Chris Fabry's Blog, page 11

May 5, 2012

Furry Hope

Every now and then God gives a glimpse of hope where you least expect it. I asked my daughter, Kristen, to take a picture of Tebow on the back of the couch because I wanted to tie it to the song, “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay.” Tebow singing, “Sittin’ on the Back of the Couch” seemed like a great tweet to me.

But what happened was serendipitous to say the least. Check out the picture of our pup.

Here’s the rest of the story. In our home in Colorado we had a U-shaped leather couch and Pippen would crawl on the back of one side and Frodo would be on the other. It was sort of a balancing act they did with our lives. We didn’t teach them to sleep on the back of the couch, they just loved it up there.

Here’s the rest of the story. In our home in Colorado we had a U-shaped leather couch and Pippen would crawl on the back of one side and Frodo would be on the other. It was sort of a balancing act they did with our lives. We didn’t teach them to sleep on the back of the couch, they just loved it up there.So when Tebow began, a couple of weeks ago, to do the same thing, it brought the memories back. Love and loss and everything in between.Hence, the picture. It says it all. In the midst of sorrow and pain, there is joy. In your desert are flowers. When things seem darkest, there’s hope.

I don't always see it, but sometimes the truth breaks through with fur on.

Published on May 05, 2012 16:59

May 4, 2012

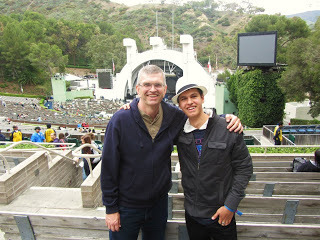

Pictures from California Trip

Published on May 04, 2012 10:31

May 1, 2012

The Devil and The Writer

Usually I listen to the accusations and don’t respond. Eventually he goes away. But there was something different about this day.

“You’re a failure,” he said.

“You always say that.”

“Because it’s true. You are a flat-out failure at life and everything you do. Especially the writing.”

A pause. Maybe he’s right. “I’m trying,” I said.

“You’re a child playing with words you don’t understand.”

“I’m a child who’s been forgiven.”

“Ach, Cliché! Who cares if you’re forgiven, you’re still a failure. You’re a loser. You’ve worked how long to get to this point? Decades? You still have nothing to show for it.”

Thinking. Waiting for a comeback. I utter something but my heart is not in it. “It’s taken me this long to realize I have everything I need.”

The Devil laughed. “Right. And that’s why you look so intently at the best-seller lists. And when you walk in a bookstore and can’t find a single thing you’ve written, you get depressed.”

Silence.

“If I were you, I’d curse God.” He plopped a stack of bills in front of me. “You call this blessing?”

It was an unusually large stack. And there were more in the kitchen.

“Face it. God doesn’t care about you. You pray, you plead. He’s not listening.”

A clock ticked somewhere in the room. It was the only sound, other than my heart.

“You’re trying to praise this God of yours with an inconsequential life. With your inconsequential talent.”

He tapped the screen. “This is garbage. Hackneyed, putrid fluff.”

He drew close enough that I smelled his sulphurous breath. “You sit at your desk filled with unpaid bills and pretend you’re reaching people’s hearts. And your ego brings you back to the page because you think that one day someone will notice your greatness.”

Perhaps he’s right. I do have expectations of being noticed. That someone will actually read my words. “I would be lying if I didn’t admit I feel inadequate at times.”

“Inadequate? You’re not even in the ballpark. You must have talent to be inadequate.”

I wanted to find some scripture, some sentence like, “Man does not live by bread alone,” but I couldn’t. I was confused again, the way he always confuses.

“Admit it, you’re a failure. Let me pull up the bestseller list. What a surprise. I don’t see your name.”

Stammering now, shaking, I said, “My success is not measured in numbers. My success is measured by how faithful I—”

“Faithful?” he said, bellowing. “You fail him every day with your attitude and your thoughts and your words and the way you treat your family and feed your ego by sitting here pretending all of this is important.”

I pondered his words. Some truth skittered through my mind. Measured and even I said, “First of all, you don’t know my thoughts unless I express them. Second, you’re right, I make many mistakes. But every time you bring up failure, he brings forgiveness.”

“Oh, please. Give up. You are never going to amount to anything.”

Something flashed inside, like a warning light, a signal from somewhere deep. Real truth I need not simply understand but claim.

“If I’m never going to amount to anything, why are you here?”

He paused. His eyes darted.

“Why wouldn’t you be content to let me flail away if I’ll never amount to anything?”

“Because I hate failures.”

“Perhaps you’re projecting,” I said, wind picking up the sails. “You know, when you put on me the things—”

“I know what projecting is, you don’t have to explain.”

“You lost. You failed. In fact, you thought you had won, but at the cross—”

“Enough,” he screamed, and it was a long, reverberating shout of pain and anguish, as if I had tapped some primeval spring.

“I don’t value your opinion,” I said. Instead of lashing out, his voice flattened.

What if I offered you success?”

“Tempting, but that fruit is stale.”

“But I have power. You have no idea. A million dollar advance. A big house overlooking the ocean.”

“I don’t need the view. And I’m not selling my soul.”

“Really? Every man has his price. Name it. Anything you want. Anything at all.”

I looked at him squarely. You can always see fear in the eyes.

“You can’t buy what’s already been sold.”

“What?”

I shrugged. “I’m not my own. I’ve been bought for a high price. By God himself. You want me, you’ll have to dicker with the owner.”

He turned to walk away, muttering. “You’ll always be a failure.”

I almost felt sorry for him.

“You’re a failure,” he said.

“You always say that.”

“Because it’s true. You are a flat-out failure at life and everything you do. Especially the writing.”

A pause. Maybe he’s right. “I’m trying,” I said.

“You’re a child playing with words you don’t understand.”

“I’m a child who’s been forgiven.”

