Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 263

November 29, 2013

Debt should be compared to wealth, not just to gdp

Here is a good point about Japan:

If there’s one asterisk to put after the shocking comparative figures, it’s that the debt-to-GDP ratios don’t take into account Japan’s huge asset holdings. At the end of March 2012, Japan’s central government had assets totaling some Y600 trillion, roughly half of its total liabilities projected for next March, separate MOF data show. And those assets include Y250 trillion in cash, securities and loans. Critics often say Japan’s fiscal health could quickly improve if the government sells some of those assets, a step the MOF is reluctant to take partly on worries that doing so could deprive lawmakers of incentives to improve government finances.

Here is my July NYT column on related matters.

Assorted links

1. Using electronic medical records to correlate genes with illnesses.

2. It’s not always easy to retract a paper.

3. What is the best year for movies ever?

4. My 2011 post on the economics of Black Friday.

5. Are locality-backed minimum wage hikes the new trend? Keep in mind that unless you have the Sea-Tac airport or some comparably immobile resource in your district, it is harder to make them work if the wage change is local only. This is a classic instance of expressive voting at the expense of good economic policy.

November 28, 2013

Net immigration into the UK, recent trends

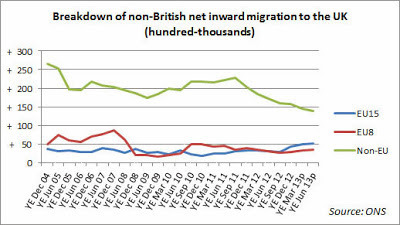

This picture clarifies a few neglected points:

Since 2010 there has been a marked decline in non-EU net immigration. As a proportion of non-British immigration to the UK, it has dropped from 73% in June 2010 to 57% in June 2013. In the last year alone, it has fallen from 172,000 to 140,000.

Meanwhile, this year, net migration from the EU has gone up by 72,000 to 106,000.

But, as the chart above shows, the recent increase in net EU migration has come from the older, more established (and traditionally more wealthy) EU member states (the EU15), not the new member states from central and eastern Europe that joined in 2004 (the EU8).

That is from Open Europe Blog.

Which characteristics of economics departments predict productivity of publications?

In some recent work, Bosquet and Combes look at French data (only) and correlate the quality of economics departments with some of their underlying features. Why did they chose France?: “The most frequent way of becoming a full professor is via a national contest that allocates winners to departments in a largely random way.”

So what do we learn? First, large departments are in per capita terms not so much more productive and not at all doing better in terms of quality. Proximity to other economics departments also does not matter.

And then:

Heterogeneity among researchers in terms of publication performance has a large, negative explanatory power.

I suspect some of this is causal. It is good for departments to get rid of their dead wood and good when departments insist that everyone produce.

There is also this:

The second department characteristic that has the highest explanatory power of individual publication performance is the diversity of the department in terms of research fields (within economics).

I wonder there how much the allocation of researchers is truly random. I find the reverse causality story more plausible, namely that the strongest departments have the resources and heft to cover a larger number of fields, as it is less likely that having people scattered across many fields makes the department as a whole more productive.

In your spare time, you might also ponder this:

Finally, other department characteristics have interesting properties.

Contrary to common intuition, more students per academic do not reduce publication performance.

Women, older academics, stars in the department and co-authors in foreign institutions all have a positive externality impact on each academic’s individual outcome.

For the pointer I thank Mills Kelly.

Assorted links

1. Three key facts about Japan’s deteriorating demographics.

3. Spectator picks for book of the year. And from The Observer.

4. Is the economics job market picking up?

5. Drone tries to sneak contraband into Georgia prison.

What I’ve been reading

1. The Great Mirror of Folly: Finance, Culture, and the Crash of 1720, edited by William N. Goetzmann, Catherine Labio, K. Geert Rouwenhorst, and Timothy G. Young, with a foreword by Robert J. Shiller. A beautiful full-size book with amazing plates as well as text. Think of this as a book about a book, focusing on a Dutch publication around the time of the bubble called The Great Mirror of Folly, “a unique and splendid record of the financial crisis and its cultural dimensions.” Recommended to anyone with an interest in the economic history of bubbles.

2. Catherine Hall, Macaulay and Son: Architects of Imperial Britain. An engaging and well written book about Thomas Macaulay’s father Zachary and then Thomas himself, focusing on themes of slavery, cosmopolitanism, liberalism, and empire, not to mention the education of children. A good read on why some strands of liberalism hit such a dead end when confronted with the realities of the British empire.

