Matador Network's Blog, page 2199

October 7, 2014

Story behind the shot: Giza, Egypt

All my previous photos of the pyramids had been filled with traffic, tourists, and hawkers — busy, unfocused, common. I knew I needed to try something different. I decided I’d give the Giza complex another shot. This time I’d get there earlier, maybe try and make use of some bad weather, not just for beautiful light and stormy clouds, but also because it might keep tourists away.

I was right about the light. There were some fairly menacing dark black clouds with blue sky just poking through in places. But I was wrong about the tourists. Masses of tourists were still storming the main pyramids. I decided to ignore them and focus on the smaller pyramids, get up close, and use a wide angle. This was when I got “the shot” of the trip.

This image was different — it was a pyramid, the symbol of Egypt I wanted to get, but not a stereotypical ‘blue sky, sand, and bloke on a camel’ photo that’s all over the internet and travel magazines. At the same time not full of tourists, vendors, or busses. It had points of interest with the dark, angry clouds, a low, more composed angle, no tourists, and really nice light on it. I was amazed, later, that I was really the bloke that took it.

This isn’t the best image I’ve ever taken. Not by a long shot. But it was this image, and the trip as a whole, that, through a culmination of planning and experimentation and the development of my workflow, completely changed the way I approach my photography. The majority of photos I got from Egypt weren’t good at all, but the week was one of the most important learning curves in my photographic journey, and at the end of it — after hauling my gear across the country, sweating through innumerable t-shirts, being up early with the dawn, and up late researching day after day — I’d at least come away with this one photo. One photo to prove to myself I could do it.

Best apps for your Instagram photos

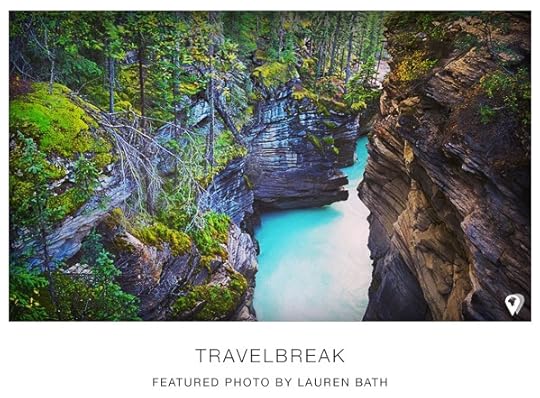

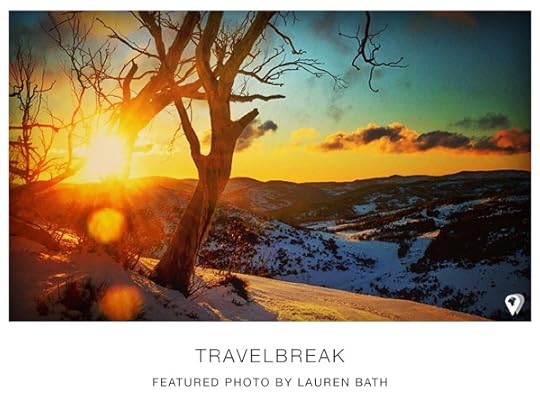

1. Lauren Bath, @laurenepbath

Favorite App: Snapseed

The first thing I do to any RAW image from my Nikon D800 is to open it in Adobe Bridge and make some adjustments to the RAW file. I then open it up in Photoshop and do some light editing there.

After I’ve processed my files in Photoshop, I sync them through to Dropbox to retrieve on my mobile phone. From there, I always use Snapseed. A mobile phone has a different monitor from a computer, so I use Snapseed to pick up the colors, contrast, and sharpening — and ready it is for Instagram!

Finally, I open my image in Instagram and use the filters provided to finish my shot off. I prefer Mayfair but also often use Rise, Hudson, and Valencia.

This may seem like a lot of work for an Instagram upload, but the work I do in Photoshop is to prepare a high-resolution image for my tourism clients and for Facebook.

2. Cara Llewellyn, @Llewllewtoo

Favorite Apps: Snapseed, VSCO Cam, Afterlight

I use the VSCO (Visual Supply Co) app for all of my initial photo editing. The filters are stunning, myriad, and easy to adjust within the app. My feed’s aesthetic is a combination of bright and faded, with buttery, almost matte-looking shadows that I achieve primarily with the F2 and M5 filters. I hardly ever use the filters at full power, usually opting to scale them back a few notches for a subtler effect. Since the majority of my images include people, the last step I do in VSCO Cam is adjusting the skin tone (a great free download option) to counteract the blanching effect of the filter. After I get the tones and colors where I want them, I export the image and open it with the Afterlight app. I’ve found that Afterlight has the best shadow options — perfect for really pulling out the matte black I love so much. I often straighten, crop, square, and tweak the brightness/contrast there as well.

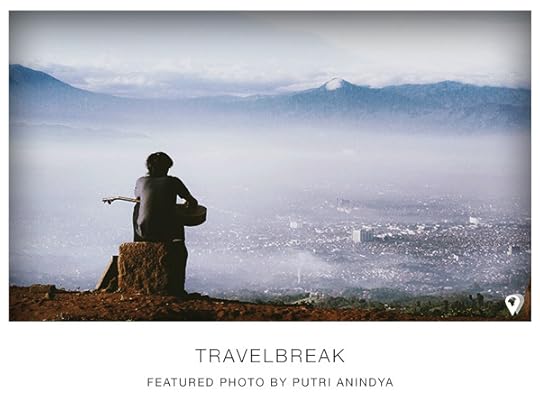

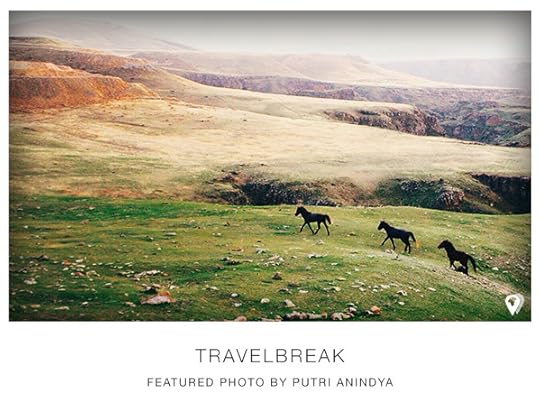

3. Putri Anindya @puanindya

Favorite Apps: Snapseed and VSCO Cam

My favorite photo-editing apps are Snapseed and VSCO Cam. Bonus, they’re free! I always do the basic edit in Snapseed then apply some gorgeous presets in VSCO Cam. I love Snapseed because it’s easy to operate; it’s like Photoshop in your mobile phone. So many great features for adjusting a picture. I love Snapseed’s Selective Adjust. It’s just awesome. The character of my photography is often defined by its mood. I love moody pictures. VSCO Cam helps me set the mood. VSCO Cam presets are beautiful — the result is just like it came out from Lightroom! I have all the VSCO Cam presets. I always try each one but usually end up sticking to G1, M5, M3, or HB.

