Lisa M. Lilly's Blog, page 18

September 1, 2015

Live to Work or Work to Live: Thoughts on Work/Life Balance

The other day on a podcast, entrepreneur and author Joanna Penn said something like you only worry about work/life balance when you dislike what you do. This caught my ear. My feelings about how work fits in my life, or how it "should" fit, have changed during the last six months, partly because I've shifted professionally so that most of my work time relates to my thriller writing. Even so, I'm not sure I completely agree with Joanna's comment.

During the 14+ years when the majority of my work time (the majority of all my time, for that matter) was spent practicing law, I strived to keep a sharp divide between what I did to earn a living and the rest of life. That seemed vital because I worked so many hours, first at a large law firm and then running my own law practice. I rarely worked at law projects at home and rarely handled anything personal from my office. I also tried to designate certain times of the week--Saturday evening, all day Sunday--whenever I could as non-work time. My thriller and horror writing, though also work, was my great love, so I counted it on the "life" side of the balance.

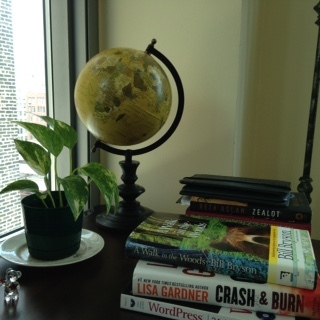

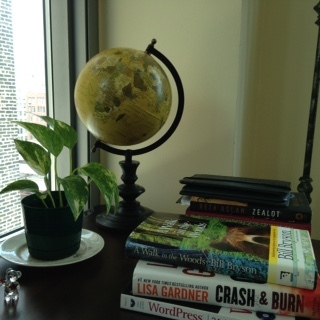

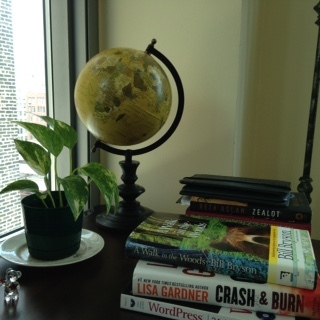

My view as I write this post.Now that I spend most of my professional life writing, and a smaller amount practicing law and teaching, work/life balance isn't a big focus for me, yet I'm happier. I sometimes choose to research or write legal motions and briefs Saturday and Sunday mornings so I can send my final product off to a client or file it in a court early, leaving the rest of the week for revising the third thriller in my Awakening series. Likewise, I might grade the papers my law students write while taking Amtrak to visit family, despite that it's officially vacation, because it helps pass the long train ride. Or I'll sit out on my deck and dictate parts of a blog post into my phone while watching a beautiful sunset, which is how I began this entry.

My view as I write this post.Now that I spend most of my professional life writing, and a smaller amount practicing law and teaching, work/life balance isn't a big focus for me, yet I'm happier. I sometimes choose to research or write legal motions and briefs Saturday and Sunday mornings so I can send my final product off to a client or file it in a court early, leaving the rest of the week for revising the third thriller in my Awakening series. Likewise, I might grade the papers my law students write while taking Amtrak to visit family, despite that it's officially vacation, because it helps pass the long train ride. Or I'll sit out on my deck and dictate parts of a blog post into my phone while watching a beautiful sunset, which is how I began this entry.

At first I struggled against this migration of work into evenings and weekends--those times I'd tried so hard, often without success, to keep sacred when I labored primarily at law. But being too rigid led to me feeling both busier and as if I weren't getting as much done, as I always felt I ought to be doing something else. Paying bills during 9-5 when I'm most sharp and productive seemed like a waste, as did going to the grocery store during evenings or weekends when everyone else is there. When I felt freer to handle tasks when I'd be most productive at them or enjoy them more regardless of the time or place, I discovered I found it easier to relax during downtime, plus I had more of it. Letting myself open my laptop on a Saturday morning to rewrite a scene that had sifted through my mind during the night gave me more than one uninterrupted hour to read a novel during the week. Immersing myself in reading that way is something I loved from childhood on but hadn't done regularly since before I'd started law school. From then on, reading for pleasure happened only in 10-20 minute increments unless I was on vacation.

------------------------------------------------------------------Join Lisa M. Lilly's M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) Reader Group and receive Ninevah, a short horror story published exclusively for subscribers, free. Your email address will never be shared or sold.-------------------------------------------------------------------Now I wonder if, while I was practicing law full time, I might have been happier had I allowed myself the same flexibility. I liked my work, and I loved running my own business. But I got depressed, feeling like the only person in the whole world working when I stayed at my office every night until 7 p.m. At the big law firm where I'd practiced, seven was a normal time to leave work, but on my own most of the people where I shared offices left by 5 or 6. And on weekends, it was just me and the security guards. I might have felt happier doing routine administrative tasks at home with a glass of wine and John Fogerty playing on the stereo.

One of the things I do identify with that Joanna Penn said is that because she loves writing and everything connected to it, her leisure time and social interactions all often relate to her work, and she enjoys that. Authors need to read, and that's a great love of mine. I've also made very close friends at writing conferences and more recently through writing communities on line. We've become sounding boards for one another for our careers and for other parts of life. Plus we have fun. I recently had a great time eating good food and drinking wine at Lady Gregory in Chicago with my friend Patty, who runs Path to Essential Health. Yet we were having a business meeting about a creativity workshop we're putting together.

At the same time, I remember when I started my law firm I was also delighted at the many ways business and social came together. At the large firm, the hours of legal work required to meet guidelines left little time for any type of social life--business related or not. On my own, I was thrilled that I could eat lunch often with friends, attend bar association events, and host get togethers at my firm. That a side effect often was sharing good business advice or connecting one another with potential clients or vendors was icing on the cake. Three or four years later, though, when my practice had grown almost beyond me, I felt burnt out and tired. I still loved seeing my friends, but the hours in the office felt less rewarding, and I began to resent the lack of time away.

It's tempting to believe that'll never happen with my writing, and with the business side of writing, because I love it more. And that's probably true in part. But the author of The E-Myth Revisted, a book about entrepreneurs with small businesses, talks about the dangers of growth without a plan. The author gives examples of small business owners who survive the all important first five years (during which most small business fail) only to confront a challenge they never expected: too much success, resulting in working too much for too long and no longer loving the business. I recognized myself right away and realized that within a year of opening my doors I ought to have hired a full time legal assistant rather than doing so much myself with office support only on a project basis.

I plan to learn from that experience, so much as I love writing and everything connected with it, I'll make a a little nod to work/life balance more often than I feel the need to. Also thanks to Joanna's podcast, I've started scheduling my tasks for the following work day the night before. It helps me get more done and, as important, I schedule in breaks and I know when I'm finished for the day. And I'm keeping an eye on what additional aspects of my writing business and law practice I will outsource if I hit a point where I feel all I do is work.

What about you? Does whether you love your work affect your need for work/life balance? What tips can you offer on enjoying your life inside and outside of work?

---------------

Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. A short film of the title story of her collection The Tower Formerly Known as Sears and Two Other Tales of Urban Horror was recently produced under the title Willis Tower.

During the 14+ years when the majority of my work time (the majority of all my time, for that matter) was spent practicing law, I strived to keep a sharp divide between what I did to earn a living and the rest of life. That seemed vital because I worked so many hours, first at a large law firm and then running my own law practice. I rarely worked at law projects at home and rarely handled anything personal from my office. I also tried to designate certain times of the week--Saturday evening, all day Sunday--whenever I could as non-work time. My thriller and horror writing, though also work, was my great love, so I counted it on the "life" side of the balance.

My view as I write this post.Now that I spend most of my professional life writing, and a smaller amount practicing law and teaching, work/life balance isn't a big focus for me, yet I'm happier. I sometimes choose to research or write legal motions and briefs Saturday and Sunday mornings so I can send my final product off to a client or file it in a court early, leaving the rest of the week for revising the third thriller in my Awakening series. Likewise, I might grade the papers my law students write while taking Amtrak to visit family, despite that it's officially vacation, because it helps pass the long train ride. Or I'll sit out on my deck and dictate parts of a blog post into my phone while watching a beautiful sunset, which is how I began this entry.

My view as I write this post.Now that I spend most of my professional life writing, and a smaller amount practicing law and teaching, work/life balance isn't a big focus for me, yet I'm happier. I sometimes choose to research or write legal motions and briefs Saturday and Sunday mornings so I can send my final product off to a client or file it in a court early, leaving the rest of the week for revising the third thriller in my Awakening series. Likewise, I might grade the papers my law students write while taking Amtrak to visit family, despite that it's officially vacation, because it helps pass the long train ride. Or I'll sit out on my deck and dictate parts of a blog post into my phone while watching a beautiful sunset, which is how I began this entry.At first I struggled against this migration of work into evenings and weekends--those times I'd tried so hard, often without success, to keep sacred when I labored primarily at law. But being too rigid led to me feeling both busier and as if I weren't getting as much done, as I always felt I ought to be doing something else. Paying bills during 9-5 when I'm most sharp and productive seemed like a waste, as did going to the grocery store during evenings or weekends when everyone else is there. When I felt freer to handle tasks when I'd be most productive at them or enjoy them more regardless of the time or place, I discovered I found it easier to relax during downtime, plus I had more of it. Letting myself open my laptop on a Saturday morning to rewrite a scene that had sifted through my mind during the night gave me more than one uninterrupted hour to read a novel during the week. Immersing myself in reading that way is something I loved from childhood on but hadn't done regularly since before I'd started law school. From then on, reading for pleasure happened only in 10-20 minute increments unless I was on vacation.

------------------------------------------------------------------Join Lisa M. Lilly's M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) Reader Group and receive Ninevah, a short horror story published exclusively for subscribers, free. Your email address will never be shared or sold.-------------------------------------------------------------------Now I wonder if, while I was practicing law full time, I might have been happier had I allowed myself the same flexibility. I liked my work, and I loved running my own business. But I got depressed, feeling like the only person in the whole world working when I stayed at my office every night until 7 p.m. At the big law firm where I'd practiced, seven was a normal time to leave work, but on my own most of the people where I shared offices left by 5 or 6. And on weekends, it was just me and the security guards. I might have felt happier doing routine administrative tasks at home with a glass of wine and John Fogerty playing on the stereo.

One of the things I do identify with that Joanna Penn said is that because she loves writing and everything connected to it, her leisure time and social interactions all often relate to her work, and she enjoys that. Authors need to read, and that's a great love of mine. I've also made very close friends at writing conferences and more recently through writing communities on line. We've become sounding boards for one another for our careers and for other parts of life. Plus we have fun. I recently had a great time eating good food and drinking wine at Lady Gregory in Chicago with my friend Patty, who runs Path to Essential Health. Yet we were having a business meeting about a creativity workshop we're putting together.

At the same time, I remember when I started my law firm I was also delighted at the many ways business and social came together. At the large firm, the hours of legal work required to meet guidelines left little time for any type of social life--business related or not. On my own, I was thrilled that I could eat lunch often with friends, attend bar association events, and host get togethers at my firm. That a side effect often was sharing good business advice or connecting one another with potential clients or vendors was icing on the cake. Three or four years later, though, when my practice had grown almost beyond me, I felt burnt out and tired. I still loved seeing my friends, but the hours in the office felt less rewarding, and I began to resent the lack of time away.

It's tempting to believe that'll never happen with my writing, and with the business side of writing, because I love it more. And that's probably true in part. But the author of The E-Myth Revisted, a book about entrepreneurs with small businesses, talks about the dangers of growth without a plan. The author gives examples of small business owners who survive the all important first five years (during which most small business fail) only to confront a challenge they never expected: too much success, resulting in working too much for too long and no longer loving the business. I recognized myself right away and realized that within a year of opening my doors I ought to have hired a full time legal assistant rather than doing so much myself with office support only on a project basis.

I plan to learn from that experience, so much as I love writing and everything connected with it, I'll make a a little nod to work/life balance more often than I feel the need to. Also thanks to Joanna's podcast, I've started scheduling my tasks for the following work day the night before. It helps me get more done and, as important, I schedule in breaks and I know when I'm finished for the day. And I'm keeping an eye on what additional aspects of my writing business and law practice I will outsource if I hit a point where I feel all I do is work.

What about you? Does whether you love your work affect your need for work/life balance? What tips can you offer on enjoying your life inside and outside of work?

---------------

Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. A short film of the title story of her collection The Tower Formerly Known as Sears and Two Other Tales of Urban Horror was recently produced under the title Willis Tower.

Published on September 01, 2015 14:55

July 7, 2015

Listening to Fiction and Talking with Shiromi Arserio

I'm one of those people who thought I would never read on an electronic device. I love paper books. During the four years I worked full time and attended law school at night, on those rare days I took off from both, I wandered book stores. I scanned titles in all their fabulous and varied fonts, ran my hands over book covers, inhaled the combined smell of paper and ink. So I had a certain amount of sympathy when a friend said she would never buy a Kindle, because there was no problem there that needed fixing. Books were perfect as is.

Yet I love the Kindle, too. The ideal vacation for me is a pool, a view of the ocean, and a giant stack of books. (Plus, as you might guess from my photo, a lot of SPF 50 sunscreen.) The Kindle allowed me to not only bring that stack on one small device but to order more with a click. The first time I finished a series and ordered the next, I felt just like a mouse must presented with the lever to get more cheese. Click, click, click.

Enter audiobooks. I bought a Kindle when I decided to publish my thriller The Awakening on it. I felt I ought to know what that reading experience was like. Similarly, a while back, I began hearing more about authors and publishers releasing audiobooks. I was skeptical. My experience was with tapes (yes, I'm old enough for that) and CDs that I bought, aspired to listen to, and never did. I couldn't imagine that I'd ever buy more than one or two audiobooks. Or listen to podcasts for that matter.

Enter audiobooks. I bought a Kindle when I decided to publish my thriller The Awakening on it. I felt I ought to know what that reading experience was like. Similarly, a while back, I began hearing more about authors and publishers releasing audiobooks. I was skeptical. My experience was with tapes (yes, I'm old enough for that) and CDs that I bought, aspired to listen to, and never did. I couldn't imagine that I'd ever buy more than one or two audiobooks. Or listen to podcasts for that matter.

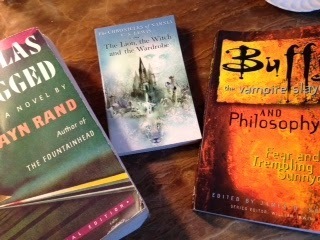

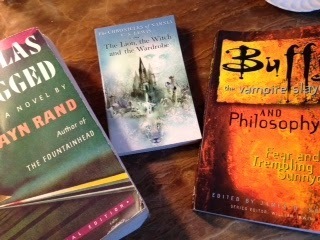

Now I listen to one or the other frequently on my iPhone during the day using the Audible app. (My favorite podcast is Dusted by Storywonk, which analyzes Buffy the Vampire Slayer episodes.) When I read, I do so to shut off everything else. But with an audiobook, I listen to accompany other tasks, and compelling books motivate me to continue whatever I'm doing so I can hear more. If I'm listening to a book a I love, my condo is very, very clean, my bills are paid well in advance, and my checkbook is balanced. And I'm in great shape, as treadmills are wonderful for listening.

------------------------------------------------------------------Would you like to receive Lisa M. Lilly's e-newsletter with M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) book and film reviews? Your email address will not be shared or sold. Join here today and you'll also receive Ninevah, a short story exclusively for subscribers.-------------------------------------------------------------------For both listening and reading, I enjoy thrillers because they pull me right in and keep me engaged. I also like non-fiction on audio, but if the concepts are too complex, that doesn't work. On paper, I can slow down or reread a paragraph and ponder it. While Audible allows skipping back 30 seconds at a time, that doesn't match seeing words on the page or easily flipping through an earlier section.

Given the differences I experienced in reading versus listening, I became curious about how narrating an audiobook differs from other types of performances. So I asked producer/narrator Shiromi Arserio.

Shiromi and I have similar tastes. I wanted to work with her on The Unbelievers, Book 2 in my series, because one of the first audiobooks I ever listened to, a sci fi thriller with a female main character, was one she narrated. I also was very excited that Shiromi has appeared in a few Lost episodes. (Which has nothing to do with producing audiobooks, I just thought it was cool.) And we both love Michael Biehn, the actor who played Kyle Reese in the first Terminator movie. Cyril Woods, the antagonist/almost love interest in The Awakening is modeled a tiny bit after Biehn's portrayal of Reese, so I knew Shiromi would understand how I saw and heard Cyril.

Her answers to my questions are below. (Notice how I didn't ask her what things about working with authors drive her crazy or make her want to throw things.)

Are the skills you need for narrating different from those you use when acting?

When you're acting, even if it's for a video game, you're playing one character at a time. In an audiobook you are doing an entire play by yourself. Jumping from male to female characters, changing accents. It's a lot to keep track of. Also, as a narrator, you have to remember that it's not about the actor's performance. You want someone to remember how good the story is, not how memorable the actor was.

When you read a book you’re preparing to narrate, do you hear each character’s voice in your mind? Do you need to think about it for a while?

Some characters pop in my head fully formed. I have a clear idea who the character is and how they should sound. Sometimes I’ll have to go away and think about it. Maybe get the author's input, if I can. The more well-developed the character is on the page, the easier it is to “hear” the voice.

How do you handle a character’s interior thoughts? Is it hard to differentiate that from dialogue?

Interior thoughts can be really challenging. For one of my early books I used a slight reverb effect to change the sound of the thoughts, but it's time consuming and generally ACX (the production platform) doesn’t approve of effects in audiobooks. And most people are listening through tiny headphones while on the way to work or going for a run, and can't even hear the reverb. So now I just get a little closer to the mic and drop my voice as though I'm talking to myself.

What is your favorite type of book to read? To listen to? Is there a difference between the two when it comes to favorites?

I'm a geek, so I love to read or listen to scifi, horror, fantasy. However, with audiobooks I tend to go for ones that are more involved. There are certain books that I just process easier listening to rather than reading. The A Song of Ice and Fire series is like that for me. I read Game of Thrones, but it was a bit of a slog. The first time I read it, I kept losing my place and not realising I’d jumped ahead. Listening to Roy Dotrice's narration became a much more enjoyable way to experience Westeros.

Do you have a type of listener or a particular person in mind when you narrate, a sort of ideal audience, the way some authors do when they write? Who is that person?

I don't necessarily have an ideal listener. To be honest, usually I find myself getting lost in the story. But when I am thinking about the listener and how I’m telling the story, I try to imagine that he or she is sitting right here with me. I'll glance over to a spot in my booth, like I’m making eye contact, just as I would if I were telling a story in person.

I enjoyed working with Shiromi throughout the production of The Unbelievers, which was released a few days ago. (You can listen to a sample of Shiromi's narration of the book here). She currently has a handful of audiobooks in various stages of production, and she also does a lot of video game work. In a game called Infinifactory, where you build "factories that assemble products for your alien overlords, and try not to die in the process," she plays four different characters.

What about you? What do you do while listening to audiobooks, and what types do you like best? If you're an author or narrator, what experiences have you had?

-------------------------

Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. Both are available in paperback and ebook editions and as audiobooks on Amazon or Audible. She is currently working on Book 3 in the four-book series.

Yet I love the Kindle, too. The ideal vacation for me is a pool, a view of the ocean, and a giant stack of books. (Plus, as you might guess from my photo, a lot of SPF 50 sunscreen.) The Kindle allowed me to not only bring that stack on one small device but to order more with a click. The first time I finished a series and ordered the next, I felt just like a mouse must presented with the lever to get more cheese. Click, click, click.

Enter audiobooks. I bought a Kindle when I decided to publish my thriller The Awakening on it. I felt I ought to know what that reading experience was like. Similarly, a while back, I began hearing more about authors and publishers releasing audiobooks. I was skeptical. My experience was with tapes (yes, I'm old enough for that) and CDs that I bought, aspired to listen to, and never did. I couldn't imagine that I'd ever buy more than one or two audiobooks. Or listen to podcasts for that matter.

Enter audiobooks. I bought a Kindle when I decided to publish my thriller The Awakening on it. I felt I ought to know what that reading experience was like. Similarly, a while back, I began hearing more about authors and publishers releasing audiobooks. I was skeptical. My experience was with tapes (yes, I'm old enough for that) and CDs that I bought, aspired to listen to, and never did. I couldn't imagine that I'd ever buy more than one or two audiobooks. Or listen to podcasts for that matter.Now I listen to one or the other frequently on my iPhone during the day using the Audible app. (My favorite podcast is Dusted by Storywonk, which analyzes Buffy the Vampire Slayer episodes.) When I read, I do so to shut off everything else. But with an audiobook, I listen to accompany other tasks, and compelling books motivate me to continue whatever I'm doing so I can hear more. If I'm listening to a book a I love, my condo is very, very clean, my bills are paid well in advance, and my checkbook is balanced. And I'm in great shape, as treadmills are wonderful for listening.

------------------------------------------------------------------Would you like to receive Lisa M. Lilly's e-newsletter with M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) book and film reviews? Your email address will not be shared or sold. Join here today and you'll also receive Ninevah, a short story exclusively for subscribers.-------------------------------------------------------------------For both listening and reading, I enjoy thrillers because they pull me right in and keep me engaged. I also like non-fiction on audio, but if the concepts are too complex, that doesn't work. On paper, I can slow down or reread a paragraph and ponder it. While Audible allows skipping back 30 seconds at a time, that doesn't match seeing words on the page or easily flipping through an earlier section.

Given the differences I experienced in reading versus listening, I became curious about how narrating an audiobook differs from other types of performances. So I asked producer/narrator Shiromi Arserio.

Shiromi and I have similar tastes. I wanted to work with her on The Unbelievers, Book 2 in my series, because one of the first audiobooks I ever listened to, a sci fi thriller with a female main character, was one she narrated. I also was very excited that Shiromi has appeared in a few Lost episodes. (Which has nothing to do with producing audiobooks, I just thought it was cool.) And we both love Michael Biehn, the actor who played Kyle Reese in the first Terminator movie. Cyril Woods, the antagonist/almost love interest in The Awakening is modeled a tiny bit after Biehn's portrayal of Reese, so I knew Shiromi would understand how I saw and heard Cyril.

Her answers to my questions are below. (Notice how I didn't ask her what things about working with authors drive her crazy or make her want to throw things.)

Are the skills you need for narrating different from those you use when acting?

When you're acting, even if it's for a video game, you're playing one character at a time. In an audiobook you are doing an entire play by yourself. Jumping from male to female characters, changing accents. It's a lot to keep track of. Also, as a narrator, you have to remember that it's not about the actor's performance. You want someone to remember how good the story is, not how memorable the actor was.

When you read a book you’re preparing to narrate, do you hear each character’s voice in your mind? Do you need to think about it for a while?

Some characters pop in my head fully formed. I have a clear idea who the character is and how they should sound. Sometimes I’ll have to go away and think about it. Maybe get the author's input, if I can. The more well-developed the character is on the page, the easier it is to “hear” the voice.

How do you handle a character’s interior thoughts? Is it hard to differentiate that from dialogue?

Interior thoughts can be really challenging. For one of my early books I used a slight reverb effect to change the sound of the thoughts, but it's time consuming and generally ACX (the production platform) doesn’t approve of effects in audiobooks. And most people are listening through tiny headphones while on the way to work or going for a run, and can't even hear the reverb. So now I just get a little closer to the mic and drop my voice as though I'm talking to myself.

What is your favorite type of book to read? To listen to? Is there a difference between the two when it comes to favorites?

I'm a geek, so I love to read or listen to scifi, horror, fantasy. However, with audiobooks I tend to go for ones that are more involved. There are certain books that I just process easier listening to rather than reading. The A Song of Ice and Fire series is like that for me. I read Game of Thrones, but it was a bit of a slog. The first time I read it, I kept losing my place and not realising I’d jumped ahead. Listening to Roy Dotrice's narration became a much more enjoyable way to experience Westeros.

Do you have a type of listener or a particular person in mind when you narrate, a sort of ideal audience, the way some authors do when they write? Who is that person?

I don't necessarily have an ideal listener. To be honest, usually I find myself getting lost in the story. But when I am thinking about the listener and how I’m telling the story, I try to imagine that he or she is sitting right here with me. I'll glance over to a spot in my booth, like I’m making eye contact, just as I would if I were telling a story in person.

I enjoyed working with Shiromi throughout the production of The Unbelievers, which was released a few days ago. (You can listen to a sample of Shiromi's narration of the book here). She currently has a handful of audiobooks in various stages of production, and she also does a lot of video game work. In a game called Infinifactory, where you build "factories that assemble products for your alien overlords, and try not to die in the process," she plays four different characters.

What about you? What do you do while listening to audiobooks, and what types do you like best? If you're an author or narrator, what experiences have you had?

-------------------------

Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. Both are available in paperback and ebook editions and as audiobooks on Amazon or Audible. She is currently working on Book 3 in the four-book series.

Published on July 07, 2015 14:28

June 30, 2015

Are Books Written by Women More Likely to be Labeled "Trash"?

Have you ever heard someone say with an air of apology, “I read trash”? Or has anyone dismissed what you read that way? Once a friend referred to an early Mary Higgins Clark book as trash. If Clark has heard her work called that, I imagine she doesn’t lose sleep over it given that she’s known as the Queen of Suspense, has sold over 100 million books in her lifetime, and receives advances of over $10 million per novel. But the comment made me wonder, what is it that makes one book or author more likely than another to be labeled trash?

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”

For those not that familiar with the two novels, Fifty Shades was initially self-published as an e-book in 2011. It is about a young woman who is a virgin. Her first sexual relationship is with a man whose proclivities include bondage and discipline. In One Person was traditionally published. Written as if it were a memoir of a man in his sixties or seventies, it focuses on the narrator’s first sexual relationship, which is with a transsexual (this is the word the author uses), as well as his many subsequent sexual experiences as he matures. I did not like either book. After the first chapter, I skimmed both. The critiques I listed above I had about both books. Yet E.L. James (the pen name of the Fifty Shades author) is generally considered a writer of trash and John Irving is lauded as a literary giant.

Here are my ideas about why:

------------------------------------------------------------------Ninevah: a free short horror story published exclusively for Lisa M. Lilly's subscribersclick here to join email list and receive your free copy -------------------------------------------------------------------

Emotional Distance or Closeness: One reason I don’t like many literary novels is that, as with Irving’s book, I often feel disconnected from the characters. While I didn’t love Fifty Shades, I had no doubt how narrator Anastasia felt about her love interest, her life, her sex life, her friends, etc. I had empathy for her. In contrast, I never quite feel what Irving’s main character, whose name I’ve forgotten, feels. His sex scenes are detailed to say the least—I’ve never read or heard anything that included so many uses of words for male and female anatomy—but, to me, not compelling. They are told with a tone of irony and detached observation. Most novels I was required to read in high school and college had that type of distance between the author’s voice and the characters. Most were written using an omniscient narrator. In that style, the narrator knows all about everything, sometimes even intruding and commenting on the plot or the characters’ choices, but stays a bit removed and above it all. Current fiction tends to set the reader right in the characters’ hearts and minds. I think this has led to associating “literature” with distance and popular fiction (which for some equals “trash”) with emotional connection. Though certainly there are literary writers, such as Dorothy Allison, whose work I find almost too hard to read due to the depth of the characters’ emotions.

Guilt/Entertainment: Many people feel guilty about enjoying reading. If a book is fun and they can’t put it down, they believe it must not have literary merit. On the other hand, if most people groan when they hear the title and say, “Ugh, yeah, I had to read that in school,” or if at the very least it takes effort and planning to get yourself to sit on the couch and open it, then a novel must be good, it must be literary. So a fast read like a Jonathan Kellerman or a Mary Higgins Clark is trash, and a novel that plods along where you don’t care one way or another about the characters must be literary. Again, I think this is a holdover from high school and college.

What the Book is About: I don’t mean the subject of the main storyline. In One Person and Fifty Shades of Grey are both about sexual awakening and experiences. But the former also explores sociological and political questions such as how the main character’s family responds to him and his orientation, what role heredity and environment may or may not play in sexuality, and how society treated and treats people who are bisexual. In contrast, for the most part, Fifty Shades focuses on the personal relationship between Anastasia and her love interest and leaves larger questions about society untouched. This is not to say that a reader couldn’t extrapolate from Anastasia’s experiences and feelings to a larger theme, but, to me at least, that isn’t in the text of the book. (Perhaps this is why I saw Irving’s book referred to as “literary porn,” while Fifty Shades is often called “mommy porn.”) This criteria is one that, for me, often divides what I think of as pure of-the-moment entertainment versus a book that makes me keep thinking about it long after I’ve finished. But I’ve felt this way about both books that are considered literary and those that are considered genre or mainstream fiction, such as certain Stephen King novels, my favorite being The Dead Zone.

The Education Needed to Read And Understand the Book: By education, I don’t mean level in school, but the breadth of knowledge a person needs to understand the book. I suspect this is a principal reason Shakespeare was considered entertainment for the masses when originally performed and is now considered literary. For most of us, enjoying Shakespeare’s plays takes a certain amount of knowledge of the times in which they were written and the changes in the language since then. That can be gained through reading an annotated text or joining literature classes or discussion groups, but it takes more effort than, say, a detective novel. So readers of Shakespeare and similar books may see themselves as smarter, more educated, and more like serious readers even if they only read a few books a year, while I tend to think of serious readers as those who love to read book after book after book.

The Gender of the Author and the Main Character: Look at any overall list of best literary fiction and you’ll find it dominated by men, and white men at that. This is starting to change, so now you’ll find women writers and writers of color included in literary book lists for recent years. All the same, being male helps if you want to be considered a serious author. Something else I’ve noticed is that a coming of age book about a young woman is generally considered a genre or young adult book (think Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret, or anything else by Judy Blume if you’re my age or the Hunger Games or Divergent novels), and thus, to some people, a lesser sort of book—a sentiment with which I disagree. A coming of age book about a young man, however, is often considered literary. Think about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Catcher in the Rye. There are exceptions; for instance, I found To Kill a Mockingbird on one list of literary coming of age novels (along with 9 books about boys/men). Likewise, when women write about sexual or romantic love, by and large it is considered trash—think of the view of most everyone you know about romance or “women’s” novels. When men write about sexual exploits, though, it is literary. Ask Vladimir Nabokov and John Irving.

------------------------------------------------------------------Would you like to receive Lisa M. Lilly's e-newsletter with M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) book and film reviews? Your email address will not be shared or sold.Join here. ------------------------------------------------------------------

The Track Record of the Author: This is the one that probably applies most directly to the two books I’ve been comparing. Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction (fiction where the writer adopts characters of an already existing book, movie, or television show) based on the Twilight series. The author was an unknown in the fiction world. Only after she self-published it as an e-book and it became wildly popular did a traditional publisher take it on. John Irving, in contrast, had twelve novels published before In One Person, for the most part to critical acclaim. Based on his pedigree, I assumed when reading In One Person that Irving deliberately chose for stylistic reasons to have the narrator retell various anecdotes and refer to his uncle and other characters a gazillion times by nicknames such as “The Racket Man.” (Or “racquetman,” I’m not sure, as I listened rather than read and didn’t care enough about any of the characters to track it down or figure it out from context.) On the other hand, knowing the history of Fifty Shades of Grey, I assumed that when the entire contract between the narrator and her love interest was included word-for-word more than once, it was because the story initially had been told in serial fashion, so the author had repeated it for readers who hadn’t started at the beginning, then not thought to edit it out when transforming the work into one complete novel. Similarly, I ascribed catch phrases that made me cringe to inexperienced writing. In short, while I didn’t like either writing style, I concluded Irving was trying to achieve an effect that just didn’t work for me, while E.L. James’ novel needed another round or two of rewriting or editing. Accurate in either case? Maybe, maybe not.

As to for my own writing, as in reading fiction, plot matters to me most, then character, then the writing style, but I strive for all three to be as strong as possible. And I don’t consider anything I read “trash,” just a book or style or subject that’s not for me. What about you? Do read—or write—anything you would call trash? If so, what does that mean to you?

-----------------

Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. A short film of the title story of her collection The Tower Formerly Known as Sears and Two Other Tales of Urban Horror was produced under the title Willis Tower. If you'd like to be notified of new releases and read reviews of M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) books and movies click here.

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”For those not that familiar with the two novels, Fifty Shades was initially self-published as an e-book in 2011. It is about a young woman who is a virgin. Her first sexual relationship is with a man whose proclivities include bondage and discipline. In One Person was traditionally published. Written as if it were a memoir of a man in his sixties or seventies, it focuses on the narrator’s first sexual relationship, which is with a transsexual (this is the word the author uses), as well as his many subsequent sexual experiences as he matures. I did not like either book. After the first chapter, I skimmed both. The critiques I listed above I had about both books. Yet E.L. James (the pen name of the Fifty Shades author) is generally considered a writer of trash and John Irving is lauded as a literary giant.

Here are my ideas about why:

------------------------------------------------------------------Ninevah: a free short horror story published exclusively for Lisa M. Lilly's subscribersclick here to join email list and receive your free copy -------------------------------------------------------------------

Emotional Distance or Closeness: One reason I don’t like many literary novels is that, as with Irving’s book, I often feel disconnected from the characters. While I didn’t love Fifty Shades, I had no doubt how narrator Anastasia felt about her love interest, her life, her sex life, her friends, etc. I had empathy for her. In contrast, I never quite feel what Irving’s main character, whose name I’ve forgotten, feels. His sex scenes are detailed to say the least—I’ve never read or heard anything that included so many uses of words for male and female anatomy—but, to me, not compelling. They are told with a tone of irony and detached observation. Most novels I was required to read in high school and college had that type of distance between the author’s voice and the characters. Most were written using an omniscient narrator. In that style, the narrator knows all about everything, sometimes even intruding and commenting on the plot or the characters’ choices, but stays a bit removed and above it all. Current fiction tends to set the reader right in the characters’ hearts and minds. I think this has led to associating “literature” with distance and popular fiction (which for some equals “trash”) with emotional connection. Though certainly there are literary writers, such as Dorothy Allison, whose work I find almost too hard to read due to the depth of the characters’ emotions.

Guilt/Entertainment: Many people feel guilty about enjoying reading. If a book is fun and they can’t put it down, they believe it must not have literary merit. On the other hand, if most people groan when they hear the title and say, “Ugh, yeah, I had to read that in school,” or if at the very least it takes effort and planning to get yourself to sit on the couch and open it, then a novel must be good, it must be literary. So a fast read like a Jonathan Kellerman or a Mary Higgins Clark is trash, and a novel that plods along where you don’t care one way or another about the characters must be literary. Again, I think this is a holdover from high school and college.

What the Book is About: I don’t mean the subject of the main storyline. In One Person and Fifty Shades of Grey are both about sexual awakening and experiences. But the former also explores sociological and political questions such as how the main character’s family responds to him and his orientation, what role heredity and environment may or may not play in sexuality, and how society treated and treats people who are bisexual. In contrast, for the most part, Fifty Shades focuses on the personal relationship between Anastasia and her love interest and leaves larger questions about society untouched. This is not to say that a reader couldn’t extrapolate from Anastasia’s experiences and feelings to a larger theme, but, to me at least, that isn’t in the text of the book. (Perhaps this is why I saw Irving’s book referred to as “literary porn,” while Fifty Shades is often called “mommy porn.”) This criteria is one that, for me, often divides what I think of as pure of-the-moment entertainment versus a book that makes me keep thinking about it long after I’ve finished. But I’ve felt this way about both books that are considered literary and those that are considered genre or mainstream fiction, such as certain Stephen King novels, my favorite being The Dead Zone.

The Education Needed to Read And Understand the Book: By education, I don’t mean level in school, but the breadth of knowledge a person needs to understand the book. I suspect this is a principal reason Shakespeare was considered entertainment for the masses when originally performed and is now considered literary. For most of us, enjoying Shakespeare’s plays takes a certain amount of knowledge of the times in which they were written and the changes in the language since then. That can be gained through reading an annotated text or joining literature classes or discussion groups, but it takes more effort than, say, a detective novel. So readers of Shakespeare and similar books may see themselves as smarter, more educated, and more like serious readers even if they only read a few books a year, while I tend to think of serious readers as those who love to read book after book after book.

The Gender of the Author and the Main Character: Look at any overall list of best literary fiction and you’ll find it dominated by men, and white men at that. This is starting to change, so now you’ll find women writers and writers of color included in literary book lists for recent years. All the same, being male helps if you want to be considered a serious author. Something else I’ve noticed is that a coming of age book about a young woman is generally considered a genre or young adult book (think Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret, or anything else by Judy Blume if you’re my age or the Hunger Games or Divergent novels), and thus, to some people, a lesser sort of book—a sentiment with which I disagree. A coming of age book about a young man, however, is often considered literary. Think about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Catcher in the Rye. There are exceptions; for instance, I found To Kill a Mockingbird on one list of literary coming of age novels (along with 9 books about boys/men). Likewise, when women write about sexual or romantic love, by and large it is considered trash—think of the view of most everyone you know about romance or “women’s” novels. When men write about sexual exploits, though, it is literary. Ask Vladimir Nabokov and John Irving.

------------------------------------------------------------------Would you like to receive Lisa M. Lilly's e-newsletter with M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) book and film reviews? Your email address will not be shared or sold.Join here. ------------------------------------------------------------------

The Track Record of the Author: This is the one that probably applies most directly to the two books I’ve been comparing. Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction (fiction where the writer adopts characters of an already existing book, movie, or television show) based on the Twilight series. The author was an unknown in the fiction world. Only after she self-published it as an e-book and it became wildly popular did a traditional publisher take it on. John Irving, in contrast, had twelve novels published before In One Person, for the most part to critical acclaim. Based on his pedigree, I assumed when reading In One Person that Irving deliberately chose for stylistic reasons to have the narrator retell various anecdotes and refer to his uncle and other characters a gazillion times by nicknames such as “The Racket Man.” (Or “racquetman,” I’m not sure, as I listened rather than read and didn’t care enough about any of the characters to track it down or figure it out from context.) On the other hand, knowing the history of Fifty Shades of Grey, I assumed that when the entire contract between the narrator and her love interest was included word-for-word more than once, it was because the story initially had been told in serial fashion, so the author had repeated it for readers who hadn’t started at the beginning, then not thought to edit it out when transforming the work into one complete novel. Similarly, I ascribed catch phrases that made me cringe to inexperienced writing. In short, while I didn’t like either writing style, I concluded Irving was trying to achieve an effect that just didn’t work for me, while E.L. James’ novel needed another round or two of rewriting or editing. Accurate in either case? Maybe, maybe not.

As to for my own writing, as in reading fiction, plot matters to me most, then character, then the writing style, but I strive for all three to be as strong as possible. And I don’t consider anything I read “trash,” just a book or style or subject that’s not for me. What about you? Do read—or write—anything you would call trash? If so, what does that mean to you?

-----------------

Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. A short film of the title story of her collection The Tower Formerly Known as Sears and Two Other Tales of Urban Horror was produced under the title Willis Tower. If you'd like to be notified of new releases and read reviews of M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) books and movies click here.

Published on June 30, 2015 15:49

Do You Read Trash?

Have you ever heard someone say with an air of apology, “I read trash”? Or has anyone dismissed what you read that way? Once a friend referred to an early Mary Higgins Clark book as trash. If Clark has heard her work called that, I imagine she doesn’t lose sleep over it given that she’s known as the Queen of Suspense, has sold over 100 million books in her lifetime, and receives advances of over $10 million per novel. But the comment made me wonder, what is it that makes one book or author more likely than another to be labeled trash?

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”

For those not that familiar with the two novels, Fifty Shades was initially self-published as an e-book in 2011. It is about a young woman who is a virgin. Her first sexual relationship is with a man whose proclivities include bondage and discipline. In One Person was traditionally published. Written as if it were a memoir of a man in his sixties or seventies, it focuses on the narrator’s first sexual relationship, which is with a transsexual (this is the word the author uses), as well as his many subsequent sexual experiences as he matures. I did not like either book. After the first chapter, I skimmed both. The critiques I listed above I had about both books. Yet E.L. James (the pen name of the Fifty Shades author) is generally considered a writer of trash and John Irving is lauded as a literary giant.

Here are my ideas about why:

------------------------------------------------------------------Receive a free short horror story published exclusively for Lisa M. Lilly's subscribers. Ninevah: When new management takes over, one woman must cast her lot with the incoming regime or get out while she can. The consequences of her choice may be worse she ever could have imagined....click here to join and receive your free copy. -------------------------------------------------------------------

Emotional Distance or Closeness: One reason I don’t like many literary novels is that, as with Irving’s book, I often feel disconnected from the characters. While I didn’t love Fifty Shades, I had no doubt how narrator Anastasia felt about her love interest, her life, her sex life, her friends, etc. I had empathy for her. In contrast, I never quite feel what Irving’s main character, whose name I’ve forgotten, feels. His sex scenes are detailed to say the least—I’ve never read or heard anything that included so many uses of words for male and female anatomy—but, to me, not compelling. They are told with a tone of irony and detached observation. Most novels I was required to read in high school and college had that type of distance between the author’s voice and the characters. Most were written using an omniscient narrator. In that style, the narrator knows all about everything, sometimes even intruding and commenting on the plot or the characters’ choices, but stays a bit removed and above it all. Current fiction tends to set the reader right in the characters’ hearts and minds. I think this has led to associating “literature” with distance and popular fiction (which for some equals “trash”) with emotional connection. Though certainly there are literary writers, such as Dorothy Allison, whose work I find almost too hard to read due to the depth of the characters’ emotions.

Guilt/Entertainment: Many people feel guilty about enjoying reading. If a book is fun and they can’t put it down, they believe it must not have literary merit. On the other hand, if most people groan when they hear the title and say, “Ugh, yeah, I had to read that in school,” or if at the very least it takes effort and planning to get yourself to sit on the couch and open it, then a novel must be good, it must be literary. So a fast read like a Jonathan Kellerman or a Mary Higgins Clark is trash, and a novel that plods along where you don’t care one way or another about the characters must be literary. Again, I think this is a holdover from high school and college.

What the Book is About: I don’t mean the subject of the main storyline. In One Person and Fifty Shades of Grey are both about sexual awakening and experiences. But the former also explores sociological and political questions such as how the main character’s family responds to him and his orientation, what role heredity and environment may or may not play in sexuality, and how society treated and treats people who are bisexual. In contrast, for the most part, Fifty Shades focuses on the personal relationship between Anastasia and her love interest and leaves larger questions about society untouched. This is not to say that a reader couldn’t extrapolate from Anastasia’s experiences and feelings to a larger theme, but, to me at least, that isn’t in the text of the book. (Perhaps this is why I saw Irving’s book referred to as “literary porn,” while Fifty Shades is often called “mommy porn.”) This criteria is one that, for me, often divides what I think of as pure of-the-moment entertainment versus a book that makes me keep thinking about it long after I’ve finished. But I’ve felt this way about both books that are considered literary and those that are considered genre or mainstream fiction, such as certain Stephen King novels, my favorite being The Dead Zone.

The Education Needed to Read And Understand the Book: By education, I don’t mean level in school, but the breadth of knowledge a person needs to understand the book. I suspect this is a principal reason Shakespeare was considered entertainment for the masses when originally performed and is now considered literary. For most of us, enjoying Shakespeare’s plays takes a certain amount of knowledge of the times in which they were written and the changes in the language since then. That can be gained through reading an annotated text or joining literature classes or discussion groups, but it takes more effort than, say, a detective novel. So readers of Shakespeare and similar books may see themselves as smarter, more educated, and more like serious readers even if they only read a few books a year, while I tend to think of serious readers as those who love to read book after book after book.

The Gender of the Author and the Main Character: Look at any overall list of best literary fiction and you’ll find it dominated by men, and white men at that. This is starting to change, so now you’ll find women writers and writers of color included in literary book lists for recent years. All the same, being male helps if you want to be considered a serious author. Something else I’ve noticed is that a coming of age book about a young woman is generally considered a genre or young adult book (think Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret, or anything else by Judy Blume if you’re my age or the Hunger Games or Divergent novels), and thus, to some people, a lesser sort of book—a sentiment with which I disagree. A coming of age book about a young man, however, is often considered literary. Think about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Catcher in the Rye. There are exceptions; for instance, I found To Kill a Mockingbird on one list of literary coming of age novels (along with 9 books about boys/men). Likewise, when women write about sexual or romantic love, by and large it is considered trash—think of the view of most everyone you know about romance or “women’s” novels. When men write about sexual exploits, though, it is literary. Ask Vladimir Nabokov and John Irving.

------------------------------------------------------------------Would you like to receive Lisa M. Lilly's e-newsletter with M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) book and film reviews? Your email address will not be shared or sold.Join here. ------------------------------------------------------------------

The Track Record of the Author: This is the one that probably applies most directly to the two books I’ve been comparing. Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction (fiction where the writer adopts characters of an already existing book, movie, or television show) based on the Twilight series. The author was an unknown in the fiction world. Only after she self-published it as an e-book and it became wildly popular did a traditional publisher take it on. John Irving, in contrast, had twelve novels published before In One Person, for the most part to critical acclaim. Based on his pedigree, I assumed when reading In One Person that Irving deliberately chose for stylistic reasons to have the narrator retell various anecdotes and refer to his uncle and other characters a gazillion times by nicknames such as “The Racket Man.” (Or “racquetman,” I’m not sure, as I listened rather than read and didn’t care enough about any of the characters to track it down or figure it out from context.) On the other hand, knowing the history of Fifty Shades of Grey, I assumed that when the entire contract between the narrator and her love interest was included word-for-word more than once, it was because the story initially had been told in serial fashion, so the author had repeated it for readers who hadn’t started at the beginning, then not thought to edit it out when transforming the work into one complete novel. Similarly, I ascribed catch phrases that made me cringe to inexperienced writing. In short, while I didn’t like either writing style, I concluded Irving was trying to achieve an effect that just didn’t work for me, while E.L. James’ novel needed another round or two of rewriting or editing. Accurate in either case? Maybe, maybe not.

As to for my own writing, as in reading fiction, plot matters to me most, then character, then the writing style, but I strive for all three to be as strong as possible. And I don’t consider anything I read “trash,” just a book or style or subject that’s not for me. What about you? Do read—or write—anything you would call trash? If so, what does that mean to you?

----------------- Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. A short film of the title story of her collection The Tower Formerly Known as Sears and Two Other Tales of Urban Horror was produced under the title Willis Tower. If you'd like to be notified of new releases and read reviews of M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) books and movies click here.

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”

It seems like some subjects, genres, or aspects of writing should make the distinction easy to draw, but I suspect other not so obvious factors are at work. For example, last month my women’s book group read a book I normally would never have picked up. It’s a coming of age novel told by a first person narrator. The story, to the extent there is one, revolves around sexual tastes and practices the general public considers unusual. The dialogue struck me as preposterous, and the narrative includes annoying catch phrases and repetition. All my critiques makes this sounds like a book in one of those genres that’s most often labeled trash, such as erotica or romance. Fifty Shades of Grey, perhaps. But no, what I read was In One Person by John Irving. After the book was released in 2012, Time magazine called Irving a “literary legend.”For those not that familiar with the two novels, Fifty Shades was initially self-published as an e-book in 2011. It is about a young woman who is a virgin. Her first sexual relationship is with a man whose proclivities include bondage and discipline. In One Person was traditionally published. Written as if it were a memoir of a man in his sixties or seventies, it focuses on the narrator’s first sexual relationship, which is with a transsexual (this is the word the author uses), as well as his many subsequent sexual experiences as he matures. I did not like either book. After the first chapter, I skimmed both. The critiques I listed above I had about both books. Yet E.L. James (the pen name of the Fifty Shades author) is generally considered a writer of trash and John Irving is lauded as a literary giant.