3. Iain MacDaniel, Adam Ferguson in the Scottish Enlightenment: The Roman Past and Europe’s Future. A clear and conceptually argued account of Ferguson’s thought, which will convince you he is not the lightweight of the Scottish Enlightenment. Starting with a comparison with Montesquieu, MacDaniel emphasizes Ferguson as a critic of the idea of progress and a historical pessimist, focusing on issues of war and martial virtue. This book is also useful for understanding the subtleties of Smith on the ancients vs. the moderns and why he was more sanguine about Britain than about the Romans (no slavery, for one thing).

4. John Eliot Gardiner, Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven. One of the world’s greatest Bach conductors is also one of the greatest Bach writers, with an emphasis on the vocal music and also what we know about Bach’s life. Especially noteworthy is the lengthy case for the John Passion and the discussion of the B Minor Mass. Definitely worthy of the “best books of the year” list and perhaps in the top tier too. I’m not going to liberate this volume, I am going to keep it.

November 27, 2013

The economic gains from a better allocation of talent

Michael Clemens directs our attention to a February 2013 paper by Chang-Tai Hsieh, Erik Hurst, Charles I. Jones, and Peter J. Klenow, here is the abstract:

In 1960, 94 percent of doctors and lawyers were white men. By 2008, the fraction was just 62 percent. Similar changes in other highly-skilled occupations have occurred throughout the U.S. economy during the last fifty years. Given that innate talent for these professions is unlikely to differ across groups, the occupational distribution in 1960 suggests that a substantial pool of innately talented black men, black women, and white women were not pursuing their comparative advantage. This paper measures the macroeconomic consequences of the remarkable convergence in the occupational distribution between 1960 and 2008 through the prism of a Roy model. We find that 15 to 20 percent of growth in aggregate output per worker over this period may be explained by the improved allocation of talent.

The pdf is here. Addendum: I am informed Alex mention this piece in an earlier post.

The Betrayers Banquet

Here is something for you to try out tomorrow with the family, well some families. The Betrayers’ Banquet is a dinner party/event that ingeniously combines the iterated prisoner’s dilemma with good food, bad food and entertainment. Here is their description:

The event works as follows:

A banqueting table is set with 48 chairs, 24 on each side, at which players are seated at random. For a period of two hours, the food is served in small portions every fifteen minutes, and varies in quality; at the top end of the table, it is exquisite – food you could expect at a fancy restaurant. At the bottom end, the food is charitably described as unpalatable. In between, it is a spectrum between these two extremes.

At regular intervals, pairs of opposing diners are invited to play a round of the prisoner’s dilemma with each other; They are each provided with a small wooden coin with symbols on each side representing cooperation and betrayal, which they place on the table concealed under their palms, and then simultaneously reveal:

If they both cooperate, then they are both moved up five seats towards the good food.

If they both betray, they are both moved five seats down towards the worse food.

If one betrays and one cooperates, the betrayer moves up ten seats, and other down ten seats.

The event is presented as an initiation ritual of a freemason–esque secret society; service is run by servers in hooded robes and the game is arbitrated by a dour, unsympathetic master of ceremony, who punctuate the courses with grave speeches describing the discovery of the game in the court of Charlemagne in the eighth century.

From the participant’s point of view, aside from getting to play a game and try a variety of different foods, the main attraction is that they get to move around the table and talk to a variety of people throughout dinner. The iterated prisoner’s dilemma is famous for creating very complex social dynamics, which keeps conversation lively and generates a high eagerness to continue playing.

Assorted links

1. Can you now taste the internet? And some odd photos from the year (you have to sit through a short ad).

2. Kenneth Arrow on malaria economics.

4. Did the swine flu pandemic of 2009 kill eleven times more people than we had thought?

But is he on time for low status people?

Being 50 minutes late for his first meeting with Pope Francis was nothing unusual for Russian President Vladimir Putin. That’s just the way he is — a character trait that provides some insight into his attitude toward power.

When Putin arrived on time to an audience with Pope John Paul II in 2003, the punctuality was considered a newsworthy aberration: “The President Was Not Even a Second Late,” read the headline in the newspaper Izvestia. He had been 15 minutes late for a similar audience in 2000.

The waits other leaders have had to endure in order to see Putin range from 14 minutes for the Queen of England to three hours for Yulia Tymoshenko, the former Ukrainian prime minister. Few people are as important in terms of protocol as the queen or the pope, and there is no country Putin likes to humiliate as much as Ukraine.

The typical delay seems to be about 30 minutes. Half an hour is enough in some cultures to make people mad. Koreans saw Putin’s 30-minute lateness for a meeting with their President Park Geun Hye as a sign of disrespect.

Everybody endures the wait, though.

There is more here, hat tip to Elizabeth Dickinson.

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers