Kristy Athens's Blog, page 10

May 5, 2013

Gone Fishing

Sometimes you want a big party on your birthday, and sometimes you just want to get away from it all. This was one of the latter years for me, so my husband Mike and I drove up to Wallowa County, Oregon, to visit our friend Jon and get some R&R.

This is not Jon’s first appearance on this blog—I wrote about his fancy firewood bundles last summer in my value-added marketing post.

We arrived late Saturday. Tucked into a corner of our guest room was a work table laden with shiny streamers and baubles, tools and small drawers—a fly-tying station. Jon is an avid fisher—and why wouldn’t you be when you’re a short drive (country-short, at least) from dozens of pristine mountain rivers? He promised to take us to a friend’s ranch on the Imnaha on Sunday and give me a fly-fishing lesson. The last time I fished was in about 1978. I barely remember it.

The next morning, we packed a lunch, fishing gear and the dogs into the pickup and took off.

Getting to Imnaha is a commitment—it’s 45 minutes from Enterprise, nearly on the edge of the state. As we drove into the Wallowa Mountains, snow flew. I looked out the back; the dogs were unfazed by the crust they were acquiring. Mike and I looked at each other. This was going to be some chilly fishing! But by the time we passed between Inmaha’s two buildings we had dropped a couple thousand feet. The sky had cleared and the temperature had risen at least 15 degrees.

But we weren’t there yet. We turned north for about ten miles, following the Imnaha River, until we ran out of pavement. Then we drove another ten on gravel. This road twisted up and into the mountains, around blind hairpin turns that revealed incredible views of the Imnaha River valley. We were so remote that we came across two bighorn sheep in the road! The dogs had already shaken off their snow-jackets and ran from side to side in the cab, anxious to explore.

Eventually, we wound down to the river’s edge. Jagged peaks rose up all around the narrow, grassy river valley we were in. The Imnaha ran hard and fast, swollen with spring snowmelt. Jon jogged down to survey the water and returned to get the gear. I would have drowned in his hip waders, figuratively if not literally, so I fished from shore.

Scouting from the bank

What we were hoping to coax out of this cold, turgid river were steelhead. These rainbow trout act a bit like salmon—they swim hundreds of miles down the Imnaha, then the Snake, then the Columbia, all the way to the ocean, and then fight their way upstream all the way back a couple of years later to spawn and die. Jon works for a rafting outfitter and has documented a number of his catches. Did I mention that he is a great writer?

First Jon introduced me to the fishing gear. I had already declined the waders, but was totally fascinated by the little box of flies he’d tied.

“You’re basically trying to drop something into the water that looks like food,” Jon said. Fish look for sudden movement, and dark and light patterns. The nymphs had shiny bits to catch the light, and fuzzy bits that would clump in the water and look like little insect bodies. He said that pink was good during spawning season. “Mine are showy,” he said, pointing out the features of his nymphs.

This one was made with deer hair

Jon explained how the fly rod works, a different technology from a standard rod-and-reel. Of course, the rods themselves are much longer, to aid in casting. Instead of relying on lead weights to give the hook loft, the line itself has weight. And there are little weights that you can put on your hook, called “heads.” Even with a head on your hook, it doesn’t weigh much, which is why fly-fishers actually get in the water on a wide river. (Plus, it’s fun to stand in the middle of a river.)

Some of the differences are purely aesthetic—the floating, round ball attached to the line that you watch to see if it dips into the water? “A bobber!” I said, proud that I knew something. “A strike indicator,” Jon corrected, and then proceeded to call it a bobber anyway.

Next lesson: Where to cast. He explained that fish like to hang out in calm water that isn’t too shallow; they avoid the strong current and the edges. What we were looking for, he said, was “soft” water, called the “seam.” Looking out, I could see a place where the top of the water smoothed out for about 20 feet. The seam.

The method of casting differs as well to accommodate the lighter bait and longer rod. The fly-fisher is nearly constantly in motion. Some people consider it an art form. Dry flies actually rest on the surface of the water to emulate flying insects landing. Even wet nymphs need to move often.

But Jon is a pragmatist; if there’s no need to do it fancy, don’t.

“Have you ever seen A River Runs Through It?” he asked me.

“No.”

“Good.”

Subsequently, I was not being taught to whip the line around in the air like a lariat.

As Jon explained the timing of pulling the nymph back for another cast, Mike, who was observing from further up the bank, yelled, “Your bobber!” While I had been looking downstream, following Jon’s illustration, a fish hit my fly. But the fish recognized the fly wasn’t food and, since I hadn’t pulled up to set the hook, spit it out.

I kept casting, trying to focus on my form. After a while, Jon joined me—and then his rod snapped in two.

Sad fisher man

Since I was the only one doing anything, I practiced my cast a few more times and then called it quits. We went back to the rig and ate lunch in the sun. The scenery was so spectacular that is was difficult to leave.

Picture, do the talking

Jon was disappointed that we didn’t catch anything; I wasn’t. I completely understand the notion that going fishing can just be an excuse to be outside all day! It was exactly the kind of birthday I was hoping for.

April 28, 2013

Behold, the Cow

Get Your Pitchfork On! came into the world a year ago. And what a year it’s been! I spent most of 2012 traveling around to promote the book, which gave me an excuse to visit family and friends.

It was important to me, while writing the book, to make it not about me. I wrote it for you, the reader, and your dreams of living in the country. In spite of that, I sometimes found it difficult to completely divorce myself from the emotional ties I still have to that little parcel in Washington. I learned the hard way that if I read the line from the book’s introduction, “Our beloved dog had been killed on the highway bordering our property,” I’d choke up if there was someone in the audience who knew her.

Reading the introduction to the Land section, in which I describe the most wonderful features of living in a remote, natural area, had a similar effect. I often dug a fingernail into my thumb to keep it together.

Despite this, and despite peppering my presentations with cautionary tales of cats being eaten by coyotes and homesteaders putting their arms in wood-chippers, I tried to keep it fun! One of my efforts in this regard has been the menagerie of farm animals I’ve set up on the podium in front of me. These plastic toys have been a big hit, to the point that I’ve had to keep an eye on children passing by my table at book fairs—they hope they’re giveaways.

These animals came to me in the best possible way, just a couple of months before GYPO hit the bookshelves. I was at a Portland bar known for its fantastic Happy Hour—cheap and delicious food, and an always-changing champagne cocktail special. My friend Anmarie and I met there and ordered the special, which was some crazy thing involving elderberry liquor from Switzerland or something. To our delight, the bartender had topped each flute with a farm animal; mine sported a goat and Anmarie’s a horse. Naturally, we had to order another round, and scored a cow and a chicken. Anmarie graciously surrendered hers when I decided that I would bring them to every book event.

My first reading was, appropriately, in the Columbia River Gorge, where Get Your Pitchfork On! was born. I traveled all around Oregon and Washington, and even made it down to Los Angeles and over to Wisconsin and my home state, Minnesota. These were wonderful opportunities to see many dear friends of past and present all at once. And I also got to have great conversations with people I’ve never met, and will probably never see again.

As you can see from my schedule, I did not stick solely to bookstores! That first reading was in my friends’ restaurant, Solstice Wood Fired Café (with support from Waucoma Bookstore). I set up a table at a plant nursery in Salem, Oregon, a winery tasting room in Jacksonville, Oregon, and a feed store in Portland. I had a lunch talk in a little diner in Waupaca, Wisconsin. I read in bars in Portland and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I got to share my stories with a couple dozen relatives—and my high school prom date’s parents!—in my dad’s hometown of Appleton, Wisconsin, on his mother’s birthday.

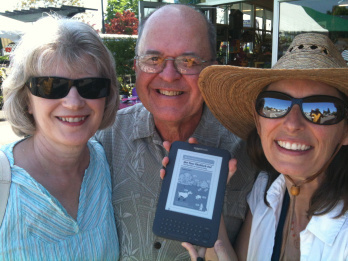

Hawking my wares—a great way to spend a day outside

I signed a post-it note for my friends Betty and Rich’s e-reader

My Grandma insisted on letting me horn in on her birthday cake

Not everyone gets to sit in the Red Chair of Wordstock

In January of this year I was part of a panel discussion put on by Laura Stanfill, who had interviewed me after GYPO came out, and then included that interview in a book about writing called Brave on the Page. At a long table at Powell’s, as per usual, I set out my farm animals.

The panel’s moderator, author Joannna Rose, handled the group expertly—she asked great questions and threw in the right amount of humor. At one point she interrupted herself to ask me, “Why do you have those animals in front of you?”

Later, Laura sent me some photos she had taken, including this one, which she titled, “Behold, the Cow”:

“Behold, the Cow” by Laura Stanfill

What a fun year! Thanks to publisher Adam Parfrey and Process Media’s staff, particularly Carrie Schaff and Jessica Parfrey; publicists Mary Bisbee-Beek and Sheepscot Creative’s Dave and Bethany; blurbers Mark Wunderlich, Kim Barnes, Corinna Borden, Monica Drake, and Frank Bures; designer Gregg Einhorn; and the chapter-readers and everyone else noted in the book’s acknowledgements. And everyone who’s come to an event and/or bought a book.

Happy First Birthday, Get Your Pitchfork On! May you have many more—there are lots of people I still need to visit!

April 21, 2013

The Death of Thrift-Store Shopping

Growing up, my family didn’t have a lot of money. We’re innate treasure hunters. And Catholics.

This all added up to a particular tradition from my childhood: On the way home from Mass, my mom, sister and I would zigzag across the western suburbs of Minneapolis and hit every yard sale we could find. It was a win-win: my sister and I felt like we were getting new things; my parents spent a couple bucks, max. I still have a small train case that I bought for 25 cents.

When I got older, thrift shops became a Thing with my friends and me. Even though we went to an upper-middle-class high school and could have shopped at Benetton, Laura Ashley, or a new store called The Gap (I had a waitressing job by then and could buy my own things), it was the mid-1980s and we were into New Wave music. We preferred the punk rock aesthetic of military surplus and second-hand clothes from the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Some thrift shops were in church basements, some in flagging strip malls. The coolest option was a sort of combination military surplus and vintage shop called Ragstock. My friends and I spent hours there, trying on cardigan sweaters and combat boots. We could score embroidered bowling shirts, old men’s plaid golf shorts and Navy pea coats—all super-cheap. Our parents were aghast that we sought out their parents’ fashions … on purpose.

Twenty-five years later, I still love to scour yard sales for good deals. The trouble is, the good deals are becoming harder to find. There are two factors at work: taste and quality.

Mid-century people owned a few, quality things, and they had “Sunday best.” They also dressed up more, generally. Have you ever seen a photograph of a crowd at a baseball game in the 1960s? Men wore hats (I mean HATS, not baseball caps). Women wore them, too, as well as dresses, gloves and heels. My grandfather wore a tie every day, even when he never left the house. Blame the pantsuits of the 1970s; fashion has become increasingly casual. Nowadays, some people even go out in public in pajama bottoms and extra-large t-shirts.

Another factor is the plain old passage of time. In 1987, there were thousands of ‘60s shirts in existence. Decades later, they have simply been worn to pieces. No new ones are entering the thrift store stream. Subsequently, what ends up in thrift stores is not pristine Pendleton wool shirts and pleated skirts. Those things now end up in vintage shops.

Vintage and thrift shops used to be basically the same thing; now they’ve split so that those high-quality pieces of yore are not just old clothes, but also rare and unique clothes. And because of Internet sales, discarded clothes don’t stay in their community; they’re scooped up by jobbers and resold everywhere. So, now you find things for sale like this $200 cape.

Even Goodwill high-grades their designer labels. So, you might find an Armani suit there for $150—still a bargain considering it’s an Armani suit, but also still $150.

I knew a guy in Hood River who’d made a deal with estate sale managers in Eastern Oregon—he got the first go at everything they ended up with. He happened upon a stack of 1950s brand-new Levis from the storage room of an old outfitter and, instead of selling them locally, posted them on Ebay, where he said Japanese shoppers were laying down $300 per pair!

Many modern thrift stores also buy batch lots of cheaply manufactured, new clothing from wholesalers, which is why you might see six of the same shirt on a rack. Or, this new leather jacket. $165.

[image error]

New jacket in a “thrift” store

There is still the occasional exception. During my two-month writers’ residency in 2010 in Harney County, Oregon, I happened upon this beautiful wool, fur-collared coat at the thrift shop.

[image error]

“Oh—you didn’t!” “Merry, Christmas, Honey. I got a good price on the cattle this year.”

It was most likely a very special gift from a rancher to his wife. She most likely only wore it for Christmas and funerals. It’s in perfect shape, and I paid five dollars for it. Five.

Urban vintage shops are usually run by people in their 30s, and guess what they think is ironic and cool—‘80s stuff! Not what my friends and I had, but actual things sold in the ‘80s. The dresses my teachers wore. The neon sportswear. The foot-torturing pumps. I’m just waiting for shoulder pads and those face-shield eyeglasses to come back. For they will.

I traveled a bit last year to promote Get Your Pitchfork On! and hit thrift shops wherever I could. Proof that I am, deep down, an optimist: Every time I approach a new thrift shop I think, “THIS one is going to be awesome!”

But they never are anymore. I went to Los Angeles and thought: Okay, movie stars must dump their fabulous clothes. They do, it turns out. But those thrift shops sell things for triple-digits, and the women’s clothes are tiny (anorexic-tiny, not short-tiny). I went to Jackson, Wyoming and thought: Okay, these people are rich! But even rich people wear regular clothes, apparently. I tried remote locations, such as Appleton, Wisconsin, and Hermiston, Oregon, in hopes of some old-school quality. Same deal.

Water, water, everywhere, and not a drop to drink

It’s over, punk rock children of the ‘80s. We’ve had a good run. Thanks for the memories!

April 14, 2013

Agriculture and the Media

Friday morning, I biked to Portland’s EcoTrust building for a conference that I learned about just last week at a Friends of Family Farmers event: Food+Agriculture Media Project. The idea was to get food and ag journalists, editors and researchers together to talk shop, meet each other, and maybe learn a few things along the way. I did all three!

The keynote speaker was from American Public Media’s Marketplace program, Adriene Hill. She talked about the challenge reporters face in trying to keep issues like organic food and global warming fresh to a weary audience. If a story about global warming leads with the subject itself, no one hears the story—the people who agree with the idea pat themselves on the back and turn off the story, and those who don’t agree curse at the radio and turn off the story. But, she continued, if the story begins with the price of chocolate going up everyone listens, even as the cause is identified as global warming.

Food, Hill noted, is uniquely suited to lead into any number of topics. “Everyone eats,” she said, “so everyone can relate on some level.”

After a few presentations about storytelling and the necessity of multimedia platforms, a panel convened to discuss the subject of raising and eating meat. The panelists considered a number of angles of meat production, discussing the cost of raising and processing grass-fed beef and compassionately raised poultry, and how that cost consigns the farmer to meager profits and precludes many from being able to afford it.

They also talked about the utter failure of the federal Farm Bill to meet the needs of mid-sized farmers and ranchers. Microenterprises and, especially, corporate industries fare much better, in the latter case to the detriment of vast swaths of land as well as people. A rancher from Eastern Oregon remarked that if direct subsidies from the Farm Bill were reinvested in conservation efforts, the landscape would “change overnight.”

What was sort of amazing—exciting and daunting at the same time—is how clear everyone is about how no one has all the answers, and they’re also not sure how to collect and assemble them. The Big Picture, it turns out, may be altogether too big for any single person to comprehend. As I contemplate future projects in the world of agriculture and rural life, it’s both a challenge and an opportunity.

April 7, 2013

Guest Post: From Field to Table

Ed Battistella’s greatest achievement, as far as I’m concerned, is that in 2012 he made up and posted a new English word every day on his Twitter account, @LiteraryAshland. In September of last year, he interviewed me about country living and book-writing for his blog, Welcome to Literary Ashland. Ed teaches at Southern Oregon University and is working on a book about the linguistics of apology.

From Field to Table

By Ed Battistella

Reading the section on animals in Get Your Pitchfork On (and especially the chicken idioms on page 136) got me to thinking about the way we refer to animals and food, and reminded me of this recipe for giblets from a 15th-century cookbook:

Take fayre garbagys of chykonys, as þe hed, þe fete, þe lyuerys, an þe gysowrys; washe hem clene, an caste hem in a fayre potte, and caste þer-to freysshe brothe of Beef or ellys of moton, an let it boyle; an a-lye it with brede, an ley on Pepir an Safroun, Maces, Clowys, an a lytil verious an salt, an serue forth in the maner as a Sewe. *translation below

Recipes like this give us some clues to Middle English relationships with food and animals, and our own. The word for giblet was garbage, a precursor of Modern English, and in Old English (no e on Olde!). In Old English, mete meant food (as in sweetmeat, mincemeat and nutmeat) and the word flæsc (flesh) was used for animal-tissue food (check out your handy Oxford English Dictionary). And people ate animals, not meat: they ate picga (pig), sceap (sheep), cu (cow) and cíecen (chicken).

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, many French words were borrowed into English, resulting in the possibility of more than one way to say things. The French introduced words for the cooked forms of animals: pultrie (poultry), porc (pork), motoun (mutton), boef (beef), and veel (veal), as well as garbage and gysowrys, both meaning the edible entrails. The two levels of vocabulary allowed speakers of English to eventually separate the farm from the table—the cooked form of animals, the product, was rendered in French, while the field form was from Old English. But throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, boef and motoun were used as terms for the animals as well as for their meat (of flesh). The distinction between French terms for food and English terms for animals doesn’t get fully baked in until early Modern English (Shakespeare refers to the “flesh of Muttons, Beefes, or Goates” in the Merchant of Venice) and modern ranchers still sometimes refer to cattle as beef.

Bon appetit.

I love me some cíecen … I mean pultrie …

*Translation of above in Modern English: “Take good garbage of chickens, as the head, the feet, the livers, and the gizzards; wash them clean, and cast them in a good pot, and cast therein fresh beef broth or else (that) of mutton, and let it boil; and bind it with bread, and (add) pepper and saffron, maces, cloves, and a little verjuice and salt, and serve it forth in the manner as a broth.”

March 31, 2013

Welcome, Spring!

I have been on vacation this week, so my message is simple: Welcome, Spring! Glad to have you back.

The gate to our beautiful garden in Washington!

March 24, 2013

Field Trip

A few months ago, my husband Mike and I were traveling to Bend, Oregon, so I could give a reading at their beautiful public library. I was looking forward to seeing old friends, walking among Ponderosa pines, and going to Big R.

What—the local ranch supply store? Yep. No trip to Eastern Oregon is complete without it.

Where I grew up, in Minnesota, it was Mills Fleet Farm. Pretty similar, but with less ranching and more ice fishing. But either way—where else can you get work gloves of any description, fencing, live rabbits, and a meat bandsaw in one trip?

Man-sized safe? Check

Country-themed home décor? Of course

Pink camo jackets and country-themed lingerie? Natch

Chainsaws and accessories? Even a video showing a lumberjack competition!

In an earlier post about raising rural children, I used a few photos from the toy section. The children’s weaponry is all practically minded—hunting rifles and six-shooters. No flamethrowers or grenade-launchers. There is a bit more diversity in the real-gun section, but it’s still mostly oriented toward hunting. I would say the “adult” gun section, but country kids typically learn to shoot a gun before they’re ten …

The horse section is also spectacular. Bridles and ropes of every color. Mineral licks. Y mucho mas.

Toys for pastured horses

Bling is the thing for today’s horsewoman

If you want a crash-course in rural life, walk the aisles of one of these stores. You might even pick up some new garden boots, like I did.

No, not these!

March 17, 2013

Spring Planting

Spring! Depending on where you live, March might be time to plant tomatoes and cantaloupes (Southern states) or to cry into your seed catalogs as yet another snowstorm rolls through (Northern states). It’s by no means balmy in the Pacific Northwest, but nice enough to plant heartier things like brassicas and greens. And so I did.

As many of you know, my husband and I are currently in what I like to call “exile”—in a rental home in the city, trying to regroup for our next strike into the country. There are no vegetable garden beds on this property, so I am making do by sneaking in a few things along the flowered fence line. My motivation when picking things to plant is: What can I grow in not-perfect conditions that is expensive to buy in the store? Lettuce, dill, arugula (rocket), parsley and basil.

Parsley seeds need to soak for 24 hours; dill doesn’t transplant well so it will go straight into the ground. The rest go in pots.

Soaking parsley seeds in wet paper towels

You do not need to buy fancy seed-starter kits to get some plants going. Whatever you use just needs to be sturdy and to drain. I have seen people twist newspaper into little cups but have never tried it for fear that, once they’re wet, they will fall apart. (Plus, where does one get newspaper anymore? Ha.) Instead, I took a few empty yogurt and sour cream containers and punched holes in the bottom with a box-cutter—et voilá!

Cutting drain-holes

If possible, use starter mix; to save money I just bought regular planting soil. The reason for starter mix is it’s sifted to keep big chunks of vermiculite and organic matter out. A pea-sized hunk of bark wouldn’t bother a grown plant but it could stop completely the development of a tender seedling. So I go through and pick out the biggest chunks.

Clearing growth-hazards

Getting starts moisture is tricky; you can’t just dump a stream of water on them or you’ll uncover the seeds or knock the seedlings over. The best is to use a spray bottle (preferably a bottle that has held drinking water). Lacking a spray bottle, I held my fingers over a glass and forced the water to drip out slowly. Until the seedlings have roots there is no need to water the entire pot of soil; just the top inch is fine.

Some of you experienced gardeners may be saying: Basil? In March? Indeed, basil is a very tender plant that doesn’t take kindly to anything under 65 degrees. Never fear; I’m going to keep those pots inside—probably for three months!

Before ….

After!

March 10, 2013

“Bones” Video

As some of you know, my husband Mike Midlo is a storyteller disguised as a musician. His latest project, MidLo, received a grant from Portland’s Regional Arts & Culture Council, was released on March 5. As he did with his previous recording, Pancake Breakfast, Mike asked me to make a video for one of the songs. I made a stop-motion animation short for PB’s “Powerhouse Road” and assumed I would do the same for this video.

But, one afternoon in late September last year, he and I were driving home from a reading I did in Ashland, Oregon. Cruising up I-5, I gazed out the passenger window, enjoying how our shadow bounced along the side of the road. Suddenly, I realized I was watching a short film. The only camera I had was in my phone, so I decided to go for it.

The video is unadulterated—it runs straight through. The timing is uncanny in places. Enjoy my small contribution to Mike’s beautiful lament of our move away from the country, “Bones.”

March 3, 2013

Seed Catalogs A-Go-Go

They start showing up right after the solstice. Taunting me with full-color photos of prize tomatoes; fantastic dahlias; and firm, bulbous garlic heads. I’m talking about seed catalogs—every gardener’s weakness.

There are dozens of seed companies in the United States. Some focus on vegetables, some specialize in flower bulbs, some offer bare-root trees and bushes. Some just grow mushrooms, some just garlic! Below is as comprehensive list as I could muster.

I tend to buy from the companies that have their test gardens in my same region and growing zone. That way, if something works well in their garden it should also work well in mine! I usually order from Territorial Seed Company, and when I was in the Gorge I also liked Irish Eyes, based in Ellensburg, Washington—their climate was closer to mine than temperate Roseburg, Oregon.

The internet is full of videos that show you how to plant starts, space your plants out, and anything else having to do with gardening. There are also a number of garden-planning software packages appearing. I rely on gardening to keep me away from my computer, so I will never use anything but a pencil and sheet of graph paper to plan my garden beds. But some people find it helpful to be reminded when to plant what and so on. And having a computerized record does make it easier to track plantings and yields from year to year.

I would be remiss to talk about gardening without putting in a plug for saving seeds. You can use them the following year, or trade some with a friend for seeds you don’t have. This only works with “heirloom” varieties, i.e. plants that aren’t hybrids. Hybrids are crosses of two different types of plant to emphasize one or more traits over others (big fruits; sturdy stalks, etc.). They are great, but the seeds their fruits produce will not grow another hybrid plant. So, you have to keep buying more seeds.

Some large corporations have taken this marketing basis one step further and try to prosecute farmers who save their seed from a “trademarked” crop, or even who are affected by cross-pollination they don’t want! This mostly affects commodity farmers of corn, soybeans and rapeseed (canola), not food farmers.

Those interested in heirloom seed-saving and -trading should check out the Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa, Native Seeds/SEARCH in Arizona, Conserving Arkansas’ Agricultural Heritage, Organic Seed Alliance in Washington, International Seed Saving Institute in Arizona, Hudson Valley Seed Library in New York, and the National Gardening Association.

Many nurseries and gardening companies sell tools and resources as well as seeds—if you don’t see Get Your Pitchfork On! in your favorite catalog or store, please ask them to carry it.

Garden Seed Companies by State

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

Food Bank of North Central Arkansas

California

Peaceful Valley Farm & Garden Supply

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Florida Backyard Vegetable Gardener

Georgia

Hawai`i

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Earl May Nursery & Garden Center

Kansas

Kentucky

Sustainable Mountain Agriculture Center

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Missouri

Montana

New Hampshire

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

South Carolina

South Carolina Crop Improvement Assoc.

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

Washington

Backyard Heirloom Seeds & Herbs

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Here’s a few more, for mushrooms:

Back to the Roots, California

Gourmet Mushroom Products, California

Mushroom Adventures, California

Southeast Mushroom, Florida

Fungi Perfecti, Washington

And for garlic:

Garlic World, California

Charlie’s Gourmet Garlic, Ohio

Hood River Garlic, Oregon

Green Mountain Garlic, Vermont

Mushroom kits and garlic bulbs are offered by many of the seed companies as well. If you have others to recommend, please share them in the comments section. Happy Gardening!