Brooks Rexroat's Blog, page 3

April 28, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #34: Working Writers

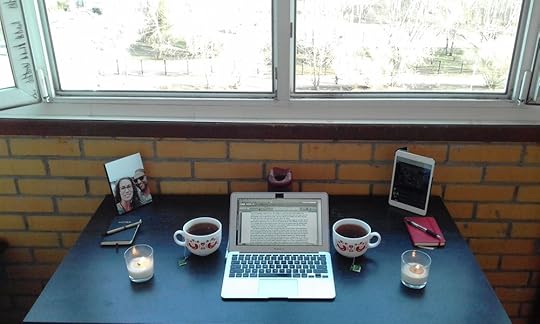

There is nothing so delightful as a nice writing room. For me, that means a space that’s spare and plain with a desk and an electric outlet nearby. Perhaps the most important attribute is a nice window, looking out on someplace where there’s at least occasional human motion. My sixth floor flat has just such a space, but it’s been functionally obsolete for the last six months. The windowed porch off of my bedroom has taunted me for months. It’s just too cold to work out there in the winter, and the extra space it leaves between my bedroom wall and the external window means that I haven’t really had a view while working. This week, I finally grew confident enough in the weather’s stability to move my desk outside.

I should preface what I’m about to say by clarifying that I feel like I’ve been an incredibly productive writer during this trip. I’ve completed two books that were in progress when I left the states, completed a major revision of another, and I’ve written more than 100,000 words of fresh texts, accounting for substantial parts of at least seven new book-length projects. I think that has to count as a successful writing year under just about any definition.

My new writing digs.

But since I’ve moved the desk, my productivity has exploded. I now find myself in the middle of another big revision project, and last week I finished up a new manuscript in time to make a deadline for a press that I admire and think suits the work beautifully. I’ve written endings this week for two short stories that had flummoxed me for months. These still need revision work, but it’s a big milestone, seeing the work in a form that feels complete, if not finished (two very different things to a working writer). I’ve gotten excited again about projects that had been dormant for weeks or months. I’ve begun to outline brand new projects that will hopefully get some of my time during a summer that promises to be one of the busiest and most intense of my life.

All this is to say that a tiny change can sometimes make an enormous difference. My desk moved perhaps two meters from the place where it rested for the winter, but suddenly there’s a calm breeze and the motion of students walking to and from classes at the university across the street. This tiny adjustment had infused life into the things I’m rushing to complete before the clock hits zero on my trip.

And there’s a bigger picture, too. I don’t think the bust of energy comes solely from the new view. In part, I think it’s just change, generally, that has ignited me. Change in weather. The impending change of location. Change of sightline. And of course, the change that comes when a long-term project can finally be crossed off the work leger.

The blissful weather has offered more chances to run--and this is the starting line of the waterfront park running path. When I run, my ideas get to roam. Running, then, is resposnible for the rant which follows.

A few paragraphs back, I mentioned working writers, and I would be remiss not to mention what I feel is a grave development in the writing world, one that took place this week at one of America’s best-known media conglomerates. One of the things I’m most frequently asked to talk about in Russia is journalism. Most Russians I’ve discussed this discipline with have developed the notion that their country’s press could and should be better, freer, and more robust, but no one seems quite sure of how to go about this. While I always decline to try and solve that question publicly, it’s something Russian writers and thinkers are wrestling with, and I’m always happy to share my own experiences and things I’ve encountered.

Unfortunately, one of the things I’ve encountered is the sight of a skilled, well-trained writer carrying her or his belongings out of a newsroom in a cardboard box because the company couldn’t financially sustain the good work they were doing. The same thing happened this week at sports broadcasting network ESPN, a broadcaster of live sporting events, sports-related news, and athletically focused commentary and special interest programming. Companies sometimes have to down-size or “right-size;” I certainly understand that from my time as a business reporter. But the specific cuts were very telling, and they follow a disturbing pattern. Just like politically and news-focused outlets have done in recent years, this purge sent more than one hundred skilled journalists, trained and practiced in the hard business of seeking out and then sharing the truth in a clear, careful, and concise fashion. It’s notable that largely absent from the cuts were the celebrity commentators and analysts—highly-paid former athletes who spend their days offering opinion and not much more. So one more time, one more media outlet has given the boot to truth-seekers and retained people who make things up in the name of entertainment. As has happened to their counterparts in the worlds of news and politics, executives at the company andnits parent corporation will certainly scratch their heads in disbelief as, during the coming years, public trust begins to erode in the network’s trustworthiness. The pattern is as tired and predictable as it is destructive; each time this cycle plays out, the remaining actual journalist bear more and more of the blame and angst that rightfully belongs to the interloping commentators, who should’ve never had their names on a masthead to begin with.

So, what does all this mean to an American abroad? From kindergartens to universities to media organizations and the arts, the rest of the world looks to America for leadership, guidance, examples, and possibilities. Russian, Asian, and European universities are reshaping their way their collegiate degree programs are run in order to grow more compatible with our system and encourage international exchange of ideas. Eastern newspaper operations are borrowing techniques and methods from their American counterparts.

The rest of the world watches how America operates in these fields, because the country has a long tradition of innovation. The problem is, just as everyone else looks to the U.S. for ideas, we’re walking away from the methods that made those institutions great in the first place. We’re treating our universities like businesses, expecting state colleges to turn a profit or sustain themselves—a major shift from the historical perspective that an educated public was worth the collective expense that went into making higher education affordable for anyone who showed the ambition and ability to pursue higher learning. Another step in abandoning the same principle: we’re treating universities as job training sites rather than centers for the transfer of knowledge. This over-specialization comes at a time when the job market is shifting so rapidly that generalized learning and academic agility are more valuable than ever before. And so our response is to seek out the opposite solution, because someone got it into America’s head that everything can and should be run like a business, and this simply isn’t true.

In news that's slightly sunnier than the state of American journalism and corporate hiring practices, it is officially cold brew coffee season in Siberia.

Across the globe, our counterparts are adopting our best ideas while we abandon them. I hope they hold tighter and faster to these good methods than we have, and I hope it brings success to the nations bold enough to hang onto principles larger than individual profit. If the new American ethos is, indeed, to manage all aspects of society as profit-rending business enterprises--and if the unfortunate offshoot of that ethos is a mentality of perpetual competition between nations--then perhaps it would be wise to stop abandoning our richest ideas and institutions, the ones coveted by nearly every other society.

The opinions expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State.

April 21, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #33: Collecting Experiences

This has been a week of contrast. Half of my mind is on tying the loose ends and enjoying the last few weeks of my time overseas. The other half is planning for what promises to be an exciting and busy summer back in the U.S. Half of the week was sunny and warm. Half the week was rainy backed with a brutal, chilly wind. I went for a run on Wednesday, the first chance I’d had to do so in ages. It was nearly seventy degrees. Half the university’s track was clear and bone dry, the other was still caked in a meter of built-up ice. Opposites and dualities all over the place, but in the end it’s just more opportunity and adventure.

As has been the case in recent weeks particularly but during most of the trip, much of the week was spent hunched over my laptop, plowing forward on a seemingly unending list of projects. I’m editing old stories, writing new ones, reading student drafts, planning essays, finishing forms and paperwork, fin It’s a fine line to walk: there are things that need to be done in order to serve my students or finish the research and writing that the Fulbright program has invested in, but the program has also invested in experience and connection, so I have to guard against holing myself up for too long. And certainly, I want to make sure that I soak up every moment, every observation, ever experience and conversation I can while I’ve got the opportunity to be here.

Maybe the biggest sign that my brain is preparing to turn the page and resume thinking and acting American came as I began typing out this blog. Just a few minutes ago, I heard a loud series of rhythmic pops outside. I stepped to my window and looked down, expecting to see a shootout. Turns out, it was fireworks, and I had to remind myself I’m not in a place where half the population walks around strapped.

Last Friday, I got a chance to speak to another large gathering at the Novosibirsk State Regional Scientific Library. One thing that has absolutely impressed me in Novosibirsk is the enthusiastic and consistent turnout for academic and intellectual events of all sorts, from public lectures and book signings to artistic performance, installation openings, theatre, film and more. The library has hosted me twice and I’ll have a chance to begin my move into my final week in Novosibirsk with one more event there, when I present a reading from my own work on 25 May.

Speaking about comparisons between Siberia and the American Rust Belt at the Novosibirsk State Regional Scientific Library. Photo: Inna Pushkareva

For this session, I spoke about ways in which Siberia and my native land, the American Rust Belt compare and contrast. The question and answer session alone stretched on for just shy of an hour, and the crowd was engaged, thoughtful, and curious—the best sort of crowd for such an event. I had an impromptu dinner with a group of inquisitive students afterward, as we continued to discuss the social, cultural, and political histories and debates at work in each of our own regions. It’s always a pleasure to get a chance to talk to interested crowds about writing, but this discussion was unique. It offered a chance to have a conversation about home and the very similar things that word means to folks from opposite sides of the world. That’s a special sort of experience to have, and one that will leave a lasting memory.

And then: an experience of an entirely different sort. On Tuesday, I took a trip to the northeast side of the city for a concert by an Irish band called God is an Astronaut. The music was entirely instrumental—not just the headliner, but the opening band as well. The sound was in the vein of American band Explosions in the Sky (perhaps most famous for their contributions to the soundtrack of Friday Night Lights) and groundbreaking Canadian rock orchestra Godspeed You! Black Emperor.

Irish instrumental rock band God is an Astronaut, live in Novosibirsk.

I’ve been to a couple small shows in Russia, but nothing like this, with north of a thousand people in the audience. It was a wonderful yet strange experience all around, but intensely interesting. The venue doors didn’t open until the first band was already working through its second song. I can’t help but wonder how those guys felt, stepping on stage at the appointed starting time and beginning their set, knowing the thousand people who had paid to see them were outside in the cold, lined up and yet to even be frisked. As we filtered in, we figured they were still working a sound check, but no: it was the performance.

Now, I have to say this is a nice contrast to club shows in the U.S., which can sometimes being an hour or more after their advertised beginning time. But it would’ve been nice to be allowed inside before they began playing. Who knows the reason: perhaps there was a glitch or a missing employee or some other problem—or perhaps it’s normal that door time is also show time.

The venue doubles as both a concert hall and a nightclub, and they had the lighting show to back up the club aspect. Powerful lights and a spectacular show punctuated the music. The only problem: the lights started overhearing the band’s gear, so that by the end of the show they were bypassing amplifiers altogether and plugging straight into the soundboard. The band was more gracious than most would have been. They apologized profusely for the malfunctions, even though it was actually someone else’s rig ruining their gear, and thus their livelihood. That was very Irish of them, by which I mean polite and humble. The show and its confluence of cultures—the band walking in English, the crowd shouting back in a blend of English and Russian—was a nice way to begin the bridge into the final segment of my Russian adventure, since my second-longest trip abroad was to Ireland, a six-month jaunt a few years back. I feel really honored and lucky to have been able to spend time in two places with such different cultural, social, and geographic atmospheres and yet a shared sense of the value and beauty of literature.

Proof that at every general admission show on every continent, the tallest guy in the room will always stand in the front, center so that everyone else may stare at his oddly shaped head for three hours.

Next week, once a few more of my projects are ticked off, I’ve got a last little bit of traveling to do, and I’m very much looking forward to sharing stories and images that I come across during that trip.

Until then, it’s very literally back to the books.

The views expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State.

April 14, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #32: Winter is Receding

Winter is receding from Siberia, which is a great duality. At eye level, it’s heavenly. The air is warming, the coats are turning to jackets, and sometimes just sweaters or even shirts. It feels blissful. It looks blissful. The sun is out, and the days are longer, the breezes gentler, and the people are bright and animated. At ground level, though, it’s a different story. The slow bleed of melting snow piles, combined with the sludge of normal soil and six months’ worth of spreading sand over the building snowpack that helped walkers and drivers keep their grip have turned the ground into a puddle-ridden gob of slimy obstacles--often of ndeterminate depth.

I’ve been assured this will dry, eventually, but there are no signs of that yet. It’s a constant choice, then: stare down at the mess and try to avoid whatever grime you can, or look up, enjoy the beauty, and try your best to scrub up once you’ve arrived at your destination.

My solution so far has been a very Russian one—a very practical one: it all depends on what shoes I’m wearing.

Perhaps a little passive aggression on the part of the sanitation department, but there is NO excuse to litter while seated at this bench. Also, note the presence of non-snowy ground.

Yesterday, I had lunch at a steakhouse (business lunch discounts are prevalent, so lunch is the time to visit all the places that charge more than you’d rather pay come dinner time). The coat man, who occupies a nicely appointed room to the left of the main entrance, rarely bothered to move from his spot at the counter. And yet, even as he knows fewer and fewer people are walking into the restaurant with coats to deposit, he dutifully waits without sitting or complaining, making disappointed facial expressions or otherwise reacting. He just stands and waits, in case.

I wonder what will happen in a few weeks: whether he has summer employment, or whether the restaurant will shift him over to some other duty—or if he’s simply in line to be out of luck and employment until the snow clouds return.

During the time it took for my food to arrive, I wrote a quite short story about such a man—I thought it made a perfect vessel through which to show the impact of unavoidable passage of time.

The same man has been there every time I’ve visited the restaurant, and despite his obvious work to retain the dignity and detail of the position, I couldn’t help noting how very sad he seemed. His face and general carriage were precisely the same as I’d seen on every other visit, but there was an implicit sadness. I’ll wonder what became of him, long after the season has finished changing.

Russian food and beverage: as aesthetically pleasing as it is delicious, as proven by Endorfin Coffee in Tomsk.

I took a fast visit to the university town of Tomsk this week. The town is more compressed and compact than Novosibirsk, but young and vibrant, full of energy and innovation. This atmosphere, which seems present across Siberia, led me to the idea for a lecture I’ll present later today, comparing the American Rust Belt with Siberia. Both are the victims of names that come with some baggage, and even though the systems that created them did so with very different motivations, both regions wound up dotted with single-industry towns that were unstoppable at their peak but decimated when the industry busted. Both regions are also home to incredible, youth-driven “maker” movements, in which young people take advantage of cheap property in previously undesirable locations and build thriving communities based on culinary and craft creations—movements that are re-shaping cities and helping to remove long-held stigmas. The project excited me so much, that I put off building a PowerPoint until the last minute, instead sort of stumbling into the composition of the first quarter of a book on the topic. I’m hoping to have a full draft finished by the time I return to the U.S. in June.

Monument to space program workers in Tomsk. This week, Russians celebrated Yuri's Day, the anniversary of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin's first manned spaceflight.

Before I checked out a neighboring city, I explored a bit closer to home by visiting the Novosibirsk circus. Circuses operate differently here than I’m used to. In the U.S., there are a couple of large circus productions which tour the country, stopping to present a couple of shows for a community before moving on to the next town. The largest of those, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, will hold its final shows next month after deciding earlier this year to shut down operations. A couple of smaller, regional operations work on the same model, touring within smaller geographic spheres.

The Novosibirsk Circus (Image: Margaret Adams)

In Russia, each town of a certain size has its own dedicated circus building, and a production company. Much like the opera house or symphony, the stationary operation changes performances throughout the year. This month’s, for example, was a water-themed show, with everything from dancing seals and canoeing clowns to synchronized swimming and trapeze performance above a pool of water.

The performance was packed, and the performers were tremendous. The building was old but it served its function—well except for maybe the restrooms. I understand the festive, shiny nature of circuses, but without getting into any of the hundreds of detailed and specific reasons why it’s a poor choice, let’s just all agree the mirrored ceilings in the men’s room need to get replaced. Aside from that little hiccup, though, the experience was an absolute joy.

There’s nothing quite like a circus to revitalize a wide-eyed and wondrous view of the world. The contortionists and acrobats showed how far the limits of the human body can be stretched. The clowns are a nice reminder that sometimes, we’ve got to stop taking ourselves so seriously and enjoy the goofy thing that is life. And though I respect everyone who works on behalf of animal rights, no one will ever convince me those seals are having anything short of a blast as they balance on a fin while nudging a beach ball skyward with their nose.

Those Russian lines I've written about all year? Well, this is the coat room queue after the circus.

As all this happened around me this week, it was a good reminder: there are gross puddles on the ground and wonder in the world if you look for it. So put on some shoes that you don’t mind ruining and keep your eyes up—soak it all in and live.

The opinions expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State.

April 7, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #31: American Stuff While Abroad, or, The Long, Slow Death of Baseball

In my hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio, opening day of baseball season is a civic holiday. There’s a parade, a street party, and local and national celebrities attend the game. Someone important throws out the first pitch, and on those blissful years with nice weather, the city basks in the glow of the oncoming spring.

This year, for the first time since I figured out what baseball was—somewhere around the age of four—I didn’t care. And it had precious little to do with my being overseas.

Baseball is America’s pastime, unofficially and colloquially, at least (although I suspect our real favorite pastime is quickly becoming the petty online argument). Baseball was my thing, all the way through youth. From second grade through middle school, every daily journal entry assigned by teachers somehow meandered back to baseball. When I was nine years old, my hometown Cincinnati Reds unexpectedly won the World Series ( the name for professional baseball’s championship, although it only includes teams from only two countries), and the fervor gripped me even deeper.

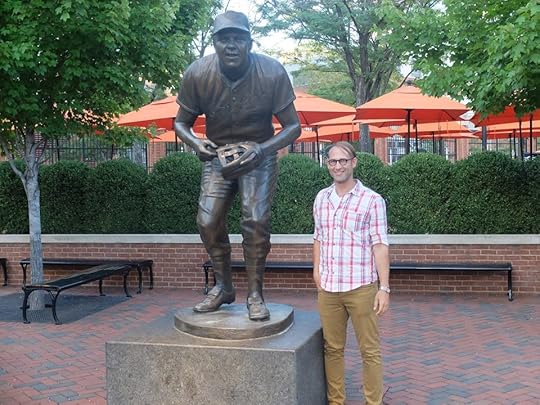

Next to a statue of my namesake last summer in Baltimore, Maryland.

That year, I also met my namesake, the hall of fame third baseman Brooks Robinson. Famous for his tireless work ethic that turned him from a boy of middling talent into an all-time legend at his trade, I disliked him deeply throughout my childhood. See, what I knew of him came largely from grainy video clips that showed him almost single-handedly handedly dominating my favorite team in the 1970 championship. As a kid, that was the worst thing I could imagine: being named for someone who dominated my team. I never understood why Dad could have burdened me that way—until the afternoon I met Mr. Robinson. He wept openly in front of a line of autograph seekers when my father explained I’d been named after him. Then, he bought a camera so he could have a copy of a photo with me, and then he called me to his side and talked to me while he signed autographs for the rest of the line-waiters.

So, here I am a couple decades later, an American in Russia on opening day. I should be preaching the word of the real beautiful game, right? I should have been tuned into the parade and the festivities, maybe even telling Russian students about the game and why it’s so integral to America and the American psyche.

But like everything else in America these days, it’s more complicated than that.

I still love the game itself: the beauty of it, the mixture of strategy and strength, elegance and power. But it’s also one more thing that’s on the brink of being ruined by money, and the very thing my hometown celebrated this week is the thing that’s brought the sport to the edge of being unwatchable. See, the reason Cincinnati is so bonkers about baseball is that the city was home to the first all-professional baseball team, and one of the first all-professional sports teams generally. That was wonderful when the 1869 Red Stockings were barnstorming the country and racking up a 57-0 record, but these days, it’s led to the absurdity of $10 million contracts for situational backup players—prices that allow just a handful of teams from major media markets to remain competitive.

Speaking of feats of strength, this Soviet-era doll currently on display at the Novosibirsk Regional Museum seems to have followed Barry Bonds' diet a little too closely.

The commissioner of professional baseball is on an ongoing mission to save the sport, which is losing viewers, fans, money, and potential players to other sports and entertainment pursuits. His thesis is that everything can be fixed by making the game shorter, which has led to a series of odd and largely misguided rule changes in the past few years. But that’s not the problem. The problem is ballooning salaries that cause small market teams to trade away beloved favorite players before they become unaffordable. The problem is an overreliance on math and technology that largely undermine what the sport really is: an athletic contest. The problem is a focus on individual superstar players rather than a local team.

The problem is that none of the actual problems will ever be fixed, because they’re making someone rich. Superstar players sell memorabilia and products. Math and technology fuel fantasy sports. Ensuring success for the wealthiest teams and owners—well, I haven’t really figured that one out, since they seem to be doing well enough on their own.

Last year, one team began employing laser pointers in its quest to squeeze the last drop of sport from baseball. From the bench, the defensive team’s coach would call a pitch. Somewhere in a booth, mathematicians ran a simulation of the batter’s tendencies, then flashed honest-to-god lasers on the field, showing all the defenders where to stand. The batter plunked the ball harmlessly toward a player who was standing in the perfect spot. No need to run or strain. No room for heroic tales or storybook endings of overcoming the odds toward an unexpected victory. No hometown heroes to celebrate, because they’ve all been sold to the teams with enough money. These days, America’s once-favorite sport is just a human video game with expensive snacks between innings. So this week as baseball season began in America, I didn’t regal my Russian friends and colleagues with stories of the games virtues, because frankly, I’m not sure it’s got any left.

Next week, we’re back to adventures in Russia.

The views expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the U.S. Department of State or the Fulbright Program.

October 7, 2016

Dispatches from Siberia #5: Rust Belt Vs. Siberia

September 30, 2016

Dispatches From Siberia #4: Winter is Coming (and everyone loves to say so.)

September 23, 2016

Dispatches From Siberia #3: Language Creates all the Problems–Then Solves Them

September 16, 2016

Dispatches From Siberia #2: Where I am and Why

September 9, 2016

Dispatches from Siberia #1: Few Bears, Much Coffee

June 23, 2016

Interview Posted at Speaking of Marvels