Matador Network's Blog, page 2318

February 13, 2014

1 in 3 women will experience what happens to the man in this film [NSFW]

In a Women’s and Gender Studies class I took in college, my teacher had the men role play what it felt like to be cat-called. It was super awkward. French filmmaker Eleonore Pourriat takes things one-step further in her role-reversal short film, “Opressed Majority,” where men are seen as the victims of sexual harassment and sexual abuse, and the women, their oppressors. I felt uncomfortable watching a man go through many of the same issues I’ve experienced.

While I know plenty of men who treat women with respect, the sad fact is that there are people out there who act this way, and think it’s perfectly fine. Women are victimized based on their appearance, their choice of clothing, the things they say. According to the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault report, “nearly 1 in 5 women and 1 in 71 men have been raped in their lifetimes,” and nearly 1 in 3 women will suffer from some form of sexual assault.

Is this short film an eye-opener? It certainly resonates deeply with me, but the real question is, how does it influence the “oppressed majority?”

The post 1 in 3 women will experience what happens to the man in this film [NSFW] appeared first on Matador Network.

MatadorU Student of the Month: Jan

ONCE A MONTH, MatadorU faculty members get together to spotlight one standout student from a pool of faculty- and student-nominated weekly selections.

MatadorU Travel Writing and Travel Photography student Ana Lenz was selected as our very first Student of the Month for 2014. We sat down with her recently to learn more about about her experience taking both the Writing and the Photography courses concurrently, and the unique set of challenges she faces as a student for whom English isn’t her native language.

Congrats on being our first MatadorU Student of the Month for 2014! Tell us about yourself!

I was born and raised in Mexico. I currently live in San Miguel Allende, a small city in Central Mexico.

I’ve always been interested in the many expressions of art and I knew I had to find a profession related to it. Writing, cinema, photography, and architecture were in my mind. In the end, I chose to study architecture, but I’ve never stopped writing and learning about cinema and photography.

Right now, I work at an architecture studio in San Miguel Allende. My work there allows me to take some time off whenever we finish a project. I invest that time in fulfilling one of my biggest sources of joy in life: travelling.

By now, I have collected enough travel stories, pictures, and practical information, so this year I’ll start my own travel blog. This is one of the reasons why I enrolled in MatadorU, I want to make a professional blog, with stories worth reading.

Photo by January’s Student of the Month, Ana Lenz

What kind of stories do you hope to share with the world?

I feel a huge curiosity about human beings. They absolutely fascinate me.

Last week, I went to The Harmandir Sahib — The “Golden Temple” — in Amritsar. It’s where Sikhs guard the Adi Granth, the Holy Scripture. I entered the Gurdwara, the place where the Adi Granth is guarded. Everyone is allowed in, no matter which religion, sex or race they are.

There was this man who saw me and invited me to sit next to him while he chanted. At first sight, one might think we have nothing in common, right? He is a Sikh, while I don’t belong to any religion. We were born and raised on opposite sides of the world. He is at least forty years older than me. We don’t even share a language. And yet, he invited me to sit next to him, shared his chant with me, and said: “Welcome.” Then, we looked in each other eyes and smiled. In that instant, I knew that despite being very different, we shared a common humanity. With that gesture, he called me a human being and I called him a human being.

Those ephemeral instants that happen when we travel are very moving to me and are the ones that make all the tiredness and problems of travelling worth it. Those are the kinds of stories I want to tell: stories of the humanity we all share.

On your profile, you mentioned an upcoming trip to India, Nepal, and Bhutan. Do you want to tell us a bit more about your trip?

That’s right! I’m actually answering this interview at a rooftop restaurant in Agra, with a very interesting view of the life on the streets and on the other rooftops: kids juggling with ropes, women washing clothes, men drinking hot chai, loud motorcycle horns, cows walking around, and monkeys climbing into the houses.

I felt a lot of curiosity about India: its history, cultures, religions, traditions and social structure. I had to come and see it with my own eyes.

I didn’t come to document something in particular, I just wanted to learn as much as possible. India is its own fascinating, complex and frustrating universe. So far I’ve learnt a lot.

You’re enrolled in both the writing and photography courses. What inspired you to enroll in both courses?

Writing and photography can be complementary subjects. You can create art with words as much as you can create art with light, or as in my profession, art with space. If a piece of travel writing is complemented with great photography, or viceversa, then it becomes more complete. I enrolled in both courses so one could complement the other.

They have both also enriched my daily life. Because of the Travel Writing course I’m more aware now of the little details that surround my routine. Life doesn’t pass me by so easily now. And because of the Travel Photography course, I’m more aware of light and space, which enriches my profession as an architect.

What’s been the most challenging part of your MatadorU experience so far? Do you have any favorite parts?

The most challenging part has been writing in a language that isn’t my native one. I have to spend time translating words and looking for words I don’t even know to finally get a result that just doesn’t sound as I wanted. The structure of both languages is very different, so not only I have to translate the words, but I also want to make sure those words make sense, and that can take many hours.

But the great part of this is that I’m improving my language skills a lot, so not only I’m learning about Travel Writing and Photography, but also English.

My favorite part has been the feedback with the MatadorU faculty. Their knowledge has improved my writing and photography skills in many ways and I’m very thankful to them.

As one of our MatadorU students for whom English isn’t your first language, do you have any advice for students who are in a similar situation?

MatadorU is definitely attainable for non-native English speakers. I think it just might take a bit more time for them to finish the course, but that’s it.

My advice for them is to read as many books, magazines, newspapers, etc. written in English as possible, and watch movies without subtitles to get used to the way people really talk.

If they struggle, I’ve found that the native English speakers in the MatadorU community are really cool people who are willing to assist each other, so you can ask for a little help and connect with them on the way.

Student of the Month honorees are selected based on not only the quality of their work, but the progress they’ve made throughout the course, the effort and enthusiasm they show during their MatadorU journey, and their willingness to support and help their fellow students. Check out MatadorU.com for more information about our travel writing, photography, and filmmaking courses, and to learn how you can join Ana in our community of travel journalists from around the world.

The post Meet the MatadorU Student of the Month: Ana Lenz appeared first on Matador Network.

On Salt Lake City's 'snow culture'

Salt Lake City in the snow. Photo: Andrew Smith

1. The science

A wonderful phenomenon called the “lake effect” is a major contributor to the champagne snow Utah is famous for. Cold air moves over the warmer water of the Great Salt Lake, water evaporates into the clouds, and more snow falls on the mountains. The science is complex, but the result is localized and intense storms that can double predictions and keep the snow culture floating for days.

Jim Steenburgh, Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Utah, states that lake-effect snow’s “negative impacts are in terms of snarling traffic and potentially closing schools…. And then there are the positive benefits for Utah skiers, which is a deep powder day that boosts our winter sports economy.”

Lake-effect storms account for about 8% of Salt Lake precipitation during the winter. Depending on the snow year, that’s 30 to 50 inches per season. If the forecast says 5 inches, I’ll call my friend and bring dinner to his slope-side cabin. I may wake up to 3 inches, but there’s a good chance it’ll be 13 instead. Underestimating the power of the lake is a mistake you only make once.

2. The student culture

Photo: Brandon Dalton

With multiple colleges in the greater Salt Lake area, individuals come for school and study around their snow schedule. It’s more or less a sanctioned thing — the University of Utah runs a direct bus from campus to the resorts, and every mountain offers major discounts for students. We come for school, get hooked on the snow, and continue the balance for as long as possible.

I landed here eight years ago as a transfer student, drawn by a quest to find the closest nursing school to a ski resort. Pre-nursing courses were demanding, but by taking the occasional summer course and loading my fall semester, my winters were surprisingly free. On busy weeks, you’d find me with a pathophysiology book on my lap, crammed with three other friends in the back of a Subaru as we made the trek up canyon. An hour and two chapters later, I’d step out of the car less stressed and ready for another amazing day of skiing with friends.

3. The professional culture

From Black Diamond to Doppelmayr, many big names in the ski industry call SLC home. When your job is on the mountain or based around it, work becomes play and the ski lovers stay. The perks aren’t bad either. Free lift tickets and food, gear discounts and guided adventures — working in the ski industry pays back. You may not be the richest, but you’ll have the support of a community that trades hookups for the important things, like beer, food, and friends.

4. The work-play balance

Salt Lake City is the epitome of work meets play. With the mountains so close, the balance becomes easier here than maybe anywhere else in the country. I’m a nurse and I date an engineer. We both work 40 hours a week and still get 70+ amazing days on snow each year. With a little extra energy than most, we night ski 1-2 times a week and ski every weekend.

Out of work at 5, take the bus home, change, pack the car, grab a snack and caffeine, drive to Brighton, and ski from 6pm to 9pm when the lift closes. Dinner and drinks up canyon (at Molly Green’s, Solitude, or a friend’s cabin) or Thai takeout on the way home. When it’s this easy to make skiing your way of life, there’s no reason not to work and play in the same day.

5. The ridiculous accessibility

The Wasatch. Photo: vxla

There are 14 resorts within a few hours of SLC, and 11 within one hour. It takes about 45 minutes from standing downtown to sitting on a chairlift, half of which is a beautiful canyon drive. With an international airport five minutes from downtown, you can’t help but laugh when you land from Hawaii or LA and find yourself waist-deep in powder the same day.

From my house it takes about 10 minutes to get to the airport driving, or 30 minutes on the new Trax line. I can enjoy a leisurely brunch, grab a friend from the airport, stop by their house and drink coffee as they flick off their flip-flops and grab their ski boots, and make it to the mountain by early afternoon. There are few feelings greater than skiing with fresh sand and sea in your hair.

6. The rich history

Skiing has been an integral part of Utah since pioneers first settled here in the 1840s. Milling and mining led people up canyon, and 60 years later the first ski resorts were born. Founders such as Sverre and Alf Engen and K Smith turned their passion for skiing and the Wasatch Mountains into the current-day Alta and Brighton ski resorts. Old men whisper from the original walls at Alta Lodge, and black-and-white photos hang in most resort centers. They remind us of the dedicated mountain men who founded this lifestyle we love, and encourage us to continue living it to the fullest of our potential.

7. The powder flu

The “I might be ‘sick’ tomorrow” because it’s dumping snow is a more tolerated excuse here than in most cities. If you’re lucky enough to have friends who live up canyon, or live up canyon yourself, the impromptu sleepovers and carpooling phone calls happen faster than you can say “powder day.”

If the forecast calls for snow, I’ll start or be included in a 5-10 man text chain days before the storm actually hits. I’m lucky enough to have amazing friends in multiple near-slope locations, and the topics are always where to stay, who’s driving, and what to bring. We try to plan and work together 80% of the time. The other 20% is reserved for the all-powerful powder panic. Planned or not, my coworkers and boss know about my obsession with snow. This makes them surprisingly understanding when I ask to change shifts or come in late after a powder morning. I work hard when I’m at work and choose my days, but the snow support I feel in times of need is an unparalleled attribute that only a snow culture provides.

8. The community

Photo: dennis crowley

United by a common love of mountains, snow, food, drink, family, and friends, we come for the powder and stay for the community (and more powder). Nothing beats the yips and hollers of your favorite people enjoying a run, or the ‘cling’ of cocktail glasses at the end of a good day. The stomp of skis waiting for first chair at Brighton, the sound of avalanche bombs ringing through the tram line at Snowbird.

Salt Lake is a community bound by the love of snow and a happiness that is present on every content face on the mountain — sitting at Alta Lodge, feeling that euphoric exhaustion you can’t describe, and knowing the person across from you, holding a cold beer and eating free appetizers, feels it too.

Welcome to the community. Snow + Skiing = Happy People, Happy Friends, Happy Life.

This post is brought to you by Utah, home of The Greatest Snow On Earth®. With 11 ski resorts less than an hour from Salt Lake City International Airport, there’s plenty of powder for the perfect ski vacation.

This post is brought to you by Utah, home of The Greatest Snow On Earth®. With 11 ski resorts less than an hour from Salt Lake City International Airport, there’s plenty of powder for the perfect ski vacation.

The post 8 ways Salt Lake City’s ‘snow culture’ makes skiing a way of life appeared first on Matador Network.

February 12, 2014

The Brazilian approach to funk music

Rio funk, known as funk carioca in Portuguese, owes its name to the North American groove-music genre. But history has it that DJs and MCs from the initial baile scene, particularly Furacão 2000, got the beats from both electro and Miami bass, filling it with generous doses of dirty tricks. The result is fun, bizarre, and always original as fuck — even when stealing from others.

For years now, funk carioca has essentially been the soundtrack of summer in Rio and sings the life of the favelas and local communities — hence the level of violence and sexuality in the lyrics that would put off even Miley Cyrus.

Funk’s local popularity shows no sign of vanishing — as proved by this current map of bailes in Rio. It’s also influenced a host of new genres around the country, most notably the ostentação (as in: ostentation), sort of a younger brother from São Paulo. Inspired by the reality and aspirations of economically ascendant Brazilians, funk ostentação in general talks about money and what it can buy.

Here’s a little of what Brazilian funk can teach you about the country.

“Megane,” MC Boy do Charmes

Coming from Santos, birthplace of ostentação, this is the MC who, alongside visual producer KondZilla, created what’s considered to be the first “ostentation” aesthetic, emulating the lifestyle portrayed in North American rap and RnB music videos: expensive booze, cars, motorcycles, clothing, jewelry. As they say, “Out with the HK, in with the Citroen.”

Consumerism is an important part of the economic boom Brazil has experienced in the past decade, and few forms of expression pay homage to it more than funk ostentação.

“O Gigante Acordou,” MC Daleste

Daleste was born in São Paulo and rapidly became a strong musical role model. His lyrics told of love stories, of childhood, and daily life in poor neighborhoods. He was huge on Brazilian YouTube and also at São Paulo’s bailes. Tragically though, Daleste was shot on stage during a gig last year. He was 20 years old.

Before being killed, Daleste wrote and recorded “O Gigante Acordou” (“The giant awoke”), about the street protests that happened all over Brazil in June of 2013, giving voice to the enormous dissatisfaction regarding the country that some prefer not to speak about. But his lyrics also told about the feeling of hope, that a day will come when all is going to get better.

“Beijinho no Ombro,” Valesca Popozuda

Former gas station attendant and proud owner of a rearguard that would send Kim Kardashian home to cry, the inimitable Valesca has sung about how she’s “met Lula at the favela, and he couldn’t take his eyes of my ass,” among less printable lyrics. The unbelievable music video for “Beijinho no Ombro” (“Kiss on the Shoulder”) tries to imitate the ‘diva + dancers’ modus operandi of so many North American videos, while Valesca sings about how she wants her inimigas (enemies) to live long enough to watch her rise to fame.

The current economic climate has done wonders to Brazilian self-esteem. We feel deserving of copying foreign styles and fashions while maintaining our local jeitinho.

“Na Pista Eu Arraso,” MC Guimê

After overcoming many difficulties, subculture kids and their Brazilian funk now proudly mix external references — the North American looks and moves, the sunglasses, the Instagram selfies. It’s time to sing their success, to claim the prestige of the VIP area, the expensive champagne, the hot girls walking at their side.

Guimê is probably the biggest name in ostentação (he prefers to call it just “funk”) and, as anyone who’s survived difficult times, he has loads of self-esteem. Sexism and presumption — it’s all here.

“Envolvência e Quebradeira,” Bonde do Passinho

Passinho (small step) dancing was born at the bailes, a mixture of movements from funk, frevo, capoeira, and hip-hop. This video shows a day in the life of some kids as they go to release new music at the baile. From the competition between dancers came this bonde (group) to show how funk is evolving to something else.

This is where the mix of influences and genres, so characteristic of Brazil, reaches new heights. The cultural sampling and popular creativity are explicit in the passinho, a dance that, as many Brazilian streets, is not for amateurs. [image error]

The post The Brazilian approach to funk music appeared first on Matador Network.

Notes from a big wall climber

All photos: Ben Ditto

The 1200′ sandstone formation known the climbing world over as Moonlight Buttress stood proud in the sun’s radiant light. Four different parties were cast about the wall; it looked like a game of connect the dots. Which rope connected which person to what and where. Spring Break was in full effect, and it seemed like the university kids were chomping at the bit for this route. Some seemed to be going at it full wall style with multiple bivys, others were in day aid parties, and some even seemed to be trying out the free climbing. For many this wall is people’s first — for me it wouldn’t be a first, but it would be a sort of milestone in my climbing career.

Every big wall free climber I know has either ticked this iconic line, or it’s on their list. It had been entered into my queue some years back when Kate Rutherford and Madaleine Sorkin made the first all-female free ascent. At the time my wall experience was limited. I had not long moved from the South to California and was still cutting my teeth on the granite in Yosemite. I’d previously really only been a sport climbing and bouldering aficionado.

As the years progressed, so too did my climbing experiences and my knowledge of how to manage these bigger stones. I made mistakes, I achieved goals, and I found myself with a fortunate quiver of climbing partners. Each partnership had taught me something different, and it became more and more evident to me that climbing partnerships took on a deeper meaning than someone willing to belay you. They were relationships; I relied on my partners to be on time, to be positive, to be supportive, to be patient, to be willing to let me make mistakes and figure them out, to belay just so, and on and on. And I felt I was expected to do the same. A lot of talk had been had with different people about possibly teaming up for this wall, but in the end my real dream was to do it with another female, all free.

As a single woman it has never been terribly hard finding a partner, but the majority of them have been males, and since these partnerships start to take on the characteristics of a relationship, this has always come with its struggles. One or the other usually starts to develop emotional feelings, and these are either addressed and reciprocated or it turns really ugly. Imagine your climbing partner crush belaying you on your project after you’ve just told them how you feel and they stare back blankly at you saying, “Oh, I thought we were just climbing together,” — there goes the send and your self-esteem.

At some point one or the other can become jealous if they go off climbing with someone else — questions about what the partnership really is come into play, and it’s at this point that things either continue along or break off. Once the partnership has subsided, it’s time to move on and find a new partner. Usually this is a fun and trying time — you try a little of this and you try a little of that, but eventually what you decide on is a steady partner who’s willing to be there for those alpine starts and late-night descents.

I’ve been fortunate in my years in Yosemite to climb with local legends like Surfer Bob, Big Fall James, Jake from the Gate, little Sue McDevitt, and Jobee Whitford. I became partners with Ron Kauk, one of the most influential people of my life. I even met my husband, Ben Ditto, climbing Yosemite’s walls in 2009. We form a great partnership and relationship. We’re compatible in our climbing and hold similar aspirations, from sport climbing in Europe to free climbing big walls.

In the last years, some of what we’ve had the opportunity to do together was free climb several walls in a day, including: Lotus Flower Tower – VI 5.10d, Cirque of the Unclimbables; Original Route/Women at Work – VI 5.12R, Mt.Proboscis; Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome – VI 5.12b, Yosemite Valley; Romantic Warrior – V 5.12b, The Needles; and the West Face of Leaning Tower – V 5.13, Yosemite Valley. But through all these times I still longed for a partnership of a different kind. I longed for my female counterpart — the other chick who could crush the cracks, climb the steeps, and dominate the boulders, someone who knows how to build anchors, haul a bag, and generally speaking, hold their own. I craved the experience of facing challenges with someone of similar build so that we could learn from each other. I had become friends with Kate Rutherford, and I admired the partnership she had with Madaleine — I wondered where my equivalent lay.

All my searching and waiting led me to Sandra early in 2012 — she was strong, she was well-rounded in many aspects of climbing, she was petite, and all in all seemed solid in character. We met at the boulders, and I think it was love at first sight. Through the last year we became more acquainted with one another — we developed a repertoire, we helped push one another and supported each other on numerous projects and ambitions, and soon we established a tick list together. Moonlight Buttress was pushed to the top of this list. It seemed like all my dreams of finding a compatible and capable female partner were coming true. Very often she and I would blow off our significant others in order to climb together. Our partnership walks the line of a relationship, and in the winter of this year when Ben and I were leaving for three months to climb in Europe, I was nearly heartbroken to have to leave her behind. We kept in touch weekly about our climbing experiences, our latest sends, our struggles, and the upcoming training we would be doing when I returned home — we kept the Moonlight vision alive.

Finally, in mid-March we found ourselves racking up in Zion National Park. Our first climb of the trip together was Shunes Buttress – IV 5.11c. It went great; we climbed well together. We kept it slow and steady as we dialed in our systems and belays and got the feel of how we would be moving together in the sandstone wonderland. Some days later, we were crossing the icy waters of the Virgin River and making our way to the base of Moonlight. There were a few parties at the base and on the intro pitches; a few different times in the day we found ourselves waiting on them. As the time ticked on, we maintained a positive outlook — we were giving our best onsight attempt, and we were doing it together. Unfortunately, as the pitches kept coming so did the waiting, and by the time we were standing underneath pitch 8 we realized we would be doing a bit more waiting and not topping out in the light — I wasn’t very interested in sorting out the last hard pitches via headlamp in the dark, and so we made the decision to rap the route. It was okay, as both of us had fallen on some of the climbing below.

As we descended down to the sandy, vegetated slope via headlamp, we came up with a plan to return in two days and try again. But early on the morning Sandra and I were due to go back, she got word that her mother was really ill and was urged to go be with her. We both knew previously that this could be a factor in our plans, and we had been playing it fast and light. But that morning, as she stood in the door of my van, tears in her eyes, I knew she was not only sad about her poor mother but also about our unfulfilled dream. Life is present. and with that comes responsibility — she needed to leave and I understood completely. I was so sorry to hear the news and very sorry to lose her as a partner.

Plan rewrite started for me. Mason Earl, a fellow First Ascent athlete, was coming into Zion in a few days to meet up with us for some work for Eddie Bauer. He had climbed the route the previous year, but I wondered if he would be interested in doing it again with me — he said he would be down. I waited for him to arrive and off we went.

Moonlight is such an iconic route in equal parts climbing quality and scenic beauty. Ben really wanted to shoot us on the route, and Eddie Bauer had expressed to us that they really wanted portaledge shots — so we took this idea into consideration when we made a plan for our climb. We decided we’d do the wall with a bivy, which would allow us to start late in the day and have us climbing the crux dihedral in the shade. We started late on Sunday and blasted through to pitch 7, the infamous slot pitch. On my attempt with Sandra, I had fallen here a couple of times — this time I climbed it efficiently and effectively. I belayed Mason up and the photographers met us there. We set up the ledge, cooked dinner, enjoyed the sunset, and got some great shots.

We slept on the wall that night with the canyon to ourselves. It was stunning. I thought about Sandra several times. I was enjoying the experience of being on the wall with Mason, but at times I could tell he was a bit bored. He was there for support and I appreciated it greatly, but it was the same old thing. I was once again climbing with a stronger male partner who could jam his .5 fingers snuggly into the 1-inch cracks — we could hardly relate at times.

The next morning, Ben wanted to get shots of me on pitch 8 in the first light. It was cold, but I racked up and set off anyway. I was freezing and moved slowly. Looking down at the belay, I could tell Mason was freezing, too. I made it about halfway up when I was totally numbed out in both hands and feet and slipped out. I lowered down, cleaned the gear, and rested a minute. I tried to thaw out and tried again, but it was a similar experience. I got too cold, and it was a brutal warmup. I thought to myself that we should have just kept climbing the day before — that it would have been easier then — but so it was and here we were.

I slipped out again — this time flash pumped. I continued up to the belay and asked Mason if I could try again, and he didn’t mind. So I lowered down, cleaned the gear, and rested for about 10 minutes. The gauzy haze of clouds was parting and it was warming up. After some food and water I set off again. This time I made it no falls. The rest of the route went smoothly enough and we were topping out by midday. I had become one of the women on a short list who have free climbed this route. I was grateful to Mason for playing along, but I was saddened a little not to be high-fiving with Sandra.

The route had been a challenge for me. It’s not the hardest or longest thing I’ve ever climbed, but it offers up three pitches in a row of one of the single hardest sized cracks for me. Being 5’0″ and with small hands, the 1-inch cracks never truly provide me with any solid jams — it’s neither fingers nor hands, and there’s no real finesse to climbing that size.

I was psyched to climb through those pitches, and I think I even learned some slight nuances in technique thanks to Mason. It was a great accomplishment and I’m thankful to have experienced some time there with Sandra. In the end I know it was a stepping stone on our journey together as partners, and while we didn’t get the chance to complete this one together, I know where to find a solid female to hold the rope for me and do her fair share of getting us up the wall. [image error]

* This post was originally published at Thoughts and Things from a Bird’s View and is reprinted here with permission. All photos courtesy of Ben Ditto.

The post Notes from a big wall climber appeared first on Matador Network.

This is the most gruesome ‘Stay in School’ commercial, what was Australia thinking?

This ‘Stay in School’ advertisement is the most gaga film-clip I have ever watched. Has Australia completely lost the plot? Let me please offer you a massive warning before watching this, it is next-level graphic. Don’t press play until you have your area hazard-free — no cups of tea, nor open water bottles, and make sure you have finished your breakfast; or it could end up all over your computer screen. [image error]

The post This is the most gruesome ‘Stay in School’ commercial, what was Australia thinking? appeared first on Matador Network.

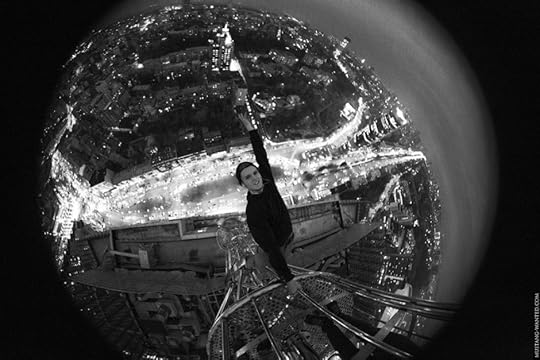

Urban free climbing insanity [pics]

“Free climbing” is an absolutely horrifying extreme sport where urban daredevils climb to the top of skyscrapers or other tall buildings and dangle from them with no harnesses. One of the most prolific (and impressive) of them is the Ukrainian free climber known as Mustang Wanted.