“Ach, Cliché! Who cares if you’re forgiven, you’re still a failure. You’re a loser. You’ve worked how long to get to this point? Decades? You still have nothing to show for it.”

Thinking. Waiting for a comeback. I utter something but my heart is not in it. “It’s taken me this long to realize I have everything I need.”

The Devil laughed. “Right. And that’s why you look so intently at the best-seller lists. And when you walk in a bookstore and can’t find a single thing you’ve written, you get depressed.”

Silence.

“If I were you, I’d curse God.” He plopped a stack of bills in front of me. “You call this blessing?”

It was an unusually large stack. And there were more in the kitchen.

“Face it. God doesn’t care about you. You pray, you plead. He’s not listening.”

A clock ticked somewhere in the room. It was the only sound, other than my heart.

“You’re trying to praise this God of yours with an inconsequential life. With your inconsequential talent.”

He tapped the screen. “This is garbage. Hackneyed, putrid fluff.”

He drew close enough that I smelled his sulphurous breath. “You sit at your desk filled with unpaid bills and pretend you’re reaching people’s hearts. And your ego brings you back to the page because you think that one day someone will notice your greatness.”

Perhaps he’s right. I do have expectations of being noticed. That someone will actually read my words. “I would be lying if I didn’t admit I feel inadequate at times.”

“Inadequate? You’re not even in the ballpark. You must have talent to be inadequate.”

I wanted to find some scripture, some sentence like, “Man does not live by bread alone,” but I couldn’t. I was confused again, the way he always confuses.

“Admit it, you’re a failure. Let me pull up the bestseller list. What a surprise. I don’t see your name.”

Stammering now, shaking, I said, “My success is not measured in numbers. My success is measured by how faithful I—”

“Faithful?” he said, bellowing. “You fail him every day with your attitude and your thoughts and your words and the way you treat your family and feed your ego by sitting here pretending all of this is important.”

I pondered his words. Some truth skittered through my mind. Measured and even I said, “First of all, you don’t know my thoughts unless I express them. Second, you’re right, I make many mistakes. But every time you bring up failure, he brings forgiveness.”

“Oh, please. Give up. You are never going to amount to anything.”

Something flashed inside, like a warning light, a signal from somewhere deep. Real truth I need not simply understand but claim.

“If I’m never going to amount to anything, why are you here?”

He paused. His eyes darted.

“Why wouldn’t you be content to let me flail away if I’ll never amount to anything?”

“Because I hate failures.”

“Perhaps you’re projecting,” I said, wind picking up the sails. “You know, when you put on me the things—”

“I know what projecting is, you don’t have to explain.”

“You lost. You failed. In fact, you thought you had won, but at the cross—”

“Enough,” he screamed, and it was a long, reverberating shout of pain and anguish, as if I had tapped some primeval spring.

“I don’t value your opinion,” I said. Instead of lashing out, his voice flattened.

What if I offered you success?”

“Tempting, but that fruit is stale.”

“But I have power. You have no idea. A million dollar advance. A big house overlooking the ocean.”

“I don’t need the view. And I’m not selling my soul.”

“Really? Every man has his price. Name it. Anything you want. Anything at all.”

I looked at him squarely. You can always see fear in the eyes.

“You can’t buy what’s already been sold.”

“What?”

I shrugged. “I’m not my own. I’ve been bought for a high price. By God himself. You want me, you’ll have to dicker with the owner.”

He turned to walk away, muttering. “You’ll always be a failure.”

I almost felt sorry for him.

Published on May 01, 2012 08:41

April 23, 2012

Not Getting Over It

The LDS Church has had a successful media campaign with their phrase, “…and I’m a Mormon.” Slick ads with real people talking about their faith. Yesterday at an evangelical church in California, Glenn Beck changed the slogan.

Let me first say, I like Glenn. I think he’s funny, well-read, a family man, and I’d want him as my neighbor if he moved to Arizona. I think he’s right about getting our country back to the Constitution. He was certainly right about buying gold a couple of years ago.

But when Glenn stood in a church yesterday and held up a Bible and said, “This is what we need to get back to,” and the 2,000 in the congregation applauded, something felt off.

Glenn’s Church thinks the Bible has been corrupted. Perhaps mistranslated is the better term. They say it can’t be trusted in certain places. That’s why you need other books. Their books.

Glenn said, with a wry smile, “I’m a Mormon. Get over it.”

There was some applause. Some scattered laughter.

There are two ways to interpret this statement:

Interpretation 1. “Look, I believe something different about God than you evangelical Christians. I don’t believe in the Trinity. My Church has other books, other testaments we add to the Bible. And there are many more differences theologically. But let’s not let our theological differences keep us from joining hands and working for the common good of our country.”

If this is what Glenn meant, I understand and agree. I have Mormon neighbors. One helped me with my irrigation line in our front yard over the weekend. Our kids play together. We can join hands and work together for the common good, no question.

Interpretation 2. “Look, I’m a Christian just like you. I believe in Jesus. He’s my Savior. I pray to him every day. He talks to me. God is leading us together. Get over my Mormonism.”

If Glenn meant this, I have a BIG problem. Because Glenn is not just talking about “common good,” he is talking about a “common Lord.”

Here’s why I’m leaning toward Interpretation 2:

Immediately following his statement, “I’m a Mormon. Get over it,” he said he believed in the same “God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” that Christians do. He also said to a room with 2,000 believers, “We are the team. We are the ones to prepare the way of the Lord.”

Really? Which Lord? Which coming? I’m confused.

After the Restoring Honor rally in 2010, Chuck Colson pondered some good questions on Breakpoint. He wondered what “gospel” was being spread at the Lincoln Memorial. “What ‘God’ are we supposed to turn back to?”

They were good questions then. It’s a good question now. This is a Chuck Colson moment. What “team” are we on that’s preparing the way of which “Lord?”

I’m not trying to be divisive. I love and respect the pastor who organized the Sunday event in California. I know he wants us to get our country on a good path. Perhaps he regrets this small part of what went on there yesterday.

But we stand at a crossroad bigger than the next election. We stand at a crossroad of truth and error. And the path we choose and the way we lead those who follow have eternal consequences.

Let me first say, I like Glenn. I think he’s funny, well-read, a family man, and I’d want him as my neighbor if he moved to Arizona. I think he’s right about getting our country back to the Constitution. He was certainly right about buying gold a couple of years ago.

But when Glenn stood in a church yesterday and held up a Bible and said, “This is what we need to get back to,” and the 2,000 in the congregation applauded, something felt off.

Glenn’s Church thinks the Bible has been corrupted. Perhaps mistranslated is the better term. They say it can’t be trusted in certain places. That’s why you need other books. Their books.

Glenn said, with a wry smile, “I’m a Mormon. Get over it.”

There was some applause. Some scattered laughter.

There are two ways to interpret this statement:

Interpretation 1. “Look, I believe something different about God than you evangelical Christians. I don’t believe in the Trinity. My Church has other books, other testaments we add to the Bible. And there are many more differences theologically. But let’s not let our theological differences keep us from joining hands and working for the common good of our country.”

If this is what Glenn meant, I understand and agree. I have Mormon neighbors. One helped me with my irrigation line in our front yard over the weekend. Our kids play together. We can join hands and work together for the common good, no question.

Interpretation 2. “Look, I’m a Christian just like you. I believe in Jesus. He’s my Savior. I pray to him every day. He talks to me. God is leading us together. Get over my Mormonism.”

If Glenn meant this, I have a BIG problem. Because Glenn is not just talking about “common good,” he is talking about a “common Lord.”

Here’s why I’m leaning toward Interpretation 2:

Immediately following his statement, “I’m a Mormon. Get over it,” he said he believed in the same “God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” that Christians do. He also said to a room with 2,000 believers, “We are the team. We are the ones to prepare the way of the Lord.”

Really? Which Lord? Which coming? I’m confused.

After the Restoring Honor rally in 2010, Chuck Colson pondered some good questions on Breakpoint. He wondered what “gospel” was being spread at the Lincoln Memorial. “What ‘God’ are we supposed to turn back to?”

They were good questions then. It’s a good question now. This is a Chuck Colson moment. What “team” are we on that’s preparing the way of which “Lord?”

I’m not trying to be divisive. I love and respect the pastor who organized the Sunday event in California. I know he wants us to get our country on a good path. Perhaps he regrets this small part of what went on there yesterday.

But we stand at a crossroad bigger than the next election. We stand at a crossroad of truth and error. And the path we choose and the way we lead those who follow have eternal consequences.

Published on April 23, 2012 07:01

April 17, 2012

Three Boys and a Horse

The two-lane country road that ran past our house was still unpaved and dusty as a an old saddle. Plumes would follow cars on hot summer days and the flies and heat were oppressive.

Mosquitoes searched the dry creek bed and settled for blood from the veins of West Virginia boys.

Sweat trickled down our dirty backs and faces. It was impossible not to have wet hair, and I suppose that’s what sent us out on our bikes that day. The wind felt good on your face as long as you pedaled hard.

“Car!” my brother yelled.

We would pull over as far as we could near a fenceline and wait, shielding our mouths and eyes from the floating grit.

That’s what a childhood in West Virginia tastes like. Dust between your teeth and chapped lips and the smell of wild lilacs that flower on hillsides. Mosquitoe bites that turn into scabs that are picked bloody. Panting dogs and nervous squirrels.

My memory of that day is hazy. It only came back to me recently as a quick, jittery image. A horse standing too close to the road. Blood and gore and barbed wire to the meat.

“Hey Dave!” My voice was squeaky. Girlish. My mother’s friends would call our home and I’d pick up the big, black, Bell telephone that weighed almost as much as I did and answer—and they always thought it was her.

“Kath-ern?” they would say, mispronouncing her name, Kathryn.

“Come on, catch up,” he yelled. Or I imagine he yelled. What does a brother who is eight years older say to a little fat kid with a squeaky voice?

We both think Bud Shirkey was with us that day, but we do not have independent verification of such. My brothers called him Elvis because he always sang some pop tune as he walked around the bend in the road and his voice echoed off the hills.

Whether Bud was there or not, and whether I was actually the one who spotted the horse we don’t recall. But there are facts we know. The horse had gotten hung up in the barbed wire fence and the metal had wrapped all the way around its leg. Struggling against it had wedged the barbs deeper into the meat and blood ran down and the flies had been notified that dinner was served.

“What are we going to do?”

There was no question we were going to do something. There was no question that coming upon the scene of such tragedy brought a compulsion to act.

But what do we do? The horse belonged to Vessie Sowards. Not the most genial of men in the county. He might have been a prince for all I knew, but he had a reputation to little kids of being stern. Mean. (Whether this was true is not the point. It is the perception of a man in a child’s eyes that counts in such times of distress.)

“We gotta cut the wire,” my brother said.

“Old Vessie’l be mad if you do that,” Bud said. If he was there.

“Stay here with the horse,” my brother said. “We’ll go get the wire cutters.”

And with that they were off, down the road, kicking up dust. Bud’s old bike clanging.

Bud didn’t have a bike. His family was too poor. Maybe he stayed with me. Maybe he wasn’t even there. It’s not important. When memories like this come, I want to get the detail. The time of year. Were there june bugs? Japanese beetles? Fireflies at night? But I can’t make it clear. The snapshots are fuzzy and the film in the camera jumps on the spindle of memory.

The horse looked scared and I tried to calm it with my voice. I must have done something like that. Me on my banana seat that barely contained me. In the summer I would slim down and burn the fat riding the roads and looking for beer bottles to set up and break with rocks at fifteen paces. But in the winter it was back inside to my mother’s fudge and pound cakes and there was always that temptress, Little Debbie, with the cute smile and the hat on her head and those oatmeal cream pies. Demon woman. I’ll carry her secret sins with me to the grave.

It always came down to food in the West Virginia hills. Hot dogs and battered shrimp and marshmallows and fried chicken and macaroni salad and potato salad and rolls and spitting watermelon seeds. I remember talking to my brothers once when their friends were over and saying, “I’ll bet one day they’ll invent a watermelon that doesn’t have any seeds.”

They all laughed. “How are you going to get a watermelon to grow if it doesn’t have seeds?” They hooted and rolled on the ground as if I did not understand male and female anatomy, which I didn't.

I knew early on that without vision a people perish.

Dave rode back to the scene with the wire cutters and hesitated. It was a big, towering workhorse. The animal nickered and swished his tail at the flies and looked like he could rear up and stomp all three of us. He put his head toward the wire and tried to get at it with his teeth, but he couldn’t.

Bud must have gone to Vessie’s house to tell him what happened. That’s how it went. Dave went for the wire cutters, Bud went to find Vessie, and I stayed with the horse. Yes, it's coming back now.

“We should wait,” I said.

Fear brings doubt and doubt and death are kissing cousins.

Dave, who would become a chemist and work with petroleum much later in life, must have known he had to cut the wire or the horse would do even greater damage to its leg. So he tentatively cut one side, mashing with both hands until the click. And the horse tried to move back and the blood streamed faster and Dave moved to the other side but the wire was being torn away by the retreating horse and everything whirred and swam in my vision...

Click.

He was free. Free as a bird to fly and kick up his heels in the pasture. But he stayed right there and looked at us. Me, the fat little kid who had noticed him in distress. Dave, the skinny, no brawn, all brains kid who had the gumption to get the wire cutters and the will to use them.

It was a surreal moment, suspended in time. Just the three of us looking at each other and the sun beating down and the flies and blood and sweat in the still, calm of summer.

I believe it was that day that I realized the power of noticing small things. We could have kept on riding but the horse had been too close to the road, and I had seen it. Maybe that’s what a writer does, the best thing he does, and all he does. Simply notice and call attention to things we pass. Plain things. Ordinary. Secretly wounded.

And then a car came. Or an old truck. Yes, it was probably a truck. Rusted out. Balding tires. I’m picturing a Chevy with the rounded hood. And Vessie Sowards got out and hurried to us in coveralls. Manure on his boots and hay down his shirt collar.

“I’m sorry I had to cut your fence, Mr. Sowards,” Dave said.

“No, no,” he said, inspecting the wounded horse. He took a moment, then dramatically turned to the three of us. “Why this horse could have died out here. Just bled out. Or he could have torn all the tendons in that leg if you’d have left him there.”

We looked at the horse and at Vessie but not at each other. There is a quiet humility among heroes. Inside we were beaming. On the outside it was…it was just men being men, doing their jobs, caring for creation and women-folk. Anyone worth his salt would have done the same thing.

And that’s where the picture fades and the film snaps and I am left with the faint smell of sweaty boys and a horse with wire sticking out of his leg.

As far as I know the horse made a full recovery. And Vessie praised us for getting involved, taking responsibility.

I mentioned this to my brother the other day and the memory was just as vivid for him. He said Vessie told us he was going to give us a reward for what we had done. As thanks for our heroic act, he gave an open-ended promise that something good would come our way.

It’s been 40 years and my brother is still checking his mailbox. There’s been no check, no deed to the farm, no firstborn foal.

All we have is the memory. Faded and jumpy and unclear in places. And somehow that feels like enough.

Mosquitoes searched the dry creek bed and settled for blood from the veins of West Virginia boys.

Sweat trickled down our dirty backs and faces. It was impossible not to have wet hair, and I suppose that’s what sent us out on our bikes that day. The wind felt good on your face as long as you pedaled hard.

“Car!” my brother yelled.

We would pull over as far as we could near a fenceline and wait, shielding our mouths and eyes from the floating grit.

That’s what a childhood in West Virginia tastes like. Dust between your teeth and chapped lips and the smell of wild lilacs that flower on hillsides. Mosquitoe bites that turn into scabs that are picked bloody. Panting dogs and nervous squirrels.

My memory of that day is hazy. It only came back to me recently as a quick, jittery image. A horse standing too close to the road. Blood and gore and barbed wire to the meat.

“Hey Dave!” My voice was squeaky. Girlish. My mother’s friends would call our home and I’d pick up the big, black, Bell telephone that weighed almost as much as I did and answer—and they always thought it was her.

“Kath-ern?” they would say, mispronouncing her name, Kathryn.

“Come on, catch up,” he yelled. Or I imagine he yelled. What does a brother who is eight years older say to a little fat kid with a squeaky voice?

We both think Bud Shirkey was with us that day, but we do not have independent verification of such. My brothers called him Elvis because he always sang some pop tune as he walked around the bend in the road and his voice echoed off the hills.

Whether Bud was there or not, and whether I was actually the one who spotted the horse we don’t recall. But there are facts we know. The horse had gotten hung up in the barbed wire fence and the metal had wrapped all the way around its leg. Struggling against it had wedged the barbs deeper into the meat and blood ran down and the flies had been notified that dinner was served.

“What are we going to do?”

There was no question we were going to do something. There was no question that coming upon the scene of such tragedy brought a compulsion to act.

But what do we do? The horse belonged to Vessie Sowards. Not the most genial of men in the county. He might have been a prince for all I knew, but he had a reputation to little kids of being stern. Mean. (Whether this was true is not the point. It is the perception of a man in a child’s eyes that counts in such times of distress.)

“We gotta cut the wire,” my brother said.

“Old Vessie’l be mad if you do that,” Bud said. If he was there.

“Stay here with the horse,” my brother said. “We’ll go get the wire cutters.”

And with that they were off, down the road, kicking up dust. Bud’s old bike clanging.

Bud didn’t have a bike. His family was too poor. Maybe he stayed with me. Maybe he wasn’t even there. It’s not important. When memories like this come, I want to get the detail. The time of year. Were there june bugs? Japanese beetles? Fireflies at night? But I can’t make it clear. The snapshots are fuzzy and the film in the camera jumps on the spindle of memory.

The horse looked scared and I tried to calm it with my voice. I must have done something like that. Me on my banana seat that barely contained me. In the summer I would slim down and burn the fat riding the roads and looking for beer bottles to set up and break with rocks at fifteen paces. But in the winter it was back inside to my mother’s fudge and pound cakes and there was always that temptress, Little Debbie, with the cute smile and the hat on her head and those oatmeal cream pies. Demon woman. I’ll carry her secret sins with me to the grave.

It always came down to food in the West Virginia hills. Hot dogs and battered shrimp and marshmallows and fried chicken and macaroni salad and potato salad and rolls and spitting watermelon seeds. I remember talking to my brothers once when their friends were over and saying, “I’ll bet one day they’ll invent a watermelon that doesn’t have any seeds.”

They all laughed. “How are you going to get a watermelon to grow if it doesn’t have seeds?” They hooted and rolled on the ground as if I did not understand male and female anatomy, which I didn't.

I knew early on that without vision a people perish.

Dave rode back to the scene with the wire cutters and hesitated. It was a big, towering workhorse. The animal nickered and swished his tail at the flies and looked like he could rear up and stomp all three of us. He put his head toward the wire and tried to get at it with his teeth, but he couldn’t.

Bud must have gone to Vessie’s house to tell him what happened. That’s how it went. Dave went for the wire cutters, Bud went to find Vessie, and I stayed with the horse. Yes, it's coming back now.

“We should wait,” I said.

Fear brings doubt and doubt and death are kissing cousins.

Dave, who would become a chemist and work with petroleum much later in life, must have known he had to cut the wire or the horse would do even greater damage to its leg. So he tentatively cut one side, mashing with both hands until the click. And the horse tried to move back and the blood streamed faster and Dave moved to the other side but the wire was being torn away by the retreating horse and everything whirred and swam in my vision...

Click.

He was free. Free as a bird to fly and kick up his heels in the pasture. But he stayed right there and looked at us. Me, the fat little kid who had noticed him in distress. Dave, the skinny, no brawn, all brains kid who had the gumption to get the wire cutters and the will to use them.

It was a surreal moment, suspended in time. Just the three of us looking at each other and the sun beating down and the flies and blood and sweat in the still, calm of summer.

I believe it was that day that I realized the power of noticing small things. We could have kept on riding but the horse had been too close to the road, and I had seen it. Maybe that’s what a writer does, the best thing he does, and all he does. Simply notice and call attention to things we pass. Plain things. Ordinary. Secretly wounded.

And then a car came. Or an old truck. Yes, it was probably a truck. Rusted out. Balding tires. I’m picturing a Chevy with the rounded hood. And Vessie Sowards got out and hurried to us in coveralls. Manure on his boots and hay down his shirt collar.

“I’m sorry I had to cut your fence, Mr. Sowards,” Dave said.

“No, no,” he said, inspecting the wounded horse. He took a moment, then dramatically turned to the three of us. “Why this horse could have died out here. Just bled out. Or he could have torn all the tendons in that leg if you’d have left him there.”

We looked at the horse and at Vessie but not at each other. There is a quiet humility among heroes. Inside we were beaming. On the outside it was…it was just men being men, doing their jobs, caring for creation and women-folk. Anyone worth his salt would have done the same thing.

And that’s where the picture fades and the film snaps and I am left with the faint smell of sweaty boys and a horse with wire sticking out of his leg.

As far as I know the horse made a full recovery. And Vessie praised us for getting involved, taking responsibility.

I mentioned this to my brother the other day and the memory was just as vivid for him. He said Vessie told us he was going to give us a reward for what we had done. As thanks for our heroic act, he gave an open-ended promise that something good would come our way.

It’s been 40 years and my brother is still checking his mailbox. There’s been no check, no deed to the farm, no firstborn foal.

All we have is the memory. Faded and jumpy and unclear in places. And somehow that feels like enough.

Published on April 17, 2012 23:02

April 10, 2012

Father-Daughter Haircut

I've never gotten a father-daughter haircut before, but that's what happened last night. Kristen and I went for new do's.

We pulled up to the salon at 7:15 and I darted through the door with my coupon in hand. That's right, not just a father-daughter haircut, but a discount father-daughter haircut.

"Sorry, we're full," the not-so-polite person at the front said.

We walked away, but I would not be deterred. We backtracked, drove down a couple of deserted streets, and came to the same salon at a different location.

No one inside waiting.

Yes!

I took my chair, Kristen took hers. She explained what she wanted and it sounded a little complicated for the stylist. It sounded complicated to me, the layering and bangs and all that hair talk.

"What are we going to do tonight?" my stylist said.

Of course this is stylist speak. WE aren't going to do anything, I am going to sit still and let you whack off as much hair as possible without cutting off my oversized ears. I've always been self-conscious about them. My brothers said if my plane ever went down people would fight to use them as flotation devices.

I told the young woman what to do and she asked no questions. What happened was the most vigorous and timely haircut in the history of haircuts. No chit-chat. No, "So, what do you do?" No, "How many children do you have?" It was a relief not to get the grill. I just sat and absorbed the cranial massage.

And then I noticed it. Right on the plastic bib or whatever you call that thing they hang around you there was a big clump of white hair. How did my father's hair get in my lap? No, not white, it was gray. Like an old dog. A big pile of gray hair. An old man's hair falling onto the floor and my arms and shoulders. How did that get here?

I remember when it was brown and wavy. There's a spot in the back where my dad had an awful time—the cow lick, he called it. But she didn't blink. She just ran that buzzer up and down, spraying gray hair like it was confetti during a Super Bowl celebration. Salt and pepper hair spewing forth in celebration of years of stress and anxiety.

She didn't hold the mirror up and ask me how I liked it, but that was okay because I didn't have my glasses and couldn't see a thing except the gray hair that was now in the floor. I thought I saw it move. Like it could crawl away.

Kristen's stylist, as I predicted, didn't understand the layering/bangs thing. But her hair did look much cuter, partly because she doesn't have my ears. And she doesn't have my father's hair either.

But she did have her father's coupon.

We pulled up to the salon at 7:15 and I darted through the door with my coupon in hand. That's right, not just a father-daughter haircut, but a discount father-daughter haircut.

"Sorry, we're full," the not-so-polite person at the front said.

We walked away, but I would not be deterred. We backtracked, drove down a couple of deserted streets, and came to the same salon at a different location.

No one inside waiting.

Yes!

I took my chair, Kristen took hers. She explained what she wanted and it sounded a little complicated for the stylist. It sounded complicated to me, the layering and bangs and all that hair talk.

"What are we going to do tonight?" my stylist said.

Of course this is stylist speak. WE aren't going to do anything, I am going to sit still and let you whack off as much hair as possible without cutting off my oversized ears. I've always been self-conscious about them. My brothers said if my plane ever went down people would fight to use them as flotation devices.

I told the young woman what to do and she asked no questions. What happened was the most vigorous and timely haircut in the history of haircuts. No chit-chat. No, "So, what do you do?" No, "How many children do you have?" It was a relief not to get the grill. I just sat and absorbed the cranial massage.

And then I noticed it. Right on the plastic bib or whatever you call that thing they hang around you there was a big clump of white hair. How did my father's hair get in my lap? No, not white, it was gray. Like an old dog. A big pile of gray hair. An old man's hair falling onto the floor and my arms and shoulders. How did that get here?

I remember when it was brown and wavy. There's a spot in the back where my dad had an awful time—the cow lick, he called it. But she didn't blink. She just ran that buzzer up and down, spraying gray hair like it was confetti during a Super Bowl celebration. Salt and pepper hair spewing forth in celebration of years of stress and anxiety.

She didn't hold the mirror up and ask me how I liked it, but that was okay because I didn't have my glasses and couldn't see a thing except the gray hair that was now in the floor. I thought I saw it move. Like it could crawl away.

Kristen's stylist, as I predicted, didn't understand the layering/bangs thing. But her hair did look much cuter, partly because she doesn't have my ears. And she doesn't have my father's hair either.

But she did have her father's coupon.

Published on April 10, 2012 20:34

April 6, 2012

Jesus Was Not Nice

I'm beginning to believe Jesus was not a nice person. Holy and nice are not synonymous. Holy means perfect, which I am not. And neither are you.

Was Jesus nice to people? Well, yes, but not always. He was kind to children. He was gentle and humble. But he was also a force to be reckoned with. Powerful men don't crucify nice people.

There must be something more to Jesus than "nice."

I guess that's what I've never understood. How could the Romans and Jewish leaders have killed someone so tame? So humble? So…bland?

I've seen Jesus as insipid. Following him has felt dull. As if the real action in life is somewhere else. Following someone else. And Jesus can wait till the weekend.

From his birth to his death to his resurrection, he was on a mission. No military leader, athlete, or political powerbroker ever had a mission like this. And the pressure he must have felt…

Satan is like a lion on the prowl, ready to devour. But he doesn't even compare with Jesus—for he is the Lion of Judah. And this Lion was out to destroy the chains of sin that bind you and me.

I'm glad Jesus was not simply a nice guy. Nice guys don't die for you. Nice guys don't satisfy the demands of a holy, righteous God. Nice guys don't embrace nails and sweat blood.

Passion. Love. Surrender. This is much more than nice.

Was Jesus nice to people? Well, yes, but not always. He was kind to children. He was gentle and humble. But he was also a force to be reckoned with. Powerful men don't crucify nice people.

There must be something more to Jesus than "nice."

I guess that's what I've never understood. How could the Romans and Jewish leaders have killed someone so tame? So humble? So…bland?

I've seen Jesus as insipid. Following him has felt dull. As if the real action in life is somewhere else. Following someone else. And Jesus can wait till the weekend.

From his birth to his death to his resurrection, he was on a mission. No military leader, athlete, or political powerbroker ever had a mission like this. And the pressure he must have felt…

Satan is like a lion on the prowl, ready to devour. But he doesn't even compare with Jesus—for he is the Lion of Judah. And this Lion was out to destroy the chains of sin that bind you and me.

I'm glad Jesus was not simply a nice guy. Nice guys don't die for you. Nice guys don't satisfy the demands of a holy, righteous God. Nice guys don't embrace nails and sweat blood.

Passion. Love. Surrender. This is much more than nice.

Published on April 06, 2012 13:33

March 10, 2012

The Rest of the Story About MFA

My experience with MFA, my favorite author, challenged me. It made me want to treat readers differently. It made me want to value them. Not that MFA didn't value me, he had no idea the connection I had and how much the moment I described earlier meant.

Fast forward a few years. I had the signed book I received from MFA as well as two others. These were treasures, in spite of the earlier experience.

Then the unthinkable happened. We left our house and all the possessions we had amassed in 25+ years of marriage. Clothes, furniture, computers, and yes, signed books. I won't go into the reason, but it was important for us to leave it all behind.

It made the top ten list of most difficult things to do in life. Turn and walk away. Don't go back. That's what we did, we turned and moved forward with life and left all of that behind.

Last year was my 50th birthday. My wife handed me a present with a smile saying she knew I would like it. I'm not easy to buy for. My love language is not gifts. So when I opened the present and saw a copy of MFA's book, it felt surreal, like something lost had been found. I hadn't dreamed of replacing it.

