Walter Coffey's Blog, page 193

January 23, 2013

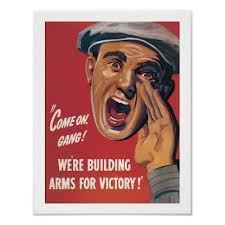

FDR’s Illicit Victory Program

In July 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated the “Victory Program” to fight World War II. Advisors began providing Roosevelt with estimates on troop mobilization, industrial strength, and logistics to defeat enemies in Europe and Asia. There was only one problem: the U.S. was a neutral country that had not declared war.

Japan had not yet attacked Pearl Harbor, and Germany’s official policy was not to attack U.S. shipping on the seas. Yet the Roosevelt administration violated neutrality laws and defied public opinion by preparing for a war that most Americans did not want.

Japan had not yet attacked Pearl Harbor, and Germany’s official policy was not to attack U.S. shipping on the seas. Yet the Roosevelt administration violated neutrality laws and defied public opinion by preparing for a war that most Americans did not want.

The Quest for Neutrality

In the 1930s, most Americans had bitter memories of World War I and the flawed peace that came from it. As such, when Adolf Hitler’s Germans annexed European countries, Benito Mussolini’s Italians invaded Ethiopia, and Emperor Hirohito’s Japanese attacked China, a poll revealed that 70 percent of Americans wanted no part of the struggles. This left it to President Roosevelt to change the public’s mind, and he did so through both legal and illegal means.

Reflecting public opinion, Congress passed a series of neutrality laws to avoid the circumstances that had prompted the U.S. to enter the First World War. These laws warned U.S. citizens that they traveled on warring nations’ ships at their own risk, and prohibited U.S. businesses from providing war equipment, loans, or credit to any warring nation. The U.S. could only provide non-war equipment to warring nations, and only on a “cash-and-carry” basis (i.e., the warring nations had to pay cash and carry the goods on their own ships).

When Japan and China went to war in 1937, Roosevelt authorized supplying China with war equipment in apparent violation of the neutrality laws. But Roosevelt had found a loophole: the laws could only be enforced when the president acknowledged that a state of war existed. Thus, Roosevelt simply refused to acknowledge that Japan and China were at war.

America First

Roosevelt’s support of the British resistance to Germany angered many Americans who sought neutrality and non-intervention. As a result, the America First Committee (AFC) was formed in the spring of 1940 to protest Roosevelt’s non-neutral policies.

Historians have often overlooked the many prominent Americans who either belonged or contributed to the AFC: writers Sherwood Anderson, e.e. cummings, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis; former President Herbert Hoover; future Presidents Gerald Ford and John F. Kennedy (Kennedy wrote the AFC a letter stating that “what you are doing is vital”); famed aviator Charles Lindbergh; and Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of former President Theodore Roosevelt. At its peak, the AFC had about 850,000 members, along with millions of sympathizers.

In response, Roosevelt ordered the FBI and the IRS to investigate member activities. Telephones were tapped, and some AFC members faced grand juries. Roosevelt attempted to discredit the AFC by claiming that “Nazi agents” had infiltrated the group, but no evidence was obtained to prove the allegations. And the FBI could find no evidence that the AFC received Nazi funding. Yet Roosevelt continued violating their civil liberties by attempting to suppress their message of non-intervention.

Military Buildup

While the official U.S. policy remained neutrality, Roosevelt’s rhetoric edged closer and closer to military intervention. As early as 1937, Roosevelt declared that aggressor nations such as Germany and Italy should be “quarantined.” Many Americans accused Roosevelt of trying to lead the U.S. into an unnecessary war.

By 1939, concerned by the expansionism of Germany, Italy, and Japan, Roosevelt began requesting billions of dollars to build up the U.S. naval fleet and bolster national defense. When the German invasion of Poland prompted Britain and France to declare war, the U.S. officially declared neutrality. However, Roosevelt persuaded Congress to revise the neutrality laws so that the cash-and-carry provision covered war equipment along with non-war products. This clearly benefited Britain and France because they dominated Atlantic shipping. By the end of the year, the U.S. was selling war products to Britain.

Germany responded to the change in U.S. policy by declaring unrestricted submarine warfare on U.S. shipping. In June 1940, Roosevelt declared that “the whole of our sympathies lies with those nations that are giving their life blood in combat against these forces (i.e., Germany, Italy, and Japan).” The next year, U.S. forces occupied Greenland and Iceland, ostensibly to protect U.S. shipping from Nazi submarines. However, these countries gave the U.S. a better position to aid Britain in violation of both its own neutrality laws and international law.

Urgings from Britain

Britain desperately worked to undermine U.S. neutrality and get the U.S. into the war, especially after the Nazis conquered France in June 1940. Britain was nearly bankrupt and could no longer take advantage of the cash-and-carry provision. Moreover, the British were under relentless assault from the German Luftwaffe. From this point forward, Roosevelt worked hard to sway public opinion in favor of the British and against the Germans.

At Britain’s urging, Roosevelt got Congress to enact the first peacetime military draft in U.S. history. By the end of 1940, Roosevelt urged the U.S. to become the “great arsenal of democracy” against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan, despite the fact that the U.S. was not at war with them. This was Roosevelt’s first attempt to gauge public opinion concerning involvement, and to his dismay, most Americans still opposed entering the war.

In the fall of 1940, Roosevelt violated neutrality laws by loaning naval destroyers to Britain in exchange for leases on British military bases. The assistant secretary of state noted that Germany could have very well declared war on the U.S. for this. Roosevelt could have been impeached for effecting this agreement without congressional consent, which was unconstitutional. But instead Congress upheld Roosevelt’s decision by passing the Lend-Lease Act in 1941. This extended aid not only to Britain but also to China, and later the Soviet Union as they battled the Axis.

The “lend-lease” agreement violated U.S. and international neutrality laws, but Roosevelt went even further. In early 1941, British and U.S. officials began talks on how to best defeat the Axis Powers, even though the U.S. was not in the war. By the summer of 1941, the U.S. assets of the Axis Powers had been frozen, an embargo was imposed on the Axis, and the German and Italian consulates were closed. These were belligerent acts under international law.

Dealings with the Axis

In early 1941, Roosevelt ordered U.S. warships to report the movement of German ships. He also authorized naval patrols to alert British ships to the presence of German submarines, a clear violation of neutrality. In addition, Roosevelt lifted the “combat zone” designation of the Red Sea. This allowed him to bypass the neutrality laws and deliver goods to Egypt, where British troops were fighting the Germans.

In Asia, Roosevelt worked to stop Japan’s increasing military expansion. To appease the isolationists, Roosevelt did not respond militarily when Japan accidentally bombed U.S.S. Panay in China’s Yangtze River in 1937, even though many in the Roosevelt administration conceded that war was inevitable.

By 1940, Roosevelt began imposing embargoes against Japan on items such as oil, gasoline, iron, and steel. Since Japan had no oil resources of its own, it relied on imports to expand its empire. Cutting off imports greatly increased the probability that Japan would attack the U.S. But Roosevelt did not explain the implications of such embargoes to the public, which is why most Americans were so shocked when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The “Victory Program” Helps Lead to War

Roosevelt’s “Victory Program,” begun in July 1941, included accelerating the military draft, building war industries, and bolstering national defense in preparation for military conflict. In August, Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill drafted the Atlantic Charter. Despite supposed neutrality, the charter included a clause in which the U.S. agreed to join in “the destruction of Nazi tyranny.”

Meanwhile, the oil embargo on Japan was causing increased desperation. Japan could have accepted U.S. demands to cease expansion, but it chose a more militant route. Roosevelt refused to participate in negotiations, despite the U.S. ambassador to Japan’s claims that negotiations would have worked. The only other option was war, and unbeknownst to the public, Roosevelt administration officials believed that war was inevitable. And on December 7, 1941, the war came.

Historians and scholars have argued that Roosevelt’s actions were justified because many Americans who opposed the war were too short-sighted to see the true evil of the Axis Powers. But if a president is allowed to violate laws and lie to the public, what would stop a future president from doing the same for less honorable reasons? Roosevelt’s actions set a dangerous precedent under which presidents ever since have gradually seized more power and disclosed less information to the public. This precedent eventually led to U.S. involvement in conflicts such as Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and the current War on Terror.

January 21, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jan 21-27, 1863

Wednesday, January 21. In northern Virginia, General Ambrose Burnside’s Federal Army of the Potomac remained paralyzed by the driving winter rains that turned roads into impassable mud and slime. In Texas, two Federal blockaders were captured by Confederate steamers at Sabine Pass.

[image error]

Burnside’s “Mud March”

Confederate President Jefferson Davis dispatched General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Western Department, to General Braxton Bragg’s headquarters at Tullahoma, Tennessee to investigate criticism that Bragg had unnecessarily retreated from the Battle of Stone’s River. Davis was concerned that Bragg’s subordinates lacked confidence in their commander.

President Abraham Lincoln endorsed a letter from General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck to General Ulysses S. Grant explaining why Grant had been ordered to revoke his General Order No. 11. The controversial order had expelled all Jews from Grant’s military department. Halleck explained that Lincoln did not object to expelling “traitors and Jew peddlers,” but “as it in terms proscribed an entire religious class, some of whom are fighting in our ranks, the President deemed it necessary to revoke it.” The expulsion order was never enforced.

Lincoln officially cashiered General Fitz John Porter from the U.S. Army and forever disqualified him from holding any government office. This came after a January 10 court-martial convicted Porter of disobeying orders during the Battle of Second Bull Run the previous August. The ruling was reversed in 1879, and Porter was restored to the rank of colonel in 1886.

Thursday, January 22. In northern Virginia, Ambrose Burnside’s Federals were stalled in mud, unable to cross the Rappahannock and attack General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Trains and wagons were stuck, horses and mules were dying, and the Federals were demoralized.

Ulysses S. Grant assumed command of all Federal troops in Arkansas. Within this, President Lincoln ordered General John McClernand’s Army of the Mississippi to return from its unauthorized expedition to Fort Hindman and become a corps under Grant’s command. This eventually caused resentment between the two generals, though Lincoln asked McClernand “for my sake, & for the country’s sake, you give your whole attention to the better work.” Grant renewed efforts to cut a canal across “Swampy Toe” opposite Vicksburg that would move boats and men around the fortress city.

Friday, January 23. In northern Virginia, severe storms continued as Ambrose Burnside’s Federals pulled back to their winter quarters. The “mud march” ended in miserable failure. Many of Burnside’s subordinates criticized his leadership, but his harshest critic was Joseph Hooker, who called Burnside incompetent and the Lincoln administration feeble. Burnside responded by issuing General Order No. 8, charging Hooker with “unjust and unnecessary criticisms… endeavored to create distrust in the minds of officers… (including) reports and statements which were calculated to create incorrect impressions…” Burnside asked permission from President Lincoln to remove William B. Franklin, W.F. Smith, and others from the army, and to remove Hooker from the service entirely. Burnside also requested a personal meeting with the president.

Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Arkansas, and South Carolina. Lincoln began preparing orders to return General Benjamin Butler to New Orleans, replacing General Nathaniel Banks. The orders were never carried out.

Saturday, January 24. In northern Virginia, the Federal Army of the Potomac settled back into its gloomy winter quarters across from Fredericksburg while dissension among the ranks increased. President Lincoln conferred with General-in-Chief Halleck on the military situation and awaited Ambrose Burnside’s arrival. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Virginia.

Sunday, January 25. President Lincoln conferred with General Burnside this morning, who reiterated his demand to remove several generals from his command, otherwise he would resign. Later this morning, Lincoln resolved the dilemma by removing Generals Edwin V. Sumner and William B. Franklin from command. He also accepted Burnside’s resignation and replaced him with Joseph Hooker.

Burnside had reluctantly accepted command of the Army of the Potomac in the first place, and his ineptitude, first at Fredericksburg and then during the “mud march,” sealed his fate. The army was neither surprised nor disappointed by his removal. However, many were surprised that Hooker had been chosen to command, considering Hooker’s insubordinate comments about his superiors. Lincoln explained that he needed a fighter, and unlike Burnside, Hooker wanted the post.

Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Mississippi. In Arkansas, John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates reached Batesville. The organization of the first regiment of Federal Negro South Carolina soldiers was completed on the Carolina coast.

Monday, January 26. General Joseph Hooker assumed command of the Federal Army of the Potomac. In a letter, President Lincoln explained why he had been chosen to lead: “I have heard… of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.”

Skirmishing occurred in Florida, Arkansas, and Virginia. The Confederate commerce raider C.S.S. Alabama seized a Federal vessel off Santo Domingo (the present-day Dominican Republic).

Tuesday, January 27. In Georgia, Federal naval forces led by U.S.S. Montauk attacked Fort McAllister on the Ogeechee River south of Savannah. The squadron withdrew after several hours of bombardment. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia.

The proprietor of the Philadelphia Journal, A.D. Boileau, was arrested and brought to Washington to face charges for allegedly printing anti-Union material. President Davis complimented Georgia Governor Joseph Brown for reducing cotton cultivation and urging produce farming: “The possibility of a short supply of provisions presents the greatest danger to a successful prosecution of the war.”

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

January 19, 2013

Civil War Spotlight: The “Mud March”

In Virginia, Major General Ambrose Burnside’s Federal Army of the Potomac recuperated outside Fredericksburg following their terrible defeat in December. General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia remained entrenched between Burnside and the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Burnside met with President Abraham Lincoln to discuss a new plan of attack. Lincoln informed the general that several army subordinates had no confidence in him. Burnside offered to resign, but Lincoln refused because he had no practical replacement. Hoping to redeem himself, Burnside promised to strike “a great and mortal blow to the rebellion” by moving north along the Rappahannock River and attacking Lee’s left. Lincoln reluctantly approved the plan.

On January 19, the Army of the Potomac began mobilizing to cross the river and attack Lee’s Confederates once more. Icy rain began falling in torrents that night and continued for several days. Soon the entire Federal army became stuck in thick mud and slime. Ammunition and supply wagons were mired, horses and mules died of exhaustion, and trains were backed up for two miles.

With the army demoralized, Burnside canceled the offensive and ordered a withdrawal back to the original winter quarters outside Fredericksburg. The “mud march” was another Federal disaster. As complaints about Burnside increased, the general asked Lincoln to dismiss several subordinates. To Lincoln, the “mud march” indicated that Burnside’s usefulness had ended.

January 16, 2013

Corruption and the Transcontinental Railroad

Building a railroad across America was a remarkable engineering feat. However, the alliance between corporations and government that built the railroad set a precedent for the wasteful and corrupt mismanagement of taxpayer money that flourishes today.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law, which created two railroad corporations—the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific—that would build a railroad across the continent. Building the railroad was such a key goal of Lincoln and his fellow Republicans that they spent millions of taxpayer dollars on construction at a time when millions were already being spent each day fighting the Civil War.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act into law, which created two railroad corporations—the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific—that would build a railroad across the continent. Building the railroad was such a key goal of Lincoln and his fellow Republicans that they spent millions of taxpayer dollars on construction at a time when millions were already being spent each day fighting the Civil War.

The Competing Railroads

The Central Pacific (CP) began laying track eastward from Sacramento, California, and the Union Pacific (UP) was to lay track westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa. Eventually the two lines would meet, and this line would connect to the eastern rail networks to become the first transcontinental line.

The railroad companies were given taxpayer-funded government bonds and enormous tracts of land with which to build. The companies soon hired lobbyists to encourage the politicians in Washington to keep the subsidies flowing by exchanging stocks for votes. Since the government was funding construction, the companies were in no hurry to link their lines; in the first two and a half years of work, the UP line was still only 40 miles outside Omaha, Nebraska.

The UP especially benefited from government generosity. Its head, Thomas Durant, had bought land in Nebraska in the hopes that the government would select that site for construction. Those hopes became reality when Durant’s lawyer and chief lobbyist—Lincoln—was elected president in 1860. The Iowa delegation had helped to nominate Lincoln, so when the railway law passed in 1862, Lincoln returned the favor by selecting Council Bluffs as the UP’s eastern terminus.

