Peter Cawdron's Blog, page 15

December 7, 2013

Black Friday Has Nothing on This Bookish Gift Guide

Reblogged from Books and Bowel Movements:

Reblogged from Books and Bowel Movements:

Mugs & Shiz for Readers

Top Left | Caution: Hot. And Literate Mug @ Harvard Book Store ($9.99)

Top Second Column | Write Like a Motherfucker Coffee Mug @ Rumpus ($13)

Top Third Column | Penguin Classics Logo Mug @ Penguin ($11.95)

Top Right | Peace. Love. Books. Mug @ Malaprop's ($14.50)

Middle Left | Alice in Wonderland Literary Transport Mug…

Christmas presents for the book lover in your life :)

The joy of reading

We have a beagle called Charlie. He’s a beautiful dog, but he’s convinced the world needs to be explored by taste and will chew anything in reach — shoes, books (including those still in a parcel from Amazon), CDs, toilet paper, TV cables, socks, chair legs, and the list goes on. He’s worse than a toddler!

We have a beagle called Charlie. He’s a beautiful dog, but he’s convinced the world needs to be explored by taste and will chew anything in reach — shoes, books (including those still in a parcel from Amazon), CDs, toilet paper, TV cables, socks, chair legs, and the list goes on. He’s worse than a toddler!

Needless to say, we’ve been working with Charlie on this and we’ve discovered a pattern. If he’s bored, he chews. Keep his mind stimulated and entertained and he’s quite content and charming between times. Neglect him, and it’s Go Dog Go!

And this raises an interesting point about intelligence. We humans need to be entertained. I suspect this is why reading fiction holds such an appeal to intelligent people.

Think about recent books that have captured the imagination of readers: the Harry Potter series, Game of Thrones, even the Twilight series, etc. They all have one thing in common. They lift people up from this world and whisk them away. Our minds thrive on imagination, regardless of how frivolous such fiction may be. And although it’s somewhat surprising and counterintuitive, such nonsense is invigorating and refreshing.

Intelligence thrives in an active mind, and imagination is the key to activating the mind. Reading fiction, it seems, is a catalyst for good thinking.

At the risk of being subject to a confirmation bias, I’d like to suggest that reading correlates with intelligence. I’m not sure which is cause and which is effect, perhaps they both serve in equal measures. But reading fiction opens vistas of the mind, and expands our intelligence. We may not chew socks or drag toilet paper around the house, but without such mental exercise, we grow stale and atrophy.

Reading is a chance to see the world through the eyes of another, and that change of perspective enlightens and informs, builds empathy and allows us to grow beyond ourselves. For me, that’s the joy of reading, having the chance to learn and grow.

Here’s a sample of Little Green Men as an audiobook, it’s frivolous but fun, and great for listening to while commuting.

This Christmas, I’m releasing a fan-fiction work called Shadows set in Hugh Howey’s Wool universe on Kindle Worlds, and a thriller called The Man Who Remembered Today.

If you’d like to enter a draw for free copies of these works, sign up on the mailing list.

Merry Christmas

Happy Hanukkah

Frivolous Festivus

December 1, 2013

What is life? (Spoiler alert: nobody knows)

“Just as the colors of a rainbow merge imperceptibly one into another, the transition to life from nonlife is a seamless continuum”

J.W. Schopf

I teach a variety of classes at my university, General Biology for science majors, my own Pharmacology course for undergraduates and from time to time I also teach graduate courses in my own area (Biochemical Pharmacology and Neurobiology) among others.

Life... the final frontier...

November 28, 2013

Sungrazer

This Thanksgiving, Comet ISON is heading for a close encounter with the Sun.

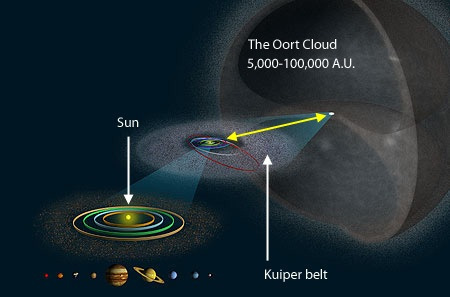

Comet ISON originated in the Oort Cloud, a gravitationally bound “cloud” of far-flung icy debris left over from the formation of the Solar System some 4.5 billion years ago.

