Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 55

August 15, 2014

Elyana Action Figure

I’ve had limited Internet access and limited time, so I didn’t get to an update this morning. I’m having a fantastic time at GenCon and the Writer’s Symposium. The Paizo crew has always treated me wonderfully, but I had a special treat when I arrived at the booth Friday. Publisher Erik Mona handed me a MiniMates pack that features the main character from my first two Paizo Pathfinder novels, Elyana Sedrastis.

I’ve had limited Internet access and limited time, so I didn’t get to an update this morning. I’m having a fantastic time at GenCon and the Writer’s Symposium. The Paizo crew has always treated me wonderfully, but I had a special treat when I arrived at the booth Friday. Publisher Erik Mona handed me a MiniMates pack that features the main character from my first two Paizo Pathfinder novels, Elyana Sedrastis.

I’ve got to tell you — it’s pretty cool seeing an action figure based on a character that you created, and I heartily thanked Erik.

I swore to myself I’d take more pics of the convention this year, and so I have, and here are just a few, mostly from the great hall. More will come next week.

The Paizo booth just a few minutes before opening day and the loooong lines to buy all the cool stuff.

First sighting of the new D&D Player’s Handbook in the wild.

Cool stuff in the Great Hall.

A really cool home-made Rocketeer costume!

August 13, 2014

Off to GenCon

Late this morning I’m headed out on a comparatively short drive to GenCon. I’ll be there in a little under three hours, which isn’t too bad at all. I’m arriving a day early to meet up with friends and fellow writers from the Writer’s Symposium, one of GenCon’s best kept secrets. In my absence the home will be protected by a black belt, a brown belt, two dogs, and four man eating horses.

Late this morning I’m headed out on a comparatively short drive to GenCon. I’ll be there in a little under three hours, which isn’t too bad at all. I’m arriving a day early to meet up with friends and fellow writers from the Writer’s Symposium, one of GenCon’s best kept secrets. In my absence the home will be protected by a black belt, a brown belt, two dogs, and four man eating horses.

I kid — the horses aren’t actually man eaters, but everything else is true — although I think my nimble brown belt is probably more dangerous than the black belt, as her kicks have a helluva lot of power behind them. I’ve never forgotten that three teenaged girls were testing for their black belts at the same time I tested for mine. They might have looked slight in frame, but due to great flexibility and long coltish legs they were probably twice as dangerous. That sudden, precise snap at the end of the kick looked like the receiving end would be mighty painful.

2013 GenCon Writer’s Symposium attendees.

Anyway. Once at GenCon I’ll be sitting down on any number of writing and publishing panels for the next four days, trying to offer wise nuggets of advice, and I’ll frequently be at the Paizo booth in the Great Hall signing books. I’ll print the complete schedule again below. Click here to find a description of the Writer’s Symposium and further links to my adventures at last year’s convention.

I attend not just as a participant, but as a customer. I’m looking forward to seeing friends, fans, and colleagues, and to seeing all the treasures in the Great Hall. Some of those treasures I’ll just wander by and marvel over, like the furniture especially designed for gamers, and others I’ll leaf through and “remember when.” But I’m sure I’ll be making some purchases. I’m a sucker for Traveller books, even if I never actually play the game anymore, and as regular visitors know, I’ve grown quite fond of both Castles & Crusades and Savage Worlds, so I’m apt to buy a book or two at their booths. And who knows — I’ll likely stumble upon some neat thing I’ve never seen before that I’ve just got to have! I’ve even heard that Primevel Thule is going to be available. I pledged their Kickstarter last year, so I’ll definitely be lining up to pick up my copy of the book — so long as I don’t have to wait in a REALLY long line.

I’m taking my camera this year, again, and will try to remember to snap a few more pictures. We’ll see if I get my act together enough to do it.

Hope to see your there!

Howard’s GenCon Schedule

Indianapolis, IN — August 14-17, 2014

Thursday, August 14

9:00 Writer’s Craft: Writing 101. “In this introduction to writing, we cover everything from the grammar basics to punctuation. It’s a one-hour crash course that’s perfect for new writers or authors looking to brush up their skills.” Held in Room 243 with Michael Z. Williamson, Jason Schmetzer, Andrea Howe, and Moderator Elizabeth Vaughan.

1:00 – 3:00. I’ll be at the Paizo booth in the Great Hall.

3:00 Writer’s Craft: Team Dynamics. “Learn to make a group of characters more than just a bunch of people in the same room, and explore how the team is impacted by the growth of the individual characters in it.” Held in Room 245 with Erik Scott de Bie, David B. Coe, Carrie Harris and Moderator John Helfers.

6:00 Writer’s Craft: Editing Your Work. “Make your stories the very best they can be with these tips, tricks, and techniques for editing your own work.” Held in Room 245 with Geoffrey Girard, Kameron Hurley and Moderator Kelly Swails.

Friday, August 15

10:00 Editing: What is an Editor? “What is an editor? Who assigns them to your project? What do they do? And can you ignore their advice? All the secrets of editors will be revealed in this illuminating panel!” Held in Room 244 with Gabrielle Harbowy, Jerry Gordon, Erin Evans and Moderator Kerrie Hughes.

11:00 – 1:00. I’ll be at the Paizo booth in the Great Hall.

3:00 Writer’s Craft: Writing a Synopsis. “Learn what a synopsis is, what it’s for, and how to write one. We’ll also look at the different ways to write a synopsis based on your target audience.” Held in Room 243 with Greg Wilson and Moderator Marc Tassin.

7:00 Writer’s Craft: Twists Vs. Gimmicks. “Explore the difference between twists that make stories interesting and gimmicks that make readers groan. Tips and tricks for walking the thin line between interesting surprises and tired tropes.” Held in Room 245with Brian McClellan, Cassandra Rose Clarke, Greg Wilson, and Moderator Don Bingle.

Saturday, August 16

9:00 Writer’s Life: Writer’s Toolbox. “Go beyond Google Searches as we dig into the tools writers rely on to craft their stories. From tips on performing expert interviews to online resources, our panelists share their favorite tools.” Held in Room 245 with Chris Jackson, Jason Schmetzer, Sam Sykes, and Moderator Elizabeth Vaughan.

11:00 – 1:00. I’ll be at the Paizo booth in the Great Hall.

Sunday, August 17

10:00 – 12:00. I’ll be at the Paizo booth in the Great Hall.

3:00 Paizo Pathfinder Tales Seminar. Room 231.

August 11, 2014

Alchemical Storytelling

I chanced upon a show a few years ago that began with potential and then delivered on it episode after episode. I found fabulous world building and strong character arcs. I watched half hour after half hour the way I devour chapter after chapter in a great fantasy novel, poised on the edge of my seat wondering how things would resolve.

I chanced upon a show a few years ago that began with potential and then delivered on it episode after episode. I found fabulous world building and strong character arcs. I watched half hour after half hour the way I devour chapter after chapter in a great fantasy novel, poised on the edge of my seat wondering how things would resolve.

The show that so enthralled me is Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. The series is set in an alternate world in the 1900s, one very similar to our own, except that alchemy is real. Those talented and diligent enough can transform matter from one state to another — fix a broken radio into one that works, or convert a metal bar into a sword. The story’s protagonists are a pair of young brothers of tremendous talent who used their powers to commit the ultimate alchemical taboo: they tried to bring their dead mother back to life. They paid a terrible price when the transmutation went horribly wrong, and spend much of the series trying to put things right.

As the young men search for solutions they uncover hidden layers to the way alchemy, their country, and their world, truly work. As the mysteries deepen, so do the characters and the world. I really don’t want to say much more for fear of ruining the many unfolding surprises.

Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood closely follows a recenty famous — and bestselling — manga (a graphic novel series) written and drawn by Hiromu Arakawa. In 2003, after the first third of Arakawa’s manga was published, an earlier anime was begun, also titled Fullmetal Alchemist (without brotherhood). Lacking a completed story, the earlier show’s writers made up their own conclusion, one that left threads unresolved and wrapped up others in unsatisfying ways. (Honestly, that’s being charitable — I found it deeply flawed.) If you’ve seen that, don’t confuse it withBrotherhood. One does not follow the other, although, if you find that you’ve loved Brotherhood, the first ten or twelve episodes of the original deal with parts of the opening story sequence in a little more detail. Unfortunately, they don’t fit seamlessly together, as divergent plot threads occur pretty early on — so start with Brotherhood and come back if you want to see just a little bit more of the brothers in action.

Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood closely follows a recenty famous — and bestselling — manga (a graphic novel series) written and drawn by Hiromu Arakawa. In 2003, after the first third of Arakawa’s manga was published, an earlier anime was begun, also titled Fullmetal Alchemist (without brotherhood). Lacking a completed story, the earlier show’s writers made up their own conclusion, one that left threads unresolved and wrapped up others in unsatisfying ways. (Honestly, that’s being charitable — I found it deeply flawed.) If you’ve seen that, don’t confuse it withBrotherhood. One does not follow the other, although, if you find that you’ve loved Brotherhood, the first ten or twelve episodes of the original deal with parts of the opening story sequence in a little more detail. Unfortunately, they don’t fit seamlessly together, as divergent plot threads occur pretty early on — so start with Brotherhood and come back if you want to see just a little bit more of the brothers in action.

If, like me, you’re still fairly new to anime, there are a few caveats. There are occasional odd tonal shifts. For instance, when characters feel a really strong emotion (like anger or sadness) they’re often briefly transformed into caricatures of themselves, with exaggerated features. Some of the humor doesn’t translate and comes off as a bit goofy, and characters do sometimes speak over dramatically or are too revealing of their motivations when they talk. I wasn’t sure what to make of it after the first one or two shows, but kept watching… and I was glad I did. Most of the time it works, and overall it works brilliantly. Male and female characters are given strong roles, and face difficult choices.

If, like me, you’re still fairly new to anime, there are a few caveats. There are occasional odd tonal shifts. For instance, when characters feel a really strong emotion (like anger or sadness) they’re often briefly transformed into caricatures of themselves, with exaggerated features. Some of the humor doesn’t translate and comes off as a bit goofy, and characters do sometimes speak over dramatically or are too revealing of their motivations when they talk. I wasn’t sure what to make of it after the first one or two shows, but kept watching… and I was glad I did. Most of the time it works, and overall it works brilliantly. Male and female characters are given strong roles, and face difficult choices.

What starts out seeming like a lightly interesting and slightly goofy cartoon show quickly develops into something that explores some very deep themes: honor, responsibility, sacrifice, redemption, duty to one’s country, duty to humanity, the duty of a ruler to his people, loyalty, friendship, love, death. Alphonse and Edward face temptation many times, but after their initial mistake stick always to their principles, no matter how much tougher that makes things for them. And for all that there is cartoony martial arts violence there is also death, and the deaths on the show have real and lasting impact upon the characters.

What starts out seeming like a lightly interesting and slightly goofy cartoon show quickly develops into something that explores some very deep themes: honor, responsibility, sacrifice, redemption, duty to one’s country, duty to humanity, the duty of a ruler to his people, loyalty, friendship, love, death. Alphonse and Edward face temptation many times, but after their initial mistake stick always to their principles, no matter how much tougher that makes things for them. And for all that there is cartoony martial arts violence there is also death, and the deaths on the show have real and lasting impact upon the characters.

The story is greatly aided by strong, fluid visuals, including some incredible action sequences and magical displays, and it is brought to life by the American voice actors. All are at least passable (there’s no one wooden), and many of them are good to exceptional, particularly the leads. Vic Mignogna, who voices Edward, is phenomenal, and has been recognized as such by the American Anime Awards, who presented him with an award for Best Actor in a lead role for his work as Edward Elric. (I’ve praised him before on this site for his fabulous portrayal of Captain Kirk.)

Lt. Hawkeye.

I watched the first three seasons courtesy of Netflix, found the fourth season on Hulu, and then, as the fifth season wasn’t yet on Hulu, took the extraordinary (for me) step of buying the fifth and final season to watch from disc. I just couldn’t wait to see how the plot threads and character arcs all worked out. Believe me, it was worth it. My wife and children ended up loving it just as much or even more than I did.

But that leads to a final, important point: there are some disturbing moments of violence and horror within the story, although they are not gratuitous. Those moments have lasting impact upon the characters who witness them. As I said, deaths in this show have repercussions. Children who are used only to seeing American action shows where bullets always miss and everyone is just fine in the end might be rudely shocked, and some of the images might grant nightmares. Younger children and even pre-teens probably wouldn’t be able to follow along with the complex themes and shifting loyalties, either.

If you haven’t already tried it out, I hope you’ll give it a look, and I’ll look forward to hearing your thoughts. Be sure not to read series discussions online, as many of those who’ve written about it carelessly reveal plot points and character arcs. The show is constructed well enough that you should try to experience it the way Ms. Arakawa intended. Heck, even some of the pictures on packaging reveal too much, so don’t look ahead! Let the mystery unfold.

I should add that after I posted an earlier version of this review at Black Gate in 2011 I went on an anime search for shows (not movies) that were as good. I received many recommendations from a wide variety of people whom I respect, but I am sad to report that there’s only one animated series I’ve seen that’s in a similar class, Avatar: The Last Airbender. I have a few more allegedly great anime series yet to try, but I’m growing increasingly pessimistic. But then it’s a real challenge to find storytelling this good, in any medium.

August 8, 2014

Princess Azula

Avatar: The Last Airbender is so much more than it seems to be on watching the opening episodes. On first glance it may appear to be an episodic kid’s show where one evil character will constantly chase the good characters from place to place. Don’t be deceived. The storytellers build on the premise and deliver something truly astounding. The only other anime I’ve seen that’s even remotely in its same class is Full Metal Alchemist: Brotherhood.

I can recommend The Last Airbender as both as a source for viewing pleasure and as an inspiration for fellow storytellers. If you haven’t watched it yet, get to it, and if you’re skeptical after the first few episodes, give it time. You can place your trust in these storytellers — they will come through for you.

August 6, 2014

GenCon AND More on Ki-Gor

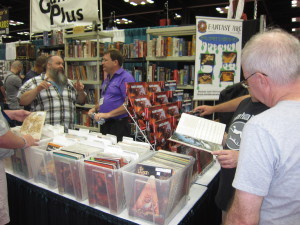

A light traffic moment in GenCon’s Hall of Treasure.

I wanted to follow up on two completely unrelated posts today.

First, I’ve mentioned that I’ll be spending a lot of time at the Paizo booth in the Great Hall at GenCon in Indianapolis next week (in addition to the hours I’ll be spending on panels during the Writer’s Symposium). As I’ve mentioned in the past, the Writer’s Symposium is chock full of good panels if you’re at all curious about the industry, or about bettering your own writing — or if you just want to find out more about your favorite writers!

Here are my hours at the Paizo Booth:

Thursday 1-3

Friday 11-1

Saturday 11-1

Sunday 10-12

You can see my full schedule over on the Appearances page, which lists not only my panel times (and the panel locations) but the topics under discussion during each panel. I hope to see folks at one place or the other, or simply as I’m wandering around taking in the sights.

Second, following up on my Ki-Gor post of a few days ago, I was contacted by Phil Lovecraft, who wondered why I almost always discussed physical books rather than e-books. I somewhat shamefacedly admitted that was because I don’t yet own an e-reader. At first that was simply because of cost, and then it was because a lot of the stuff I’m interested in (earlier fiction) wasn’t available in e-format. But now prices are lower and a lot of more obscure stuff is becoming available, cheaper, than some of it is in its original format (for instance the works of Ben Haas –aka John Benteen and Thorne Douglas — and Wade Miller, about whom I still need to write a good post). I guess that means I’ll make an e-reader purchase sooner or later.

Second, following up on my Ki-Gor post of a few days ago, I was contacted by Phil Lovecraft, who wondered why I almost always discussed physical books rather than e-books. I somewhat shamefacedly admitted that was because I don’t yet own an e-reader. At first that was simply because of cost, and then it was because a lot of the stuff I’m interested in (earlier fiction) wasn’t available in e-format. But now prices are lower and a lot of more obscure stuff is becoming available, cheaper, than some of it is in its original format (for instance the works of Ben Haas –aka John Benteen and Thorne Douglas — and Wade Miller, about whom I still need to write a good post). I guess that means I’ll make an e-reader purchase sooner or later.

I digress. Back to Ki-Gor, you can visit the comments section from my Ki-Gor post to find three good links from Phil, or, if you’ve grown curious about Ki-Gor after I discussed the series strengths and weaknesses, jump straight to this online copy of one of the best.

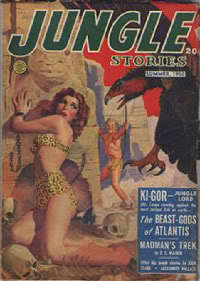

As promised in the article, it’s cliche and non-PC and entrenched in its day, yet at the same time is leavened with stirring (and purple) narrative, driving pace, evocative description, and colorblind heroes, including brave black men who are WAY cooler and more capable than you’d have thought from the time. Keeping in mind ALL the detailed caveats from the post of the other day, here, then, is one of Ki-Gor’s very best, “The Beast-Gods of Atlantis,” in two formats: flipbook, and PDF.

August 4, 2014

Strange Days

…or, possibly, strange careers. Like writing. I realized the other day that while I’ve been writing like a madman for at least twelve months, the three books I’ve been working on won’t be seen by readers for at least another twelve months.

…or, possibly, strange careers. Like writing. I realized the other day that while I’ve been writing like a madman for at least twelve months, the three books I’ve been working on won’t be seen by readers for at least another twelve months.

Any fan who’s not visiting my blog to check up on my activities will likely assume I’ve given it up or am out of ideas. And yet I’ve written two books in the last year and am nearly through with a third. After it gets a polish I’ll start work on the next one, which will mean I’ll have been working on four separate books over the course of a year. Not too shabby, really, when it took me a year and a half to write The Bones of the Old Ones. Remember that one? No? It got a starred review from Publisher’s Weekly and made the Best of 2012 Barnes and Noble fantasy releases list, and had heaps of good reviews, I swear. Alas, it doesn’t seem like anyone apart from the reviewers and some loyal fans ever picked it up, at least judging from the small number of Amazon reviews. Sniff.

With such a long time since I’ve had anything on the shelves, I’ve been scratching my head. How do I remind readers I’m still alive out here and working away? I don’t know that there are THAT many people out there waiting breathlessly for the next novel by Howard Andrew Jones, so I suppose I’ll just hope that when my newest works finally launch they’ll soar.

With such a long time since I’ve had anything on the shelves, I’ve been scratching my head. How do I remind readers I’m still alive out here and working away? I don’t know that there are THAT many people out there waiting breathlessly for the next novel by Howard Andrew Jones, so I suppose I’ll just hope that when my newest works finally launch they’ll soar.

And while I’m under this publishing delay, I’ll keep writing more and get up a stockpile of stuff so that delays become less likely. If nothing else, over the last few years I’ve figured out a lot more about how books are written (or at least how I need to write them) and how to write them swiftly. I’d like to think I’ve learned how to write better books as well, but I suppose time will tell.

One other thing I’ve figured out is that while it’s okay to sniffle a little now and then, self-pity doesn’t get you much. I wrote a book I loved that didn’t sell as well as I wanted. Okay, well, I’ll just write another, better one. Fall down ten times, get up eleven, and all that. Or as Hannibal of Carthage said, “I shall find a way, or make one.”

There’s luck involved in this business, sure, and talent, but I believe perseverance and stubbornness has a whole lot to do with succeeding in it. And I’ve got a lot of the latter two qualities, maybe because I’ve been striving most of my life to get here and its too late to turn back. Or maybe because I have lots of stories I want to tell.

August 1, 2014

The Mighty Ki-Gor, Tarzan’s Forgotten Rival

In graduate school one of my guilty pleasures was reading some pretty mindless escapist adventure. From the middle to the end of semesters things could get more than a little hectic, what with all the projects and research papers, and it was nice to be able to just pick up a story and be entertained for a while by my old friend Ki-Gor. But who’s Ki-Gor? A Tarzan clone? And how on Earth (and why?) did I get interested in reading about him?

In graduate school one of my guilty pleasures was reading some pretty mindless escapist adventure. From the middle to the end of semesters things could get more than a little hectic, what with all the projects and research papers, and it was nice to be able to just pick up a story and be entertained for a while by my old friend Ki-Gor. But who’s Ki-Gor? A Tarzan clone? And how on Earth (and why?) did I get interested in reading about him?

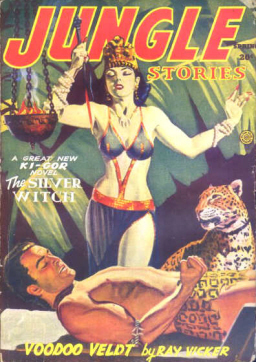

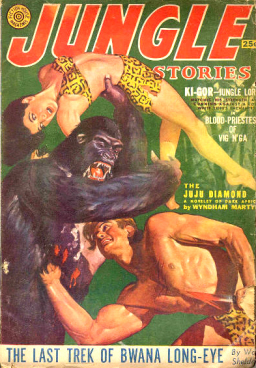

Some years back, at Pulpcon, I was wandering around the dealer room with writer John C. Hocking and sword-and-sorcery scholar Morgan Holmes. I stopped to chuckle at a ridiculous-looking pulp cover on display at one of the booths. Jungle Stories was emblazoned upon the masthead. Below, a beautiful and clearly evil dark-haired woman loomed over a bronzed jungle-man bound to an altar. Morgan said, “That’s actually a pretty good story.”

Knowing that Morgan Holmes is better read on sword-and-sorcery (and any kind of heroic fiction, really) than anyone else in existence, his comment pulled me up short. And then Hocking chimed in as well. “Some of the Ki-Gors are pretty great stuff,” he told me, then added caveats, which I’ll detail in a moment.

I took the chance and picked up that 1950s issue of Jungle Stories. I wasn’t quite sure what I’d get, but what I didn’t expect was an action-packed adventure with glowing zombie-men who disintegrated into ash when slain, or the machinations of an ageless sorceress intent on… well, I don’t remember what she was intent on, really, but she wanted to conquer something, and she fell for Ki-Gor, hard, as scheming villainesses do. It was ridiculous and over-the-top and certainly not politically correct, but at the same time it was thrilling and firing on all cylinders. I had the inescapable sense while reading it that the writer had said to himself, “Well, if I’m being hired to write a cliched jungle adventure I’m going to make it the best cliched jungle adventure I possibly can.” And so he had. It was a blast, cliches and all.

I had stumbled outside of my genre comfort zone and discovered something fascinating. I had to find more Ki-Gor. Who was he, and what about these Jungle Stories? Were they all this much fun, with so many fantasy elements?