Capitalizing on Government Generosity

Because the railroad companies were funded by taxpayers, there was less incentive to function efficiently or responsibly. The companies were paid based on the terrain on which they built, with rougher terrain being worth more. So company executives naturally selected roundabout routes on hills and through mountains, even though such routes were neither efficient nor safe. The cheapest supplies were also used, which virtually guaranteed shoddy workmanship and the need for future repairs.

Since work was funded by the government, executives often stole from their own companies for personal gain. Stocks were manipulated, as bosses bought struggling eastern rail companies, spread rumors that the transcontinental line would link to these companies, then sold them when their stock rose. This scheme raised an estimated $5 million.

Executives also spent large sums of money entertaining influential politicians instead of managing their businesses. Meanwhile, members of Congress argued over the route, as nearly every congressman wanted the line to go through his district or state. When the CP and UP came close to linking, they veered away from each other to continue the flow of government money. Congress finally demanded that they link at Promontory Point, Utah.

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of building the line concerned the fate of American Indians along the route. To stop Indian attacks on workers, executives hired hunters to slaughter buffalo, thus depriving the Indians of their primary food and clothing source. Indians responded by intensifying their attacks, and executives called on the government to help. U.S. troops were sent west, and the Plains Indian Wars that ensued led to the near genocide of the American Indian by the end of the 19th century.

Credit Mobilier

The widespread fraud and abuse surrounding the transcontinental line resulted in the greatest scandal of the 19th century. UP executives created a construction company called Credit Mobilier of America, then hired the company to build its portion of the rail line. Since the UP stockholders also owned Credit Mobilier stock, the executives essentially hired themselves to do the work.

The job cost taxpayers $72 million, even though the line only cost $53 million to build. When members of Congress began questioning this shady arrangement, Congressman Oakes Ames was assigned to distribute stock options and free railroad passes in exchange for silence. Those receiving the options included Vice President Schuyler Colfax and future President James A. Garfield.

The press exposed the scandal three years later, forcing Congress to investigate. Over 30 congressmen admitted to receiving stock options. Ames was censured for his role, but nobody else was punished. Technically no laws were broken since Congress conveniently passed no legislation outlawing such shady dealings. Nevertheless, Americans were enraged by this wasteful and unethical abuse of their tax dollars.

The scandal exposed a massive misuse of taxpayer funds by the corrupt alliance of government and business. However, Credit Mobilier was only one of many scandals and abuses perpetrated in the construction of this historic railroad.

Completion and Precedent

Celebrations took place throughout the country when the CP and UP linked at Promontory Point in 1869. Despite all the waste and fraud, this was one of the most remarkable engineering feats of the 19th century. In seven years, about 20,000 workers laid 1,775 miles of track, and coast-to-coast travel was reduced from six months to one week. Railroad executives had been given 23 million acres of land and $64 million in taxpayer money.

Despite the celebrations, the transcontinental railroad was not yet complete because its eastern terminus was at Omaha. Trains had to be ferried across to Missouri River until a bridge finally connected Omaha to Council Bluffs, Iowa in 1872.

Less than three years after the ceremony at Promontory Point, the UP declared bankruptcy due to vast inefficiency and waste. The CP ultimately went under as well. The shoddy workmanship on the line led to continuous repairs to bridges, viaducts, tunnels, rails, ties, and beds.

Following completion of the railroad and the revelations of Credit Mobilier, Congress passed drastic regulations on railroads that made it extremely difficult for private entrepreneurs to run an efficient rail company. Consequently, most government-subsidized railroads went bankrupt because they were bogged down by regulations and handicapped by the inefficiencies of taxpayer-funded “public works” projects.

Many historians have claimed that the great railroads of the late 19th and early 20th centuries could not have been built without government subsidies. However, the entire British railroad system was built with private funds, and the Great Northern Railroad under James J. Hill was a private transcontinental company that prospered when government-funded companies were going under.

As extraordinary as the transcontinental railroad was, it set an unfortunate precedent in which corporations turned to government to subsidize their projects at taxpayers’ expense. This ushered in the era of crony capitalism that still exists today in the form of bank and industry bailouts, and the diversion of taxpayer funds to favored industries. The most recent example is the Solyndra scandal, in which a solar panel company declared bankruptcy after receiving nearly $1 billion in taxpayer money.

Corruption, fraud, waste, and mismanagement still handicap projects undertaken by the government-corporate partnership, and this handicap will continue until the people elect politicians willing to break this dangerous alliance.

January 14, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jan 14-20, 1863

Wednesday, January 14. In Louisiana, Federal gunboats and troops attacked the Confederate gunboat Cotton and land fortifications at Bayou Teche. After a sharp fight, Cotton was burned the next morning. General Edmund Kirby Smith was given command of the Confederate Army of the Southwest.

Confederate General E. Kirby Smith

Thursday, January 15. In Arkansas, Federal troops burned Mound City, a center of guerrilla activities. The Confederate commerce raider Florida set sail from Mobile in a campaign against Federal shipping. Confederate President Jefferson Davis suggested to General Braxton Bragg, who had retreated from Murfreesboro to Tullahoma in Tennessee, “For the present all which seems practicable is to select a strong position and fortifying it to wait for attack.” President Abraham Lincoln demonstrated his interest in inventions and scientific developments by requesting tests for a concentrated horse food and a new gunpowder.

Friday, January 16. In Tennessee, a Federal expedition began from Fort Henry to Waverly. In Arkansas, the Federal gunboat Baron De Kalb seized guns and ammunition at Devall’s Bluff.

Saturday, January 17. President Lincoln signed a congressional resolution providing for the immediate payment of military personnel. Lincoln also requested currency reforms, as the war was costing $2.5 million per day by this year. The cost was financed by selling war bonds, borrowing over $1 billion from foreign countries, and issuing paper currency called greenbacks. These measures caused a massive increase in the cost of living through a new economic term called “inflation,” as well as enormous interest payments after the war that threatened U.S. economic stability.

Following the capture of Fort Hindman, General John A. McClernand’s Federal Army of the Mississippi began moving down the Mississippi River to Milliken’s Bend, north of Vicksburg. Skirmishing occurred at Newtown, Virginia, and a Federal expedition began from New Berne, North Carolina.

Sunday, January 18. Skirmishing occurred in the Cherokee Country of the Indian Territory and along the White River in Arkansas.

Monday, January 19. In northern Virginia, General Ambrose Burnside’s Federal Army of the Potomac began its second attempt to destroy General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg. Hoping to redeem himself after his disastrous defeat the previous month, Burnside promised to strike “a great and mortal blow to the rebellion” by moving north along the Rappahannock River and attacking Lee’s left. By evening, the Grand Divisions of Generals Joseph Hooker and William Franklin reached were prepared to cross the river.

President Lincoln responded to an address from workers of Manchester, Great Britain. He said he deplored the sufferings among mill workers in Europe caused by the cotton shortage, but it was the fault of “our disloyal citizens.” The Confederate government had unofficially banned the exportation of cotton, its greatest commodity, in the hopes that cotton-starved nations such as Britain and France would help the Confederacy gain independence so the cotton trade would resume. This became known as “King Cotton Diplomacy.”

Tuesday, January 20. In northern Virginia, Ambrose Burnside changed his plans for crossing the Rappahannock, and icy rain began falling in torrents. Burnside later said, “From that moment we felt that the winter campaign had ended.” During the night, guns and pontoons were dragged through the muddy roads as a winter storm ravaged the East.

In Missouri, John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates captured Patterson in continued raiding. General David Hunter resumed command of the Federal Department of the South.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

January 12, 2013

King Cotton Diplomacy

The Confederacy used cotton, its greatest commodity, as a tool for bargaining with foreign nations. When the war began, the Confederate government had unofficially banned the exportation of the commodity in the hopes that cotton-starved nations such as Great Britain and France would rush to help the Confederacy gain independence so the cotton trade would resume. This became known as “King Cotton Diplomacy.”

Some Confederate officials, such as Attorney General Judah Benjamin, opposed this self-imposed cotton embargo and urged an immediate resumption of trade to raise the revenue needed to repay loans and secure further credit to buy foreign war materiel.

“King Cotton Diplomacy” failed for several reasons. First, demand for southern cotton was diminished by surplus crops in Egypt and India. Thus foreign nations simply turned to those countries for their cotton. Moreover, most foreign entities had anticipated war in America and as such had stockpiled southern cotton in reserve.

Also, the self-imposed embargo deprived the Confederacy of much-needed revenue. Government bonds were sold and paper money was printed to help minimize the loss, but that only devalued the market and caused prices to soar. Thus, the policy greatly harmed southern citizens already burdened by the war.

Furthermore, the self-imposed embargo greatly helped the Federal naval blockade by giving it time to gather the strength needed to effectively shut down southern ports. When the war began, the Federals did not have enough warships to conduct a blockade, and the Confederacy could have easily established trade with other nations. When the Confederate government finally resumed the cotton trade this year, it was too late because the Federal blockade was now strong enough to stop cotton exports.

January 9, 2013

Why Alexander Hamilton Still Matters

Alexander Hamilton was one of the most influential figures in forming the United States. He was appointed by President George Washington to become the first Treasury secretary, largely because of his background in economics and his service in the War for Independence. But Hamilton sought to transform America into another England by centralizing power in the national government at the states’ expense. And politicians have been copying this approach ever since.

At the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton pushed to create a strong central government. He proposed that the president serve for life as a quasi-king, with powers to appoint state governors and veto federal and state laws. Hamilton only reluctantly endorsed the final Constitution because it was a slight improvement upon the decentralized Articles of Confederation.

Although he worked to persuade the states to support the new Constitution in The Federalist papers, Hamilton truly admired the British mercantilist system. This system featured excessive government spending that created massive debt, and high taxes that raised money to subsidize favored businesses in exchange for political favors. Believing that this was what made Great Britain a world power, Hamilton set out to create a similar system in America.

The basis of Hamilton’s economic policy was provided in three reports he issued to Congress. The proposals in these reports perverted the Constitution’s intent by trying to centralize power in the federal government. They also set a trend for economic policy and constitutional interpretation that most politicians still favor today.

Report on the Public Credit

Hamilton’s first report Congress offered two proposals. First, the federal government would assume all state and non-federal debts, then combine them with the national debt; this was called “assumption.” Removing financial obligations from the states would harm their credit and make them more dependent on the federal government in handling the economy. Southerners in Congress opposed this plan, not only because it weakened state power, but because most debt was in the northern states, and those in debt-free states felt no obligation to bail out less fiscally-prudent states.

Second, the federal government would repay the debt by selling government bonds. Most of the current national debt was in bonds issued to war veterans in lieu of pay. Paying this off by issuing more bonds would create a permanent cycle of debt that would finance future government operations. It would also entice creditors to ally themselves with the new government, thus forming a relationship between business and government that was strikingly similar to that in England.

Many, including Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Congressman James Madison, argued that the Constitution had no provision to allow such proposals as these. Hamilton countered that these were among the federal government’s “implied powers,” in which the ends (funding the government) justified the means (violating the Constitution). Ultimately, southerners agreed to support the Assumption Bill when northerners agreed to move the national capital from New York City to the South.

Hamilton’s notion of “implied powers” has been used by politicians to justify unconstitutional measures ever since. Disagreements over Hamilton’s plan led to the creation of political factions, the forerunners to political parties. In addition, the federal assumption of state debts set the trend of placing the federal government in control of the national economy, which continues today. It also led to the creation of Washington, DC, the future national capital.

Report on a National Bank

Hamilton’s second report offered two more proposals. First, a U.S. Mint would be created to print a national currency. At the time, state and local banks printed their own money, leading to various currencies with different exchange rates. Hamilton argued that the U.S. needed a uniform monetary system if it was going to survive and prosper.

Second, a national bank would be created to hold government revenue, meet the government payroll, circulate the new national currency, and provide steady credit to the federal government. The bank would be created by selling $10 million in stock, of which the U.S. would buy a share of $2 million. Since the U.S. did not have $2 million, Hamilton would arrange a U.S. loan to itself, which was essentially illegal. The other $8 million in shares would be bought by private investors. This was modeled after the Bank of England.

Southerners were suspicious of a central bank that could infringe on states’ rights by allowing private investors to gamble with taxpayer money (i.e., allowing bankers to feed at the public trough). Hamilton countered that the Constitution provided the federal government with the “necessary and proper” power to tax, coin money, and regulate interstate commerce, and under this, a national bank was a means to the end. After consulting with his cabinet, President Washington reluctantly signed the Excise Bill into law, and the Bank of the United States became the forerunner to today’s Federal Reserve System.

Hamilton’s argument that it is valid to use unconstitutional means (creating a mint and national bank) to achieve a constitutional end (coin money, collect taxes, etc.) set a vital trend. It helped ally government with private bankers and investors, creating the mercantilist system—also known as crony capitalism—that dominates the U.S. economy today.

Report on Manufactures

In Hamilton’s third report, he wrote, “The public purse must supply the deficiency of private resources.” To remedy this, he offered two proposals. First, tariffs (i.e., taxes) would be imposed on imported goods to make American products cheaper and more desirable. Second, revenue from the tariffs would be used to provide “bounties” (i.e., subsidies) to stimulate industry and make America competitive on a global scale.

Opponents argued that the Constitution only allowed the federal government to impose tariffs to raise revenue, not to protect American business. They also argued that subsidizing favored businesses had no constitutional basis. Others noted that such a system was suspiciously similar to the British system that so many Americans had just fought to get rid of.

Hamilton countered that such a program would benefit the “general welfare” of the nation, as provided in the Constitution. Once again, the ends (national stability) would be justified by the means (unconstitutional taxing and spending).

Congress rejected this report, but it reemerged in later years and was eventually adopted by the Whig, Republican, and Democratic parties in various forms. Hamilton’s economic policy set the trend for subsidizing businesses, which is known as “pork barrel spending” today.

Hamilton’s Policies Remain

Many of America’s founders, most notably Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, stringently opposed Alexander Hamilton’s economic policies. In fact, Jefferson ultimately resigned from George Washington’s cabinet in protest of Washington’s support for Hamilton. This helped forge the first political factions in the U.S.: the Republicans led by Jefferson and the Federalists led by Washington and Hamilton.

Hamilton recognized the coming of the industrial revolution. He also saw great potential in the alliance of industry and capitalism to transform America into a world power. However, Hamilton tried to speed up the alliance through government intervention. This only led to mercantilism, which is the antithesis of the free market capitalism that many Americans had sought after freeing themselves from England.

The sovereignty of states and individuals was weakened by Hamilton’s quest to centralize power. This contradicted most founders who drafted the Constitution. Hamilton’s liberal constitutional interpretations have reduced the states’ ability to resist the growing federal authority. They have also produced philosophical descendants such as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Richard M. Nixon, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama.

Hamilton’s ideas of accumulating national debt, creating a national bank, and subsidizing favored businesses have been fully enacted in one form or another. There is a vast national debt, banking is centrally planned through the Federal Reserve System, and many businesses and industries are routinely subsidized with taxpayer money. Over 200 years after his death, Alexander Hamilton’s vision for America is now a reality. And in many ways, Hamilton’s ideas betrayed the principles that Americans fought for in the War for Independence.

January 7, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jan 7-13, 1863

Wednesday, January 7. Federal General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck wrote to General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Army of the Potomac, emphasizing “our first object was, not Richmond, but the defeat or scattering of Lee’s army.” Halleck strongly backed Burnside’s plan to attack across the Rappahannock.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis wrote to General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, asking Lee to call on the Federal commanders to “prevent the savage atrocities which are threatened.” If the Federals did not comply, Lee should inform them that “measures will be taken by retaliation to repress the indulgence of such brutal passion.”

Confederate General John S. Marmaduke

In Missouri, General John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates captured Ozark and advanced on Springfield. A group of 450 women and children left Washington, DC for Richmond and the Confederacy with permission from the Federal government. The Richmond Enquirer called the Emancipation Proclamation “the most startling political crime, the most stupid political blunder, yet known in American history… Southern people have now only to choose between victory and death.”

Thursday, January 8. President Abraham Lincoln wrote to troubled Ambrose Burnside, “I do not yet see how I could profit by changing the command of the A.P. (Army of the Potomac) & if I did, I should not wish to do it by accepting the resignation of your commission.”

Defending the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln wrote to General John A. McClernand that “it must stand… As to the States not included in it, of course they can have their rights in the Union as of old.” President Davis wrote to General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Western Theater, “To hold the Mississippi is vital.”

In Missouri, John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates were repulsed by the Federal garrison at Springfield. In Washington, the U.S. Senate confirmed President Lincoln’s appointment of John P. Usher of Indiana as Interior secretary. Usher replaced Caleb Smith, who resigned due to poor health. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Virginia, and Arkansas.

Friday, January 9. In Tennessee, General William S. Rosecrans reorganized the Federal Army of the Cumberland into three corps commanded by George H. Thomas, Alexander McD. McCook, and Thomas L. Crittenden.

In Missouri, the Federal garrison at Hartville surrendered to John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates. Boat crews from U.S.S. Ethan Allen destroyed salt works near St. Joseph’s, Florida.

Saturday, January 10. John A. McClernand’s Federals closed in on Arkansas Post, or Fort Hindman, about 50 miles up the Arkansas River from its junction with the Mississippi. McClernand drove in on the outer earthworks, and naval bombardment stopped Confederate artillery. Land units were poised to attack the besieged Confederates under General Thomas J. Churchill.

President Lincoln wrote to General Samuel Curtis in St. Louis about his concern with the slave problem in Missouri. A Federal military court-martial dismissed General Fitz John Porter from the U.S. Army for failing to obey orders during the Battle of Second Bull Run the previous August. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Arkansas, and Federal warships bombarded Galveston, Texas.

Sunday, January 11. After a two-day naval bombardment, John A. McClernand launched a Federal ground attack on Fort Hindman on the Arkansas River. The overwhelmed Confederate defenders quickly surrendered. The Federals captured nearly 5,000 prisoners, 17 cannon, 46,000 rounds of small arms ammunition, and seven battle flags. While this was a Federal success, the fort itself held little strategic significance. Moreover, it diverted troops from the primary campaign against Vicksburg.

The prominent Confederate blockade runner, C.S.S. Alabama, sank U.S.S. Hatteras off Galveston, Texas. Hatteras had been on blockade duty when she was attacked by the stronger Alabama. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Missouri. In Missouri, John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates withdrew from Hartville. On the Mississippi River north of Memphis, Confederates surprised, captured, and burned U.S.S. Grampus No. 2.

Monday, January 12. The third session of the 1st Confederate Congress assembled in Richmond and received a message from President Davis. The message criticized the Emancipation Proclamation because it could lead to the wholesale murder of blacks and slaveholders, thus revealing the “true nature of the designs” of the Republican Party. Davis requested legislation amending the draft laws and providing relief for citizens in war-torn regions of the South.

Skirmishing occurred in Arkansas. General John E. Wool assumed command of the Federal Department of the East.

Tuesday, January 13. The U.S. War Department officially authorized the recruitment of blacks for the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, to be commanded by Colonel Thomas W. Higginson.

In Arkansas, a Federal expedition began from Helena. In Tennessee, a Federal reconnaissance began from Nashville to the Harpeth and Cumberland Rivers, and another Federal reconnaissance began from Murfreesboro. U.S.S. Columbia ran aground off North Carolina; the vessel was captured and burned by Confederates.

At the Harpeth Shoals on the Cumberland River in Tennessee, U.S. gunboat Slidell surrendered to General Joseph Wheeler’s Confederates. Three transports with wounded troops were also seized; Wheeler put the wounded all on one transport and allowed it to proceed, then burned the other two.

January 6, 2013

Why the Twenties Roared

The 1920s became known as the “Roaring Twenties” partly because government did what it should do today: mind its own business!

When World War I ended in 1918, the countries involved began the painful task of converting their wartime economies to peacetime. While most of these countries, particularly those in Europe, converted through increased government regulation, the U.S. took the opposite approach and reduced government constraints. This resulted in the greatest prosperity boom in modern history.

When World War I ended in 1918, the countries involved began the painful task of converting their wartime economies to peacetime. While most of these countries, particularly those in Europe, converted through increased government regulation, the U.S. took the opposite approach and reduced government constraints. This resulted in the greatest prosperity boom in modern history.

Limited Government Intervention

By war’s end, most Americans were tired of government intrusions on individual liberty that had been taking place for a generation. Many were also discouraged by the Treaty of Versailles, which suggested that perhaps the war had been fought in vain. As a result, voters in 1920 elected politicians that pledged to return to the founders’ policy of non-intervention, both at home and abroad.

Warren Harding became president in 1921 on a promise to return America to “normalcy.” At the time, the U.S. was languishing in an economic depression as Americans struggled to convert to a peacetime footing, and the U.S. struggled to convert from a farm-based economy to an economy based on industry. Harding, noting the unpopular economic interventions of his predecessor, Woodrow Wilson, determined to let things correct themselves without substantial government help.

In reviewing Wilson’s economic record, members of Harding’s administration recognized that government was actually harming the economy through excessive taxing and spending. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon determined that the top income tax rate of 73 percent encouraged taxpayers to hide their wealth, which decreased government revenue. It also resulted in less production, innovation, and investment, which meant less jobs. Thus, Mellon recommended drastic tax cuts that proved phenomenally successful.

Within five years, the top income tax rate had been cut to 25 percent, and both government and business revenues soared. This, along with reduced government spending, cut the national debt from $24 billion to $18 billion in that same time span. With increased revenues came increased investments that created millions of new jobs. By 1926, the national unemployment rate fell to an all-time low of one percent.

The rollback of government interference in the economy stemmed from the belief of both Harding and his successor, Calvin Coolidge, that government should be a referee, not a player, in the relationship between producers and consumers. This was consistent with the nation’s founding principles, and it helped generate the largest burst of manufacturing and innovation in American history.

Technological Achievements

Advances in technology and managerial methods, along with the perfection of mass production techniques, led to the unprecedented innovation and invention of breakthrough products and devices that changed society forever.

The assembly line in auto manufacturing sparked a 225 percent increase in auto production in the 1920s. This sparked competition, as Ford was challenged as the industry’s leader by General Motors, Packard, and other manufacturers. Increased competition provided more choices to consumers at lower prices.

Increased auto production led to increased road and highway construction, which created jobs. More cars also meant more jobs in industries that helped build and maintain cars, such as steel, glass, lumber, rubber, paint, and oil. With more people owning cars came more mobility, which enhanced both tourism and job searches.

Housing construction set records in the 1920s, as more jobs meant that more people could afford to buy their own homes. More jobs also meant more people could buy new appliances such as vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, ovens, and washing machines. Many appliance companies began employing assembly line techniques, making these products more accessible and affordable than ever before.

Radio became the primary form of entertainment; by 1929, radio sales were 1,400 percent higher than they had been in 1920, and nearly every home had a radio. The motion picture industry flourished as well, with silent movies soon giving way to Technicolor and the first major talking picture: The Jazz Singer in 1927. Sports became a national craze for the first time, with athletes such as Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, and Red Grange becoming legends.

The aviation industry was boosted by Charles Lindbergh’s historic nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. This led to an increase in passenger air travel. The telephone became an indispensible household item for the first time, and advances in science led to immunizations for diphtheria and breakthroughs in nutrition that helped improve the public’s health.

Other Factors Leading to Prosperity

Increased wealth led to increased speculation in the stock market, as Wall Street became the financial capital of the world in the 1920s. By 1928, 28 percent of Americans owned stock, up from 15 percent in 1900. The increased speculation led to more investment in various industries, which created even more jobs.

The federal government banned alcohol in the 1920s, but that only drove the industry underground. Soon, gangsters turned bootlegging into big business. “Speakeasies” sprang up everywhere, people mixed their own “bathtub” gin, and booze became a $3.5 billion-per-year racket. Prohibition ended in 1933 as one of the worst Progressive failures in history.

American entrepreneurs held an advantage over their European counterparts in that they had a domestic market unscathed by the devastating war. The U.S. also possessed vast materials and resources, which were employed to their maximum efficiency as more corporations invested in marketing, research, and development to enhance production.

The Beginning of the End

Many historians claim that the government’s laissez-faire (i.e., “hands-off”) approach to the economy led to unbridled greed that was corrected by the inevitable “hangover” of the Great Depression. However, government never had a truly “hands-off” policy in the 1920s. High tariffs harmed foreign trade, farm bailouts led to agricultural overproduction, and credit was irresponsibly extended by the Federal Reserve. These policies were enforced throughout the decade, and they helped lead to the downturn.

When Herbert Hoover became president in 1929, he intensified the counterproductive policies by offering more farm bailouts and enacting the highest tariff in U.S. history. These, combined with a Federal Reserve that suddenly decided to stop extending credit, sparked a stock market crash. Hoover (and later Franklin D. Roosevelt) sought to remedy the crash with even more counterproductive policies, which only pushed the economy out of a recession and into the Great Depression.

Politicians of today could learn from the vast improvement of living standards and prosperity in the 1920s that government works best when it stays within its constitutional boundaries and allows the free market to determine its own value. The freedom of individuals to produce, innovate, and prosper allowed the 1920s to roar. Massive government intervention in the private sector during the 1930s silenced that roar.

January 4, 2013

Civil War Spotlight: The Battle of Stone’s River

A battle that had begun near Murfreesboro in central Tennessee on December 31, 1862 resumed in January after a brief respite. During that time, Major General William S. Rosecrans had withdrawn his Federal Army of the Cumberland to stronger positions. He ordered fresh supplies and ammunition, then awaited an attack from General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee.

A portion of Bragg’s army under Major General John C. Breckinridge attacked and captured a small hill northeast of Stone’s River, but they were repulsed with heavy losses by Federal artillery and a countercharge. By nightfall, both armies fell back. Rain turned the battlefield into a quagmire, and after a limited Federal attack on January 3, Bragg withdrew toward Tullahoma, Tennessee.

The Federals suffered 12,906 killed, wounded, or missing, and the Confederates lost 11,739. Rosecrans was surprised by Bragg’s withdrawal and did not pursue. This prompted Bragg to claim a tactical victory. However, it soon became apparent that this was a significant Confederate defeat. The Battle of Stone’s River secured Kentucky and Tennessee for the Federals. It also boosted the morale of pro-Union eastern Tennesseans and demoralized Confederate sympathizers in central Tennessee and Kentucky.

President Lincoln wired Rosecrans, “God bless you and all with you… I can never forget… that you gave us a hard-earned victory, which, if there had been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.” Rosecrans soon began planning a Federal advance on the vital railroad city of Chattanooga.

For the Confederates, many saw this defeat as a missed opportunity to destroy the northern war effort after the Federals had been so soundly beaten at Fredericksburg the previous month. Bragg was criticized for withdrawing unnecessarily. A Confederate soldier wrote, “I am sick and tired of this war, and, I can see no prospects of having peace for a long time to come… the Yankees cant whip us and we can never whip them, and I see no prospect of peace unless the Yankees themselves rebell and throw down their arms, and refuse to fight any longer.”