Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 37

May 7, 2017

Mourning in the 1880s: U.S. vs Great Britain

Sargent, Mrs. Adrian Iselin 1888

Loretta reports:

Sargent, Mrs. Adrian Iselin 1888

Loretta reports:Having recently viewed the famous widow-dancing scene in Gone with the Wind, and encountered a late Victorian widow in a novel, I wondered how different mourning rituals were in the U.S. and Great Britain.

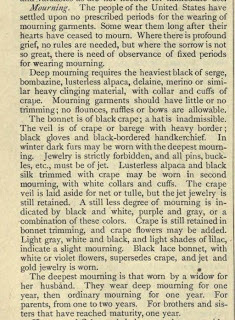

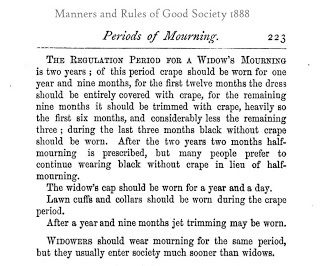

Obviously, things changed from Scarlett O’Hara’s time. The clipping from American Encyclopedia of Practical Knowledge 1886 tells us there aren’t any hard and fast rules, while the one from Manners and Rules of Good Society (England 1888) is quite specific. My own copy of Manners and Rules of Good Society for 1911 shows a loosening of the late Victorian rules, but things still aren’t as casual as in the U.S., and one can imagine some of the older generation frowning at younger widows who shorten their mourning period to less than 18 months.

U.S. Mourning 1886

U.S. Mourning 1886

England Mourning 1888

England Mourning 1888

Image: John Singer Sargent, Mrs. Adrian Iselin 1888, courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC, via Wikipedia.

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on May 07, 2017 21:30

May 6, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of May 1, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Two babies born in the Tower of London, two very different lives.

• The saga of the skull of the man who prosecuted Aaron Burr, defended the Cherokee Nation, and was the country's longest tenured attorney general.

• Elizabeth Bronte, more than a footnote.

• This book was the WebMD of the 18th and 19th centuries.

• Image: Photo of young marchers from a 1909 May Day parade to end child labor.

• Abigail Adams considered May 1 King Tammany's Day .

• A 1698 recipe whose popularity has probably passed: "To Pickell Larks ."

• The art of marbled paper from the archives of the San Francisco Public Library.

• When spirits and witches roam abroad: April 30, or Walpurgis Nigh t.

• A small metal alms box reveals Americans' thoughts about philanthropy .

• Image: Thomas Jefferson's "original Rough draught" of the Declaration of Independence .

• Evil May Day, 1517, and the immigrant rioters in Tudor London.

• The Traveller's Pocket Book provided an early glimpse of Great Britain's roads in the 18thc.

• The well-shod Edwardian woman .

• Hearts of oak on canvas: Copley's Watson and the Shark .

• Image: A gold compact by Cartier with the initials of silent screen star Mary Pickford.

• Costumed roosters and sphinx cakes: highlights from Victorian cookbooks .

• An entertaining quiz to determine who you would have been in the American Revolution.

• The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851.

• The other side of Anne of Green Gables : the danger of rewriting a beloved book for a new generation.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on May 06, 2017 14:00

May 4, 2017

Friday Video: London on my Mind

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:I’ve got London on my mind even more than usual because I’ll be heading there in a few weeks to spend the entire month of June in an orgy of visits to museums, theaters, historic sites, and other Nerdy History Girl irresistible temptations.

The film's narrator, Rex Harrison, like 1950s London, is with us no more. But the travelogue does capture the scope of the place, reminding me that a month will never be enough, and a lifetime probably wouldn’t be enough. I also chose this film because it spends a few minutes in Fleet Street, the Inns of Court, and a few other places that feature in Dukes Prefer Blondes.

Londoners and London lovers, please feel free to suggest places for me to visit. I’m still working on my itinerary.

This Is London Reel 1 And 2 (1950-1959) , courtesy British Pathé .

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on May 04, 2017 21:30

May 3, 2017

From the Archives: Everyday Clothing: A Rare Woman's Shortgown, c1780-1800

Susan reporting,

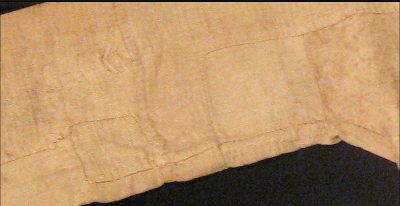

Susan reporting,This post originally appeared in connection with a 2014 exhibition at Pottsgrove Manor, the 1752 mansion of prosperous colonial ironmaster, merchant, and judge John Potts (c1710-1768) in Pottstown, PA. While the exhibition has long since closed, I've always remembered this well-worn shortgown - the kind of clothing worn by everyday women in 18thc America, and now extremely rare.

As promised, here's one of the 18th c. garments from Pottsgrove Manor's current exhibition, To the Manor Worn: Clothing the 18th Century Household, that I featured here . The exhibition included silk gowns, a magnificent embroidered waistcoat, silk breeches, and quilted silk petticoats.

The shortgown, above left, is considerably more humble, and because of that, it's much more rare, too. Like the 19th c. cotton dress I wrote about here, shortgowns were most commonly worn by working women, and they often turn up in the advertised descriptions of runaway indentured and enslaved servants. Shortgowns were t-shaped garments with a flared hem that were comfortable for physical labor. They had no fastenings, but closed with straight pins along the front opening. Made from cotton, linen, or wool, shortgowns were worn over a linen shift and a petticoat; they were early, easy separates.

An 18th c. working woman's wardrobe was limited, and each article received hard wear. Clothes were mended and refashioned until there was literally nothing left but rags, which in turn would then have had another life around the household. Unlike a wedding gown or baby cap, a shortgown like this would not be set aside and preserved for posterity. Even the few that have survived would not find a welcome in most modern costume collections, which tend to concentrate on the clothing of the elite classes, beautifully constructed clothing of rich fabrics.

This shortgown tells a different story. Its owner was neither wealthy nor famous, but she was thrifty and resourceful and skilled with a needle. The fabric is either corded linen or cotton, once off-white and now discolored with age. The simple style could have been made by the wearer herself.

As the exhibition catalogue notes, "In the 18th century, the material made up the biggest cost of a garment, so even the clothing of wealthy individuals often shows some level of patching to get as much use of the fabric as possible."

This shortgown has been patched, and patched again, with neatly squared patches and careful stitching. As you can see in the detail, right, some of the patches are scraps of the original fabric, and others are simply similar fabric. Most of the patches are in places that would have received the most stress and wear, under the arm and along the sleeves.

The name and history of the shortgown's owner are long forgotten, but she left her testimony in each of the tiny stitches across each frugal patch, making the most of what she had. She's as much a part of early American history as George Washington, and I'm glad to see her work preserved and presented as the treasure that it is.

Many thanks to Pottsgrove Manor's curator Amy Reis and the rest of the staff for their assistance with this post.

Above: Women's shortgown, linen or cotton, c.1780-1800. From the collection of the Chester County Historical Society. Photograph courtesy of Pottsgrove Manor.

Published on May 03, 2017 21:00

May 1, 2017

Fashions for May 1844

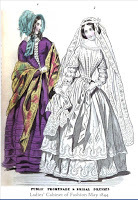

May 1844 Walking & Bridal Dresses

May 1844 Walking & Bridal Dresses

Loretta reports:

Last month, we looked at the wild and crazy fashions of the 1830s . Though they seem more graceful and flattering in paintings than in fashion prints , and not everybody loves the style, I think we can agree that they were not subdued.

Of the 1830s, Cunnington’s English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century has this to say: “The fashions of this decade illustrate the transformation from a phase exuberantly romantic into one droopingly sentimental. The change occurred abruptly in the middle of 1836.”

In this regard, Mr. Cunnington gets no argument from me. So far, all the fashion prints I’ve seen illustrate this transition.

May 1844 Visiting & Walking Dresses

May 1844 Visiting & Walking Dresses

This droopier, subdued look continues in the 1840s. According to Cunnington, “The Englishwoman of this decade cultivated her feelings at the expense of her body. She was less physically active than at any period in the century; she was absorbed in acquiring the art of expressing emotions by graceful attitudes rather than by movement. Her dress, therefore, was admirably designed for passive poses. …Sentimentalism in England finds a natural mode of expression in the Gothic, and it was the period when Victorian Gothic was at the height of its popularity.”

I wish I had been able to find, in the limited time I had, better quality fashion prints for the 1840s. However, you can see something closer to a portrait painting here and here , both of which illustrate the radical change in hair styles as well.

Dress description

Dress description

Dress description

Dress description

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on May 01, 2017 21:30

April 30, 2017

When an 18thc Tent Becomes a National Relic

Susan reporting,

The new Museum of the American Revolution is filled with fascinating artifacts from the past, objects that tell stories, represent people, explain ideas, or are examples of exquisite craftsmanship. (See my earlier posts here and here .) But among all these treasures, there's only one that's a true relic on a national scale: George Washington's Headquarters Tent.

Quite simply, it's the real deal. From 1778 until 1783, this large (it's about twenty-three feet long) tent served as home and office to the commander-in-chief. While various houses were employed as headquarters during the war's many campaigns, Washington believed in sharing the same hardships as his troops. To be sure, the general's tent was more substantial than that sheltering the average soldier. His tent was supported and shaped by numerous poles and lines, and contained three small chambers: a central office, a half-circle sleeping chamber, and another small area for his luggage, with sleeping quarters for his enslaved African American valet, William Lee. But the canvas walls were the same, as was the damp or frozen ground beneath his feet. If the men were sleeping in tents through downpours, bitter frosts, and blistering heat, then the General did, too, and they respected him all the more for it.

Washington met with his generals and staff inside this tent, and major decisions about the war and the country's future were settled within it. Here Washington would also have experienced his most private moments, and the emotions that, as commander-in-chief, he was required to keep to himself: his longing for his home and family, his fears before a battle, his joy after a victory tempered by his grief for the men he'd lost, even his doubts about the war itself. If ever a single place carries the spirit of General Washington, then it's this tent.

After the war, the tent was packed into storage at Washington's home of Mount Vernon, but its role as a symbol was only beginning. The tent was passed down through the 19thc to Martha Washington's great-granddaughter, Mary Anna Custis Lee, who was married to General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War. When the Lee house was captured by Union troops, the tent was sent to Washington, DC. There it was displayed to the public, marshaling all the patriotic fervor of Washington's memory.

After the war, the tent was eventually returned to the Lees, who sold it to raise money to benefit Confederate widows and orphans. The buyer was Rev. W. Herbert Burk, an Episcopal minister who was collecting objects related to the Revolution with the hope of one day displaying them in a museum. He raised the $5,000 to purchase the tent via contributions from ordinary Americans who shared his dream - a dream that nearly a hundred years later finally became the new museum that opened last month in Philadelphia.

But over the centuries, the tent had become a wispy shadow of itself. The canvas had deteriorated until it could no longer support its own weight, and a large piece had been cut from the side by another collector. Over five hundred hours of skilled conservation work by Virginia Whelan, the museum's textile conservator, has preserved the tent for another generation. The structural engineering firm of Keast & Hood created an elaborate interior aluminum and canvas sub-tent to support the fragile tent, and yet give the appearance of draped canvas. The elaborate structure of ropes and poles is now strictly for show. (This brief video shows the installation in progress.)

Still, the delicate fabric can only withstand very limited exposure to light and other environmental elements, and the tent is carefully maintained in a 300-square-foot, climate-controlled display case. Faced with these limitations, the museum's multi-media presentation of the tent is an engaging and emotional experience. Long-time readers of this blog will recall the replica of the tent and its accoutrements hand-made at Colonial Williamsburg ; that tent acted as a "stunt double" for the real tent in the accompanying film.

But it's Washington's headquarters tent that remains not only the star of the show, but of the museum. If you visit, be sure to attend the ten-minute presentation. At the end, when the tent is revealed, I guarantee you'll have a history-chills moment.

Photo courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution.

Published on April 30, 2017 19:05

April 29, 2017

Breakfast Links: Week of April 24, 2017

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Finally, from Italy, the full George Washington .

• Charles Dickens called this machine a monster - but it helped the lives of Londoners.

• The sad perils of love unapproved by Queen Elizabeth I: Lady Mary Grey .

• Coach-building in the late 18th-early 19thc.

• Preserving the signs of censorship in a 16thc astronomy book.

• Tiny hand-bound books made by the Brontes as children.

• Image: A stunning 1939 embroidered outfit by Schiaparelli .

• Florence Nightingale's "rubbish' amulets to go on display for the first time.

• Europe's famed bog bodies are finally beginning to reveal their secrets.

• Image: Women on a fire escape during a drill, c1913; their hobble skirts made it difficult to escape in the event of an emergency.

• Surgeon, apothecary, engineer, inventor, antiquarian, musician, artist, and author - William Close was all of these.

• While this menu from Delmonico's is interesting in its own right, the history of its ownership adds to its context.

• Romania's problem with Dracula .

• Drums, bugles, and bagpipes in the Seven Years' War.

• Pirate Sam Bellamy lacked the fame of Blackbeard, but made more of a fortune.

• Is it just a recipe for soup , or a counter-revolution in a bowl?

• Image: Daffodil from Grandville's Flowers Personified, New York, 1845.

• After the devastation of World War One, French women sustained their families by embroidery sold to Americans.

• Louise May Alcott wrote "The Brother" for The Atlantic based on her experiences as a Civel War nurse.

• A tiny face on a glass bead looks at you through a screen from the 1stc BC Roman Egypt.

• Fur coat worn by Titanic stewardess sold for £150,000.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on April 29, 2017 14:00

April 27, 2017

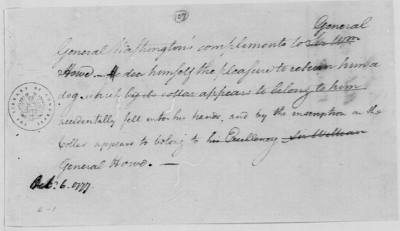

Friday Video: Two Gentlemen and a Lost Dog, 1777

Susan reporting,

Commercial advertising seldom veers into nerdy history, but a new advertisement from Pedigree dog food features a little-known historical incident involving two gentlemen, a lost dog, and the Revolutionary War. The advertisement is part of Pedigree's series with the tag line that "dogs bring out the best in us," and this advertisement proves exactly that.

I won't ruin the spot with spoilers, but what's shown really did happen. The draft of the note, below, now in the Library of Congress, was written to accompany the dog. The message is from the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, General George Washington, writing to the commander of the British Army, General William Howe. Washington was himself a great dog lover (there's an entire page on the Mount Vernon website devoted to his dogs), and did in fact return his enemy's lost pet, one gentleman to another. As was his practice, Washington dictated the note to a aide-de-camp. In this case, the aide was a young lieutenant colonel named Alexander Hamilton, who, despite his unquestionable devotion to the American cause, was still sufficiently dazzled by Howe's title that he first addressed him as "Sir William" instead of "General."

Of course, the advertisement doesn't *quite* get things historically correct. The Battle of Germantown took place on October 4, 1777; there was a heavy fog for most of the battle, and not a trace of snow. Washington was only forty-five at the time, not the craggy icon shown here. As for Colonel Hamilton - the real Hamilton in 1777 was barely out of his teens, a slender, fair-skinned, red-haired college drop-out.

Still, it's all a bit more plausible than this version of General Washington (I think it's the same actor, too) routing the British in a muscle car .

"General Howe's Dog", Pedigree, Agency: BBDO, New York, directed by Noam Murro.

If you receive this post via email, you may be seeing a black box or empty space where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on April 27, 2017 18:28

April 23, 2017

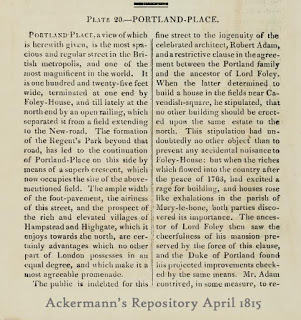

Portland Place in 1815

Portland Place 1815

Portland Place 1815

Portland Place description

Loretta reports:

Portland Place description

Loretta reports:Not until I read this entry about Portland Place did I know there was such a building as Foley House, or the rules that once existed about building in the vicinity. Not surprising. So many great London houses have disappeared, some with virtually no trace. However, I did manage to find an old engraving online (please scroll down), from Old and New London, one of my oft-consulted Victorian guidebooks to London’s history (complete, apparently, with various Victorian myths).

Portland Place is still an impressive street, though you will see more than a couple of carriage rattling around on it these days. And the road is paved, yes.

Portland Place description

Portland Place description

Images from Ackermann's Repository for April 1815, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, via Internet Archive.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on April 23, 2017 21:30

An Elegant Block-Printed Cotton Gown, c1805

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,This elegant - and adaptable - gown is on display in the Printed Fashions: Textiles for Clothing and Home exhibition (currently at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum of Colonial Williamsburg through 2018; see other articles from the exhibition I've mentioned here , here , and here ). The photo, right, shows the dress as it appears in the exhibition, and gives you an idea of just how much other printed gorgeousness is on parade in this amazing exhibition.

There are several features that make this dress unusual. First is the fabric itself, a block-printed cotton that was intended to mimic lapis, reflecting the era's interest in nature as inspiration for design. The fabric was printed with a curved hem border design (called "to form" or "a disposition") to be incorporated into the garment's finished design when made up. Also of interest is the fact that the dress has a pair of matching long sleeves or mitts to offer extra options to the wearer.

Here's the collection's placard:

"This small-scale spotted pattern was printed especially for a gown of this style. The red borders outlining the hem of the curved train and the skirt front are printed to the finished shape, not stitched on separately. The remaining red trimmings around the sleeves and neckline are cut from the printed yardage and stitched in place.

The red and blue printing technique is usually known as the "lapis style," named for the semiprecious stone with a blue ground. The printing method involved printing a mordant (color fixative) for red in with a resist paste before dyeing in indigo blue.

This graceful gown exemplifies the neoclassical style with a raised waistline and skirt falling close to the body. The bodice closes by means of a drop panel fastening in place at the proper right shoulder. Removable matching mitts could be used to cover the arms down to the wrists for warmth or protection from the sun."

The dress is also proof that not every woman in early 19thc Britain - an era much-beloved for the costumes shown in many Jane Austen-inspired films - dressed in plain white cotton muslin. Prints and color were available for ladies who wished to stand out from the crowd, and those who understood the practicality of a dark print and its ability to mask a bit of dirt between laundering.

Woman's gown and mitts, printed to shape, Great Britain, c1805. Collection, Colonial Williamsburg.

Photographs upper and lower left courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg.

Photograph right ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on April 23, 2017 17:00