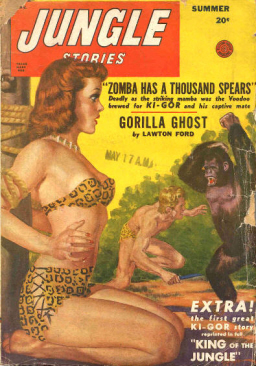

It goes without saying that without Tarzan, there would be no Ki-Gor. The blond-haired jungle-man was crafted to meet the tastes of a public with an insatiable appetite for the adventures of Burroughs’s hero. Ki-Gor was not the first Tarzan clone, but he seems to have sustained the longest known run of any of Burroughs’s imitators. This was partly because there was money behind Jungle Stories, the pulp that printed the adventures of Ki-Gor for close to 17 years, from 1938 to 1954. For most of that run, readers could head to their local newsstand once every quarter and find the mighty Ki-Gor emblazoned across the cover wrestling a giant snake or a lion or an angry native, while his gorgeous “flame-haired” wife posed nearby in a two-piece leopard-skin bikini (frequently bound and sometimes gagged, which has made the covers popular amongst another set of collectors).

It goes without saying that without Tarzan, there would be no Ki-Gor. The blond-haired jungle-man was crafted to meet the tastes of a public with an insatiable appetite for the adventures of Burroughs’s hero. Ki-Gor was not the first Tarzan clone, but he seems to have sustained the longest known run of any of Burroughs’s imitators. This was partly because there was money behind Jungle Stories, the pulp that printed the adventures of Ki-Gor for close to 17 years, from 1938 to 1954. For most of that run, readers could head to their local newsstand once every quarter and find the mighty Ki-Gor emblazoned across the cover wrestling a giant snake or a lion or an angry native, while his gorgeous “flame-haired” wife posed nearby in a two-piece leopard-skin bikini (frequently bound and sometimes gagged, which has made the covers popular amongst another set of collectors).

Each issue of Jungle Stories opened with a Ki-Gor “novel” (meaning a piece that came in between 20 and 40 thousand words) followed by shorter stories of unrelated characters. Ki-Gor was the magazine’s real draw, and his escapades backed up the promise of the covers, for there were dangers aplenty to be overcome by the jungle lord. The prose was purple, the action relentless, and cliffhangers closed almost every section.

While on the surface Ki-Gor sounds very much like any other Tarzan-inspired pastiche, he often rose above his humble origins. Written as he was by a house name, the true authors of Ki-Gor’s chronicles are little known, which is why we can’t be sure why a number of them are so much better than they really deserve to be. Close to a third of Ki-Gor’s adventures stand head-and-shoulders above the rest. The prose is tighter, the characters deeper, the setting more vivid (and frequently more bizarre) than almost anything Burroughs ever cooked up for Tarzan. The best of them crackle with the kind of energy visitors to the old pulp mags expect and almost never find. The worst though, ye Gods. They can be stinkers.

Under different hands, all the characters fare differently, but none so much as Tembu George, Ki-Gor’s friend and chief of a tribe of Massai warriors. In the bad Ki-Gors he’s a humble former southerner with a step-and-fetch accent, eager to please. In the good Ki-Gors, Tembu George is noble, brave, resourceful, and simply way, WAY cooler than you’d think any black man would be in a 1950s magazine aimed at white men (he’s actually cooler than ANY black hero I’m familiar with until we get much closer to the modern era). Ki-Gor is color-blind and willingly risks life and limb for Tembu George and his pygmy friend, N’Geeso, more times than you can count, and those two always reciprocate, for the three view each other as brothers. In that way, if none other, Ki-Gor was ahead of its time.

Approximately 59 Ki-Gor novellas were published during the run of Jungle Stories. The number is inexact because later in its run Jungle Stories sometimes re-used covers (upon which a novella title was already emblazoned) and printed a new story using the same name. Sometimes Jungle Stories reprinted the original story, and sometimes it reprinted a different story while reprinting an unrelated cover. The circumstances have led to some confusion about the precise number of stories, and which story has which title. Despite that, it’s possible to safely make several generalizations.

Approximately 59 Ki-Gor novellas were published during the run of Jungle Stories. The number is inexact because later in its run Jungle Stories sometimes re-used covers (upon which a novella title was already emblazoned) and printed a new story using the same name. Sometimes Jungle Stories reprinted the original story, and sometimes it reprinted a different story while reprinting an unrelated cover. The circumstances have led to some confusion about the precise number of stories, and which story has which title. Despite that, it’s possible to safely make several generalizations.

The first three or four years of Ki-Gor, from 1938 to 1941, sound the most dated. Ki-Gor himself isn’t especially clever and the natives are embarrassingly non-pc. After the 13th issue, Ki-Gor began to take on an easy nobility of spirit and his loyal native friends started to demonstrate both independence of thought and real capability. By Ki-Gor’s sixth year of existence, and for many years thereafter, this portrayal became more the norm than the exception, until Jungle Stories lost steam and direction. Lesser Ki-Gors dropped into the mix more and more frequently, and Ki-Gor’s final years were less inventive — although the series ended on a high note.

In all, there are some 15 to 20 good Ki-Gors. Not good in a Proust sense, or good in a unique Tolkien or Jack Vance world-building sense, but good as grand pulp adventures. In them, one can find lost civilizations, evil queens, ancient temples and curses, noble friends, evil schemes, monsters from the dawn of time, mad scientists, telepathy, battles against overwhelming forces, supernatural menace, and above all action with a capital A. Hocking described the good ones as sounding a little like Robert E. Howard or Mickey Spillane writing a Tarzan story. They tend to recycle themes — Helene captured, a lost ancient civilization still existing in the jungle, Ki-Gor framed — but when they’re not read back to back, they’re loopy fun. THIS time, Ki-Gor must save his wife and native women from marauding cave men freed from an ancient valley! THIS time, Ki-Gor must stop a horde of vampiric flying squirrels, commanded by a beautiful telepathic Indian (no, I’m not kidding).

The “good” ones are enough fun that people like Hocking and Andy Beau and I slogged our way through a mountain of bad ones looking for more gold.

You don’t need to think a whole lot about these tales, which made them great for reading in the middle of my grad school studies. If a few days had gone by since I’d had time to read and I’d forgotten what page I was on, it didn’t matter. I’d discover Ki-Gor in the middle of a fight with a crocodile, or Tembu George in furious combat with his shovel-bladed Massai spear, and I’d sit back and enjoy.

Even a list of Ki-Gor titles is outrageous fun, but there’s nothing quite like the delicious purple of the blurbs that introduce each story. Here are a couple of samples. First, from “The Monkey Men of Loba-Gola” (which, incidentally, had NO monkey-men in it whatsoever):

Even a list of Ki-Gor titles is outrageous fun, but there’s nothing quite like the delicious purple of the blurbs that introduce each story. Here are a couple of samples. First, from “The Monkey Men of Loba-Gola” (which, incidentally, had NO monkey-men in it whatsoever):

Ki-Gor, White Lord of the Jungle, tracked a treachery spoor to the Forest of Treasure, challenging lovely, mad Zoanna and her evil Master. But a devil’s trap was waiting. Ki-Gor faced a battle no man might win… against Nihilla Ati, the Invisible Vampire of Death!

And how about this one, from “The Golden Claws of Raa:”

Sam Slater, cobra-eyed merchant of warrior-flesh; Mog, the gorilla with human blood on his dagger-like teeth– and Raa, white queen of the ape legions… these were Ki-Gor’s enemies in a battle that only the voodoo of Fate could decide!

They don’t write ‘em like that anymore.