Then came the long story of an acquaintance who had heard of our story. She had another friend who lived near MFA. This courageous woman had an illness, but when she learned of the loss and how much I love MFA, she said, "I'll go over to his house."

Can you imagine showing up on the doorstep of an author and asking him to autograph a book for someone you don't even know?

Two books were in the package. The first was one of my favorite novels inscribed to my wife and me. The other was a more current nonfiction book about reading. Inside I read:

"To Chris,

Happy 50th Birthday. My best to you in your writing life. Go deeper. Always go deeper."

The hurts and disappointments of life are an invitation to go deeper. And to see the truth. And every now and then it comes together and makes sense.

That's a gift only the author of life can give.

Fast forward a few years. I had the signed book I received from MFA as well as two others. These were treasures, in spite of the earlier experience.

Then the unthinkable happened. We left our house and all the possessions we had amassed in 25+ years of marriage. Clothes, furniture, computers, and yes, signed books. I won't go into the reason, but it was important for us to leave it all behind.

It made the top ten list of most difficult things to do in life. Turn and walk away. Don't go back. That's what we did, we turned and moved forward with life and left all of that behind.

Last year was my 50th birthday. My wife handed me a present with a smile saying she knew I would like it. I'm not easy to buy for. My love language is not gifts. So when I opened the present and saw a copy of MFA's book, it felt surreal, like something lost had been found. I hadn't dreamed of replacing it.

Then came the long story of an acquaintance who had heard of our story. She had another friend who lived near MFA. This courageous woman had an illness, but when she learned of the loss and how much I love MFA, she said, "I'll go over to his house."

Can you imagine showing up on the doorstep of an author and asking him to autograph a book for someone you don't even know?

Two books were in the package. The first was one of my favorite novels inscribed to my wife and me. The other was a more current nonfiction book about reading. Inside I read:

"To Chris,

Happy 50th Birthday. My best to you in your writing life. Go deeper. Always go deeper."

The hurts and disappointments of life are an invitation to go deeper. And to see the truth. And every now and then it comes together and makes sense.

That's a gift only the author of life can give.

Published on March 10, 2012 13:13

February 28, 2012

Meeting My Favorite Author

I remember the excitement. Bone-thrilling anticipation. I was going to meet my favorite writer and listen to him speak and buy a signed copy of his new book. Even take a picture if they would allow it.

I drove an hour to a massive bookstore and wandered the stacks on several floors and looked at the pictures of the famous writers who had been there before and thought this was the most holy of places. This collection of talent and wit and literary acumen was unparalleled.

Chairs were set up throughout a room down a narrow hallway and there was a stack of books at the front and a lectern. I positioned myself about halfway back near a speaker. I didn't want to be first in line, I wanted to linger on every word, every story told, and wait for our meeting.

My favorite author is a raconteur, a storyteller, a fabulist. He spun a web of stories that night that lingered over the audience like a fog, shrouding us with elegance and beauty and pain. He told some stories about his childhood that made sense of his writing, that explained why he had chosen to put down his stories. It was wonderful and sad and triumphant.

Now you must understand that I had stalked this writer for years. I had gone to his home state and even vacationed near his home, thinking that I might catch a glimpse of him in his natural habitat. I caught no glimpse, but there was born inside an insatiable desire to one day shake his hand, look him in the eye, and tell him what his stories meant to me.

When the talk was over I got in line and waited, listening to the laughter and titters and stories around me. People whose lives had been enriched by this man. Former classmates of his. Friends from around the country. Cultured and refined people. I remained silent, inching forward as he took time with each person, even allowing photos to be snapped.

When it was my turn he asked my name and what I wanted signed. I told him. And then, fumbling over my words like a nervous schoolboy, I revealed as much as I could about what his writing had meant to me, how I had been moved.

He looked past me, toward the line. Perhaps there was someone there he knew. Perhaps he was hungry and wanted to go to dinner and was gauging how much longer he would need to sign. Or perhaps there was a beautiful woman behind me that caught his eye.

I can't remember what he said, exactly, but in that moment I sensed something I will never forget. It was a feeling that springs from the bottom of life's well and churns and bubbles up. Disappointment. A feeling that others behind me were more important. I was an obstruction. Another book to sign. Please move forward.

Let me hasten to say that if he had stood and embraced me and asked me to dinner afterward, it would have been a letdown. Nothing he could have done would have lived up to the affection in my heart. But this was…well, rejection at worst and indifference at best.

I didn't get my picture taken with him. Maybe I had lost the desire. I snapped one from my perch beyond the table, with him alone, red-faced, signing his name, smiling at the person behind me. It was a good picture. Wall-worthy, even.

Driving home I felt the inexpressible loss of a dream. Foolish to think this writer, this famous person, would in any way regard me. I had conjured up this grand connection between us, a literary umbilical chord. But there was no attachment from his side of the page.

"How was it?" my wife said when I returned.

"It was okay," I said. "He told some great stories."

I had the photo developed and decided to give him another chance. To give me another chance, really. The dream lives in the hearts of readers. Hope is hard to kill. You can put your foot on its neck but it will rise just about every time.

I put the photo in an envelope with a short note, asking him to sign it. I included a self-addressed, stamped envelope.

Perhaps it never reached him. Perhaps he tossed it away. It never returned.

There is more to this story, however. Much more.

I drove an hour to a massive bookstore and wandered the stacks on several floors and looked at the pictures of the famous writers who had been there before and thought this was the most holy of places. This collection of talent and wit and literary acumen was unparalleled.

Chairs were set up throughout a room down a narrow hallway and there was a stack of books at the front and a lectern. I positioned myself about halfway back near a speaker. I didn't want to be first in line, I wanted to linger on every word, every story told, and wait for our meeting.

My favorite author is a raconteur, a storyteller, a fabulist. He spun a web of stories that night that lingered over the audience like a fog, shrouding us with elegance and beauty and pain. He told some stories about his childhood that made sense of his writing, that explained why he had chosen to put down his stories. It was wonderful and sad and triumphant.

