Kristy Athens's Blog, page 3

September 7, 2014

Windfalls

Remember last week, when I was waxing poetic about the night sky? And I mentioned hearing crickets, and sprinklers, and Pendleton eating windfall apples? Well.

That night Pendleton, who has been housetrained for months, snuck down to the basement and laid an enormous, foul pile of heinous gastric gore on the floor. Mike gagged when he cleaned it up in the morning (lucky for me, I was asleep and oblivious). What could have caused this horrific display?

We have some gnarled old apple trees in our backyard. They could use a good pruning, but we don’t have a ladder and anyway, they aren’t mine and not everyone appreciates a “good pruning.” I didn’t bother to cull the fruits this spring, and now we have dozens of small apples falling out of the trees every time the wind blows. Pendleton’s been foreman of the clean-up crew.

At your service, ma’am

But the dogs are not the only ones who like free apples. The owner of the house we’re renting, last fall, told us that he kept the gate open so the deer could come in and browse. Otherwise, they all go to the wasps.

So, the morning in question, once I woke up and said, “Geez, it kind of smells like poop in here,” and Mike said, “You think?” before he went to take a shower, I walked out into the yard to collect the windfalls into a bucket, so Pendleton couldn’t reach them.

While I was out there, a doe walked up to the fence, as if to claim her autumn meal. The dogs went crazy. I calmed them, but the deer stayed put. Opening the gate is something of a formality, as any deer can jump a four-foot fence without even thinking about it. But she was, rightfully, afraid of the dogs and stayed put outside the fence.

I wanted to scare the doe off, so I threw what I had in my hand at her. As soon as I did, I realized it was a bad idea. The apple fell short, and then rolled a foot or two toward the doe. She didn’t jump or even move, just considered it, and then took a step toward the apple and gently picked it up, staring at us while she ate it. That was not the message I was hoping to send.

I left the dogs in the yard and scared the doe off. She’ll be back; this is where those nice people throw apples for you to eat!

Mike’s and my yard-maintenance routine has included picking up poo-piles and refilling holes that have been dug. For the next few weeks it will also include regularly collecting windfalls, depriving deer, dog, and wasp.

August 31, 2014

Stargazing

I was a bit disappointed to learn, my first summer back in a place without light pollution, that August’s Perseid meteor shower was going to be washed out by a full moon. The other night, I received a consolation prize.

I had finished my homework and was about to go to bed, when I realized it was pitch black outside. And relatively warm. I poured myself a nightcap, put on a sweatshirt, turned off the lights in the house, and carefully made my way down the steps to the backyard with Pendleton the dog.

It took a while for my vision to adjust. I closed my eyes for a minute to coax my pupils to dilate wide enough to take in the pinpoints. At first I saw only a few, then a few more, then ten times more, then twenty times more. After fifteen minutes or so, the Milky Way was fully visible, stretching across the sky toward Ruby Peak.

It’s all about waiting for the stars to come to you. I even caught a few shooting stars, perhaps remnants of the Perseids. I had to stand in a place that my vision wasn’t blocked overhead by the apple trees in our yard. What I should have done was walk out into the field, but I didn’t want Pendleton to rustle up any deer that were undoubtedly bedded down out there.

Mike and I were recently in Portland, visiting friends. Our friends’ kid was showing Mike her new bedroom furniture, and he pointed out that, from her bed, she could look out the window at the stars. She gave him a blank look. He remembered that you can only see a few stars in the city; not anything to impress a nine-year-old.

Standing in my yard, I was reminded of getting up at 4 in the morning every night last winter to let the puppies outside. In January, I regularly heard the Great horned owls conversing. Now, I could hear cows yelling, sprinklers whooshing, grasshoppers singing, and Pendleton munching on windfall apples.

I wished I could bring my friends’ kid out to our yard, so she would understand what Mike was talking about.

Photo from http://www.universetoday.com

August 24, 2014

Join Me in Conversation About Food

Oregon Humanities is one of the nation’s most innovative humanities councils, welcoming discussion rather than lectures. It’s a pleasure and an honor to have been accepted into their Conversation Project roster. My new program is called “Good Food, Bad Food: Agriculture, Ethics, and Personal Choice.” I hope you’ll join me in the conversation!

A slide from my PowerPoint conversation-starter! I found this receipt in the field by my house. It was dropped by someone who works there–a person who helps grow food who is on food stamps

How can you do that? The process is a little chicken-and-egg at first—an organization must contact me directly (kristy @ kristyathens.com) to talk about potential dates, and then apply to Oregon Humanities. However, if it doesn’t work out with them, or if the event is a fundraiser, for a private group, or some other qualifier that makes OH unable to sponsor it, they encourage CP leaders to make private arrangements. So you people in Hawai`i, please feel free to fly me out! January is open.

You can hear a little more about my topic in this video.

And view the entire catalogue here.

We’ll talk about the power of food in our personal and cultural mythologies, and how that correlates with our purchases. But exactly what we talk about will be up to you! I hope your library or other civic organization will invite me to visit! I’m looking forward to it.

August 17, 2014

Honey, I Canned the Peaches

Whenever I engage in domesticities such as canning, I refer to my bible, The Encyclopedia of Country Living. As I’ve noted in this blog, most recently when I canned apricots, I love its author, Carla Emery. And sometimes, love means you can tell someone to go jump in a lake.

I’m not someone who particularly enjoys process. So, just like e.e. cummings talked about the joy of “having written,” when I talk about the joy of canning peaches I am talking about the joy of having canned peaches. The act itself involves anxiety, minor burns, and swearing. I work really hard not to cut myself.

I put in an order with a local farmer for peaches a month or so ago, and they were finally ready on Thursday. I picked up my lug, and yesterday loaded my dishwasher with jars and set everything up: vat of boiling water, cutting board, steam canner. I consulted The Encyclopedia of Country Living, which had Carla’s instructions as well as my notes from past years about how many jars I’d used.

Canning prep

Carla wrote: “If you’re slow you can drop the fruit into water containing 2 T. each salt and vinegar per gallon water to prevent darkening. But I just work fast.” I filled another vat with water.

I was careful to buy freestone peaches so I wouldn’t have to deal with the stones sticking into the fruit. However, the peaches were just slightly underripe. Unlike Carla, who was a full-time back-to-the-land homemaker and could can her peaches at the exact right time, I have a schedule, and that schedule allowed me to can on Saturday. Not Wednesday, when the peaches would have been ready. By next week, they’d be too far gone. Now or never.

The result was that only a few of them separated the way they were supposed to. Mostly, I had to cut around the stone, which had stuck in one of the two halves, and then dig it out with a spoon. Even though I doused the peaches in boiling water, the skins only sort-of peeled off. Mostly I had to peel them with a paring knife. This was fussy.

“I just work fast,” Carla said. Go jump in a lake, Carla.

It was a good thing I had prepared the vinegar-salt water.

But, as with any problem, if you keep working at it you’ll eventually lick it. And I did. And my February-self will thank me!

See, that wasn’t so bad! Now, go ice those burns

August 10, 2014

Go to Farm School

Back in the day, a person learned how to farm by osmosis: they’d been doing chores since they could walk. But then mid-20th-century agriculture policies caused farmers to hit hard times; many of them actually encouraged their children to pursue other careers. The ones who stayed took up industrial farming. A couple generations later, young adults are renewing their interest in small farms but have no personal background to lean on. Most university-level ag programs are geared toward the children of industrial farms. Who is passing on the knowledge of family-sized farming?

Ten years ago, almost no one was. But things have changed—quickly. Oregon State University has launched a Small Farms program. Rogue Farm Corps, a farming internship program, is expanding from southern Oregon into Portland and Bend. Friends of Family Farmers has a Next Generation campaign. All of them, and others, are working to replenish the supply of farmers that is aging out of the industry.

Last September, on a whim, I went to an all-day “Small Farm School” workshop. It is run by the OSU program on the Clackamas Community College campus. There were a number of courses to choose from. Since I already know how to garden, I chose “On-Farm Veterinary Care,” “Honey Bee Biology and Beekeeping Basics,” and “Invasive and Perennial Weeds.” You can see this year’s options and register on their website. Here are some pictures!

We learned about giving vaccinations

We learned about hoof care

We learned about pasture (this stick shows how tall your grass should be)

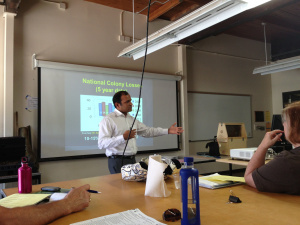

We learned about bees and colony collapse disorder

We learned about noxious weeds and how to combat them (I should have paid more attention when he talked about cheatgrass)

I had a great time and learned a lot. If you’re considering a career—or even a hobby—in farming, I recommend this workshop as a fairly inexpensive way to see how you like it!

August 3, 2014

New Icon, Same Game: “MyPlate” and Industry Interference

I’m taking summer courses—crazy, I know—because they were too good to pass up. I just finished a great class called “Food Policy and Law,” and here is one of my papers for it. I have a question for you: Both my husband and I distinctly remember getting a worksheet with the food pyramid in elementary school, i.e. the late 1970s. But according to my research this is impossible, as it didn’t get published until the 1990s. Does anyone else remember the food pyramid from earlier than that?

United States dietary policy is communicated via a publication entitled “Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” which is updated every five years (most recently in 2010). The purpose of the document is: “to be used in developing educational materials and aiding policymakers in designing and carrying out nutrition-related programs, including Federal nutrition assistance and education programs. The Dietary Guidelines also serve as the basis for nutrition messages and consumer materials developed by nutrition educators and health professionals for the general public and specific audiences, such as children” (USDA and U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2010, p. i).

This explanation is rather practical, compared with the loftier purpose stated in the introduction of the report itself: “The ultimate goal of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans is to improve the health of our Nation’s current and future generations by facilitating and promoting healthy eating and physical activity choices so that these behaviors become the norm among all individuals” (ibid., p. 1). This goal engages the culture of the United States, as well as its eating habits.

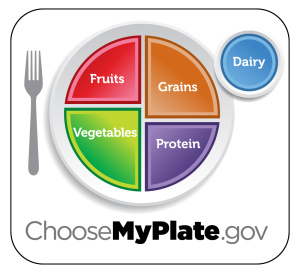

To make the guidelines more palatable to the general public, the USDA has issued a number of graphic pamphlets over the years. Their titles illustrate the culture of the time, such as “Food for Fitness” in the mid-1900s, when cars and household machines made leisure time (and, therefore, a sedentary lifestyle) a possibility for the middle class for the first time, and the “Hassle-Free Daily Food Guide” in 1979, when women began entering the workforce while still being expected to run the household (USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, 2011). Starting in 1992 the department made the illustration more cartoon-like, ostensibly in the service of their above-noted goal of appealing to children: first a pyramid and now a brightly colored plate.

Food for Fitness guide

MyPlate

The Food Pyramid, its fin de siècle tart-up MyPyramid, and most recent MyPlate schemes have many things in common, but some important differences. None of them reveals an invisible major player in how their guidelines were created: agriculture lobby organizations.

Effectiveness

The USDA Food and Nutrition Services is successful at the first goal stated above (developing educational materials and aiding policymakers), partly because their programs, such as The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and National School Lunch Program (NSLP) are required to base their guidelines and practices on the federal dietary guidelines. WIC is the most prescriptive of the programs, indicating exactly what the shopper may purchase. NSLP provides a participating school reimbursement for meals served, rather than supplying ingredients, with the exception of “bonus” foods, which are agricultural surpluses (USDA, 2013). SNAP is the least prescriptive, with individual recipients using a charge-card-type device with the cashier of a grocery store. While a few purchases are forbidden (tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, non-food items), the recipient has freedom of choice over brand, size, etc. (Fitzgerald et al., 2012).

The government’s effectiveness regarding its second, “ultimate” goal (to improve the health of our Nation’s current and future generations) is abysmal. The Trust for America’s Health reports that adult obesity rates have doubled since 1980, from 15 to 30 percent, while childhood obesity rates have more than tripled (n.d.). In an interview on the Public Broadcasting Service program Frontline, Dr. Walter Willet noted the disastrous effect of the country’s well-meaning nutritionists encouraging people in the 1970s and ‘80s to abandon butter (saturated fat) for margarine and shortening (hydrogenated or “trans” fat), causing heart disease and other health problems.

“[The Food Pyramid] is really not compatible with good scientific evidence, and it was really out of date from the day it was printed in 1991, because we knew, and we’ve known for 30 or 40 years that the type of fat is very important. That was totally neglected (emphasis mine)” (Willett, 2004).

