Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 52

October 31, 2014

Lord Dunsany Re-Read: A Dreamer’s Tales, Part 3

This Friday brings us the third installment of our read through of a Lord Dunsany short story collection, A Dreamer’s Tales. My friends Bill Ward and C.S.E. Cooney have joined me once again to share thoughts. You can join in too — this book’s stories not only are quite short, they’re freely available as a Kindle download or through Project Gutenberg. It won’t take very long to catch up if you haven’t read them yet, so you might want to do so before you read any further.

This Friday brings us the third installment of our read through of a Lord Dunsany short story collection, A Dreamer’s Tales. My friends Bill Ward and C.S.E. Cooney have joined me once again to share thoughts. You can join in too — this book’s stories not only are quite short, they’re freely available as a Kindle download or through Project Gutenberg. It won’t take very long to catch up if you haven’t read them yet, so you might want to do so before you read any further.

This week we tackled four stories, “The Idle City,” “The Hashish Man,” “Poor Old Bill,” and “The Beggars.” We have a pretty simple review scale. One star is a standout and two stars is truly great.

I wish I could say I deliberately planned the creepiest stories from Lord Dunsany we’ve yet encountered to fall on Halloween, but it is just a happy chance. Unfortunately, this is my least favorite batch so far. Of the four, I felt like only “The Hashish Man” truly stood out, and I accordingly award it one star.

“The idle City” is a neat idea, but short as it is I thought it a trifle long, an interesting little experiment that could surely have been improved if it had more of a story. Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t like reading masses of cool description that don’t build to anything. That said, I think the final paragraph is first class, and I wish it concluded a better tale.

“The idle City” is a neat idea, but short as it is I thought it a trifle long, an interesting little experiment that could surely have been improved if it had more of a story. Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t like reading masses of cool description that don’t build to anything. That said, I think the final paragraph is first class, and I wish it concluded a better tale.

“The Hashish Man” is a weird little sequel to “Bethmoora” from our first week. It’s set in the real world, with Lord Dunsany himself appearing as the narrator. He has a perfectly rational conversation with a complete lunatic. It’s bizarre and funny and horrific and a little weird, and just the right length. I absolutely love that the hashish man politely excuses himself before hopping out the window.

“Poor Old Bill” is probably the first straight-up horror story we’ve read in the collection, complete with pirates, cannibals, curses, and eternal life. With all that in a few short pages you’d think I’d have remembered it better. I’m afraid, though, that it just didn’t really like it much. I’m probably not being fair to this one, but then I’ve never been much of a straight horror reader. Perhaps one of you will explain to me why it’s a classic or call out bits of brilliance I missed.

Despite having read it only a few days ago, I’m finding myself having to flip through the pages to even remind myself what happened in “The Beggars,” which is a pretty bad sign. I will say that on review I do very much like this: “Blessed be the houses, because men dream therein.” Likewise I enjoy the greeting “Be wonderful. Be full of mystery.” But as a story… it does little for me.

I would have to agree with you, Howard, about this latest batch. Some effective and interesting weird fiction, but I suspect we both prefer Dunsany in secondary world mode. How about you, Claire?

Claire: Bill, I think I prefer Dunsany when he tells stories. In either world!

Bill: “The Idle City” * I really liked the premise of a city that charges stories as tolls for entry, all so that a grieving King could find some consolation. I share the frustration that all of the interesting elements herein could have built a better story, but I’m not totally convinced the several nested tales we are treated to are necessarily unrelated to the larger story — but it seems more of a tantalizing promise. I at least could make no real connections. I am a sucker for stories within stories however, and I feel like this one will benefit from a second reading.

“The Hashish Man” * Dunsany getting a bit metafictional, confronting a lunatic who has visions of one of his own stories or, at least, into the mutual world of dream that inspires both fiction and madness. I really like the hashish-related countermeasures the Bethmoorans take against the ethereal visitor: gobbling hash by the spoonful in order to enter the same visionary state and scare him off.

“Poor Old Bill” Nautical weird tale, with some great descriptive passages. The premise of a crew trying to out-survive their former Captain and his lingering curse is great. Enjoyable enough, but not memorable by Dunsany standards.

“The Beggars” I suspect would reward a second reading, but I found it hard to enjoy and somewhat ambiguous. Some great imagery (all the beggars in the colored cloaks) and weirdness, but nothing about the piece really elevated the idea beyond sort of the standard weird fiction approach.

Still, even minor stuff from a major talent feels satisfying, and mostly any comparison I’m making with these pieces is between Lord Dunsany and himself.

Still, even minor stuff from a major talent feels satisfying, and mostly any comparison I’m making with these pieces is between Lord Dunsany and himself.

Howard: I think I’m doing the same thing, Bill. All of it’s of interest; it’s just some of these tales succeed better than others. Claire?

“The Idle City”: Howard, I can totally see what you mean about this story being a little experiment gone, if not wrong, then LONG. I myself would have snipped every reference to “cloud vapors” and “earth mist” right out. My eyes started to cross at that point. But you know what? I liked the cats. I like how they consider a miracle of fish falling from the sky their miracle. (More like their right.)

Lord Dunsany has this ineffable way of building up worlds I want very much to play in, and then just sort of leaving them empty, or populated with extras. No main characters. He’s more of a travel documentarian of his own internal dreamscapes than he is a storyteller. And the two things that got me most about this story occurred at the beginning and the ending, and were sewn of the same gut, I think. I loved that this indolent, idle city, where people waited at the gate to tell stories, was in fact not so idle as it seemed. That the great machinery of this city operated solely so that its grief-stricken king might sleep and forget, a while, his dead wife. That stories were, in fact, medicine. And that the city and its citizens so loved their king that it would take as tribute tales from near and far, and turn them into something healing.

The second thing, then, was, as you stated, the very last line. It centered around the King of Thebes, and called to mind (though Dunsany is bit gentler in phrasing) Shelley’s poem Ozymandias: “‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.” For these two kings, I give this story one star.

The second thing, then, was, as you stated, the very last line. It centered around the King of Thebes, and called to mind (though Dunsany is bit gentler in phrasing) Shelley’s poem Ozymandias: “‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.” For these two kings, I give this story one star.

Howard: That happens to be one of my favorite poems, and perhaps the only one I still have memorized. Both of you paid more heed to an important feature of this tale than I did — that the tales are meant to console the king. You have me wondering if I could reconsider my own evaluation. Anyway, back to you, Claire.

“Hashish Man:” For that little glimpse of Dunsany as a writer, as he’s groping to find a gracious way to acknowledge a fan who’s been “drinking from the bowl of dreams” a bit too deeply, I sort of love this story. “I said, ‘Oh, yes,’ and slowly searched in my mind for some more fitting acknowledgement of the compliment that his memory had paid me.” (JE T’AIME, DUNSANY!)

What I loved too was this idea of two kinds of dreamers: natural dreamers and (in a way) artificial dreamers. Dunsany visits Bethmoora through the active exercise of imagination; the hashish man through his drugs. I loved the idea that these two kinds of dreamers can come to a consensual imaginary world, though to one it is a reality that needs to be revisited, that concerns the dreamer enough that he’ll take hashish two days in a row, even knowing it’s not good for him, and rush out of his job at the insurance agency, and even leave his door unlocked “in case of accidents” just to return there and check up on things. His description of hashish is also marvelous–and funny. It made me snort, though there was sadness in it too. “It takes one literally out of oneself. It is like wings. You swoop over distant countries and into other worlds. Once I found out the secret of the universe. I have forgotten what it was, but I know that the Creator does not take creation seriously…”

What I loved too was this idea of two kinds of dreamers: natural dreamers and (in a way) artificial dreamers. Dunsany visits Bethmoora through the active exercise of imagination; the hashish man through his drugs. I loved the idea that these two kinds of dreamers can come to a consensual imaginary world, though to one it is a reality that needs to be revisited, that concerns the dreamer enough that he’ll take hashish two days in a row, even knowing it’s not good for him, and rush out of his job at the insurance agency, and even leave his door unlocked “in case of accidents” just to return there and check up on things. His description of hashish is also marvelous–and funny. It made me snort, though there was sadness in it too. “It takes one literally out of oneself. It is like wings. You swoop over distant countries and into other worlds. Once I found out the secret of the universe. I have forgotten what it was, but I know that the Creator does not take creation seriously…”

And then, I loved this–probably more than any other passage in the story: “And I met a huge grey shape that was the Spirit of some great people, perhaps of a whole star…” That fired up my imagination. A great star-dwelling people. Or stars as people. The spirit of a dead sentient star. I mean, JEEZ! I feel I ought to give this a star because of the aforementioned star.

“Poor Old Bill:” It was difficult for me to pay proper attention to this one, but little phrases flashed out. The opening line. “On an antique haunt of sailors, a tavern of the sea, the light of day was fading.” Doesn’t that just SLAM you into place. Except, once he gets you there, you just sit about and listen to another Ancient Mariner tell his wild-eyed tale. I suppose there’s a fine tradition of this sort of thing, but dang. I was ready to DO something. Seduce mermen or battle sea ghosts. Something vital. Something RIGHT THEN. But instead, Dunsany keeps us in a tavern and then tells a tale, putting us at a remove from the action of the story. We’re in the tavern. The STORY is in the sailor’s mouth.

Oh, but don’t you love this? “Both stars and fishes went about their businesses with cold, unastonished eyes.” I couldn’t give a rat’s patooty about Poor Old Bill himself, but I’d give something for a Captain with the superpower of sending the souls of his mutineers to the moon. If only that had been LITERAL instead of poetic device. The part about turning into cannibals and drawing lots was nicely understated, in a way that I found funny rather than horrific. But then, there could be something terribly, terribly wrong with me. I always preferred my horror to have the humorous element to it. It’s why I liked The Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy so much. No star, Lord Dunsany, dear. No offense.

Oh, but don’t you love this? “Both stars and fishes went about their businesses with cold, unastonished eyes.” I couldn’t give a rat’s patooty about Poor Old Bill himself, but I’d give something for a Captain with the superpower of sending the souls of his mutineers to the moon. If only that had been LITERAL instead of poetic device. The part about turning into cannibals and drawing lots was nicely understated, in a way that I found funny rather than horrific. But then, there could be something terribly, terribly wrong with me. I always preferred my horror to have the humorous element to it. It’s why I liked The Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy so much. No star, Lord Dunsany, dear. No offense.

“The Beggars:” You know, I wasn’t even looking forward to reading this one, but then… Then that opening line again! Dude, this guy has the power. The punch. Or maybe I just recognize a kindred spirit when I meet him. “I was walking down Piccadilly not long ago, thinking of nursery rhymes and regretting old romance.” KILLER! Possibly I’ve been melancholy recently, what with fall and old romances and all, but this one really got me.

The colors of the text are autumnal. “The merchants of London, they wear scarlet” contrasted with the next line “The streets were all so unromantic, dreary. Nothing could be done for them, I thought–nothing.” And then, a second slam into the story. “All the beggars had come to town.”

I love the narrator imagining the kind of coin he’d like to give this colorful array of beggars, thinking it unfitting to “offer the same coin as one tendered for the use of a taxicab (O marvelous, ill-made word, surely the pass-word somewhere of some evil order.)” HA! That was delightful. As was the description of the beggars, and this lovely end-cap, “And they begged gracefully, as gods might beg for souls.” Wham. That sent me straightway into story-brain. Gods as beggars of the soul. Wham.

I love the narrator imagining the kind of coin he’d like to give this colorful array of beggars, thinking it unfitting to “offer the same coin as one tendered for the use of a taxicab (O marvelous, ill-made word, surely the pass-word somewhere of some evil order.)” HA! That was delightful. As was the description of the beggars, and this lovely end-cap, “And they begged gracefully, as gods might beg for souls.” Wham. That sent me straightway into story-brain. Gods as beggars of the soul. Wham.

Reading on… Things I liked: Lamposts as lighthouses in the tides of night. “There were many wrecks an it were not for thee.” “Blessed be the houses, for men dream therein.” “The smoke that has stifled Romance and blackened the birds.” And I like, too, oh VERY MUCH, that Dunsany’s colorful beggars, Dunsany’s graceful gods of the soul, are walking through this dreary, dirty town and blessing it. The town that has become so vile that Dunsany cannot see its beauty any more, they are making sacred again. There is something very cathartic in their procession, like Morris Men dancing up the dawn on Spring Equinox. “Even thus they blessed the gutter, and I felt no whim to mock.” No, I feel no whim to mock either, Dunsany. There is a sweetness in this story that is more like ritual than narrative. It makes me breathe a little cleaner. It’s as if the story says to me too, the dreary vile me that broods and dwells, “Be wonderful. Be full of mystery.” So, yeah. I’ll give it a star.

Alright, those are our thoughts. We look forward to hearing what any of you have to say on the pieces. Next week we’ll look at only two, another longer one (so don’t wait ‘til the last minute) “Carcassonne,” and a short one, “In Zaccarath.” There are only a few more left after that. As some of my favorite military men said, “we’re getting very near the end.”

October 29, 2014

Catching Up

At some point in the near future I hope to post that I’ve finished the outline of my new book and then share some lessons I’ve learned from it. Right now, though, it’s still somewhere between halfway and two-thirds complete.

At some point in the near future I hope to post that I’ve finished the outline of my new book and then share some lessons I’ve learned from it. Right now, though, it’s still somewhere between halfway and two-thirds complete.

There are secrets and counterplots and manipulations going on within this one, and knowing when to reveal what and through whom is really the tricky thing. I ALWAYS appreciated Zelazny’s original Chronicles of Amber but as I try to replicate some of the feel of revealing layer upon layer of how the world works and who’s behind sinister plots I have more of an appreciation for what he himself pulled off. It’s not easy.

I couldn’t have told this story before now, I don’t think. I was messing with a version of it decades ago, but only the characters survive from that initial foray. Now I have the wisdom to know I need a very detailed outline to pull it off. I’m not starting without one, even if that means that several weeks are required to hammer a detailed outline into shape. Some writers don’t need them, but I’m pretty sure if I didn’t set out with a good plan in hand it would take me years to write this, seat of the pants, and explore all of the potential dead ends. I don’t intend to do that anymore.

I couldn’t have told this story before now, I don’t think. I was messing with a version of it decades ago, but only the characters survive from that initial foray. Now I have the wisdom to know I need a very detailed outline to pull it off. I’m not starting without one, even if that means that several weeks are required to hammer a detailed outline into shape. Some writers don’t need them, but I’m pretty sure if I didn’t set out with a good plan in hand it would take me years to write this, seat of the pants, and explore all of the potential dead ends. I don’t intend to do that anymore.

In other news I finally got around to watching the new Dark Shadows movie (it has been on endless re-run lately), and it proved even worse than I’d feared. It was so completely tone deaf. The sad thing is that there was so much potential there. Can I blame all of it on Tim Burton? One assumes that there were other decision makers helping him pilot that ship into the reef. Whoever was involved seems to have made the mistake so often made by people trying to re-envision material: they didn’t understand why fans loved the original show.

I only dimly remember Dark Shadows from when it used to be on re-runs when I was 8 or 9, but it seemed pretty cool. I’d watch it with one of my sisters, then a teenager, right after school. It was one of our few shared interests. I’ve only caught a few glimpses of it since and yeah, it looks a little cheesy. I understand in a lot of respects it’s really cheesy, and that microphones hanging into the shot and characters fumbling lines occurred regularly because of the show’s incredibly tight shooting schedule.

I only dimly remember Dark Shadows from when it used to be on re-runs when I was 8 or 9, but it seemed pretty cool. I’d watch it with one of my sisters, then a teenager, right after school. It was one of our few shared interests. I’ve only caught a few glimpses of it since and yeah, it looks a little cheesy. I understand in a lot of respects it’s really cheesy, and that microphones hanging into the shot and characters fumbling lines occurred regularly because of the show’s incredibly tight shooting schedule.

I think THAT is what the film makers seized upon — that the show was cheesy and had a vampire in it. What they didn’t get was that fans were transported enough by what they were seeing to look past the cornball stuff. When Dark Shadows was re-made there was a chance to tap into the compelling story elements that lay beneath it all rather than delivering a supernatural parody/comedy shlock fest. It’s almost like turning over the original Star Trek to be directed by someone who preferred Star Wars… I digress. I think that, as a result, Dark Shadows is probably dead for real. They’ve tried to re-envision it several times now and each time they’ve utterly failed. I doubt that any money will be spent on it again. And that’s too bad, because in the right hands there are some powerful themes that could be enjoyed by modern audiences.

October 27, 2014

Hardboiled Monday: Raymond Chandler

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.

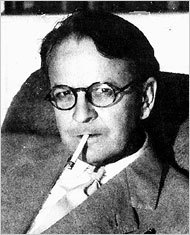

Today we’re looking at the works of one of the great masters of the genre, Raymond Chandler.

After having read every single Chandler novel — and I did spread them out so I could savor them — I understand why so many have declared him a master writer. It’s not just the cleverness and the quips and the wonderful metaphors, it’s the sense of place and the pace and the world-weary hero and, in most of them at least, the mystery itself. I have a handful of his short stories left to read, and I’ll be doing so slowly.

After having read every single Chandler novel — and I did spread them out so I could savor them — I understand why so many have declared him a master writer. It’s not just the cleverness and the quips and the wonderful metaphors, it’s the sense of place and the pace and the world-weary hero and, in most of them at least, the mystery itself. I have a handful of his short stories left to read, and I’ll be doing so slowly.

Chandler’s another author to whom I awarded a star. I know I’ll be re-reading a number of these books, probably more than once. I believe my favorite is the second, Farewell, My Lovely, but I think that The High Window and The Lady in the Lake aren’t too far behind it. I suppose I’d then rank his first, The Big Sleep, then The Long Goodbye, The Little Sister, and Playback. I didn’t find Playback as much of a letdown as I’d been led to believe, although it’s not a highlight. On the other hand, I wasn’t completely blown away by The Long Goodbye, either, which probably means I’ll be tarred and feathered because it’s supposed to be transcendent. Little Sister may actually be my least favorite because the end gets pretty convoluted.

I think in the later books Chandler grew less focused on the plot (and he sometimes tended to be a little loose on plot in any case — note the famous “who really killed the chauffeur” question from The Big Sleep) and more melancholy and, let us be fair, self-indulgent. He was going through some rough times, so it’s to be expected, but I’m not sure it makes for great reading. Perhaps all that turmoil in his life and melancholy in his prose means that The Long Goodbye is great literature, or perhaps some people thought so because Chandler directly deals with complaints about American society. Perhaps, though, readers just weren’t paying attention, because Chandler seems to be making social commentary during his mystery adventure stories from the very beginning. It’s not really as though any of these novels are superficial, although you CAN just read them as mysteries if you want.

I think in the later books Chandler grew less focused on the plot (and he sometimes tended to be a little loose on plot in any case — note the famous “who really killed the chauffeur” question from The Big Sleep) and more melancholy and, let us be fair, self-indulgent. He was going through some rough times, so it’s to be expected, but I’m not sure it makes for great reading. Perhaps all that turmoil in his life and melancholy in his prose means that The Long Goodbye is great literature, or perhaps some people thought so because Chandler directly deals with complaints about American society. Perhaps, though, readers just weren’t paying attention, because Chandler seems to be making social commentary during his mystery adventure stories from the very beginning. It’s not really as though any of these novels are superficial, although you CAN just read them as mysteries if you want.

Chris: Enough has been written about Chandler that I don’t feel I can add anything worthy of note. I do notice that, as is the case with Hammett (and especially The Maltese Falcon) Chandler’s work has become so blurred into modern entertainment, so thoroughly disseminated, absorbed and reproduced, so often imitated, parodied, and pastiched in everything from fiction to film to TV to comics to cartoons to commercials, that it has become strangely easy for modern readers to discount it. Chandler’s simile-laced style and his view of the detective as tarnished knight errant have so completely infiltrated every corner of pop culture that it seems many simply take the original work for granted.

Chris: Enough has been written about Chandler that I don’t feel I can add anything worthy of note. I do notice that, as is the case with Hammett (and especially The Maltese Falcon) Chandler’s work has become so blurred into modern entertainment, so thoroughly disseminated, absorbed and reproduced, so often imitated, parodied, and pastiched in everything from fiction to film to TV to comics to cartoons to commercials, that it has become strangely easy for modern readers to discount it. Chandler’s simile-laced style and his view of the detective as tarnished knight errant have so completely infiltrated every corner of pop culture that it seems many simply take the original work for granted.

So many others are standing on his shoulders that you can lose sight of the guy. Reading the original stuff will fix that. Even those who have read and appreciate the novels may find that the fresh intensity of Chandler’s short stories will sharpen their appreciation anew.

Howard: You’re absolutely right about Chandler. He’s been so often discussed and parodied that one wonders what to say that’s new. Certainly I have nothing more to say, critique wise.

Howard: You’re absolutely right about Chandler. He’s been so often discussed and parodied that one wonders what to say that’s new. Certainly I have nothing more to say, critique wise.

But I WILL say I didn’t realize how much of an influence he had over Roger Zelazny’s The Chronicles of Amber, my favorite series growing up. Zelazny’s narrator, Corwin, is pretty Marlowe-esque, and there’s even a scene in Farewell, My Lovely that feels to me like if must have inspired the opening of the first book of the chronicles, Nine Princes in Amber.

I suppose the most important thing I can say is that this writer should be read. A lot of times when a writer creates a classic (or classics, in Chandler’s case) it turns out the book is a slog (and usually means, as my kids say, that it has to be 50 years old and somebody dies at the end). But Chandler’s best work is truly astounding. You can read the books just as adventures/mysteries as you want, but they’re loaded with wonderful prose and observations upon the nature of humanity. I can’t believe I hadn’t read him until now, and I sternly urge other doubtful types to jump in with both feet and pick up these books. The short stories, as Chris says, are just as fine.

October 24, 2014

Lord Dunsany Re-Read: A Dreamer’s Tales, Part 2

This Friday brings us the second installment of our read through of a Lord Dunsany short story collection, A Dreamer’s Tales. My friends Bill Ward and C.S.E. Cooney have joined me once again to share thoughts. You can join in too — this book’s stories not only are quite short, they’re freely available as a Kindle download or through Project Gutenberg. It won’t take very long to catch up if you haven’t read them yet, so you might want to do so before you read any further.

This Friday brings us the second installment of our read through of a Lord Dunsany short story collection, A Dreamer’s Tales. My friends Bill Ward and C.S.E. Cooney have joined me once again to share thoughts. You can join in too — this book’s stories not only are quite short, they’re freely available as a Kindle download or through Project Gutenberg. It won’t take very long to catch up if you haven’t read them yet, so you might want to do so before you read any further.

This week we tackled only two stories, “Idle Days on the Yann,” and “The Sword and the Idol.” We have a pretty simple review scale. One star is a standout and two stars is truly great.

This week I happen to think we read two great ones, and I accordingly awarded each of them two stars.

Artwork by Sidney Sime.

I didn’t appreciate “Idle Days on the Yann” enough when I first read it some twenty years ago, probably because I made the mistake of reading it at the end of a long helping of Lord Dunsany. (Lord Dunsany can deliver a heady brew, and I at least can’t read too much in a row before I feel like I’m overwhelmed and begin to miss things.) In any case, at first blush it struck me as long and rambling. I’m a structuralist who loves well-conceived characters. Lord Dunsany just up and does whatever he wants with structure and doesn’t necessarily care about individuals in his fiction. I saw that the story was beautiful, I just missed the point of it.

Upon my return it was like seeing an old friend and suddenly remembering all the great times we’d shared and forgotten. Like that time we passed that haunting village on the river, or shared a fabulous bottle of wine with the ship’s captain, or talked with him under the star-shot darkness late one night about the divine.

Even though there is next to no dialogue and almost no one is named, there is a warmth and humanity to all the characters with whom the narrator interacts on ship. Lord Dunsany celebrates so often the joy and fragility of both life and beauty, and here he does so exceedingly well, enough that on re-reading the piece I, too, cherished my time upon the Yann. I know that I will return (and there are, in another collection, related stories, so I can come back in more ways than re-reading this tale).

Even though there is next to no dialogue and almost no one is named, there is a warmth and humanity to all the characters with whom the narrator interacts on ship. Lord Dunsany celebrates so often the joy and fragility of both life and beauty, and here he does so exceedingly well, enough that on re-reading the piece I, too, cherished my time upon the Yann. I know that I will return (and there are, in another collection, related stories, so I can come back in more ways than re-reading this tale).

I suppose I should point out to readers of ’70s era fantasy that this story is probably where Lin Carter got the idea for the giant carving from a single piece of ivory that appears in several of his short stories and novels

“The Sword and the Idol” I find masterful in a completely different way from “Yann.” It feels very true, like a folk tale told by a sociologist with great narrative skills. And what a comment upon human nature; that we humans so often choose fear over understanding. The whole change in the story’s society is motivated by envy and lust for power. We see the potential warmth in humanity in “Yann,” but we do not see evil. This story is a fine follow-up to the first, and they have a related thread that Bill addresses with great facility.

“Idle Days on the Yann” ** Religion seems to occupy the central place in this journey through the land of dream. The protagonist is of our world, the journey is one through a place of imagination, but everywhere again and again it is the gods and rituals of unfamiliar people that are described. The men of the ship traveling the length of the River Yann are of so many faiths that they pray in shifts, never more than one person praying to the same god lest they overwhelm the divinity. A whole city sleeps in order to dream their god, others dance or sacrifice in the face of natural and supernatural phenomena. Even small details reinforce this, like the merchant captain keeping a special reserve of wine in with his “sacred things.”

But we also see a flexibility in the divine — the narrator abandons his presumably Christian god in order to pray to a fantastical one, the merchant’s avowedly small and humble gods become great and terrible the second he is thwarted in a deal. The Helmsman of the ship offers a universal prayer, “to all the gods that are, to any god that hears” — the practical business of ship survival putting something as petty as denominational religion into focus. Is Dunsany saying the million faiths of man grow out of dream, the same source to satisfy the same need, with all the forgotten or potential faiths dotting the landscape of imagination, just waiting for us to sail by?

Our protagonist is along for the ride, his only purpose to see the place where the river meets the sea, the Gates of Yann. He encounters the strange, the other, he only but glimpses some terrible truths, such as the beast whose single tusk was large enough to carve into a city gate. And at the journey’s end the ship stops and goes no further, because the men of the ship are sailors of the river, not the sea. The sea can only be glimpsed from the river — much as the divine can only be glimpsed in a life of dream, a journey of imagination? I like that Dunsany muses so much on this, and that he squarely places our impulse for religion within the stew of myth and dreaming and mystery from which it emerged. Never does this feel like a parable, even when Dunsany/the narrator mentions returning to his poet’s home, where one can look one way and see the world of men, and the other to glimpse that of myth and fantasy. Thoughtful and thought-provoking, as well as offering plenty of a sense of wonder.

More Lord Dunsany inspired art by Sidney Sime.

“The Sword and the Idol” ** Another really good story, and another with religious underpinnings. I was reminded that many authors of this period seem to have done their own stone age tales and, based only on anecdotal reading, I suspect each story would reflect its author in an interesting way (just comparing this one with one by Wells would make a good essay!). Here we see the birth of a technology powerful enough to make a man and his line kings — and the counter to it, the birth of religion, a more potent force even than an iron sword in a world of stone. That potency comes from the imagination — we know what a sword does, but a god? It terrifies and humbles even the warrior king. The biblical language only reinforces the overall effect, but it also feels much more rooted in our world, sitting nicely but imprecisely somewhere in the hazy dawn of the human race.

And here’s Claire’s take:

IDLE DAYS ON THE YANN: A WHOPPING TWO STARS! **

SWORD AND IDOL: NO STAR.

“Idle Days on the Yann” reminded me how much I like a river journey story. Things don’t even need to happen on the river. It’s enough that you’re on a boat, with folks, and you’re seeing cool things. Bonus points for ACTION and DIALOGUE, but the forward momentum is already built in. This story reminded me of being in seventh grade again, when I’d read anything my father idly mentioned. I think he mentioned books on purpose, if you see what I mean. And suddenly, I’d read Ben Hur, and Tom Sawyer, and The Lord of the Rings. “Do you know Galadriel’s secret yet?” he’d ask. “Have you gotten to the chariot race?”

I’ve only read a few river stories before this. Huck Finn, of course (which I liked better than Tom Sawyer). George R. R. Martin’s Fevre Dream. Bujold’s Passage. There are some great scenes on the Nile in the early Amelia Peabody mysteries, as she’s traveling in her dahabeeyah. But I digress. The point is, RIVER STORIES. And Dunsany dreamed of the great river Yann, and the dream was enough. The first time I caught my breath in this story, it was when the sailors laughed at him for saying he was from Ireland. “There are no such places in all the land of dreams,” they tell him. And so the narrator regales them with the places of his fancy. Blue cities “sentinelled all round by wolves” and red-walled cities “where the fountains are.” And they’re all nodding, like they’ve been to these places before. “Xanadu, sure! Everyone’s been there. It’s right down the block from Valhalla.”

I’ve only read a few river stories before this. Huck Finn, of course (which I liked better than Tom Sawyer). George R. R. Martin’s Fevre Dream. Bujold’s Passage. There are some great scenes on the Nile in the early Amelia Peabody mysteries, as she’s traveling in her dahabeeyah. But I digress. The point is, RIVER STORIES. And Dunsany dreamed of the great river Yann, and the dream was enough. The first time I caught my breath in this story, it was when the sailors laughed at him for saying he was from Ireland. “There are no such places in all the land of dreams,” they tell him. And so the narrator regales them with the places of his fancy. Blue cities “sentinelled all round by wolves” and red-walled cities “where the fountains are.” And they’re all nodding, like they’ve been to these places before. “Xanadu, sure! Everyone’s been there. It’s right down the block from Valhalla.”

It was then I realized that the River Yann was nowhere in this world, and that I too might sail it. So I settled in for the ride, monsters and ivory gates and all.

Lord Dunsany

The friendship between the captain and the narrator was, I think, the most striking thing about this story. I mean, I loved the thing with the gods, and the men who prayed in shifts, and the idea that night comes down on men who pray and men who do not, and the generosity and flexibility of religious views herein… But the friendship (the word that sprang to mind was “BROMANCE,” as if Simon Pegg and Nick Frost were playing the leads in a film adaptation called “Blood and Ice Cream and the River Yann”) was what got me. I read the description of the wine the captain shared, “heavy yellow wine from a small jar which he kept apart among his sacred things. Thick and sweet it was, even like honey, yet there was in its heart a mighty, ardent fire which had authority over the souls of men,” and my mouth started watering. Not just for the prose, or for want of this wine, this wine and no other, but for the captain of a riverboat one might meet in a dream, who you know to be your friend because he shares this wine with you, and no one else. It made me all, you know, Dunsanied. By which I mean, full of longing and scorch marks and elusive ambrosia.

Their parting made me very somber. But I think they will meet again, those two friends. And it made me hope for dreams I will later remember, and turn into stories. I do meet friends in dreams, sometimes, and then write about them. Maybe that’s my way of sharing sacred wine.

Gracious. Well, it was a two-star story. There was a lot to respond to. And I didn’t even talk about that awesome scene of bargaining, with the jeweled scimitar and the lifting of the beard. Nor of the great gate, or of the description of dancing. Suffice to say that now I wish to be known, not only as C. S. E. “Tiger of the Gods” Cooney, but Claire “Haughty Queen of Distance Conquered Lands” Cooney as well. If you please.

Gracious. Well, it was a two-star story. There was a lot to respond to. And I didn’t even talk about that awesome scene of bargaining, with the jeweled scimitar and the lifting of the beard. Nor of the great gate, or of the description of dancing. Suffice to say that now I wish to be known, not only as C. S. E. “Tiger of the Gods” Cooney, but Claire “Haughty Queen of Distance Conquered Lands” Cooney as well. If you please.

I am less enthusiastic about “The Sword and the Idol.” No women. Stone axes. Iron sword. A son of no account. The best part was the god in the tree. And how it wasn’t one until Ith said it was. Or fancied it was.

See, what I found frightening about this was not the power of the gods over men, or how a god’s idea of punishment differs from man’s, but the power of man to distort, by his own imagination, a tree into a god… And then get his whole darn village to fear the thing, and sacrifice to it.

See, what I found frightening about this was not the power of the gods over men, or how a god’s idea of punishment differs from man’s, but the power of man to distort, by his own imagination, a tree into a god… And then get his whole darn village to fear the thing, and sacrifice to it.

But I loved the wolves, and I loved the prophetic dogs: “the fierce and valiant dogs that belonged to the tribe” who “believed that their end was about to come while fighting, as they had long since prophesied it would,” and who, when the wolves slunk away, “cried out to them and besought them to come back.”

Maybe I’m just not really into cavemen. I am, however, always interested in the notion of, “Who had that idea first?” The first person to use garlic in a recipe. The first person to realize that pizza was a great idea. The inventor of the wheel. The harnessers of electricity. So. Who made the first iron sword? And, then, because it wasn’t the sword’s true time, sacrificed it to a tree.

It is a compelling idea. I should have liked to see Dunsany’s face while he dreamed of it. I wonder if he got a certain glint in his eye.

It is a compelling idea. I should have liked to see Dunsany’s face while he dreamed of it. I wonder if he got a certain glint in his eye.

And this is purely a word-choice thing, but I love how “Idle” from the first title and “Idol” from the second title partner up in my mind. It seems like somebody was playing around. Whether it was Dunsany or his editor, I do not know, but I kind of love them for that.

Claire, I’d been thinking that myself about the word play on Idle/Idol. I’m sure it was a deliberate choice, because the next story has “Idle” in it as well!

Anyway, there’s the take from the three of us, but I’m hoping you’ll join in the discussion. Claire and Bill and I will be wandering through the site every now and then to respond to your own observations.

Next Friday we’ll discuss four shorter stories: “The Idle City,” “The Hashish Man,” “Poor Old Bill,” and “The Beggars.” Hope to see you here!

October 23, 2014

Captain Blood

Speaking of Sabatini, Fletcher Vredenburgh and I take a long look at the three Captain Blood books and discuss their fine merits… and a few jarring problems, over at Black Gate today.

Speaking of Sabatini, Fletcher Vredenburgh and I take a long look at the three Captain Blood books and discuss their fine merits… and a few jarring problems, over at Black Gate today.

October 22, 2014

Link Day

I’m deep in the midst of my new outline and have a number of errands to run, so I must keep today’s post short, although I want to give two shout-outs.

I’m deep in the midst of my new outline and have a number of errands to run, so I must keep today’s post short, although I want to give two shout-outs.

First, to Erin Evans’ Fire in the Blood. I don’t usually read epic fantasy, but I was terrifically impressed by her character arcs, driving plot, and unveiling of mystery. I’ve been trying to think my way through a succinct blurb that says all that, and I’ll do so in the next couple of days.

Second, last night my wife and I drove south to the Evansville Barnes & Noble to listen to our friend Mark Rigney read from his new Renner & Quist novel, Check-Out Time. It sounds just as fine as the Black Gate review described it, so I hope you’ll join me in picking up a copy for yourselves.

Second, last night my wife and I drove south to the Evansville Barnes & Noble to listen to our friend Mark Rigney read from his new Renner & Quist novel, Check-Out Time. It sounds just as fine as the Black Gate review described it, so I hope you’ll join me in picking up a copy for yourselves.

And then, for you folks reading along with Lord Dunsany, I found an interesting essay from Great Science Fiction and Fantasy Links. Take a look, and don’t forget to join in Friday for the next two tales we’re reading, “Idle Days on the Yann” and “The Sword and the Idol.”

October 20, 2014

Hardboiled Monday: Fast One

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.

I remain disappointed that there was so little interest voiced about the Howard Browne book from last week. As far as I’m concerned, that’s one of the finest books on the entire list, but I think we got more FB Likes and comments on that silly Spam Haiku post on Wednesday. If you somehow missed our discussion on The Taste of Ashes, take a look. And if you like this stuff, by God, order a copy of the complete Paul Pine detective stories from Stephen Haffner. Just trust me on this one.

Today we’re looking at Fast One, by Paul Cain.

This WAS a fast one. A blizzard of events swirls the central character, Kells, into a series of political and criminal machinations. He then does his best to twist things to his own advantage. The only problem is that he may not know when to stop, and he has this nagging character flaw for a criminal mastermind – he’s loyal to his friends. This novel is terse, brutal, powerful, unforgettable.

This WAS a fast one. A blizzard of events swirls the central character, Kells, into a series of political and criminal machinations. He then does his best to twist things to his own advantage. The only problem is that he may not know when to stop, and he has this nagging character flaw for a criminal mastermind – he’s loyal to his friends. This novel is terse, brutal, powerful, unforgettable.

Chris: In the indispensable review collection 1001 Midnights, Bill Pronzini wrote that by the time this Black Mask classic comes to its relentless conclusion the reader can feel a sort of “breathless despair,” and this strikes me as weirdly accurate. Commonly considered a benchmark in the ultra-hardboiled, terse style made famous by Hammett, Fast One is stripped-down, sharp and merciless as a stiletto. The narrative hurtles along through all manner of gritty, eminently believable scenes of Depression-era lawlessness with such clipped speed that the reader cannot lose focus on the page for a second for fear of missing something. It’s exhausting, an example of style taken close to its limit, but it is a novel that, once read, is never forgotten.

Howard: Didn’t you tell me that Hammett had called it the North Pole of hardboiled — that you couldn’t make something any more terse and still decipher what was going on? And yet, oddly enough, I found myself more attached to Kells than I’ve so far been to Hammet’s heroes –either Spade or the Continental Op. Despite the fact he’s a criminal, there’s a certain warmth to Kells. How does the rest of Cain stand up to this lone book?

Howard: Didn’t you tell me that Hammett had called it the North Pole of hardboiled — that you couldn’t make something any more terse and still decipher what was going on? And yet, oddly enough, I found myself more attached to Kells than I’ve so far been to Hammet’s heroes –either Spade or the Continental Op. Despite the fact he’s a criminal, there’s a certain warmth to Kells. How does the rest of Cain stand up to this lone book?

Chris: Chandler described Fast One as “some kind of high point in the ultra hard-boiled manner.” I can’t recall who said the novel was the North Pole of hardboiled writing, meaning that once you got to the North Pole you simply couldn’t go any farther North, that the book took that style just about as far as it was possible to go.

Cain’s short stories are excellent and there are only a handful of them. Sharp, cold little things that reward re-reading.

Here’s a link to a book collecting all of Paul Cain’s stories from the great Black Mask magazine.

October 17, 2014

Lord Dunsany Re-Read: A Dreamer’s Tales, Part 1

This week launches the first instcallment of our read through of a Lord Dunsany short story collection, A Dreamer’s Tales. My friends Bill Ward and C.S.E. Cooney have been kind enough to join me in posting their thoughts. You can join in too — this book’s stories not only are quite short, they’re freely available as a Kindle download or through Project Gutenberg. It won’t take very long to catch up if you haven’t read them yet, so you might want to do so before you read any further. We began with the first five of them.

This week launches the first instcallment of our read through of a Lord Dunsany short story collection, A Dreamer’s Tales. My friends Bill Ward and C.S.E. Cooney have been kind enough to join me in posting their thoughts. You can join in too — this book’s stories not only are quite short, they’re freely available as a Kindle download or through Project Gutenberg. It won’t take very long to catch up if you haven’t read them yet, so you might want to do so before you read any further. We began with the first five of them.

We could have started the re-read with any of Lord Dunsany’s eight short-story collections, but I thought the opening entries in A Dreamer’s Tales were quite strong and hopefully would convince newcomers to stick with him.

Here’s how I rate them. One star is a standout. Two stars means it’s among Lord Dunsany’s very best.

* “Poltarnees”

** “Blagdaross”

* “The Madness of Andelsprutz”

“Where the Tides Ebb and Flow”

“Bethmoora”

Lord Dunsany can often be a little light on plot or even plotless, though he’s a master of breathtaking description and at peering into the hearts and the desires and fears of human beings. “Poltarnees,” though, does have a plot, and it reads like a wondrous, forgotten fable. Naturally it’s threaded through with the lyrical language for which Lord Dunsany is known. I happen to think that it kind of skewers some traditional fable tropes because it hardly provides the expected ending. But then many old fables with young people concern themselves with love and romance between humans and this one is about the power of longing.

Lord Dunsany can often be a little light on plot or even plotless, though he’s a master of breathtaking description and at peering into the hearts and the desires and fears of human beings. “Poltarnees,” though, does have a plot, and it reads like a wondrous, forgotten fable. Naturally it’s threaded through with the lyrical language for which Lord Dunsany is known. I happen to think that it kind of skewers some traditional fable tropes because it hardly provides the expected ending. But then many old fables with young people concern themselves with love and romance between humans and this one is about the power of longing.

“Blagdaross” is more like a collection of moments gathered as a camera pans over a group of storytellers — a very strange group indeed — but every one of their stories is fascinating. I first read this one more than fifteen years ago and I’ve never forgotten key moments of it. Blagdaross remains my favorite of the storytellers, but the cord was even more terrible than I remembered, and this time its tale stayed with me longer, like the lingering effects of a nightmare.

“The Madness of Andelsprutz” — what a beautiful little story that no one but Lord Dunsany might have conceived, where he breathes life into entire cities. Claire writes more eloquently about it below, and then Bill has some excellent observations about some of its aspects that I had taken for granted.

“Where the Tides Ebb and Flow” is a haunting read, but I don’t number it among Dunsany’s best.

“Bethmoora” is a variation on one of Dunsany’s themes — that of an astonishing city that is faded and lost, described with great beauty. But he does it better elsewhere.

Take it away, Claire!

TIGER OF THE GODS?!! I want that to be on my tombstone. If I have to give them stars, I suppose I’d rate them like this:

* “Poltarnees”

** “Blagdaross”

** “The Madness of Andelsprutz”

** “Where the Tides Ebb and Flow”

* “Bethmoora”

With Poltarnees I found myself constantly highlighting and copying the text in my Kindle, and then text messaging it to people, or posting it to Facebook, or Twitter. It kept snagging me. Snagging my attention, like sea breeze from a mountain. It made me want to leave my Inner Lands and go search for something far distant. But it dissatisfied me too, for the kind of reader I am. To be fair, that kind of dissatisfaction generally makes a nuisance of itself until I rectify it in my own writing. I keep seeing the Princess/Priestess setting off for the mountains, for the sea itself. Maybe as an old woman. Maybe her final journey. And maybe she meets an old fisherman on the docks, and recognizes him. And maybe she tells him, “You were wrong. Even at my most beautiful, I was never so beautiful as this.” And the moon looks down on her, and shines upon her brow, and hates her no more.

With Poltarnees I found myself constantly highlighting and copying the text in my Kindle, and then text messaging it to people, or posting it to Facebook, or Twitter. It kept snagging me. Snagging my attention, like sea breeze from a mountain. It made me want to leave my Inner Lands and go search for something far distant. But it dissatisfied me too, for the kind of reader I am. To be fair, that kind of dissatisfaction generally makes a nuisance of itself until I rectify it in my own writing. I keep seeing the Princess/Priestess setting off for the mountains, for the sea itself. Maybe as an old woman. Maybe her final journey. And maybe she meets an old fisherman on the docks, and recognizes him. And maybe she tells him, “You were wrong. Even at my most beautiful, I was never so beautiful as this.” And the moon looks down on her, and shines upon her brow, and hates her no more.

That’s basically my reaction. In a nutshell. But none of THAT was in the ACTUAL STORY. My final take? For a fable it made a good HORROR STORY! That last line? SHIVER ME TIMBERS! I still wish the princess got to effect her own escape. She’d’ve made a good PIRATE on that terrible, terrible sea.

“Blagdaross” was so CREEPY and adorable!!! It was like… The Velveteen Rabbit meets Toy Story 2 meets, I dunno, Don Quixote. I loved the cork especially, who stood sentinel for the leaping wine. And feared the cord, the grim cord and its purpose. And felt a great fellow feeling for the unstruck match.

But Blagdaross! So bitter and exultant! So sure of his place and the depth and breadth of his soul! So true to his name. Ah, man. Made me hate, for a second, to be a grown up.

“The Madness of Andelsprutz:” I love the idea of GHOST CITIES!!! This story was well-placed on the heels of “Blagdaross,” for they both concern the living souls of inanimate things. From discarded trash to dead cities is a mighty leap, made palatable by the logic of extrapolation. I loved the entire passage about “some cities are this, others are this,” but all having a certain “way about them.” And then, the horrible feeling of entering a city without any way about it at all. That stuck deep. I feared the story was going to be about a plague. But it wasn’t. Siege, though–and the ravages of war and waiting.

“Ebb and Flow” was another nightmarish story. With that peculiar thing Dunsany does where he gives souls to things generally considered lifeless. Those “mean houses” and a man’s poor bones. It broke my mind a little, the line about longing for a proper burial: “for the great caress of the warm Earth or the comfortable lap of the sea.”

“Ebb and Flow” was another nightmarish story. With that peculiar thing Dunsany does where he gives souls to things generally considered lifeless. Those “mean houses” and a man’s poor bones. It broke my mind a little, the line about longing for a proper burial: “for the great caress of the warm Earth or the comfortable lap of the sea.”

There’s a rocking and a lapping in the text itself. It’s delicious. It brings to my mouth the taste of mud and brine. Again, it’s a story almost wholly of atmosphere, of ritual, and not of plot at all. Hardly there is a character except the bones, the men who carry out the rite, the mean houses, and the tide itself. But one can dwell indeterminately in this place or leave it suddenly, but not quite forget it.

And in the end the whole thing turned exultant, like a dream that goes from dankness and despair and sour adrenalin to a burst of clarity just before waking. For that, and for the thing he did that made me think of burial in a way I’ve never thought of burial before… For those things, two stars. For the taste in my mouth.

I’m digging the placement of “Bethmoora” behind “Ebb and Flow.” Another first person, another setting in Benighted London. “Behold now night is dead,” he writes. But it isn’t, quite. Night breathes in his words. And then he leaps us into this fable of Bethmoora, through a pair of green copper gates, into a desert. He does that in the next breath. Nice segue, Dunsany. Dunsany, I SALUTE YOU!

Gosh, this dude’s got DREAD and LONGING down to a frikkin’ art form. Like he’s flinging his soul out from a well like a grappling hook, trying to catch hold of something that will save him. I should totally look him up on Wikipedia. His writing makes me wonder how he died.

And now we’ll hear from Bill:

And now we’ll hear from Bill:

Howard, I agree completely with your star ratings.

“Poltarnees, Beholder of Ocean” is the sort of story I associate with Dunsany, and felt like familiar ground and it’s the one I have the most to say about. Dunsany really does evoke the feel of genuine myth, everything from names and structure, to the metaphorical logic that underpins the story. I love the digressions in this, scenes like the Kings comparing the Princess to natural phenomena to determine if she is truly beautiful enough to rival the sea, or the gariach hunter’s own story of his first hunt. They feel like the kinds of things that accumulate around real myths, the stuff that gets stuck in because a dozen generations have told and retold the story among themselves. The highly poetic language and the personification of natural features and phenomena all reinforce this.

The lesser version of this story would probably solely be about beauty –those who behold the sea never return because of some great aesthetic longing it provokes. But instead it seems to me it’s about experience, wisdom, and closely mirrors a religious awakening (the sea, after all, is the god of the landlocked kingdoms). People never turn away from the sea once they behold it not because it uplifts them, or because it is the “supreme beauty” that those who have never seen it imagine it to be, but because it shows them something undreamt of in their own experience, something both beautiful and terrible and much more besides. It changes the world by being in it. They can’t go back down the mountain in the same way one cannot regain innocence, or return to the outlook of an earlier age.

In the end, the abstraction of the sea is easily switched from god to devil for those who haven’t seen it and now wish to curse it, because they never

understood it for what it was in the first place; you either have experienced it, or you have not.

“Poltarnees” was my favorite of the five, but “Blagdaross” is the better story in my opinion, and one I immediately realized I’d read before, though

I couldn’t tell you where. Seems to me it’s about imagination, both the fertile imagination of the writer, and the redemptive quality (and “largeness of soul”) imagination has on poor forgotten Blagdaross himself. You’d have to have an imagination to glimpse the former lives of these discarded things, but only one of them can be reborn through that same medium, and can get back what was lost. A really fine, fascinating, uplifting tale, and a celebration of fantasy and innocence.

“The Madness of Andelsprutz,” like “Bethmoora,” is about a fabulous city, though it invites us to look at the very soul of the city, (and I agree this is the better of the two). One thing I noticed here that Dunsany seems to do throughout is his free mixing of real world details with wholly invented, “secondary world” ones, something you don’t see anymore (and if you do, it almost always detracts from the intended result). So, the fabulous Andelsprutz is consoled by Athens and Carthage, just as the “river of the sea” in “Poltarnees” flows toward Hercules. Again, it powerfully evokes the language of legend and myth while remaining equal in invention to the rich layers of our inherited past.

“The Madness of Andelsprutz,” like “Bethmoora,” is about a fabulous city, though it invites us to look at the very soul of the city, (and I agree this is the better of the two). One thing I noticed here that Dunsany seems to do throughout is his free mixing of real world details with wholly invented, “secondary world” ones, something you don’t see anymore (and if you do, it almost always detracts from the intended result). So, the fabulous Andelsprutz is consoled by Athens and Carthage, just as the “river of the sea” in “Poltarnees” flows toward Hercules. Again, it powerfully evokes the language of legend and myth while remaining equal in invention to the rich layers of our inherited past.

“Where the Tides Ebb and Flow” reminded me of Poe, and surprised me a bit; it’s not what I associate with Dunsany. The conceit of waking up from a dream is nowhere near as acceptable today as it must have been when it was written, and overall it just felt like a solid short from a guy that knows the form, and his audience, very well. The interesting ideas it raised felt negated by the ending.

“Bethmoora” is enjoyable, but didn’t really resonate beyond just Dunsany being Dunsany (not that that isn’t enough!)

Overall, glad to be reading Dunsany after a long hiatus, he really is something amazing.

There’s the take from the three of us, but I’m hoping you’ll join in the discussion. Claire and Bill and I will be wandering through the site every now and then to respond to your own observations (although I might be a day or two late this week).

Next week we’ll only read two stories — “Idle Days on the Yann” and “The Sword and the Idol,” and I hope you’ll read along. Yann is so dreamy and poetic that it really should be savored slowly, methinks. It’s also longer than standard for Lord Dunsany. You could overdose on his prose by reading too much too fast.

Here’s my final summation for the week:

Dunsany is great.

Blagdaross is best of all.

Can’t wait to read more.

October 15, 2014

Spam Haiku

Some stunning work from Heather Jansch.

Bill Ward and I were talking the other day about the vast waves of spam that wash up from the Internet onto our sites and how it could be inspiring. After all, wonderful artwork can be fashioned from driftwood swept in from the sea. Could we do the same with phrases clipped from tens of thousands of messages and “friendly posts” for our blog sites trapped by our spam filters?

Yes. Yes, we could. And surely we have shaped it into art destined to shine like a beacon and illuminate the way for future disciples.

Incidentally, Bill searched for Spam Haiku and found a Haiku site dedicated to the actual food product. Really and truly. Ours is different from that, though. We’re artistic innovators, we are, fashioning masterpieces culled from Internet spam.

Well, maybe not masterpieces. Surely not masterpieces.

They’re not true Haiku,

but perhaps they will amuse.

They fit the meter.

Anyway, our creations can be found below, made entirely from phrases we found in our spam filters. Some were trimmed for size, but it’s surprising how much of it simply worked as it was.

Marvelous posting.

You could be a great author!

Visit and find deals.

You are so gifted.

You are so gifted.

No one gives topics like you.

Can I quote them? Handbags.

Ugg girl boots for sale.

I know this is off topic,

where to find words?

Is your theme custom?

Authentic Nike shoe sale!

Fascinating blog!

Impressive content.

I truly enjoy your blog.

Problem with hackers?

China insights on how

NFL jersey helped me

get rich and famous.

With havin so much

do anyone plagiarize?

You know any ways?

Classic Michael Kors

charm tassel convertible

shoulder tote dove sale.

Counterfeit jersey.

The most beneficial tricks

which experts claims fools.

I’ll just sum it up.

Have helpful tips to blog?

Would appreciate.

Feeling a little

limp? Buy Cialis by mail

at wholesale prices.

Does anyone fall

for word salad compliments

and follow these links?

October 13, 2014

Hardboiled Monday: Howard Browne

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details here. And earlier discussions are here.

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details here. And earlier discussions are here.

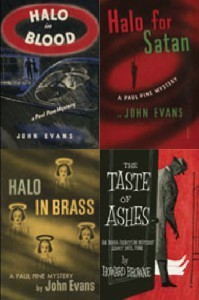

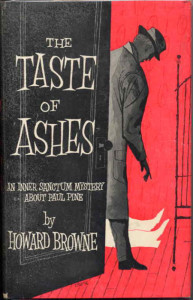

Chris Hocking recommended all of Browne’s mystery novels: the four Paul Pine books and a standalone, Thin Air. I couldn’t lay hands on the first three Paul Pine books, and Thin Air got lost in the mail, but Hocking had given me The Taste of Ashes. It came wrapped in a deceptively mediocre cover that provided little clue as to how outstanding the prose within would be.

Ashes is not only one of the finest hardboiled novels I’ve read, not only one of the finest mysteries I’ve read, but one of the finest books I’ve ever read in a long history of book reading. It’s the last of Browne’s detective novels, but the only one I had on hand, so I started there. It easily got a gold star. The moment I finished it I knew I’d be reading it again, and I am set on reading more Browne. I was immensely impressed. I’m waiting to read the rest of the Paul Pine detective novels to be released in hardback through Haffner Press. Hurry up and print them already, Stephen! Given the rarity of all four of these books, given that there’s more Paul Pine stories inside, and given the excellence of the one I read and the high quality of Haffner Press products, $40.00 is a bargain.

Chris: I got peeved with Howard because he read The Taste of Ashes before the others in the series, and especially because he hadn’t finished reading Chandler yet. An over reaction of course, but while all of the books in this series are good, The Taste of Ashes is both the last and the best. Reading Chandler’s work first actually sharpens appreciation of this novel. Browne is, to my mind, the finest direct follower in the Chandler style–loading the pages with lush similes, tight dialogue and head-spinning plot twists. If you enjoy classic American detective fiction this books brings it on so heavy you won’t want to stop reading.

Chris: I got peeved with Howard because he read The Taste of Ashes before the others in the series, and especially because he hadn’t finished reading Chandler yet. An over reaction of course, but while all of the books in this series are good, The Taste of Ashes is both the last and the best. Reading Chandler’s work first actually sharpens appreciation of this novel. Browne is, to my mind, the finest direct follower in the Chandler style–loading the pages with lush similes, tight dialogue and head-spinning plot twists. If you enjoy classic American detective fiction this books brings it on so heavy you won’t want to stop reading.

The Taste of Ashes has an absolutely tragic publication history. Apparently this book had only a single hardcover printing in 1957, and when it was time to issue it in paperback the publisher insisted it be cut substantially. Browne didn’t want to do that to his novel, so it wasn’t given a paperback printing until little Dennis McMillan press brought it out in 1988. I was delighted to finally get my hands on it, but I can’t help but wonder how much better known the book might be if it hadn’t been out of print for thirty years. It is pure sacrilege to say this of what is undeniably a Chandler pastiche, but Taste of Ashes is so well wrought that I believe it stands up to the best of Chandler.

Howard: Having now read all of the Chandler novels I think I can easily say that The Taste of Ashes stands up beside Chandler’s lyrical best. And this may be heresy, but I honestly think The Taste of Ashes is better than a number of the Marlowe novels. Chris pointed out to me that Browne is a tighter plotter, and he’s absolutely right. Chandler’s plots can wander a little. The Taste of Ashes never did. I’m very, very interested in seeing the rest of the Paul Pine novels and related stories Haffner’s dredged up for his collection.

Howard: Having now read all of the Chandler novels I think I can easily say that The Taste of Ashes stands up beside Chandler’s lyrical best. And this may be heresy, but I honestly think The Taste of Ashes is better than a number of the Marlowe novels. Chris pointed out to me that Browne is a tighter plotter, and he’s absolutely right. Chandler’s plots can wander a little. The Taste of Ashes never did. I’m very, very interested in seeing the rest of the Paul Pine novels and related stories Haffner’s dredged up for his collection.

Chris: You’ll enjoy the earlier Browne novels. They’re great private eye fiction. It’s just that they don’t pack the weight of The Taste of Ashes. The first two, Halo in Blood and Halo for Satan, are fast and fun, lighter and crackling with wry humor in the Chandler style. I thought Halo in Brass a bit more serious in tone, and I recall I found its plot as complex as a topology problem. All fine stuff I need to re-read. But The Taste of Ashes stands apart. I’ve already re-read that one. And at some point I know I’ll do it again.

Howard Andrew Jones's Blog

- Howard Andrew Jones's profile

- 368 followers