All photos courtesy of Mustang Wanted

Mustang Wanted at one point worked as a legal advisor, but has since decided to pursue a career as a professional stuntman. He says he doesn’t feel any sort of ball-shriveling terror at the stunts he pulls. “Sometimes I think that I am a robot,” he said in an article for The Daily Mail. “I do not feel anything.”

He says, “Death is not the worst thing that can happen. Everyone dies — but not everyone lives the way they want.” While you’d think, “That’s the way a guy who’s gonna be dead soon would think,” Mustang Wanted has been doing this for over a decade, and has yet to be injured.

Before we go any further, we should note quite strenuously that you should not, in any circumstances, do this. Hopefully that doesn’t need to be said, but this is enough of a trend for a documentary to exist about it. So unless you are either a professional (you aren’t) or immune to the effects of gravity (you aren’t), don’t do this.

That said, it makes for some pretty breathtaking photography.

What perhaps makes this more incredible is that not only is he dangling from buildings and spires, he’s orchestrating this photography at the same time.

Incidentally, this is illegal. You know…because of the whole dying thing. But presumably, if you aren’t afraid of death, you aren’t afraid of getting arrested. There are, of course, times when this could feasibly be dangerous to more than just the free climbers, such as when they do stunts on bridges.

Oh right, I forgot — on bridges on fucking bikes.

Aside from the obvious requirement of gigantic brass balls, a few other things are needed to do this. First, crazy finger strength.

Also ankle strength:

Balance:

A tremendous amount of trust in the people you’re climbing with:

And flair:

For those of us lacking those things, we can at least enjoy the fruits of one daredevil’s labor.

Mustang Wanted has also produced a series of videos of his stunts, including this sphincter-clenchingly terrifying compilation. Dude be crazy.

The post Urban free climbing: The new extreme sport you shouldn’t try [pics] appeared first on Matador Network.

10 things you definitely didn’t know about money

I SPEND MONEY every day, but never once have I really stopped to think about what exactly I’m exchanging with the world – not to mention, where it’s been before I touched it. I won’t give away exact details, but from this video, I realized that:

Money is disgusting (0:07)

Donald Trump is a greedy idiot, or has a wicked sense of humor, I’m not quite sure (1:04)

Queen Elizabeth II is way more popular than Benjamin Franklin (1:15)

Some people actually spend money, to buy more money (1:50)

Even people who make money can make mistakes (2:24)

What did you learn?

The post 10 things you definitely didn’t know about money appeared first on Matador Network.

Why are some travelers such a$holes?

Photo: Guian Bolisay

The first time I went on an international trip I was 26 and alone. Like most first-time travelers, I was overwhelmed with emotion — everything from anxiety and fear to excitement and disbelief that I was actually embarking on the journey. Three years later, every time I plan a new trip, those similar feelings still wash over me.

With a freelance career in IT and writing, I’ve been lucky enough to live and travel anywhere I want and share my experiences through travel blogging. My goal as a travel writer has always been to help people that want to travel but don’t yet understand that international travel is not only possible but also affordable. I often recommend places throughout Latin America or SE Asia for a first international trip based on my own experiences; yet, travelers who have made traveling their lifestyle will give me shit for talking up, say, Costa Rica or Thailand.

The travel community is and always has been pretty supportive. I love hearing about other people’s trips or adventures. I’m always on the lookout to put a new destination or activity on my bucket list, and I’ve met some truly wonderful people both on the road and through travel forums and blogs. What I don’t understand, though, is the general jadedness or negativity that comes from other travelers at times. It’s like if you talk about your time in Tanzania and how it was a life-changing experience for you, there’s always someone who wants to talk about how Tanzania is becoming too touristy now, and how Chad is where “the real Africa is” — as if you couldn’t experience important reflections on your own life simply because you were traveling a well-worn route.

Here’s the thing — we, as humans, don’t receive medals for achieving certain life accomplishments: getting engaged, having children, or collecting passport stamps to incredibly exotic locations, just to name a few. I understand seasoned travelers are constantly on the hunt for the next unbeaten path — if such a thing really exists anymore — but for new travelers, exploring a place like Costa Rica is an adventure and an experience outside their comfort zone. In America, where less than 40% of our citizens have passports, just having the opportunity to travel abroad once in a lifetime is an accomplishment in itself to many people.

I get annoyed by their pretentiousness over how people should or shouldn’t be while on the road.

Often I’ve been told what “real travelers” do and don’t do: “Real travelers don’t use guidebooks,” “real travelers don’t get overly excited about traveling to a new place,” “real travelers don’t use backpacks…” And the opposite: “Real travelers only use backpacks and never suitcases.” I’ve always thought of travelers as those with a positive and open-minded spirit, but I can’t help get exceedingly annoyed by those who drench their conversations with pretentiousness over how people should or shouldn’t be while on the road.

Maybe it’s naïve of me, but I don’t believe there’s any right way or wrong way to travel. If people are putting themselves out there and are eager to learn and experience other cultures, I think that’s just fine. Call it silly, but yes, I still get excited every time I confirm flights somewhere, or when I’ve left one country and I’m about to head somewhere else. If there’s no genuine rush of excitement over traveling, why even travel to begin with?

And furthermore, why act so jaded towards others, as though our enthusiasm is childish? Isn’t one of the greatest experiences of traveling the fact that it allows us to have a child-like experience in certain ways? I don’t care how many journeys I embark on throughout my life — I will always approach my travels with an open heart and open mind.

If you’ve reached the time in your travels where traveling no longer gives you what it once did, and you find yourself becoming cynical, at what point do you realize that, as hard as it may be to admit, it’s time to go home — wherever that may be — or that you should simply stay put in one place for a while? Don’t be “that guy” that has to one up everyone else at the table with how many passport stamps you’ve collected, then condescend to someone else for being thrilled over traveling somewhere you’ve already been and decided to discard for whatever reason.

There are no rules when it comes to traveling. Let’s let people go wherever they want in whatever way they find comfortable for their life, and let’s continue to find inspiration in foreign lands and different cultures — the whole reason we were driven to travel in the first place. [image error]

The post When did travelers become such a$$holes? appeared first on Matador Network.

8 facts about Brazil's World Cup

Photo: Ingo Wilges

BRAZILIAN PRESIDENT DILMA ROUSSEFF might have said the country’s ready “to host the Cup of all Cups,” but not all Brazilians are partaking in the World Cup frenzy. This is what I think every gringo should know before making the trip this summer.

1. Workers have died at World Cup construction sites.

A 55-year-old Portuguese man died earlier this year during the construction of the World Cup stadium in Manaus. He’s not the first: Two men died before him at the same site. There have also been deaths at the future Itaquerão stadium, in São Paulo, when a roof collapsed.

2. There are no express trains / subways from the main airports to city centers.

Yes, there’s a plan to build a train connecting Guarulhos International Airport to São Paulo, but it’s not happening this year. The date’s been pushed to 2015 — just in time for the 2016 Olympics that will be held…in Rio. Great timing, Governor!

3. The stadiums are either unfinished or plagued with problems.

As I’m writing this, only half of the 12 stadiums have been completed. The others have had their opening dates postponed, and one may not get finished at all. Of course, Brazil has demanded more money in order to complete construction. A lot more, in fact: The previously approved budget of $2.8 billion has been raised 285% — which means the 2014 World Cup stadiums alone will cost more than $8 billion.

4. Taxi drivers don’t speak English, or Spanish.

Public transportation is a problem all over the country. Trying to get from point A to B is an everyday problem in most big Brazilian cities. The best way to get around is by taxi, but you’d be surprised how drivers aren’t ready to deal with foreign-language passengers. So learn a few Portuguese sentences and hope for the best — Brazilian people in general are much more honest and eager to help then their governments.

5. Brazil is one of the most expensive countries on Earth.

Really. People are obsessed with making money here.

6. Fireworks turn deadly.

It happened last week and is all over the news: A cameraman was shot in the head by a rocket know as a rojão. It’s not the first and most likely won’t be the last time something similar happens. It’s a dangerous form of entertainment people seem to enjoy. You’ve been warned.

7. Brazilian torcidas are among the most violent in the world.

Heard of the British hooligans? Well, their cousins are in Brazil.

8. Crime rates keep rising.

There’s little an unprepared and ill-equipped police force can do when prisons are already filled beyond capacity. Crime rates in Rio, for instance, just keep going up. And then, as if the situation weren’t dangerous enough, ordinary people are taking up the banner of ‘vigilante justice’ — with tragic results.

The post 8 things you gringos should know about the 2014 World Cup in Brazil appeared first on Matador Network.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers