Martin Pond's Blog, page 6

January 20, 2016

Not definite yet, just at the idea stage, but...

...if I curated a collection of short fiction, would you submit?

Let's be clear from the outset, it wouldn't make you money. And I'd be editing the collection, so submission is no guarantee of inclusion. But it would be published, at least as an ebook on Amazon and, possibly, also as a physical paperback with an ISBN that could be ordered/purchased anywhere.

Not totally committed to the idea yet, but if I put out the call for original short fiction, could you answer? Would you answer?

January 18, 2016

Whoop-de-doo, tarantula town

So, hooray for me, I finally finished the first draft of my novel-length work. Note how I still can't call it my novel. It's a manuscript, until it's published, and it just happens to be novel length (just - only 78k words). But anyway, whatever you want to call it, the first draft is finally finished. This ought to be cause for some celebration. After all, I've been working on the damn thing, off and on (increasingly off, decreasingly on) since June 2010. And don't get me wrong, I did celebrate a little, in my own way. I didn't punch the air, or crack open a bottle of anything, but I did have a quiet moment and a wry smile. Success! And yes, I am fully aware of how much work there still is to do, with editing and rewrites, filling logic and plot holes, all that good stuff. But success all the same.

So why the ironic post title? And why the "sad man" image, above? (Both explained by watching this.) It's this. My fictional (anti-)hero and I, well, we've been hanging out together, on paper and in my head, for five and a half years. I know him better than I know most of my work colleagues. He feels like a friend, albeit a messed-up friend with a whole host of problems. And since there won't be a sequel, that's it - that's his story told.

I won't be so crass as to say I'm in mourning, but I do feel some small sense of loss. I'm not writing the novel(-length work) any more. The fun part is over, and that huge emotional and intellectual investment, paid out over years, is suddenly gone. And I'm feeling it. Anyone else have the same problem?

I guess the obvious way to fill the void is to start on the next project but I can't, not whole-heartedly, until all the edits and re-writes of this one are done. In the meantime ... is there a "seven stages of grief for writers" out there, somewhere?

January 15, 2016

Learn from the greats ...

... or, since I am editing and have nothing new or finished to blog about, let me instead direct you to a recent(ish) article from The Guardian entitled Ten things I learned about writing from Stephen King. To me, "thing" seven is the crunch.

... or, since I am editing and have nothing new or finished to blog about, let me instead direct you to a recent(ish) article from The Guardian entitled Ten things I learned about writing from Stephen King. To me, "thing" seven is the crunch.

Still here? Go on, scat!

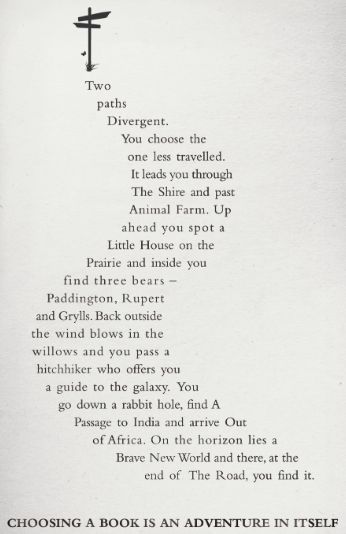

December 22, 2015

Christmas gift idea? Book tokens!

When I was a kid, one of the greatest presents you could get was a book token. Okay, it might not look much, a little slip of paper (then) in a scratty envelope - not much to unwrap there, or play with straight away. But the possibilities... and the choice... and the anticipation...

And the hours I spent in the narrow (even for a kid) aisles of the sadly now-defunct Albion Bookshop, with a book token carefully folded in my pocket... golden moments, those.

I was reminded of all this when I saw an ad for National Book Tokens this morning, which centred around this:

I count around fifteen references there, how about you?

Anyway, while you're thinking about that, if you're stuck for last-minute Christmas gift ideas, especially for kids, don't just buy them chocolate or an iTunes giftcard. Buy them a book token. They might not all thank you for it - you risk your own moment of "I hate Uncle Jamie" - but you're giving the gift of possibilities, choice, anticipation... and books. What could be finer?

November 3, 2015

Amazon goes full circle...

...and opens an actual, physical bookshop.

The BBC have the full story. Amazon has its own spin too.