Additionally, the federal government has lagged in considering culturally appropriate foods and non-carnivorous diets, and providing its information in languages other than English and Spanish (though some states have translated the materials, depending on the needs of their population). An organization called Oldways has attempted to fill this gap with its Mediterranean, Asian, Latin American, African Heritage, and vegetarian/vegan pyramids (n.d.).

Harvard University’s School of Public Health has refuted the value of the new MyPlate design roundly, criticizing it for not mentioning healthy unsaturated fats (e.g. olive or canola oil), for not condemning openly sugary drinks including fruit juice, and for supporting dairy products and refined grains (2011). MyPlate has absolved itself of any real responsibility on its website: “MyPlate is designed to remind Americans to eat healthfully; it is not intended to change consumer behavior alone (emphasis in original)” (USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, 2013).

Effects on Consumer Demand

In a general and surface-level way, Americans care about eating healthy food, or at least thinking about it. What matters, however, is when the fork hits the plate: Actual food choices are more relevant than intentions. What Americans understand about nutrition can affect their choices.

In this way, the inaccuracies of the Food Pyramid, and now MyPlate, can be devastating to the average consumer. People who think French fries are healthy because potatoes are listed as a vegetable, or that white dinner rolls are an appropriate grains serving, must know to look elsewhere to find better information (Green, n.d.).

There are a few possible reasons for the failure of the national nutrition standards to have resulted in worse, not better, health of the general populace. The main two are the success of marketing efforts for unhealthy food and beverage choices, and the flaws built into the Food Pyramid/MyPlate paradigm itself. The former is simply the result of a free market and consumer free will, which often results in unhealthful choices. The latter can be attributed to industry interference.

What is missing from the seemingly innocuous, even noble, goals of the USDA and HHS is the behind-the-scenes influence of agribusiness. This influence has affected what is in the dietary guidelines, and in the illustrated version of the guidelines, at least since Sen. George McGovern endeavored in 1977 to update the nation’s nutrition guidelines in light of new scientific findings—which recommended reductions in salt, meat, and sugar—and was soundly crushed by the American National Cattlemen’s Association, International Sugar Research Foundation, Salt Institute, United Egg Producers and numerous state egg councils, and National Live Stock and Meat Board, ultimately resulting in the complete corruption of the guidelines and the transfer of their purview from the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs to what is now the USDA (Greger, 2013).

Because government-funded food-supplement programs like SNAP and WIC are significant sources of funds ($78 billion in 2011 and $11.6 billion in 2012, respectively), agricultural lobbies work hard to keep their food items recommended. The most recent fight is over white (russet) potatoes. WIC does not provide potatoes, and the potato lobby is trying to change that. Not because they are concerned about the health of America’s low-income mothers, critics say, but because of the money they are missing out on (WIC is a $600 million program) and because of the public perception that potatoes must be “bad” if they’re not included (Nestle, 2014; Rampell, 2014).

Meanwhile, people who keep more rigorous habits than what MyPlate recommends rely on studies and reports from entities other than the federal government for their nutrition information, and tend to shop at farmers’ markets, natural food stores, and other farm-to-table outlets. The efforts of supporters of non-industrial, organically grown food have made some inroads with the federal government, but the results have been minimal. For example, the WIC Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program received $16.5 million in funding in 2011, which amounts to approximately 3 percent of the total WIC program (USDA, 2012). Of the $71.8 billion redeemed in SNAP benefits from 2010 to 2011, only $11.7 million was redeemed at farmers’ markets (Roper, 2012). Farm-to-school programs are gaining popularity but have a long way to go before they put a dent in the NSLP; hospitals and prisons are even more marginalized. Some restaurants voluntarily specialize in locally grown ingredients, but these are mid- to high-scale establishments.

While personal choice will always create a place for unhealthy foods and beverages, the federal government should at least provide accurate, sensible information about the components of a healthy diet. Until its dietary guidelines are separated from the USDA, which is essentially the chamber of commerce for U.S. agriculture, and overseen by nutritional scientists with no financial connection to the outcome of their findings, the United States will continue down its path of preventable diet-related obesity and disease.

Reference List

FitzGerald, K., Holcombe, E., Dahl, M., and Schwabisch, J. (2012, April). The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved from http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/04-19-SNAP.pdf

Food Pyramid Fight. (2004, Oct. 15). Government Executive, 36/18.

Green, L. (n.d.) Food Pyramid history. Retrieved from http://iml.jou.ufl.edu/projects/fall02/greene/history.htm

Greger, M. (2013, Apr. 12) The McGovern Report [Video]. Nutritionfacts.org. Retrieved from http://nutritionfacts.org/video/the-mcgovern-report/

Harvard School of Public Health. (2011, Dec.). Healthy Eating Plate dishes out sound diet. Harvard Heart Letter, Harvard Health Publications.

Nestle, M. (2014, Jan. 27). The fight over white potatoes in WIC. Food Politics. Retrieved from http://www.foodpolitics.com/2014/01/the-fight-over-white-potatoes-in-wic/

Oldways: Health Through Heritage. (n.d.) Why pyramids are important. Retrieved July 5, 2014, from http://oldwayspt.org/resources/heritage-pyramids/why-pyramids-are-important

Rampell, C. (2014, May 8). Big Potato lobbies to be part of WIC food assistance program. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/catherine-rampell-big-potato-lobbies-to-be-part-of-wic-food-assistance-program/2014/05/08/ed3251c6-d6c5-11e3-95d3-3bcd77cd4e11_story.html

Roper, N. (2012, January 18). SNAP redemptions at farmers markets exceed $11 million in 2011. Retrieved from http://farmersmarketcoalition.org/snap-redemptions-at- farmers-markets-exceed-11m-in-2011#sthash.csQXZcqT.dpuf

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. (2012, April). WIC Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WIC-FMNP-Fact-Sheet.pdf

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (2013, Sept.). National School Lunch Program. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/NSLPFactSheet.pdf

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture and U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. (2010, December). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 7th edition. Retrieved from http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/PolicyDoc/PolicyDoc.pdf

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. (2011, June). A brief history of USDA food guides. Retrieved from http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/downloads/myplate/abriefhistoryofusdafoodguides.pdf

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. (2013, Dec. 11). MyPlate. Retrieved from http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/myplate.htm.

Walter Willet, M.D. (2004, Apr. 4). Frontline [Web page interview]. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/diet/interviews/willett.html

July 27, 2014

Cheatgrass Sonsabitches

I apologize for the strong language. Once you’ve read my tale, you will understand.

This spring, Mike and I went out with our workgloves and pulled up or cut every plant we could find on our property with beautiful pink/purple flowers. We had learned that it was the source of the round, flat seeds our dogs are constantly plagued with—what are called “stick-tights” around here. They get in the dog’s fur, where dozens of hairs twist around them. Some get so twisted in you have to cut them out. They’re a pain! We were proud of ourselves for eradicating next season’s crop by killing the plants before they went to seed.

Bye-bye, stick-tights!

Meanwhile, all around us was another plant, one we weren’t familiar with. Just a simple little grass plant. We paid it no mind. That was a mistake.

Last Tuesday, both dogs started shaking their heads. Pendleton looked particularly miserable, constantly holding his head to the side. They’ve been swimming in the irrigation ditch to beat the heat, and we figured P must have gotten some water in his ear. I learned from my cousin’s partner that dogs with floppy ears are more prone to ear infections (their dog Quixote got one), so I thought maybe this was the issue.

Mike took P in to our veterinarian, Dr. Zwanziger at Red Barn Veterinary. He got out the otoscope and declared, “Cheatgrass!”

Cheatgrass?

Cheatgrass

It turns out that this little devil is going to make our lives a hundred times less fun than stick-tights ever could. Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) is an invasive weed whose seedheads are covered in hairs that stick them into a coat of fur, say, for transport to another area. Fine. The problem is that they don’t know when to quit, and can drive themselves to the base of the coat of fur, through the skin, and through muscle tissue, lungs, or even through the nose to the brain. Or down the ear canal and through an eardrum.

Pendleton was lucky; the cheatgrass was on his eardrum but hadn’t penetrated it. Dr. Zwanziger plucked it off, squirted some antibiotic ointment in there, and P was good to go. Pendleton’s sense of relief was palpable.

That evening, I was working on homework and Mike was talking to his mom on the phone. Suddenly, Cap’n started screaming. I ran into the living room, where she was cowering with her head tilted to the side. She was obviously in pain. Damn it.

I called Red Barn on their emergency line, and brought Cap’n in. She, too, had cheatgrass on both eardrums.

Mike and I were thereafter more diligent, checking their ears after every walk. On Thursday, both dogs were shaking their heads again. Not wanting to have to pay for another after-hours emergency visit, which is considerably more expensive, we scheduled an appointment for them on Friday.