Now you must understand that I had stalked this writer for years. I had gone to his home state and even vacationed near his home, thinking that I might catch a glimpse of him in his natural habitat. I caught no glimpse, but there was born inside an insatiable desire to one day shake his hand, look him in the eye, and tell him what his stories meant to me.

When the talk was over I got in line and waited, listening to the laughter and titters and stories around me. People whose lives had been enriched by this man. Former classmates of his. Friends from around the country. Cultured and refined people. I remained silent, inching forward as he took time with each person, even allowing photos to be snapped.

When it was my turn he asked my name and what I wanted signed. I told him. And then, fumbling over my words like a nervous schoolboy, I revealed as much as I could about what his writing had meant to me, how I had been moved.

He looked past me, toward the line. Perhaps there was someone there he knew. Perhaps he was hungry and wanted to go to dinner and was gauging how much longer he would need to sign. Or perhaps there was a beautiful woman behind me that caught his eye.

I can't remember what he said, exactly, but in that moment I sensed something I will never forget. It was a feeling that springs from the bottom of life's well and churns and bubbles up. Disappointment. A feeling that others behind me were more important. I was an obstruction. Another book to sign. Please move forward.

Let me hasten to say that if he had stood and embraced me and asked me to dinner afterward, it would have been a letdown. Nothing he could have done would have lived up to the affection in my heart. But this was…well, rejection at worst and indifference at best.

I didn't get my picture taken with him. Maybe I had lost the desire. I snapped one from my perch beyond the table, with him alone, red-faced, signing his name, smiling at the person behind me. It was a good picture. Wall-worthy, even.

Driving home I felt the inexpressible loss of a dream. Foolish to think this writer, this famous person, would in any way regard me. I had conjured up this grand connection between us, a literary umbilical chord. But there was no attachment from his side of the page.

"How was it?" my wife said when I returned.

"It was okay," I said. "He told some great stories."

I had the photo developed and decided to give him another chance. To give me another chance, really. The dream lives in the hearts of readers. Hope is hard to kill. You can put your foot on its neck but it will rise just about every time.

I put the photo in an envelope with a short note, asking him to sign it. I included a self-addressed, stamped envelope.

Perhaps it never reached him. Perhaps he tossed it away. It never returned.

There is more to this story, however. Much more.

Published on February 28, 2012 06:07

February 21, 2012

True Words

The car in front of us was going the speed limit. My daughter had her earphones in. She glanced at the clock.

"Can you pass him?"

Deadpan. As if she had the power to move heaven and earth.

I glanced at her. Not too long. I might have swerved. I glanced back at the road and the sheriff's car pulling out and going the other direction.

"You want to pay for the ticket?" I said.

She stared ahead and sighed.

"Drive the speed limit and you'll never have to worry if you have enough money to pay a ticket," I said.

We pulled up to the school one minute before the bell rang. I waved and told the kids to have a good day. I had taught such a great lesson to my daughter, I thought.

I had to run a couple of errands, make a phone call, do busy work. As I headed home the clock felt like it was slipping away. Not enough hours in the day.

About halfway home I noticed a car behind me, pretty far behind but zooming. Lights on top of the car. My stomach clenched. I looked down at the speedometer and let off the gas slightly. I wasn't going that far over the limit, but I was over.

I knew the officers were out today. I knew it. I saw it. I told my daughter about it. And here was the nice officer in the car right on my tail. Numbers began turning in my head. How much would this cost?

He followed me for a while. An unnervingly long time. I came to a turning area I figured this would be the place where he'd hit the lights and pull me over. I was prepared for it.

But he just kept following. Maybe he was running my plates. Did I remember to renew my registration? I wanted to stop and hold my hands up. "I give up! I was going 5 mph over! Please, take me in now!"

I gave my turn signal at a big cross street. He gave his turn signal. Maybe I had committed some crime I couldn't remember and he was going to nab me. Shoplifting? Nothing I can remember. I didn't put my cart back once at Target and still feel guilty. Maybe it had run over someone.

I gave my turn signal again and slowed. I turned and he gunned his engine and raced past me. Sigh.

What I told my daughter earlier was true. For both of us.

"Can you pass him?"

Deadpan. As if she had the power to move heaven and earth.

I glanced at her. Not too long. I might have swerved. I glanced back at the road and the sheriff's car pulling out and going the other direction.

"You want to pay for the ticket?" I said.

She stared ahead and sighed.

"Drive the speed limit and you'll never have to worry if you have enough money to pay a ticket," I said.

We pulled up to the school one minute before the bell rang. I waved and told the kids to have a good day. I had taught such a great lesson to my daughter, I thought.

I had to run a couple of errands, make a phone call, do busy work. As I headed home the clock felt like it was slipping away. Not enough hours in the day.

About halfway home I noticed a car behind me, pretty far behind but zooming. Lights on top of the car. My stomach clenched. I looked down at the speedometer and let off the gas slightly. I wasn't going that far over the limit, but I was over.

I knew the officers were out today. I knew it. I saw it. I told my daughter about it. And here was the nice officer in the car right on my tail. Numbers began turning in my head. How much would this cost?

He followed me for a while. An unnervingly long time. I came to a turning area I figured this would be the place where he'd hit the lights and pull me over. I was prepared for it.

But he just kept following. Maybe he was running my plates. Did I remember to renew my registration? I wanted to stop and hold my hands up. "I give up! I was going 5 mph over! Please, take me in now!"

I gave my turn signal at a big cross street. He gave his turn signal. Maybe I had committed some crime I couldn't remember and he was going to nab me. Shoplifting? Nothing I can remember. I didn't put my cart back once at Target and still feel guilty. Maybe it had run over someone.

I gave my turn signal again and slowed. I turned and he gunned his engine and raced past me. Sigh.

What I told my daughter earlier was true. For both of us.

Published on February 21, 2012 10:00