Mary Cronk Farrell's Blog, page 17

May 16, 2014

Would you risk your life for a better high school? Barbara Johns did.

You’ve heard about Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on the bus, but does the name Barbara Johns mean anything to you?

Long before the Montgomery Bus Boycott 16-year-old Barbara took a courageous stand for civil rights when she led fellow students to boycott their segregated high school in the town of Farmville, Virginia.

Here’s a photo of the high school for white students in Farmville in 1951, it had had plenty of classrooms and a gymnasium, cafeteria, infirmary, and other resources.

Photo Courtesy of the National Archives

Photo Courtesy of the National Archives

Courtesy National Archives Barbara’s younger sister Joan Johns Cobb describes the situation at the school for black students.

Courtesy National Archives Barbara’s younger sister Joan Johns Cobb describes the situation at the school for black students.

The school we went to was overcrowded. Consequently, the county decided to build three tarpaper shacks for us to hold classes in. A tarpaper shack looks like a dilapidated black building, which is similar to a chicken coop on a farm…. In winter the school was very cold. And a lot of times we had to put on our jackets. Now, the students that sat closest to the wood stove were very warm and the ones who sat farthest away were very cold…. When it rained, we would get water through the ceiling. So there were lots of pails sitting around the classroom. And sometimes we had to raise our umbrellas to keep the water off our heads. It was a very difficult setting for trying to learn.

The author of the new book THE GIRL FROM THE TAR PAPER SCHOOL, Teri Kanefield says Barbara Johns risked her life, “but she wasn't afraid. She truly believed she was on the right side” the morning she stood up at a school assembly, asked the teachers to leave the auditorium and then asked her fellow students to walk out in protest.

The author of the new book THE GIRL FROM THE TAR PAPER SCHOOL, Teri Kanefield says Barbara Johns risked her life, “but she wasn't afraid. She truly believed she was on the right side” the morning she stood up at a school assembly, asked the teachers to leave the auditorium and then asked her fellow students to walk out in protest.

Barbara was a quiet, studious girl. But the morning of April 23, 1951, she took off her shoe and pounded it on the podium to get her point across. "Don't be afraid, just follow us out," she said.

Courtesy Joan Johns Cobbs That day, when the curtains opened it was my sister on stage rather than the principal. I was totally shocked, said Joan Johns Cobb. I remember sitting in my seat and trying to go as low in the seat as I possibly could because I was so shocked and so upset. I actually was frightened because I knew that what she was doing was going to have severe consequences.

Courtesy Joan Johns Cobbs That day, when the curtains opened it was my sister on stage rather than the principal. I was totally shocked, said Joan Johns Cobb. I remember sitting in my seat and trying to go as low in the seat as I possibly could because I was so shocked and so upset. I actually was frightened because I knew that what she was doing was going to have severe consequences.

Because at the time, you still read of lynchings…. And so therefore, everyone was afraid that he or she would be lynched. Even, at the time, for talking back to a white person or in the case of the black men, speaking to a white woman. So we all lived with that type of fear. It was real. It was scary.

Students remained out of school and after two weeks, NAACP lawyers joined the effort, filing a petition in court to desegregate the Prince Edward County schools. In reaction someone burned a cross in the schoolyard, a black minister supporting the strike received death threats and a homemade bomb died out on his doorstep.

Barbara received several threats and her parents sent her out of town to live with an uncle and finish high school.

The legal challenge to segregated schools failed, but three years later, Barbara was one of the plaintiffs in Brown vs Board of Education which outlawed school segregation throughout the land.

Teri Kanefield says Barbara Johns is a reminder that every single day, history is being made. “It has taken almost a half century for her [Barbara] to be widely recognized as a true American hero. This makes me believe there are Barbara Johnses among us now, but we are not recognizing them as visionaries and heroes.”

One of the author’s favorite aspects of the story is that young people convinced the adults to take action.

Tomorrow is the 60th Anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling on Brown Vs Board of Education. Today the Christian Science Monitor reports that since then, any gains in racial integration in American schools have mostly been reversed.

Long before the Montgomery Bus Boycott 16-year-old Barbara took a courageous stand for civil rights when she led fellow students to boycott their segregated high school in the town of Farmville, Virginia.

Here’s a photo of the high school for white students in Farmville in 1951, it had had plenty of classrooms and a gymnasium, cafeteria, infirmary, and other resources.

Photo Courtesy of the National Archives

Photo Courtesy of the National Archives

Courtesy National Archives Barbara’s younger sister Joan Johns Cobb describes the situation at the school for black students.

Courtesy National Archives Barbara’s younger sister Joan Johns Cobb describes the situation at the school for black students.The school we went to was overcrowded. Consequently, the county decided to build three tarpaper shacks for us to hold classes in. A tarpaper shack looks like a dilapidated black building, which is similar to a chicken coop on a farm…. In winter the school was very cold. And a lot of times we had to put on our jackets. Now, the students that sat closest to the wood stove were very warm and the ones who sat farthest away were very cold…. When it rained, we would get water through the ceiling. So there were lots of pails sitting around the classroom. And sometimes we had to raise our umbrellas to keep the water off our heads. It was a very difficult setting for trying to learn.

The author of the new book THE GIRL FROM THE TAR PAPER SCHOOL, Teri Kanefield says Barbara Johns risked her life, “but she wasn't afraid. She truly believed she was on the right side” the morning she stood up at a school assembly, asked the teachers to leave the auditorium and then asked her fellow students to walk out in protest.

The author of the new book THE GIRL FROM THE TAR PAPER SCHOOL, Teri Kanefield says Barbara Johns risked her life, “but she wasn't afraid. She truly believed she was on the right side” the morning she stood up at a school assembly, asked the teachers to leave the auditorium and then asked her fellow students to walk out in protest.Barbara was a quiet, studious girl. But the morning of April 23, 1951, she took off her shoe and pounded it on the podium to get her point across. "Don't be afraid, just follow us out," she said.

Courtesy Joan Johns Cobbs That day, when the curtains opened it was my sister on stage rather than the principal. I was totally shocked, said Joan Johns Cobb. I remember sitting in my seat and trying to go as low in the seat as I possibly could because I was so shocked and so upset. I actually was frightened because I knew that what she was doing was going to have severe consequences.

Courtesy Joan Johns Cobbs That day, when the curtains opened it was my sister on stage rather than the principal. I was totally shocked, said Joan Johns Cobb. I remember sitting in my seat and trying to go as low in the seat as I possibly could because I was so shocked and so upset. I actually was frightened because I knew that what she was doing was going to have severe consequences.Because at the time, you still read of lynchings…. And so therefore, everyone was afraid that he or she would be lynched. Even, at the time, for talking back to a white person or in the case of the black men, speaking to a white woman. So we all lived with that type of fear. It was real. It was scary.

Students remained out of school and after two weeks, NAACP lawyers joined the effort, filing a petition in court to desegregate the Prince Edward County schools. In reaction someone burned a cross in the schoolyard, a black minister supporting the strike received death threats and a homemade bomb died out on his doorstep.

Barbara received several threats and her parents sent her out of town to live with an uncle and finish high school.

The legal challenge to segregated schools failed, but three years later, Barbara was one of the plaintiffs in Brown vs Board of Education which outlawed school segregation throughout the land.

Teri Kanefield says Barbara Johns is a reminder that every single day, history is being made. “It has taken almost a half century for her [Barbara] to be widely recognized as a true American hero. This makes me believe there are Barbara Johnses among us now, but we are not recognizing them as visionaries and heroes.”

One of the author’s favorite aspects of the story is that young people convinced the adults to take action.

Tomorrow is the 60th Anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling on Brown Vs Board of Education. Today the Christian Science Monitor reports that since then, any gains in racial integration in American schools have mostly been reversed.

Published on May 16, 2014 08:23

May 1, 2014

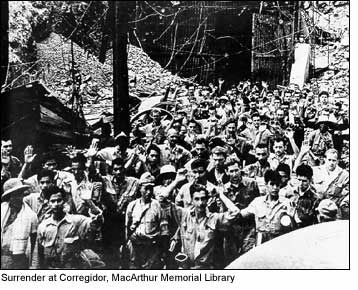

The Last Desperate Days on Corregidor

"Situation here is fast becoming desperate," General Jonathon Wainwright cabled General Douglas MacArthur May 3, 1942.

"Situation here is fast becoming desperate," General Jonathon Wainwright cabled General Douglas MacArthur May 3, 1942.The next night the Navy risked a daring mission, as Submarine Spearfish glided past a Japanese minesweeper and destroyer, to surface. A small boat motored out to meet it carrying 25-passengers, including eleven nurses. Read more about Spearfish rescue...

What would turn out to be the last U.S. mail shipment to leave Corregidor was also taken aboard, including some hastily scrawled letters to family. Army Nurse Hattie Brantley didn't bother. "I couldn't write a letter to my family. What was I going to say?"

The Spearfish dived 200 feet below the sea, stealing away toward Australia, leaving fifty-four army nurses and twenty-six Filipina nurses behind.

In the next 24-hours over May 4 and 5, the Japanese hammered Corregidor with some 16,000 shells, then as the first landing force took the beaches, nurses on duty in Corregidor's underground hospital destroyed records, keeping their gas masks handy.

Army Nurses Alice Zwicker confided in her diary, "Even all the rumors of what the Japanese may do to all of us and especially the women mean little or nothing to me at the present. Just end this awful destruction and find help for these patients who need the barest essentials so badly."

Another nurse ventured into the main tunnel just before the surrender. Dirty, hungry and exhausted men filled the passageway. "Some asked for water, some for food, and the pity was that we had very little of either. Some were swearing, some staring into space. She hurried back to the nurses' lateral, where her off-duty colleagues huddled, starved for food and for news.�����The next wave of Japanese rolled tanks onto Corregidor's beaches and Wainwright imagined the wholesale slaughter that would befall his men, and "...I thought of the havoc that even one tank could wreak if it nosed into the tunnel, where lay our helpless wounded and their brave nurses."

He sent men out with white flags at 10A.M.

Most nurses heard the news over the tunnel radio. Surrender would come at noon May 6. "Now our facial expressions were stony, and we avoided letting our eyes meet," said Army Nurse Denny Williams. "Not only our own hopeless fear, but collective fear, with it's power to panic, passed from person to person like a current, lurching and jolting on-off on-off, but always more intense until I had visions of our soldiers fighting until all were dead outside and the enemy came inside, screaming and brandishing swords and bayonets. I wondered if I would die and how I would die. I hoped to be quiet and brave."

Most nurses heard the news over the tunnel radio. Surrender would come at noon May 6. "Now our facial expressions were stony, and we avoided letting our eyes meet," said Army Nurse Denny Williams. "Not only our own hopeless fear, but collective fear, with it's power to panic, passed from person to person like a current, lurching and jolting on-off on-off, but always more intense until I had visions of our soldiers fighting until all were dead outside and the enemy came inside, screaming and brandishing swords and bayonets. I wondered if I would die and how I would die. I hoped to be quiet and brave."  The women had arrived in the Philippines unprepared for war, but learned quickly when driven to the limits of endurance nursing wounded and dying American soldiers. Now they would face the horrors of prison camp for three years before General MacArthur would reclaim the Philippines and liberate them.

The women had arrived in the Philippines unprepared for war, but learned quickly when driven to the limits of endurance nursing wounded and dying American soldiers. Now they would face the horrors of prison camp for three years before General MacArthur would reclaim the Philippines and liberate them.

Published on May 01, 2014 22:12

April 24, 2014

That phone call you never want to get...

GABE ~ June 1996-April 2008 It was nearing midnight six years ago today when I got the phone call. You know the one. The one you never, ever want to receive. I’d been out celebrating with a friend whose new book had just came out, and had just settled into bed, ready to drift off to sleep.

GABE ~ June 1996-April 2008 It was nearing midnight six years ago today when I got the phone call. You know the one. The one you never, ever want to receive. I’d been out celebrating with a friend whose new book had just came out, and had just settled into bed, ready to drift off to sleep.“Gabe’s not doing well,” she said.

The tremble in her voice told me this was the worst kind of news. Gabe was in the hospital, but he’d been in before, and I’d never thought for one second that his life was in danger.

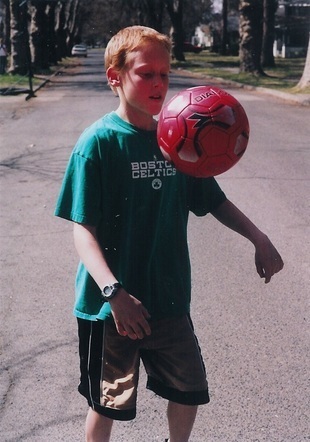

Gabe was the eleven-year-old son of a very close friend. The family lived directly across the street from our house and I’d known Gabe since he was born.

When I got off the phone my heart was beating so hard and fast, it seemed it would bust right out of my chest. My thoughts were completely incoherent. I knew I should get dressed and go to the hospital. But for a few moments I couldn’t even think how to put on a pair of pants.

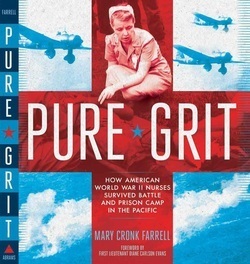

I dedicated my book PURE GRIT to Gabe because of the courage he demonstrated living with epilepsy. For several years, his seizures were controlled by medication.

But they grew worse and occasionally, the medication didn't work. Gabe loved basketball, and he would take to the floor with his team, even though he knew he might have a seizure on the court at any time.

But they grew worse and occasionally, the medication didn't work. Gabe loved basketball, and he would take to the floor with his team, even though he knew he might have a seizure on the court at any time.He didn't have grand mal seizures, but he would lose consciousness momentarily, freeze when all the other players ran down the court. His arm would stiffen out to the side. It might seem a small thing, but it's a huge risk to a child with epilepsy. It would have been easier to not to play, not to take the chance you might look strange in front of your friends and a whole gym full of strangers.

Over time, stronger and stronger meds helped less and less. Doctors urged Gabe's parents to consider surgery to excise a part of his brain where the seizures originated. Brain surgery is always high risk. Anything might go wrong, but even a successful surgery could compromise Gabe's motor skills. He was a natural athlete and loved soccer, as well as basketball.

Gabe's courage was often invisible. And it's hard to put into words. You would have had to live with him day in and day out to understand the courage it took for him to go to school when the meds made him drowsy, for him dribble a ball down the court when he'd had five seizures his last game. To see his strength, you would have had to be there when he went in to the hospital to have his brain mapped with electrodes.

You would have had to see Gabe's face as he was wheeled away from his mom and dad and into surgery where the doctors would cut into his brain to understand that kind of courage. I mostly heard about it from his mom.

Every night, she had the task of asking him how many seizures he had that day and recording the number, if it hadn't been too many to count.

Every night, she had the task of asking him how many seizures he had that day and recording the number, if it hadn't been too many to count.Gabe had a hilarious sense of humor. He had bright blue eyes and a sweet, sometimes goofy smile. He used to shoot baskets at the hoop on the street for hours. He loved to watch LaBron James play ball.

Everyone was so excited the night he came home from that surgery, head shaved with a row of stitches across his scalp. Smiling.

Everyone was so excited the night he came home from that surgery, head shaved with a row of stitches across his scalp. Smiling. It was a year later when it became clear the surgery hadn't ended the seizures. One day Gabe had so many, he was hospitalized and doctors put him into a coma to stop them. It was a tragic fluke that Gabe suffered an allergic reaction to the Propofol they used to knock him out. His doctors had never seen it happen before.

I doubt there's a parent alive who has not wondered how they would go on living if their child died. I never want to find out, but I have witnessed it now.

After Gabe died, I learned the profound journey it can be to closely accompany a mother through such a loss. To witness such indescribable pain moment to moment, hour to hour, day to day, and year to year as it gives way ever so gradually to healing, is to witness a miracle of courage.

And so I dedicated PURE GRIT, not only to Gabe, but to his mother Cheryl. It's a small way to honor them and give thanks for how they have inspired me and enriched my life.

Published on April 24, 2014 21:23

April 17, 2014

You won’t believe how a losing 6th grade history fair project out-gunned the Navy

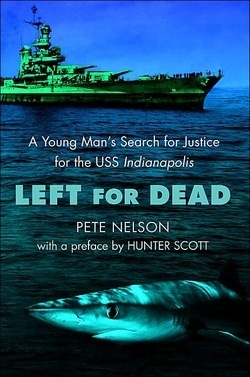

The story of the USS Indianapolis was not pretty. Sunk by the Japanese at the close of WWII, only a quarter of her crew survived. Her captain was court-martialed and killed himself, possibly to escape the shame.

Then in 1997, a sixth grader, Hunter Scott, interviewed survivors of the disaster for the school history fair. He thought they were heroes and that their captain got a bum deal. His project won the school fair, the country fair and then lost the state fair to a rock collection.

But the boy believed in his project and continued his research, as well as his efforts to tell the true story of USS Indianapolis.

The historical relevance of the ship was assured because of its secret mission, transporting the atomic bomb to the Mariana Islands in prep for the bombing of Hiroshima. As it turns out, that is but a footnote in the nearly unbelievable tale of this ship and men who sailed aboard her.

I learned about it in the book

Left for Dead: A Young Man’s Search for Justice for the USS Indianapolis

by Pete Nelson. The book combines the story of the survivors of the U.S. Navy's worst loss of life on a single ship with the story of Hunter Scott crusade to bring them the honor they deserved.

I learned about it in the book

Left for Dead: A Young Man’s Search for Justice for the USS Indianapolis

by Pete Nelson. The book combines the story of the survivors of the U.S. Navy's worst loss of life on a single ship with the story of Hunter Scott crusade to bring them the honor they deserved.

After delivering the bomb, the Indianapolis set a leisurely course to the Philippines for some gunnery practice. The Indy was a cruiser, without the heavy armor of a battleship. At this point in the war, most of the fighting had moved to the far eastern Pacific closer to Japan, so the ship sailed without an escort. Though Japanese submarines had been sited earlier on the route, that information was classified and Captain Charles B. McVay wasn’t told.

Captain Charles B. McVay It late July, a mere 12-degrees from the equator, as the ship sailed through the muggy heat, air-ducts, water-tight doors and hatches were opened to cool the lower decks. Still, many sailors carried their blankets topside and found a space to catch the breeze and get some sleep.

Captain Charles B. McVay It late July, a mere 12-degrees from the equator, as the ship sailed through the muggy heat, air-ducts, water-tight doors and hatches were opened to cool the lower decks. Still, many sailors carried their blankets topside and found a space to catch the breeze and get some sleep.

Shortly before midnight on July 29, a Japanese submarine surfaced, and the captain, looking through his binoculars saw a black dot on the horizon. He thought it was fate, for as he watched, the moon come out of the clouds right behind the ship. Silhouetted on the vast dark ocean, the Indianapolis sailed straight toward him. He gave the order to dive, and then to fire.

At 12:02 the first torpedo hit, ripping off the front starboard corner of the Indianapolis and igniting a tank of highly volatile aviation fuel. Seconds later, two more explosions rocked the ship. Bulkheads collapsed, the ship took on water and the engines drove the Indy down. It took only twelve minutes to sink.

About 300 men died outright or went down with the ship; 880 were thrown into the sea. They huddled together in groups and tried to stay afloat in the oil-slick, shark-infested waters. Some were burned or otherwise injured; many had no life-jackets. The worst-off got to rest in life rafts, safe from the sharks. But there had only been time to cut loose a few of the rafts and there were too few survival provisions for the number of men in the water.

One of the radio operators encouraged those around him, telling how he had sent out the SOS and their location. They must simply hang on until rescuers arrived.

Nelson goes into detail about the horrors the men faced as they waited. The burned and bleeding, those with broken limbs and dazed from concussions were the first to die. Daylight brought sunburn and thirst and no rescue. The second day brought dehydration, hunger and nasty disputes. The third day brought hallucinations, and loss of the will to live. Every day the sharks came. They swam in circles around the groups of men. Without warning a man would scream, then disappear into the deep. Men went out of their minds.

The United States Navy did not even know the Indianapolis was missing. It would be more than 50-years before the Navy discovered that the SOS message had been received by four different people. Hunter Scott discovered that in each case, it had been ignored.

On the fourth day after the ship sank, survivors were sighted by chance, and planes and boats headed to the area to save them. The last of the 317 men alive was picked out of the ocean on the fifth day.

Survivors aboard the USS Bassett. Rescued after four days in the ocean.

Survivors aboard the USS Bassett. Rescued after four days in the ocean.  Survivors arriving on Guam after rescue. The Navy needed a scapegoat for this disaster and court-martialed the captain for not ordering a zig-zag course to avoid enemy torpedoes. The surviving men knew their captain was not to blame, and tried in vain for years to clear his name.

Survivors arriving on Guam after rescue. The Navy needed a scapegoat for this disaster and court-martialed the captain for not ordering a zig-zag course to avoid enemy torpedoes. The surviving men knew their captain was not to blame, and tried in vain for years to clear his name.

Then in 1997, 11-year-old Hunter Scott heard Indianapolis disaster mentioned in the movie Jaws and decided to interview survivors for his history fair project. That set him on a course of friendship with the men and finally the exoneration of Captain McVay.

I recommend this book because it's an important story that honors the survivors of the USS Indianapolis.There are recommend this book for two things the author does very well. One is the way he describes the science of how the human body reacts when deprived of drinking water while suspended in salt water. The second is his explanation of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as it was suffered by the survivors of the Indianapolis, and how, when in 1960, the men began to gather and talk about what had happened they began to heal. That healing was also helped in 2001 when, after Hunter Scott took their case to Congress, the crew of the Indianapolis were finally awarded a Navy Unit Citation.

Then in 1997, a sixth grader, Hunter Scott, interviewed survivors of the disaster for the school history fair. He thought they were heroes and that their captain got a bum deal. His project won the school fair, the country fair and then lost the state fair to a rock collection.

But the boy believed in his project and continued his research, as well as his efforts to tell the true story of USS Indianapolis.

The historical relevance of the ship was assured because of its secret mission, transporting the atomic bomb to the Mariana Islands in prep for the bombing of Hiroshima. As it turns out, that is but a footnote in the nearly unbelievable tale of this ship and men who sailed aboard her.

I learned about it in the book

Left for Dead: A Young Man’s Search for Justice for the USS Indianapolis

by Pete Nelson. The book combines the story of the survivors of the U.S. Navy's worst loss of life on a single ship with the story of Hunter Scott crusade to bring them the honor they deserved.

I learned about it in the book

Left for Dead: A Young Man’s Search for Justice for the USS Indianapolis

by Pete Nelson. The book combines the story of the survivors of the U.S. Navy's worst loss of life on a single ship with the story of Hunter Scott crusade to bring them the honor they deserved.After delivering the bomb, the Indianapolis set a leisurely course to the Philippines for some gunnery practice. The Indy was a cruiser, without the heavy armor of a battleship. At this point in the war, most of the fighting had moved to the far eastern Pacific closer to Japan, so the ship sailed without an escort. Though Japanese submarines had been sited earlier on the route, that information was classified and Captain Charles B. McVay wasn’t told.

Captain Charles B. McVay It late July, a mere 12-degrees from the equator, as the ship sailed through the muggy heat, air-ducts, water-tight doors and hatches were opened to cool the lower decks. Still, many sailors carried their blankets topside and found a space to catch the breeze and get some sleep.

Captain Charles B. McVay It late July, a mere 12-degrees from the equator, as the ship sailed through the muggy heat, air-ducts, water-tight doors and hatches were opened to cool the lower decks. Still, many sailors carried their blankets topside and found a space to catch the breeze and get some sleep.Shortly before midnight on July 29, a Japanese submarine surfaced, and the captain, looking through his binoculars saw a black dot on the horizon. He thought it was fate, for as he watched, the moon come out of the clouds right behind the ship. Silhouetted on the vast dark ocean, the Indianapolis sailed straight toward him. He gave the order to dive, and then to fire.

At 12:02 the first torpedo hit, ripping off the front starboard corner of the Indianapolis and igniting a tank of highly volatile aviation fuel. Seconds later, two more explosions rocked the ship. Bulkheads collapsed, the ship took on water and the engines drove the Indy down. It took only twelve minutes to sink.

About 300 men died outright or went down with the ship; 880 were thrown into the sea. They huddled together in groups and tried to stay afloat in the oil-slick, shark-infested waters. Some were burned or otherwise injured; many had no life-jackets. The worst-off got to rest in life rafts, safe from the sharks. But there had only been time to cut loose a few of the rafts and there were too few survival provisions for the number of men in the water.

One of the radio operators encouraged those around him, telling how he had sent out the SOS and their location. They must simply hang on until rescuers arrived.

Nelson goes into detail about the horrors the men faced as they waited. The burned and bleeding, those with broken limbs and dazed from concussions were the first to die. Daylight brought sunburn and thirst and no rescue. The second day brought dehydration, hunger and nasty disputes. The third day brought hallucinations, and loss of the will to live. Every day the sharks came. They swam in circles around the groups of men. Without warning a man would scream, then disappear into the deep. Men went out of their minds.

The United States Navy did not even know the Indianapolis was missing. It would be more than 50-years before the Navy discovered that the SOS message had been received by four different people. Hunter Scott discovered that in each case, it had been ignored.

On the fourth day after the ship sank, survivors were sighted by chance, and planes and boats headed to the area to save them. The last of the 317 men alive was picked out of the ocean on the fifth day.

Survivors aboard the USS Bassett. Rescued after four days in the ocean.

Survivors aboard the USS Bassett. Rescued after four days in the ocean.  Survivors arriving on Guam after rescue. The Navy needed a scapegoat for this disaster and court-martialed the captain for not ordering a zig-zag course to avoid enemy torpedoes. The surviving men knew their captain was not to blame, and tried in vain for years to clear his name.

Survivors arriving on Guam after rescue. The Navy needed a scapegoat for this disaster and court-martialed the captain for not ordering a zig-zag course to avoid enemy torpedoes. The surviving men knew their captain was not to blame, and tried in vain for years to clear his name.Then in 1997, 11-year-old Hunter Scott heard Indianapolis disaster mentioned in the movie Jaws and decided to interview survivors for his history fair project. That set him on a course of friendship with the men and finally the exoneration of Captain McVay.

I recommend this book because it's an important story that honors the survivors of the USS Indianapolis.There are recommend this book for two things the author does very well. One is the way he describes the science of how the human body reacts when deprived of drinking water while suspended in salt water. The second is his explanation of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as it was suffered by the survivors of the Indianapolis, and how, when in 1960, the men began to gather and talk about what had happened they began to heal. That healing was also helped in 2001 when, after Hunter Scott took their case to Congress, the crew of the Indianapolis were finally awarded a Navy Unit Citation.

Published on April 17, 2014 19:58

April 3, 2014

Sit still: Turn Your Fear into Wisdom

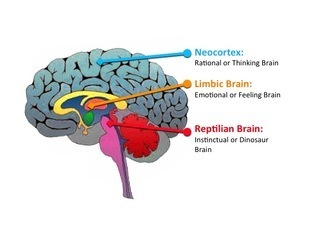

Graphic from dangerandplay.com I click open my novel to start revising and my heartbeat goes-- fight-or-flight, fight-or-flight, fight-o-flight!

Graphic from dangerandplay.com I click open my novel to start revising and my heartbeat goes-- fight-or-flight, fight-or-flight, fight-o-flight!I jump up and go to the kitchen to microwave my cup off coffee. Even though it hasn’t cooled.

In the moment of facing the page, I am like a mouse bolting from the swoop of a hawk. My amygdala (reptilian brain) fires a message to my sympathetic nervous system telling it that my body is in acute danger. This message is so commanding, I jump up and leave the room.

I wrote about this fear a few months ago when I asked the question: What would you do, if you weren’t afraid. I’m exploring it more deeply today and asking: Why does part of my brain think revising a novel is a threat to my life? And what the heck am I going to do about it?

First, I’m going to remind myself it’s not me. Fear happens to everyone.

Sometimes I think the difference between what we

want and what we're afraid of is about the width of

an eyelash. ― Jay McInerney

What I want is risk. What I fear is failing. What I

want is fresh air, currents, and mountains. What I’m

afraid of is heights, drowning, and change. – Lakin Easterling

Fear of failure is part of the human condition, so I accept it. But acceptance isn’t standing on the doorstep, neither in nor out. Stepping into fear is crossing the threshold between the conscious and unconscious mind.

When I feel my heart going fight or flight- fight or flight- fight or flight, acceptance means taking a deep breath and sitting still. Not scampering to the kitchen and not forcing myself to get started on that revision no matter what it takes.

Sitting still, breathing deep, feeling fear. Feeling my rapid heart beat, feeling my quickened breath, feeling the nerve endings in my skin waking up. Letting the fear rise. Listening to what it’s trying to tell me. This what’s called getting to know yourself.

In decades past, this was woo-woo, some silly sh%t therapist’s would tell you to do. In this decade it’s imperative.

It’s imperative because if we don’t listen to the fear and learn, we will act on it. Everybody knows we humans don’t make good decisions with our amygdala.

Graphic from http://www.bewellassociates.com We need to act under the power of our prefrontal cortex deeply engaged with our heart.

Graphic from http://www.bewellassociates.com We need to act under the power of our prefrontal cortex deeply engaged with our heart.Sitting still and getting to know our fear gives our frontal lobe time to overrule our flight or flight, reptilian brain. Don’t worry, it will still work if you’re about to be hit by a car.

When we get familiar with our fear, we begin to realize that most of it is a lie. We’re afraid of things that might happen. Afraid of things we imagine. Afraid of things we can do absolutely nothing about.

That’s when our heart opens. Sitting still with an open heart, using our prefrontal cortex our actions will be wise.

When I feel my heartbeat speed up, and my breath quicken, I don’t say to myself, Mary, don’t be silly, revising a novel will not kill you. Rather, I see it as an opportunity to learn something about myself and to open my heart. I take it as an opportunity to practice acting from a place of wisdom.

Make sense? A bunch of hoo-rah? Let me know what you think.

Published on April 03, 2014 22:25

March 27, 2014

World War II Fly-Girls Denied Recognition for 70-Years

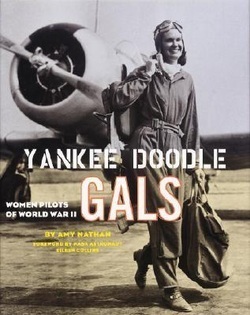

Elizabeth L. Gardner in a B-26 Marauder Like the WWII POW nurses I wrote about in PURE GRIT, the nearly two-thousand Women's Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) did not receive formal recognition for their courageous wartime service while they were alive. It took nearly 70-years and an act of Congress to get them a medal and formal thanks from the U.S. government.

Elizabeth L. Gardner in a B-26 Marauder Like the WWII POW nurses I wrote about in PURE GRIT, the nearly two-thousand Women's Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) did not receive formal recognition for their courageous wartime service while they were alive. It took nearly 70-years and an act of Congress to get them a medal and formal thanks from the U.S. government.In 1942 when America's pilots were desperately needed in combat zones, there were not enough men to cover the bases at home. Up stepped 25-thousand young women pilots, eager to take to the skies and serve their country. Less than 2000 were accepted.

"Here I was, a girl of 22, given a million-dollar airplane and told, "Go fly!" One said.

They were not trained for combat, but flew fighter planes, bombers and every other kind of aircraft the U.S. Army had in World War II. The daring young WASPs not only transported cargo and flew planes from the factories to training bases and points of embarkation. They towed targets for live anti-aircraft artillery practice and simulated strafing missions.

The WASPs' story is told in the newly re-issued YANKEE DOODLE GALS, by Amy Nathan. She explains: Some were teenagers, right out of high school or just starting college. Others were teachers, librarians, flight instructors, or offices workers. They stopped what they were doing for the chance to fly fantastic planes and help their country win the war. These 1,102 women weren't allowed to fly in combat, but for two glorious years they put their lives on the line every day flying important, and often risky, stateside missions. They flew well and proved that a woman's place could very well be inside a military cockpit.

The WASPs' story is told in the newly re-issued YANKEE DOODLE GALS, by Amy Nathan. She explains: Some were teenagers, right out of high school or just starting college. Others were teachers, librarians, flight instructors, or offices workers. They stopped what they were doing for the chance to fly fantastic planes and help their country win the war. These 1,102 women weren't allowed to fly in combat, but for two glorious years they put their lives on the line every day flying important, and often risky, stateside missions. They flew well and proved that a woman's place could very well be inside a military cockpit.In 1944 the war was going better for the U.S. and the Army decided it didn't need the women anymore and disbanded the program. Though the women flew dangerous missions for two years and 38 of the pilots died in accidents, they were never considered official members of the military. All records of their service were classified and sealed for 35-years. Little remembered of the women pilots' contribution to the war effort.

Finally in 2009, President Barack Obama and the U.S. Congress awarded the WASPs the Congressional Gold Medal. Three of the roughly 300 surviving pilots were there for the honor.

During the ceremony President Obama said, "The Women Airforce Service Pilots courageously answered their country's call in a time of need while blazing a trail for the brave women who have given and continue to give so much in service to this nation since. Every American should be grateful for their service, and I am honored to sign this bill to finally give them some of the hard-earned recognition they deserve."

Published on March 27, 2014 22:44

March 20, 2014

Believing in Contradictions Builds Resilience

As many of you know it's been a rough week saying good-bye to my brother-in-law Javier. When you lose someone you love, you wonder how the world can just go on like it does. The rain still falls, cars go by, people haggle over the last piece of bacon.

As many of you know it's been a rough week saying good-bye to my brother-in-law Javier. When you lose someone you love, you wonder how the world can just go on like it does. The rain still falls, cars go by, people haggle over the last piece of bacon. The gift of grieving is the compassion that comes with the realization that it's not my grief. It's our grief. In every small town and big city, someone's heart is breaking over the loss of a loved one. In every language spoken on earth people cry out in sorrow.

Grief is born of love. Can we let our hearts be tender to its touch?

Everyday life is full of contradictions, situations where opposites are true at the same time. Practicing our ability to hold opposing truths builds resilience and lies at the core of a full and healthy life.

Everyday life is full of contradictions, situations where opposites are true at the same time. Practicing our ability to hold opposing truths builds resilience and lies at the core of a full and healthy life.After Javier's accident and traumatic brain injury, my sister Virginia lived with contradiction for seven-and-a-half weeks. She held hope and belief that her husband would recover, and she knew it was possible he wouldn't survive.

Virginia cried in anguish, prayed with faith and she also laughed with joy. The staff at the hospital loved her. (As do we all) They continually spoke of her courage, her warmth, and her commitment to Javier. In between helping with Javier's therapy, she crocheted scarves for other patients! She attuned to joy in the midst of deep sorrow.

The joy of one last time on Daddy's 'dozer Virginia also juggled the contradictions innate between the needs of her husband and the needs of her young children. I love to see her smile and talk about her children. She told me a story about her five-year-old who said, "When Daddy comes home, I'm going to teach him his numbers and colors. Ten plus ten is twenty. Daddy's brain doesn't know that. But mine does." Virginia's practice of holding both joy and sorrow has strengthened her for the days of grief to come.

The joy of one last time on Daddy's 'dozer Virginia also juggled the contradictions innate between the needs of her husband and the needs of her young children. I love to see her smile and talk about her children. She told me a story about her five-year-old who said, "When Daddy comes home, I'm going to teach him his numbers and colors. Ten plus ten is twenty. Daddy's brain doesn't know that. But mine does." Virginia's practice of holding both joy and sorrow has strengthened her for the days of grief to come.This ability to hold and feel the opposites of joy and sorrow is critical to resilience. To cling only to sorrow, even though sorrow is true, leads to depression and/or bitterness. To cling solely to joy and not acknowledge the depths of pain and loss leads to numbness.

Most days, we will not deal with the extremes that Virginia faced. On the periphery of her story, I have practiced being present to her and to my own grief, while at the same time celebrating the launch of PURE GRIT and my joy in work well done.

U.S. Army Nurses at 126th General Hospital, Leyte, P.I., February 14, 1945. L to R, Helen Cassini, Anne Wurtz, Alice Zwicker, Letha McHale, Kay Acorn, Rita Palmer.

U.S. Army Nurses at 126th General Hospital, Leyte, P.I., February 14, 1945. L to R, Helen Cassini, Anne Wurtz, Alice Zwicker, Letha McHale, Kay Acorn, Rita Palmer. Grasping such contradictions helped the American WWII nurses survive combat and prison camp. In the midst of danger, fear and death, cracking jokes was one way the women stayed centered. For instance, when nurses couldn't bring themselves to eat due to anxiety during the air raids, one joked that if hit, their chances of survival would be better on an empty stomach.

After nearly three years in prison camp, the nurses continued to find humor in their situation to help keep their spirits up. Despite the hardships they suffered, the women grasped any excuse to celebrate.

Army Nurses Rita Palmer said later, "The birthdays and anniversaries of the members of each one's family far away in the United States or some country were duly feted with a special tablecloth and a cake.” They continued to celebrate when they no longer had ingredients to make a cake.

In late 1944, as many as five people were dying each day of starvation related ailments in Santo Tomas Internment Camp. The nurses were as sick as their patients.

Army Nurse Frances Nash was so weak, her legs swollen with beriberi that she could hardly walk to the hospital. She wrote in her diary, “We had stood more than I had ever thought the human body and mind could endure.”

She also wrote, “There was nothing beautiful in our lives except the sunsets and the moonlight.” Frances saw beauty in the midst of unimaginable suffering.

If we open ourselves to what is true moment by moment, we will experience contradiction. Embracing the contradictions builds resilience and invites the fullness of life to flow through us.

I'd love to know, what's your experience with these difficult contradictions in life and how we give them their due?

Published on March 20, 2014 17:32

March 14, 2014

Courage on the Face of a Third-Grader

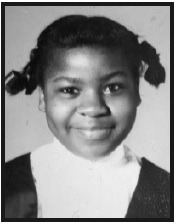

Audrey Faye Hendricks On Thursday morning, May 2, 1963, nine-year-old Audrey Faye Hendricks woke up with freedom on her mind. But, before she could be free, there was something important she had to do. "I want to go to jail," Audrey had told her mother.

Audrey Faye Hendricks On Thursday morning, May 2, 1963, nine-year-old Audrey Faye Hendricks woke up with freedom on her mind. But, before she could be free, there was something important she had to do. "I want to go to jail," Audrey had told her mother. Since Mr. and Mrs. Hendricks thought that was a good idea, they helped her get ready. Her father had even bought her a new game she'd been eyeing. Audrey imagined that it would entertain her if she got bored during her week on a cell block.

That morning, her mother took her to Center Street Elementary so she could tell her third-grade teacher why she'd be absent. Mrs. Wills cried. Audrey knew she was proud of her.

She also hugged all four grandparents goodbye. One of her grandmothers assured her, "You'll be fine."

Then Audrey's parents drove her to the church to get arrested.

That's the first page of WE'VE GOT A JOB: THE 1963 BIRMINGHAM CHILDREN'S MARCH, by Cynthia Levinson. Hooked? I was.

Cynthia graciously agreed to share something of what she learned about courage in the process of writing the book. Welcome, Cynthia.

Inevitably, a child asks me during a school visit, “So, would you do it?” I can tell by the group’s eager expressions that they want me to shout, “Absolutely!” They know they would do it.

Inevitably, a child asks me during a school visit, “So, would you do it?” I can tell by the group’s eager expressions that they want me to shout, “Absolutely!” They know they would do it. Invariably, however, I have to answer, “I wish I could say, ‘Yes.’ But I’m too cowardly.” Their new expressions tell me they’re disappointed. After all, why would their school invite an author who’s a wimp, especially when the story she’s just told them focuses on thousands of courageous children?

As a result, I’ve been tempted to alter my response. However, not only must I be honest but also I’ve begun to realize that, paradoxically, their disappointment is part of why I’m there.

When Mary Cronk Farrell asked me to write about how the subjects of my book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March, affected me, I knew the topic would be complex. Through the experiences of four specific young people, the book tells the story of how 3000 to 4000 black school children desegregated Birmingham, Alabama—the city that Dr. King considered the most violently racist in the country. It was certainly the most thoroughly segregated, with laws and customs decreeing that “Negro and white people are not to play together,” that a seven-foot wall must separate blacks and whites in restaurants, that separate ambulances should carry sick people to separate hospitals.

Author Cynthia Levinson Some black ministers and others tried for years to desegregate the town. But a racist police commissioner, named “Bull” Connor, who ignored bombs tossed at the homes and churches of civil rights activists, defeated them. Instead, children took the lead that May. They protested, picketed, sat-in at lunch counters, and, above all, marched. Even when the commissioner attacked them with snarling German shepherds and powerful water canons, the children held hands and kept marching. They also sang, prayed, were arrested en masse, spent days and nights in packed jails—and did it all peacefully. Two months later, the commissioner was defeated, and Birmingham rescinded its onerous and despicable segregation codes.

Author Cynthia Levinson Some black ministers and others tried for years to desegregate the town. But a racist police commissioner, named “Bull” Connor, who ignored bombs tossed at the homes and churches of civil rights activists, defeated them. Instead, children took the lead that May. They protested, picketed, sat-in at lunch counters, and, above all, marched. Even when the commissioner attacked them with snarling German shepherds and powerful water canons, the children held hands and kept marching. They also sang, prayed, were arrested en masse, spent days and nights in packed jails—and did it all peacefully. Two months later, the commissioner was defeated, and Birmingham rescinded its onerous and despicable segregation codes.So, when I tell school children today about the brave youngsters in Birmingham, they want to know if I would march, too. Would I sing and pray? Would I face dogs, hoses, and jail? The reason that I know, unfortunately, that I would not is that I did not.

In May 1963, I was an eighteen-year-old high school senior in Columbus, Ohio. In fairness, not a single white person joined the black children during their protests in Birmingham so it’s not completely surprising that I didn’t fly down there. (Some white clergymen and the folk singer Joan Baez did, however.) Nevertheless, to the extent that I paid attention to the news, I was bewildered by what was happening down there. Worse, I hardly paid attention at all. In fact, although I knew about the dogs and the hoses, I didn’t know that it was children who took responsibility for desegregating their city until decades later. Furthermore, although later I did participate in a few protests about political issues I cared about, I chose tame ones where no one was going to get hurt.

Because we know how events in the past have turned out, history in hindsight looks inevitable. Young people today could believe that the children of Birmingham weren’t in any real danger. Beforehand, however, Dr. King was so worried that someone might get hurt or killed that he opposed their actions. Sharing my own embarrassing past with them, I think, makes the threats more real. These were truly dangerous times.

Courage, I hope they learn, does not entail ignoring the dangers but, rather, paying attention to them—and then making a decision about whether or not to proceed. Courage, I’ve learned, is not casual. Courage requires a cause. And, courage draws strength from cooperation.

Thank you, Cynthia, for sharing your thoughts here. I'm moved by your honesty. We can all stand to look more closely at what's happening in the life around us and how we respond. I know your book will inspire many of us to do that. Click here for more on WE'VE GOT A JOB.

Published on March 14, 2014 08:39

March 7, 2014

Blogs Feature WWII Women POWs for Women's History Month

Dorothy Scholl graduated from nursing school in 1936, Photo courtesy of Carolyn Armold Torrence A huge thank you to bloggers featuring PURE GRIT to celebrate Women's History Month!

Dorothy Scholl graduated from nursing school in 1936, Photo courtesy of Carolyn Armold Torrence A huge thank you to bloggers featuring PURE GRIT to celebrate Women's History Month!Seventy-nine American WWII nurses survived combat and three years as POWs of the Japanese, but the story is perhaps best told through the eyes of a single nurse.

Dorothy Scholl was born a hundred years ago, the same year five-thousand suffragists marched to the White House amid much ridicule and abuse by an antagonistic mob. She grew up far from Pennsylvania Avenue, the ninth child of ten on a farm in Missouri. But she had the independent spirit of a 20th Century woman, and two of Dorothy’s older sisters helped send her to nursing school. Read more...

Over at her blog READ LIKE A WRITER, a Teaching Blog, Author Christine Kohler offers a look at how the stories of the World War II POW nurses were almost lost forever.

Over at her blog READ LIKE A WRITER, a Teaching Blog, Author Christine Kohler offers a look at how the stories of the World War II POW nurses were almost lost forever. In 1945, when the women arrived home after their three years as POW’s in the Philippines, their superiors had them sign statements agreeing not to speak of the atrocities they had seen.

“They treated it as if it was a stigma,” said Lieutenant Colonel Hattie R. Brantley.

A good number of the seventy-eight POW nurses had died before there was any effort to preserve their stories. Read more...

And check out Christine's novel NO SURRENDER SOLIDER, a story encompassing the experiences of a WWII soldier, a Vietnam soldier and the boy that links the two.

Published on March 07, 2014 07:31

February 25, 2014

Pub day for PURE GRIT

Buy now! So excited to announce pub day for PURE GRIT. At times it seemed this day would never come. I started research the summer of 2007. The book proposal sold to Abrams in August 2010. February 25, 2013 the book is on store shelves and earns a terrific review from Book Kvetch! Could not have done it without the help of so many of you. Thank you from the bottom of my heart!

Buy now! So excited to announce pub day for PURE GRIT. At times it seemed this day would never come. I started research the summer of 2007. The book proposal sold to Abrams in August 2010. February 25, 2013 the book is on store shelves and earns a terrific review from Book Kvetch! Could not have done it without the help of so many of you. Thank you from the bottom of my heart!"Pure Grit by Mary Cronk Farrell is a highly worthwhile read and a first-rate history for YA readers on the experiences of combat nurses serving valiantly in the Philippines during World War II....[It] might prompt interesting classroom inquiry and discussion of issues relevant to women in military service." Read full review here.

Published on February 25, 2014 08:12