Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 290

October 7, 2013

The labor market effects of immigration and emigration from OECD countries

Here is a new paper by Frédéric Docquier, Çaglar Ozden & Giovanni Peri, forthcoming in Economic Journal:

In this paper, we quantify the labor market effects of migration flows in OECD countries during the 1990′s based on a new global database on the bilateral stock of migrants, by education level. We simulate various outcomes using an aggregate model of labor markets, parameterized by a range of estimates from the literature. We find that immigration had a positive effect on the wages of less educated natives and it increased or left unchanged the average native wages. Emigration, instead, had a negative effect on the wages of less educated native workers and increased inequality within countries.

A gated version of the paper is here, ungated versions are here.

Yes, I am familiar with how these models and estimates work, and yes you can argue back to a “we really can’t tell” point of view, if you are so inclined. But you cannot by any stretch of the imagination argue to some of the negative economic claims about immigration that you will find in the comments section of this blog and elsewhere.

And no I do not favor open borders even though I do favor a big increase in immigration into the United States, both high- and low-skilled. The simplest argument against open borders is the political one. Try to apply the idea to Cyprus, Taiwan, Israel, Switzerland, and Iceland and see how far you get. Big countries will manage the flow better than the small ones but suddenly the burden of proof is shifted to a new question: can we find any countries big enough (or undesirable enough) where truly open immigration might actually work?

In my view the open borders advocates are doing the pro-immigration cause a disservice. The notion of fully open borders scares people, it should scare people, and it rubs against their risk-averse tendencies the wrong way. I am glad the United States had open borders when it did, but today there is too much global mobility and the institutions and infrastructure and social welfare policies of the United States are, unlike in 1910, already too geared toward higher per capita incomes than what truly free immigration would bring. Plunking 500 million or a billion poor individuals in the United States most likely would destroy the goose laying the golden eggs. (The clever will note that this problem is smaller if all wealthy countries move to free immigration at the same time, but of course that is unlikely.)

For the initial pointer I thank Kevin Lewis.

Assorted links

2. MIE: upscale potty for $5000 a night, that is Canadian dollars perhaps.

3. “They told us giving a talk after that was a federal crime…”

4. Is Greece considering a confiscation of private assets?

5. How are they reorganizing the World Bank?

6. Michael Barone reviews Average is Over.

Trade, Development and Genetic Distance

Trade increases development but the main driver appears not to be comparative advantage and the standard microeconomic “gains from trade” but rather factors emphasized by Adam Smith and Paul Romer such as the increasing returns to scale that drives innovation and investment in R&D and also the ways in which trade increases exposure to and adoption of foreign ideas.

It’s much easier, however, to trade goods than ideas. The price of wheat shows strong convergence around the world by the 19th century but even simple ideas like hand-washing transmit much more slowly. Complex ideas like the rights of women, the rule of law or the corporate form transmit even more slowly. Thus, one of the barriers to development is barriers to the transmission of ideas.

Enrico Spolaore and Romain Wacziarg have done pioneering work uncovering some of the deep factors of development by using genetic distance as a measure of the difficulty of communicating ideas. Spolaore and Wacziarg have a short paper in Vox summarizing their methods and findings.

[G]enetic distance is like a molecular clock – it measures average separation times between populations. Therefore, genetic distance can be used as a summary statistic for divergence in all the traits that are transmitted with variation from one generation to the next over the long run, including divergence in cultural traits.

Our hypothesis is that, at a later stage, when populations enter into contact with each other, differences in those traits create barriers to exchange, communication, and imitation.

…Our barriers model implies that different development patterns across societies should depend not so much on the absolute genetic distance between them, but more on their relative genetic distance from the world’s technological frontier. For example, when studying the spread of the Industrial Revolution in Europe in the 19th century, what matters is not so much the absolute distance between the Greeks and the Italians, but rather how much closer Italians were to the English than the Greeks were. Indeed, we show that the magnitude of the effect of genetic distance relative to the technological frontier is about three times as large as that of absolute genetic distance. When including both measures in the regression, genetic distance relative to the frontier remains significant while absolute genetic distance becomes insignificantly different from zero. The effects are large in magnitude – a one-standard-deviation increase in genetic distance relative to the technological frontier (the US in the 20th century) is associated with an increase in the absolute difference in log income per capita of almost 29% of that variable’s standard deviation.

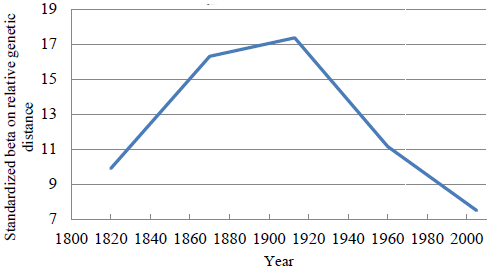

Our model implies that after a major innovation, such as the Industrial Revolution, the effect of genealogical distance should be pronounced, but that it should decline as more and more societies adopt the innovations of the technological frontier (which, in the 19th century, was the UK). These predictions are supported by the historical evidence. The figure below shows the standardised effects of genetic distance relative to the frontier for a common sample of 41 countries, for which data are available at all dates. The figure is consistent with our barriers model. As predicted, the effect of genetic distance – which is initially modest in 1820 – rises by around 75% to reach a peak in 1913, and declines thereafter.

Figure 1. Standardised effect of genetic distance over time, 1820-2005

Dupor and Li on the Missing Inflation in the New-Keynesian Stimulus

That is the title of a new and very good John Cochrane blog post on fiscal stimulus. Here is one excerpt from Cochrane:

New-Keynesian models act entirely through the real interest rate. Higher government spending means more inflation. More inflation reduces real interest rates when the nominal rate is stuck at zero, or when the Fed chooses not to respond with higher nominal rates. A higher real interest rate depresses consumption and output today relative to the future, when they are expected to return to trend. Making the economy deliberately more inefficient also raises inflation, lowers the real rate and stimulates output today. (Bill and Rong’s introduction gives a better explanation, recommended.)

So, the key proposition of new-Keynesian multipliers is that they work by increasing expected inflation. Bill and Rong look at that mechanism: did the ARRA stimulus in 2009 increase inflation or expected inflation? Their answer: No.

The paper itself is here.

October 6, 2013

Earth orbit debris: an economic model

That is a 2013 paper by Adilov, Alexander, and Cunningham, here is the abstract:

Space debris, an externality generated by expended launch vehicles and damaged satellites, reduces the expected value of space activities by increasing the probability of damaging existing satellites or other space vehicles. Unlike terrestrial pollution, debris created in the production process interacts with firms’ final products, and is, moreover, self-propagating. Collisions between debris or extant satellites creates additional debris. We construct an economic model to explore private incentives to launch satellites and to mitigate space debris. The model predicts that, relative to the social optimum, firms launch too many satellites and under-invest in debris mitigation technologies. We discuss remediation strategies and policies, and calculate a socially optimal Pigovian tax.

While we are on this topic, I very much liked the movie Gravity, which although it has some dialogue hearkens back to the silent classics of the past. It has spectacular visuals, a “great stagnation” element, a don’t try to be Icarus, live in the mud, and be reborn and baptized in the water element, a reinterpretation of The Book of Job, and a “who builds the best infrastructure anyway?” theme. On top of all that, it is subtle running commentary on the 1969 film *Marooned* and how much the world has, and hasn’t, changed since then.

Assorted links

1. Scott Sumner on British austerity.

2. Does exposure to economics make students more like economic maximizers?

3. How easily can a paper’s forthcoming citation history be predicted?

4. The shutdown-induced Straussian weather service.

5. David Bernstein’s observations on American Jewish life.

6. Great Courses with Daniel Drezner, “Foundations of Economic Prosperity.”

The back end glitches in Obamacare

Very few of the individuals trying to buy health insurance are getting through to all the steps of the federal ACA website and using it successfully. But once they register, they still may not have actual coverage plans, with successes running at what is (possibly) a one in one hundred rate:

As few as 1 in 100 applications on the federal exchange contains enough information to enroll the applicant in a plan, several insurance industry sources told CNBC on Friday. Some of the problems involve how the exchange’s software collects and verifies an applicant’s data.

“It is extraordinary that these systems weren’t ready,” said Sumit Nijhawan, CEO of Infogix, which handles data integrity issues for major insurers including WellPoint and Cigna, as well as multiple Blue Cross Blue Shield affiliates.

Experts said that if Healthcare.gov‘s success rate doesn’t improve within the next month or so, federal officials could face a situation in January in which relatively large numbers of people believe they have coverage starting that month, but whose enrollment applications are have not been processed.

There is more here, via Megan McArdle, who for years has been predicting major problems with the web sites. By the way, these are not fundamentally problems of high usage or high demand.

Average is Over

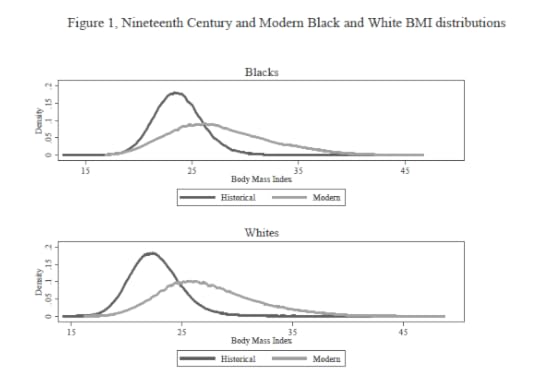

There has been an increase in the mean body-mass index since the 19th century but even more strikingly there has been an increase in the variance, what we might call an increase in weight inequality. More here.

Hat tip: Andrew Leigh.

October 5, 2013

Using eminent domain to halt foreclosure

Richmond, California has developed a new trick, achieving an effect similar to principal reduction:

Richmond condemns mortgages on homes that are now worth far less than what the borrower owes. The note holders — investors such as pension funds and mutual funds – are forced to settle for the current fair market value. The city pays for this with cash from a new set of investors, who now own the mortgage. The new price is set by the current market, and the homeowner settles into a more manageable loan.

From Lydia DePillis at Wonkbook, the full story is here. This part is interesting too:

Richmond couldn’t get insurance to shield it from a crushing judgment — if it lost its bid to spare struggling homeowners, the city could find itself underwater.

In the backlash to the plan, the market boycotted the city’s most recent bond issuance, forcing it to withdraw the $34 million offer, which was supposed to refinance earlier debt.

Richmond’s leaders stared hard at the threats. In the end, it seemed to only harden their resolve.

The seizures have not yet happened, but are pending, and it is expected that Richmond will need to defend itself in court.

Assorted links

1. How did popcorn come to be associated with the movies?

2. The ascendancy of data in eight young economics stars.

3. “Hauling iron ore across Australia’s outback pays some 400 engineers about $224,000 per year, but the gravy train is coming to an end thanks to robots.” The Ricardo effect.

4. Possibly innocent man was held in solitary confinement for 41 years, he has now passed away.

5. Does eye contact harm your case? (speculative)

6. Watson, meet your new partner, Amos.

7. www.grundeinkommen.ch. Wikipedia ist hier.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 843 followers