November 2, 2015

Theory and practice of editing

The inestimable Andrew Collins's recent rediscovery of his own article on The New Yorker brought this to my attention, this being Wolcott Gibbs's "Theory and Practice" from 1937. It's aimed at journalists generally, and those working on TNY in particular, but there's something here for us all, and especially me as I'm currently editing the first draft of a novel-length manuscript. On that basis, I reproduce it here for you now, verbatim.

The Theory And Practive Of Editing by Wolcott Gibbs

THE AVERAGE CONTRIBUTOR TO THIS MAGAZINE IS SEMI-LITERATE; that is, he is ornate to no purpose, rull of senseless and elegant variations, and can be relied on to use three sentences where a word would do. It is impossible to lay down any exact and complete formula for bringing order out of this underbrush, but there are a few general rules.

Writers always use too damn many adverbs. On one page, recently, I found eleven modifying the verb "said": "He said morosely, violently, eloquently," and so on. Editorial theory should probably be that a writer who can't make his context indicate the way his character is talking ought to be in another line of work. Anyway, it is impossible for a character to go through all these emotional states one after the other. Lon Chancy might be able to do it, but he is dead.Word "said" is O.K. Efforts to avoid repetition by inserting "grunted," "snorted," etc., are waste motion, and offend the pure in heart.Our writers are full of cliches, just as old barns are full of bats. There is obviously no rule about this, except that anything that you suspect of being a cliche undoubtedly is one, and had better be removed.Funny names belong to the past, or to whatever is left of Judge magazine. Any character called Mrs. Middlebottom or Joe Zilch should be summarily changed to something else. This goes for animals, towns, the names of imaginary books and many other things.Our employer, Mr. Ross, has a prejudice against having too many sentences begin with "and" or "but." He claims that they are conjunctions and should not be used purely for literary effect. Or at least only very judiciously.See our Mr.Weekes on the use of such words as "little," "vague," "confused," "faintly," "all mixed up," etc., etc. The point is that the average New Yorker writer, unfortunately influenced by Mr. Thurber, has come to believe that the ideal New Yorker piece is about a vague, little man helplessly confused by a menacing and complicated civilization. Whenever this note is not the whole point of the piece (and it far too often is) it should be regarded with suspicion.The repetition of exposition in quotes went out with the Stanley Steamer:Marion gave me a pain in the neck.This turns up more often than you'd expect.Another of Mr. Ross's theories is that a reader picking up a magazine called The New Yorker automatically supposes that any story in it takes place in New York. If it doesn't, if it's about Columbus, Ohio, the lead should say so. "When George Adams was sixteen, he began to worry about the girls he saw every day on the streets of Columbus" or something of the kind. More graceful preferably.Also, since our contributions are signed at the end, the author's sex should be established at once if there is any reasonable doubt. It is distressing to read a piece all the way through under the impression that the "I" in it is a man and then find a woman's signature at the end. Also, of course, the other way round.To quote Mr. Ross again, "Nobody gives a damn about a writer or his problems except another writer." Pieces about authors, reporters poets, etc., are to be discouraged in principle. Whenever possible the protagonist should be arbitrarily transplanted to another line of business. When the reference is incidental and unnecessary, it should come out.This magazine is on the whole liberal about expletives. The only test I know of is whether or not they are really essential to the author's effect. "Son of a bitch," "bastard" and many others can be used whenever it is the editor's judgment that that is the only possible remark under the circumstances. When they are gratuitous, when the writer is just trying to sound tough to no especial purpose, they come out.In the transcription of dialect, don't let the boys and girls misspell words just for a fake Bowery effect. There is no point, for instance, in "trubble," or "sed."Mr.Weekes said the other night, in a moment of desperation, that he didn't believe he could stand any more triple adjectives. "A tall, florid and overbearing man called Jaeckel." Sometimes they're necessary, but when every noun has three adjectives connected with it, Mr.Weekes suffers and quite rightly. I suffer myself very seriously from writers who divide quotes for some kind of ladies club rhythm. "I am going," he said, "downtown" is a horror, and unless a quote is pretty long I think it ought to stay on one side of the verb. Anyway, it ought to be divided logically, where there would be pause or something in the sentence.Mr.Weekes has got a long list of