Sure enough, both had more cheatgrass in their ears.

We asked Dr. Zwanziger for ideas of how to keep their ears closed. He offered up some bandaging that might work. It would work … but the dogs were so obsessed with removing it I thought they were going to run themselves into trees.

GET IT OFF!!

We checked their ears at regular intervals.

Monday, Cap’n was shaking her head again. This time, the cheatgrass had penetrated her eardrum. It should heal, Dr. Zwanziger said, but it might compromise her hearing. (And birds everywhere rejoiced …)

The cheerful Dr. Zwanziger

How would you like that on your eardrum?

We tried bandanas. They slid off their heads.

We tried cotton balls. They shook them out, and Pendleton promptly ate one.

If any of you, dear readers, have ideas about how to eradicate a stand of cheatgrass, or how to keep it out of a dog’s ears, please share them! These are active, young dogs that need more exercise than leash-walks and hanging out in the fenced yard can provide. There are no pristine green lawn-parks out here. As much as I want to support my vet, we can’t go there once (or twice, or thrice) a week …

July 20, 2014

Surprise Imnaha Apricots

As I’ve chronicled in previous posts, I have been struggling to get my kitchen groove back ever since we had to sell our land in the Columbia River Gorge. I never been much of a cook, but I had developed skills in baking and canning while on our land. When it went, so did my desire to carry on in the kitchen. Until I have my own house and garden, I imagine this will continue—I’m not heartbroken anymore, just waiting to settle in again.

However, a couple of weeks ago my colleague Sara (who has a great blog about her grass-fed beef operation) brought in to the office a box of apricots. I could feel my canning fingers get twitchy. I got home with those beautiful fruits and easily located our old country-living bible by Carla Emery on the bookshelf. It felt good to crack it open again. I had notes in the margin about canning peaches, so even though I’ve never canned apricots I had an idea of what lay before me.

Imnaha beauties!

You “can” always count on Carla

I hauled the canning equipment from the basement and tried to estimate how many jars I would need. I put them and the lids (which I still had from making jam last year, happily) in the dishwasher to get them going, and started washing and cutting apricots. I didn’t bother to peel them, like I would have done with peaches.

I prefer to pack fruit with water rather than simple syrup (sugar). I’ve found, at least with peaches, that the water turns into a delicious “liquor” that is as much a treat as the fruit itself.

Ready to can

Ready for February!

I wax poetic in Get Your Pitchfork On! about the joy of opening a jar of peaches in the winter. This February, we will have vibrant orange apricots, grown in the nearby Imnaha River Valley and picked by a friend, to brighten a cold winter’s day.

July 13, 2014

“Evil” in Corporate America

Dear Friends: I am taking summer-term classes and, once again, am behind on everything! So I’m, once again, taking the easy way out and posting an excerpt from a paper I wrote during winter term.

I have been a viewer of public television my entire life: I was raised on Sesame Street’s first broadcasts and have watched through the decades. I remember about ten or fifteen years ago hearing about some nefarious practice of the company Archer Daniels Midland, or ADM. That evil company!

“Wait a minute,” I thought. “The ADM that advertises on PBS?”

This was one of my first awakenings to the problematic nature of corporate sponsorship. How could PBS accept money from ADM and—more importantly—run “underwriting announcements” that tout ADM’s products and practices? Doesn’t PBS’s running that announcement (whether it should be called a commercial is the subject of another essay) imply their support of ADM? I suddenly found my lifelong trust in PBS disintegrating a bit.

Since then, I’ve witnessed many instances of corporate trespasses against humanity, animal rights, and ecology that are tempered by impressive public relations efforts to the contrary. Monsanto’s “Golden Rice” campaign. Ethanol. “Pork: The Other White Meat.”

My personal hesitation about genetically modified organisms (GMOs) has less to do about their potential health hazards and more to do with the business practices of the corporations that are developing them. If those companies want to develop GMO seeds, for example, and then let farmers buy them and then save them, resell them, or whatever they want; fine. But the idea of one, or even a handful of corporations, owning the world’s supply of seeds—the building block of life itself—well, that seems problematic. And it seems to be exactly what Monsanto and its ilk are up to. They have not shown themselves worthy of trust by mercilessly intimidating and chasing down small farmers who try to save their seed, and releasing teams of lawyers to sue them over patent infractions.

Photographer: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images

It all comes down to how one looks at the purpose of commerce. Do businesses exist to generate profit for an individual or group? Or do they exist to provide a means for people—all people—to live comfortably? My answer would be that the current American mindset is the former, and we need to move toward making it the latter.

However, I agree with Will Allen, executive director of Growing Power, that it’s in no one’s best interest to exclude America’s largest corporations from the conversation of creating an equitable food system. While it may seem counterintuitive to work with entities that ultimately have created the inequitable system we have, acting as though they are The Enemy simply guarantees the failure of grassroots equity efforts. It’s not a matter of righteousness, it’s a matter of scale.

Companies like ADM and Wal-Mart aren’t evil; they are simply wildly successful at the game of capitalism. So long as our society holds up capitalism as its model of success, there are going to continue to be ADMs and Wal-Marts. Refusing to work with such companies, including to refuse a monetary donation if offered one, will not eliminate them. It will simply starve an already cash-strapped effort.

This isn’t to say that any entity should accept money from a corporation like Wal-Mart that has any kind of strings attached. As Andrew Fisher pointed out during the FSS560 webinar on January 6, 2014, his organization refused a donation from Chipotle that required implicit endorsement on their part. But once his organization had refused it, Chipotle came back with an unrestricted donation, which they accepted. So long as a donation is a donation, and not a bribe or exchange for services (which keeps PBS on the hook as far as I’m concerned), and as long as the beneficiary doesn’t change its mission or operations in order to ameliorate the donor or attempt to attract other similar donations, I feel such donations should be welcomed as a step toward dialogue with members of the system that needs to be changed in order to achieve food justice.

Compromise is the key. There is no one effort that is going to change things overnight, and no one route. And, while we’re at it, no one vision of success. I’m generally not a process-oriented person, but I recognize that, in this case, process is the goal.

I appreciated Robert Egger’s encouragement of business leaders to embrace the “charity begins at home” notion by paying their employees living wages—very perceptive considering the efforts in 2013 by low-wage workers to demonstrate and make their plight known. Corporations have figured out how to game the system by paying their employees poverty wages, knowing they can make up the difference using taxpayer dollars via the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, housing subsidies, Women Infants and Children, and other federal entitlement programs. This, in my view, is cheating. Profit comes after paying overhead, and dodging overhead is bad business.

But, again, the corporate world considers this creative and successful accounting maneuvers. They are right. Ethically their actions are wrong; financially they are brilliant. Again, they’re not “evil,” just successful capitalists.

In order to change the actions of corporate America, we have to change the discourse of success in corporate America. The term “good corporate citizen” exists; we just have to make it mean something, and make consumers value that so they can pressure corporations to value that. It’s not profit that is the Enemy of the People; it’s the daisies that get trampled on the side of the road to profit.

July 6, 2014

Food Libeling

I got a check in the mail the other day. $8.57.

A year ago, a case was decided against PepsiCo for misrepresenting “all-natural” Naked Juice, which actually had a few synthetic ingredients in it, including (according to this website) “Archer Daniels Midland’s Fibersol-2 (‘a soluble corn fiber that acts as a low-calorie bulking agent’), fructooligosaccharides (an alternative sweetener), other artificial ingredients, such as calcium pantothenate (synthetically produced from formaldehyde), and genetically-modified soy.”

I honestly don’t remember how I learned of this class-action lawsuit, but I had indeed downed a few bottles of Naked Juice between Sept. 27, 2007, and Aug. 19, 2013, most of them at airports when I was on tour to promote Get Your Pitchfork On!, because it was one of the few remotely healthy items available. So, I filled out a claimant form.

This lawsuit—and its $9 million settlement (of which $3.12 million may go to the attorneys)—is chump change for PepsiCo, which denies wrongdoing and blames the lack of a federal definition of “natural” for the misunderstanding. But it’s indicative of the “food fight” that’s ramping up in the United States over who makes our food and what’s in it. Labeling efforts in New England, California, Washington and now, it appears, Oregon to identify genetically modified organisms in processed food are only the beginning. While I, personally, am less concerned about the health effects of GMOs and more concerned with the business practices of their parent companies (a big statement, I know), I do applaud this movement to know what’s in one’s food. It’s an old fight (think The Jungle by Upton Sinclair) and an important one.