influential public intellectual of the last twenty-five years?

A while ago I asked a related question. But my answer blew it on one major possibility. Doesn’t Andrew Sullivan have a reasonably strong claim to that title, especially after the recent Supreme Court decisions on gay marriage? Sullivan was the dominant intellectual influence on this issue, from the late 1980s on, and that is from a time where other major civil liberties figures didn’t give gay marriage much of a second thought, one way or the other, or they wished to run away from the issue. Here is his classic 1989 New Republic essay. Here is a current map of where gay marriage is legal and very likely there is more to come.

Sullivan was also a very early blogger, and an inspiration for many in that regard (myself included), and the blogging innovation seems like it is going to stick. That’s two big wins right there, and how many other people can even come up with one?

Many of you will complain about his “war blogging,” his connection to Obama, and perhaps other matters, but no matter what you think on these issues it still seems to me he holds the lead.

Pre-Sullivan, I would give the honors to Milton Friedman.

Claims about the United Kingdom

It is not the state that the British object to, but other people.

That is from Terry Eagleton’s Across the Pond: An Englishman’s View of America, which is sometimes amusing.

Assorted links

1. 210 reasons for the fall of the Roman Empire, and the Chinese vision for the future of humanity, short film promotional video with Dwight Howard and Scottie Pippen among others; subtle, Straussian, involves genetic engineering.

2. Claims about self-control and happiness.

3. Why apes cannot pitch, and there will soon be a new Bruno Latour book, two of them in fact.

4. Markets in everything: a company with professional liars.

5. Raghuram Rajan on unconventional monetary policy after the crisis, much wisdom in this talk.

6. Recent disputes over measuring inequality.

True sentences based on lots of data

His overall conclusion is that adverse supply shocks have undesirable effects for economies even when they are at the interest rate zero lower bound.

That is from James Hamilton, citing and discussing research by Johannes Wieland.

Luck, Investment and the One Percent

Jon Chait criticizes Mankiw’s defense of the 1% for focusing on productivity as a reason why the rich earn more:

Mankiw’s essay is a sprawling mess, but it hinges on a few key premises. One is that market wealth reflects a person’s productivity. Higher taxes on the rich, he writes, would take from “the most productive members” of society and give to “society’s less productive citizens,” and he uses “productive” and rich” as synonyms throughout….

But there are lots and lots of ways that a person’s income does not measure his contribution to society. Many of us see them every day. We all know people in our field who earn too much, or too little, because of social connections, or race, or gender, or luck, or willingness to cut ethical corners of one variety or another.

But later in that same article and in a followup he argues that greater productivity is an important explanation for inequality:

Krugman noted (as did I) that more affluent parents spend far more than poor children do on “enrichment expenditures” — “books, computers, high-quality child care, summer camps, private schooling, and other things that promote the capabilities of their children.” (ital added)

Mankiw’s response is that this enrichment spending is all wasted.

…Really — high-quality child care, private schools, camps — it’s all just for fun?…There is, in fact, an enormous amount of research on this very question. And the findings overwhelmingly suggest that nonschool enrichment matters an enormous amount. A huge portion of the achievement gap between poor and nonpoor children is attributable to summer vacation.

The first claim is that the wealthy aren’t more productive than the less wealthy and the latter claim is that they are more productive but that this is unfair. The two claims are in tension (perhaps a synthesis is possible but none is offered). Note also that the two claims have quite different implications. In the former case the rich are lucky and you can tax them without generating large incentive problems. In the latter case the rich have benefited from investment and taxing the benefits is likely to reduce such investment.

Addendum: Mankiw, of course, takes the opposite end of the stick, productive people but unproductive summer camps. Mankiw, however, is not inconsistent as he offers another explanation for productivity, namely earlier developed talents and capabilities possibly even genetic in origin. I don’t want to discuss that issue in this post but here is one relevant earlier post with a bit more here for those interested .

June 26, 2013

Is the labor market return to higher education finally falling?

Peter Orszag considers that possibility in his recent column. About one in four bartenders has some kind of degree. Orszag draws heavily on this paper by Beaudry and Green and Sand, which postulates falling returns to skill. It’s one of the more interesting pieces written in the last year, but note their model relies heavily on a stock/flow distinction. They consider a world where most of the IT infrastructure already has been built, and so skilled labor has not so much more to do at the margin. This stands in noted contrast to the common belief — which I share — that “IT-souped up smart machines” still have a long way to go and are not a mature technology. You can’t hold that view and also buy into the Beaudry and Green and Sand story, unless you think we have suddenly jumped to a new margin where machines build machines, with little help from humans.

Rather than accepting “falling returns to skill,” I would sooner say that education doesn’t measure true skill as well as it used to.

The more likely scenario is that the variance of the return to having a college education has gone up, and indeed that is what you would expect from a world of rising income inequality. Many people get the degree, yet without learning the skills they need for the modern workplace. In other words, the world of work is changing faster than the world of what we teach (surprise, surprise). The lesser trained students end up driving cabs, if they can work a GPS that is. The lack of skill of those students also raises wage returns for those individuals who a) have the degree, b) are self-taught about the modern workplace, and c) show the personality skills that employers now know to look for. All of a sudden those individuals face less competition and so their wages rise. The high returns stem from blending formal education with their intangibles (there is also more pressure to get an advanced degree to show you are one of the privileged, but that is another story.)

This polarization of returns — among degree holders — explains both why incomes are rising at the top end, and why the rate of dropping out of college is rising too. At some point along the way in the college experience, lots of students realize they won’t be able to “cross the divide,” and the degree alone won’t do it for them. They foresee their future tending bar and act accordingly.

Too many discussions of the returns to education focus on the mean or median and neglect the variance and what is likely a recent increase in that variance.

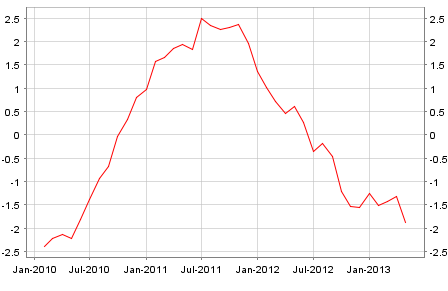

YoY growth in eurozone loans to non-financial companies

My new favorite question to ask over lunch

“So, are you a regional thinker?”

If they say no, fail them. If they say yes, ask them to explain. Here is my old favorite question to ask, and therein you find links to the very first question of this kind.

Assorted links

2. Automated coach to practice conversations (pdf).

3. .

4. Food trucks for dogs (MIE), and use Kinect to control your cockroaches.

5. The shadow banking culture that is China.

6. Miles Kimball and Matt Rognlie on wage stickiness, price stickiness, and TFP. That is also a good post showing some differences between blogospheric economics and academic economics.

7. How to give the audience too much power.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers