John J. Gaynard's Blog, page 7

November 28, 2012

Review of Declan Burke's SLAUGHTER'S HOUND

In the Irish crime fiction writer Declan Burke's latest novel, Slaughter's Hound, we renew acquaintance with Harry Rigby, the hero of Burke's 2003 noir debut, Eightball Boogie.

The ending of the previous novel is mentioned often in Slaughter's Hound, so I don't think I'll be plot spoiling by saying that Harry killed his crazy brother Gonzo, in self-defense, at the end of Eightball Boogie. Since then, Harry has paid for his crime over a number of years in different prison and mental institutions in Ireland. The path traveled by Harry in Slaughter's Hound is shaped by the events of Eightball Boogie.

But Harry is a different man to the one we met in Eightball Boogie. He has lost his happy-go-lucky attitude to life. No more the opportunistic chancer who lives by his wits, now he is pushed to his wit's end, lured by the fates into situations where every person he comes across tries to exploit his basically honest nature, where he is driven to the limits of insanity, to the point of indulging in crazy acts of violence and torture that only a man who knows he has lost everything will even contemplate. The first violent act in the novel is the suicide of a friend he had met while they were both being held under lock and key. At that moment begins a plot based on smoke and mirrors, intended to deceive Harry in ways that will benefit nearly everybody else in the story except himself.

Right from the beginning, the reader wonders why Harry has gone back to Sligo. Why couldn't he just have headed for anonymous pastures new, in Dublin, London or New York, where in time he could have forgotten his Judeo-Christian responsibilities to woman, son and false friends? But, if Burke had allowed Harry Rigby to escape from his conscience, there would have been none of the verbal pyrotechnics he treats us to in this book, none of the one-liners about the former Irish real estate moguls, now transformed into necrophiliacs screwing the zombie that is NAMA, none of the black humor about Bartholomew Ahern and his ilk, none of the page-turning tragedy as Harry Rigby is manoeuvred into self-destruction.

Back in Sligo Harry lives a hand-to-mouth existence and poisons himself with questions of conscience. In the effort to make a nearly-honest living, he drives a taxi for an ex-INLA man who needs the taxi company as a front for drug-dealing. How far should Harry get into the drug dealing himself? Should he or should he not form a new relationship with the woman he thought had borne him a son, Ben, but who in fact had brought into the world his brother's son and betrayed him in other ways? (Why does Harry never use the word "nephew" in relation to Ben?) Should Harry continue to maintain the fiction of being the boy's biological father? While refusing to see the boy, he tries to assuage his guilt towards him by paying monthly maintenance payments to Ben's mother, who is in less need of the money than he is himself.

This novel is a tragedy, which takes place in a town called Sligo, a location could be Thebes or any other place in the world where the frailties of good men and women are exploited by the eternal cynics and they become the playthings of the Gods, where a man can sleep with his mother without knowing she is his mother or kill his father without knowing whom he is killing, and be punished as if he had knowingly committed the two heinous crimes. As he twists and turns in the nets that have been set for him, the hero's every good intention or action goes wrong, and Harry Rigby reminds you at times of Job and at other times of Oedipus. His every decent human trait, such as loyalty or friendship, is exploited by the people around him and each betrayal plunges him a little further into the circles of hell. It is at the point where Harry, basically a man who wishes to be good, finally accepts that he should renew his relationship with his ex-partner and her son that the Gods really decide to prove that no good thought or deed from him will go unpunished: they conspire to kill the most precious thing in his life. Of course, Harry again gets the blame, but at that point there is no torture left that can be worse than the one he wishes to inflict on himself.

Highly recommended.

Published on November 28, 2012 11:37

November 13, 2012

Review of Gerard Cappa's BLOOD FROM A SHADOW: a scathing indictment of motherhood and apple pie

Blood From A Shadow is an action-packed

political thriller from Belfast writer Gerard Cappa, told in the first person. The hero, Con Maknazpy (who, in

the beginning, thinks he is the son of an Irish-American Pole), is a veteran of the Iraq

war suffering from PTSD whose family life back in New York is going to pieces.

Although he knows he should spend his time reconciling himself with the disillusioned wife and

son, who have borne the brunt of his erratic behavior since he left the service, the simple Irish-American value system which he holds dear, the

devotion to his childhood friends, and his unquestioning belief in his

country, right or wrong, all make him easy fodder to be tricked into a

Kafkaesque situation (think: the Castle) in which, like a piece of useful meat, he is fed blindly through an evil sausage making machine that involves halts for ever more poisonous ingredients in Belfast, Rome, Istanbul and back in New York.

As the novel begins, he thinks the duty he is inveigled into performing, by a person he trusts in New York, is to inform the mother of a childhood friend of the friend’s death, but every few pages the task and the environment change. Until quite close to the end of the novel, as he is led from being the unwitting killer from one violent situation into yet another, he doesn’t know what the hell is going

on.

As an upstanding Irish-American, for whom the ould sod is paradise, there

are a couple of hilarious scenes at the beginning of the book after he stumbles

into a loyalist pub in Belfast and shows the IRA tattoo on his arm. Later in the novel, Con shows himself to be more at home among the Yazidis and gypsies of Istanbul than in the

segregated capital of Northern Ireland.

Throughout the book, a Rambo-like Con continues

to flounder for meaning as he fights to uphold his values by making the corpses around him pile higher. His philosophy is a

simple one. “Shit happens” and when shit happens, you have to act or react.

Every institution, or representative of one, with which he comes in contact, uses and betrays him; the Catholic Church, the CIA and other shadowy American intelligence organizations,

his PTSD counselor, the Israeli and Brit plotters who wish to bring down a

second 9/11 on the United States, hazy groups of drug runners.

Wherever the true red-white-and blue Con can be manipulated

into killing one of their private targets, one of these groups or organizations

will make a tool of him.

The only institution that gives Con any sort

of respite from violence or help is, ironically, the Anglican Church in Istanbul

The end

of the book reveals the awful secret, by American standards, that the root of

all evil lies in the hoary myth of motherhood and apple pie. For their own

ends, Irish-American mothers will favor one child over another, while conditioning them both for Uncle Sam or faction fighting. At the same time as their mother’s milk makes their boy children simple, honest men who respond gratefully to calls to arms, it also blinds them to the truth of how they will be exploited for partisan ends. The

men like Con who volunteer, believe in the nobility of their cause, but ultimately find the

real reason they are sent to places like Afghanistan and Iraq (and previously

Vietnam) is vilely to butcher many more innocent women and children than enemies bearing

arms, and then live with the consequences of their war crimes.

Once these

traumatized men leave the service, they are left on their own to struggle with their physical and psychological handicaps. Anybody who has read this far will understand that I have a beef about the way American veterans have been treated after serving their country. Nearly every institution that promises to help them lets them

down or even, as in Con’s case, willingly throws them back into harm’s way.

On one level, Blood from a Shadow, can be read

as a page-turner, and on that level it works perfectly. I can recommend it highly to anyone who wants thrills from beginning to end and value for their money. The reader will lose count

of the bodies Con leaves in his wake, not only the guilty but also the innocent

men and women in the netherworld of Istanbul whom he blithely recruits to help

him, paying no attention to the price they will have to pay, until it is too late to save them from him.

But Cappa does not present Con solely as a mindless Rambo figure. Although limited by the cultural boundaries of his upbringing, Con is an observer who becomes keenly aware of the individuals, men, women and children he sees in Iraq and Turkey and realizes that the people who have been misrepresented to him as primitive and violent are, in many ways, equal or superior to the ones he comes from, which have been waging terrible warfare and attempted genocide on the rest of the world since the beginning of the modern era.

So, on another level, this book can be read as a scathing indictment of what Northern Irish bigotry, American redneck patriotism, the billions of Western dollars invested in weapons and men of mass destruction, what Eisenhower described as the "military-industrial complex", and the wish to transform the rest of the world into fawning clones of Western democracy can do

to their own trusting children: make monsters of them. In this novel, Con begins to doubt the ideology that formed him: he cannot ignore the finer points of the people and cultures he has been trained to destroy. That is what makes Blood from a Shadow even more than an action thriller. Con kills in the name of all he believes true, until the point where most of what he believes true is revealed to him as false. Stuart Neville’s Ghosts of Belfast comes to mind, in the way

it delineated how the people who did the actual killing during the troubles are

haunted by their ghosts while many of the cute bastards who manoeuvred them into it are now swanning around the Northern Irish Parliament, with all expenses paid.

A few reviewers on Amazon have drawn attention

to the parallels between Cappa’s novel and Irish mythology, so I won’t go further into

those aspects of the novel. Below are a few parallels of my own that came to mind as, I was reading it.

I am a country music fan, so the first parallel was listening to

Toby Keith, in a crowded hall in Tennessee, singing The Red White and Blue and An American Soldier, both of which you can listen to on Youtube (be patient for the first minute, as the ad works its way out of the frame). Keith could be singing about Con or his friend, Ferdia.

A second parallel, is one of the verses from Tom Paxton's song, "When Princes Meet", which describes how, once a poor little man like Con has already served, he "must do more". There are many powerful descriptions in the novel of how all the great lords he thought he could trust betrayed him:

"When kings make war, the poor little men must fight them./They must do more,

They hold out their necks for great lord's swords to bite them./The sons of the lords cleave through their ranks,

In the hopes some warrior king might knight them./It's what the poor little men are for, when kings make war."

A third parallel came to me during the novel's descriptions of the atrocities committed by Ferdia and/or Con in Iraq, a quote from the Duke of Wellington. The Wellington I'm thinking of is the one who is said to have said before the Battle of Waterloo, "I don't know what effect these men will have upon the enemy, but, by God, they frighten me."

Cappa's novel shows that, although we in the West are proud of our recent technological progress and "civilizing influence", in truth we are still the same Norman warlords, Teutonic knights and Frankish crusaders who colonized the non-Christian parts of Europe in the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries by putting to the sword any peoples, especially the Scandinavians, who did not blindly accept our diktat of the one true faith. We're continuing to frighten the hell out of nearly every civilization we've come in contact with over the past five hundred years. The one thing that may save us is the realization by the Con Maknazpy's of this world that they can shuck off the indoctrination that began in the cradle and open up to the gentler influences of other traditions, cultures, philosophies and belief systems.

You can buy Blood from a Shadow from Amazon

Published on November 13, 2012 11:06

Inheriting Abraham: Enlisting the Biblical Abraham as Peace Broker

In my first novel, Another Life, quite a bit of the suspicion for the murder revolved around an Abrahamic sect that had come into existence in the market town of Ballina in County Mayo, in the West of Ireland. The founders of the sect were looking for meaning, some mode of existence that would allow them to escape from their sordid and violent pasts as petty criminals and jailbirds and live a decent life. Although most of them were of a religious bent, they were all in agreement with one fact: they didn't want to hitch their broken down wagons to any form of modern religion, which had wandered far afield from its founder's vision, behaviour, actions and words. Thus the will not only to go back to Abraham, the patriarch of all three of the biggest monolatrous religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam, but to go back to Abraham's mother and thus avoid the controversies introduced around his two sons, Ishmael and Isaac.

Given the research I put into writing that novel, I was particularly interested to see an article by Jon D. Levenson, about his latest book, in yesterday's edition of the Wall Street Journal. The title of the article was Enlisting the Biblical Abraham as Peace Broker and the title of Levenson's book is Inheriting Abraham: The Legacy of the Patriarch in in Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Below are the first few paragraphs from Levenson's Wall Street Journal Article, which sum up exactly why the members of my sect in Ballina wished to go back to the source of monotheism:

Confronted with seemingly endless discord in the Middle East—much of it said to be rooted in religious difference—scholars and laymen alike have been promoting the idea of "Abrahamic religion." This is the notion that Judaism, Christianity and Islam are equally indebted to the figure of Abraham, the patriarch prominent in the scriptures of all three. Surely, the theory goes, the three communities can move toward much-needed reconciliation by considering their shared origins.

This is a message that the more fanatical members of each community need to hear, but their very fanaticism makes them unlikely to listen. One might also question whether theology, rather than culture and politics, is what lies at the heart of anti-Western and anti-Israeli rhetoric in the Middle East. Commonalities and cross-influences do exist among the three religions, but no less worthy of attention are the differences.

The idea of Abrahamic religion is usually tied up with the notion of Abraham as the first monotheist. To the best-selling author Bruce Feiler, Abraham was "the first person to understand that there is only one God," and this insight is "the shared endowment of the Abrahamic faiths."

But the familiar image of Abraham as the discoverer of the true God and the uncompromising opponent of idolatry isn't found in Genesis or anywhere else in the Hebrew Bible. It is an idea that originated in Judaism after most of the Hebrew Bible had been composed, and from there it spread into the literature of the Talmudic rabbis and later into the Quran, forming an important commonality between Judaism and Islam.

You can read the rest of the article here: Enlisting the Biblical Abraham as Peace Broker. I also encourage you to read the 95 comments (at last time of counting) the article has provoked. I hope the article and comments will encourage you to buy Jon D. Levenson's book and see how its scholarship coincides or differs from the erratic, and finally doomed, seeking for peace of the members of my sect in Ballina.

My novels, The Imitation of Patsy Burke, Another Life and Green Blood is for France, can be purchased from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr and Amazon.de in either print or electronic versions.

You can find them by following any of the links below:

Amazon.com (Amazon in the United States)

Amazon.co.uk (Amazon in the U.K. and Ireland)

Amazon.fr (Amazon in France)

Amazon.de (Amazon in Germany)

Published on November 13, 2012 03:02

November 5, 2012

Thank you, Friends: 289 complimentary Kindle copies of 'Green Blood is for France' downloaded yesterday

I just checked the stats on Kindle Direct Publishing and saw that the free promotion of my new political crime novel, Green Blood is for France, resulted in 289 downloads yesterday.

Thank you all!

I promise there will be no more three-hour blitzing of the free offer on Twitter, which I ran as an experiment!

The experiment showed that there are diminishing returns. The first couple of times you tweet the free offer you get a good number of ReTweets and Favoriting, but the last two or three times (of eight tweets in all) the increase in retweets or downloads was marginal .

I also promoted the free promotion in a couple of places on Facebook.

For anybody interested in statistics, here is how the downloads spread out geographically:

United States: 220

United Kingdom (probably including Ireland): 56

Germany: 6

France: 5

Spain: 2

Below is the back cover blurb for Green Blood is for France:

The near-naked, mutilated body of a young black woman is washed up on a remote beach in the west of Ireland. The search to find her killer takes Timothy O’Mahony far from his placid existence as a Garda sergeant in Bangor Erris into the corruption and machinations surrounding the election campaigns for the next President of France. With his prime suspects in the inner circle of Laurent Delahaye, the main opposition contender for the Presidency and womanising one-time leader of the Social Democratic party, O’Mahony finds that even senior French judges and policemen cannot always be relied upon to be impartial when a case may have political implications.

His own position becomes increasingly difficult as he follows the trail to the Congo and finds a link between its brutal dictator, a French oil company, at least one of the suspects, and the dead woman. When he loses the cooperation of his French colleagues and is taken off the case, O’Mahony, in his search for justice for the murdered girl and her family, finally has to call on the help of the Irish travelling community, known for their distrust and dislike of the Irish police.

Download the Kindle version of Green Blood is for France from Amazon.com

Download the Kindle version of Green Blood is for France from Amazon.co.uk

Published on November 05, 2012 04:02

November 4, 2012

My French political crime novel, Green Blood is for France, free today on Kindle

The Kindle version of my latest novel, Green Blood is for France, a tale of murder, French intelligence service skullduggery in the run up to the French presidential elections, libertinage and patient investigation by The Republic of Ireland's finest trilingual detective, Timothy O'Mahony, is available for free today on Kindle.

Here's the burb:

The near-naked, mutilated body of a young black woman is washed up on a remote beach in the west of Ireland. The search to find her killer takes Timothy O’Mahony far from his placid existence as a Garda sergeant in Bangor Erris into the corruption and machinations surrounding the election campaigns for the next President of France. With his prime suspects in the inner circle of Laurent Delahaye, the main opposition contender for the Presidency and womanising one-time leader of the Social Democratic party, O’Mahony finds that even senior French judges and policemen cannot always be relied upon to be impartial when a case may have political implications.

His own position becomes increasingly difficult as he follows the trail to the Congo and finds a link between its brutal dictator, a French oil company, at least one of the suspects, and the dead woman. When he loses the cooperation of his French colleagues and is taken off the case, O’Mahony, in his search for justice for the murdered girl and her family, finally has to call on the help of the Irish travelling community, known for their distrust and dislike of the Irish police.

Download the Kindle version of Green Blood is for France from Amazon.com

Download the Kindle version of Green Blood is for France from Amazon.co.uk

Here's the first chapter:

‘So, instead of hanging in there to discover

who really killed her, your new investigating judge prefers to make a murder

case against a dead man?’

Timothy

O’Mahony kept his voice under control, but the flash of anger in his eyes was

clear to the man across the table. They sat near the window in a stuffy,

unpretentious restaurant in Levallois-Perret,

the Paris

suburb that since 2008 had been home to the DCRI. O’Mahony hadn’t appreciated

being squeezed into a wooden chair three times too small for him. Now, he

didn’t appreciate being toyed with.

The

Commissaire who was O’Mahony’s contact in France’s Central Directorate for Internal

Intelligence, the DCRI, looked perplexed as he confronted the slow burn in the

hazel eyes of the massive Irish policeman. How naive could this man, O’Mahony,

be? During his lifetime, how many violent, politically inspired deaths had he

come across, and what had he learnt from them?

Nothing,

it would seem.

But

the DCRI agent hesitated. Did the Irish policeman wish him to continue to

search for an imaginary assassin? Or was it he, the agent, who was being

considered naive by the Irish policeman? Did O’Mahony sincerely believe that

the man the Public Prosecutor had accused of the murder was innocent?

Although

the two high-security buildings at the DCRI Headquarters were nine and eleven

floors high, the complex was referred to by other French intelligence agents,

national policemen and gendarmes as “the bunker in Levallois”. It housed more

than sixteen hundred administrative staff and intelligence operatives. The

Corsican at the head of the DCRI, known to his friends and enemies as the

Shark, was fond of boasting that since the creation of the Central Directorate

from two separate intelligence agencies, he was now the head of the French FBI.

The

Shark and all the agents in charge of special operations had offices on the top

floor of the bunker’s front building. Right next to the complex was a

one-storey biological foods store, which housed a small café. The café had been

put off limits to all DCRI agents. It had got around that they talked too

openly in there about State secrets.

Now,

for early morning coffee, lunch or evening drinks that went on until midnight,

DCRI agents met with Islamist terrorist touts, journalists or people from the

other French intelligence agencies in small neighbourhood restaurants within

five hundred yards of the bunker. In a few of the restaurants, they’d managed

to get waitress jobs for their wives or mistresses, one man’s mistress

sometimes being another agent’s wife. The majority of DCRI employees were men.

They earned a fairly decent wage as career civil servants, but not high enough

to ensure that their women didn’t need to work.

O’Mahony

asked the agent, ‘What will happen to your career if President Esterhazy loses

his bid to get re-elected?’

‘The

DCRI is a giant bureaucracy, Timothy. Every piece of white paper with print on

it has to be signed off by at least four people as it moves up the hierarchy.

Every person sitting on his arse in the senior echelons is looking for

something they can turn into what they call a “blue paper”, a juicy piece of

information that can be sent to President Esterhazy’s palace to nourish his

paranoia. An average DCRI agent is not judged by his intelligence or

competence, but solely by how blindly he obeys orders and how much information

he can find that President Esterhazy will take seriously for a couple of

minutes. Agents who question an order will find themselves, a couple of days

later, undergoing a medical examination that always concludes they’re

suicidally depressed or psychotically disturbed.’

‘Are

you an average DCRI agent?’

‘No,

I believe there are better ways to protect France than by blindly obeying

orders.’

The

DCRI agent would react with righteous anger if O’Mahony accused him of being

complicit in a political assassination. But couldn’t he see, that by putting

his own political values above his duty to be impartial, he was betraying his

duty to see the law of the land respected?

‘Apart

from that,’ said the agent, ‘politics is a subject that holds no interest for

me. France

has had hundreds of regime changes over the past fifteen hundred years. She has

often plumbed the depths, and she has always managed to recover when a strong

man has been at the controls.’

‘Won’t

the men around the new president think you played politics, when you went along

with the people who accused a dead colleague of his of committing murder?’

‘The

man you have in mind will not be the new president and, even if he is, Monsieur

O’Mahony, you should realise that I’m astute enough to have covered my backside

with politicians on both sides. Left wing or right wing, both sides need men

like me more than we need them. They use me for their short-term objectives,

and I use them for my long-term ones.’

NOW:

Download the Kindle version of Green Blood is for France from Amazon.com

Download the Kindle version of Green Blood is for France from Amazon.co.uk

And, afterwards, if you can spare a few minutes please leave a short review on Amazon.

Published on November 04, 2012 02:23

November 2, 2012

My new resolution: don't engineer the killing of helpless hospital patients

This blog has now been silent for more than a month. The reason is that I was poleaxed by what I will call, euphemistically, one of life's accidents. The month I spent in hospital allowed me to appreciate how professional, competent and kindly the French hospital system is. Lying awake at night, pinned to a hospital bed and being dependent on the kindness of strangers, gives you a lot of time to reflect on what you should have done differently in life, and how you are going to change if ever you get out of the situation you find yourself in. One of the things I began to regret was that, in my first novel, the murder victim was a person lying helpless in a hospital bed, a person who found himself in more or less the same situation I was now in.

A lot of stuff has been written about about the author's responsibility to his or her victims. My new resolution is never again to have one of my murderers kill a vulnerable patient. The victim should at least have a fighting chance to protect him or herself. To show you what nourished this reflection, below you will find the first chapter of my novel Another Life.

HIS FINGERS were clenched

high around the smooth handle of the kitchen knife that had been driven into

his heart, the heel of his hand towards him. It had gone in too easily. It was

his knife but he hadn’t had the strength to parry its use against him. He

should never have shown it.

Death would soon be upon him. The long-robed hellish

figure backed slowly away from him, abandoning him in this hospital bed. Behind

him the lights of the transfusion equipment flashed. Should he try to pull out

the knife or leave it where it was? He left it in. A warm tear filled his right

eye. It moved to the edge, hung there for an instant and then rolled down his cheek

to his neck. He shuddered.

His thoughts jumped haphazardly through the film of

his life: the images of the pleasant, the horrific, the shameful; the cuddles

and the warmth of his mother’s love; the carefree childhood in Manchester; the

drugs and the riots; the women and children he had wanted to love but whom he

had nearly always abused and abandoned; the Sodomite Canal; the uncontrollable

drinking of his first years back in the West of Ireland; the killing; the

Sodomite Prison; the inability of his own brother to understand him; his

salvation through the finding of the One True God. and His Prophet.