The Oort cloud orbits the Sun but at the phenomenal distance of a light-year away or more. When you stop and consider that the Voyager spacecraft isn’t even a light-day away from Earth, you get an idea just how vast our Solar System is and how tenacious the Sun’s gravity is on distant objects in the Oort Cloud.

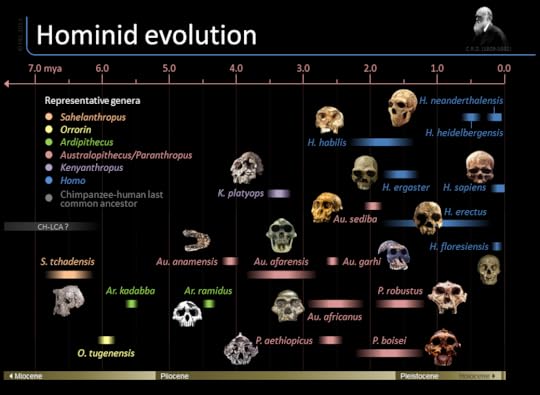

Although this is undoubtedly Comet ISON’s first encounter with the Sun, the comet’s orbit has been estimated at a staggering 400,000 years. ISON started its long, slow fall toward the Sun when Homo sapiens still shared the planet with Homo neanderthals and a bunch of other hominids!

If ISON survives its encounter with the Sun, it may eventually escape our Solar System altogether so this could be the only time this comet is ever visible from Earth.

In this animated GIF, you can see a huge coronal mass ejection (CME) coming out from the Sun (with the sun blotted out in the middle of the image to protect the camera optics). At the same time, ISON approaches from the right.

Although the sheer size of the CME dwarfs the comet (and Earth for that matter), this need not spell doom for the comet as we’re seeing a 2D image of a 3D event covering a vast region of space.

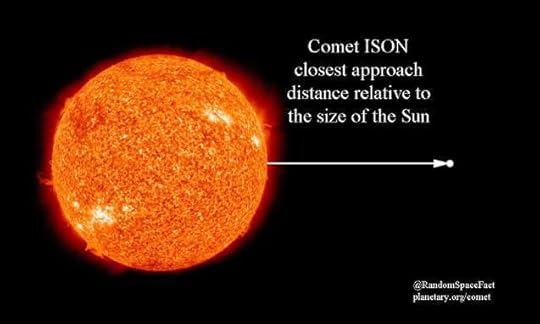

Most astronomers suspect comet ISON will break up and disintegrate while rounding the Sun. At its closest approach the comet will be just over a million kilometres away from the surface of the Sun (725,000 miles or barely three times the distance to the Moon).

ISON is called a sungrazer because it’s going to approach to within roughly 1% of the distance between Earth and the Sun. ISON is well inside the orbit of Mercury (at anywhere from 29 million to 43 million miles from the Sun) and is travelling at up to 360 kilometres per second (roughly 224 miles per second). At that speed, ISON travels the length of the Continental US in fifteen seconds, that’s over a million kilometres an hour (800,000 miles an hour)!

At its closest approach, comet ISON will be subject to temperatures around 2700 C (almost 5000F), causing the outer layer of the comet to boil away at an astonishing pace.

Rather than being a lump of solid ice, comet ISON probably has a consistency closer to packed snow or an ice-cream sundae. Being 2 kilometres wide (roughly 1.2 miles), it would make for one hell of a snow cone!

At the moment, ISON is too close to the Sun to see without damaging your eyes. If comet ISON survives Thanksgiving, December will give rise to possibly the most spectacular comet ever seen from Earth.

Happy Thanksgiving!

October 19, 2013

Spoilers won’t spoil Gravity

Gravity is a thoroughly enjoyable science fiction survival movie with a refreshing amount of attention paid to the finer details, and some wonderful depictions of weightlessness.

Although Gravity has been subject to criticism by everyone from Phil Plat (the bad astronomer) to Neil deGrasse Tyson because of the liberties taken with orbital mechanics, it’s important to realize that they and all the other critics still LOVED this movie. It seems the Gravity is a movie you can’t spoil.

Even knowing the faux-pas didn’t deter me from seeing Gravity on the big screen in 3D this weekend. If anything, knowing about these issues in advance (many of which are evident in the numerous trailers) allowed me to enjoy the movie all the more.

The issues that seem to be raising the ire of some are largely forgivable. They hinge on:

MMU (the jet-pack like manned manoeuvring unit used by George Clooney) has very limited fuel. MMUs are the NASA equivalent of a bicycle and could not be used for long-range travel as they are in the movie, although to their credit, the writers cover off on this by saying George has a long-duration prototype.

Distances and relative speeds are compressed for the sake of storytelling. Communications satellites orbit at 22,000 miles so as to be geostationary, not the 220 odd miles depicted in the film

The debris field produced by a chain reaction of satellites exploding s.t.r.e.t.c.h.s. credibility. Such a chain reaction isn’t possible, and if it did occur the debris cloud would not cluster together at one altitude (a lot depends on what kind of chain reaction “explosion” we’re talking about)

Velocities are interesting to consider. A satellite in orbit at at the same altitude as the International Space Station is going to be traveling at 17,000MPH. If it’s struck by a missile with something similar to C4 as an explosive, the shrapnel generated by the explosion will be accelerated by up to 20,000MPH in all directions. Some of it will fall back to Earth. Some of it will be accelerated beyond the escape velocity for an Earth orbit (which is roughly 25,000MPH) and will enter an orbit around the Sun. The rest will enter all sorts of weird and wacky, highly eccentric orbits in between. It’s going to be a mess, but it’s going to be a far-flung mess.

Hubble, the International Space Station and the Chinese Space Station are all in entirely different orbits, not just in terms of altitude but inclination. This may not seem like a big deal, but moving between such disparate orbits is hideously fuel-expensive, so much so it’s often easier/cheaper to launch separate missions than to go flitting around between them in orbit!

Debris (and people) won’t fall away toward Earth when something catastrophic happens (Newton nailed this five hundred years ago)

When our astronauts are tangled in the parachute cord and the tension is reached on the tether, pulling the line taut, both Sandra Bullock and George Clooney would have rebounded back toward the space station without the need to do anything. Their reaction would be much like a yoyo on a string.

Space is not flat. Although someone might appear to be “floating in zero gravity” the reality is their motion (and any change in their orbit) is more akin to NASCARs racing around a steep bank

Orbital mechanics is a lot like NASCARs driving around a banked track. There’s no such thing as zero gravity, only a blisteringly fast freefall in a gravity well. Changes in orbits work much the same way as changes on a sloping track, with different speeds positioning the cars at different heights.

But for all that, there is an astonishing amount of detail Gravity gets right, from the interior of the International Space Station, to the cramped, claustrophobic cockpit of the Soyuz and the sweeping vistas of Earth as seen from a low orbit.

Charles Simonyi has been on board the International Space Station on two occasions, both times traveling to and from the station in a Soyuz. He made the following observations about the movie Gravity.

Charles Simonyi oversaw the development of Microsoft Office before becoming a space tourist

I’ve also heard from other astronauts that they liked the way Sandra Bullock complied with the first rule of a space flight emergency: RTFM – Read the @#$ing manual.

Thankfully, she has a copy of Soyuz-for-Dummies as there’s no iOS or Ice Cream Sandwich on this vintage spacecraft

Look at how perilously thin the atmosphere is… if Earth were the size of a basketball the bulk of our atmosphere would be no thicker than a single sheet of plastic Saran-wrap

Considerable care has gone into replicating the inside the International Space Station

Even though the orbital maneuvers were oversimplified, Buzz Aldrin loved Gravity because it gets so much right and awakens our sense of awe for space flight. Sure, there’s some nitpicking on the physics, but the vast majority of details are astonishingly precise and incredibly well portrayed.

Five stars from me.

September 23, 2013

Panspermia

Panspermia sounds like science fiction, but it is a serious scientific theory that seeks to examine if life on Earth arose from outer space.

According to the Oxford dictionary:

Panspermia is the theory that life on the earth originated from micro-organisms or chemical precursors of life present in outer space and able to initiate life on reaching a suitable environment.

There are three possibilities when it comes to panspermia

Life arose on Earth independent of any influence from space

The building blocks of life arrived from space

Life arrived from space

Let’s examine each of these possibilities

Life arose on Earth independent of any influence from space

Artist’s impression of a baby star still surrounded by a protoplanetary disc

Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

This first possibility is pretty quickly dismissed by everyone other than creationists.

Earth is not special in a cosmological sense. Earth is not a separate entity somehow set apart from the universe, it is a miniscule part of the universe.

Earth is comprised of debris from space, having been formed as part of the accretion disk that swirled around a newly born star we’ve conveniently named the Sun.

The Sun (and consequently Earth) are second-generation celestial objects. Apart from hydrogen and possibly some trace parts of helium and lithium formed in the Big Bang, every other atom in every single molecule on Earth originated in the fiery heart of a previous generation of stars.

Life arose on a planet that was the result of natural processes in the depths of space, so in some way, panspermia played a part.

The building blocks of life arrived from space

Comet Hits New York City

Credit: Sandia National Laboratories

The use of the term “precursor” in the definition of panspermia makes the concept quite broad. In other words, Earth need not be “seeded with life” (either deliberately or via happenstance), it could simply be that the emergence of life was facilitated by the arrival of celestial ingredients on comets and meteorites.

This might sound far fetched at first, but it’s actually quite plausible when you consider that during the Late Heavy Bombardment our planet was inundated with…

20,000+ impacts leaving craters over 12 miles in diameter (20 km)

40 impacts leaving craters 600 miles wide (1000km)

several basins over 3000 miles wide (5000km+)

Earth’s oceans, as an example, probably originated from water-bearing asteroids arriving during this period.

There are vast clouds of pre-organic molecules in absurd abundance in space. Glycine – CH2NH2COOH – is the simplest of the 20 amino acids that make up our bodies, and it can be found in mind-bogglingly huge molecular clouds in Sagittarius B2 (spanning 150 light years) and the Orion nebula (spanning 24 light years and estimated to contain 2000 times the mass of our Sun).

We know of comets that have originated from outside our solar system, meaning they’re not comprised of the material that coalesced into the Sun and planets, raising the possibility of trans-stellar panspermia from molecular clouds such as those we see in Sagittarius and Orion.

In addition to this, comets need not have deposited life or even the building blocks of life on Earth, as research has revealed that the intense pressures and temperatures that occur during an impact can give rise to the building blocks of RNA.

…models predicted that an oblique impact could give rise to nitrogen-containing hydrocarbon rings, the major structural component of RNA’s nitrogenous bases… more violent collisions could power the creation of long-chain carbon molecules like those that form the backbone of many amino acids…

Experiments have also shown that the conditions experienced in deep space allow for the natural formation “dipeptides – linked pairs of amino acids.” Space, it seems, is a veritable play-pit full of the Lego blocks required to build life.

During the Late Heavy Bombardment, upwards of a hundred million tons of precursor material arrived every year!

Life itself arose from space

Tardigrades survived for 10 days unprotected in space

Credit: Getty Images

We know life can survive in space. Micro-animals such as Tardigrades (water bears) have been revived after spending ten days in the vacuum of space, while lichen has survived for 18 months on the outside of the space station.

As impressive as this seems, life would have to survive for millions to hundreds of millions of years for panspermia to directly seed life on Earth, making this form of panspermia unlikely but not impossible.

An experiment at the University of Kent has shown a small percentage of algae can survive an impact at 6.93 kilometers per second.

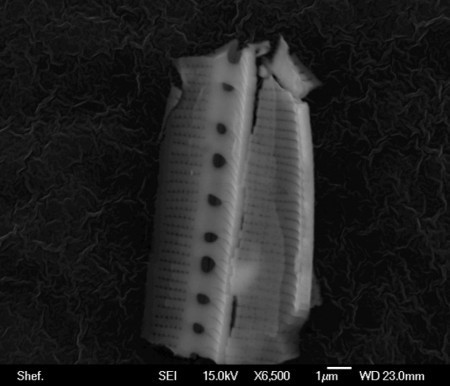

Scanning electron microscope image of the diatom frustule

Just last week, researchers at the University of Sheffield announced they’d collected atmospheric samples from the stratosphere above England. To their surprise, they found the damaged remains of what looks remarkably like a diatom, a form of algae.

Skeptics have suggested the diatom could be a contaminant from the balloon or from lower in the atmosphere, but the controls seem genuine.

The experiment needs to be independently repeated, as if this finding is correct, then Earth is being continually “seeded” and has been for billions of years. Although this seems highly unlikely, it wouldn’t be the first time science has turned out to be stranger than science fiction.

To put this experiment in context, the collection was conducted at 22-27 km above Earth’s surface (70,000 to 88,000 ft). Commercial airliners fly at roughly 9 km or 30,000 ft.

The following image is of a high-altitude balloon bursting at roughly 33 km, giving you a good idea of just how far up this collection occurred.

High-altitude balloon bursts at 33km

Credit: Slaros project

Panspermia is a fascinating concept, and one that continues to gather more interest and more research.

September 6, 2013

Short sighted

Myopia is the medical term for being short sighted, where someone can see those things immediately before them with clarity and yet distant objects appear blurred.

Humanity has struggled with mental myopia for thousands of years.

It’s natural to think we have 20:20 vision, but we only see a fragment of reality. Take for example the concept of sunrise and sunset. Almost five hundred years have passed since the Copernican Revolution, when an obscure Polish astronomer developed a mathematical model to describe the orbit of the planets, placing the sun at the center of the solar system.

What made Copernicus notable, wasn’t his theory, it was how he derived his theory. His calculations were no less complex than those of Ptolemy and his Earth-centric view of the universe, but the model proposed by Copernicus required less assumptions and naturally explained key points, like why Mercury and Venus never strayed far from the Sun.

In this Ptolemaic representation, Earth is at the center, with the first orbit occupied by Luna (the Moon), the second by Mercury, the third by Venus, and the forth by Sol (the Sun). Copernicus realized numerous inconsistencies with this model could be resolved by considering the Sun as the center of the solar system.

The Copernican Revolution was the triumph of reason over the senses. For the first time, logical inference was more important than casual observations. To this day, we still speak of sunrise and sunset even though no such event ever occurs: Earth turns. Our senses tell us we’re stationary and that it’s the sun that moves during the course of a day, but we’ve learned not to trust our senses. We trust the scientific description of reality over what we see.

Regardless of whether we’re looking at stars in the sky or birds in a tree, we don’t see reality for what it is, we see but a snapshot in time, just a thin sliver of reality, a fragment of a larger story.

Look out at the stars and you’re looking back in time.

What were you doing eight years ago? Where were you living? How old were your kids (if you have any)? What job did you have eight years ago? Because, walk outside tonight and stare up at the sky and chances are the brightest star you will see is Sirius, and the light that falls on your eyes left Sirius eight years ago.

Out of the top 100 brightest stars in the evening sky, 80 of them are over 60 light years away, meaning the light we see from them is older than the majority of people reading this post. Catch a glimpse of Andromeda, and you’re seeing light that originate well over a million years before Homo sapiens arose as a species, and yet the view seems so sedate, so rudimentary, so commonplace and unassuming.

Like someone with myopia, we think we see clearly, but without science we only ever see a fleeting glimpse of reality, an oversimplification.

Another example of mental myopia can be found in creationism.

Creationists think of species as being formed independent of each other over just a couple of days, a few thousand years ago. In reality, every species we see is an extension of the most ancient forms of life branching out in endlessly varied forms. We tend to think of species as fixed, settled, but they are plastic and malleable, constantly adapting for a variety of natural reasons.

Biological life is in a constant state of flux, adapting and evolving before us, but at a rate that makes the motion of a glacier seem like a bush fire racing across a grassy plain. The animals we see today are simply the latest forms, not the final forms of life on Earth.

Creationist often ask, “If evolution is true, show me the transition species. Show me the missing links.” But the question fails to realize that every species is in transition, including our own.

It’s no wonder creationists think this way, as we naturally have mental myopia. With our five senses, we observe just the fleeting fragment of the vast reality before us, missing the depth of all that transpired over billions of years to bring us to this point.

As for, “Show me the missing links,” stop and think about that for a moment. How far back can you trace your family tree? Can you reach back as far as the Declaration of Independence? How about the reign of Elizabeth the First, or Julius Ceasar? Show me your missing links, prove to me that you really are a member of the human race and not the pedigree of some alien replicant sleeper cell. I’m being silly, but you get the point. The proof lies in that you’re here. To get here, you must have an unbroken chain of parentage, one that spans back not hundreds or even thousands of years, not millions or even hundreds of millions of years, but billions of years.

In theory, there could be a species alive today for which there is no fossil evidence at all (I don’t know of one, but it’s possible), and yet that this species exists tells us there is an unbroken lineage, whether we see it or not. That we don’t see it says more about our lack of vision than it does about that species’ pedigree.

Whether we are considering quarks or electrons, viruses or bacteria, whether we are looking out into the furthest reaches of space or at animals in a zoo, science has allowed us to see reality for what it is, exposing the hidden depth behind what we see with our eyes.

Science isn’t perfect, but it is self-correcting, providing us with a clear lense with which to see the universe.

The challenge that faces humanity moving into the future is to avoid being short-sighted.

August 31, 2013

Little Green Men

As far as we know, there are no “little green men,” which is what makes them the ideal subject for my latest science fiction story: What if, against all probability, someone ran into our fabled little green men on some remote planet?

And no, not the sort of LGM you find in Toy Story, I mean the vicious tropes found in the classic science fiction of the 50s and 60s.

Some of the earliest uses of the term “little green men” come from the 1900s, when they were used to describe supernatural beings and “cloudland fairies.” Rudyard Kipling described gremlins as little green men in his 1906 novel Puck of Pook’s Hill, but it’s the association with extraterrestrial (and presumably intelligent) creatures that defines the modern imagery behind the concept of little green men.

In 1967, mysterious radio signals were picked up from deep space and jokingly referred to as LGM-1. The regularly repeating signal turned out to be from a natural source, a pulsar, a highly magnetized spinning neutron star emitting a beam of electromagnetic radiation in much the same way as a lighthouse does. But this light-hearted reference to Little Green Men highlights our cultural fascination with the prospect of contacting intelligent extraterrestrial beings.

Being a fan of the quirky science fiction stories of Philip K. Dick, I’ve penned a novella called Little Green Men that looks at the impossible scenario of finding these archetype aliens on another world. As is my want, the story mixes fact and fiction in a thrilling encounter that would not be out of place in The Twilight Zone.

As much as I would have loved to use this brilliant cover design by Jason Gurley, the heart-thumping pace of the book demanded more sober tones.

As much as I would have loved to use this brilliant cover design by Jason Gurley, the heart-thumping pace of the book demanded more sober tones.

Here are some comments from the initial reviews on Amazon.

Things get interesting from the very beginning as crew members are attacked by, you guessed it, Little Green Men.

.

The story is wonderfully suspenseful, interspersed with some really good humor and with an ending that will leave you with your mouth hanging open! I could not stop turning the pages.

.

This is a terrific adventure story, full of bumps in the night and glowing eyes in the shadows… you won’t be able to put it down

.

The thing I love about Peter Cawdron’s writing is that it is atypical. It’s something I would have never thought of or have ever read else where. I enjoyed every page of this story

.

You can find Little Green Men for 99c on Amazon.

If you do read this story, be sure to leave a review as I’d love to hear your thoughts on it.

August 24, 2013

Robotics & Humanity

Here’s an interesting article about the history of robotics, reblogged from The Conversation via scitable

~~~

The truth is no stranger than fiction when it comes to robots

Robots represent the cutting edge in science. For decades we have been promised a bright future in which these human-like machines will become so advanced that we won’t be able to tell the difference between them and us. But are technologists really dabbling in the unknown in their work or merely ripping a page out of their favourite sci-fi novel?

Robots existed in fiction long before science made them a reality. In the 1920s, Czech playwright Karel Čapek wanted to create a character that could reflect the dehumanisation of society, the obsession with production and the jubilant celebration of technological progress that often resulted in the horror of the battlefields.

Having already experimented with using different non-human characters like newts and salamanders to reflect on human life and existence, Čapek made “the Robot” a central character in his play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). The Robot was a particular kind of “other” who looked and acted like a human being but lacked something unique – feelings. It was not the product of a mother and father but of a production line. For Čapek, it seems, the robot is an inherently political character, a revolutionary even.

But even this was not the first time that artificial beings had been used by creative writers. The cultural narrative of creation goes back to a time when humans first began to craft objects from material things. Some of these objects were shaped to look like humans. Take the Venus figurines that date back at least 35,000 years, or dolls, which have long been more than just innocent playthings for children in some cultures. Dolls can be magical talismans and, for some, the miniature representation of the human form was a useful way to control the human adult it was supposed to represent. The particular ways in which humans are represented is culturally specific but the desire to represent is, and always has been, universal.

So what is the modern technology of robotics doing that is so different from all these fictional exercises in imitating the human form? The roboticists and technologists of today would have you believe that their work is grounded in scientific reality when they seek the next big breakthrough in artificial intelligence. Cyberneticians and futurologists make claims as if the issues they address were never before considered in human society. But they are in fact more swept up in fantasy than ever before.

All attempts to represent the human form tap into a timeless motivation to know who we are: the mystery of life, reproduction, childhood and attachments to other humans, animals and nature.

What is exciting about AI and technology is that these provide new ways of representing the human form. But the debate about what that means is so confused and ridiculous at times it can leave futurologists lost in their own fantasies. In the 1960s, Marvin Minsky was so optimistic about the new field of AI, he believed that, by the end of the 20th century, machines will outsmart human beings. This is, in part, what inspired Arthur C. Clarke when he speculated about the future of intelligence in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Ray Kurzweil is another case in point. In books such as The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, Kurzweil is forever predicting that we will merge with machines and be able to upload our “complete” consciousness into machines. This idea is emerging as the next big challenge in robotics but it could equally be viewed as a basic feature of human cultural existence.

I’m “uploading” my consciousness right now into this article. A visual artist, when she paints is also “uploading” her consciousness. Consciousness is just another way of saying psychic life – the life and impulses of the individual as a member of a family and collective. Arguably, any human being that has ever created anything has transferred aspects of their consciousness to artificial materials.

The fiction is now being created by the scientists. AI roboticists are given a free reign to project any fantasy they like about their technology and how it will irrevocably change what it means to be human. We have been asking the same question since the beginning of time in different ways. The only difference now is that those building the robots and AI systems believe their work is unique rather than part of an ongoing process and also stand to acquire a lot of money in the process.

~~~

I find it fascinating that the concept of robots arose out of the traumatic experience of battlefield technology in World War I, and in this regard there is a parallel with Lord of the Rings, which also drew on the horrors of that war for its grotesque, senseless violence. Like fire, technology is a wonderful slave, but a lousy master. And for Čapek, seeing technology so grossly abused in The Great War raised the question of “What next?” Could machines one day mimic and replicate humans, eventually replacing them? And that’s been a common theme in science fiction ever since.

August 9, 2013

Life in outer space

Is there life in outer space?

It may surprise you to realize that this is a question for which we already know the answer: Yes.

Earth is a wonderful example of how life can flourish and abound with astonishing diversity in the midst of the extremely harsh, radiation filled vacuum of space. And this highlights a perception flaw we have when considering life in outer space. We see Earth as distinct and separate from space, but it’s not, Earth is drifting through outer space. Earth is a brilliant example of how life can survive in space.

We live on a modestly sized planet orbiting a rather average star that is currently on the outer spiral arm of an unassuming spiral-barrelled galaxy. Space isn’t something out there somewhere away from us, we are in the depths of space.

Ah, so the question becomes… is there any other life in outer space?

The answer here is almost certainly yes as well, as although we haven’t found life, we have no reason to think that life doesn’t exist elsewhere. We have numerous reasons to think life abounds elsewhere in space. That we haven’t detected life is immaterial, and more a reflection on our inability to examine exo-planets in detail than anything else.

It is a poor sailor who never wants to see beyond the horizon – Plato

As for those who belittle SETI (the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), one has to wonder what they would have said in the days of Christopher Columbus, or about the folly of Charles Darwin setting sail on the HMS Beagle? Exploration defines the quintessential character of humanity, as it is the only catalyst for learning. Whether it be exploring concepts in books or cataloging butterflies in a forest, whether it is a scientist looking for life on Mars or a young child looking for bugs beneath a rock, our curiosity defines us.

Horizons are immaterial. Horizons exist only from the perspective of the viewer. Horizons are an artificial boundary that can be probed and explored, and nowhere is that more true than in the search for life in space.

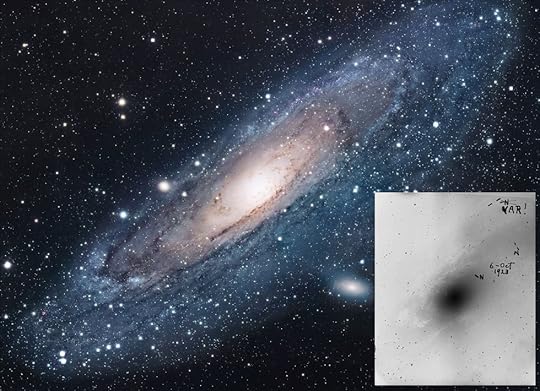

Astronomy is accelerating in its ability to expand our horizons. For hundreds of years, astronomers and philosophers like Immanuel Kant considered the idea of “island universes,” but it wasn’t until the 20th century that the notion of distinct galaxies emerged. Erwin Hubble took this image of Andromeda (inset) from the Mount Wilson Observatory. While the Hubble Space Telescope has given us this iconic image of Andromeda in astonishing detail and allowed us to view tens of thousands of galaxies stretching billions of years back in time.

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey has mapped almost a million galaxies in a small slither of space, implying that the overall number of galaxies in the visible universe must be somewhere in the hundreds of billions. It is a poor soul indeed that would not want to see this magnificent universe examined in greater detail.

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey has mapped almost a million galaxies in a small slither of space, implying that the overall number of galaxies in the visible universe must be somewhere in the hundreds of billions. It is a poor soul indeed that would not want to see this magnificent universe examined in greater detail.

One question that comes up quite often is, “If there is life elsewhere, why haven’t we found evidence for ET?” Seth Shostak in his non-fiction book Confessions of an Alien Hunter, notes that if our galaxy was a haystack then we’re sitting on at least one needle in our solar system. With our efforts so far to examine the stars around us, we have conducted a thorough search of a spoonful of hay and arrived at the conclusion there are no other needles in our sample, but our sample is clearly not representative of the haystack as a whole.

Extending the analogy further, scientists estimate there maybe as many as five hundred billion haystacks to consider, but we can only effectively examine one side of the haystack we’re in. We have no idea how many other needles there may be in our haystack, let alone how many needles there may be in all the other haystacks, but that haystacks have needles is beyond dispute as we’re sitting on one.

Extending the analogy further, scientists estimate there maybe as many as five hundred billion haystacks to consider, but we can only effectively examine one side of the haystack we’re in. We have no idea how many other needles there may be in our haystack, let alone how many needles there may be in all the other haystacks, but that haystacks have needles is beyond dispute as we’re sitting on one.

When it comes to life in outer space, we’ve got to remember that time is a factor as well.

Take a look at this planet. Do you think it could support life?

Because this is what Earth probably looked like during the Hadean eon shortly after the planet formed. Tectonic plates formed a thin crust over the planet. Due to the extreme pressure of the predominantly C02 laden atmosphere, a liquid ocean formed at a scalding 440-500F (beyond 230C). The newly formed Moon orbited at a fraction of the distance it does today, causing massive tidal waves hundreds of feet high to sweep the planet every four hours.

As Earth cooled, it was subject to the Late Heavy Bombardment with tens of thousands of meteor impacts reaching 12 miles in diameter (20km), roughly forty massive impacts left craters in excess of 600 miles in diameter (1000km), and there were a few whoppers that carved out basins 3000 miles in diameter, that’s roughly the distance from New York to Salt Lake City. And yet, somehow, in the midst of Dante’s inferno, life arose.

What would we have made of Earth if we’d spotted her from afar with the Kepler space telescope at this time? Would we have suspected that the simplest of microbes were already arising amidst this seething hell?

How about this world?

Could this world hold life?

Because as best we understand the evidence, Earth went through several “snowball” periods over the past few billion years. Each of them came perilously close to extinguishing life on Earth.

Because as best we understand the evidence, Earth went through several “snowball” periods over the past few billion years. Each of them came perilously close to extinguishing life on Earth.

Our planet is 4.4 billion years old. For at least 3.8 billion years there’s been life on Earth, which is a staggering fact when you stop and consider that the universe itself is only 14+ billion years old. For just under a third of the time the universe has existed, there has been life on Earth! And on Earth, life has endured seemingly insurmountable odds to survive for over 80% of the planet’s history. These are particularly heartening facts when we consider our search for life elsewhere.

We may only have one confirmed example of life in outer space, but it is spectacular in its longevity, its tenacity and its diversity. We have no reason to think the same process hasn’t been replicated elsewhere throughout the universe.