Brooks Rexroat's Blog, page 2

March 23, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #41: Homes

“What place do you call home?”

I heard this question a few days ago. It wasn’t addressed to me, but it’s been bouncing around my mind since then, and it’s a deceptively hard question.

In one sense, home is very different for my wife and I, so when someone asks where we’re from, there’s always a short pause, and we always look at each other, as if to ask, how are we going to answer this time?

In another sense, home is where she is—where my family is. Homes are where I’ve been, where I’ve spent time. I consider Novisibirsk one of those homes. Galway, Ireland? That one’s a stretch. I lived there, to be sure, but it never felt like home. I was there about five months, but it just doesn’t seem the same. In both places, I lived and worked. I stayed in one just a bit longer than the other. The difference, I think, is the quality of connections and relationships made during the stay.

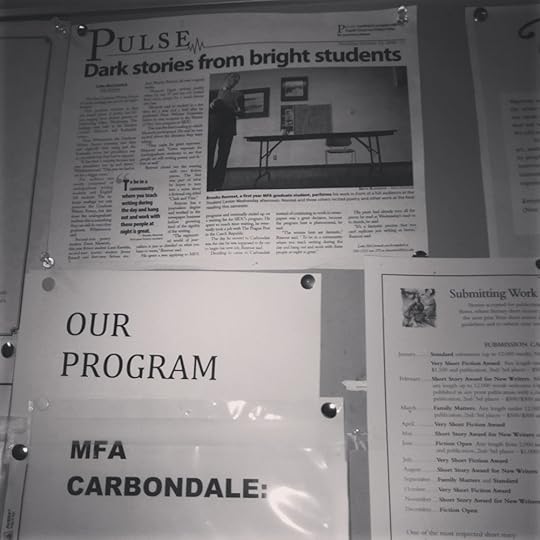

That’s the qualification of home that sits with me this afternoon, as I sit in an old favorite spot, in an old home. I’ve come back to Carbondale, Illinois, home of my postgraduate alma mater, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Tonight, I’ll read with a pair of my contemporaries, two writers with whom I studied during my time in the SIUC MFA program. I finished that degree nearly seven years ago, and I’m thrilled to return as a guest graduate reader at the English Graduate Department’s annual academic conference.

Appropriately enough, the conference is titled, “A Changing Landscape: Shifting Borders and Slippery States.” That title felt particularly appropriate this morning as I drove past block after block of plowed-over and recently gentrified memories.

It’s swank of Carbondale to have an Insomnia Cookies franchise now, to be fair, but I miss the old, gritty Carbondale, the one that gave birth to the ideas of many stories that populate the book from which I’ll read tonight.

This Carbondale is someone else’s home now, those there are smatterings of the one I remember peeking through the freshly painted version of town. But it was a home, and it feels good to remember it that way. It feels good to remember the other homes, too: Cookeville and Chattanooga, Siberia and Ohio Morehead and Huntington. There will, likely be more homes and more stops, more memories, and more iterations of that question: what is home to you?

The answer, likely, will be as vague then as it is now, and just as heart-tugging.

Home can be: Places.

Home can be: Food.

Home can be: Memories.

March 2, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #40: Results

This week, I got copies of the final edits of my novel and photos of the prototype paperback version of my story collection. Both of these projects got series work while I was in Siberia, but both projects reach back years. It’s been a week of results—the best of which tend to come after long, long waits.

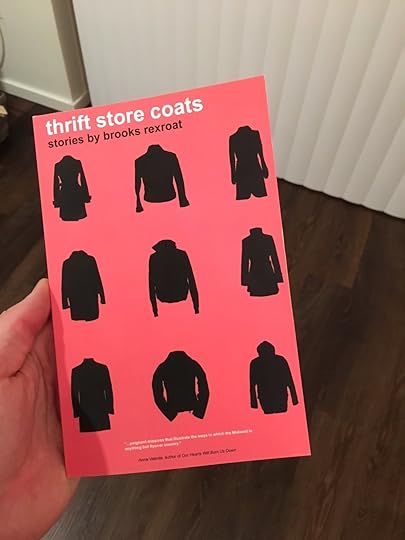

Physical copies of Thrift Store Coats have arrived at the Seattle offices of Orson's Publishing.

I got results this week, too, from a couple of literary journals. For those who aren’t intricately versed in the publishing world, most of it can be summarized like this: writers spend a long time composing, then send work to perspective publishers, attempting to match subject, tone, and character type to publishing homes that might have some interest. After the submission, there’s generally a long wait, followed by some variation of the phrase, “No, thanks.” The odds get a little better with experience and skill development, but generally writing is about waiting for and reacting to the word “no.” In the end, for those with the patience to wait it out, the word yes finally comes, and it is a sweet thing, followed by the inflated sweetness of the things that follow: the care editors take in continuing the honing process, the arrival of a product, the reaction of the audience. It’s a thing seldom experienced, but indescribably wonderful each time.

A state away in my former home, teachers and colleagues I admire deeply are fighting for another result. They, too, are putting in the work and waiting, just to be told no again. Not by publishers, but by politicians.

For the seventh day, teachers in West Virginia are on strike, seeking some semblance of fairness in pay, health care stability, and general respect from the governing bodies that represent them.

Each day, thousands of teachers including members of my family, dear friends, colleagues, former students, and acquaintances from my time in Huntington are joining their peers from across the state to demand in their loudest and firmest voices that simplest of things—respect.

For decades now, politicians have mangled the fact that public teachers garner salaries from the state into an excuse for derision and slander. In the Mountaineer State, they’ve tired of it. The slander still showers on them from certain parts of the political world, but the public seems to be getting the gist: public service makes teachers something closer to hero than anathema.

West Virginia teachers gather at the statehouse to protest proposed benefits changes and demand market pay. Photo/Don Scalise (@don_scalise)

A framework deal was struck earlier in the week, but as too frequently happens, there are obstructionists more invested in personal gain than public good who block, negate and shout from their elected spaces, “No.”

The good teachers in West Virginia—as well as the miners, professors, and public workers, and laborers who have joined them—will be told no plenty of times. So will the teachers of Pittsburgh, should they follow through with a planned strike of their own, and those around the country, should they follow suit. But when the result comes, it will be sweet. Every time.

Brooks Rexroat was a 2016-2017 Fulbright Scholar in Novosibirsk, Russian Federation, who now teaches at Brescia University in Owensboro, Kentucky. His debut short story collection Thrift Store Coats, explores working life in the postindustrial Midwest.

February 2, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #39: Time and Space

One of the best ways to relax between manuscripts: a steady blend of waffle and pastry. And yes: that's a beaker full of liquid chocolate.

I am exhausted.

The last two weeks have been an unending flurry of motion: catching back up from a week of classes and meetings missed due to snow cancellation, the construction of and scheduling (together with a group of my students) a brand new visiting writers series to be launched next month at Brescia University, the logistics and fun of coaching the first indoor track meet of the season (I coach at a local high school, alongside my wife), and of course the excitement of my debut book going on sale, and the promotional magicianship that’s required by such an event.

I’m wiped out. All of my energy feels gone, though plugged into good things.

And it’s made me look back on my Fulbright year in a very different context.

Frequently, I think about the experiences I collected, the connections I made, the places I walked, and the beauty I encountered. I’ve written about these things in previous posts, both from inside Russian and stateside after my return. But there was an unspoken dynamic to the year, one that doesn’t get as much attention or affection.

Perhaps the most powerful offering of my Fulbright grant was time and space.

This was hard to see in the moment. There were mornings when I woke in that Siberian flat, staggered to my desk, and forced myself to write because I was there to write and writing is what I needed to do. There were afternoons when I took time off to visit a restaurant or grab a cup of coffee—with (gasp) no computer in tow. I felt some guilt at this, as though the backing of government funds and the selection by an academic panel meant I must work without cease.

This wasn’t the case.

The deeper I got into my trip, the more comfortable I felt in occasionally relaxing. And the more I relaxed, but better my work became. Let’s be clear: I did plenty of work. My best count is 400,000 words of new work—roughly half the length of the protestant bible—in addition to two book-length revision projects, and my teaching work. This output was possible, though, only because I took more rest, more trips, more deliberate and thoughtful breaks than I’ve ever attempted. When I was resting, it was the art museum or a Georgian restaurant instead of Netflix.

Lots of folks subscribe to the idea of writing each and every day, whether the output feels worthwhile or not. I understand the impulse and tactic, but it doesn't work for me. I tried to make it work, the first couple months of my grant. But as time wore on, I felt freer--freer from a number of standard job requirements. I could write in a more leisurely way than I ever had, and as I bought into this approach, the work got better, less forced. Sure, there were days I labored in front of the computer screen for a dozen hours, but when that happened, it was because I felt I had something to say, not just compulsion to work. Extra time. Extra space. Extra freedom. It all blended into more and better work--and more joyous rest between.

Not every season of life gives ample opportunity for purposeful rest in between and during projects. But my time abroad taught me to incorporate that necessity into work—at least, when I can.

If the waffles fail to inspire, a stroll on the bank of Lake Baikal won't.

January 19, 2018

Changes

Last month, as I took the last of my few things stored a my childhood home, I looked back to find the most appropriate view: the house swallowed up in trees we'd planted.

The first time I ever bought a cup of coffee was about three days after I got my driver’s license, and the drink had nothing to do with wanting to feel grown up, or wanting to emulate Dad’s morning cup or anything like that. In fact, that first coffee had nothing to do with coffee. Exploring the new freedom of life with a vehicle, I’d gone to the logical first place: the bookstore. I would get to stay as long as I wanted this time, not rushing for a waiting parent who had someplace more important to get, or the next stop to move toward on a chain-shopping trip. I explored the place top to bottom, section after section, but at a certain point, even a 16-year-old begins to feel self-aware about wandering endlessly through a shop with no potential purchases in hand. Eventually, I wandered over to the café and bought a small coffee, then played copycat on the adults that populated the tables: I grabbed something from the periodical rack—I’m pretty sure one of them was a copy of the Prague Post, which was at that time sold in a number of U.S. book shops—and plopped down with my coffee and a free read. I bought a paperback or two before leaving, which was a big deal for a kid whose income was paid yardwork for the folks, at least until hay and straw bailing season would begin a few weeks later. Then, I’d make some solid money, but for the moment, two books and a coffee was a pretty full day of expenditure.

This morning, I’m again in the café of a bookstore, again in love with the smell of 10,000 books around me, colliding with puffs of steam from the espresso machine behind me. There are other places to loiter while I work, of course—home and my campus office and cafes both corporately and locally owned. But it’s always been here, surrounded by the written ideas of others. And it seems like the right place to cap a week that’s been filled with news ranging from openly joyful to bittersweet at best. The home I drove back to after that first coffee was sold today. Earlier this year, my parents downsized their home, and while I’m happy for them in that regard, that was the home I always came home to: from college and work, from grad school and at holidays, on long weekends when I just needed to be someplace familiar around someone familiar. It’s tough, knowing I’ll never again drive home to that grey house behind the pond.

Like the sale of that old home, the rest of this week’s news has been a long time in process.

My first book has been published—in Russia. Last year, Russian linguist Olesya Valger and I co-wrote and co-edited a textbook called Stories From the American Rust Belt With Case Studies in English Grammar. The text, published by Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University Press, includes several of my stories, along with exercises and practical details to help second-language students of English interact with contemporary American literature. As I understand it, some printed copies are in the early stages of transit, and I’m looking forward to holding a copy soon.

But that was just the start of good book news.

On Tuesday morning, Seattle-based Orson’s Publishing released my debut story collection for pre-order. Print copies will ship in April, and ebook copies will be available at that time, as well. When the book was announced this week, some of the first questions I received were connected to my time in Russia—namely, whether this was the book of stories I wrote while overseas. It’s not—though I continue to work on those. However, this set did get some substantial editing and revision work during my Fulbright grant, and I submitted it to the press from my flat above Vybornaya Street.

The collection runs the gamut of my writing life: the oldest story got its start during my first month in graduate school at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and the newest one was completed last Autumn in Siberia—it made the trip with me as a half-finished stub, and I finally did enough surgery to it to make it feel like a story that belonged in a set.

For much of the last year, Publisher Garrett Dennert and I have pushed and pressed each other and wrestled this thing into a book I’m extremely proud of, one that traces the lives of workers and workers’ kids and retirees in the post-industrial Midwest—the Rust Belt. It felt right working on the collection in Siberia, which in many ways knows a similar history: regions of single-industry towns left to rise and fall at the mercy of economy and other, connected single-industry towns, places trying to reclaim names rife with disparaging stereotypes, regions full of youthful, vibrant generation set against the remnants of past decay. The collection has busted-up factories, yes, but more importantly (and I think more interestingly) it focuses on what the people do after they walk out those doors for the last time—something I can connect with this morning.

A final piece of exciting news: Peasantry Press, the publisher of my forthcoming novel Pine Gap, sent final edits this week, and work has started on cover design. Review copies should be heading out soon, and by the end of the year, it’ll be a trio of books with my name on the spine so that someday, some kid with newfound freedom and a set of keys might just buy a drink as an excuse to linger, and when they do, maybe, just maybe they’ll pull one of those books or its neighbors from the shelf. And if they get to travel the same path I’ve gotten, one full of words and daydreams, a trail of ideas and travelling friends that stretches from Illinois to Irkutsk—well, they’ll be immensely lucky.

The finished product: the cover art for my U.S. debut in book-length fiction: Thrift Store Coats.

January 12, 2018

An American Snow Day

Snow: Jan. 18, 2018, Owensboro, Kentucky, United States

Note: From August, 2016 to June, 2017, author and educator Brooks Rexroat lived and worked in Novosibirsk, Russian Federation as a Fulbright Scholar in creative writing. Originally designed to chronicle the author’s time abroad, Dispatches From Siberia now examines the questions, challenges, and epiphanies of returning home after a life-changing trip.

A year ago today, I was trekking through the snow-piled backstreets of Novosibirsk, Siberia. Three months of continuous sub-freezing temperatures and consistent snow had glazed the city—including roads and sidewalks—with a meter or more of compressed ice, atop which we drove, walked, slid, and helped each other up. Not once in the six frozen months of my nine-month Siberian residency did I note a school, business, or government office shut by weather.

Last night, with the temperature hovering just above sixty degrees Fahrenheit (18 degrees Celsius), I received in rapid succession a phone call and a text, explaining that the university where I teach and the public school system where I coach would be cancelled the following day, in anticipation of bad weather.

I laughed at each.

But not for long.

More than anything, I was excited for the first significant snowfall I’d seen and felt since leaving Russia. Aside from a few flakes in West Virginia on Christmas Eve and a dusting on the ground the next day at my folks’ home in Ohio, I hadn’t seen a speck of it since the stubborn last ice hunks of Novosibirsk melted off, sometime in late April. Instead of bunkering down in the apartment, I de-iced my Volkswagen and headed out to enjoy the frosty day and to remember the blessed cold and familiar white ground I’ve missed in the aftermath of my trip.

Owensboro Kentucky was, in large part, a ghost town. The few vehicles on the road were either creeping along with exorbitant caution, or plowing past everyone, honking and spraying snow slurry on their neighbors’ windshields.

Ah, America: the land of opposing forces, from politics to driving technique.

As I drove, and then plunked myself down in a nearly empty café that would be bustling any other day at the onset of lunch hour, I couldn’t help thinking of the ways in which Siberia came to its most alive state in the depths of storm: the way the people walked with huddled purpose, the way the bus drivers skirted the line between efficient delivery mechanisms and daredevil lunatics.

The circumstances, of course, are entirely different. Siberians understand the snow, the physics of staying upright on ice, the methods and techniques of surviving brutal temperatures and shrugging off slick surfaces. Kentuckians, as it turns out, are not.

Part of the difference stems from lack of practice. That’s something that’s been hard in coming home. I grew to love the snow, the cold, the consistency of the days. I miss it, and miss it dearly. Practice with snowy, cold weather can do a lot for one’s development as a human: it teaches patience, care, precision, teamwork, preparation, thoughtfulness. A good battle with the elements every now and then can be good for the body, mind, and soul. And I miss it.

A larger reason, though, is the fundamental mode of transportation. In my new Kentucky home, I can’t get anywhere without driving. Anywhere. The trash compactor at our apartment complex is a good kilometer of meandering twists from our door and requires a drive. Public transport—even if we relied on it—couldn’t get us to a fraction of the places necessary to comfortably function. My Russian students, despite the piled snow, had it easy: they could step out their doors and take a short walk to a transport station—bus or metro—and get anywhere useful in the town. It might take a while and the bus might be crowded, but I would arrive.

The sense of rampant, overeager individuality that so limits America and Americans runs far deeper than the handful of drivers who imagine their oversized pick-up trucks give them license to run the rest of us down.

It comes in spacing ourselves out, prioritizing land over community. It comes in inverted ideas over land value—in America, single-owner homes are heavily favored by those with the physical means, while in Russia, the conveniences and connections of a high-rise apartment block—even if it’s old—are still dearly desired. It comes in our vapid avoidance of investment in community transportation, at least outside our largest cities, which have resigned to its necessity.

On that trek through frozen Novosibirsk with an American (a previous Fulbright Scholar still living and working in Russia who had returned for a visit to his former home) and our Russian guide Mikhail, we were examining building techniques in the suburbs. Our guide, a well-known activist particularly invested in safe zoning and building requirements, pointed out numerous styles and formats of building, some safe and painstakingly crafted and others, well, not so much. Most of the homes were constructed of found (and sometimes incongruent) materials, but it was the macro view rather than the micro the caught my attention. Stepping back and examining the neighborhoods as a whole, they looked shockingly different from the rest of the Russia I'd encountered. Most of the homes looked like they’d been torn straight from the design book of a Midwestern American subdivision.

These suburbs, Mikhail explained, were home to some of the poorest people in the city, but also some of the most ambitious and industrious. He showed us his own home, which his family had built by hand.

There was pride in a job well done, and it was inspiring. But a look around the neighborhood showed something more ominous: the desire of a certain set of Siberians to live a life that at least looks and feels like America.

This morning, it took nothing more than a quick duck out into an American snow day to remind me that perhaps that’s not the greatest plan. Perhaps Americans should look to become a bit more Siberian.

I survived the snow and made it home, then sat down at my desk where my familiar beige matryoshka doll smiled at me as I sat before my window to write, just like it had each day in Russia. For the first blissful time since returning home, I opened the blinds and saw the gorgeous tone of light that only comes when the sun reflects of a snow-covered earth. As much as that light warmed my spirit, the stillness, the lack of life outside saddened me and I could not help but pine a bit for my old perch, the window of my warm flat high above bustling Vybornaya Street.

Brooks Rexroat is the author of Thrift Store Coats (coming this April from Orson’s Publishing) and Pine Gap (due in 2018 from Peasantry Press.) Reach him on Twitter, Facebook, or at brookspatrickrexroat@gmail.com

Snow: Jan. 12, 2017, Novosibirsk, Siberia.

June 28, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #36: Success by Degrees

The last three weeks of my Russian adventure were a whirlwind: so much so that I often didn’t have time to record my thoughts or, if I had time to record them, I didn’t have time to post. What follows is a blog from the week of 21-25 May, which includes my first international racing experience.

Within the span of about 12 hours this week, I lost the credit card that was my lifeblood during the span of my Russian stay, my iPad’s power cord died, and the elevator button for my floor in the apartment building quit working. My computer power cord—my second this year—is nearly burned through from the extra voltage, and my computer itself has had enough European 220 voltage coursing through its veins that powering up is nearly enough to make it overheat; suffice it to say when I meet with Brescia University’s human resources folks ahead of my first day on the job, I’m heavily considering setting up my direct deposit for the first semester using Apple’s bank account instead of my own. In the middle of the month, the city shut off the municipal heating pipes, and as part of the annual inspection process, water was shut off for my street. It’s been nine days of baths drawn one boiled tea kettle at a time, and no end is in sight.

I’ve had an amazing, informative, invigorating, grueling, challenging and love-filled time here, but even the stuff I use to get through life is worn out, quitting, and ready for me to go home. I’ll do that in just about two weeks.

Before going home, I had to ring up a couple of final, short trips to neighboring cities I’d wanted to explore. One of those was Barnaul, a city which has a proposition for a new name but also a fascinating history and above all, a beautiful geography. By the time I arrived, though, perhaps the biggest attraction was the working shower.

When someone asked me Saturday night what I did in Barnaul, my answer probably sounded uninspiring: I wandered around the city, essentially, took some pictures and ate. That was really the essence of what Barnaul offers on a very short trip. There was a sold-out rap show happening at the arena, and there were plays and an opera that had just wrapped the night before I got there.

Monument to space exploration, Barnaul, Russia.

I began to enter a nightclub near my hotel, but when the bouncer told my I’d have to remove my very blazer-like jacket because it had a zipper and could be dangerous in a fight, I decided that wasn’t the spot for me and made an about face out the door and back to the hotel room.

I took several nice runs: two at a track near the hotel and another through the city, and those were relaxing pieces of the mini-trip.

I also met up with a fellow Fulbrighter for coffee and together we explored the flea market in the central park. My prize haul was a five-inch metal bust of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, along with a couple of pins that nearly finished my collection of towns I’ve visited in Russia.

The Barnaul skyline at twilight.

My return from Barnaul was frantic. After getting off the four-and-a-half-hour bus ride, I had to visit the regional library, where packet pick-up was taking place for the race I’d signed up to run the following day, the Za-Beg All-Russia Half Marathon. (I’d just signed up to run a 10-kilometer segment of the course, which proved to be a very wise idea.

In a couple weeks, I’ll be charged with giving some advice to next year’s crop of Fulbright scholars at the annual pre-departure orientation in Washington, D.C. One of the most important pieces of advice I think I can give comes in two phases. First: try new things. Try all the new things you can, whenever you’re able. But second—and no less important: try the things you normally do in a new context. Try going to a burger place and enjoy the Russian take on something that’s been familiar for a long time. Go to an old movie house and marvel at the freedom—and questionable decisions—of people rolling in with their own food and drinks from home. Run a road race, like I did last weekend.

Here’s the thing: that race was fancy. Anything you could ever ask for was there on the Wow scale. The starting line had a stage and a live band on top of it. There were jugglers and clowns along the course to distract from the pain. The refreshment stations offered choices of bananas or citrus options. There were pace runners with balloons on their wrists showing their target time.

But…there were no clocks, anywhere. The one thing absolutely vital to the event, and it was absent. I found this to be a particularly apt wrap-up of my time in Russia: all the bells and whistles are present, but sometimes when it comes down to the core necessities, well, they’ve been left at the door.

Pre-race training, with apple juice in tow.

So I trusted the pacers and followed their lead. When the hour and ten minute and then the hour and twenty minute pacers rolled by me, I kind of packed it in and switched my goal from a respectable (for me) time to just finishing the darned thing. My legs and back were beyond dead from the previous night’s festivities, my stomach was in a perpetual cramp most of the race, and the blister underneath a toenail on my right foot was wreaking havoc on my mood.

And then I finished.

Proof that I did, indeed, finish.

And then I got a text with my chip time. Those pacers weren’t on their A-game, let’s just say. My time was about 20 minutes faster than I’d been led to believe, and there was some instant regret: I wish I’d pushed it a little more in the race’s last quarter, when I’d pretty much tanked it.

I’ve been to races before that had literally nothing but a spray painted starting line and a clock. This one had everything but the time. There are some cultural implications to that that I’m still trying to process, and I’m sure much of it is associated with making the event fun and accessible in an attempt to grow the country’s running culture, which makes sense. But the important thing is that the encounter was a new lens on a familiar event, and that’s one of the best outcomes of an away-from-home experience.

But in Russia, Yuri Gagarin gets all the medals. Even mine.

When I was a little boy, I dreamt of representing America in international races. I ran laps around the high school track as a kid, and in my mind, the eight rows of aluminum bleachers were replaced by a sold-out Olympic stadium. As I grew up, I realized my body was not built for that reality. With age sometimes comes the wisdom of degrees, and for me, the reduced degree here was that I got my chance to represent America overseas, even if my Team USA jersey was leftover from two Olympic games ago and bought in the clearance rack at TJ Maxx. Not the glamor I’d hoped for. And yet, there were actual international runners in the race, from a handful of countries around the region. And I fought as hard to get to run as I did to train my wintery body into a passable runner over the span of just a few weeks. Before I could run, I had to be approved by a Russian doctor, which meant a cardiogram and physical once-over. The weather, as Siberia worked to exit winter, gave me pause every morning leading up to the race as I waffled back and forth over whether it was really worthwhile.

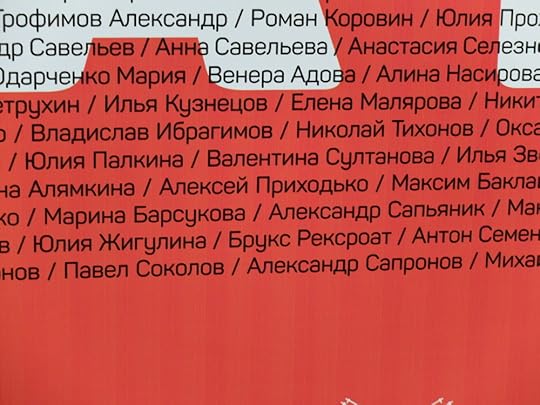

The wall of participants...

In the end, I’ll look back on this experience fondly: a chance to do a tiny fraction of what had been a lifelong dream. Fractions, sometimes are all we get, and they’re far too easy to pass by. So take them, when you can, and enjoy.

...upon which I found myself.

Fulbright Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State.

June 13, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #35.4: The Rest of St. Petersburg.

Thursday:

I caught up on some emails and rushed through the hotel's free breakfast before hurrying toward the Alexander Column to meet up with a walking tour. I made one quick stop—or so I thought—for some coffee in a basement café. I asked to an Americano to go, but it was brought out in a porcelain mug. I’d have asked for a paper cup, but it was small enough to manage in a couple of gulps before I headed on my way. One thing I noticed throughout the duration of my trip is that there is a certain cadence to ordering food and drink in Russia. If you fall out of it—and I was never really able to nail the thing down—it’s a good bet that something will go funny. In my case, there were several instances of asking to to-go items that were delivered for in-store consumption.

The meeting point for our walking tour.

Regardless, I arrived just before the tour began. I always like to do a guided tour when it’s available in English. First, I like to get context for what I've already seen (for this reason, I tend to take the tour later in the week—I like to discover the cool things on my own, then figure out what they were as we walk past with the interpreter). The most valuable thing, though, tends to come in the last 30 seconds. Before handing off my tip, I always like to ask the guide something specific about places to go or see or eat. Most of the other tour members wanted to know about nightclubs. One particularly brazen group of Fins wanted to know the simplest place to find women of a certain profession. The guide ticked off a couple of streets quickly, as though it were a fairly common question.

Mine took her a bit longer to answer. Since the following day's forecast called for rain, I asked her for a good district with cafes for writing and hanging out—I told her I was a writer and I'd rather take a break and work than try to brave ugly weather.

After she ticked off a couple of cafes and I told her I’d already found all of those, she sent me on a more complex mission: a trip to the Golitsyn Lofts.

This would prove to be a highlight of my trip to St. Petersburg and Russia generally.

The complex is an old mansion once owned by a family of Decemberists and offered to Pushkin as a writing space. That’s cool enough for me, except that the modern iteration is a conglomerate of hip shops, cafes, bars and even a hostel. There are tattoo parlors, fashion shops operated personally by the designer, and a number of quirky crafters selling their goods, from buttons to belts. In the loft, I met a Russian-born, French-raised man who had started a wine bar and coffee shop. There, he sold Russian wines side-by-side with trendy French vintages in order to tell the story of Russia’s growing wine industry and the improving quality of product. The owner’s girlfriend hailed from Novosibirsk, so we spent some time talking about the city’s recent upswing in hipness while he tended to the steady flow of customers, most of whom were visual or performance artists with a sprinkling of musicians. The atmosphere and community in that place were incredible, and in addition to meeting some truly fascinating people, I was introduced to the music of Montreal-born chanteuse Klo Pelgag, who in the intervening weeks has become one of my favorite musical artists. I left, took a midnight stroll around the historic center of Petersburg, then headed back for some sleep.

Friday:

Friday included a trip to Finlandskaya rail station, the place where V. I. Lenin returned from exile during the onset of the Russian Revolution and began steering the Bolshevik party from Russian soil. Prior to that he had written and published from abroad, his texts often smuggled into the country and then read aloud at factories of other gatherings of workers. Lenin had ideas, and he had flaws. He’s viewed in a thousand degrees, with an odd blend of affection and blame. Regardless of your take on his theories and the government that sprang from them, I love to see the spaces on which history hinged: the places where powerful women and men changed the course of history. Even though the Finland stations was demolished and rebuilt—in boxy, column-laden stile with the requisite Lenin gesturing from the square that fronts the station, this is a place where history took an immense turn, and it felt powerful to be there. As a writer, too, I’m can’t help but be struck at home much the revolution was shaped by authors and thinkers who distributed their ideas broadly and often covertly through print. There is great power—for good, for evil, and for change generally—in a powerful and carefully composed text, and I was reminded of that while standing in the place where a writer became a tactile leader and changed a big portion of modern history.

Finlandskaya Station.

That wasn’t all I saw of Lenin on Friday. After some food and a quick stop back at the room to refresh, I took the metro to Moscovkaya Station and walked back toward the city. On the way, I stopped at another Lenin monument, where the current inhabitants weren’t worried about writing and the only thing revolutionary about them were the bright, mis-matched colors of their skateboard wheels. Across Russian, Lenin monuments (which tend to be in open, central squares) tend to be incredibly popular with skate kids. This one, in particular, was surrounded by an intricate system of ramps and guardrails that made for a blissful skatescape.

Further down the street, I strolled through Victory Park, where St. Petersburg residents had no qualms about stripping out of their work clothes and sunbathing in their underwear, beneath the watchful thousand-mile stares of busts representing the nation’s military heroes.

I arrived back on Nevsky prospect just in time to see the seemingly incessant traffic grind to a halt. Sensing this was unusual, I reached for my camera and waited. A few seconds later, a parade of tanks, troop carriers, and missile casings rolled down the street. They were on their way to the evening’s run-through for the Victory Day Parade, and so it was anything but sinister—still, watching a column of such power roll down a busy city street in mid-afternoon is enough to give anyone a neck full of goosebumps.

In the evening, I took in my second opera of the week, this time a shorter performance—just three hours. The performance, like Wednesday’s was spectacular. Unlike Wednesdays, I sat on the floor level, or the partir, where most of the crowd held their seats for the duration of the performance. Up in the cheap seats, it seemed like much of the crowd—Russian and foreign alike—were checking “Dressing up and Walking into Opera” off the list of things to do in St. Petersburg, and they started rolling out in droves once the first intermission hit. Down on the floor, though, the audience was invested and attentive, and the performance was amplified as a result. On the way out, more than 200 dressed-up opera-goers waited more than a half hour for the first bus to arrive outside the venue and start ushering us toward our homes and rented rooms. And while a few of them grew huffy toward the end, most calmly accepted the wait. It was a remarkable thing, though, to watch so many gowned and tuxedoed patrons waiting for city buses.

Saturday:

The deeper one walks into a Russian market, the more stripes the Adidas shoes gain. They were at a solid six by the midpoint of the market at Udelnaya, and the Nikes had sprouted shark-line fins on the swooshes. I saw an Ohio State University sweatshirt that was maize and gold—likely some combination of a hilarious joke, a translation problem, and a sketchy effort to skirt past copyright protection.

Just beyond the Alp-shaped tables of discarded shirt from Western charities—that's right, the stuff you pawn off on Goodwill is just as likely to wind up on sale in bulk at some Eastern European market stall as it is on a store rack in the States—there's a writer's gold mine. Part of the reason I love markets so much is that they do for present culture and society what museums do for expired civilizations: they provide a clear snapshot into what people's lives are, or what they very recently have been. And for a storyteller, these places are unmissably chock full of unanswered questions and the sort of curiosities that lead to the very best of stories. To wit: a blanket spread on the ground, over which an old man presides, sitting on a wood stool and propped up by a cane. The blanket is coated with the mundane things that can be gotten rid of for a few extra rubles of dinner money: yellowed, dog-eared books, a couple pieces of old clothing, spent and rusty tools, and some tableware. But then, in the very center of it all, is a giant, inexplicable disco ball. Wait, what? Nearby, a woman who appears to be a retired exotic dancer has her own blanket laid out, and her used costumes are selling with surprising briskness to younger girls and a couple of middle-aged women.

Inside the rented and covered stalls, one grizzled salesmen keeps all sort of old Soviet buttons and pins, something that's excessively common at the stalls, and probably the primary draw of foreigners. What sets him apart, though, is the merchandise that's jammed down into the displays: small but discernible edges of rusted swastikas poking out for those who care to let themelves linger that long. He has rusted helmets, too, behind the case, some with sickles and others with iron crosses. What's common among them, though, are the holes torn in the sides or tops of the metal gear. These weren't brought home by victorious solders at the war's end. These were collected off the ground, taken from those who didn't return at all.

One woman was selling nursing scrubs. Well, sort of. Half the nursing uniforms were, indeed, scrubs, and the other half looked like they belonged on the blanket with the other out-of-use dancer costumes—the sort of thing that might be found in an open-all-night store without windows. There are a number of solutions to what could have happened there—all of them amusing. Here's hoping no one went to the market and showed up to work in something pulled from the wrong end of that rack.

Pishki and coffee: the perfect afternoon snack.

In the afternoon, I went for a plate of sugared Pishki (Russian donuts) and a cup of Soviet-style coffee, with the sugar and milk stirred into the vat in which the coffee was brewed. I spent much of the rest of the afternoon revisiting some of the trip highlights, buying a new suitcase to help ferry my things back to the States from Novosibirsk, and checking out a couple of skate shops and quirky stores for souvenirs. By the evening, I was too worn out from a week’s worth of walking to get to worked up about going out, so I packed and prepared for the next day’s flight, took a relaxed evening stroll, and then headed to bed, tired but full of St. Petersburg’s wonder.

May 23, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #35.3: War Machines and Soft Power

Day two in Saint Petersburg was a packed one. In the morning, after free breakfast in the hotel, I grabbed coffee from the lobby of a business center near the Alexander column. I love the efficient way in which space is used in Russian cities; when you pass by a building and see a sign for a pastry shop, a coffee bar, a souvenir stand, a bar, or literally any other kind of business, it's just as likely you'll open the door and find that the business is a kiosk in front of a supermarket or next to the guard's stand of an office tower as it is to be a full room with seats and tables, or a complete shop with aisles. Later in the week, I would walk into a passage next to a shopping center (appropriately, the center itself was actually called “Passage”) which contained two coffee shops, a phone repair service, two DIY craft stands, including one where I found some amazing homemade buttons from carved and burned wood, a book shop, a bicycle repair station, and a juice bar. The space these businesses occupied had once been the management offices for the real mall next door—which was decidedly less interesting than its back corridor.

On Wednesday, though, it was Americano topped off with just a little cool milk (the barista's prerogative, not mine, but it was good nonetheless). Upon leaving, I began what would be a week-long dance with the local English-language walking tour. Upon visiting a major city for the first time, I always like the take the free walking tour (not really free, just tip-based, and my love of precision in language makes me wish they'd all just say this, though I'm sure the phrasing has something to do with cultural differences in the meaning of the word“tip.”) Even though I generally make it to all the sights covered in such tours on my own, I feel like there's something valuable about exploring with a community—even if it's just a ramshackle one formed of people who happened to roll out of bed on time that day. I also like to get spoken local context on the city's important places. Wednesday morning, I missed the tour's start by about ten minutes, which left me to wander.

I crossed the bank of the Neva River and headed to the Fortress of Saint Peter and Paul.

Church: the latest in a long string of things I seldom pay to enter, even when the basement has really historic catacombs.

The central feature of the island is an orthodox cathedral built in the European/catholic style. It's a gorgeous white thing with an epic steeple that makes its way onto most photo montages of the city, and I spent some time wandering around it and admiring the grounds. After being exhumed from nearly a hundred years in their hasty, shallow graves in a Yekaterinburg forest, the remains of Czar Nicholas II and his family (including Anastasia, who really did die, if you're prone to believing science over Disney) were moved there within the past decade, joining most of the rest of the Romanov dynasty in the church's catacombs.

[image error]

I was going to post a video of the the 1994 underground alternative hit "I am Anastasia" from Detroit grunge rockers Sponge, because the tragically underrated tune deserves to be played at every mention of the actual Anastasia. But this is what I found instead of the band's Web page: the little-known and oft-forgotten band has earned the distinction of "Limited Access". If you're on a continent that allows it, you should look up the song. It's great.

Years ago as I was preparing to visit Paris for the first time, a high school classmate who had traveled broadly during his time in the U.S. Air Force gave me some prescient advice. “There are plenty of free stairs in Paris,” he wrote me. “Never pay to walk up stairs. If you're smart, you can find the same view for free, and you don't have to live with the fact that you've paid money to do work. I've held on to that advice over the years, and expanded it in certain situations. In the case of Russia, I've generally expanded it to churches. There are plenty of churches to visit for free in order to see the shiny things inside. And if it's God you're after, I'm of the belief He'd rather you just talk to him where you are, rather than paying a fee to kneel in a certain spot and run through a certain set of motions. But that's me. Regardless, paying to enter a church isn't my thing, even if the church actually operates as a museum now, so the walk continued on. I took a hike on the beach that rings the island, just in time to be standing directly under the canon that marks noon—that was a loud bit of surprise.

I had lunch a Burger King.

Don't judge me. Here's the thing: there were plenty of sights to see in the nearby vicinity, and I didn't want to waste half a day searching for authentic local food that may or may not be good. So I grabbed a burger and got on with it. Here's the other thing, though: if fast food restaurants were to abide by the same rules the Russian government requires (KFC has to change its fry grease every 15 minutes, for example, instead of whenever they get around to it) or if they used fresh or interesting ingredients like they do in shops here, I might actually go to those places on purpose at home. At Burger King, I had a blue cheese burger with creamy pepper sauce and actual crisp bacon—not the limp, pale junk that so often populates the company's food in the States. McDonald's in Russia features a chicken curry sandwich that actually tastes like food. If only these companies would put the same effort into serving he people who made them rich instead of emerging markets they're trying to wedge themselves into, well, we might not see them as pariahs. Also, we might not all be teetering on the cliff of obesity.

After my fast food stop, I visited the Museum of Russian Artillery. I followed my policy again about paying to see things, and I feel this museum suffers a bit from its own hand: all the cool stuff is outside. I'm sure there were great exhibits inside, too, but when you put all the tanks and rocket launchers in the courtyard

and let people roam them for free, there's not much incentive for the casual visitor to come inside and read plaques about the inventors of the awesome stuff that's outside.

Let's just assume whomever designed this tank also drove a red convertible.

At this point, it was time to head back toward the hotel and begin preparing for the evening. I'd made reservations to Jamie Oliver's first Russian restaurant, after which I had tickets for a five-hour-long Russian opera.

The food was outstanding. Russia has given me an appreciation for beef carpaccio, something I’d never tried before or particularly cared to. That was a starter, followed by a perfectly cooked steak with fresh, local mushrooms, garlic sauce, and arugula. The restaurant was gorgeous, and even when it was half-filled, reservations were required. Most of the patrons were dressed as though they were at the beginning of an occasion. And then…clustered together in a corner the waiter called the “tourist section,” were a cluster of westerners in T-shirts and sweatpants, mostly talking loudly and complaining about everything—or making fun of the servers or other patrons who they apparently imagined couldn’t understand English.

By virtue of my reservation in English, I too was set for that section until the hostess, on behalf of my opera suit, upgraded me to the rest of the restaurant.

Dress how you want, I guess—although I have to believe that someone with the means to complete a months-long visa process, travel halfway across the globe, and intentionally book a table at a nice restaurant probably has access to grown-up clothes. But the words, the crassness, the smugness, but harshness—all of it unnecessary and unprovoked—that’s what got me. I don’t think anyone really cares if Americans roam the globe in fleece sweats, but when encountering some travelers, I sometimes fear that our culture gets represented chiefly by two groups: the most ambitious and the most caring, or the rudest and most selfish. The average, typical, everyday American seldom shows up in far-flung places, and so when we hear accounts of foreigners either “loving us or hating us,” I wonder deeply if it correlates with the sometimes too-binary group of us that travels. I know that one my worst days, I can fall into that wrong group. That’s something I’ve tried desperately hard to avoid on this trip. I’ve have numerous encounters in which people told me I was the first American they’d met. If I’m in a crummy mood and turn that in their direction, then they’re going to keep that interaction with them. In the end, it doesn’t matter if I’ve got on pajamas or an opera suit: the way I’m perceived comes down to the way I treat other humans.

Food: it tastes great no matter what you're wearing, but it's best served with a side of general human decency.

Everyone has bad days, and I’ve had a few on this trip. But moments like that meal—situations in which I’m in a larger city and able to observe larger groups of tourists—makes me even more conscious of the way I act around others and the impact in can leave, of the benefit or damage I can leave behind in just a few moments or even seconds. Beyond teaching and writing responsibilities, it’s begun to dawn on my that simply walking around and being human has probably been the most lasting legacy I’ll leave via this program, and I hope that I’ve done well, no matter which section of the restaurant I was in.

Fulbright Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the U.S. Department of State or the Fulbright Program.

May 10, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #35.2: St. Petersburg Travel Log, Day One

The taxi driver who picked me up at 4 a.m. recognized me from our last silly-early ride, and he shook his head. I know, I told him. I know. The airport schedules tend to carry an hourglass shape, and I’ve had my share of early morning and late night flights. This Tuesday morning trip was the busiest I've seen the airport at any time of the day: three departures were set for Moscow in addition to mine, bound for St. Petersburg. Everyone was tired. No one wanted to be there that early. But the consolation prize for everyone in that terminal was that within a few hours, we would be walking the streets of one of the world's greatest cities.

The schedule makes a bit of sense in light of the time difference: it's a four hour flight and a four hour gain to each of the country's leading cities, so persons of business can hop a morning flight and get to the city in time for a day of meetings or sales or whatever it is that business people still travel for—whatever shred of their work can't now be done online. I slept most of the flight, something I've gotten better at through the litany of sleeping-hours flights in Russia. It took a minute to shake off the sleep when we landed, but by the time I grabbed my suitcase, I was focused and ready to go.

From the baggage claim, I knew I needed a bus to the Moskovsky Metro Stop, then I'd make one switch at the Technological University. When I de-bussed and headed into the underground, my first stop was the transport card machine. St. Petersburg's aren't the most simple to use: you can't buy a pre-loaded card and must first purchase the card, then swipe it back into the machine to add value. Lots of tour guides and travel manuals advise against pre-buying a card in Russia since the discount is small, but it's not the discount that matters to me: it's the saved time and hassle of having to stand in line at the token machine—plus, I'm always invested in fitting in. I've found that when I’m traveling overseas, the best way to avoid unnecessary pat-downs and subway bag screenings is to seem like you belong. Russian police in particular have no concern with the concept of profiling; if you appear foreign, you'll get twice the scrutiny—period. That's just how it is, for better or worse. So the more prepared and local one seems, the less likely they are to be stopped over and over again.

The Saint Petersburg Riverfront.

That was the idea, at least. It's worked everywhere else, but in St. Petersburg where authorities are understandably taking heightened levels of care, my pat-down rate was about to resemble Aleksandr Karelan's career record, despite my best precautions. By the end of the trip, I simply started walking straight toward the X-ray scanner outside the turn styles. The thing is, if feels like an inconvenience the first time or two, but it’s quick, it’s painless, and the attendants are generally cheery. In the lines, I saw plenty of people getting grumpy toward the security folks, but it accomplished nothing and served only to leave the tourists griping and complaining long after they’d headed down the escalator and toward the trains. But a week-long trip to one of the world’s most beautiful cities leaves no time or reason for that kind of unnecessary angst, so I just smiled, let them check my computer, and went onward. Easy enough.

My bag and I did finally get through the Metro—but Google maps had kindly sent me to the wrong hotel, though the names were amusingly similar. I'd intended to walk around the city upon arriving, but hadn't planned on doing it with my luggage in tow. I'd put in a good two miles of hiking before I finally made it to the hotel, where I deposited my things and took off to explore, unburdened of much of my load. First stop: breakfast, which is not typically my favorite meal, but a made-to-order cafeteria chain called Marketplace provided the right combination of ease and tasty, plus it gave me a chance to recalibrate and plan. It was just 8 a.m. local time at this point, and check-in wouldn't start until 3 p.m., so I had time to explore.

I checked in on top-rated coffee shops and encountered a problem that would hound me all week—and one that led me to want to write a full-blown St. Petersburg Travel Log. Namely: most people who visit St. Petersburg seem to do and write about the same dozen things and eat and review the same dozen restaurants. And I wasn't having it.

A lot of foreigners visit St. Petersburg. Cruise line companies have even worked out a scheme that allows visitors to enter the country visa-free—provided they arrive by cruise ship, stay outfitted in badges the entire time, and stay in approved hotels, take official (and overpriced transportation into the city, and eat at approved restaurants. Aside from a new pilot program in the far East (one I very much plan to take advantage of in the future), this is the only way and place to enter Russia without navigating the difficult and nerve-racking visa scheme. There were so many foreigners, in fact, that my hike away from Marketplace left me with one distinct observation: the best way to tell the difference between Chinese visitors to Russian and Westerners is that the westerners tend to be dressed in track pants and sharing renditions of the unspeakable things they did after last night's seventh pint, while the Chinese are in trim business wear, carrying portfolios full of documents that are undoubtedly shaping the future of geopolitical economics. It's not a good look on us, fellow Westerners—not a good look at all.

One of the first things I tend to search upon visiting new cities are Off the Beaten Path reviews. The first one I read for St. Petersburg suggested that visitors, as an alternative to the normal activities, head to the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood. This is not off any beaten path. In fact it’s one of the city’s most recognizable places, one constantly ringed with tourists, cameras, street vendors, and buskers. When I saw this was as far as anyone had gotten in labeling the unusual sights of the city, I knew I was in for some good exploration. I also knew I wasn’t going to be able to count on much expert guidance.

Sampling the merchandise at Coffee 22.

The first place I chanced past was tucked into a side street near the Griboyedov Canal. Coffee 22, named after its address, turned out to be brilliant. To the extent that I saw what other folks were eating, I instantly regretted having already eaten breakfast. But the coffee was good enough (I had a light, locally coasted Kenyan filtered through a Hario V-60), and the music was top notch: the defining feature of the place is a two-turntable DJ deck in the middle of the room, where someone was spinning even at 9 a.m. The owner, who brought my coffee, said music and rhythm dominate the human experience, and that he wanted to build a sonic atmosphere that accentuated his product. During my visit, the sounds bobbed seamlessly from American soul to European ambient and back. To top it all off, the plentiful outlets for some post-flight recharging were brilliant aides. As it tuned out, all my devices—from a three-month-old phone to a six-year-old computer—decided to lose half of their battery life this week. That led me to spend most of the trip with my phone off, which was actually a godsend. Given that so few of the interesting stops had been reviewed or suggested by anyone findable, I turned out to have much better fortune aimlessly wondering around and walking in places that looked interesting.

And it actually worked. This is a bigger generalization than I'm normally comfortable making, but I've found that in Russia, the quality of the food/drink/entertainment/clothes/whatever tends to closely match the external design. Folks here who care about their products tend to be incredibly thoughtful about every inch of he process: the image, the marketing, the style, the atmosphere. I've found that if a place looks halfhearted, everything about it tends to be halfhearted, and if a place look purposeful and well put-together, the contents are likely to match. I'm sure there are exceptions, but I have yet to find a bland-looking restaurant building with exciting contents, and visa-versa. If a place looks hip, it will probably taste that way. If a place looks soviet or divey or chainy and bland, the contents will likely match. It's a pronounced consistency here, and so it's generally pretty easy to tell what you're going to get before entering a place.

Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood as seen from the canal.

From coffee, I headed for the canals. St. Petersburg was originally a swamp, drained and back-filled with earth, and there are all sorts of stories and legends about emperors demanding that visitors to the fledgling city bring rocks along to help with construction. Now, the land is solid, but the city is ringed by canals and crisscrossed by rivers, lending to the nickname, Venice of the North. There’s not much else particularly Venetian about the city, but I’m sure the nickname works as a marketing tool. The ever-present water, though, gives the city an attitude of flow: everything seems to me moving and shifting.

For all the dozens of times I walked past it, I never went inside the Hermitage. For all my curiosity, I've never been a huge connoisseur of museums. When I do go in them, my text-focused mind tends to spend all day reading the placards and little time actually watching the exhibits, and so to be frank, the heart of the experience is largely lost on me.

The Hermitage, which I walked past a dozen times but did not visit.

I bet it's amazing inside. But I've seen the interiors of palaces before, and I've seen the works of European master artists, too. With just four days to spend in St. Petersburg, the museum didn't get to claim one. I visited the square, though and watched military bands play in rotation. Somehow, a pair of tourists managed to miss the whole mass of people in uniform and their exceptional amount of noise, and found themselves stuck walking between columns of marching instrumentalists. That, folks, is awkward.

After grabbing a burger for lunch, I walked the Neva River embankment, then headed back to settle in to the hotel. From there, I did an unusual think: I left my laptop locked up in the room and traveled light, with just my phone and camera. I spent the rest of the afternoon walking aimlessly, not particularly looking for anyplace to go, but simply looking. The ornate imperial buildings, interspersed between grey flats from one Soviet era and brightly colored soviet flats from another, were as diverse as they were unending.

By the time the sun fell and I headed back to the room, my phone had me down for almost twenty miles of walking, and as soon as I sat, I felt every inch of it in my ankles, knees, and hips. I spent a couple entirely un-exciting hours on work—creative and otherwise—before turning in for the night. It felt like I’d crammed half a week into the day, but that’s how I like to travel. Tomorrow, I’ll pick up with Wednesday’s adventure, including three different eras of history and tips for surviving a five-hour-long Russian opera.

The views expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State.

May 5, 2017

Dispatches From Siberia #35.1: Greetings From St. Petersburg

I'm on the road this week, visiting the incredible, vast, and sometimes confusing city of St. Petersburg. This place is and has a little bit of everything, and I'm busy exploring it, squeezing every milliliter I can from each of my five days in town. Because of that, this week's blog is short, but have no fear: there'll be a mid-week sequel once I get back to Novosibirsk. Part of the reason for that is that I realized yesterday that for all the different sorts of writing I've engaged in, I've never written a full-blown travel log. I want to do that for St. Petersburg--tell the story of the trip from beginning to end--and I'll do that once I return to my flat and have a moment to digest what I've seen, heard, felt, and tasted.

This couple clearly took a wrong turn while walking through St. Petersburg's Palace Square.

In the meantime, there's some sad news. I have to take a moment here to offer an elegy for a trusted long-time travel companion that passed on yesterday. My white, in-ear Sennheiser headphones finally gave up on life, somewhere along Moscovskaya Ulitsa. Don't laugh: this is serious business. See, I obtained that particular set of headphones during the first week of my trip to Ireland in 2010. First of all, I want to point out that I went seven years without losing something as small as a pair of headphones. That impresses me deeply, and bodes well for my potential future success and happiness. I cannot say the same thing--at all--about any pair of sunglasses that I've owned, ever. That trip to Ireland, a travel grant through the Southern Illinois University Department of Irish and Irish Immigration Studies, was my first trip abroad. After discovering on the flight over how cumbersome and generally irritating were the over-ear models that I'd brought from home, I picked up the Sennies from the discount bin at an Irish electronics store. Over the next seven years, they would travel the globe with me, an always present companion. Music, podcasts, videos, lousy airplane movies, Skype conversations to loved ones back home: they were my number one tool.

Me circa 2010 in Galway, Ireland with a pair of then-new Sennheiser headphones. The headphones passed away this week at the age of seven.

Those headphones made it to Prague five times and Paris Twice, Dublin countless times, and Moscow half a dozen. They've been through Ukraine and Sarajevo. They were on my head when Trans-Dniestrian separatists tried unsuccessfully to hijack the marshrutka bus I was taking through Moldova, and they were on again a bus driver tried unsuccessfully to drop me off on a deserted roadside at the Romanian border--at three in the morning.

I hiked with them back and forth between my rented room and the city center of Galway Ireland, the first place where I lived overseas, and I used them to listen to music while I feverishly wrote in my apartment at the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France, where I finished two books that will be published later this year. And I used them to avoid whatever madness was happening around me in the often wild-west-felling public transit systems of Russia. I wore them while walking on the frozen Baltic Sea in Sweden, and they were in my bag when I drove on the autobahn.

I plugged them into my iPad and listened to happy songs, trying not to cry as I waited for my plane last November after seeing my new fiancee off to her own flight in an opposite direction, portending six more months apart before we would have the chance to start our lives together in earnest. And it's just that anticipation, so close now--just a few weeks--that makes the loss of an otherwise silly object like headphones particularly poignant this week. See, after almost a decade of traveling the world largely alone--a pursuit in which a pair of good headphones is an unquestioned best friend--St. Petersburg is the last major city I'll visit as a solo traveller. After our July wedding, I'll have a permanent travel companion, and less use for all the things headphones can accomplish. That little strand of always-tangled cord and the plastic nubs I jammed into my ears so many thousands of times reached the end of their function and their importance at the same time. Fare thee well, sweet Sennheisers. You did good work, and you'll be remembers. Also, you'll be replaced with more Sennheisers, because a pair of headphones that lasts seven years is just an amazing, amazing thing.

By the middle of next week, I'll have a full rundown of St. Petersburg, including observations on the ways in which tourists make fools of themselves, the problems of visiting a city that travel writers have done their best to turn into a cliche, the glory of Russian opera, and overcoming public transit that goes no place travelers want to get, and everyplace they don't.

Until then, be comforted by the official Fulbright Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are my own and do not represent the United States Department of State or the Fulbright Program.