Who could have guessed it would end in this way, at

this moment, in the time when he was beginning to succeed at living

righteously? It was not up to him to question Why? Nobody knows the day, nobody

knows the hour, what is important is to be prepared at all times. Thank God: he

was better prepared now than he had ever been.

This world was the one and only chance to earn the

gift of Paradise. Had he been able to do

enough in the last few months to earn entry to eternity in a place of delight

or would he still have to face a passage through the fires of Hell? In any

case, it was now too late to do more. Except to say the prayer, his own prayer,

“God is Great and

Abraham, the son of Amatlai, is his prophet!”

After a sharp intake of breath, he breathed out for

the last time.

My novels, The Imitation of Patsy Burke and Another Life, can be purchased from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr and Amazon.de in either print or electronic versions.

Read the Kirkus Review of The Imitation of Patsy Burke

Find my novels by following any of the links below:

Amazon.com (Amazon in the United States)

Amazon.co.uk (Amazon in the U.K. and Ireland)

Amazon.fr (Amazon in France)

Amazon.de (Amazon in Germany)

Print and electronic versions can also be purchased from Barnes & Noble in the United States. Find them by following the link below:

barnesandnoble.com

Published on November 02, 2012 04:10

September 24, 2012

A Recent Film and a Magazine about the French Foreign Legion

French Foreign legionnaires have a walk on part in the novel I'm finishing at the moment, Green Blood is for France, and will probably figure in the next one.

Le Spectacle du Monde, a French monthly magazine, has this to say about its September edition, which gives the Legion pride of place.

"An elite corps like no other, the French Foreign Legion continues to embody against all odds, the rejected or forgotten virtues of a society without defining values and without discipline. This is why it remains so popular.

Founded in 1831, the Legion prepares to celebrate, next spring, the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Camarón, which took place in Mexico in 1863. The tradition of this celebration dates back to 1906. A mythical battle, Camarón by itself sums up the history and spirit of the legion: the expedition to a foreign land; the heroism and sacrifice pushed to their supreme limits by foreign volunteers in the service of France.

Coming from all five continents, these volunteers give their all to the Legion, sacrificing their past and offering their lives. In return, the Legion offers them a salary of glory and of pain, of grandeur and of abnegation. It becomes their family, their homeland. 'Legio Patria Nostra' ('The Legion, our homeland') is the motto of the Legion, complemented by two other phrases: 'More Majorum--After the manner of our ancestors' and the one that crowns the other two: 'Honneur et fidélité--Honor and Loyalty'."

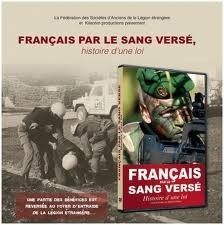

Many people think that French foreign legionnaires have long had the automatic right to become French, but this is not the case. Even when a legionnaire was injured in combat it didn't give him any special privileges until 1999, when a law was voted in that gave automatic French citizenship to any legionnaire who had shed his blood for France. A 52 minute film has recently been produced, titled 'Français par le sang versé--French through spilled blood', which tells the story behind the fight to get the law adopted. People interviewed in the film include Mariusz Nowakowsky, injured in Sarajevo in 1993; Joao Ribeiro de Almeida, injured in Côte d'Ivoire in 2003; and Jia wei Zhang, injured in Afghanistan in 2010.

If you wish to learn more about the Legion's recent history you can read Major Charles H. Koeller's Legio Patria Nostra: The History of the French Foreign Legion Since 1962

Published on September 24, 2012 09:04

September 17, 2012

Molière's Miser Translated into Wesh-Wesh & Your First 20 Words of Wesh-Wesh translated into French and English

An article in last Saturday's Le Parisien newspaper announced that a young Frenchman, Jean Eyoum, has adapted Molière's play The Miser (L'Avare) into Wesh-Wesh, "the language of the cities". The title of Eyoum's adaption is Super Cagnotte, which could be translated as "Mammoth Lotto Jackpot". Eyoum hopes that now he has been able to publish the updated play he will soon find a producer.

When French people refer to "the cities", they don't have in mind Lyon, Marseille or Paris, but the low-cost public housing projects that ring them. Up to 100 different nationalities can live in these "cities" and the language that is spoken there, while rooted in everyday French, is influenced by the vocabulary and syntax of Arabic, as it is spoken in North Africa, and any number of sub-Saharan African languages.

Wesh-Wesh can also be written ouèche-ouèche. The word Wesh is said to come from the Arabic "waach", which can be translated variously as "Hi!" and/or "What's up?". However the word "Wesh" is not always at the beginning of a sentence. It can be placed wherever there is a need for emphasis, such as in the sentence, "Vas-y wesh barre-toi !" which, apart from the word "wesh" in the middle, is standard city French for "Fuck off!" Wesh-Wesh is both the name of the language and the individual noun for the person, usually dressed in a track suit, who speaks it.

The trilingual glossary below presents twenty original Wesh-Wesh words or phrases, followed by the classical French and English equivalents. It does not contain common Wesh-Wesh words such as "Daron" (père, father), "Daronne" (mère, mother) or "Kiffer" (aimer, to love/like) which have now moved into mainstream French argot. This blog post, like any other work, is not original. It stands on the shoulders of the giants who present the Wesh Wesh dictionary on the web site WeshWeshMaster. My contribution to the study of Wesh-Wesh is just to translate some of the more usual words into English so that you will be able to understand Jean Eyoum's play when it is, as I hope, staged.

1) "Wesh" [pronunciation: ouwaiche] = this is the way to start a conversation or to approve of an idea, whether or not the idea is useful. In some cases, it can be translated into French as "Bonjour" and into English as "Hi!"

2) "b1 ou b1" [bien ou bien] or "b1 ou koi" [Good or what] = is the way to ask a person her physical or psychological state and, in this way, proves that the Wesh Wesh has a very positive outlook on life because the expression prevents all negative forms of reply. The French translation is "Comment ca va ?" and the standard English translation is "How are you?"

3) "tkt" [tinkiete] or "tassur" [tassuR] = are two words for showing you value something. Both words show respect for the work done or the idea uttered. The words can be translated into French as "Beau travail" or "Je suis d'accord avec toi" and into English as "Well done" or "I agree with you".

4) "ta vu" [tavu] = this expression allows the Wesh-Wesh to solicit a compliment or a gesture which will flatter his/her ego in front of the group. The Wesh-Wesh being a person who loves compliments, uses this word at the end of nearly every sentence. Can be translated into French as "T'as vu?" and into English as "How good is this?"

5) "ca pete" [ca paite] or "ca dechire" [ca dechiR] or "tro dla bal" [troo dlaaa bAll] (or "tro dla boulette" depending on which region the Wesh-Wesh comes from) = shows the Wesh-Wesh's approval of the situation in which s/he finds (him/her)self. In French this can be translated into "genial" or "beau travail" or "tu as eu une bonne idee" or "c'est joli"... and into English as "Wow!", "Great!", "What a good idea!" or "How nice"...

6) "trankil" [trankile] = is the word that defines the Wesh-Wesh's state of mind when s/he's talking, but it can also be a compliment. Whatever the situation, the Wesh-Wesh is always in a positive frame of mind. Can be translated into French as "Cool" and into English as "Cool".

7) "grave" [graaave] = is a superlative. Can be translated into French as "très" and into English as "very". "Grave belle," for example translates as "Very beautiful"..

8) "Kwa" [kooa] = is a way of reinforcing the main idea in a sentence. But most of the time it is totally useless, apart from showing the Wesh-Wesh's level of linguistic mastery. Can be translated into classic French as "n'est-ce pas?" and into Irish English as "Do you get me?"

9) "Keuce" [queusse] = translates to the classical French word “sac" or the English word "bag".

10) "Blaze" [blase] = when using this word, the Wesh-Wesh is referring to the name or the pseudo of the person s/he's talking about. Translates into French as "nom" and into English as "name".

11) "gros" [gros] = is a way of addressing a man. Translates into French not as "fat man" but as "Monsieur", into Ivy League English as "Sir". You should now be able to translate the sentence, "Wesh gros bien ou quoi?" into French or English.

12) "da" [da] = is the definite article. Translates into French as "le" or "la" and into English as "the". But the jury is still out on whether it's better to use "da" instead of "le" or "la". Above a certain level of linguistic mastery, the Wesh-Wesh sacrifices the capacity to communicate with the rest of civilization.

13) "cacededi" [Kassedeidi] = is a way of dedicating something to someone (for example, a song). This is a derivation from "Verlan", the primary speech form of the Wesh-Wesh. Wikipedia's take on Verlan is that it is "an argot in the French language, featuring inversion of syllables in a word, and is common in slang and youth language".

14) « Represente »[wepuizante] = shows the Wesh-Wesh's pride in representing his community. The word "represente" is followed by the two digits of the Wesh-Wesh's French departement, for example, a person from Saint-Denis would say "Represente 93" and a person from Asnières would say, "Represente 92". The number of the department is not pronounced as ninety-three or ninety-two, but as "nine three" or "nine two".

15) "Poto" [poto] = the friend of the Wesh-Wesh. Translates into French as "copain" and into Australian English as "mate".

16) "keuf" [keufe] = in 1968, this word would have been translated into French as "Flic" or into English as "Pig". More polite translations would be "policier" or "cop".

17) "crew" [krou] = a group of Wesh-Weshes. No need to translate this one into English. In French would probably translate as "bande".

18) "zik" [zike] = the sort of sound listened to by the Wesh-Wesh. French translation: musique. English translation: music.

19) "meuf" [meufe] = translates into French as "femme" and into English as "woman".

20) "caisse" [kaisse] = this is an old French word for "voiture". Translates into English as "car".

If you would like to check out a few more complex Wesh-Wesh words and phrases, I suggest you consult the little dictionary of Wesh-Wesh on the FuckFrance website.

Published on September 17, 2012 08:13

Molière's Miser Translated into Wesh-Wesh & 20 words of Wesh-Wesh translated into French and English

An article in last Saturday's Le Parisien newspaper announced that a young Frenchman, Jean Eyoum, has adapted Molière's play The Miser (L'Avare) into Wesh-Wesh, "the language of the cities". The title of Eyoum's adaption is Super Cagnotte, which could be translated as "Mammoth Lotto Jackpot". Eyoum hopes that now he has been able to publish the updated play he will soon find a producer.

When French people refer to "the cities", they don't have in mind Lyon, Marseille or Paris, but the low-cost public housing projects that ring them. Up to 100 different nationalities can live in these "cities" and the language that is spoken there, while rooted in everyday French, is influenced by the vocabulary and syntax of Arabic, as it is spoken in North Africa, and any number of sub-Saharan African languages.

Wesh-Wesh can also be written ouèche-ouèche. The word Wesh is said to come from the Arabic "waach", which can be translated variously as "Hi!" and/or "What's up?". However the word "Wesh" is not always at the beginning of a sentence. It can be placed wherever there is a need for emphasis, such as in the sentence, "Vas-y wesh barre-toi !" which, apart from the word "wesh" in the middle, is standard city French for "Fuck off!" Wesh-Wesh is both the name of the language and the individual noun for the person, usually dressed in a track suit, who speaks it.

The trilingual glossary below presents twenty original Wesh-Wesh words or phrases, followed by the classical French and English equivalents. It does not contain common Wesh-Wesh words such as "Daron" (père, father), "Daronne" (mère, mother) or "Kiffer" (aimer, to love/like) which have now moved into mainstream French argot. This blog post, like any other work, is not original. It stands on the shoulders of the giants who present the Wesh Wesh dictionary on the web site WeshWeshMaster. My contribution to the study of Wesh-Wesh is just to translate some of the more usual words into English so that you will be able to understand Jean Eyoum's play when it is, as I hope, staged.

1) "Wesh" [pronunciation: ouwaiche] = this is the way to start a conversation or to approve of an idea, whether or not the idea is useful. In some cases, it can be translated into French as "Bonjour" and into English as "Hi!"

2) "b1 ou b1" [bien ou bien] or "b1 ou koi" [Good or what] = is the way to ask a person her physical or psychological state and, in this way, proves that the Wesh Wesh has a very positive outlook on life because the expression prevents all negative forms of reply. The French translation is "Comment ca va ?" and the standard English translation is "How are you?"

3) "tkt" [tinkiete] or "tassur" [tassuR] = are two words for showing you value something. Both words show respect for the work done or the idea uttered. The words can be translated into French as "Beau travail" or "Je suis d'accord avec toi" and into English as "Well done" or "I agree with you".

4) "ta vu" [tavu] = this expression allows the Wesh-Wesh to solicit a compliment or a gesture which will flatter his/her ego in front of the group. The Wesh-Wesh being a person who loves compliments, uses this word at the end of nearly every sentence. Can be translated into French as "T'as vu?" and into English as "How good is this?"

5) "ca pete" [ca paite] or "ca dechire" [ca dechiR] or "tro dla bal" [troo dlaaa bAll] (or "tro dla boulette" depending on which region the Wesh-Wesh comes from) = shows the Wesh-Wesh's approval of the situation in which s/he finds (him/her)self. In French this can be translated into "genial" or "beau travail" or "tu as eu une bonne idee" or "c'est joli"... and into English as "Wow!", "Great!", "What a good idea!" or "How nice"...

6) "trankil" [trankile] = is the word that defines the Wesh-Wesh's state of mind when s/he's talking, but it can also be a compliment. Whatever the situation, the Wesh-Wesh is always in a positive frame of mind. Can be translated into French as "Cool" and into English as "Cool".

7) "grave" [graaave] = is a superlative. Can be translated into French as "très" and into English as "very". "Grave belle," for example translates as "Very beautiful"..

8) "Kwa" [kooa] = is a way of reinforcing the main idea in a sentence. But most of the time it is totally useless, apart from showing the Wesh-Wesh's level of linguistic mastery. Can be translated into classic French as "n'est-ce pas?" and into Irish English as "Do you get me?"

9) "Keuce" [queusse] = translates to the classical French word “sac" or the English word "bag".

10) "Blaze" [blase] = when using this word, the Wesh-Wesh is referring to the name or the pseudo of the person s/he's talking about. Translates into French as "nom" and into English as "name".

11) "gros" [gros] = is a way of addressing a man. Translates into French not as "fat man" but as "Monsieur", into Ivy League English as "Sir". You should now be able to translate the sentence, "Wesh gros bien ou quoi?" into French or English.

12) "da" [da] = is the definite article. Translates into French as "le" or "la" and into English as "the". But the jury is still out on whether it's better to use "da" instead of "le" or "la". Above a certain level of linguistic mastery, the Wesh-Wesh sacrifices the capacity to communicate with the rest of civilization.

13) "cacededi" [Kassedeidi] = is a way of dedicating something to someone (for example, a song). This is a derivation from "Verlan", the primary speech form of the Wesh-Wesh. Wikipedia's take on Verlan is that it is "an argot in the French language, featuring inversion of syllables in a word, and is common in slang and youth language".

14) « Represente »[wepuizante] = shows the Wesh-Wesh's pride in representing his community. The word "represente" is followed by the two digits of the Wesh-Wesh's French departement, for example, a person from Saint-Denis would say "Represente 93" and a person from Asnières would say, "Represente 92". The number of the department is not pronounced as ninety-three or ninety-two, but as "nine three" or "nine two".

15) "Poto" [poto] = the friend of the Wesh-Wesh. Translates into French as "copain" and into Australian English as "mate".

16) "keuf" [keufe] = in 1968, this word would have been translated into French as "Flic" or into English as "Pig". More polite translations would be "policier" or "cop".

17) "crew" [krou] = a group of Wesh-Weshes. No need to translate this one into English. In French would probably translate as "bande".

18) "zik" [zike] = the sort of sound listened to by the Wesh-Wesh. French translation: musique. English translation: music.

19) "meuf" [meufe] = translates into French as "femme" and into English as "woman".

20) "caisse" [kaisse] = this is an old French word for "voiture". Translates into English as "car".

If you would like to check out a few more complex Wesh-Wesh words and phrases, I suggest you consult the little dictionary of Wesh-Wesh on the FuckFrance website.

Published on September 17, 2012 08:13

September 11, 2012

Annie Ernaux on Richard Millet's "A Literary Elegy for Anders Breivik"

In the Le Monde daily newspaper that carries today's date there is an article, written by Annie Ernaux, and signed by 200 prominent French writers, about Richard Millet's eulogy for Anders Breivik, the Norwegian mass murderer. Millet's position in his pamphlet is not only an "elegy" to the mass murderer, but also a set of arguments that multiculturalism is killing French literature.

American and European attitudes to hate speech and censorship are different and I am firmly in the American camp, which says that the answer to hate speech is "more speech", not censorship. This example of "more speech" from Annie Ernaux is to be complimented.

Below are large excerpts from Annie Ernaux's article, in my rough and ready translation.

I read Richard Millet’s latest pamphlet,

Ghost Language followed by A Literary Elegy for Anders Breivik while

experiencing growing anger, disgust and terror. This writer, who is an editor at the Gallimard publishing house, presents

arguments that exude contempt for humanity and excuse violence under the

pretext that he's examining them from the sole angle of their literary beauty; the "acts" of a person who killed 77 people in cold blood people in Norway in

2011. The sort of arguments which, thus far, I had only read from the pens of 1930s writers.(*)

The danger of reacting to this piece of

writing is that the posture of the martyr Millett has created for himself, as a

writer dogged by misfortune and lack of recognition, will be strengthened. But

I will not be silent about it. I also won’t accept that it’s the result of a sort of “delirium”, or “blowing a fuse”, that isn't worth mentioning. That’s

too easy a get-out-of-prison card for a writer well known for his marvelous

command of the language.

Richard Millet is anything but a madman.

Every sentence, every word is written in full knowledge of the facts and, I

would add, of the possible consequences. To respond with silence and contempt to this text, which is a danger for for social cohesion, is to run the risk of

despising yourself later. Because we were silent.

I will not let myself be intimidated,

either, by those who endlessly plead, in a Pavlovian reflex, for freedom of

expression and the right of writers to say absolutely anything. In that case

why not a "Literary Elegy for Marc Dutroux"!(**) Or those who scream “censorship” to silence a person who, after examining what is actually written in this book, dares--what audacity!, to ask questions of a

publishing house as to the responsibilities of its author.

First of all, let’s deal

with the supposed irony of the title, which, according to the author, the dimwit

readers have not understood. This is because the irony is not there. We can

look in vain for even one ounce of it in the book itself. We suspect that

the adjective "literary" is only there for legal reasons, like the precautionary remarks, repeated a couple of times, in which Richard Millet says he does not approve of the acts committed

by Anders Breivik. And to protect himself even further, he is not afraid to use

a fallacy so blinding that it has dazzled his supporters. 1. Literature always

deals with perfection and Evil; 2. Through his crimes Anders Breivik has

brought Evil to perfection 3. Therefore, I will focus on "the literary

dimension" of his crime. Unassailable. All hail the artist who prides

himself on isolating and distilling from a mass murderer his sole "literary

dimension”...

Real literature is dead. What killed it was,

"the populating (repopulation) of Europe by the peoples

whose culture is most foreign to ours," i.e. non-European immigration.

And, with some caution, because the (logical) leap imposed on the reader’s

capacity for reason is huge, the author thumps home his message, "The

relationship between literature and immigration may seem unfounded, but it is

actually central and leads to misgivings about identity". With another

brutal thump, he says that the high stake we are playing for in literature is “identity”.

Therefore immigrants, who are supposed to threaten

"the purity of the French language"--a pipe dream which has never existed; the

person whose memory is rooted in another culture, who has a different heritage than

ours, who lives in the same space as us in the same world, which Millet does not wish

to know about, or accept; therefore, this non-French person of a different "strain",

of a different "blood" is seeping into my imagination, my writing , imposing

on me, without my knowing anything about it, his patterns of thinking? Colonizing

me? I am not exaggerating, I am only trying to apply to myself what Richard

Millet states, that writers are "in a totally new neo-colonial situation. A statement so serious, so incredible that

every writer should feel questioned by it...

Yes, this text which has been rightly been qualified

as disgusting by Jean-Marie Le Clézio is a political act which aims to destroy

the values at the root of French democracy. That is why instead of the cowardly questions

put to him by the media, we must dare to ask Richard

Millet: "What do you want? Border closures? The expulsion of all those who are not French

by 'right of blood?’ What regime do you wish to have instead of this democracy

that you hate so much?"

I've been writing for

more than forty years. Today, no more than yesterday, have I ever felt threatened

in my daily life, in the suburbs of Paris, by the existence of people who do

not have the same color of skin as me, nor have I felt threatened in the use of

my language by those who are not "French by right of blood", speak

with an accent, or read the Koran, but who go to schools where, like I once

did, they learn to read and write French. And, above all, I will never accept

that my work as a writer is bound to a racial or national identity which

defines me by my differences to other people, and I will fight against those people

who try to impose on others this division of humanity....

Bravo, Annie!!! For the whole article, but especially for that last paragraph!

Read the rest of this article on Le Monde website: "Le pamphlet fasciste de Richard Millet déshonore la littérature"

You can also read a very comprehensive article on the subject by Bruce Crumlee, writing in TimeWorld: French Essayist Blames Multiculturalism for Breivik’s Killing Spree

Below are the first two paragraphs from Bruce Crumlee's excellent article:

Richard Millet is an accomplished figure in French literature. His book Le Sentiment du Langue (The Feeling of Language) won the Académie Française’s 1994 essay award. His work as an editor for celebrated publisher Gallimard, meanwhile, helped produce two recent Prix Goncourt winners — including the 2006 novel Les Bienveillantes(The Kindly Ones) by American author Jonathan Littell. Now, however, Millet is getting attention of an entirely different kind with a new work attacking immigration and multiculturalism, and describing the acts of convicted Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik as “formal perfection … in their literary dimension.”

That bookish qualifier, says newsweekly L’Express in its critique of Millet’s new essay, “Éloge Littéraire d’Anders Breivik” (Literary Elegy of Anders Breivik), is a “gratuitous facade” for an otherwise “vindictive text” and thesis. Indeed, though Millet states he does not approve of Breivik’s murderous actions on July 22, 2011 that left 77 people dead, he does write the slaughter was “without doubt what Norway deserved.” The reason? Norway, Millet contends, allowed immigration, multiculturalism and the domination of foreign customs, language and religion to become such dominant influences that a self-designated defender of traditional society felt compelled to take decisive action.

(*) The period of the 1930s in France was one of extreme right wing political and anti-Semitic writing from authors like Céline and Robert Brasillach, who later collaborated with the German occupiers during WWII.

(**) The Belgian serial killer and child molester.

Published on September 11, 2012 02:34