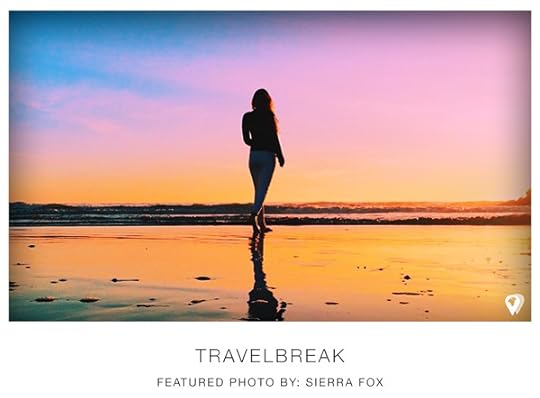

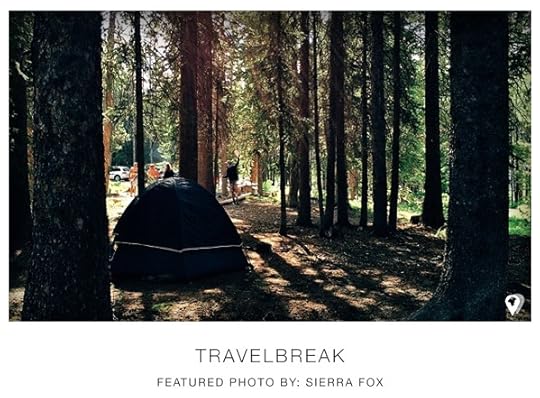

4. Sierra Fox @LilFoxx

Favorite Apps: VSCO Cam, Snapseed, and SKRWT

My favorite editing app for the iPhone is VSCO Cam, hands down. Not only does this app allow you to make adjustments to the image (such as brightness or contrast), but it also has a large range of filters that bring your photos to the next level. It can give your photos a crisp, minimal blogger feel with the S and N filters, or a film-like vibe with the F or E filters. This app is seriously magic.

I usually edit my photos first in Snapseed. It’s where I adjust the shadows and contrast and can use Selective Adjust to edit only small parts or details of a photograph. Then I take the photo into VSCO Cam to add filters and make any further needed adjustments (usually temperature, brightness, or highlights). I love VSCO Cam so much I bought almost all of the filter packages they offer (which is worth the few dollars!). Over time, I’ve developed an eye for what filter will look good on a picture, but I have a few favorites that are my go-to filters (F, C, S, M, E, and N). I try those out and then usually make a few adjustments here or there in the tools section of the app.

Another app that’s great for traveling and taking pictures of architecture or structures is SKRWT. This app can be difficult to learn but helps to perfect the perspective on an image. Sometimes, especially on the iPhone, when you take a photograph of a building it can appear warped because the lens is made for a wide angle (so that it can get more of what you see into the photo). This app helps to straighten the pictures back out to what they look like in person.

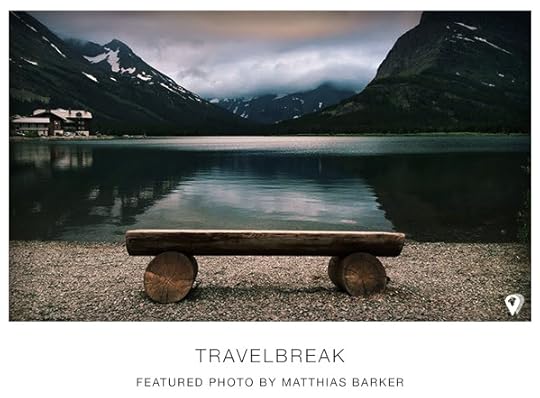

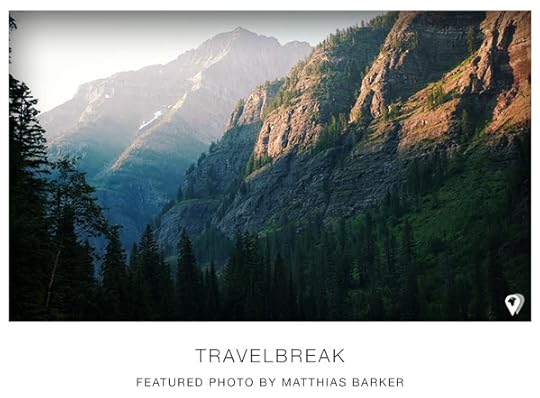

5. Matthias Barker, @matthiasjbarker

Favorite App: Snapseed

My favorite photo-editing app is Snapseed all the way. I love the control it gives you with your exposure, contrast, and structure. You can really control the depth of your photo and draw people in with your edit. To me, it’s the most organic and intuitive app on the market.

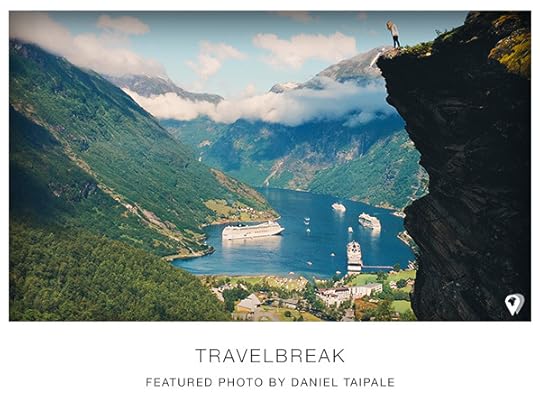

6. Daniel Taipale, @dansmoe

Favorite App: VSCO Cam

I’ve always loved film photos. Nowadays, when I shoot most of my photos in digital, I still want them to have a finished film look. VSCO Cam is an app for the iPhone that gives my photos this beautiful film look. The app is very advanced. I love how I can organize the tools and presets to my own order. This makes the app fast to use. It works the way I want. You can’t make your photos look too processed with the app; it just gives them a nice, clean faded look.

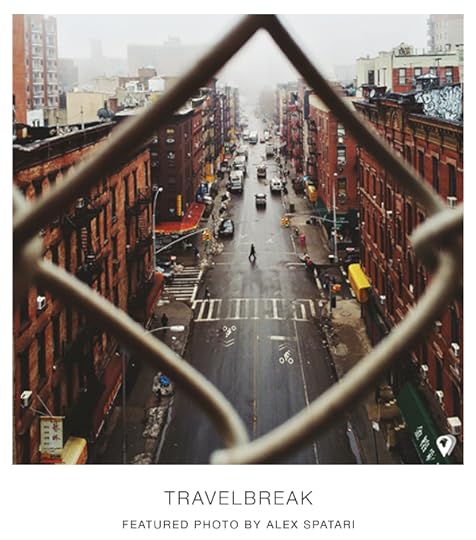

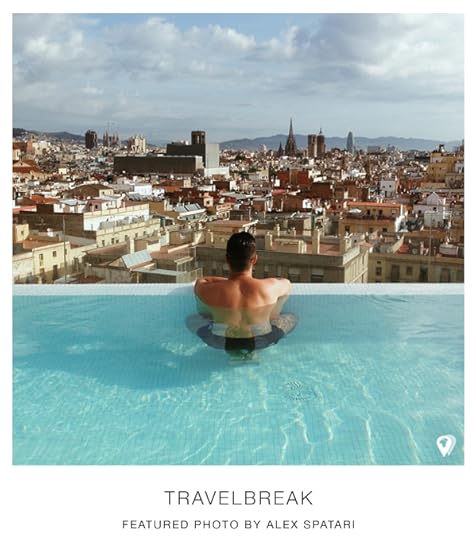

7. Alex Spatari, @spatari

Favorite Apps: Snapseed and VSCO Cam

My all-time favorite editing app is VSCO Cam. I discovered it about a year ago, and since then I use it for almost all of my pics. The best thing about it is its flexibility. It has a lot of different options, which gives you plenty of space for really great post-processing. And of course the filters! All of them have this amazing old film feeling, and at the same time the shot doesn’t look over-processed with them. The other things I like about this app are how you can organize your library and keep only the best photos from your phone. Plus it’s awesome how the creators of VSCO Cam managed to create the whole community around this app. I’d say it’s even become a lifestyle already. You should check their curated Grid — it has some really great shots on it! Regarding new options from Instagram — I like some of the features. Sometimes I add additional highlights or make the shadows lighter, and that’s probably it. I think these and other features were realized really well, and for those who think VSCO Cam is too complicated for them, Instagram’s editing features give them a lot of possibilities for post-processing.

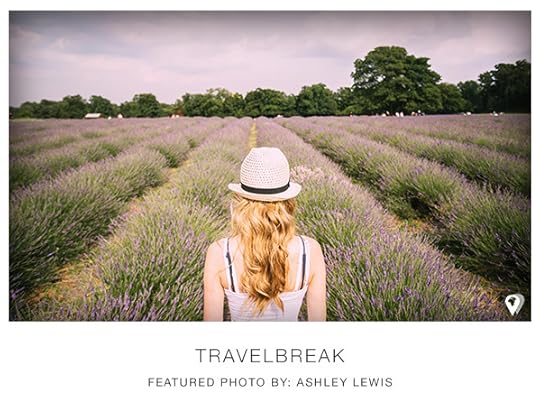

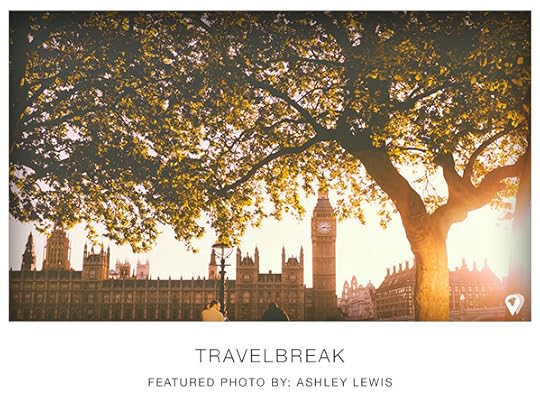

8. Ashley Lewis, @ash

Favorite Apps: Snapseed and VSCO Cam

You want me to pick one photo app? That’s just impossible! These days there are just TOO many photo-editing apps on the market. I couldn’t pick just one, but I can tell you about the two I use the most and why. The first app in my roster has to be Snapseed by Google. I use Snapseed right at the start of my post process. I use the Tune Image set of tools to clean up the saturation and contrast, lighten shadows, and adjust the white balance. I then add some clarity to secure the details and preserve sharpness. Second on my list is VSCO Cam. If you don’t know about VSCO Cam, then you’re definitely missing out on one of the best tools on the market to date (FACT!). I use VSCO Cam as an alternative to the Instagram filter set. My favorite presets are the F, T, and K filter sets. It’s hard to explain, but they provide that little bit extra to the photo, whether it’s fade, saturation, or tonal adjustments. For me, these filter sets really just add that final magic and polish to my photos.

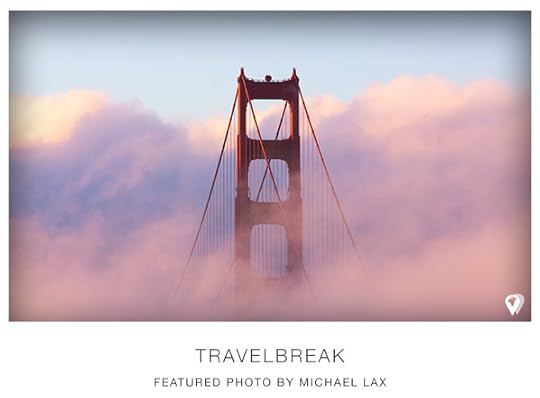

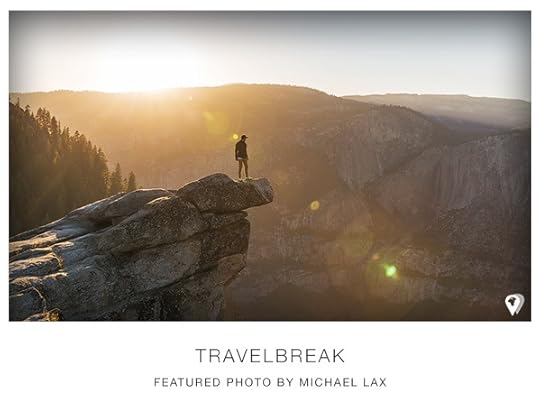

9. Michael Lax, @michaellaxphoto

Favorite App: Snapseed

My favorite photo-editing app is definitely Snapseed. It offers basic editing tools but also has some advanced features similar to Photoshop. One of the tools I use most in Snapseed is the Selective Adjust tool, which allows me to pick a specific area of the photo and only apply edits to that area. For example, your camera will often expose for the sky during sunset, which leaves your foreground looking too dark; this is where the Selective Adjust tool comes in handy. You can lighten up the shadows in the foreground without touching the beautifully exposed sky.

10. Christian Becerra, @throughthetinylens

Favorite Apps: Snapseed and VSCO Cam

I have two favorite editing apps, and they’re pretty much the only ones I use. The first one is called Snapseed (free in the App Store). I’ve been using this app since I started using Instagram. The Selective Adjust tool is fantastic! It lets you fine-tune certain parts of the photo. I really recommend this app to anyone. It has a lot of tools and is very easy to use. The second one is VSCO Cam (free in the App Store). I usually only use this app to add a filter to my photo after doing all my fine-tuning in Snapseed. I normally don’t like to go overboard with the filters. I use them halfway, and that’s it. My favorite filters are the A, C, N, S, and B filters.

This post was originally published at Travel Break and is reprinted here with permission.

12 people who kept me traveling

Photo: Luke Montague

1. The Lisboeta girl who was waiting for the Skopje flight at Zagreb Airport

I kept watching her with curiosity while she tried different seats in the waiting room. When finally she sat next to me, I wondered if I should talk to her or not. Something about her told me she was a local, and I assumed she was going home to Skopje, Macedonia. She was a short and good-looking girl with black hair, green eyes, and cool jeans. She reminded me of a good friend I had in Catalonia, and I decided to at least say hello.

After sharing a few words, I was already in love with her smile, and I discovered that she was from Lisbon, Portugal. She told me she was going to stay in Skopje for five months, which made me feel less lonely and a little happier. Once we arrived at Skopje Airport, it was time to say goodbye but only after she gave me her email. Smooth.

2. The local taxi driver who told me some things about the Balkans

“We were too powerful, you know. When we all were the former Yugoslavia, we had everything. We loved it, being all the Balkans countries together. But power sometimes brings problems. So stronger nations than us began to whisper, and that was everything. And now here we are, Macedonia and the rest, just a bunch of small powerless countries easy to control.”

3. The lovely reggae-style Macedonian girl who worked afternoon shifts at the coolest hostel in Skopje

She studied Anthropology at Skopje University, and she had just started working in the newest, biggest, coolest hostel in town, the Lounge Hostel. It was a cozy place for real travelers just near City Park and the Vardar River. It was a sunny day in the middle of August.

She took me on a walk around the city and showed me some genuine local spots that ‘Lonely Planet’ tourists would have no idea about. We ate lahmacun and ayran in a hidden place called Gallery 7 in the Old Bazaar for 120 denars each. She told me that there was a Picasso I should see in the Contemporary Art Museum. And we finished the afternoon gazing at the Skopje sunset from the Kale Fortress while drinking Macedonian Skopsko beers.

4. The Malaysian workawayer who was traveling around Europe and wanted to try paragliding in Kruševo

He lived in Singapore for seven years before he decided to travel a bit around Europe. He had already visited London, Munich, Ljubljana, Belgrade, Pristine, and Ohrid. By the time I met him, he had been living in Skopje for more than a month working as a volunteer in a hostel.

When we met for the first time, he was cooking some pasta with tomatoes, tuna, and white cheese. “I’m just learning how to cook, man,” he told me. “In Malaysia, I buy everything to eat in the streets. It’s cheaper than cooking.” The next day, he told me he was going to try paragliding in Krusevo. “You in?” he asked. I didn’t have to think about it much: “Damn! Paragliding eh? Sure.”

5. The vegetarian blonde girl from Antwerp who lived with two cats and loved Wittgenstein

She already had a degree in philosophy and next year would begin studying literature. I was reading The Old Man and the Sea the first time I saw her. The next morning we shared breakfast at the hostel and I offered her an unsuccessful Turkish coffee. We both visited Matka Canyon, and traveled almost one hour by boat to see a wonderful cave full of bats. In the afternoon we had a few beers at Bistro London in downtown Skopje. A day later she traveled to Kosovo. I quickly forgot the names of her two cats but I ate a delicious sandwich with the Gouda cheese she left in the hostel’s communal fridge.

6. The traveler woman from the Netherlands who wanted to improve her Spanish before going to South America

She took a year off from her white-collar job just to travel. She had spent the past three months teaching English in Cambodia. We met when she was traveling around the Balkans. After a month at home in Rotterdam, she would go to South America to search for some new experiences.

I met her while looking for travelers in Skopje on Couchsurfing; we went for a coffee. She was talkative and funny and interesting. And before saying hasta la vista y buen viaje to each other, she told me to check out the Workaway opportunities in the Netherlands. I did and saw “Looking for a native Spanish speaker to help me to improve my Spanish in Rotterdam.” Rotterdam, eh?. That sounded cool enough.

7. The Albanian waiter who served me a really good 20-denar blackberry juice

It was my first time walking alone around the Old Bazaar of Skopje. I felt everyone was staring at me. All the locals were probably thinking, “Look at the tourist.” My Spanish-looking face, and my yellow flashy t-shirt fingered me easily among all the Macedonian, Albanian, and Turkish locals who were wandering around. But then I went down a tiny street and I saw this cool coffee-tea place where I instantly knew I would feel at home — in the middle of that strange neighborhood with so many cultures wonderfully mixed. The waiter came, smiled, and offered me a blackberry juice. “It’s delicious,” I told him. And I ordered one more, and another, and another…

8, 9, 10, and 11. The four young girls who were interrailing Europe for three weeks, and couldn’t hold their rakia

They were from Barcelona. And their plan was to visit Athens, Thessaloniki, Skopje, Belgrade, Zagreb, Florence, Torino, Marseille, and Tolouse. They had just arrived to Skopje, and the hostel owner was telling them where to find the best restaurants and about traditional Macedonian drinks. “Skopsko is the most popular beer, Stobi is a really good wine, and rakia is, well, you definitely should try rakia before you leave. You can buy Lozova Rakija in the supermarket.” They said happily that they would. Then I asked them if they had drunk whiskey before, and they said no. Ufff, it’s going to be painfully funny then, I thought and laughed.

12. The Turkish hotel chef who taught me how to play backgammon

I met this Turkish guy who was killing everyone playing backgammon. After all the matches I asked him to teach me some tricks. I learned about the game, and also discovered that he was a professional cook working in a hotel in Anatolia. “Come to Turkey, man. You’ll love it,” he said. On his last night at the hostel, he cooked a typical Balkans dinner with pickles, cheese, yogurt, hummus, watermelon, parsley, eggplant, onion, yellow and red peppers, garlic, lettuce, and a fantastic pink fish cream with a very complicated Macedonian name. It was awesome.

How to walk across Europe

Photo: Bill Bereza

Start by standing at the Hook of Holland with your back to the North Sea, facing uncertainly inland. Allow yourself several minutes of intense reluctance to begin. Realise you can’t do that all morning, and you may as well stretch your legs. Put one foot in front of the other. Repeat. Repeat again. Keep going vaguely southeast for the next eight months.

Don’t think about your destination. It’s 2,500 miles away, the other side of seven borders and three mountain ranges. You have walked 20 miles so far. So don’t think about it.

Don’t rush. This sounds obvious, but the obsession with travelling fast is ingrained in our culture. Travelling slowly is not just something you do with you body, but with your mind. Understand that this might take you several weeks to learn.

Don’t resent the bicycles that pass you on the smooth Dutch roads. Don’t even think of resenting the cars. Don’t resent anything that moves faster than you.

Ignore the pain on the second day, when it begins to explore your feet. Ignore the pain on the third day, when it gains confidence in your shins. Ignore the pain on the fourth day, until you realise you can hardly walk. Find shelter. Rest and recover, curse yourself for being a fool, wait until the pain has gone. Continue.

Cross your first national border, which is more of a psychological border. Find the graceful River Rhine and keep it on your left. Practice the German for ‘on foot’ — zu Fuß. Walk upstream, against the current, into the heart of Europe.

Learn strategic routes through the landscape. Avoid hard-impact surfaces. Grass, leaf mulch, flowerbeds, and lawns are preferable to tarmac.

Be flexible with trespass laws. The land is not designed for your passage. A walker today is a rebel in an autocracy of cars.

Be flexible with vagrancy laws. This is not homelessness — you have homes everywhere. Learn to sleep in secluded woodlands, ruined castles on the Rhine, abandoned hunting hides.

Accept what strangers offer you: beds, sofas, cigarettes, hot meals, directions, stories. Entertain the hypothesis that your presence is not a burden. People take delight in being kind — aim not to disappoint them.

Acclimatise to gradual change. The world is different with every step. Shifts in landscape, dialect, beer are the true milestones of your journey.

In Bavaria, learn to walk in snow. It’s like learning to walk all over again, one step forward and a half-step back, sometimes plunging up to your knees. Accept that your snot will form icicles, and your beard will freeze.

Cross your second national border. Buy a warmer pair of gloves. Do not attempt to cross the Alps. Keep the Danube to your left, and follow the ice downriver.

Understand only then, after eight months of walking, that your journey was never a means to an end but an end in itself. Every person that you met — every stone and tree, every stream and hill — was your true point of destination.

Rest a week in Vienna. Fatten up on strudel.

Cross your third national border. Be prepared for culture shock. The language is different, the colours are different, the faces are different, the smells are different. Practice the Slovak for ‘on foot’ — pešo. Say goodbye to the winter.

Beware the dogs of Slovakia. Understand that the further east you go, the people get nicer and the dogs get nastier. Carry a stick in your hand, stones in your pocket.

Upon arrival in a village, locate the nearest bar. Endure initial baffled stares. Order beer. Wait. Within ten minutes a drunken farmer will be buying you pálinka, clasping your hand, roaring in your ear. You will have crossed a symbolic threshold. Do not underestimate the ritual power of this.

Cross your fourth national border. Forget all you learned of Slovak. Practice the Magyar for ‘on foot’ — gyalog. Walk east from Budapest.

Teach yourself to be aware of a different order of fascinations. Scraps of rubbish, centipedes, the patterns dust makes under your boots. Become adept at identifying roadkill: foxes, deer, polecats, cats, exactly half a dog.

On the Great Hungarian Plain, accept that your clothes will never look clean. Accept that you will sweat constantly. Accept that your beard will grow unruly. Accept that, by conventional standards, you will smell pretty bad.

See nothing but flatness for one day. See nothing but flatness for two days. See nothing but flatness for three days. See nothing but flatness for four days. See nothing but flatness for five days. See nothing but flatness for six days. See nothing but flatness for seven days. See nothing but flatness for eight days. On the ninth day, see hills.

Cross your fifth national border. Watch the land turn from yellow to green. Practice the Romanian for ‘on foot’ — pe jos. Eat a lot of sheep’s cheese.

Sense a shift in attitude — you feel more welcome in this land. Be prepared for everyday acts of courtesy, humour and hospitality. Wonder whether the change has happened in the culture, or in yourself.

Acclimatise yourself to new differences. Learn to read the subtle signs that indicate that you have entered a Romanian, Hungarian, Szekler, or Roma community. Absorb the prejudices of each as you do the seasons or the cooking.

Develop a series of minor eccentric and unsavoury habits. Talk to the landscape as if it’s a person. Talk to yourself, and then tell yourself (out loud) that you shouldn’t talk to yourself. Feel okay with that.

Learn to walk in hills again. Learn to walk in rain again. Learn to treat Transylvanian sheepdogs with the respect you might otherwise reserve for demigods or demons.

Cross your first mountain range. See no other person for three days. Discover wolf tracks in the snow. Realise, on top of the highest peak, that you could easily die.

Walk for one day in the fog. Walk for three days in the snow. Walk for five days in the rain. Find yourself on the point of forgetting what it’s like to be dry.

Cross your sixth national border. Follow the Danube once again. Practice the Bulgarian for ‘on foot’ — пешa. Practice a whole new alphabet.

Acclimatise yourself to new differences. Learn to read the subtle signs that indicate that you have entered an eastern, southern, Balkan, Slavic, ex-Ottoman, ex-Soviet sphere. Know that history happened yesterday here. Or it never stopped happening.

Cross your second mountain range. Cross your third mountain range. They are the same mountain range (your road is hardly straight).

On the Black Sea coast, learn to walk on sand. It’s like learning to walk all over again, one step forward and a half-step back. Discover that it’s easier to walk barefoot, on the hard sand of the tideline, your broken boots swinging from their laces round your neck.

Discover the pleasure of being clean. Stop to swim more frequently than you stop to eat.

Keep the Black Sea on your left. Walk south. You can’t get lost now.

Cross your seventh national border. There are no more borders left. Practice the Turkish for ‘on foot’ — yürüyerek. After weeks of sausage and bread, discover the joys of Turkish cooking.

Don’t think about your destination. You have walked 2,500 miles, over seven borders and three mountain ranges. Your destination is 20 miles away. So don’t think about it.

Upon arrival in a village, locate the nearest tea-shop. Endure initial baffled stares. Order tea. Wait. Within ten minutes a man will be buying you çay, clasping your hand, telling you these words: “For us it is a great honour you are here. The way we see it, you have walked all this way just to meet us.” Understand only then, after eight months of walking, that your journey was never a means to an end but an end in itself. Every person that you met — every stone and tree, every stream and hill — was your true point of destination.

Arrive in Istanbul with your eyes: first sight of skyscrapers.

Arrive in Istanbul with your feet: the outermost edgelands of the city.

Arrive in Istanbul with your mind: the glittering water of the Bosphorus, the end of Europe and the start of Asia, the point at which you can literally walk no further.

Be prepared for the paradoxical disappointment of arrival. Happiness will come to you later, but all you will feel now is sorrow.

Buy a mackerel sandwich on Galata Bridge. Sit quietly by the water. Close your eyes and listen to the seagulls, the song of the mosques. Don’t think about going home, not yet. For now, just hold that moment.

Nick Hunt is the author of Walking the Woods and the Water: In Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Footsteps from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul, to be published by Nicholas Brealey in Fall 2014, on sale October 28th.

11 comments Irish people hate

Photo: David

1. Do you guys celebrate St. Patty’s Day in Ireland?

Oh, Lord, where to start? First off, we do celebrate St. Patrick’s Day in Ireland, albeit a little different to the big cities of the world. Secondly, this isn’t a holiday celebrating one of Marge Simpson’s hideous sisters, so if you are going to shorten the man’s name, at least do it right by spelling it correctly as “Paddy.” New York may have commercial floats and well-drilled police bands, but Ballinamore has Tom, the 76-year-old farmer who has driven the same three-wheeled tractor down High Street at 3 mph for the past 40 years.

Also, feck off with the pinching!

2. So, what’s the deal with Protestants and Catholics now?

Both died out after the Online Atheist Uprising of 2012. At least I can only imagine so, as atheists seem to be the only people in Irish society under 40 who actually give a toss about preaching their beliefs incessantly. It’s been so long since religion has been an issue that I can’t even remember if it’s Rangers or Celtic I’m supposed to hate.

3. OMG, do you know [insert famous Irish celebrity here]?

Chances are, I know them just as well as you know Brad Pitt, Iggy Azalea, or whatever celebrity comes from your country. Ireland’s population isn’t located entirely within a 10-minute radius.

4. So do you guys still hate the English?

No!

Generations of Irish have found a second home in England and have been welcomed with open arms. Yes, we have had our differences in the past and no one forgets the sacrifices those that fought for our country made to grant us independence and eventual peace. International opinion of our current relationship is akin to that of U2’s career; not many seem to mention the good stuff after the 1980s. The truth is, we have as much in common as an iPhone and low battery life; we get along just fine!

Except when it comes to sport…

5. Do you know how to Irish dance?

If by Irish dance you mean fist pump to Avicii while managing not to spill my pint, then yes! A Lord of the Dance, 99% of the population are not. You’ve watched one too many terrible American-made movies where Michael Flatley seems to have taught us The River Dance, instead of covering the basics of English grammar! However, if you are lucky enough to bump into someone who genuinely does know Irish dancing, then you are in for a treat. These dancers have spent years honing their craft and can put on an incredibly energetic show. In contrast, most of us will just down enough pints to give us some liquid courage on the dance floor!

6. Oh yeah, I’m actually [insert miniscule fraction here] Irish.

A favourite of mine to hear. Once you go into anything beyond ¼, you’re straight into “not-give-a-shite” territory.

7. I hear it rains all the time.

Well, it does rain a lot, maybe not all the time, but pretty damn close! The weather is a major topic of conversation in Irish society. Pessimism is the dominant tone of all weather-related discussion with rain being the unheralded champion of all that is wrong with your day. Do you know what you can do with year-round rain? Fuck all!

8. You guys love to drink, right?

Cheers for another stereotype you cheeseburger-eating, gun-slinging American, pizza-making greaseball Italiano, etc.

9. We started at Temple Bar, drove right across to the Cliffs of Moher and then did the ring of Kerry.

I bank on hearing this phrase from any North American tourist who has visited beforehand. It probably wasn’t as close as the movie P.S. I Love You or Leap Year made it out to be, but, fantastic, you’ve driven on some horrid back-arse roads at some point and paid for an overpriced pint in the process. Yep, you were definitely in Ireland!

10. I love your accent.

It doesn’t seem to matter what corner of the country you come from, foreign folks love to hear us talk. You’ve now got a license to say whatever you want, and somehow sound attractive saying it! You may want to tone down the depth of your “tick midlinds vice” slightly and expand your vocabulary beyond “Jaysus” and “ah yea” for a few moments, as you attempt to converse with someone on a topic outside your comfort zone of Gaelic Games and Father Ted.

11. I’ve never been, but I’ve always wanted to go.

For such a small Island, we garner an incredible amount of goodwill from other nationalities. Most visitors to our shores leave with fond memories, an appreciation of our unique culture, and a never-ending desire to return to a land where the craic is had. However, I find one of the biggest compliments paid to Ireland comes from those who have yet to visit. Around the world, Ireland is regarded as a destination one has to visit at least once in their lifetime. So, what are you waiting for? Book the trip of a lifetime to the Emerald Isle, just don’t forget to pack a rain coat!

33 incredible images of Oakland

OVER THE LAST FEW MONTHS, Matador has published articles, photography, and video that show exactly what makes Oakland great. We’ve looked at the remarkable ethnic and cultural diversity of the East Bay; we’ve charted a week in the nightlife of the city; we’ve showcased the one-of-a-kind art and architecture on display; we’ve even mapped 30 incredible places located less than a four-hour drive from Oakland.

In the process, we’ve come across countless images that do a wonderful job of depicting the spirit of the city, and which have stayed in our minds for their beauty and inspiration. Here are 33 of our favorite.

1

The Bay Area

Looking west from the Oakland Hills, you can see the entire city spilling out before you, touching the waters of San Francisco Bay, and then gaze on to the coast. This image also illustrates how cloud cover and fog typically remain on the other side of the bay.

Photo: Franklin Hunting

2

Sunset jogger

A different view down to the bay, captured during a sunset jog. There's so much potential to get outside and active in and around Oakland.

Photo: Brook Anderson, courtesy of Visit Oakland

3

Tulips

Tulips are among the many varieties of flowers that grow well in Oakland's temperate climate.

Photo: Tom Holub, courtesy of Visit Oakland

Read more: 20 things you didn't know about Oakland

4

This is Oakland too

While Oakland is part of one of the largest metropolitan areas in the country, it also sits on the doorstep of some incredible natural areas. Head to the Oakland Hills and look east, and this is what you'll see.

Photo: Gary Pope, courtesy of Visit Oakland

5

Oakland style

This stunning portrait was capture at Art Murmur, Oakland's monthly art walk. Find out why everyone cool and creative is moving to Oakland.

Photo: Amir Aziz

6

Lake Merritt

Technically a tidal lagoon, Lake Merritt defines the downtown landscape of Oakland, covering 150 acres in the city center and ringed with parkland, paths, and residential neighborhoods.

Photo: Yoo Seung Ho, courtesy of Visit Oakland

7

Oakland Rotunda

Built in 1914 to house Kahn's Department Store, the Rotunda Building is now an upscale event space and sought-after wedding venue in downtown Oakland. The centerpiece of the structure, the dome, is 120 feet high and measures 5,000 square feet.

Photo: Brooke Anderson

8

Art and Soul Festival

Performers with the troupe Bandaloop dangle and dance from the face of Oakland City Hall during the 2014 Art+Soul Festival.

Photo: Greg Linhares, Omni Source Images

9

Street fair

The night's entertainment at one of Oakland's many street fairs.

Photo: Marlo Lao, courtesy of Visit Oakland

Read more: 11 underground spots in Oakland to check out before they go mainstream

10

Thai fusion

This dish of grilled paratha with tomatoes, eggplant, bell pepper, fresh basil, and green curry was served up at Soi 4 Bangkok Eatery on College Ave.

Photo: Sonny Abesamis

11

Lake Merritt gondolier

You'll see all manner of watercraft on Lake Merritt—sailboats, kayaks, pontoons, paddleboats, dragon boats, and even gondolas.

Photo: Ross Cameron, courtesy of Visit Oakland

12

Hiking in Oakland's backyard

A sea of gold and green provides a perfect escape from the city in the Oakland Hills.

Photo: Jerry Ting, courtesy of Visit Oakland

13

Nighttime reflections

At night, the still water of Lake Merritt casts reflections of the Lakeside Dr / Harrison St skyline, including the Cathedral of Christ the Light (visible at right).

Photo: Natausha Greenblott, courtesy of Visit Oakland

14

New Style Motherlode

At dance studio New Style Motherlode, you can sign up for dance and fitness classes for the whole family.

Photo: Zennie Abraham

15

Fox Theater

Oakland's Fox Theater opened in the late '20s and is still going strong, now hosting big-name music acts from around the world.

Photo: Tom Tomkinson, courtesy of Visit Oakland

Watch the video: This is what makes Oakland great

16

Oakland Marathon

The Oakland Running Festival, which features a marathon in addition to other running events, takes place in the spring and is considered one of the country's top races.

Photo: Ken Katz, courtesy of Visit Oakland

17

On the half shell

Oakland's West Coast location and active port give it access to incredible food from all over the world—not the least of which is fresh seafood. Grab a plate of gourmet oysters at Luka's Taproom on Broadway.

Photo: Visit Oakland

18

Oakland A's

Hometown sports pride, brought to you by the fan base that invented the Wave and fantasy football.

Photo: Nicole Abalde

19

On the ferry

Public transportation in the Bay Area comes in many forms—sometimes, the quickest way to get where you're going involves a ride on the ferry.

Photo: Mariam Marie

20

The new Bay Bridge

Construction of the attractive self-anchored suspension bridge (lit above) was completed last year, and it now serves as the eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, connecting Oakland to Yerba Buena Island. Among the span's many attributes (including being considered the widest bridge in the world) is that, for the first time, it provides access to pedestrians and cyclists to traverse the bay.

Photo: Darrell Sano, courtesy of Visit Oakland

21

Street food

Be it at a market, food truck, or street fair, grab-and-go (and delicious) street food is all over town.

Photo: Phillip Yip, courtesy of Visit Oakland

22

Mormon temple

The Oakland California Temple was one of the earliest operating temples of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, built in 1964. It's located in the Oakland Hills with great views of the city and bay.

Photo: Alma 7:12 (sticker trading)

23

Oakland sunshine

Challenging the stereotype of a foggy Bay Area, Oakland sees an average of 265 days of sunshine a year.

Photo: George Kelly

24

Art galleries

The art scene in Oakland is strong and growing stronger, with museums, studios, and dozens of high-profile galleries. Pictured above is curator Svea Lin Soll at Swarm Gallery in Jack London Square.

Photo: SWARM GALLERY OAKLAND

25

Oakland produce

Fresh produce isn't hard to come by anywhere in California, and Oakland is no exception. Hit up the farmers markets in Jack London Square, Grand Lake, Old Oakland, Temescal, Montclair, and elsewhere.

Photo: Lisa Ellis, courtesy of Visit Oakland

26

Fox Theater in action

TV on the Radio plays the Fox Theater in Uptown Oakland.

Photo: Josh Sanseri, courtesy of Visit Oakland

27

Mountain View Cemetery

Mountain View is more than a cemetery. Its location in the hills above Oakland makes it a popular picnic spot.

Photo: Sonny Abesamis

28

Redwood Regional Park

You don't have to head west or north from Oakland to see the world's tallest trees. Redwood Regional Park is just a few minutes' drive east of town.

Photo: Miguel Vieira

29

Sunset over the cranes

The Port of Oakland is an active container ship facility, visible for miles around thanks to its iconic cranes standing like sentinels on the shore.

Photo: Visit Oakland

30

Ozumo

You can find so many cuisines in Oakland it would be a challenge to try them all. Uptown's Ozumo is a recommended spot for Japanese.

Photo: Ozumo, courtesy of Visit Oakland

31

Industry and recreation

View from the walking trail at Middle Harbor Shoreline Park.

Photo: Ken Katz, courtesy of Visit Oakland

32

Golden State in the paint

Golden State Warrior small forward Harrison Barnes gets way up for a dunk against the Minnesota Timberwolves. The Warriors are one of Oakland's three major-league sports teams, and proof of why this town is one of America's premier sports cities.

Photo: Visit Oakland

33

On the waterfront

Views don't come much better than this.

Photo: Darryl McElroy, courtesy of Visit Oakland

This post is proudly produced in partnership with our friends at Visit Oakland. Find us on social and use the hashtag #oaklandloveit to share your Oakland story.

October 6, 2014

12 dates Russians go on

Photo: Henning Welslau

1. Just hanging out in your bedroom

There’s no word for “privacy” in the Russian language, and you embody this fact by remaining at home with your parents. As a result, any intimate activities occur within earshot of other family members. There’s almost always some kind of wall dividing your activities from babulya’s sausage platter — but there might not be a door.

2. Fine dining at McDonald’s

You’ll hover above occupied tables like a vulture in order to secure a seat while your date waits 20 minutes in line for a “Cheeseburger Royal.” And then the date ends at the McCafe for a mediocre cappuccino. It doesn’t matter that the first Russian McDonald’s opened in 1990, the chain remains an impossibly trendy hangout for you and your teenage/twentysomething friends.

3. Or Pizza Hut

Although your palate might have become increasingly multicultural, being raised on borscht and buckwheat makes you less adventurous in trying international cuisines — except where pizza’s involved. Much like McDonald’s, Pizza Hut is a place you consider to be a classy joint, offering the best pies one could hope to find in a Slavic shopping mall. Using a knife and fork is the only way to ensure you get a second date (eating with your hands goes against the way your parents raised you).

4. Shrooms with grandpa

In the month of September, you’ll gather wild mushrooms at your family’s dacha, or summer cottage. There you’ll undoubtedly meet your partner’s grandparents, who wile away their days gardening, foraging, and preserving food for winter. While granny’s in the kitchen canning huckleberries, you venture into the woods with grandpa and your lover to pick some delicious wild mushrooms. Just hope the old man’s eyesight is in check, otherwise you’re in for another trip entirely.

5. Tipsy picnics

The date begins with a long taxi-van ride to the middle of nowhere followed by the traversal of a few “Do Not Enter” signs, which are more like suggestions, really. Next, gather kindling for a bonfire upon which you’ll grill shashlyk (shish kebabs) and warm yourself as the woefully brief Russian summer is extinguished before your eyes. You’ve become an expert at peeing in the woods, mastering the stance after your fourth can of “Sex on the Beach.”

6. Structurally unsound sporting equipment rental

Even if you can’t get out of town, there are numerous parks within city limits where you rent sporting gear such as bicycles and rollerblades. You’re not really surprised to find that your bike is missing its brakes. And, no, you will not be given a discount.

More like this: 10 signs your boyfriend is Russian

7. Experiencing St. Petersburg’s “White Nights” after you’ve missed the last train

Depending on your luck, you may also be marooned on Vasilyevsky Island after all of the drawbridges connecting it to the rest of the city have been raised between 1:30 and 5am. But in spite of these inconveniences, you’re happy because it’s June and you’re stumbling through one of the world’s most beautiful cities with your new paramour. At 5:30am, you’ll catch the first metro train of the morning along with dozens of other bleary-eyed souls.

8. A lot of walking, in general

The Russian verb for “to go out” (pogulyat’) literally translates into English as “to take a walk.” This linguistic nuance, combined with the sprawling Stalinist avenues lining most Russian cities, ensures that on any given date you’ll walk no fewer than two miles. And it’s not unusual for the entire evening to consist of one long walk punctuated only by purchases of ice cream and beer.

9. Death-defying drives

Safety is usually compromised anytime you’re lucky enough to date someone with a car. You’re privy to all of the neighborhood’s potholes and traffic cops, as well as which sidewalks make the best parking spaces. And riding in the passenger seat exposes you to the perils of the Russian road; Saturday evenings involve watching car accidents occur every couple of miles or so.

10. Culture, up close and personal

You boast about your encyclopedic knowledge of the nation’s art and history, making you a fantastic tour guide for visits to the Hermitage, Tretyakov Gallery, or any other one of the country’s superb museums. Whisper sweet nothings about Malevich’s Black Square into your partner’s ear as you huddle in front of the stark painting. Who knew Modernism could be so romantic?

11. Ice skating in polar vortices

A temperature of -25 °C isn’t enough to hinder outdoor plans. It is enough, however, to give you frostnip, a precursor to frostbite — even through clothing. So before setting foot on that suburban pond, you don every single item of clothing you own. And you undoubtedly understand that mittens are warmer than gloves.

12. Savoring the simple things

Sometimes there’s nothing better than buying a freshly plucked chicken and some scruffy veggies from the local bazar. These basic ingredients, even when cooked atop your crusty dormitory hotplate or minuscule stove, can yield the finest meal. Intimate, unrefined, and a little bit greasy, these are the most satisfying dates of all.

Meet the surfer inspiring Baja kids

Follow Matador on Vimeo

Follow Matador on YouTube

LA MAESTRA (The Teacher) is a half-hour documentary about a young Mexican woman who decides to follow her own path and in doing so, inspires other to do the same and changes her community’s expectations of what’s appropriate for girls and women. The film profiles Mayra Agulair, a teacher in a tiny rural fishing village in Baja, Mexico, who becomes the first Mexican woman surfer in her area.

Told in Spanish with English subtitles using mainly Mayra’s voice, the film shows how she has gone on to inspire both her students and other local women to take up the sport and follow their dreams. Through her deep connection to the ocean, Mayra has also become an environmentalist, teaching her students the importance of land and sea stewardship through hands on learning.

Check out La Maestra’s Indiegogo page here, and help make this film possible.

Here’s what you really need to know about Ebola (in 4 minutes)

Follow Matador on Vimeo

Follow Matador on YouTube

EBOLA IS NO JOKE — and I think it’s fair to say that even the most laid-back of self-healer types are seriously freaked out about it (especially now that some infected travelers are returning to the United States). We can help prevent the spread of this virus through education however. Learning about what causes Ebola, and how to avoid it, as well as what efforts are being taken around the world to contain it, are all things we need to know in order to reduce panic, and raise awareness. This video, compiled by YouTube Nation, provides some quick insight on this global health issue, and shares ways we can help combat the virus from afar.

7 moments to embrace being a tourist

Photo: televiseus

I’m so over the whole traveler vs. tourist debate. By definition, a traveler is “someone who is traveling or who travels often,” and a tourist is “a person who travels to a place for pleasure.” Both of those sound nice to me, but if you’d like to expand on those terms, give Merriam-Webster a call.

Every traveler has done something “touristy” in their lifetime, so maybe we can all quit ragging on the term. Besides, there are plenty of times when I’m not at all ashamed of being a tourist.

1. When you’ve been dying to see / eat / buy something.

When I’m in Brussels, I’m going to have chocolate. And I’m not going to pass up a chance to visit Machu Picchu just because it’s the #1 attraction in Peru. We travel for a reason, and these reasons are usually inspired by things we’ve read about, seen photos of, or have watched on television.

So if you’ve always wanted to go on a gondola ride in Venice because you equated it with this idea of romance, even though some hardcore “traveler” said they wouldn’t be caught dead doing so, fuck it. You’re doing yourself a disservice if you limit your travel experiences based on what other people deem overrated.

2. When it will help impact the community in a positive way.

Kente cloth is expensive, and usually saved for special ceremonies in Ghana, so buying it is a pretty touristy thing to do. But my Ghanaian friend’s uncle was a kente weaver, and he created beautiful, custom fabrics for my friends and me. We later went to the Arts Centre Market of Accra, where they had cheaper, factory-made kente cloth. My friends felt ripped off, but I felt good knowing all of the profits had gone back to Addae’s family directly (and that the fabric was actually made in Ghana, not imported from China).

If the attraction has a positive impact on the environment and community where you’re traveling, don’t worry about being a tourist.

3. When it will educate you.

Auschwitz comes to mind. I don’t think many people would call a concentration camp “overrated” and “touristy,” no matter how crowded it feels, how expensive the entry ticket may be, or how quickly the tour guides zip you through the grounds.

Museums, heritage sites, and guided tours are all ways to experience the history and culture of a place that you won’t necessarily get by sitting in a coffee shop and “people watching.” You could read a book about it, but listening to someone talk about how Stirling Castle was built, and seeing the structure and the artifacts themselves, is much more interesting.

4. When it’s something you enjoy, wherever you are.

I’m a zipline fanatic. If I could set up a zipline in my backyard, I would. So when I hear there’s a place to zipline in whatever city I’m stationed in, I do it. Ziplining isn’t “authentic” to any culture really, and you won’t find any locals partaking in the adrenaline rush beyond the folks who work there. But ziplining through Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains was different than ziplining through the rainforest in Costa Rica, and very different from the ropes course I explored in western Connecticut.

It’s important to choose these activities responsibly, though — everybody likes having sex, but if the only way you can get some action is by contributing to the local sex-traffic ring, you probably need to reevaluate the reason you’re traveling to begin with.

5. When your curiosity is piqued.

If I want to know what McDonald’s tastes like in a foreign country, I don’t give a crap how “touristy” I look while devouring Le Big Mac in France. If something makes you wonder, “What if?” just go for it.

“What if I meet the man of my dreams at the top of the Empire State Building?” “What if I snap an awesome photo of the Prague Castle from a cruise on the Vltava River?” “What will happen if I drop some extra change into the guitar case of this street busker in Buenos Aires?” Some of the most exciting and fun experiences I’ve had abroad came from going through these exact motions.

6. When the locals are cool with it too.

The Nathan’s hot dog stand at Coney Island is not the only place to get hot meat on the boardwalk, but I stand in the long line in the broiling sun with travelers from around the world because Nathan’s hot dogs are the bomb. If you’re in Rio for Carnival, you’re definitely doing something touristy. It’s okay, because there are people coming from other parts of Brazil to experience it as well.

7. When you have a hunch you won’t be back.

There are definitely countries I have no desire to visit again. It doesn’t mean I had a horrible experience, or that “I’m over it,” but there are other places I’d rather see before deciding to return.

Costa Rica is one of them. It’s a beautiful country and I had a great time, but I want to check out Panama, Nicaragua, and some other neighboring countries before heading back. So I did the rainforest tours, and the canopy walks, took surfing lessons and cooking lessons at Coco Beach, knowing I wouldn’t get to do it again for quite some time.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers