Tyler Cowen's Blog, page 171

June 2, 2014

Piketty v. Solow

Krusell and Smith lay out the Solow and Piketty growth models very nicely but perhaps not in a way that is immediately transparent if you are not already familiar with growth models. Thus, in this note I want to lay out the differences using the Super Simple Solow model that Tyler and I developed in our textbook. The Super Simple Solow model has no labor growth and no technological growth. Investment, I, is equal to a constant fraction of output, Y, written I=sY.

Capital depreciates–machines break, tools rust, roads develop potholes. We write D(epreciation)=dK where d is the rate of depreciation and K is the capital stock.

Now the model is very simple. If I>D then capital accumulates and the economy grows. If I

Steady state is thus when sY=dK so we can solve for the steady state ratio of capital to output as K/Y=s/d. I told you it was simple.

Now let’s go to Piketty’s model which defines output and savings in a non-standard way (net of depreciation) but when written in the standard way Piketty’s saving assumption is that I=dK + s(Y-dK). What this means is that people look around and they see a bunch of potholes and before consuming or doing anything else they fill the potholes, that’s dK. (If you have driven around the United States recently you may already be questioning Piketty’s assumption.) After the potholes have been filled people save in addition a constant proportion of the remaining output, s(Y-dk), where s is now the Piketty savings rate.

Steady state is found exactly as before, when I=D, i.e. dK+s(Y-dK)=dK or sY=sdK which gives us the steady level of capital to output of K/Y=s/(s d).

Now we have two similar looking expressions for K/Y, namely s/d for Solow and s/(s d) for Piketty. We can’t yet test which is correct because nothing requires that the two savings rates be the same. To get further suppose that we now allow Y to grow at rate g holding K constant, that is over time because of better technology we get more Y per unit of K. Since Y will be larger the intuition is that the equilibrium K/Y ratio will be lower, holding all else the same. And indeed when you run through the math (hand waving here) you get expressions for the Solow and Piketty K/Y ratios of s/(g+d) and s/(g+sd) respectively, i.e. a simple addition of g to the denominator in both cases (again bear in mind that the two s’s are different.)

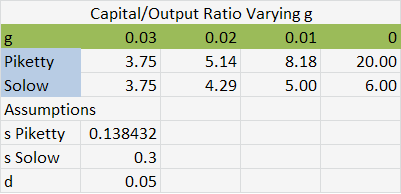

We can now see what the models predict when g changes–this is a key question because Piketty argues that a fall in g (which he predicts) will greatly increase K/Y. Here is a table showing how K/Y changes with g in the two models. I assume for both models that d=.05, for Solow I have assumed s=.3 and for Piketty I have calibrated so that the two models produce the same K/Y ratio of 3.75 when g=.03 this gives us a Piketty s=.138.

As g falls Piketty predicts a much bigger increase in the K/Y ratio than does Solow. In Piketty’s model as g falls from .03 to .01 the capital to output ratio more than doubles! In the Solow model, in contrast, the capital to output ratio increases by only a third. Remember that in Piketty it’s the higher capital stock plus a more or less constant r that generates the massive increase in income inequality from capital that he is predicting. Thus, the savings assumption is critical.

I’ve already suggested one reason why Piketty’s saving assumption seems too strong–Piketty’s assumption amounts to a very strong belief that we will always replace depreciating capital first. Another way to see this is to ask where does the extra capital come from in the Piketty model compared to Solow? Well the flip side is that Solow predicts more consumption than Piketty does. In fact, as g falls in the Piketty model so does the consumption to output ratio. In short, to get Piketty’s behavior in the Solow model we would need the Solow savings rate to increase as growth falls.

Krusell and Smith take this analysis a few steps further by showing that Piketty’s assumptions about s are not consistent with standard maximizing behavior (i.e. in a model in which s is allowed to vary to maximize utility) nor do they appear consistent with US data over the last 50 years. Neither test is definitive but both indicate that to accept the Piketty model you have to abandon Solow and place some pretty big bets on a non-standard assumption about savings behavior.

June 1, 2014

When do we want regulation in addition to a Pigouvian tax?

I haven’t followed the details of President Obama’s campaign to regulate fossil fuels through the EPA, but I thought it was worth reviewing when regulations might be desirable in addition to Pigouvian taxes.

One problem with a Pigouvian tax is you may fail to meet the threshold of a desired outcome, given that the market response to the tax is uncertain. For instance if the government put on a stiff carbon tax there is a chance dirty coal use simply might continue, albeit at higher prices, and thus no problem would be solved. A very very high tax could ensure a movement away from dirty coal but then perhaps the tax is much higher than it needs to be and that too will bring significant distortions.

