Kristy Athens's Blog, page 9

July 14, 2013

Bachelorette Living in FoodieLand, USA

I am taking an online class called “Sustainability of Food Systems: A Global Life Cycle Perspective” via the website Coursera. I’m considering it practice, as I will start a low-residency graduate program called “Food Systems and Society” at Marylhurst University this fall. I figure it’s practice for both the subject matter and the forum; the last time I was in college, I transcribed my papers to an electric typewriter after composing them longhand. This 21st-century virtual classroom is a new thing for me.

Anyway … in learning about food loss (the spoilage and damage involved in growing, processing and transporting food) and food waste (the food that is never eaten because the person who has it throws it out) one of our exercises was to describe a meal we ate in great detail, paying special attention to where things come from and where they go. The online discussion is super-interesting—the students live all over the world, and their answers demonstrated similarities and differences in food and preparation. For example, a woman in Singapore ate for breakfast broth and spring rolls with rice noodles and scallions. This sounds delicious, but I would be hungry again in about eight minutes. Must. Have. Protein.

I thought I would share my response, since it is part comedy—it validates my reputation as a Domestic Not-Goddess—and part study in food systems:

Because my spouse, who is the family cook, is out of town, I was left to my own devices in the kitchen for dinner this evening, which usually results in my grazing straight from the refrigerator. Today was no exception. I ate, in “courses” rather than all at once:

Two pieces of chicken that were grilled last week. I ate them cold.

Five carrot sticks (the “baby” carrot variety; not true immature carrots but larger ones that have been shaved to child-size). Aside: Does anyone else experience the inability to swallow carrots after a while? Five mini-carrots was pretty good for me; usually, it’s more like three. My throat just closes up and I have to wash the last bite down with water.

Havarti cheese, cut from a small block, in pieces.

Two pork breakfast sausages, heated in microwave, with maple syrup.

Not much of a meal, I know. I am not a good cook, and subsequently I dislike doing it. One good thing about grazing: using up all the random items that might otherwise go to waste! (Like the grilled asparagus I found in a plastic storage container; it was unfortunately too far gone to eat, so it went into the compost.)

My meal involved no other ingredients, except on the chicken, which was prepared last week by my spouse, and so it had some kind of marinade: let’s say olive oil, balsamic vinegar and oregano. Most of this food came New Seasons, which we affectionately call “The Convenience Store” because it is about five blocks from our house (walking distance) and because, like a traditional convenience store, has inflated (or, at least, high) prices. I will now discuss eat food item in particular, and try to address all the questions.

Chicken

The chicken was originally purchased whole, and I’m pleased to report that it came from a farm just outside of Portland. I bought the olive oil at the Mother Earth News Fair that was in Puyallup, Washington, in June; the bottler is from Kansas and they work with an organic grower in Greece. The balsamic is inexpensive dreck from Trader Joe’s, full of caramel coloring. The oregano came from my side yard.

Because the chicken came from a reputable farm that engages in free-range and organic practices, I feel confident that this chicken ate a combination of organic feed and whatever insects and grasses it could find while ranging. I talked to the purveyor of the olive oil and they are on the up-and-up as far as being a family-owned business and supporting sustainable growers in Greece. But there’s still the issue of transporting olives to Kansas and then to Washington, where I drove 150 miles from Portland to buy it (though I would have been there regardless).

Carrots

The carrot sticks were an impulse buy at Fred Meyer when I was preparing for a picnic a couple of weeks ago. Probably grown in California. They required a lot of water and probably fertilizer, and then this silly shaving-into-“baby”-carrots processing.

Havarti

The cheese is imported from Holland; I would normally not buy such a thing when plenty of great cheese is made in Oregon, or Wisconsin at the furthest, but I was buying lots of small rounds-ends just for fun and variety. My favorite so far was an Oregon-made Perrydale!

Breakfast Sausages

The pork was raised and processed about 150 miles from Portland. The pig ate any number of things. This is, again, a humane free-range operation so it hopefully got some yummy food scraps now and again, and probably mostly grain. It was born sometime last year and slaughtered sometime this year.

I bought the jug of Wisconsin maple syrup myself when I was there last year visiting. It, and their cheddar, are the best. Vermont be damned.

The sausages were cooked this weekend using a gas range; I re-heated two links for 30 seconds in our microwave oven.

Other Questions

Most of my food was transported by truck, and then either my car or walked home. The olives probably came on a ship and then train or truck to Kansas. The syrup flew to Portland in my checked baggage, where, according to the nice note the TSA left me, it was found not to be a bomb.

All of it came in some kind of plastic. I am not sure what can be done about that. We will put the syrup bottle in the recycling once it’s empty, but the rest of the packaging went into the trash. Once the original packaging is removed but there is still food left over, we put it in reusable, plastic containers for storage in the refrigerator. The City of Portland has a municipal composting program; if it didn’t I would compost in our back yard.

I mostly used my fingers for this meal! I ate the chicken cold, ate the carrots straight out of their bag, cut the cheese with a paring knife and ate it, and used a fork to eat the sausages, which I did put on a small plate. Note: I do not eat this way when my husband is home!

The only water I used was to drink. Portland’s water comes from a watershed called Bull Run; it’s located about 50 miles east of the city in the Cascade Mountain range. It is very good water, so good people won’t abide the idea of putting fluoride in it, even though Portland is one of the last municipalities to refuse.

The kitchen is about 10 feet by 12 feet. Our natural gas (heat and stove) probably comes from Wyoming? I’m not sure, and the electricity mostly is generated by the Bonneville Dam, which is in the nearby Columbia River. We do buy the sustainable-energy credits, so a tiny portion comes from wind turbines in the Columbia River Gorge.

When I wash my dishes I will use hot water (gas heater) and a sponge and liquid dish soap that is sustainable in some way or another (no phosphates? Recycled plastic bottle?).

So—Think of your next meal this way! What resources were depleted to make it? How much of it was wasted? What does it mean when people talk about a global food shortage, and yet so much food is wasted?

I’m sure this an overly used phrase in the industry, but it’s Food for Thought.

July 7, 2013

Guest Post: “Parade” Essay

Julie Jindal’s name might sound familiar if you’ve been reading this blog a while—she wrote a guest post last November and is referenced in other posts here and there. She was recently published in Oregon Humanities magazine; it’s a short piece that describes her coming to embrace her small town’s Independence Day celebration. Click here to read the original published piece.

June 30, 2013

Playing Fair … Or, Not

On Tuesday evening, at 7:45, I was casually scanning my Facebook feed, where a friend in New York said that something interesting was going on in the Texas Senate.

I knew that a woman had been filibustering that day to defend Texas women’s right to safe abortion procedures, but I hadn’t paid much attention to it, considering it a noble but lost cause. I mean, this was Texas we were talking about. Rick Perry’s Texas. I posted a link to an article about the filibuster—my small contribution to acknowledge Senator Davis’s effort.

Regardless of one’s personal convictions about abortion, the evening that unfolded was an incredible display of the political process in this country. Legislators learn the system and then figure out ways to “work” it, and sometimes lose sight of their mission as public servants, which is to actualize the will of the people and defend the Constitution of the United States. Sometimes, their focus shifts to personal gain and/or personal beliefs. On Tuesday, it was the Republican party demonstrating this, but it could also just as well have been Democrats. As John Dalberg-Acton noted 150 years ago: Absolute power corrupts absolutely.

I clicked on my friend’s link, which brought me to a live feed on YouTube that had about 35,000 viewers. It was standard CNN-style documentation: a camera at the back corner of the room, taking a long shot of the senate chamber. Boring. People in suits were milling around or conferring in small groups. No one was saying anything; in fact, there was no sound at all.

I noted this on Facebook. “They’re discussing a point of order,” my friend posted.

Not interesting, I thought, and moved to my email. I left the window open, though, just in case they came back.

A few minutes later, they did. What I’d missed was Sen. Davis’s filibuster having been challenged for the third time. A few of her colleagues were suggesting that her discussion of sonograms—a mandatory step in the abortion process in Texas—was not “germane” to her discussion of the bill in question.

Over the course of the next two hours (the legislative session ended at midnight, and I live in the Pacific time zone), I sat, spellbound, as some senators tried to defend the filibuster by calling for parliamentary procedure inquiries, and the senate president begrudgingly allowed them, unless he felt he could get away with not allowing them, which he also did a bunch of times. As my Facebook friends and I exchanged impassioned color commentary, the ticker of how many people were tuned in kept climbing. By 8:30, it had doubled to 70,000. Then 80,000. Then 120,000.

Screen shot at 9:49 (11:49 CST)

A few minutes before midnight, Senate President Dewhurst called a vote to end the filibuster. Doing so required ignoring parliamentary procedure and, specifically, ignoring Sen. Leticia Van de Putte, who had already moved to adjourn in order to block said vote. She argued that he had ignored her; he replied that he hadn’t heard her. Sen. Van de Putte, desperate for parity, asked, “At what point must a female senator raise her hand or her voice to be recognized over her male colleagues?”

The crowd erupted. The noise was incredible. The number of YouTube viewers rose. The live feed remained focused on the senate floor, but there was no mistaking the presence of hundreds of people in the gallery. After midnight, when I found other videos, I saw that the entire capitol building was packed to the rafters with Texans supporting the filibuster. More were outside. The cheering went on for a few minutes, and then a few more, and then it was clear that, ten minutes before the end of the session, they weren’t going to stop. President Dewhurst and his GOP colleagues had cheated—boldly, over and over, in front of a whole mess of Texans. And, as he should have known, you don’t mess with Texans.

Screen shot at 12:05 CST. The gallery was still going crazy

There is much more to the story: Misogyny and racism are still pervasive in U.S. politics. Social media had an incredible impact on the outcome of this session. All of this is to say that this particular senate session was small-town politics writ large. I saw unfair things play out many times when I lived in the Columbia River Gorge. People in power sometimes feel like they can get away with things. Sometimes, they even feel like they deserve to.

June 23, 2013

Is Homemade Jam a Bargain?

There is no doubt that organic homemade jam can be exponentially better than store-bought jam. But is it cheaper to make? I decided to do the math.

Since I’m currently gardenless, I had to buy my berries. Without even getting out the calculator, I’m going to guess that this is the deal-breaker for my batch of jam. If I were still in White Salmon picking berries from my own established beds, the only expense for them would be water and my time (and lord knows how much that is valued in today’s economy!). Anyway, the flat of organic berries (approximately 12 pounds) cost $27 from my friend Nellie, who sourced them from a farm that pays its workers a fair wage yada yada.

Thanks, Garcia Farm!

Oregon strawberries are spectacularly flavorful and tender. They are also, not coincidentally, fragile. They begin to deteriorate immediately once off the plant. Since I was unable to pick my flat up for a couple of days, I lost at least a quarter of them to rot and bruising. That left approximately 9 pounds to work with.

I went to one of Portland’s dozens of “natural” groceries and bought pectin, made from citrus peel and requiring half the sugar of conventional pectin, and organic cane sugar. The pectin cost $5, and the sugar (4 pounds, of which I used about half) cost $6.

I went to one of Portland’s dozens of “natural” groceries and bought pectin, made from citrus peel and requiring half the sugar of conventional pectin, and organic cane sugar. The pectin cost $5, and the sugar (4 pounds, of which I used about half) cost $6.

I already own canning equipment, but let’s say I had to buy new lids: $2. And let’s say about $10 in water, electricity and gas to cook and process the jars. I have amortized the original cost of my equipment to the point of not including it. And then there’s my time again … about two hours.

My yield was 7 pints in 8-ounce (half-pint) jars, so:

Strawberries $27

Pectin $5

Sugar $3

Lids $2

Power $10

Total $47

That’s $3.36 per jar. A quick internet search produced Ikea lingonberry preserves on a discount website at $8.47 for 14 ounces. My jam actually came out all right! If I had access to a free berry patch, it would be even cheaper, just $1.43 per jar.

But I guess Ikea jam could be considered kind of fancy, so I kept looking. I found Smucker’s strawberry (conventionally grown, high-fructose corn syrup, chemicals aplenty) on sale at a corporate grocery store at $2.50 for 32 ounces! I guess organic can’t compete with that. On price, anyway.

My family would rather go for quality, not quantity. So, now I will enjoy my jam—not only for the satisfaction of making something and its high-quality ingredients and delicious taste, but also for its relative cost-effectiveness!

June 16, 2013

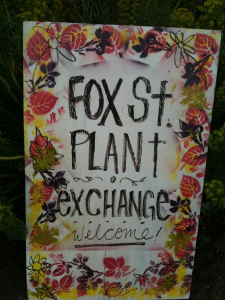

Nurturing a Neighborhood, One Plant at a Time

Not long before Mike and I left our St. Johns neighborhood in 2003 to move to the country, we were invited by friends Rachel and Greg to a fun party—a plant exchange! The idea is, you pot up your extra tomato starts and the like, and then trade for starts you don’t have. We were unable to attend, and then we moved away. Upon returning to Portland, I learned that the plant exchange was still going strong. In fact, like the plants, it had grown!

St. Johns is one of those areas city planners like to call “transitional.” A small town in the late 1800s, it was annexed by Portland in 1915. Most of the neighborhoods built thereafter housed dock workers on the nearby Willamette and Columbia rivers—the homes are modest, mostly one-story Craftsman-types with tiny bedrooms and simple yards. The second wave of people who owned them, in the 1950s, upgraded them as per the era: painted woodwork, carpeted floors, chain link fences, aluminum window awnings, and lawn, lawn, lawn. Our house, when we moved in, even had one of those wooden wishing wells in the backyard. The recession of the ‘80s resulted in many of those homes falling into disrepair, and St. Johns is still working to pull itself out of that funk.

St. Johns is one of those areas city planners like to call “transitional.” A small town in the late 1800s, it was annexed by Portland in 1915. Most of the neighborhoods built thereafter housed dock workers on the nearby Willamette and Columbia rivers—the homes are modest, mostly one-story Craftsman-types with tiny bedrooms and simple yards. The second wave of people who owned them, in the 1950s, upgraded them as per the era: painted woodwork, carpeted floors, chain link fences, aluminum window awnings, and lawn, lawn, lawn. Our house, when we moved in, even had one of those wooden wishing wells in the backyard. The recession of the ‘80s resulted in many of those homes falling into disrepair, and St. Johns is still working to pull itself out of that funk.

Rachel and Greg’s house is close to Pier Park, one of Portland’s original city parks that dwarfs the adjacent neighborhood with majestic Douglas firs and cedars. Their landscaping blends right in—they’ve replaced all of that lawn with an incredible naturescape of native plants and gravel paths, essentially creating a mini-park of their own. Greg’s previous job had him on major construction projects, so he made a habit of rescuing native plants as they fell to the bulldozer’s blade. The yard is resplendent with fringe cup, fern, rhododendron, Solomon’s seal, and even hard-to-transplant poet’s shooting star.

Rachel (right) admires Zoe’s face-painting handiwork–she did it ALL BY HERSELF!

Greg talks about native plants in the side yard

These days, Rachel starts preparing for the spring event the previous fall, potting up extra growth from her yard. “Our goal is to populate St. Johns with native plants,” she says.

Bring home one of these little pots of fringe cup …

… and you might have this in a few years!

After 11 years, there are dozens of people on the mailing list. They trickle in and out over the weekend, rain or shine, bringing everything from lettuce starts to massive stands of bamboo. They come with baskets, wheelbarrows and little red wagons. The yard is full of kids, swinging in hammocks and decorating their faces at the painting station. The grill is going and bottles of wine are open.

As they spread plants around the neighborhood, Rachel and Greg also spread neighborliness.

June 9, 2013

Guest Post: Living a Local Life

I met poet Penelope Scambly Schott at the Columbia Center for the Arts’ annual Plein Air Writing Exhibition. Her work became some I looked forward to most. I learned that she lived in Portland but was spending a good deal of time in Dufur, a tiny town about 40 miles east of Hood River. She recently published a book of poetry dedicated to her half-time home.

Living a Local Life

By Penelope Scambly Schott

I’ve been thinking about what constitutes a local life.

As for me, I live two lives, one on a hill in Portland, Oregon, about four miles from the heart of downtown, and the other right next to the K-12 school in Dufur, Oregon, population 600, on the dry side of Mount Hood in a valley embraced by wheat fields. In Portland I go to theater and attend poetry readings; in Dufur I attend the threshing bee and go every Thursday evening to the knitting group at the school and community library.

Yes, I have had previous lives. I grew up on the upper west side of Manhattan and spent my childhood at the Museum of Modern Art and Broadway shows. I spent 30 years outside Princeton, New Jersey, among the intellectually pretentious before I moved to Portland where I learned the word “spendy” for what is overpriced or ostentatious. Three years ago, in a conjunction of circumstances, I bought this small house in Dufur, and every week from Thursday to Saturday I come out here to write.

I am telling you a love story. When I started coming here, I had various other writing projects but I kept interrupting myself to wander about with my dog, Lily, and then go back to my house and write poems about Dufur. This spring Windfall Press–which is concerned with “poetry of place”–published my book Lovesong for Dufur. The collection opens with the meadowlark announcing Spring up on “D” Hill, runs through all the seasons, and ends with my buying a plot at the local cemetery and discovering that “I have never been happier.”

Penelope and Lily on top of “D” Hill above Dufur, Oregon (photo: Margaret Chula)

I recently gave a reading from my book at our local historic hotel, the Balch, which was built in 1907 from bricks made right here in Dufur. Samantha, the current hard-working owner, served fruit and cheese, and there was a cash bar but almost everyone drank the free water. My many Dufur friends, and some of their friends, came to hear me. As far as I know, nobody in that crowd had ever attended a poetry reading before. I have no idea what they were expecting. My publisher read a few poems from his own book and then introduced me to the waiting crowd that already knew me.

I began with the dedication to all my local friends. In my second poem, “How to Move to a Small Town,” I described a return trip to the local hardware store and read the line, “Let Molly the owner be there drinking coffee.” Well, everyone cracked up. I guess I was just about the only one in the room who didn’t know that Molly is usually drinking beer. I read about the grain elevators, the local sewage plant, the food bank, the nun with six cats–Sister Patricia was there and corrected me; she’s up to nine cats. I concluded with a poem:

Do You Want to Visit Dufur?

Is the world too much with you “late and soon”

as the poet Wordsworth complained?

Call the hotel. It’s the Balch. Or email them.

We’re quite modern:

up on “D” hill, we have many fancy antennas

between the cows.

The Balch boasts running water in every room.

And steam heat.

When the hotel opened in 1908, it had electricity

twelve hours a day–

at night when the Dufur sawmill wasn’t using it.

These good solid bricks

were made right near here on Mr. Balch’s ranch:

three stories of Italianate brick.

Salesmen who rode the Great Southern Railroad

set up their wares in the parlor

Witness this big black safe standing by the wall.

Don’t try to unlock it.

Rest assured. Whatever you want is safely there,

I promise.

Though the knobs conform to fingers long dead,

you are still breathing.

See what Dufur can do for you.

It’s our town motto.

People loved it. They bought multiple copies of Lovesong for Dufur to give to their children who had moved out of town. It was a great evening. After signing a bunch of books, I went home and served Dufur sausage casserole to seven people. Now, that’s local.

June 2, 2013

Get Your Country On!: The Official Workshop

Bring me to your leader!

I have something new to share: a companion workshop to Get Your Pitchfork On! As I mentioned in a recent post, I had a fun first year presenting Get Your Pitchfork On! to bookstore audiences across the country. Now, I’ve created a workshop for both large and small groups.

Last weekend, a dozen generous souls suspended their Memorial Day weekend plans to join me for beer and chili, and a practice run of “Get Your Country On!”

Thanks Joe, Shari, Leah, Rebecca, Bill, Evan, Judith, Karla (pictured) and Suzy, Ryan, Mike, Laura

This presentation is interactive; participants break into small groups to discuss their own ideas of what a perfect rural life would entail. People who are contemplating a move to the country have already thought of a few contingencies. “Get Your Country On!” brings up things they probably haven’t.

For example:

• Microclimates and other landscape issues

• Environmental hazards like road spray and orchard smog

• Cell phone coverage

• Culture shock

• Pervasiveness of death (not yours! of plants, insects and animals)

Feedback from this practice run was great; I have incorporated it and am ready for my first prime-time showing—today at the Mother Earth News Fair in Puyallup, Washington!

I would love to discuss the joys and pitfalls of country living with you!

Later in June, I’ll present “Get Your Country On!” at Regards to Rural, in Corvallis.

A reader recently said of the book: “You’re doing a great service to people. If I were considering a move to the country, your book would save me a ton of time and money. For those on the fence, it would certainly help answer the question of whether it’s the right move or not.”

Do you have a gardening group, CSA, book group, farm-to-table event, community education class or other opportunity for “Get Your Country On!”? Please check out my website or contact me at kristy @ kristyathens.com.

May 26, 2013

Julie Green’s “The Last Supper: 500 Plates”

I used a recent lunch hour to visit Marylhurst University, the latest stop for Julie Green’s installation, entitled “The Last Supper: 500 Plates,” which quietly protests the United States’ practice of capital punishment by commemorating final meal requests made by death-row inmates.

Green represents each inmate put to death by the government with one second-hand white plate on which she paints the meal that inmate requested. She has vowed to continue this meditation until capital punishment ceases to exist.

Walking into The Art Gym, Marylhurst’s gallery, I was taken aback at the sheer number. I know “500 Plates” is part of the title, but wow. On some walls, they were neatly organized in groups and on others they seemed to stretch from floor to 12-foot ceiling.

I have no idea how this photograph got on my phone

Over loudspeakers, I heard what I assumed was Julie Green’s voice reading from a list of meals: “Texas, 18 September 2001: Western omelette, fried potatoes, sliced tomato, pan sausage, three biscuits, white gravy, pitcher of vanilla milkshake, half a cantaloupe. Texas, 22 October, 2001: One bag of assorted Jolly Ranchers.”

The source of the audio turned out to also be a video. Someone placed one of the artist’s plates onto a black surface, square in the camera’s overhead frame. Green read the contents of the plate, and then the frame faded to black. Over and over. The presentation was brilliant, a disembodied hand placing each last meal before the viewer.

I had to wonder: “How did they decide what to ask for? How could they possibly finish their meal, or even eat at all? How long do they have to consume the meal?”

I was grateful I’d eaten lunch before going to the exhibit.

As Green points out in an interview, food is one of the few things people truly all have in common. Some of the inmates were limited by rules or statutes to certain types of food—in California they have to order “fast food;” in Texas they would get hamburger if they ordered steak. Some requested extravagances; some ordered the same meal being served in the prison; some refused food altogether.

Regardless of what the viewer feels about the idea of capital punishment; whatever these people had done to earn their fate; Green succeeds in humanizing them, one plate at a time.

May 19, 2013

Sou’Wester!

Let me start by saying I do not recognize Oregon this spring. First, we had a couple nice days in April. Like, in the 70s. That happens sometimes; not a big deal. But we usually dive back into overcast misery. Not this year! While it’s been snowing in my native Minnesota, in the Willamette Valley we’re into Week 4 of unprecedented weather.

A recent weekend was outrageous. It was almost 90 in Portland. It was in the 80s on the coast! It’s never in the 80s on the coast. If you’re not familiar with it, the Oregon Coast is a place where people occasionally surf—in full-body wetsuits. The water temperature hovers in the 50s, or colder. It is a scenic gem, but not the Jersey Shore.

Last Sunday, when my husband Mike and I pulled onto the beach at Cape Kiwanda State Park around 3 in the afternoon, the thermometer in our car read 86 degrees. Cloudless sky. Outrageous.

Doomsday global-warming theories aside, we were pretty thrilled about it

As the wind was huffing from the north, Mike parked the car perpendicular to the shoreline. We set up on the south side of the car: Beach chairs, cooler, wide-brimmed hats. We brought a blanket but since the wind was blowing loose sand in waves like you see in nature films of the Kalahari, it was better to be a couple inches off the ground. Every once in a while, the air would kick up a sandstorm—we would tuck in and wait for a few seconds.

The tide was out, so there was a vast expanse between the shoreline and the dry, loose sand. Everyone was parked more or less in a line, on the hard-packed sand furthest from the water. If you got too far into the soft sand it would be hard to get out without 4-wheel drive. Of course, that didn’t stop people trying. Every once in a while, someone felt a little saucy and purposely whipped around in that loose sand like Jim Rockford. I could hardly blame them; when else does one get to use a Jeep like a jeep? The beach seemed the perfect size to allow everyone to have their own space.

Our lil’ slice of heaven … about 20 minutes pre-Sou’wester

The part of the beach that allowed cars was about a mile long; we drove about halfway down to park. Many cars had gone all the way to the south end of the beach, which required fording some shallow streams. Bordering that end of the beach was Cape Kiwanda, about 1,000 feet high. It made a nice focal point to the scene, towering over the little cars clustered at its base. On its opposite slope was the inlet that houses Pacific City. Further out into the water, Haystack Rock ignored the wind, the crashing surf and everything else.

We ate a little lunch, walked down the beach and back, climbed a bluff to see what was up there (just a road), and sat in the sun. After a while, we got tired of the water being so far away and carried our chairs out to a rivulet that was coming in parallel to the shoreline. It filled and emptied as waves crashed nearby. This water, being in a shallow channel, wasn’t as cold. But still plenty cold. I had to pull my feet into the air occasionally to let them warm up.

Any time the tide is out simply means it is going to start coming in again. As we ate our dinner, the little stream we’d had our chairs in became a river, and then disappeared altogether as the tide crested the small wall of sand that had created it. We’d also noticed a thin line of weather on the horizon. Clouds started piling up in the south.

“Look!” said Mike, who faced them. I turned to see that Pacific City was completely fogged in all of a sudden.

“That’s weird,” I said, and then noticed that fog was starting to pile up in front of the cape and Haystack Rock.

Then, it started reaching over Haystack like giant grey claws.

We gaped in awe; it was as though we were watching one of those fast-forward nature shots. The clouds moved at unreasonable speeds. The wind shifted and started coming from the south; the temperature dropped 20 degrees in an instant.

We wondered if this was how people behaved when Vesuvius erupted—simply staring at it coming, in slack-jawed disbelief. (Neither of us had the presence of mind to take a video …) Haystack was gone. The cars on the far end of the beach were invisible except for their headlights. We looked over and saw that the tide had surged; the water had turned steely and was blowing straight into the air. The egress of the cars on the south end of the beach was under water; they raced to cross at the most narrow point. A neighbor up the beach struggled to get his VW pop-top camper down before the wind ripped it off completely.

Mike ran to the driver’s side to close the windows. Sand stung my shins and face as I finally accepted that our beautiful day was over and this thing was coming our way—fast—and started folding up our chairs. The wind blew everything against the car, so we wrestled with our fold-up lawn chairs to get them into the trunk.

The whole thing happened in about three minutes. Easily the craziest non-human thing I’ve seen in real life.

We ducked into the car and laughed. It was so ridiculous! It had happened so quickly! But it had indeed happened. And we were not out of danger. The sun was gone; no sky, even—we were enveloped in this crazy storm. The ocean was blowing sideways; breaking in lopsided angles and surging ever closer to our car. All the hard sand was submerged; we had to bushwhack through the soft sand to get out.

As we pulled onto the highway, I checked the temperature. 61. A real, live Sou-wester had gotten us. I imagined experiencing that storm in a boat. Outrageous.

May 12, 2013

Guest Post: Is Jackson Hole Rural?

My friend Meg grew up in Jackson, Wyoming, and then flew the coop as a young adult to become a world citizen, living in New York; Portland, Oregon; and San Francisco. She returned to her hometown a few years ago. I took advantage of my Get Your Pitchfork On! book tour to visit her last September.

We met when she lived in Portland because we’re both writers, and used to have epic walk-and-talks—we’d go up to Forest Park and cover miles while energetically debating current issues. We were excited last fall to get back to our old routine! One of the topics we considered was comparing “urban” and “rural.” I had referred to Jackson Hole as a rural place, and she demurred.

Hmm, a boardwalk … rural?

“How do you define ‘rural’?” she asked. I thought it was an odd question—I mean, look around! Mountains. Livestock. Moose. However, I was asked twice more during my stint in front of the Valley Bookstore, hawking copies of GYPO and chatting with passers-by. “What do you mean when you say ‘rural’?”

My definition at the time related to population and proximity to an urban area. Jackson is a small, remote town. Isn’t that rural? To me, it has nothing to do with wealth/poverty or “sophistication.” But the question remains: What does “rural” mean, exactly? Here’s Meg’s take:

Is Jackson Hole Rural?

by Meg Daly

At the risk of sounding too relativistic, it depends on whom you ask?

Certainly my friends from unequivocally urban areas like West Hollywood or North Portland will encounter “rural” in all its cow-dotted, mega-cab-truck splendor. But many of us who live here espouse non-rural cultural values and interests one would expect to find in abundance on the funky streets of Williamsburg, Brooklyn. We zip around in Priuses or (gasp) on bikes, listen to Vampire Weekend, and read articles about gastronomy and modern design.

Setting aside definitions of rural and urban based solely on population density and open space, and looking instead at values and aesthetics, then Jackson Hole is actually a little Petri dish of urban and rural in constant state of tension. The town’s main industry is tourism, and in the summer that means millions of visitors from all backgrounds coming through to see “the last and best of the Old West.” In the winter, however, tourists flock to Jackson for world-class alpine skiing, and they want the luxe amenities they’ve come to expect in cosmopolitan settings.

I think it’s a sign of the urbanization of the world. Much like globalization, the landscape is being flattened so that the texture and personality of rural America becomes a commodity rather than a place or way of life. In recent years, my town has endured heated debates about planning and development of the few remaining open spaces. Opponents to development started a campaign called “Don’t Let the Hole Lose Its Soul.” Proponents speak to the need for affordable housing, with the pragmatic view that open spaces tend to get developed eventually so why not do it in a thoughtful way.

Our local debate raises questions about who gets to be the representative of a town’s “soul.” In a little mountain town like Jackson, with severe winters and a super-short growing season, people have only been living here year-round for a century. The town has changed in personality with every passing decade. Why shouldn’t Jackson Hole become a place where skateboarders and cowboys ride?

On our main drag, Broadway, the Jackson Hole Historical Museum (where you can view an exhibition like “Homesteading the Hole: Survival and Perseverance”) abuts Nikai Sushi (where you can sip a Lotus Flower Martini while noshing on a Big Kahuna roll). These kinds of juxtapositions exist all over Jackson Hole. I’m less concerned with whether Jackson qualifies as rural or urban, or whether we lose or protect our so-called soul. I see Jackson the way I think people have always seen it, for better or worse, as a new frontier. The challenge is to be pioneers on that frontier, and to create healthy, vibrant communities living in balance with nature.