banned words beginning with "gadget." Ask him. It's not actually a ban, there being circumstances when they're necessary, but good words to avoid.I would be delighted to go over the list of writers, explaining the peculiarities of each as they have appeared to me in more than ten years of exasperation on both sides.Editing on manuscript should be done with a black pencil, decisively. I almost forgot indirection, which probably maddens Mr. Ross more than anything else in the world. He objects, that is, to important objects, or places or people, being dragged into things in a secretive and underhanded manner. If, for instance, a Profile has never told where a man lives, Ross protests against a sentence saying "His Vermont house is full of valuable paintings." Should say "He had a house in Vermont and it is full, etc." Rather weird point, but it will come up from time to time.Drunkenness and adultery present problems. As far as I can tell, writers must not be allowed to imply that they admire either of these things, or have enjoyed them personally, although they are legitimate enough when pointing a moral or adorning a sufficiently grim story. They are nothing to be light-hearted about. " The New Yorker cannot endorse adultery." Harold Ross vs. Sally Benson. Don't bother about this one. In the end it is a matter between Mr. Ross and his God. Homosexuality, on the other hand, is definitely out as humor, and dubious, in any case.The more "as a matter of facts," "howevers," "for instances," etc., you can cut out, the nearer you are to the Kingdom of Heaven.It has always seemed irritating to me when a story is written in the first person, but the narrator hasn't got the same name as the author. For instance, a story beginning: "George," my father said to me one morning; and signed at the end Horace Mclntyre always baffles me. However, as far as I know this point has never been ruled upon officially, and should just be queried.Editors are really the people who should put initial letters and white spaces in copy to indicate breaks in thought or action. Because of overwork or inertia or something, this has been done largely by the proof room, which has a tendency to put them in for purposes of makeup rather than sense. It should revert to the editors.For some reason our writers (especially Mr. Leonard Q. Ross) have a tendency to distrust even moderately long quotes and break them up arbitrarily and on the whole idiotically with editorial interpolations. "Mr. Kaplan felt that he and the cosmos were coterminus" or some such will frequently appear in the middle of a conversation for no other reason than that the author is afraid the reader's mind is wandering. Sometimes this is necessary, most often it isn't.Writers also have an affection for the tricky or vaguely cosmic last line. "Suddenly Mr. Holtzman felt tired" has appeared on far too many pieces in the last ten years. It is always a good idea to consider whether the last sentence of a piece is legitimate and necessary, or whether it is just an author showing off.On the whole, we are hostile to puns.How many of these changes can be made in copy depends, of course, to a large extent on the writer being edited. By going over the list, I can give a general idea of how much nonsense each artist will stand for.Among other things, The New Yorker is often accused of a patronizing attitude. Our authors are especially fond of referring to all foreigners as "little" and writing about them, as Mr. Maxwell says, as if they were mantel ornaments. It is very important to keep the amused and Godlike tone out of pieces.It has been one of Mr. Ross's long struggles to raise the tone of our contributors' surroundings, at least on paper. References to the gay Bohemian life in Greenwich Village and other low surroundings should be cut whenever possible. Nor should writers be permitted to boast about having their telephones cut off, or not being able to pay their bills, or getting their meals at the delicatessen, or any of the things which strike many writers as quaint and lovable.Some of our writers are inclined to be a little arrogant about their knowledge of the French language. Probably best to put them back into English if there is a common English equivalent.So far as possible make the pieces grammatical, but if you don't the copy room will, which is a comfort. Fowler's English Usage is our reference book. But don't be precious about it.Try to preserve an author's style if he is an author and has a style. Try to make dialogue sound like talk, not writing.

"You give me a pain in the neck, Marion," I said.

Footnote: if you're looking for a good, modern and free style guide for the English language, you could do a lot worse than The Guardian's.

October 30, 2015

Fight Club 4 Kids

You'll have seen this already, because you're savvy and hipsterish, neither adjectives that could be applied to me. But it bears repetition, featuring, as it does, a terrific author ripping the proverbial out of one of my favourite books. Of course, he's allowed to - he wrote it.

Here you go. You're welcome.

September 29, 2015

Notes from Write On Kew

I went to the inaugural Write On Kew literary festival at Kew Gardens over the weekend. Not the whole thing - that would have become very expensive over the course of the four day programme - but I did spend all day there on Saturday. In each of the sessions I attended, I scribbled notes of things that particularly struck me. Words of wisdom, or interest, or curiosity, from writers who are more successful in their genres than I seem to be, and my observations about them. Providing I can decipher my lap-leaning scrawl, I'll reproduce the notes for you, here.

Melvyn Bragg - discussing Now Is The Time, his novel inspired by the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

MB is a small man with enviable hair. He has leather elbows on a tweed coat ["Is that the best you can do?" - Ed] and speaks very fast - ideas tumble out.MB draws repeated parallels between the social and political circumstances that led to the uprising of 1381 to those prevailing in the UK now.MB: "[The peasants' revolt was the] ... seeding of a radical line in this country".MB is absolutely embedded in the history of this period, demonstrating a rich knowledge with detailed anecdotes. He studied this period at school and also read history at university.MB: "If you're doing a job you like - really, really like - it gives you energy. If you're doing a job you don't like, it takes your energy away." (When asked how he manages to write so much, fiction and non-fiction, whilst maintaining his broadcasting work)Pat Barker - discussing Noonday, the concluding part of her Second World War trilogy.

PB: "We all write our own histories."PB: "Talk to the two people in a divorce - Russia and America have nothing on it." (On illustrating the above)PB: "A writer never wants the full story."PB: "Your genetic inheritance is waiting for you in the mirror." (On becoming more like her parents with age)PB: "[It's very important for] ... any child who's going to be a novelist to be a detective."PB: "There's no such thing as a normal family, only families we don't know very well."A woman (Helen Duncan) was tried for witchcraft in the UK in 1944.PB: "We need empathy, and we need tolerance as we have never needed it before."PB: "History tends towards generalisations. Only fiction can be particular."Whilst enthusing about keeping diaries, PB recommended The Assassin's Cloak, an anthology of diarists.PB: "When she's writing at speed, she does capture something that is lost in her more ornate prose." (On Virginia Woolf, despite the tense)PB: "It's very difficult to write virtue without attaching a flaw."Turning to crime - Sophie Hannah, Stuart Prebble and Paula Hawkins in conversation with Mark Lawson.

PH: "[I am] ... fascinated by the terrible things people do to each other."PH: "People can behave in extreme ways we can't being to imagine." (On plausibility)SH: "People are weirder than we can possibly imagine, and when we put them under pressure they become even weirder." (On plausibility)ML has a nervous twitch in his left eye, but it stops when he is speaking.SH: "I try to have a plot hook and a theme in every book."SH: "Readers really dislike certainty."SP: "I used to go to the keyboard to find out what happened next." (On plotting/planning)SH: "People undervalue plot, so don't use their imagination's ingenuity."SH: "Psychological thrillers should have non-transferable motives." (On distinguishing psychological thrillers from thrillers)SH: "Any constraint is also an opportunity."PH: "On Amazon and GoodReads, 'I don't like the main character' is a one-star thing." (On the merits of (un-)likeable protagonists)ML: "The Great Gatsby is essentially the tale of a fraud narrated by a crashing bore. It's also the perfect novel and I re-read it every year." (On the merits of (un-)likeable protagonists)Simon Armitage - discussing Walking Away, his account of reading poetry for his supper on a long, coastal walk.

The hall is packed, busiest session I've been to all day.SA has a relaxed, measured reading voice - unhurried.The host/compère, Christina (surname?) seems a bit doe-eyed around SA.SA mentions the Lyke Walk, a 40-mile walk to be completed in 24 hours. Successful walkers are awarded a badge in the shape of a coffin.SA: "As a writer, I have a tendency to get a bit solipsistic, a bit introspective, and so a bit negative."SA: "The more distracted I am, the more I seem to notice." (On noticing surroundings)SA: "It becomes a very intimate thing, walking, especially if there's just two of you. You end up telling each other things. One of the reasons you share so much when you're walking is that you don't have eye contact, so become less guarded."SA: "Cornwall is a bit like a Christmas stocking - the biggest nuts fall to the bottom."Christina: "Graham Greene talked about 'the chip of ice in the heart'." (On honest detachment)SA: "Poetry is not a front-line art form. It takes itself more seriously than other people take it ... [but] ... there is still a market for it."SA: "Poetry has huge potential that goes much wider than the printed page."SA: "I still find poetry bewildering on occasion. I know it's an odd thing because I've seen the look on people's faces when I tell them that's what I do."SA: "I think we still have, in this country, this person called 'the Constant Reader' ... less and less in other English-speaking countries ... [where] ...poetry has imploded into the universities."SA: "In Ezra Pound language, I transpose the Underworld into Poundland." (On his poem, Poundland)SA: "There is only really one piece of advice - to read! I'd take it further - you need to find people you can imitate. People you're so jealous of, you have to write your own versions. One other bit - don't! I don't need some young smart alec snapping at my heels." (When asked by a teenage girl in the audience for one piece of advice for a young writer)SA: "I always talk about Ted Hughes in answer to that question ... through Hughes, Larkin, Thomas [indistinguishable], Sylvia Plath ... American poetry of the Fifties and Sixties ... poetry that arrives in a voice, speaking to you in some way. American poets of that time had more conversational language. If someone had lobbed me in the deep end with Chaucer, I probably would have drowned ... my favourite poets at the moment are all dead, and the longer they've been dead the better." (On being asked, from the audience, which poets had inspired him)What else can I tell you? Kew is a terrific setting, not least because you can take in the gardens between sessions. The Princess Of Wales Conservatory was fascinating, as was watching the largest grebe I've ever seen wrestling with an eel for a good ten minutes in the little lake by the Palm House. The grebe won, in the end.

Anyway, Write On Kew will doubtless happen again next year. I'd go if I were you - I think you'd like it.

September 8, 2015

It takes one to know one (or, Stephen King questions the virtues of being productive)

Given that King himself is no slouch in this regard, it's a safe bet he knows what he's talking about. Anyway, you're here because you're interested in writing, probably, so maybe you'll find this of interest too. Here's the inevitable link:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/31/opinion/stephen-king-can-a-novelist-be-too-productive.html

June 3, 2015

How to summarise an 85,000-word novel in 300 words

I'm fortunate, I suppose, to have never really been touched by the death of someone close. My dog dying, in my early teens, is the closest I've come so far. And I've had other things to mourn - a friendship, principally, rent asunder by the sudden imposition of 3,750 miles in-between us. But death? No, I've been lucky, so far.

I have been thinking about it a lot though, recently. A writing friend has just suffered the loss of a sibling. That's terrible enough. That they are comparatively only magnifies the sense of what is lost.

I am not quite so young... but the message here is clear. It's obvious, isn't it - I could go at any time. So, as Tim Robbins says, as Andy Dufresne in The Shawshank Redemption, get busy living or get busy dying. Time to crack on, get the novel finished. Try and do something with it. Avoid, if at all possible, the thought of waking up one day and wishing I'd done more with my writing.

To that end, I entered the Bridport Novel Award at the weekend. It was a bit eleventh hour, and involved some drastic, high-speed synopsis editing. My previous draft synopsis was 653 words long; for Bridport, it has to be 300 or less...

As you might imagine, that was quite hard. In fact, I didn't think I was going to make it. I tried a complete reimagining of what the synopsis might be, but ended up just writing a back-cover blurb instead. And then it hit me. Part of the reason summarising in 300 words proved so hard was that I was trying to tell the whole story, in short form but sequentially, as it happens in the novel version, and it just wasn't possible. So instead, I started to group together events from the novel that are thematically similar, though thousands of words apart. Then, I had one short paragraph about my protagonist's loss of the only people he has left to depend on rather than one paragraph about his mother's dementia and another about the erosion of a friendship.

And it worked. The net result was a synopsis that doesn't tell the story exactly as the story happens, but still summarises all the main points of the story. I think that's all you can realistically hope to achieve in 300 words. Mine was 299, since you ask. And yes, I had to lose some detail - gone were all references to place (Cambridge) and time (the long, hot summer of 2009), but they were small word count savings. The big ones came from the structural Damascene moment described above. You probably know this stuff already but I thought I'd share it anyway, just in case.

Realistic Bridport outcome? I might get some feedback. Dream outcome? Well, the longlist would do me. I can dream, can't I?

Get busy living or get busy dying? As Red observes in the film's coda, that's goddamn right.