Here are my ideas about why:

------------------------------------------------------------------Receive a free short horror story published exclusively for Lisa M. Lilly's subscribers. Ninevah: When new management takes over, one woman must cast her lot with the incoming regime or get out while she can. The consequences of her choice may be worse she ever could have imagined....click here to join and receive your free copy. -------------------------------------------------------------------

Emotional Distance or Closeness: One reason I don’t like many literary novels is that, as with Irving’s book, I often feel disconnected from the characters. While I didn’t love Fifty Shades, I had no doubt how narrator Anastasia felt about her love interest, her life, her sex life, her friends, etc. I had empathy for her. In contrast, I never quite feel what Irving’s main character, whose name I’ve forgotten, feels. His sex scenes are detailed to say the least—I’ve never read or heard anything that included so many uses of words for male and female anatomy—but, to me, not compelling. They are told with a tone of irony and detached observation. Most novels I was required to read in high school and college had that type of distance between the author’s voice and the characters. Most were written using an omniscient narrator. In that style, the narrator knows all about everything, sometimes even intruding and commenting on the plot or the characters’ choices, but stays a bit removed and above it all. Current fiction tends to set the reader right in the characters’ hearts and minds. I think this has led to associating “literature” with distance and popular fiction (which for some equals “trash”) with emotional connection. Though certainly there are literary writers, such as Dorothy Allison, whose work I find almost too hard to read due to the depth of the characters’ emotions.

Guilt/Entertainment: Many people feel guilty about enjoying reading. If a book is fun and they can’t put it down, they believe it must not have literary merit. On the other hand, if most people groan when they hear the title and say, “Ugh, yeah, I had to read that in school,” or if at the very least it takes effort and planning to get yourself to sit on the couch and open it, then a novel must be good, it must be literary. So a fast read like a Jonathan Kellerman or a Mary Higgins Clark is trash, and a novel that plods along where you don’t care one way or another about the characters must be literary. Again, I think this is a holdover from high school and college.

What the Book is About: I don’t mean the subject of the main storyline. In One Person and Fifty Shades of Grey are both about sexual awakening and experiences. But the former also explores sociological and political questions such as how the main character’s family responds to him and his orientation, what role heredity and environment may or may not play in sexuality, and how society treated and treats people who are bisexual. In contrast, for the most part, Fifty Shades focuses on the personal relationship between Anastasia and her love interest and leaves larger questions about society untouched. This is not to say that a reader couldn’t extrapolate from Anastasia’s experiences and feelings to a larger theme, but, to me at least, that isn’t in the text of the book. (Perhaps this is why I saw Irving’s book referred to as “literary porn,” while Fifty Shades is often called “mommy porn.”) This criteria is one that, for me, often divides what I think of as pure of-the-moment entertainment versus a book that makes me keep thinking about it long after I’ve finished. But I’ve felt this way about both books that are considered literary and those that are considered genre or mainstream fiction, such as certain Stephen King novels, my favorite being The Dead Zone.

The Education Needed to Read And Understand the Book: By education, I don’t mean level in school, but the breadth of knowledge a person needs to understand the book. I suspect this is a principal reason Shakespeare was considered entertainment for the masses when originally performed and is now considered literary. For most of us, enjoying Shakespeare’s plays takes a certain amount of knowledge of the times in which they were written and the changes in the language since then. That can be gained through reading an annotated text or joining literature classes or discussion groups, but it takes more effort than, say, a detective novel. So readers of Shakespeare and similar books may see themselves as smarter, more educated, and more like serious readers even if they only read a few books a year, while I tend to think of serious readers as those who love to read book after book after book.

The Gender of the Author and the Main Character: Look at any overall list of best literary fiction and you’ll find it dominated by men, and white men at that. This is starting to change, so now you’ll find women writers and writers of color included in literary book lists for recent years. All the same, being male helps if you want to be considered a serious author. Something else I’ve noticed is that a coming of age book about a young woman is generally considered a genre or young adult book (think Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret, or anything else by Judy Blume if you’re my age or the Hunger Games or Divergent novels), and thus, to some people, a lesser sort of book—a sentiment with which I disagree. A coming of age book about a young man, however, is often considered literary. Think about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Catcher in the Rye. There are exceptions; for instance, I found To Kill a Mockingbird on one list of literary coming of age novels (along with 9 books about boys/men). Likewise, when women write about sexual or romantic love, by and large it is considered trash—think of the view of most everyone you know about romance or “women’s” novels. When men write about sexual exploits, though, it is literary. Ask Vladimir Nabokov and John Irving.

------------------------------------------------------------------Would you like to receive Lisa M. Lilly's e-newsletter with M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) book and film reviews? Your email address will not be shared or sold.Join here. ------------------------------------------------------------------

The Track Record of the Author: This is the one that probably applies most directly to the two books I’ve been comparing. Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction (fiction where the writer adopts characters of an already existing book, movie, or television show) based on the Twilight series. The author was an unknown in the fiction world. Only after she self-published it as an e-book and it became wildly popular did a traditional publisher take it on. John Irving, in contrast, had twelve novels published before In One Person, for the most part to critical acclaim. Based on his pedigree, I assumed when reading In One Person that Irving deliberately chose for stylistic reasons to have the narrator retell various anecdotes and refer to his uncle and other characters a gazillion times by nicknames such as “The Racket Man.” (Or “racquetman,” I’m not sure, as I listened rather than read and didn’t care enough about any of the characters to track it down or figure it out from context.) On the other hand, knowing the history of Fifty Shades of Grey, I assumed that when the entire contract between the narrator and her love interest was included word-for-word more than once, it was because the story initially had been told in serial fashion, so the author had repeated it for readers who hadn’t started at the beginning, then not thought to edit it out when transforming the work into one complete novel. Similarly, I ascribed catch phrases that made me cringe to inexperienced writing. In short, while I didn’t like either writing style, I concluded Irving was trying to achieve an effect that just didn’t work for me, while E.L. James’ novel needed another round or two of rewriting or editing. Accurate in either case? Maybe, maybe not.

As to for my own writing, as in reading fiction, plot matters to me most, then character, then the writing style, but I strive for all three to be as strong as possible. And I don’t consider anything I read “trash,” just a book or style or subject that’s not for me. What about you? Do read—or write—anything you would call trash? If so, what does that mean to you?

----------------- Lisa M. Lilly is the author of the occult thrillers The Awakening and The Unbelievers, Books 1 and 2 in the Awakening series. A short film of the title story of her collection The Tower Formerly Known as Sears and Two Other Tales of Urban Horror was produced under the title Willis Tower. If you'd like to be notified of new releases and read reviews of M.O.S.T. (Mystery, Occult, Suspense, Thriller) books and movies click here.

Published on June 30, 2015 15:49

May 25, 2015

War, the Roads, and the Value of Life

Recently I read Unbroken for my women's book group. It made me think about my father, who is pictured below, and it seemed appropriate to write about it on Memorial Day.

WWII Naval Aviator Francis G. Lilly with his motherLike Louis Zamperini, whose life Unbroken chronicles, my dad was a WWII naval aviator. Dad tried to join the Army and was turned down because he had flat feet. He was then not only accepted by the Navy, but trained to be a pilot. He enlisted just before the Pearl Harbor attack and remained in the service six months after the war ended so he could keep flying. (He commented as an aside once that the Navy nurses really liked getting rides in the planes when he did his flights to keep certification during that time period, but I never could get much more detail about that. Perhaps because my mom was usually around when I was talking with my dad.)