In that case, it can in principle make sense to supplement the Pigouvian tax with some kind of “best practices” standard or quantity regulation on the side of emissions.

Now here’s the catch. Let’s say you have been arguing that the transition to green energy can be a smooth and certain glide. In that case you should want the tax only (admittedly you still might favor direct regulation as a substitute, given the absence of a tax).

Let’s say you wring your hands about the ability of the market to find a good substitute for the dirtier fossil fuels. You’re really not sure whether that can be done or not at a reasonable price.

In that case there is the uncertainty and you might favor the Pigouvian tax plus the regulation. Or if you are truly fearful about substitutability, and don’t assign high enough priority to emissions control and climate issues, you might want no tax and also no major regulations.

One odd mix of positions is “I’m very unsure how well and how smoothly this transition will go and I want only a Pigouvian tax.”

Another odd mix is “I’m sure this transition will be a smooth and easy glide, I want both Pigouvian taxes and lots of regulation.”

The new Godzilla movie, *Godzilla* (minor spoilers in post)

I know I am late on this one, but I thought it was pretty damned good, well above expectations. I feel comfortable placing it in the top five Godzilla movies of all time. The visuals are spectacular but not overdone, and it pays appropriate homage to its sources, including the Japanese original but also Hitchcock’s The Birds. The movie also treats nuclear weapons use with the moral seriousness it deserves, which is rare these days.

And is there a Straussian reading? Well, yes (did you have to ask?). The film is really a plea for an extended and revitalized Japanese-American alliance. The real threat to the world are the Mutos, not Godzilla, who ends up defending America, after the lead Japanese character in the movie promises the American military Godzilla will be there as our friend (don’t kill me, that is not a major spoiler as it is telegraphed way in advance).

The Mutos, by the way, are basically Chinese mythological dragons, and an image of two kissing Muto-like beings is shown over the gate of San Francisco’s Chinatown three different times in the movie, each time with greater conspicuousness. Note that the Mutos can beat up on Godzilla because of their greater numbers, but as for one-on-one there is no doubt Godzilla is more fierce. And the name of the being — Muto — what does that mean? I believe loyal MR readers already know, and apologies for reminding you. General Akira Muto led the worst excesses committed by Japanese troops during the Rape of Nanjing, perhaps the single biggest Chinese grievance against The Land of the Rising Sun, and thus the beings are a sign of the Chinese desire for redress and revenge. Unless of course the right military alliance comes along to contain them and save the world…

The references to Pearl Harbor and the Philippines are not accidents either.

*Becoming Freud*

That is the new and excellent book by Adam Phillips, in the US available on Kindle only. Here is one bit:

…Freud was discovering that we obscure ourselves from ourselves in our life stories; that that is their function. So we will often find that the most dogmatic thing about Freud as a writer is his skepticism. He is always pointing out his ignorance, without ever needing to boast about it. He is always showing us what our knowing keeps coming up against; what our desire to know might be a desire for.

And later:

Psychoanalysis would one day be Freud’s proof that biography is the worst kind of fiction, that biography is what we suffer from; that we need to cure ourselves of the wish for biography, and our belief in it. We should not be substituting the truths of our desire with trumped-up life stories, stories that we publicize.

Recommended.

Assorted links

1. Good Naidu essay on Piketty. And a good Guardian piece on data discontinuities in Piketty. More from Krusell and Smith, Piketty vs. modern macro theory. Kevin Vallier on Piketty’s political philosophy. Don Boudreaux reviews Piketty. David Graeber does a mood affiliation take on Piketty. And yet more mood affiliation on Piketty.

2. The economics of book festivals, an FT piece.

3. Tax policy and The Bible, by Bruce Bartlett.

4. E. Glen Weyl has a new paper summarizing price theory.

5. Not since 1952 have the puffins been so late. And Art Carden is returning to EconLog.

6. A tale of two brothers, one of whom is rich.

Financial Hazards of the Fugitive Life (*On the Run*)

That is the title of my New York Times Economic View column, also now on The Upshot. The column covers Alice Goffman’s excellent book On the Run: Fugitive Life in an American City. Here is one excerpt from the column:

You may think of being on the run as a quandary for only a small group of recalcitrant, hardened criminals. But in her study of one Philadelphia neighborhood, Professor Goffman shows that it is a common way of life for many nonviolent Americans. These people often face charges related to possession or sale of small amounts of drugs, or offenses like hiding relatives from the law. Whatever the negative moral implications of such crimes, they don’t merit having one’s life ruined.

