Matador Network's Blog, page 2257

June 12, 2014

How to piss off a New Mexican

Claim green chile as your own.

Nothing has united New Mexico so fully under a single banner as the Colorado-trying-to-steal-our-claim-to-green-chile scandal. Green chile is the state vegetable of New Mexico. It is actually called “New Mexican green chile.” New Mexico has a state question: “Red or green?” And that question is referring to your chile preference. And you think you might be able to say it doesn’t belong to us? Nice try. We have little else as our claim to fame, so we’ll fight for this one to the death.

Spell ‘chile’ wrong.

There is chili and then there is chile. Chili is that spicy(ish) mixture of meat and beans that goes great with cornbread. Chile is the delectable plant that defines New Mexican cuisine, and also happens to be the largest agricultural crop in the state. Confuse them and you’ll be sure to make a New Mexican twitch (and probably correct you).

Assume we’re not American.

New Mexico does happen to be one of the 50 states of America. Take a look at a map and try and pretend to be a bit more educated, please.

Say, “You’re from New Mexico? Your English is really good!”

See above. Just no.

Eat at Chipotle or Taco Bell.

If you’re in New Mexico, for the love of God, don’t eat this crap. You can get indigestion from these any day of the week in any other place in the country. Seriously, eat a freakin’ smothered burrito from a local joint while you’re here, will you? I could give you a hundred recommendations.

Refuse to try our green chile.

As you may have guessed by now, New Mexicans take their chile quite seriously. If you’re visiting the state, or have a New Mexican friend who wants to cook you one of their favorite meals from home, don’t be that person who just “doesn’t really like spicy food.” We’re not trying to shove it down your throat, we just want you to taste what goodness we enjoy every day.

Assume it’s all just like Phoenix here.

A lot of people seem to believe all of New Mexico is some vast, brown, blistering desert (no offense, Phoenix). But actually, the terrain varies greatly from one end of the state to another. Yes, there are areas of desert, but there are also millions of acres’ worth of national forests, and, being at the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, much of the northern half of the state happens to be mountainous. Don’t underestimate our geographic diversity.

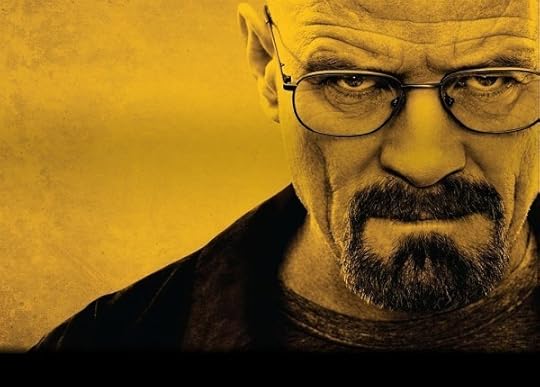

Act like you know what it’s all about here because you’ve seen Breaking Bad.

No, I don’t know anyone who cooks meth. No, I’ve never seen a meth lab. And no, not all of my friends are just like Jesse Pinkman.

Assume we’re all from Albuquerque or Santa Fe.

I realize this happens with a lot of states. The biggest cities get all the love. But there are other cities with their own populations, and they deserve some awareness, too.

Ask us to say something in Spanish.

Or one of the eight Native American languages in the state, for that matter. Nobody likes feeling like an animal on exhibit. Just because someone is from New Mexico, and even if they can speak a language other than English, does not mean you can just command them to say some meaningless phrase in that language for your entertainment.

This post originally appeared at NewsCastic and is republished here with permission.

19 signs you're from FL's Panhandle

Photo: Janine

1. You actually know which part of Florida the Panhandle is.

Hint: It’s the part touching Georgia and Alabama.

2. You’ve heard someone say, “If it’s called ‘tourist season,’ then why can’t we shoot them?”

Tourist season is basically all year. Spring break, summer tourists, then the snowbirds flock. They bring in lots of revenue, but they’re also really, really annoying.

3. You’re either a Gator or a Seminole. There are no in-betweens.

College football is a huge deal in the Panhandle. Family members won’t speak to one another if their team loses and the other’s wins. If you’re from the Panhandle, you probably bleed garnet and gold.

4. You know Florida gets cold.

We get frosts. We get below-freezing temperatures sometimes. It’s traumatic. Having to actually wear socks.

5. You’re a time traveler.

The Panhandle is split between two time zones: Eastern and Central. So you can celebrate New Year’s twice.

6. You hate BP but you love its dirty money.

Most of the Panhandle’s business is based around the Gulf of Mexico, and people mistreating our ocean are not our friends. But hey, thanks for the new garage.

7. You avoid Panama City Beach at all costs during March and April.

While the antics of your spring break are funny and entertaining for us locals, we mostly just want you to leave.

8. You can’t stand snowbirds either.

Please go the speed limit. Please stop telling me how charming my accent is. Please go back to the frozen north you came from.

9. You drink sweet tea every day.

With every meal. And when you go somewhere that doesn’t serve it, you’re appalled and confused. How can you not have sweet tea? What I am supposed to drink? WATER?

10. You have a grasp of basic manners.

We hold open doors. We wave. We’re friendly folks.

11. Until something pisses you off.

Ain’t nothing scarier than a pissed-off Southerner. We take things personally.

12. You know the horror of yellow flies.

If you have to ask…

13. You’ve attended more than a few hurricane parties.

Because what else are you going to do for the next few days besides get drunk and eat crap?

14. You don’t question the “beach time warp.”

Have I been here for ten minutes or ten days? I could check my skin, but it started burning as soon as I stepped out the door.

15. But you also know “the beach” isn’t the only source of water-themed fun.

Despite all of the wonderfulness the Gulf has to offer, you know that the springs, rivers, and lakes also make the Panhandle awesome.

16. You own more than 7 bathing suits.

It’s all about the water.

17. You understand Florida is a big state.

So you’re going to South Florida for some unknown reason? Enjoy your hot, humid, 6-hour drive. Going to the East Coast? Enjoy your 6-hour drive.

18. You take your seafood very seriously.

Apalachicola oysters and big Gulf of Mexico shrimp…know what I’m saying?

19. You’ll come back.

Sure you think you’ve moved away “for good” and to “see the world.” Good for you. See you soon because the Panhandle doesn’t let go easily.

The only DJ in the bush

Rifle: check, guitar: check. All photos: Author

Lemon Creams were being sold at a dollar for three packets behind the concrete counter. They formed part of a wall of essentials in the shelved backdrop of the shop, a corner of which was dedicated to bright panels of clothing. Breakfast was half a pack of the cheap, barely zesty biscuits in a dusty car park. Early drinkers sat on the porch of the bottle store swilling brown barrels of Chibuku (homebrew) in their hands like giant Kinder eggs.

Binga is one of the remotest districts in Zimbabwe, and some of the locals share symptoms of neglect or persecution found in many exploited indigenous cultures the world over. Binga town itself seems to have been forgotten in the ’80s by the rest of Zimbabwean society, buildings like cadavers stuffed with the lowest grade of cigarette, brandy, and basic foodstuffs. The local Tonga people lived in the Zambezi Valley, which was flooded when the Kariba Dam was constructed decades ago to provide the nation with power. The locals were forced to move from the area in which they’d farmed, fished, and lived for centuries and now live on higher land, most without the power generated a few miles up the lake, with their huts still built on stilts far away from the water’s edge. A relic of the past, haunted by the present.

Lake Kariba

We called Marv to see how far away he was, and he told us to hop back in the car and keep going. His initial directions of, “You’ll see a bridge, then a hill, then a big tree on your right,” were hard to pinpoint on a road with hundreds of big trees, dozens of bridges, and no ‘hills’ to speak of.

Marvin Mutangara describes himself as “a nonconformist son of great African parents who taught me to lead and not to follow. Of the Soko Vhudzi Jena totem, whom I believe to be one of the first families to settle in modern-day Zimbabwe. Today I am Beat Viking.” Marv is a DJ, passionate conservationist, wildlife expert, and adventurer. He’s lived around Zimbabwe and in parts of Europe over the years and has been involved in a Ferris wheel of craziness along the way. Some of the more off-the-wall highlights of his life include “overlanding safaris in sub-Saharan Africa; speaking Dutch, DJing, and selling banana beer at festivals in Europe; horse riding in random places in Zimbabwe, including a solo Tonga Trail ride across one of the country’s most treacherous and barren regions, avoiding lions and surviving on avocados and biltong (dried meat) for days on end.

“The inspiration behind the Tonga Trail horse riding challenge was based around my work with lion conservation and the realisation of the dramatic decline in our lion population over the last 30 to 40 years. I planned to challenge myself by seeing if that decline was noticeable whilst following the route on horseback. The ride itself didn’t really go along the route as I had planned it, but I was able to determine for myself that the report of a massive decline was sadly a reality. I was glad that we didn’t have many encounters with lions because the two encounters (one in Hwange National Park and the other in the Mavuradonha wilderness) will live with and define me as long as I live. The trail was a confirmation that there is nothing better than personal action, and it challenged me to be more definitive with my goals.”

The perfect place for any hammock

A view of Marv’s ‘villodge’

After meeting us on the road, wrinkled spliff between his morning grin, Marv took us to his new home. For the last couple of years he’s been building his ‘villodge’ from scratch. Forging the roads on 33 hectares of land, plotting where to put his fish farm, where he’ll build accommodation for volunteers and eco-travellers, and conspiring to host an epic party in the bush on the banks of one of the largest manmade lakes in the world.

Marv is immersed in the daily hardships of the Tongan locals: “It’s not glamorous at all, but people live with pride…unfortunately that pride is eroding due to a lack of definition.” Marv’s thatched hut has three rooms including a kitchen, bathroom, and main living area. To get by he’s been delivering truckloads of freshwater fish to the nearest large towns and cities hundreds of kilometres away. “I live in a hut and eat fish three times a week. I’ve started my own vegetable garden that hopefully won’t be trashed by hippos. There’s enough to survive on if you are able to trade, but I must say that without the support of my love, and my family in Zimbabwe and Norway, I would not be where I am today. There are birds, bees, and bats. Spiders, scorpions, and snakes. The greatest view. Hippos, crocodiles, and elephants. You have to be alert and alive to survive and appreciate the future potential.”

Armed with vegetables, live animals, guitars, and a rifle, he explained that he is “militant in many ways, and my rifle is the best business card and shows my commitment to personal security. People understand guns and what they do. As a sound junky the boom is a great bonus too. The guitar shows the contrast of my inner conflict and means that I have something to do when I’m rolling solo. The idea of busking and playing covers of anything from Tracy Chapman, Bob Marley, the Killers, and the Doors around the campfire has been something I have always enjoyed. So my guitar playing is more just for personal entertainment and allows me to feel like Sixto Rodriguez in Searching for Sugarman. Do it out of passion and not for the pay. My ancestors would be proud that I still carry the chordophone with me. It is, after all, a bow of sorts. If you look up my surname in a real Shona dictionary it means two things, a thick porridge and a monochord. When you’re secure everything sounds better, even your set.

Marv in his humble kitchen, a generator in the foreground for emergencies

“On my first visit to Amsterdam I had the pleasure of meeting and hanging out with the boys from Rush Hour Records. That was my first introduction to modern-day DJing and the use of vinyl in this amazing art form. My dad and mom had tons of vinyl when I was a kid, and I can remember that we would often stop daily house chores whilst my mom organised a dance-off involving brothers, sisters, cousins, maids, and gardeners. So music was definitely the thing growing up, and vinyl was not a foreign object. The idea of dancing was just a form of expression to the grooves, beats, and rhythms.

“For me, DJing involves the use of sounds to try and communicate to a part of humanity that we have come to forget. I always try to imagine a time when my ancestors were using their latest technologies to communicate their appreciation of being on the planet. That is what my DJ set is about; I try to confront people with an atmosphere that is not always comfortable but that can be received by the ears and the body. During this process I try to play and mix music, sounds, anything I can get my hands on that you’ve probably never heard or that is classic and not commercial. The feeling is tribal. The only thing plastic in the DJing world is those using controllers and computers to try to simulate what can only be done by using turntables and a mixer.”

Marv plans to build more huts and accommodation to fulfill the ‘villodge’ dream where tourism is not the point but, rather, a sense of and space for human connection, community, and development. As he sat in the shade of the overhanging thatch I felt immense pride in the fact that he’d already come this far, and it was invigorating to witness the beginnings of something from the heart, borne out of passion and hard work.

Marv surveying his land

“It’s fucking HOT and there’s a cool villodge in the making. The Tobwe River Villodge is the finest example of what can be achieved if you love what you do. The idea of being African and building a uniquely Zimbabwean village lifestyle that represents thought and vision incorporating modern innovations is exciting. With all the available ideas that are progressive and that fit with the land, people and culture are the lifeblood of the project. The realisation of the abundance of resources is the starting point on the road to success. Then it’s important to find the right people and investment partners, and that process takes time. It is, therefore, important to begin somewhere — that is where I am now, in entry phase.

“The objective is clear and so are the challenges that are unique to Zimbabwe’s investment climate, economic, and political challenges. I operate by believing in the resources and the wealth that is tangible — all I need to do is be exemplary in progress and set up a showroom of equipment, innovation, and ideas. I intend to build a positive culture that preserves the identity of the people and the place. The positive traditions, which define the Zimbabweans of the future by understanding the ancient appreciation of nature and humanity. Civilisation is in need of definition; having a mobile phone does not make you civilised, being able to feed yourself is. Having a belly full enough so that you can hang up your bow and arrow and turn it into a monochord to play a simple tune is innovation. It is this kind of example that is translated from understanding my family name that makes me believe in the beauty of Zimbabwe and the need for minds that are poised for definitive progress.”

Marv, aka Beat Viking, is currently DJing and cross-country skiing in Scandinavia. For DJ bookings or to visit him and work at the Tobwe River Villodge, drop him an email at trvoffice@gmail.com.

9 North California farmers markets

Photo: Robert Couse-Baker

CALIFORNIA PRODUCE ACCOUNTS FOR much of the color and variety we see in grocery stores across the US. Over 400 different crops are grown in the state, including what amounts to nearly the entire national supply of artichokes, walnuts, kiwis, and plums. Farmers operate in most regions of California, and there’s always something in season no matter when you visit, so farmers markets are staples of any trip to the state. To learn more, check out CA Grown.

1. Ferry Plaza Farmers Market, San Francisco

The scene at San Francisco’s Embarcadero marketplace takes “bougie” to a whole new level — though, admittedly, McEvoy’s olive oil does taste like your tongue is being deliciously massaged with a satin ribbon. The farmers market in the Ferry Plaza out front is deservedly praised as one of the best in the country.

It’s known for its diverse array of organic-certified, locally grown produce and unbeatable artisan provisions (hello, cheese), but never fear, meat eaters — there’s also plenty of charcuterie delights. Come on a Thursday or Saturday for hot food from local chefs and restaurants. Tuesday is also a market day. Welcome to foodie heaven.

Photos: Michele Ursino

2. Marin Civic Center, San Rafael

There are actually two different markets held at this impressive site, the final architectural masterpiece of Frank Lloyd Wright. On Sundays, the Civic Center Farmers Market is one of the largest in the state, hosting around 200 local farmers during the summer months. Pick a bouquet from the colorful array of flower stands that decorate the market (sunflowers are my favorite) and grab a loaf of fresh-baked bread for a picnic by the duck pond.

On Thursdays, a slightly smaller market attracts area chefs shopping for fresh, local ingredients. It’s also a pretty sweet spot to grab a weekday lunch from one of the many food vendors onsite.

3. Thursday Night Market, Chico

Free bike valet. If this weren’t enough to attract a loyal crowd, downtown Chico’s Thursday Night Market also moonlights as a street festival with live entertainment. Spanning multiple streets, it’s a grand summer affair that attracts folks from nearby locales such as Paradise, Gridley, and Orland.

If not for the certified-organic produce and artisan wares, come for the live music — and bring the whole family. From the kid zone to the food trucks and street performances, the market appeals to anyone who enjoys a night of good company and even better food. Things kick off at 6pm and run till 9.

Photo: Sharon Mollerus

4. Point Reyes Farmers Market, Point Reyes Station

Housed in Toby’s Feed Barn (summer Saturdays 9am-1pm), this West Marin market takes “farmer” to a literal level. Like its host city, the Point Reyes Farmers Market is far from pretentious and doesn’t lack for quality despite its smaller scale.

Situated in the heart of fertile West Marin, the quaint market offers an uber-local menu, with provisions hailing from the likes of Bolinas and Tomales. If you don’t like cheese (i.e., you have no soul), try hometown favorite Cowgirl Creamery. Five bucks says it turns you into a believer.

5. Old Monterey Farmers Market, Monterey

From the gyro to the baklava, each booth at the Old Monterey Farmers Market provides a taste of a far-off place. To best enjoy the market’s worldly quality and delicious foreign offerings, stroll its streets with an open mind towards trying new delicacies (a strong appetite doesn’t hurt either). As for local fare, Monterey’s fresh fruit and pastries speak for themselves.

Tourists and locals mingle at this popular event, so you’re sure to make a new friend waiting in line for the kettle corn. Find it all on Tuesday afternoons, 4-8pm (summer) / 4-7pm (winter).

Photos: John Morgan

6. Kensington Farmers Market, Berkeley

Berkeley’s health nuts get their weekly fix at the farmers market at Colusa Circle in Kensington. From the usual assortment of leafy greens and dried fruits to hand-pressed olive oil and artisan ciders, this market dabbles in a bit of everything. Local artisan coffee Catahoula also makes an appearance.

While praised for being vegan-friendly, the market also hosts Fat Daddy’s BBQ stand, which you should not miss. Go to work on some ribs as you make your way to Tom’s Best Ever Granola, where you can fulfill your Berkeley cliché with delicious homemade granola. The Kensington Market takes place on Sundays from 10am to 2pm.

7. Arcata Farmers Market, Arcata

On summer Saturdays, locals head to Arcata Plaza for live music and organic food bliss. If you’re not hungry, just check out the local bands or enjoy the excellent people watching — hippies and environmentalists galore. The only thing sweeter than the local honey is the loyalty of the sun, which always seems to be shining on market days. With its hard-to-beat local products (vegetables, fresh flowers, homemade fudge), Arcata is the cream of the crop of farmers markets this far north.

Photos: Franco Folini

8. Davis Farmers Market, Davis

Utilizing its advantageous position in California’s agricultural heartland, the Davis Farmers Market is the definition of hyper local. Spanning 4th Street in this college town, the market has mastered both quality and quantity. It’s also open year round, rain or shine (Saturday 8am-1pm + Wednesday afternoons).

Kettle corn is a favorite, or satisfy your sweet tooth with some local honey. Grab a jar and some freshly baked French bread and enjoy an impromptu picnic at nearby Central Park.

9. Healdsburg Farmers Market, Healdsburg

This market veteran was one of the original Certified Farmers Markets in California. In addition to showcasing a feast of fresh food, Healdsburg offers some of the finest wine the 707 area code has to offer. It takes place Saturday mornings and Wednesday afternoons, summer and fall.

Though less of an all-day event than some of the bigger markets, Healdsburg is a great mix of tasty treats, artisan crafts (handwoven tea towels!), and charming local vendors. Which makes it the ideal blend of Northern California’s best qualities.

* * *

Our friends at Visit California asked Matador how we #dreambig in California. This post is part of a series we’re publishing to answer that question. Click here for more.

Our friends at Visit California asked Matador how we #dreambig in California. This post is part of a series we’re publishing to answer that question. Click here for more.

June 11, 2014

Map of school shootings since 2012

Photo via Everytown for Gun Safety/Mark Gongloff

IT FEELS LIKE ALL I’VE SEEN on the news lately are stories related to guns. It’s getting to the point where I can’t even keep up with the shootings and the different circumstances behind them. School shootings seriously hit home for me though; as a teacher, I’ve been present during lockdowns, and it’s definitely not easy to keep a group of students calm when police officers are yelling in the hallway, looking for suspected criminals.

I won’t lecture you about the divergent sides of America’s gun control issues, even though this data comes from the Everytown for Gun Safety. I’ll just leave you with this map, and you can form your own opinions. It marks the 74 locations that have experienced a school shooting since the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012.

French vs. English soccer fans

Photo: Anthony Beal

Cliquez ici pour lire cet article en français et profitez-en pour nous “aimer” sur Facebook.

1. Location Location Location

Imagine standing shoulder to shoulder in someplace like Hull, watching your local team scraping for a nil-nil draw in the rain. Nothing tops that. Well, unless you’re in Monaco, with well-healed enthusiasts chanting, “Oui! Oui! Allez! Allez!” on a warm Mediterranean evening in September. They might not know the score, but they sure know their Chardonnay from their Sauvignon Blanc.

2. Singing for the win

When the pipe band starts to play, the teams stand to attention with passion flowing through their veins. A song rings out to unite a nation; unfortunately it’s the British anthem, “God Save the Queen.” Whoever wrote it clearly had not imagined it sung in a football stadium. Don’t get me wrong — the Queen should be saved, but she may need something a little more upbeat.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise,” praises violence and few people know its meaning, but the chorus sure is fun for fans to belt out!

3. Thirty years of hurt

So the song went in 1996. English fans still imagine that each World Cup is theirs to lose. They won it once in England in 1966 and most likely never will again. But still they dream every four years. It’s almost time to change the song to “Fifty Years of Hurt.”

France, on the other hand, never expects to win. They did, though, to the surprise of the fans in 1998. Now let’s see what happens this year!

4. A bridge too far

French fans are blessed with some of the world’s best players to cheer, many of whom are the sons of immigrants. These were people who dreamed of a better life for their children, and I guess they didn’t dream of England. Who can blame them!

5. Golden balls

Actor / designer / celebrity / underwear model and footballer David Beckham is adored by fans all over Europe, and not only in the fashion houses. The French don’t seem to have any “golden balls” (or balls of any kind, really) on their side of the Channel.

6. A tale of two cities

London and Paris are the two largest metropolitan areas in Europe. English fans can boast several top teams to follow in their fair city, and these teams are cheered with passion and pride. Paris has only one top team. Fans began to follow them with equal passion, especially after a Saudi billionaire bought the club and the world’s best players.

And 6 similarities

1. Sugar daddies

The top clubs in both England and France are all owned by Russian or Middle Eastern billionaires, and the fans are not complaining. This foreign investment has allowed clubs to buy the best players in the world and pay the highest salaries. This is great news for fans of certain clubs and not so great for others — the losers.

2. Eric Cantona, the rebel who would be king

Most English fans harbour a dislike for this French footballer. He made his name in England for his skill with the ball and for karate kicking a fan! French fans too resent Eric for admitting that he has supported England and not France since he retired…and to top it off, he’s from Marseille.

3. A song for all seasons

Both sets of fans love nothing more than chanting songs at football grounds. There are football songs for any outcome, triumph or despair. Most songs are passed down from generation to generation and have been sung for years. Sometimes French fans even translate famous English songs. They seem to be lacking imagination and creativity over there.

4. Managers

English fans are very afraid of the unknown foreign manager, and often turn to name calling. One manager is still called ‘the Professor’ because of his glasses (it doesn’t take much to be considered an intellectual in Albion). There are similar stories in France, where one national team coach became the “Star-Man.” He actually picked the team based on horoscopes. Horoscopes!

5. Hooligans and hoodlums

Both sets of fans enjoy a good old riot, though reputations suffered in the ’80s due to a number of tragic disasters. English fans prefer to keep it in and around the stadiums, while French fans set their cities on fire.

6. In the limelight

In the rest of the world, the private lives of the players are respected, but not so much in England or France. French football fans have their daily “serious” newspapers dedicated to football. One in particular was even the decider of the European Footballer of the Year (Ballon D’or).

English fans may not have the same level of prestige, but where else would you read about a footballer allegedly paying a porter at a hotel $330 to buy him cigarettes, or another attending the wrong club’s Christmas party? These are the topics of the day, people.

How to botch your trip to Orlando

Photo: Ben Andreas Harding

1. Swallow the wave pool water at Typhoon Lagoon.

The wave pool at Typhoon Lagoon is awesome. It’s a little known fact that you and your friends can actually rent the wave pool out after the park closes to surf for three to four hours. Just don’t swallow the water. Band-Aids, random garbage, and human fluids have been marinating in it for hours. There’s a reason it’s so chlorinated.

2. Forget your E-pass.

Known as Sunpass to the rest of the state, the E-pass is your ticket to avoiding a road rage incident on toll roads in the area (408, 417, and 528, that means you). If you’ve rented a car, procure one. Stay in those “E-pass only” lanes. Otherwise, you’ll be scrambling to find cash in a long line of cars (in which every other driver is doing the same). It’s just about as fun as it sounds.

3. Go to any theme park during Easter weekend.

Contrary to popular belief, locals do go to Disney World, Universal Studios, and Islands of Adventure. What’s the catch, you ask? They avoid going on holidays – Easter weekend, Christmas vacation, and MLK Day are out. Your reward for going on those days anyway? One-to-two-hour lines and spending too much money on Mickey-shaped chocolate-dipped ice cream. Hell, don’t go in the summer either. The heat index will guarantee you have a miserable time.

4. Go to a bar near UCF.

It’s difficult to find a reason to say you should. The only thing you’re going to find is underage college students attempting to party. There will be cheap drinks. There will be awkward dancing. There will be puking in the bathrooms. You’ll live without all of that. There are exceptions, but friend, just go downtown.

5. Think “downtown” means Downtown Disney.

Downtown Disney is a decent replacement (not really) if you don’t have a car to get around the city. However, Downtown Disney is not the droid you’re looking for. The one you want is about 18 miles northeast — you’ll find great bars, clubs, restaurants, and more (without Mickey’s face emblazoned across any of their facades). Besides, you’re visiting Orlando, not Disney World. This should go without saying.

6. Get on I-4 between 4 and 6pm.

Interstate 4 is a paved, 132.3-mile stretch of hell. Yes, it does get you across the state, which is an impressive feat for one road. But come rush hour, do your best to be anywhere but on I-4, especially if you’re anywhere near the Conroy exit. You’ll have plenty of time to stare at Orange Blossom Trail or the Holy Land Experience, depending on which part of the giant traffic jam you’re stuck in.

7. Try to feed the swans at Lake Eola.

There is little to say regarding the activity. People will tell you to bring bread to feed the swans — great idea, not-so-great execution. The swans might bite you. Those evil creatures might even try to steal the sacred Publix sub you just purchased to eat lakeside. The former is painful. The latter is a grave offense.

8. Go to the Mall at Millenia on a Saturday.

Everyone will tell you that the Mall at Millenia is a great place to get your shopping done. This isn’t false. Advice-givers often fail to mention the possibility of you reaching your boiling point (and simply driving away in disgust) in an attempt to find parking at the mall on a weekend. Save yourself the headache and park far, far away. If you do manage to find parking near the mall’s entrance, you’ll step inside to droves of tourists and locals congesting walkways and stores. At least there’s air conditioning inside. This applies to the outlets as well.

9. Assume Orlando stays warm all year.

Orlando gets hot. It also can get pretty damn cold. 29 degrees Fahrenheit may sound like a normal Massachusetts winter day, but occasionally it’s an Orlando winter day as well. Check the weather forecast before you show up. Pack the right clothing. Otherwise, you’ll be spending your vacation budget on new clothing at the mall — if you find parking.

10. Never leave tourist-land.

Orlando is a spread-out city. There’s a lot to see and do. Once you complete your theme park marathon, make sure to venture out — no, not Sandlake Road. Check out the smaller towns in the Greater Orlando area. Drive around Oviedo. Visit Gotha (and make sure to stop at Yellow Dog Eats for a bite). Go to Windermere. Take a walk in Winter Park. Explore. Get lost. Find some culture.

5 adventures in Southern Utah

IF YOU’VE DONE ANY RESEARCH into visiting Southern Utah, you’ve no doubt come across its five national parks: Arches, Canyonlands, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, and Zion. Situated on the Colorado Plateau, the landscape in this part of the state is high desert, mesas, sandstone, rivers, and canyons. For me, coming from the forested mountains of British Columbia, it was like entering an alien world.

While the parks are destinations in themselves, worthy of days/weeks of exploration, there’s a lot of land just outside of them that also warrants your close attention. Over three weeks this past spring, my partner and I traversed Southern Utah from east (Moab) to west (Springdale). We hit most of the national parks, but our best memories come from outside their borders. Here’s how we explored these areas.

1. Mountain biking Moab’s lesser-known trails

Biking at the Bar-M area near Moab. All photos: Author

I know. Biking in Moab isn’t exactly under-the-radar, but it’s important to point out the variety of biking available to all skill levels. It’s not just for the hard-cores heading to the world-famous Slickrock Trail. That one was beyond us (as it is many people). But we did get on our bikes and onto some really fun single-track that fell into the beginner-to-intermediate range — cross-country, not downhill.

The Bar M Loop is north of Moab and great for a quick ride. There are some mildly technical sections, but overall can be just fun and cruisy.

Biking in Dead Horse Point State Park was also a highlight for us (video above). On their Intrepid Trail system they have riding for every skill level, and the views off of vertical cliffs into the canyons below are staggering. For more mountain biking ideas in and around Moab, DiscoverMoab is a great resource.

2. Canyoneering outside Zion

I’d briefly heard about canyoneering before I went to Utah, but it was still unclear to me what it was all about. After trying it out, I realized the answer is twofold: A) exploring, and B) problem-solving. Because canyons are always changing (e.g., from flash floods carrying and depositing debris), even the guides are always a little unsure of what to expect. This is part of the excitement.

There are different levels of canyoneering, ranging from basic hiking to routes requiring very technical skills and knowledge of ropes and climbing. Some super popular options in Southern Utah include hiking the Narrows in Zion and doing a guided tour of Fiery Furnace in Arches (this one requires pre-booking). But there are so many canyons to explore, and a plethora of guide companies to show you the way, even if you have no experience.

The video above was shot in a canyon outside of Zion that was classed 3BII (rope required for single pitch rappels (3); a bit of running water/pools (B); half-day exploration (II)). Our guide, Bailey Schofield from Zion Adventure Company, really pushed us to figure things out for ourselves, and allowed us to make the decisions (although she’d be quick to point out potential dangers). It was a very empowering experience.

3. Rock climbing near Moab

Nate, owner of Moab Desert Adventures, placing gear on Ancient Art.

There’s a famous rock climbing area near Moab called Indian Creek. You may have seen pictures of it: a polished, smooth red wall with a big crack and someone wedging into it (for example). This is for experienced climbers with a lot of technical knowledge.

But you don’t necessarily need to have rock climbed before to get to some amazing places in the area. There are lots of guide companies that will take you where you’re comfortable. We chose a different area near Moab, and picked out a sandstone tower called Ancient Art. While we have plenty of climbing experience, our guide, Nate Sydnor of Moab Desert Adventures, told us he’d previously guided the climb with someone who had zero experience.

Not to say it’s an easy climb — it’s not. It’s actually petrifying, as you can see in the video above, but if you’re at an appropriate physical level, have the right fortitude and the right guide, it’s possible to climb a route like this and make it your first ever.

4. Rafting the Colorado

I’d been rafting a few times before in British Columbia, but seeing the desert landscape from the water was an experience I really wanted to have. We did a half-day trip with Moab Adventure Center (you can do full- and even multi-day trips as well) on the Colorado River just outside of Moab.

In early April, the section we hit was mostly a gentle paddle down the river, taking in the immense red cliffs and listening to interpretive stories from our guide, but we did get to paddle through some bumpy sections, getting a good splash now and then and some adrenaline pumping. As you can see from the video, hopping into the water for a swim is also an excellent way to cool off from the intense sun.

5. Hiking in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

The “prize” at the end of the Lower Calf Creek Falls hike in Escalante National Monument.

Whenever I visit state and national parks in the US, it always dumbfounds me how many people don’t get out of their cars to enjoy a hike in nature. Even at peak visitor times, getting away from the parking lot is a great way to escape the crowds.

Hiking in the desert is such a different experience from hiking in the mountains of British Columbia. It’s amazing to consider the plant and animal life that thrive in such harsh conditions, and to get up close and personal with the unbelievable geological formations.

It would be a monumental exercise to list all the potential hikes in Southern Utah. Besides some of the trails in the national parks (like Delicate Arch in Arches and Angel’s Landing in Zion), one of my favourites was Lower Calf Creek Falls. The trailhead for this hike is located at the Calf Creek Campground in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, about halfway between the towns of Boulder and Escalante along the gorgeously scenic State Route 12. It’s one of the hikes featured in the video above.

This post was proudly produced in partnership with Utah, home of The Mighty 5®.

Why I've left Rio for the World Cup

Photo: Alobos Life

LIKE MANY TRULY MEMORABLE PARTIES, Rio’s World Cup celebrations look set to be a blast for everybody…except the hosts. As the world’s press whips itself into a frenzy over the forthcoming fiesta of beautiful beaches, beautiful butts, and the beautiful game, I’m getting the hell out of Rio de Janeiro before the first whistle blows.

With a day to go before kickoff, the city still looks like a construction site. Transport and building projects that were promised to be delivered in time for the Cup are months — if not years — away from completion. Attempts to throw a veil over the city’s horrific social problems have backfired, and violent shootouts between drug traffickers and “pacifying” units of military police have become a nightly occurrence.

This would have been my third World Cup in Rio, and by local standards the pre-Cup street decor is looking lackluster to say the least. The colorful football-related murals that traditionally crop up months in advance of the Cup are outnumbered by slogans such as “F*ck FIFA” and “Queremos Hospitais Padrao FIFA” (“We want FIFA-standard hospitals”). One mural downtown shows a yellow smiley face with a bleeding bullet hole to the head and the phrase “Bem vindo ao pais do copa” (“Welcome to the Country of the Cup”).

With the world’s attention on Brazil, and much of that attention centered on Rio, everybody with a political axe to grind is vehemently stating their case. Recent weeks have seen general strikes called by everybody from bus drivers and street cleaners to security guards and museum staff, as underpaid workers press the government for decent wages in a city where the cost of living is sky high and salaries are often shamefully low.

Police units decked out like Robocop with helmets modeled on Darth Vader roam the magnificent Zona Sul (the wealthy South Zone of the city, home to tourist hotspots such as Ipanema, Copacabana, and Sugarloaf mountain), while masked gangs of protesters that call themselves “Black Blocs” insist that “there will be no Cup.”

I’ve imagined what it will be like during the Cup, and I’ve decided I’m not going to be around to witness it.

There will be a Cup, and I have no doubt it will be remembered as one of the most spectacular of all time. But as the fans focus on partying on the beach and the press cameras focus on the teeny bikinis, those of us that live here will have to contend with hordes of visitors crowding an already overloaded public transport system, with already absurd food and drink prices bumped up still further to exploit the tourist dollar, and a whole host of day-to-day annoyances that will be overlooked as the city puts all its efforts into the Cup.

On a quick stroll through downtown a few mornings ago, I had to walk out into traffic three times to avoid three separate exploded pipes leaking sewage onto the sidewalk. Already-poor internet and phone connections seem primed to get weaker still as they struggle to contend with the influx of World Cup visitors.

Rio de Janeiro is a city whose ability to captivate is matched only by its ability to frustrate. A city of seemingly endless physical charms, it is also a city with a rich-poor divide that beggars belief, where social problems have long been overlooked in favor of creating an aesthetically pleasing city “para gringo ver” (“for the foreigners to see”).

It’s a city where crime is rife, where prices are high and quality low, and where the simplest and most mundane of tasks turns into a day-long adventure due to queues and endless red tape. (Want a new SIM card for your phone? First you’ll have to register your CPF (Brazilian Social Security number). Don’t have one? Good luck with that.)

For at least a year, locals have sighed and said, “Imagine na copa!” (“Imagine what it will be like during the Cup”) every time an overloaded bus has ground to a halt, a water pipe has burst, a supermarket queue has stretched into infinity. I’ve imagined what it will be like during the Cup, and I’ve decided I’m not going to be around to witness it.

I’m sure it will be a great party, but I’m going to sit this one out. Bring on my first World Cup in Buenos Aires!

Mapped: London property prices

Photo: findproperly.co.uk

Think you have enough money to buy a flat in central London? Think again.

Have a look at this interactive map; it may turn out that you can afford little more than the combined surface area of a few CDs and iPhones.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers