John J. Gaynard's Blog, page 11

March 20, 2012

Good, if a little unusual, reading fodder: Rob Kitchin's review of The Imitation of Patsy Burke

It was very pleasant to read Rob Kitchin's review of The Imitation of Patsy Burke, an hour or so ago, the whole of which you can find on Rob's blog, The View From the Blue House, and which I will excerpt below.

It took me a little while to get into The Imitation of Patsy Burke - both the storyline and the style. The story is an in-depth character study and the story unfolds through the various voices in Patsy's head as it tries to reconcile the morning after with recollections of the afternoon and night before and the back story to the artist's life. At first, I found the style somewhat awkward and contrived, but as the story progressed the style made more sense and I got drawn further and further into the narrative and by the end I was truly hooked, staying up way past when I would normally shut a book and turn off the lights, devouring pages until I reached the end. And a very nicely resolved end it is too, both somewhat inevitable and slightly out of left field. Whilst Burke is a character for which one feels little sympathy, the characterization and its unfolding is very well done, with the story well layered. The voices in Patsy's head each have a distinctive voice and message and their bickering has an authentic tone (if voices in a head can have such a thing). The prose is nicely expressive throughout and is peppered with philosophical insights. If you like in-depth characterization, then The Imitation of Patsy Burke will provide good, if a little unusual, reading fodder.

The comment about the way in which Patsy Burke ends, as being "somewhat inevitable and slightly out of left field", really resonated with me. The brutal way in which I depicted such an anti-hero has had some readers looking at me askance and given others (who confound the writer with his anti-hero) a totally skewed impression of who I am now, as compared to who I used to be when I hung out with the man who "inspired" the novel. Sadly, the path that man took did lead to an inevitable, out-of-left-field conclusion, although not the same as the one that ends the novel.

Published on March 20, 2012 11:08

March 11, 2012

The five most read posts on my blog over the last month

Review of Alphonse Boudard's The Devil-May-Care Fighters

Alphonse Boudard tells of his adolescence and early manhood in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, during WWII and the German occupation. His main preoccupation, throughout the novel, is sex and the fact that he isn't getting enough of it, apart from a few standup sessions in doorways with a female colleague whose boyfriend has been forced into labor in Germany and who, Boudard surmises, is probably honoring the German woman whose husband is off fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front.

An Excerpt from The Imitation of Patsy Burke: Carla and Véronique

Patsy's doting Italian mistress Carla is becoming increasinly concerned by the way his erratic behavior is frightening staff in the gallery that sells his sculptures. She raises the matter with him in his office over the gallery and what he tells her takes her out of her comfort zone.

My Traitor & Home to Killybegs, by Sorj Chalandon

My discussion of the French writer Sorj Chalandon's two novels about Tyrone Meehan, a character based on the real life character Denis Donaldson. Chalandon's novels show how Donaldson's betrayal of his friends in the IRA was also lived as a tragedy by a young Frenchman.

Hannah's World: being a young Turkish-Jewish girl in occuped WWII Paris

Le monde d'Hannah--Hannah's World, has been described by Le Figaro as "a small miracle of a book" in its handling of a forgotten part of French, Turkish and Jewish history," which Mohammed Aïssaoui describes as, "...the tragedy of the Turkish Jews who lived, in occupied France during World War II, in the "little Istanbul" part of the 11th arrondissement of Paris. Aïssaoui, in his Le Figaro review, said, "In the first part of the book, the novelist marvellously brings to life the existence of these humble people whose only desire was to get a better life for themselves, without being noticed. Everything is here: the decor, the smells, the words that were spoken, and Hannah's mother's never ending refrain, 'Don't shame us'. Then come the humiliations, the narrow escapes, the deaths of close family members. Ariane Bois's knowledge of the history of the period is impeccable, but it never weighs on the story."

Luc Boltanski: Investigation, Police Procedurals, Enigmas and Conspiracies

The French sociologist, Luc Boltanski, has just brought out a new book, Enigmes et Complots, which is presented as "an investigation into investigations". In his book, he studies the associated arrivals, at the end of the 19th century, of first the police procedural and then the spy novel, and how they were both invented in reaction to the modern state's stranglehold on reality.

Alphonse Boudard tells of his adolescence and early manhood in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, during WWII and the German occupation. His main preoccupation, throughout the novel, is sex and the fact that he isn't getting enough of it, apart from a few standup sessions in doorways with a female colleague whose boyfriend has been forced into labor in Germany and who, Boudard surmises, is probably honoring the German woman whose husband is off fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front.

An Excerpt from The Imitation of Patsy Burke: Carla and Véronique

Patsy's doting Italian mistress Carla is becoming increasinly concerned by the way his erratic behavior is frightening staff in the gallery that sells his sculptures. She raises the matter with him in his office over the gallery and what he tells her takes her out of her comfort zone.

My Traitor & Home to Killybegs, by Sorj Chalandon

My discussion of the French writer Sorj Chalandon's two novels about Tyrone Meehan, a character based on the real life character Denis Donaldson. Chalandon's novels show how Donaldson's betrayal of his friends in the IRA was also lived as a tragedy by a young Frenchman.

Hannah's World: being a young Turkish-Jewish girl in occuped WWII Paris

Le monde d'Hannah--Hannah's World, has been described by Le Figaro as "a small miracle of a book" in its handling of a forgotten part of French, Turkish and Jewish history," which Mohammed Aïssaoui describes as, "...the tragedy of the Turkish Jews who lived, in occupied France during World War II, in the "little Istanbul" part of the 11th arrondissement of Paris. Aïssaoui, in his Le Figaro review, said, "In the first part of the book, the novelist marvellously brings to life the existence of these humble people whose only desire was to get a better life for themselves, without being noticed. Everything is here: the decor, the smells, the words that were spoken, and Hannah's mother's never ending refrain, 'Don't shame us'. Then come the humiliations, the narrow escapes, the deaths of close family members. Ariane Bois's knowledge of the history of the period is impeccable, but it never weighs on the story."

Luc Boltanski: Investigation, Police Procedurals, Enigmas and Conspiracies

The French sociologist, Luc Boltanski, has just brought out a new book, Enigmes et Complots, which is presented as "an investigation into investigations". In his book, he studies the associated arrivals, at the end of the 19th century, of first the police procedural and then the spy novel, and how they were both invented in reaction to the modern state's stranglehold on reality.

Published on March 11, 2012 06:53

March 7, 2012

Review of Alphonse Boudard's "The Devil-May-Care Fighters" about the occupation of WWII Paris

This is a book that should immediately be translated into English, preferably by a translator who has a good command of mid-20th century "argot", Parisian street talk. I decided to buy it as the result of reading a recent French book titled "Ainsi finissent les salauds", about the clandestine kidnappings and executions that took place in the first couple of months after the WWII liberation of occupied Paris. Boudard's novel "Les combattants du petit bonheur", published in 1977, was quoted at the beginning of many chapters of "Ainsi finissent les salauds". I see on the author's very brief Wikipedia page that the book's title is translated into English as "The Fighters of Haphazard", but it would be more accurate to translate it as "The Makeshift Fighters" or "The Devil-May-Care Fighters".

The book is presented as a novel, but it soon becomes clear that it's a work of autobiography, with most of the names changed. Alphonse Boudard tells of his adolescence in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, during the German occupation. He lived near the Place d'Italie with his grandmother, in a street full of very poor, but fairly contented people, with limited horizons and shabby clothes. Their lives revolved around life and gossip in their community, work--whenever they could get it, a slap-up meal from time to time and the conversation in the street cafés. At that time, a working class Parisian's street was his whole world and he rarely ventured outside it. The working class area where Boudard lived was strongly communist, but personally he couldn't give a damn about politics, or anything else whose truth he couldn't check out from his own experience.

His main preoccupation, throughout the novel, is sex and the fact that he isn't getting enough of it, apart from a few standup sessions in doorways with a female colleague whose boyfriend has been forced into labor in Germany and who, Boudard surmises, is probably honoring the German woman whose husband is off fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front. Boudard's political persuasion of the moment depends on the girl he is chasing, as he makes clear in a subsequent novel, "Le café du bonheur--Poor People's Coffee" (a Paris slang expression for making love, because it was the only sort of luxury the penniless could offer themselves).

Whether the girl Boudard wanted to bed was a Communist, Trotskyist, Catholic, a Judge's daughter, wife or whatever, Boudard would go along with her beliefs until he bedded her, and then revert to the usual anti-clerical and anti-political stance favored by working-class Parisians of old: distrustful of any educated barker, preferring to believe what they could hear and see with their own two ears and eyes. In "Poor People's Coffee" Boudard wrote a sentence that still makes me laugh out loud every time I think of it: "This isn't about principles. I don't have any."

Boudard's father left his mother soon after he'd made her pregnant at the age of 17. His mother is rarely mentioned. She doesn't live with him and his grandmother, and he makes clear, from the way he describes her whenever she does pop into their lives for a few minutes, after months' of absence, that she probably makes her living as a prostitute. After the French capitulation in June 1940, Boudard tried to leave Paris by bike, with a group of friends. But they only got as far as Orleans before they had to turn around and head back for Paris.

The winters of the occupation were deadly: the cold and the vermin, combined with lack of food and basic amenities, killed off many poor Parisians. Boudard was an honest juvenile delinquent. He saw himself as only fighting for survival, and he would never play a dirty trick on a member of his own gang of friends or one of the older people in the area. His first theft from the Germans, a bicycle, was stolen from him a few hours later, by the 21 year old elder brother of one of his friends, who was notorious for making love to a woman grocery shop keeper three times his age, so that he could get his hands on black market food.

Boudard worked as an apprentice type-setter in a printing works. There he met the men who enrolled him in the resistance. He left Paris with a friend of his own age to join a group of resistants in the countryside, but lost his way and arrived late at the meeting point, a remote farm. Struggling through the woodlands to get to the farmhouse, Boudard and his friend heard volleys of shots. A man comes rushing towards them and takes them to hide in his house. The forty young men they were going to join up with had been massacred by the Nazis and the French Militia. Boudard and his friends dug holes in the ground, covered themselves with branches and leaves and hid out until the Militia stopped searching the woods.

He participated in an attack against the Germans, managed to seize some of their arms, and then headed back to Paris, where he engaged in clandestine activities until his unit of the Free French Fighters, which was made up of friends from his gang, was given the task of liberating a part of the Latin Quarter. Far from the glorious story about the French resistance fighters made up after the Libération, Boudard wrote honestly about the shambles that he found instead of a disciplined fighting force. If the Germans hadn't already decided to leave, there was no way the makeshift fighters would have managed to dislodge them. As more and more opportunists joined the FFI to exact revenge on their neighbors, kill collaborators--many of whom were subsequently proven to be innocent, and steal what they could, the resistance movement in Paris was increasingly in danger of becoming an out and out shambles.

Boudard describes how young men from a rival gang, barely out of their twenties, join the Petainist and, ultimately, pro-Nazi French Militia. He mentions frequently in the "novel" that it was only by luck that he wasn't forced to join the Militia himself.

One of the young Militia men from the other gang, Stéphane, who had gone to primary school with Alphonse, is "miraculously"--writes a skeptical Boudard, transformed into a leading figure in the Resistance movement in the first days of the Libération. In Fresnes prison in 1948, Boudard meets Stéphane's best friend, who had stayed with the Militia to the bitter end, and been found guilty of collaboration, and of torturing and killing members of the resistance movement. He was waiting to be taken out and shot at dawn. In spite of everything the Militia had done, Boudard couldn't find it in himself to hate the man, because he knew how close he'd come to being in his shoes instead of his own.

Towards the end of the novel, he gives details of of how "resistants" who had come late to the game dragged women out into the streets, stripped off their clothes, cut off their hair and branded them for sleeping with Germans during the occupation. He also mentions the renegade communists who became as bad as the Nazis, when they transformed the Dental Center in the Avenue de Choisy into a torture and killing center. The book "Ainsi finissent les salauds" researched some of the illegal killings committed after the Liberation, and confirms the events Alphonse Boudard describes in his novel, although, with the benefit of hindsight, it fills in details that Boudard couldn't have known at the time.

When Boudard met the Militia man waiting to be executed, he was himself being held in the prison for petty crimes committed after being demobilized from the French Army, which he had joined soon after liberating the Place Saint-Michel with the small group of buddies he'd recruited to fight with the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). He spent a good part of the next 15 years in Prison, where he began to read to counteract the boredom, and then to write. His first novels were published at the beginning of the 1960s and found immediate success in France, although many of them are now out of print.

The novel ends on a sad note. The beautiful young judge's daughter with whom Boudard falls in love at first sight, when he is installed in a fifth-floor apartment, from which to rain down Molotov cocktails and machine gun fire on German trucks and tanks entering the Place Saint-Michel, at first flirts with him but then spurns his advances. When the men of General Leclerc's 2nd Armored Division, and the clean, healthy and handsome young American soldiers finally enter Paris, she leaves behind her the 19 year old, unwashed and unsophisticated French street fighter and, accompanied by her beautiful mother, dances and screws the night away with the real liberators.

Published on March 07, 2012 15:09

March 2, 2012

An Excerpt from The Imitation of Patsy Burke: Carla and Véronique

"Why couldn't you just have accepted to make her

pregnant?

In the office you began to talk to Carla mechanically,

and you imagined looking at yourself through her eyes.

To your surprise, she didn't seem to have a good

opinion of you. She was still attracted by your scarred face and caveman good

looks, and your firm chin, and your genius as a sculptor who had hauled himself

out of the English cum Irish settled working class by your own bootstraps, but

as a man you were a complete piece of shit with whom, unfortunately, she had

fallen in love.

She told you that your role, as a sculptor, in

Jean-Louis's corporation induced stress of a truly unmanageable level in its

employees. They all depended (and probably still depend) on your saleable

output to put bread, wine and cheese on the table and to pay for their children's

holidays: once a year, to the Val d'Isère, to ski during the first school

vacation of the year; and once a year to Sardinia or Mauritius, during the

summer vacation period. Furthermore, the stress had increased since your behavior

had become no longer merely violent but uncontrollable. The kidnapping had done

something to you, had broken something in you. People had seen you down in the cafe,

looking at the wall like a madman.

You told Carla you deeply regretted that giving

Jean-Louis a few kicks, a tap on the chin, and then a kick up the backside, in

front of all his staff, that day when he had called the whole company together,

had encouraged, among simpleminded, salaried employees, people to whom you

would never normally be violent because they had never done anything to merit

that sort of treatment, the emergence of the rumor that you had a penchant for violent

behavior.

No, Patsy wasn't the type of man to have a penchant

for anything, except for good sex and a couple of drinks before and after a

hard day's work. And then she reminded you of how you had screamed at

Jean-Louis, as you stood over him, at the exact place where he had fallen to

the floor, and of that last kick you had given him in the testicles. Didn't you

realize how dangerous it could be to kick a man there?

'But I only did it once,' you said.

'You nearly did it again this morning,' she replied.

'What does that damned lawyer get paid for, if he

can't even prevent me from attacking my good friend, Jean-Louis?'

You told Carla that you had simply wished to get the

message across, the message that you no longer wished to pay through the nose for

Jean-Louis's worthless services. The employees, by themselves, were unsatisfactory

but they might have been able to do a halfway decent sort of job if it weren't for

the crap system of Harvard type management Jean-Louis had put in place.

Why couldn't he have stuck to a traditional French management

style? If Jean-Louis couldn't get the organizational structure, culture and

climate of the art gallery right, there was no alternative. He, Patsy, would

have to fire more than half of the back office staff and all of the new, crap Asian

sculptors.

Thus, you explained to Carla, it was all Jean-Louis's

fault if the sales and administrative staff were going to lose their jobs. Some

of them had, of course, toadied up to the new Korean sculptors whom Jean-Louis

had taken on, but Mr. Patsy Burke was too big a man to let his rational brain

be overwhelmed by jealousy of another sculptor, or even by legitimate sentiments,

such as grievance at a growing lack of respect for him as he walked through the

gallery. Patsy dated that lack of respect back to the time Jean-Louis had taken

on his first second-rate Japanese sculptor.

Had Jean-Louis admitted his own guilt? Had he admitted

to the staff that half of them were going to be fired because of his poor

management methods? Had he owned up to the fact that he was an ineffective

gallery owner, who had dilapidated the success brought to him on a plate by Mr.

Patsy Burke, who was not only the best sculptor in his stable of artists, but

in the whole of f**king France?"

"She did not reply to your loaded questions, and just

went on pulling wispy thoughts out of her mind, like pairs of empty nylon

stockings from pink cellophane wrapping, thoughts that had no relevance to what

was going on inside your own head.

Well, so be it. That was modern business. There was

nothing you could now do to lessen the tragedy that you were the only available

business mind in the company, the only man capable of reorganizing it, making a

go of it, after the disastrous financial results that resulted from Jean-Louis's

eccentric style of management, and therefore you might even have to give him

another good kicking and to throw many idle staff out onto the streets, it

might in fact be three quarters of them, not just a half.

Nonetheless, you sincerely wished to be liked, and your

long-term objective was, indeed, to become liked again; to be perceived as a

kindly, measured, reasonable human being, who could shed light, and dry humor,

wherever the ebb and flow of success, as demonstrated by an increase in cash,

or other liquid assets, would eventually lead you.

Yes, you had tried to act the business-man and, while

we're on the subject of acting, you reminded Carla that Véronique had once acted

as your secretary, for a few weeks. You had of course given her a horizontal

promotion--what a beautiful French phrase that is!--and for ninety-nine percent

of the time the play acting between the two of you had passed off well, if only

from a sexual point of view. You had not taken her in, and she had not taken

you in, any other way than physically. But the other one per cent of the time,

that is the one percent that must have stuck in Véronique's memory, and which,

apparently, she had mentioned to Carla, was due to what Véronique called the

extravagance of his ideas. But who was Véronique to judge either the extravagance

or the feasibility of Patsy's ideas? Had she, or any other person in the

gallery, ever taken an idle thought and a block of marble and turned them into

a one million dollar sculpture as Patsy had done? That poor idiot, Jean-Louis,

had of course let himself be fooled by her, thus the problems he was having

with his wife.

'Véronique, bring me the accounts books,' you screamed.

She was not in the office, but you knew she probably

had her ear flush to the door, eavesdropping. That wild scream shook Carla up,

the poor dear. She rolled her eyes to the ceiling, in that irritating way women

will never realize gives the whole game away, and she looked at you with hate

in her eyes.

As you waited for your former secretary to hurry back

into the office, you observed Carla closely. She regained control of herself,

and managed to hide the look of hate. Véronique arrived, out of breath. You

looked at the accounts books. You did not understand a single column.

You said, 'Usually when I feel I'm going to come

across a particularly loathsome miscalculation, a strategic error or a shoddy

piece of thinking, I flare up, Véronique, and if I have to shout harshly, it is

because it's the only way I can get you to understand how seriously I take this

business of accounting! But that is not the only reason I screamed at you to

come in here, it is also because of all the pain you are making Jean-Louis's

poor wife go through. Can't you see that the man is too eccentric to

concentrate on more than one task at a time? He should be concentrating on

business at the moment, not on getting his end away with a woman who has

already been treated very, very kindly by the gallery inasmuch as she has

already been shagged by its senior sculptor, on more than one occasion.

You heard Carla's shocked intake of breath as you

revealed again that you had had a sexual relationship with Véronique, and then you

shouted at her harshly, accusing her of being needlessly jealous, using words

that would need much more than ninety-nine percent of your effort, thereafter,

to make them be forgotten.

The two women were now taking you seriously. You told

them you could not understand why people who have gone through some of the

world's most advanced and expensive national educational systems managed to

have sexual problems with their bosses, or secretaries, especially when they

should be demonstrating such routine professional

behavior as following administrative procedures blindly, and ensuring

transparent earnings before interest and tax, while keeping a lid on

Jean-Louis's expenses, and not contributing to the flow of hateful rumors about

their colleagues, most notably the senior sculptor.

Okay, let them go out for a few drinks together,

participate in ritual excesses at the annual Christmas office party, and fuck

the asses off each other once a year, that is the way life should be lived, but

why did they have to start taking themselves seriously, falling in love,

getting jealous, screwing up a good business because they had taken their eye off

the ball?

You had told Jean-Louis, on numerous occasions, that

you could not suffer employees who let computers think for them, especially

when they then expected you, Patsy, to praise mediocre, glossily printed and

lavishly colored three dimensional bar charts produced by the technology. What

would happen to the gallery if you suddenly decided that you weren't going to

sculpt with your own two hands but turn the work over to a fucking piece of

software, for God's sake?

You told the two women that even in your fighting you

had always been straightforward, and never racist. As a person who had been

ostracized yourself, how could you hate a man because of his religion or the

color of his skin? The only reason you had ever hit an African or a Chinese was

because you needed to hit someone, and a black man or a yellow person was the human

being most available. Until you were about twenty-five, you barely stopped to

even study the nose on a hostile face, never mind the color, before you

attempted to smash it. You never gave a damn about the eye-turning fear, or the

pain or the battered emotions of anyone you hit, and, to your credit, you never

had a feeling of revenge against any man who bettered you. The important thing

was to thrash the other man before he could thrash you, whatever his color or

religion, to get the jump on him through the element of surprise, and to throw

yourself at him with both boots before the bastard could make use of his fists.

What was wrong with that?"

My novels, The Imitation of Patsy Burke and Another Life , can be purchased from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr and Amazon.de, in either print or electronic versions. You can find them by following any of the links below:

Amazon.com (Amazon in the United States)

Amazon.co.uk (Amazon in the U.K. and Ireland)

Amazon.fr (Amazon in France)

Amazon.de (Amazon in Germany)

Print and electronic versions can also be purchased from Barnes & Noble in the United States, by following this link: barnesandnoble.com

But Amazon and Barnes and Noble are not the only outlets. You can buy electronic versions of my books, suitable for many different readers, such as iPhone, Sony or Kobo from SMASHWORDS.

Published on March 02, 2012 11:33

February 23, 2012

New lease of life for 500.000 French Books still in copyright but no longer in print

There is nothing more frustrating than to look for a book which is still in copyright, but find that it is out of print. If the book was published fairly recently, you may strike lucky and pick up a used copy in a second-hand bookstore, or on the Amazon or Abebooks websites, but if it was first published 20 or 30 years ago you just have to accept you will probably never read it, unless you live for the next forty years, and can wait for it to fall into the public domain.

Portrait of Laurence Sterne.

However, as Laurence Sterne, once told us, in his now out of copyright, and thus available A Sentimental Journal through France and Italy, it seems that this may now be a matter better ordered in France.

In today's Les Echos financial daily, there is an article that explains that the legislators of the French National Assembly, based on a recommendation from the country's Minister for Culture, have decided to make French books that are still in copyright, but out of print, available for sale once again. This is a matter that can also be of interest to authors who have been translated into French, and whose books are now out of print in France, or publishing houses or agents who look after the copyright of authors who have been translated into French over the past 70 years.

Here is what Les Echos had to say this morning about the new law:

You can read the whole Les Echos article (in French) here:

Nouvelle jeunesse pour 500.000 livres épuisés mais pas encore libres de droits

* (The CFC's website exists only in French, but Sofia can be consulted in both French and English versions.)

Portrait of Laurence Sterne.

However, as Laurence Sterne, once told us, in his now out of copyright, and thus available A Sentimental Journal through France and Italy, it seems that this may now be a matter better ordered in France.

In today's Les Echos financial daily, there is an article that explains that the legislators of the French National Assembly, based on a recommendation from the country's Minister for Culture, have decided to make French books that are still in copyright, but out of print, available for sale once again. This is a matter that can also be of interest to authors who have been translated into French, and whose books are now out of print in France, or publishing houses or agents who look after the copyright of authors who have been translated into French over the past 70 years.

Here is what Les Echos had to say this morning about the new law:

The act concerning literary works that are no longer available, but which have not fallen into the public domain, was due to be voted into law at the National Assembly yesterday evening. It will provide for a co-operative system of digitization and distribution of 500.000 books.

This is in spite of the petition launched a few days ago by some 800 writers who came together to protest that the law will constitute "pure violation of copyright."

The plan is to bring back to life hundreds of thousands of books that can no longer be found in bookstores, but which have not yet fallen into the public domain (works fall automatically into the public domain in France only seventy years after the death of the author).

Under the new law, these books will be digitized and put on sale, and the corresponding copyright will be subject to a form of co-operative management. To ensure that royalties are fairly distributed to authors and publishers, the task will be entrusted to two organisations: the CFC (Centre Français d'exploitation du droit de Copie) and the SOFIA (Société Française des Intérêts des Auteurs de l'écrit).*

A first in Europe

"This mechanism is a first in Europe. It will again make accessible thousands of forgotten works", said Christine de Mazières, spokesperson for the French Publisher's Association (SNE). The French National Library will help in the digitization of the literary works of most interest to the public. About 500.000 books published during the 20th century are presently being selected. There will be a publicly available database of the works.

The cost of the operation, estimated at €30 million, will probably be funded by the national "big loan" for innovative projects that was lauched by France in 2010. "The application is under review and should be finalized soon," said Christine de Mazières. In response to the concerns expressed by some authors, the spokesperson of the the French Publisher's Association, said that the new law makes provision for any author who does not wish to participate to opt out of the co-operative management system, and at any time. "Co-operative management is well suited to this project. The individual management of the rights to so many works would be extremely long and tedious, especially with regard to the small number of sales that will be generated," she said.

But the only way for publishers to opt out of the system will be for them to commit effectively to make the works, that are of interest to the project, once again available for sale.

You can read the whole Les Echos article (in French) here:

Nouvelle jeunesse pour 500.000 livres épuisés mais pas encore libres de droits

* (The CFC's website exists only in French, but Sofia can be consulted in both French and English versions.)

Published on February 23, 2012 03:01

February 20, 2012

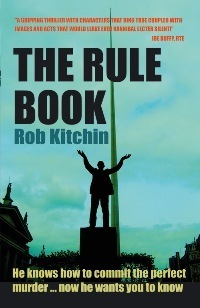

Review of Rob Kitchin's THE RULE BOOK

The Rule Book is an intricately plotted police procedural set in and around Dublin, in the atmosphere of impending social and political failure that eventually led to the Celtic Tiger having its head unceremoniously expelled from its ass by the 2008 banking crisis.

The book was published in 2009, but Kitchin's 'Acknowledgements' on the final page are dated August 2008. Thus, he was probably writing the story in 2007 and the beginning of 2008. The novel shows how contemporary crime fiction, as opposed to historical crime fiction--which has the benefit of hindsight--can, in the hands of a prescient writer, capture the most salient elements of a corrupt state, although at the time of writing the writer doesn't know what is going to happen in a few months' or a few years' time.

Detective Superintendent Colm McEvoy is put in charge of the hunt for a serial killer who, after every murder, leaves behind a deliberate set of clues, but in never enough detail--until it is too late. McEvoy is a decent man, a person whose human failings are numerous, and whose grieving for his dead wife, prevents him from functioning effectively, either as father or policeman. These traits reminded me of the police officers to be found in the crime novels of Henning Mankell and Arnaldur Indridason. A big difference between Kitchin and Mankell or Indridason is that Kitchin refuses to tie everything up neatly with a pink bow at the end of the book.

You want Colm McEvoy to succeed but, at every turn of Kitchin's cruel handling of him, he screws up even worse than the time before, and the reader becomes more and more convinced of what McEvoy admits himself, that if the killer is ever unmasked it will only be by accident. Kitchin invites you to to witness McEvoy being used as a convenient scape-goat by his superior, a commanding officer who says he is there to protect him but who is, in reality, a cynical placeholder. Time and again, McEvoy is taken off the case, only to be put straight back on it, as his commanding officers (his boss and his boss's boss, right up to the Minister for Justice) realize that, if they no longer have a fall-guy, they will have to take the responsibility for failure themselves. Colm McEvoy is also undermined throughout the book by a Detective Inspector named Charlie Deegan, who brought to mind the way in which another self-serving Charlie, who went under the surname of Haughey, undermined the then solid underpinnings of the Irish State with which he was entrusted. Deegan's conduct, undermining Colm McEvoy at every opportunity, gets him taken off the case, once, but people in positions of power are ready to pull strings to reinstate him, and he too is kept on until it is too late.

Kitchin's descriptions of the hounding of Colm McEvoy and his family, by journalists from the Sun, and the influence the press had on figures of power in Ireland (terrified of having people from abroad scrutinize their incompetence) foreshadows the well-deserved wave of public disgust in the U.K. that was soon to hit News International and all who sail in her.

Kitchin dissects an Ireland where men who get into positions of power--shown here in the shape of the country's police force, but not limited to them--suffer from a lack of expertise in a field they are supposed to master; spend an inordinate amount of time trying to please the media; and pay more attention to form than substance. Colm McEvoy's boss is more interested in the state of his clothes, and how he will appear to the television cameras at the frequent press briefings, than he is in the details of the murders McEvoy has to investigate. People in authority refuse to shoulder the responsibility that should be the corollary of their well-paying jobs; push important decisions down the chain of command until they find the guy who will take the fall; plan every action in the way that will best cover their asses, and, most tellingly of all, have no idea of what needs to be done to thwart sophisticated enemies, whether they be serial killers, (or, by extension), financial whizz-kids, who are left free to run rings around the stately, plump, prevaricating authorities.

Through the prism of the Irish police force, the novel depicts a whole country that doesn't have the smarts to understand any of the challenges it has brought on itself by moving away from a rustic set of values towards items of interest dear to the gutter press: sensationalism, human weakness, the wreckage resulting from the availability of cheap and plentiful booze and drugs and the rivers of teenage vomit and drunken violence running through Dublin's O'Connell Street late on a Saturday night.

The novel points out that there has never been a serial killer in Ireland. Until four years ago, the Republic of Ireland had also not had a banking crisis that beggared belief when it happened, but for which all the signs and clues had been there for perspicacious economists like Morgan Kelly. Morgan Kelly, a man who specialized in the economics of Medieval Iceland, realized what was about to hit Ireland when he discovered, nearly by accident, that neither the Banks nor the Government were following their own basic economic rule book.

Colm McEvoy, in some ways, brought to mind the tragic figure of Brian Lenihan junior, the Irish Minister for Finance, and especially the night he was left alone to fend for himself, a distraught figure wandering the back roads of Ireland, charged by his political, banking and property-developer masters and colleagues to find a silver-bullet solution to the Irish banking crisis, a fall guy who was immediately blamed for the only remedy he could find, the disastrous state guarantee of the Irish Banks.

At the time of the novel, McEvoy is shown as a symbol of the decent people who were trying to hold Ireland together in face of an unprecedented assault on its identity. Too busy at work to get a regular wash, in dire lack of sleep, wearing a disheveled suit, now two sizes too large for him since he began to grieve for his late wife, he is obviously not up to the job he eagerly takes on. All he has going for him is a basic level of competence and a streak of honesty, but he is no match for the evil mind of the sophisticated killer, who spies on him and taunts him with clues which will eventually show that the center of everything rotten lies in what has constituted a pillar of the Irish State, ever since its founding: Maynooth.

Rob Kitchin leaves the reader with the feeling that what he or she has understood is pretty bad, but worse is still to come. Any other mind like the serial killer's--determined, sophisticated and evil--will also be free to run rings around the plodders to whom it arrogantly gives all the clues. The authorities will be incapable of catching the most powerful criminals in their midst, even when the wrongdoers disregard their own rules and make basic mistakes or, as the serial killer does at one moment, hold the door open for them while wearing a ridiculous disguise.

The book is a page-turner and will give any discerning reader of crime fiction extremely good value for his or her money.

Published on February 20, 2012 09:09

February 16, 2012

Luc Boltanski: Investigation, Police Procedurals, Enigmas and Conspiracies

The French sociologist, Luc Boltanski, has just brought out a new book, Enigmes et Complots, which is presented as "an investigation into investigations". In his book, he studies the associated arrivals, at the end of the 19th century, of first the police procedural and then the spy novel, and how they were both invented in reaction to the modern state's stranglehold on reality.

Below are a couple of excerpts from an interview with Luc Boltanski in today's edition of Libération.

LIBERATION: Enigmas and Conspiracies deals with a critical moment, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, which saw the appearance of investigative literature in very different genres. How do you explain that?

BOLTANSKI: It was the result of a new sort of anxiety, of a new way of looking at the world. That period corresponded to a sort of apotheosis in the life of the Nation-State, an entity that was trying, with the help of hard science and the social sciences, to develop a God-like project: to establish a stable reality in a given territory for a given population. In other words, the State was trying to construct its own reality... Investigative literature arrived at the moment when people began to understand that it was impossible to stabilize reality, when reality began to disappoint expectations. In times of stability, there is no need for investigations.

LIBERATION: The appearance of the police procedural offered you an opportunity to investigate the historical phenomena you have in mind. You choose to compare English and French police procedurals. Why?

BOLTANSKI: If a link exists between the Nation-State and the birth of the police procedural, we should be able to see that different forms of literature are linked to different types of State organization. Sherlock Holmes has been the subject of a lot of analysis, for example by Umberto Eco or Carlo Ginzburg. Holmes is a genius at deductive analysis, confronted by criminals who are themselves, if we take the case of Moriarty, geniuses at calculation. With Sherlock Holmes, everything happens in a world of social harmony, the liberal-minded England of that time, a world in which the dominant class, the aristocracy, was not in conflict with the middle classes. Different social classes are very present, but they are handled as the natural order of things. Social equilibrium is a matter of social calculation, and the State, which remains in the background most of the time, intervenes only when somebody makes a mistake about his ability to calculate for himself.

LIBERATION: You have used Simenon to analyse the French State.

BOLTANSKI: The case of France, as it appears in Simenon's stories, is very different. France had been experiencing low-level civil war, since at least 1792, interspered by very tense, high-level periods such as 1848 or during the Commune. There was permanent tension between the social classes, in a universe which was far from being liberal-minded. Parliament was considered to be at the very heart of the corruption that plagued the country. The only source of stability was the administration (the civil service). The vision of France we can extract from the Maigret novels, is a mosaic of different social milieux which each possessed their own norms, with government bodies only intervening, like colonial powers, whenever there were murders and when they couldn't avoid getting involved.

Holmes found himself in a pragmatic social situation, that provided signs and clues, and his investigations were centered around analysis.... Maigret, on the other hand, does not search for clues, he doesn't make calculations about situations, he immerses himself in social milieux exactly as if he were a sociologist in the French tradition of sociology; he tries to put himself inside the skin of the suspect he is pursuing.

LIBERATION: Apart from the differences, these two types of novel share one characteristic: the doubling up (or duplication) of the hero...

BOLTANSKI: When the police procedural invented the detective, it duplicated the the investigate function, between a policeman who represents the State--and who is generally shown as a half-witted idiot limited by legal niceties--and an amateur investigator who, in the case of Holmes, finds himself suitably located to sort out the affairs of high society, while keeping them in the private sphere.

For Maigret, this doubling up takes the shape of a split personality. That is one of the principal psychological underpinnings of his novels. On one hand, you have a civil servant, who does his duty as a policeman, and on the other hand, a man who thinks for himself, who decides, for example, that it's not very nice to send a man to the guillotine and who decides that, sometimes, it's better to let the criminal die a natural death.

LIBERATION: What did the spy novel bring, when it came along a while later?

BOLTANSKI: In the police procedural, the pleasure given to the reader comes from a sort of game with reality. A little like those pictures for children which change shape depending on the child's point of view. This reality which seems so stable is not, in fact, what it seems. The police procedural showcases the tension between a local reality, which is seemingly stable, and facts which shake the confidence we can have in that reality.

In the case of the spy novel, it is the State itself, and not just a local reality, or a village, which is destabilized. Movements and flows of unknown origin imperil the integrity of the whole territory. In the global space of a country, not one single thing can be above suspicion, even at the highest level of the State, where moles can now be found. Beginning with WWI, the spy novel became one of the pillars of nationalism and, at times, anti-Semitism....

You can read the whole interview (in French) with Luc Boltanski in Libération, but you'll have to pay for it! :

Enquête de stabilité- Libération

Published on February 16, 2012 09:17

February 3, 2012

Clandestine communist kidnappings and executions in liberated Paris

Jean-Marc Berlière and Franck Liaigre have followed the publication of their 2007 book, "Liquider les traîtres - Liquidate the Traitors: the hidden face of the French Communist Party between 1941 and 1943", with "Ainsi finissent les salauds--Putting an End to the Bastards: clandestine kidnappings and executions in liberated Paris."

Under the heading, "The Bloody Liberation", the weekly current affairs magazine, Le Point, under the pen of François-Guillaume Lorrain, has given a good introduction to the book in this week's edition.

"At the beginning of September, 1944, the Seine was no longer a quietly flowing river, but carried dozens of corpses along its length. The dead all resembled each other in a a couple of respects: they all had a bullet in the back of the head, and a cement block hanging from their necks. They had something else in common: they had all been executed by the FTP, the French resistance fighters known as the "Free Shooters". The Libération is a sacred moment in our history. But Berlière and Liaigre are historians. Their job is to root through the archives.

The two historians zoom in on one address, the Dental Institute at 176, Avenue de Choisy, the headquarters of the communist FTP, from August 22 to September 15, 1944. It was a torture center, a killing center and it bears comparison with what happened in the French Gestapo torture center in the Rue de Lauriston and the Nazi Gestapo intelligence offices in the Rue des Saussaies*.

There, in blood, in an atmosphere of summary justice, people were made to atone for the sins of Petainism, in a total lack of respect for the Republican legal system which had just been restored. The historians have found the executioners. And the victims. Not really notorious collaborators: a former socialist member of parliament, a pathological liar, a washerwoman, former Free Fighters... People died for the slightest reason. Some survivors have testified. The executioners were amnestied, in the name of... The Resistance. Other "killing machines" existed in other places. But, this Institute... Another black page in our history was written in the Avenue de Choisy; where one of the regulars was a certain Marguerite Duras."

* "Rue des Saussaies figures in the novel The World at Night by Alan Furst, as the location of the headquarters of the Nazi Gestapo intelligence offices." (information from Wikipedia).

Published on February 03, 2012 11:36

Clandestine Communist kidnappings and executions in liberated Paris

Jean-Marc Berlière and Franck Liaigre have followed the publication of their 2007 book, "Liquider les traîtres - Liquidate the Traitors: the hidden face of the French Communist Party between 1941 and 1943", with "Ainsi finissent les salauds--Putting an End to the Bastards: clandestine kidnappings and executions in liberated Paris."

Under the heading, "The Bloody Liberation", the weekly current affairs magazine, Le Point, under the pen of François-Guillaume Lorrain, has given a good introduction to the book in this week's edition.

"At the beginning of September, 1944, the Seine was no longer a quietly flowing river, but carried dozens of corpses along its length. The dead all resembled each other in a a couple of respects: they all had a bullet in the back of the head, and a cement block hanging from their necks. They had something else in common: they had all been executed by the FTP, the French resistance fighters known as the "Free Shooters". The Libération is a sacred moment in our history. But Berlière and Liaigre are historians. Their job is to root through the archives.

The two historians zoom in on one address, the Dental Institute at 176, Avenue de Choisy, the headquarters of the communist FTP, from August 22 to September 15, 1944. It was a torture center, a killing center and it bears comparison with what happened in the French Gestapo torture center in the Rue de Lauriston and the Nazi Gestapo intelligence offices in the Rue des Saussaies*.

There, in blood, in an atmosphere of summary justice, people were made to atone for the sins of Petainism, in a total lack of respect for the Republican legal system which had just been restored. The historians have found the executioners. And the victims. Not really notorious collaborators: a former socialist member of parliament, a pathological liar, a washerwoman, former Free Fighters... People died for the slightest reason. Some survivors have testified. The executioners were amnestied, in the name of... The Resistance. Other "killing machines" existed in other places. But, this Institute... Another black page in our history was written in the Avenue de Choisy; where one of the regulars was a certain Marguerite Duras."

* "Rue des Saussaies figures in the novel The World at Night by Alan Furst, as the location of the headquarters of the Nazi Gestapo intelligence offices." (information from Wikipedia).

Published on February 03, 2012 11:36

Gianrico Carofiglio, Italian Legal Thriller Author: Voluntary Witness for Involuntary Witness?

A couple of French friends have been lauding the Italian writer Carofiglio to me for the past couple of years. I finally got around to reading one of his legal thrillers, Involuntary Witness, and it was as good as I had been led to believe.

The novel is about as far as you can get from the hard-boiled crime genre. Carofiglio's defense lawyer, Guido Guerrieri, spends most of the time at the restaurant or on the beach, mulling over his failed marriage and his mis-spent youth, avoiding women while being fatally attracted to them, sometimes letting himself be led against his better judgement into what he thinks is free love, before he finds he literally has to pay for it. What you see is a man going about his life, experiencing many incidents of everyday life which have no bearing on the crime he has been engaged to solve, but which give a rounded portrait of a forty-year old Italian lawyer who considers he has a job not much different to any other. The sights, sounds and questions that emanate from the, outwardly, laid-back sort of life to be enjoyed in Italy pepper the novel in such a way as to keep you turning the pages.

In a manner reminiscent of the old Perry Mason series on TV, most of the action takes place in the courtroom. Having done nothing much since he was first contacted to defend his client, Guido Guerrieri, Carofiglio's defense lawyer character walks into court with no evidence to counter the charges against his Senegalese client, accused of killing a child he had befriended. But, he pulls one rabbit after another out of the hat until the innocent African walks free. Everything is based on intuition, not on the painstaking procedures of forensic science. And that makes a pleasant change from all the gore and sadistic dissection to be found in many recent crime novels.

On the French website Newsstart, Valentine Patry described an interview with Carofiglio. Below is my very free translation of a few parts of it:

"Writer, anti-mafia prosecutor and senator, Gianrico Carofiglio has an unusual background, an unusual personality and an outstanding and undeniable literary talent. Author of 12 novels and essays translated into 18 languages, he has sold over 2 million books.

Meeting with a writer of novels is more fun than you might think.

Swaggering, proud, impressive are the first impressions you get from meeting Carofiglio ...

We see the magistrate, the politician with his immaculate white shirt and nice wristwatch. But when you see the gray sneakers he is wearing, the superstar becomes human. He is very handsome. Short hair slightly graying at the temples, tanned, svelte and smiling. He speaks to us and you soon realize that, on top of everything else, he is nice. His jokes makes you laugh.

In his clear voice, he explains that he is often asked, "why the magistrate became a writer, but it would be more worthwhile to find out why a boy who wanted to become a writer became a magistrate"

It is surely the many hats he has worn--judge, senator and writer-- that have made his works unique and so realistic. He says he has never been directly inspired by one of the real-life incidents he encountered in his career as a magistrate and an anti-mafia prosecutor. His imagination crystallizes and condenses everything, but he admits that his professional experience is an asset for solving serious legal puzzles.

It is probably the "realistic aspect" of his work that has persuaded so many film makers to translate his novels into the language of the seventh art. But far from being pale translations, these film adaptations give new life to his art and breathe new life into his career as a writer, boosting his fame still higher. Carofiglio is nothing if not surprising. He is so engaging that it is difficult to imagine that this gentleman poet was also an anti-mafia prosecutor, and a senator before he began to write novels in the "legal-thriller" vein. Finally, you end up thinking that, although you see the shirt first, he bears more resemblance to his sneakers..."

Published on February 03, 2012 02:53