A core point of “On the Run” is that “young men’s compromised legal status transforms the basic institutions of work, friendship and family into a net of entrapment.” For instance, the police round up fugitives by monitoring and contacting their relatives — and that frays family relations. A young man might avoid showing up at the hospital to witness the birth of his child because he knows he could be caught or turned in. Family gatherings become another hazard, so in-person appearances are often surprise visits. People stuck in this kind of limbo are also reluctant to visit hospitals when they need treatment, and a result, the book says, is a “lifestyle of secrecy and evasion,” driven by the unfavorable incentives set in motion by the law.

For all the recent talk of a surveillance state created through the National Security Agency, an oppressive low-tech surveillance state has been in place for decades — and it’s been directed at many of America’s poorest people.

There is also this:

As every friend or relative becomes a potential informant, cooperation plummets and life degenerates into a day-to-day struggle to remain outside the reaches of the law. Professor Goffman offers a chilling portrait of tactics used to encourage relatives to turn in possible lawbreakers: For example, the police may tell mothers that if they don’t report their errant men, the authorities will yank their children, a threat that may be backed by a charge of harboring or aiding and abetting a fugitive. “Squealing” thus becomes more likely. A community becomes divided between those who are on the clean side of the law and those who are not. And trust breaks down in personal relationships.

In large part I blame the war on drugs for these developments, as I explain in the column.

Goffman’s book is superbly researched and extremely well-written and it may well be the best social science book of the year so far. You can buy it here. And I didn’t even cover the very best part of On the Run in my column, namely the author’s account of her own personal experiences doing the research, read it carefully.

May 31, 2014

How is income inequality correlated with wealth inequality?

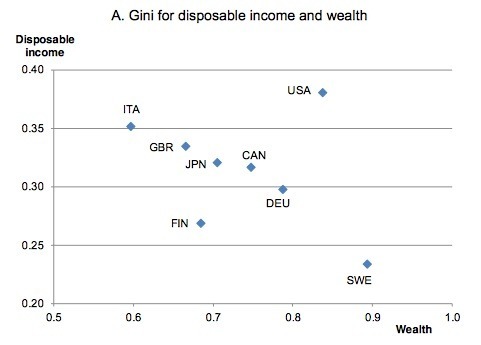

From the OECD, Kaja Bonesmo Frederiksen writes on “More income inequality and less growth” and presents this table:

If you were to fit that with a curve, the overall slope would be negative, suggesting a negative empirical correlation between income inequality and wealth inequality. Now do not leap to a conclusion here, as there are points to be made:

1. This scatter plot is not based on a model with adjustments for confounding factors.

2. These may not be the right or best data on wealth inequality.

3. There are not many data points on this graph in the first place.

4. Lots of other stuff.

The point is that everyone is talking about wealth inequality lately, yet it is not always recognized that the relationship between wealth and income inequality is complex, as illustrated for instance by the case of Sweden. (There is nothing in this post by the way which should be construed as criticism of Piketty, I’m just trying to lay out some basic expository principles.)

Wealth inequality and income inequality may diverge for at least three reasons. First, savings rates may differ across societies. Second, locally available rates of return may differ. Third, the ups and downs of mobility may mean high income inequality in a given year but overall lower levels of wealth inequality.

By the way, here is a good sentence from the abstract:

Wealth dispersion [inequality] is especially high in the United States and Sweden

The support document is , I have reproduced Figure 3a. Hat tip goes to Luis Pedro Coelho.

Pi.rate

The latest example of Intellectual Privilege running out of control is a guy who trademarked the symbol Pi with a period afterwards. Here is Jez Kemp:

Designers are in uproar and filing counter notices after print company Zazzle upheld a man’s claim to own the pi symbol on clothing.

Paul Ingrisano, a pirate living in Brooklyn New York, filed a trademark under “Pi Productions” for a logo which consists of this freely available version of the pi symbol π from the Wikimedia website combined with a period (full stop). The conditions of the trademark specifically state that the trademark includes a period.

The trademark was granted in January 2014 and Ingrisano has recently made trademark infringement claims against a massive range of pi-related designs on print-on-demand websites including Zazzle and Cafepress.

Surprisingly, Zazzle accepted his claim and removed thousands of clothing products using this design, emailing designers that their work was infringing Pi Productions’ intellectual property – even designs not using a full stop.

At first Zazzle’s Content Review team responded to their very angry designers and store keepers with generic emails, suggesting they file counter notices if they felt aggrieved.

But now Zazzle’s latest response is that they are acting to protect Paul Ingrisano’s “intellectual property” from “confusingly similar” designs as under the Lanham Act 1946 - including designs which do not even contain the pi symbol, but just the word “pi” in their design name.

I don’t expect this particular outrage to last but as with absurd patents the real outrage is that this does accurately represent the law as it exists today.

Should Scotland leave the UK?

I very much agree with the recent FT columns by Martin Wolf and Simon Schama. The Union of 1707 was one of the great events of the eighteenth century for Britain, and it paved the way for the Industrial Revolution, Adam Smith, David Hume, John Stuart Mill, and much much more, including the later United States and many of the Founding Fathers. And yes some of the excesses of imperialism, exploration too. That union truly was a cornerstone of the modern world, of the sort they might put into a book subtitle in a corny way and yet it would be quite justified.

Maybe you think the partnership hasn’t been as fruitful in recent years. Still, I view it this way. For all its flaws, the UK remains one of the very best and most successful countries the world has seen, ever. And there is no significant language issue across the regions, even though I cannot myself understand half of the people in Scotland. Nor do the Scots have a coherent or defensible answer as to which currency they will be using, or how they would avoid domination by Brussels and Berlin. If a significant segment of the British partnership wishes to leave, and for no really good practical reason, it is a sign that something is deeply wrong with contemporary politics and with our standards for loyalties.

I find this entire prospect depressing, and although it is starting to pick up more coverage in the United States and globally, still it is an under-covered story relative to its importance.

This is a referendum on the modern nation-state, an institution that has done very well since the late 1940s but which is indeed often ethnically heterogeneous at its core. While I expect Scottish independence to be voted down, if it passes I will feel the world’s risk premium has gone up, even if the Scots manage to make independence work.

Addendum: Is this the sort of debate that the great British Parlamentarians of history would have approved of?:

Alex Salmond, Scotland’s first minister who is leading the campaign for independence, said on Wednesday that each household would receive an annual “independence bonus” of £2,000 – or each individual £1,000 – within the next 15 years if the country votes to leave the UK.

The UK government, in contrast, claimed that if Scots rejected independence each person would receive a “UK dividend of £1,400 . . . for the next 20 years”.

Was that the sort of discourse you wanted? Was “being British” simply not good enough for you?

May 30, 2014

Economics and Religion, at Econ Journal Watch

The new issue of Econ Journal Watch is online at http://econjwatch.org

In this issue:

A symposium co-sponsored by the Acton Institute:

Does Economics Need an Infusion of Religious or Quasi-Religious Formulations?

The Prologue to the symposium suggests that mainstream economics has unduly flattened economic issues down to certain modes of thought (such as ‘Max U’); it suggests that economics needs enrichment by formulations that have religious or quasi-religious overtones.

Robin Klay helps to set the stage with her exploration “Where Do Economists of Faith Hang Out? Their Journals and Associations, plus Luminaries Among Them.”

Seventeen response essays are contributed by authors, representing a broad range of religious traditions and ideological outlooks:

Pavel Chalupníček:

From an Individual to a Person: What Economics Can Learn from Theology About Human Beings

Victor V. Claar:

Joyful Economics

Charles M. A. Clark:

Where There Is No Vision, Economists Will Perish

Ross B. Emmett:

Economics Is Not All of Life

Daniel K. Finn:

Philosophy, Not Theology, Is the Key for Economics: A Catholic Perspective

David George:

Moving from the Empirically Testable to the Merely Plausible: How Religion and Moral Philosophy Can Broaden Economics

Jayati Ghosh:

Notes of an Atheist on Economics and Religion

M. Kabir Hassan and William J. Hippler, III:

Entrepreneurship and Islam: An Overview

Mary Hirschfeld:

On the Relationship Between Finite and Infinite Goods, Or: How to Avoid Flattening

Abbas Mirakhor:

The Starry Heavens Above and the Moral Law Within: On the Flatness of Economics

Andrew P. Morriss:

On the Usefulness of a Flat Economics to the World of Faith

Edd Noell:

What Has Jerusalem to Do with Chicago (or Cambridge)? Why Economics Needs an Infusion of Religious Formulations

Eric B. Rasmusen:

Maximization Is Fine—But Based on What Assumptions?

Rupert Read and Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

Religion, Heuristics, and Intergenerational Risk Management

Russell Roberts:

Sympathy for Homo Religiosus

A. M. C. Waterman:

Can ‘Religion’ Enrich ‘Economics’?

Andrew M. Yuengert:

Sin, and the Economics of ‘Sin’

Tyler Cowen's Blog

- Tyler Cowen's profile

- 844 followers