Anyway, here’s my list of the absolute best Ki-Gor stories, in no particular order:

The Silver Witch

The Beast-Gods of Atlantis

The Sword of Sheba

Lost Priestess of the Nile

The Monkey-Men of Loba-Gola

Huntress of the Hell-Pack

The Monsters of Voodoo Isle (not to be confused with another story, Monster of Voodoo Isle, which is NOT good)

The Golden Claws of Raa

Slave Brides for the Dawn-Men

Tigress of T’Wanbi

Blood Priestess of Vig N’Ga

Flame Priestess of Carthage

Warrior-Queen of Attila’s Lost Legion

Death Seeks for Congo Treasure

Stalkers of the Dawn-World

White Cannibal

Eyrie of the Golden Goddess

The Golden Beast of Zuli Maen

When I published the original version of this article at Black Gate, John Hocking added some comments that are worth reprinting. He wrote:

While the worst Ki-Gors are poor enough to be painful to read, the best ones are so good as to make wading through the bad ones worthwhile.

What the good ones have going for them is a little hard to explain to someone who isn’t a pulp fan. They aren’t classy or clever, and they are emphatically not original.

At their pinnacle what they have is a blazing enthusiasm for formula so intense that you could be forgiven for imagining the unknown author leaping up wild-eyed from his smoking typewriter, flailing his arms and leaping around his garrett in a frenzy of unleashed prose composition.

Jungle Stories collectors have generally agreed that “Stalkers of the Dawn World” is the best Ki-Gor novel, and although there are others I like as much, this may be the best exam ple of what I’m trying to get at here.

ple of what I’m trying to get at here.

“Stalkers of the Dawn World” is your basic “Jungle Man Rescues Lost Safari in a Valley of Dinosaurs” story. You could probably parse out the whole plot in a few moments even if your entire experience with jungle pulp storytelling was drawn from watching a couple Tarzan movies. Doesn’t matter.

The novel is written in a virtual typhoon of the most outrageously purple prose. Simple descriptions of the jungle attain ecstatic heights while actual scenes of action (including the inevitable climactic showdown between Ki-Gor and a T. Rex) go so far over the top as to qualify as some kind of controlled substance in prose form.

Obviously, this is the kind of thing that people who like that kind of thing are really going to like. A real high point for latter day pulp sensationalism.

In short, the good Ki-Gor’s actually sound like what you think outrageous pulp fiction really should have been like (and almost never was, in truth, because that kind of pacing and action writing is hard to pull off). They’re surprisingly fun. I enjoyed the good ones enough that I actually kept hold of them, thinking I might re-read them some day.

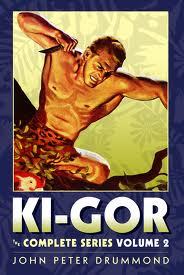

You’ll probably have an easier time finding Ki-Gor than I did and won’t have to haunt pulp magazine conventions to do so, providing you’re patient for just a little longer. There are a series of reprints courtesy of High Adventure, and, for the completists, Altus Press is compiling the entire run. They’re currently up to volume 2, and I understand that other volumes are nearly ready for print. While Volume 3 ought to be the start of the ones I find most enjoyable, it must be said that some readers seem to enjoy them right from the beginning.

July 30, 2014

Pulp Swashbucklers

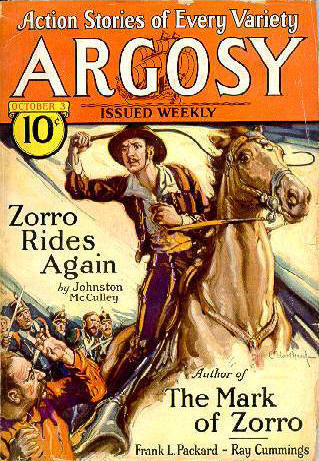

The pulp era began around the turn of the 20th century, in the days before radio and television. Magazines on all sorts of diverting topics were found on the newstands, printed on cheap, pulpy paper, hence the term “pulps.” There was something aimed at almost every reader, rather like all the television shows on cable channels today. And like television today, at least 90% of it was bad. That’s why “pulp fiction” has certain connotations-—cheap, sensationalist, and over-the-top being among them — not to mention “dated” and frequently sexist and politically incorrect. But not everything from this time period should be dismissed casually — there are treasures there, hidden among all those decades of magazines. The trick is knowing how to find the good stuff, and where to look, and today I thought I’d do my best to guide you to it.

The pulp era began around the turn of the 20th century, in the days before radio and television. Magazines on all sorts of diverting topics were found on the newstands, printed on cheap, pulpy paper, hence the term “pulps.” There was something aimed at almost every reader, rather like all the television shows on cable channels today. And like television today, at least 90% of it was bad. That’s why “pulp fiction” has certain connotations-—cheap, sensationalist, and over-the-top being among them — not to mention “dated” and frequently sexist and politically incorrect. But not everything from this time period should be dismissed casually — there are treasures there, hidden among all those decades of magazines. The trick is knowing how to find the good stuff, and where to look, and today I thought I’d do my best to guide you to it.

The pulp historical fiction of the early twentieth century (circa 1915-1940) has many of the same elements of good fantasy fiction. In place of the imaginary land is a distant era that, in the hands of the better writers, sparkles with more power than many an invented setting. There are heroes who must live by their wit and weapon skills in deadly borderlands, beset by schemers and intriguers. There is treasure to be found, and ancient secrets, and lovely women: some are old-fashioned damsels in distress, but others are keen-eyed adventurers and daring women ahead of their time. There are loyal comrades, implacable foes, powerful but foolish kings, secret societies, fabulous kingdoms, and those who pass themselves off as wizards and miracle workers. In short, if you read the sword and sorcery writers and the pulp historical fiction writers, the lineage is obvious–their stories are fashioned with the same spirit, from love of the same plot elements.

Historical fiction wasn’t the mainstay of the pulps–for the most part westerns and detective fiction were–but many an author wrote “costume pieces.”

The pulps saw the engaging though repetitious exploits of Zorro, and printed the adventures of Sabatini’s Captain Blood. Many today may not know that so famous a character as Horatio Hornblower first made his appearance in the pulp magazines.

But there are other authors, popular in their time, now nearly forgotten. There was H. Bedford-Jones, that most prolific of pulp authors (said to write a million words a year) who could be relied upon for tales of the high seas and cavaliers and Dumas-like action. (He even wrote an authorized Three Musketeers sequel!)

Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur and Farnham Bishop, writing together or separately, could be counted on for exciting tales of clashing arms and mayhem set in the distant past. Their style is sometimes slow, weighted with the pacing of the nineteenth century, yet they should not be too easily disregarded; sometimes their work springs with amazing vigor. One of the best by either man is a neglected gem of Viking adventure, originally serialized in Argosy beginning in November of 1928. Sadly, it has never seen reprint, although Black Dog Books has it on the docket. Here’s a brief look at He Rules Who Can, a novel by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur:

Suddenly Cyra shrieked. Wheeling, tugging at his ax, Harald felt her snatched from him. Even as he got his weapon clear, a knife smashed against the mail above his ribs.

Cyra was struggling in the grasp of two men. The crowds about them had vanished as if by magic at the first outcry, leaving the two surrounded by cloaked figures. Whirling his ax, Harald leaped for the two who held the girl. Instantly four men flung themselves in his way, short swords out-thrust.

Arthur D. Howden Smith crafted many a bold tale, among them the saga of the Viking Swain, and the story of Gray Maiden.

Gray Maiden was a sword first forged for a Pharaoh. In each story the blade is wielded by a different warrior, down through history. The sword is sometimes lost or entombed with its wielder, but always it is unearthed to wreak more mischief. It is a supremely sharp blade with supernatural powers—no man who bares her meets his death by sword, though they often perish in other ways.

The Gray Maiden story cycle veers widely in quality. Some portions are full of monotonous talking heads, whereas some are truly outstanding–“Thord’s Wooing” [1927] is an excellent Viking tale. A scene late in the story in the midst of a duel provides some sense of its flavor. Bjarni, mortally wounded, seeks to take the life of Thord’s mother, Elin.

“Your doing, witch,” He gasped. “Come with me!”

And he hurled his sword straight at her breast. It turned once in the air, hilt over point, a flash of light in the dimness, sped by the last strength of his body even as he collapsed in death. But Grey Maiden flew faster. Thord cast the long blade like an axe, and once more it parried Bjarni’s blow. The two swords clattered at Elin’s feet.

And you need not think that the pulps were the exclusive province of male writers, even if they were the dominant presence. I’m sure most visitors to this site know that later pulp writers like Leigh Brackett and C.L. Moore were women (…and outside the scope of this historical article, as they were writing space opera/sword-and-planet). But how many of you have read anything by Marion Polk Angellotti, who wrote a series of swashbucklers based on the exploits of a real mercenary company of the 14th century, led by the astonishing Sir John Hawkwood? Are you familiar with G.G. Pendarves, who wrote adventures set in the middle-east for both Weird Tales and Magic Carpet magazine?

And you need not think that the pulps were the exclusive province of male writers, even if they were the dominant presence. I’m sure most visitors to this site know that later pulp writers like Leigh Brackett and C.L. Moore were women (…and outside the scope of this historical article, as they were writing space opera/sword-and-planet). But how many of you have read anything by Marion Polk Angellotti, who wrote a series of swashbucklers based on the exploits of a real mercenary company of the 14th century, led by the astonishing Sir John Hawkwood? Are you familiar with G.G. Pendarves, who wrote adventures set in the middle-east for both Weird Tales and Magic Carpet magazine?

There are other fine authors and other fine tales, but two giants stride out of this field, authors famed for both quality and quantity. Both of them influenced Robert E. Howard, the father of modern sword-and-sorcery. They were Talbot Mundy and Harold Lamb.

Mundy’s real name was William Lancaster Gribbon, and before he took up writing he’d knocked about India and East Africa and Germany and nearly gotten himself killed several times over. It was while recovering in the hospital after getting blackjacked that he took up writing.

Talbot Mundy is best known for two series characters, James Grim, or Jim Grim, an American adventurer working for the British Secret Service, and Tros of Samothrace, but he wrote other tales besides

It is Tros who concerns us here. This long cycle of stories was published for the most part as a series of novellas in the pages of Adventure magazine (a novel near the end of the cycle appeared in book form). And if any fiction decries its “pulp” reputation, it is Mundy’s Tros of Samothrace. Mundy was a skilled student of human nature with philosophical leanings. His characters are rich, complex, and well drawn. His plots are hinged upon the actions taken by his heroes and villains. Sometimes the stories unfold slowly, because they are dependent upon intrigue, politics, and dialogue, but at the appropriate moments they explode with action. They are not “talky,” however–once you are involved with the characters you linger over every word.

Above all, Mundy was a careful craftsman. Consider the somber tone of the following scene from Tros of Samothrace, hardly expected of a typically garish pulp writer:

He went below, into the cabin where his father’s body lay, with Caesar’s scarlet cloak spread over it. And for a while he stood steadying himself with one hand on an overhead beam, watching the old man’s face, that was as calm as if Caesar’s tortures had never racked the seventy-year-old limbs, the firm, proud lip showing plainly through the white beard, the eyes closed as in sleep, the aristocratic hands folded on the breast.

It was dark in there and easy to imagine things. The body moved a trifle in time to the ship’s swaying.

Tros is a skilled sailor and minor initiate into an ancient and widespread mystical society, which Mundy renders entirely believable. His greatest desire is to build the ship of his dreams and sail around the world (for his people know the Earth is round) but before he can do either he runs afoul of Caesar’s ambitions. Caesar is one of Mundy’s triumphs—a rascal genius who only fails because his ego eventually grows too large. His character is depicted brilliantly.

Tros does eventually build his ship, ends up allied with Cleopatra and even, near the end, aids his old enemy Caesar. He never does manage to sail around the world, though Mundy fully planned to write that story, because his creator died of diabetes before pen went to paper. Fortunately the series ends on a completed note, with all of the hero’s Mediterranean adventures resolved.

the world, though Mundy fully planned to write that story, because his creator died of diabetes before pen went to paper. Fortunately the series ends on a completed note, with all of the hero’s Mediterranean adventures resolved.

Harold Lamb was a quiet man who was fascinated with chronicles of eastern history at an early age. Later he would create the epic Durandal trilogy, amongst other thrilling Crusader novels; later he would become a renowned historian and wealthy screenwriter, penning more than thirty movies for Cecil B. DeMille. First, though, he created a cycle of remarkable historical fiction stories set in locations as fabulous and unfamiliar to most readers as Burroughs’ Mars.

Where many adventure tales are predictable from the first word, Lamb’s plots were full of unexpected twists. He wrote convincingly of faraway lands and dealt fairly with their inhabitants, relating without bias the viewpoints of Mongols, Moslems, and Hindus. His stories are rarely profound psychological drama, but Lamb nonetheless breathed humanity into his characters, endowing them with realistic hopes and fears. Unlike almost all of his predecessors and many of his contemporaries, the pacing of most of his historicals still feels modern–he never stopped for slow exposition. His plots thunder forward as though he envisioned each one for cinema the moment he slid paper into the typewriter.

The most enduring and complex of all Lamb’s heroes was his first, Khlit the Cossack. Before Stormbringer keened in Elric’s hand, before the Gray Mouser prowled Lankhmar’s foggy streets—before even Conan trod jeweled thrones under his sandaled feet, Khlit the Cossack rode the steppe. He is the forgotten grandfather of all series sword-and-sorcery characters.

The Cossack is already old when his saga begins, late in the 16th century in the grasslands of central Asia. He is an expert horseman and swordsman, unlettered and only a step removed from barbarism, but wise in the ways of war and men. Gruff and taciturn, Khlit is a firm believer in justice and devout in his faith, though not given to prayer or religious musings. He is the friend and protector of many women, but leaves romance to his sidekicks and allies.

The stories swim in action, treachery — and places best unglimpsed by mortal men. Consider the following scene, from the novella “The Mighty Manslayer.” [1918]

The stories swim in action, treachery — and places best unglimpsed by mortal men. Consider the following scene, from the novella “The Mighty Manslayer.” [1918]

Mir Turek caught his arm and pointed to the further side.

“The Bearers of Wealth!” he screamed. “See, the Bearers of Wealth, and their burden. The Tomb of Genghis Khan. We have found the tomb of Genghis Khan!”

The shout echoed wildly up the cavern, and Khlit thought that he heard a rumbling in the depths of the cavern in answer. He looked where Mir Turek pointed. At first he saw only the veil of smoke. Then he made out a plateau of rock jutting out from the further side. On this plateau, abreast of them, and at the other end of the rock bridge gigantic shapes loomed through the vapor. Twin forms of mammoth size reared themselves, and Khlit thought that they moved, with the movement of the vapor. These forms were not men but beasts that stood side by side. Between them they supported a square object which hung as if suspended in the air.

Throughout the seventeen part series Khlit yearns for far horizons and strange new sights. He rides alone for a time before rising to lead a Tatar tribe for five tales, then later joins forces with the heroic Afghan swordsman and Moslem, Abdul Dost. Always Khlit bears his famed curved saber, gilt with the writing of an unknown tongue. It is a deadly blade with its own secret history, disclosed as the series progresses.

The Khlit saga is a remarkable tour de force, and any reader who has loved the works of Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber and those who followed them will embrace the stories of the wily old Cossack—and other Lamb stories besides.

Speaking of Robert E. Howard, some of his very best work are his historicals. Given his druthers, that’s what he would have been writing, but he never did crack Adventure or Argosy with his historical fiction. As a result, he didn’t write that much, but most of what he did draft was penned at the very top of his game.

Finding the Fiction

When I began my exploration of pulp magazine fiction I assumed that all the best work had already been collected and reprinted and that mostly dross remained. I had also assumed that finding the stories located in pulps would be a simple matter-—that probably, as with National Geographic, the old issues would be available on collections of CD-ROMs.

When I began my exploration of pulp magazine fiction I assumed that all the best work had already been collected and reprinted and that mostly dross remained. I had also assumed that finding the stories located in pulps would be a simple matter-—that probably, as with National Geographic, the old issues would be available on collections of CD-ROMs.

I could not have been more wrong. Few of the pulps are indexed at all. Even pulp magazines like the influential Weird Tales and Adventure, once hailed by Newsweek as the dean of pulp magazines, are un-indexed in that sacred cow, the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature. Naturally this makes finding specific stories or magazine issues quite challenging. There exist only a few indexes to a tiny number of pulp magazines, and only because of the efforts of a few dedicated collectors. A handful of libraries and universities are amassing pulp magazine collections, but the pulps are aging and crumbling away.

If you’re looking for analysis or discussion of this fiction, you can turn to the sixth volume of Robert Sampson’s history of pulp characters, Yesterdays Faces: Violent Lives. Sampson discusses Mundy, Lamb, and others at length. Robert Kenneth Jones’ Lure of Adventure discusses historical fiction from that famous magazine.

If you’re looking for analysis or discussion of this fiction, you can turn to the sixth volume of Robert Sampson’s history of pulp characters, Yesterdays Faces: Violent Lives. Sampson discusses Mundy, Lamb, and others at length. Robert Kenneth Jones’ Lure of Adventure discusses historical fiction from that famous magazine.

If it’s the fiction itself you’re after, you’re in much better shape than you were ten years ago when I wrote my first draft of this article. For instance, here at last are ALL of the Gray Maiden stories, collected in a single volume. No longer do you need to haunt used book search services to find a selection of the tales. Howden-Smith’s multi-part Swain’s Saga, alas, still remains uncollected in its entirety.

Tros of Samothrace is now available in several formats through several companies. A quick search on Amazon turned all of these up.

And of course nearly all of Harold Lamb’s best swashbucklers have been assembled through the University of Nebraska Press’ Bison Books imprint, scanned, compiled, and edited by yours truly. Here’s a link.

And of course nearly all of Harold Lamb’s best swashbucklers have been assembled through the University of Nebraska Press’ Bison Books imprint, scanned, compiled, and edited by yours truly. Here’s a link.

As for the more familiar authors, most libraries still have copies of at least some portions of C.S. Forrester’s Hornblower series and are likely to have a few Rafael Sabatini books on their shelves.

Until recently the original Zorro has been hard to find. All of the stories have recently been collected by Pulp Adventures. You can find the first through Amazon, and more may already be in print. Look for Zorro : The Masters Edition Vol. One.

But there are even more riches out there. Those curious about H. Bedford-Jones, Arthur D. Howden Smith, or others need look no further than Black Dog Books or Wildside Press. For instance, Wildside is offering “megapacks” of various authors, or even subjects (like pirates) for absurdly low prices. So long as you have an e-book reader, you may be in pulp heaven. I’ve personally found H. Bedford-Jones always a little hit and miss, but at .99 cents it’s a heckuva chance to try him out, and a good chance to get the hits and not mind the misses.

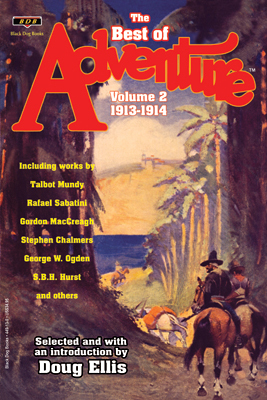

Bolstered as it is by multiple pulp scholars (among them owner Tom Roberts and frequent co-editor Doug Ellis) Black Dog Books has a deserved reputation for quality. For starters, Ellis is masterminding a “Best of” collection of Adventure magazine. So far, two volumes are available, but he recently wrote me that the next two are just about ready for press. But that’s not all — Black Dog Books is also reprinting Bedford-Jones, Bishop & Brodeur, and even more obscure historical writers — and “obscure” in this instance doesn’t mean bad. If this stuff is your cup of tea, I strongly suggest you wander through their fiction line. Make sure you look at their “Coming Soon” and “Also in Production” sections, where you’ll find even more great looking stuff, including the aforementioned novel by Bishop & Brodeur, He Rules Who Can. And Black Dog has collected all Angelloti’s tales of Sir John Hawkwood, as well all of G.G. Pendarves’ stories!

Bolstered as it is by multiple pulp scholars (among them owner Tom Roberts and frequent co-editor Doug Ellis) Black Dog Books has a deserved reputation for quality. For starters, Ellis is masterminding a “Best of” collection of Adventure magazine. So far, two volumes are available, but he recently wrote me that the next two are just about ready for press. But that’s not all — Black Dog Books is also reprinting Bedford-Jones, Bishop & Brodeur, and even more obscure historical writers — and “obscure” in this instance doesn’t mean bad. If this stuff is your cup of tea, I strongly suggest you wander through their fiction line. Make sure you look at their “Coming Soon” and “Also in Production” sections, where you’ll find even more great looking stuff, including the aforementioned novel by Bishop & Brodeur, He Rules Who Can. And Black Dog has collected all Angelloti’s tales of Sir John Hawkwood, as well all of G.G. Pendarves’ stories!

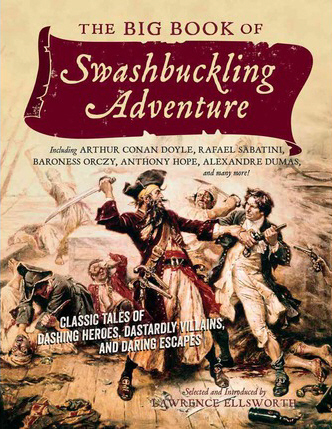

If you’re looking for a sampler of this sort of thing– perhaps a very large one — you’ll be in good hands with Lawrence Ellsworth’s Big Book of Swashbucklers, described in detail over at Black Gate.

I’ve mentioned both Wildside and Black Dog Books, and I’d be remiss not to mention Altus Press as well. Although they primarily focus on mystery and adventure (and are doing a sterling job reprinting lost noir writer Frederick Nebel), a quick look through the Altus catalog will show you a handful of swashbucklers, including the complete run of Theodore Roscoe’s French Foreign Legion stories.

I’ve mentioned both Wildside and Black Dog Books, and I’d be remiss not to mention Altus Press as well. Although they primarily focus on mystery and adventure (and are doing a sterling job reprinting lost noir writer Frederick Nebel), a quick look through the Altus catalog will show you a handful of swashbucklers, including the complete run of Theodore Roscoe’s French Foreign Legion stories.

Lastly, it’s probably no secret to regular visitors that I got to pen the afterword to the Del Rey Robert E. Howard Collection, Sword Woman, available now through Del Rey (and my pal Scott Oden got to write the introduction!).

Probably I’ve left off some other publishers and some other works, but hopefully I’ve given you a good starting point for exploration, or, if you’re already into this sort of thing, expanded your horizons. If you hear of any other publishers or pulp historical writers that need mention, don’t hesitate to write me. I can add them in to this very article, or cover them separately later.

July 28, 2014

The Great Brackett

The 4th and final Brackett collection from Haffner Press.

Only a few generations ago planetary adventure fiction had a few givens. First, it usually took place in our own solar system. Second, our own solar system was stuffed with inhabitable planets. Everyone knew that Mercury baked on one side and froze on the other, but a narrow twilight band existed between the two extremes where life might thrive. Venus was hot and swampy and crawling with dinosaurs, like prehistoric Earth had been, and Mars was a faded and dying world kept alive by the extensive canals that brought water down from the ice caps.

To enjoy Leigh Brackett, you have to get over the fact that none of this is true – which really shouldn’t be hard if you enjoy reading about vampires, telepaths, and dragons, but hey, there you go. Yeah, Mars doesn’t have a breathable atmosphere, or canals, or ancient races. If you don’t read Brackett because you can’t get past that, you’re a fuddy duddy and probably don’t like ice cream.

A few of Brackett’s finest stories were set on Venus, but it was Mars that she made her own, with vivid, crackling prose.

Here. Try this, the opening of one of her best, “The Last Days of Shandakor.” You can find it in two of the three books featured as illustrations in this article, Shannach — the Last: Farwell to Mars, and Sea-Kings of Mars and Otherworldly Stories.

Anyway. On to Brackett.

He came alone into the wineshop, wrapped in a dark red cloak, with the cowl drawn over his head. He stood for a moment by the doorway and one of the slim dark predatory women who live in those places went to him, with a silvery chiming from the little bells that were almost all she wore.

I saw her smile up at him. And then, suddenly, the smile became fixed and something happened to her eyes. She was no longer looking at the cloaked man but through him. In the oddest fashion — it was as though he had become invisible.

Many (but not all) of Brackett’s best, in one volume.

She went by him. Whether she passed some word along or not I couldn’t tell but an empty space widened around the stranger. And no one looked at him. They did not avoid looking at him. They simply refused to see him.

He began to walk slowly across the crowded room. He was very tall and he moved with a fluid, powerful grace that was beautiful to watch. People drifted out of his way, not seeming to, but doing it. The air was thick with nameless smells, shrill with the laughter of women.

Two tall barbarians, far gone in wine, were carrying on some intertribal feud and the yelling crowd had made room for them to fight. There was a silver pipe and a drum and a double-banked harp making old wild music. Lithe brown bodies leaped and whirled through the laughter and the shouting and the smoke.

The stranger walked through all this, alone, untouched, unseen. He passed close to where I sat. Perhaps because I, of all the people in that place, not only saw him but stared at him, he gave me a glance of black eyes from under the shadow of his cowl — eyes like brown coals, bright with suffering and rage.

I caught only a glimpse of his muffled face. The merest glimpse — but that was enough. Why did he have to show his face to me in that wineshop in Barrakesh?

He passed on. There was no space in the shadowy corner where he went but space was made, a circle of it, a moat between the stranger and the crowd. He sat down. I saw him lay a coin on the outer edge of the table. Presently a serving wench came up, picked up the coin and set down a cup of wine. But it was as if she waited on an empty table.

I turned to Kardak, my head drover, a Shunni with massive shoulders and uncut hair braided in an intricate tribal knot. “What’s that all about?” I asked.

Paizo’s Planet Stories imprint has reprinted a number of Brackett’s best short novels, including my very favorite, The Sword of Rhiannon.

Kardak shrugged. “Who knows.” He started to rise. “Come, JonRoss. It is time we got back to the serai.”

“We’re not leaving for hours yet. And don’t lie to me, I’ve been on Mars a long time. What is that man? Where does he come from?”

Barrakesh is the gateway between north and south. Long ago, when there were oceans in equatorial and southern Mars, when Valkis and Jekkara were proud seats of empire and not thieves’ dens, here on the edge of the northern Drylands the great caravans had come and gone to Barrakesh for a thousand thousand years. It is a place of strangers.

In the time-eaten streets of rock you see tall Kesh hillmen, nomads from the high plains of Upper Shun, lean dark men from the south who barter away the loot of forgotten tombs and temples, cosmopolitan sophisticates up from Kahora and the trade cities, where there are spaceports and all the appurtenances of modern civilization.

The red-cloaked stranger was none of these.

Now it’s possible that you’re a perfectly fine human being if you didn’t find that stirring, but my guess is that if it didn’t interest you at least a little to find out who that stranger was, you’re no fan of adventure fiction. Leigh Bracket was, simply, a master writer. Find her work, read it, and get swept away.

An earlier version of this article was posted at Black Gate in 2012.

July 22, 2014

Confessions of a Guilty Reviewer

Howard’s Review Rooster of Doom.

I used to write occasional reviews for Tangent Online, and once I wrote one that I still regret. I’ve rarely found a slice-of-life story or flash fiction that I enjoyed, so I probably had no business evaluating a piece of short fiction that was both. Yet I read it and I slammed it. Not because it was bad flash fiction, or because it was a bad slice-of-life story (I had no kind of qualifications for adequately judging either) but because I didn’t like flash fiction or slice-of-life stories. It was the epitome of ill-informed reviewing, where the writer is arrogant enough to know better than fans of an entire genre. Or two.

I didn’t understand my mistake for a while and when I met the author of the story at a convention years later he was kind enough not to mention my idiocy, or, more likely, hadn’t remembered the name of the idiot who’d written the review.

You’d think that my epiphany about having written such a bad review would have arrived when I started to get my own fiction published more regularly, but it actually hit me faster, probably because it took a loooong time for my fiction to get published regularly.

I began to evaluate game products for Black Gate and it finally dawned on me that I had to consider both a work’s intended function and its intended audience. For instance, if I was looking at a role-playing product, I couldn’t evaluate a retro dungeon crawl by the same standards I looked at a modern story-based adventure with plot arcs.

Nowadays when I get a bad review for one of my works it sometimes means that the book wasn’t the right one for the reader. That happens, of course. My friends love some authors who just don’t do anything for me. (And some people actually like anchovies on their pizza.) But sometimes not liking a book comes from a disconnect between what the reader wants from the work and what the work is intended to deliver.

My favorite bad review of The Desert of Souls came from a reader who believed the book was supposed to be a comedy, a la Terry Pratchett, despite the fact that there has been no marketing to suggest anything of the kind. One assumes that I would have gotten a one star review as well from someone who had desired the novel to be a story about cross-dressing penguins or a feminist literary tract set in the 19th century.

When I started to see these disconnects happen with my work I first felt sorry for myself (sniff) and wished all reviewers had to pass some kind of course so that they knew to approach a work by its own standards when they’re reading it. Does it succeed or fail as, say, a romance? Or even as a big fat fantasy, which is going to have different conventions even than other kinds of fantasy novels?

That, of course, is ridiculous, and instead of wishing they’d change I’ve learned to toughen up. When you’re on the other side of that fence – the critiqued rather than the critiquer – one of the first things you need to develop is a thicker skin and the ability to laugh, and I’ve gotten a lot better at both of those. Still, sometimes you can’t help but wince.

There is an art to review writing, and an art to taking a work apart. We need reviewers willing to call out a work when it doesn’t, uh, work, and who aren’t afraid to tell us the unvarnished truth. A well-written bad review can be a work of art. A really good one actually requires courage, especially if it flies in the face of the expected.

Yet as much as I strive to better my writing all the time, and as much as I desire to be courageous, I decided a while back not to send forth my review roosters of doom anymore. I only call attention now to works that I really enjoyed. I lean on reviewers to tell me when I should avoid watching a movie or reading a book, but I only ever talk about the stuff I love. Probably because I still cringe a little when I think what it must have felt like to get that stupid, scathing review I wrote all those years ago.

An earlier version of this essay appeared at Black Gate in 2012.

Howard Andrew Jones's Blog

- Howard Andrew Jones's profile

- 368 followers