Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 25

January 30, 2017

First They Came…

If you’re going to make a sweeping change with the stroke of a pen that can potentially affect millions of people, then you’d best have contemplated the ramifications of what you’re doing. You’d best understand the small details and not just intend to do right. If you’re changing a rule, directive, or law then you have to understand the whys and wherefores of that rule, directive or law before you make alterations.

If you’re going to make a sweeping change with the stroke of a pen that can potentially affect millions of people, then you’d best have contemplated the ramifications of what you’re doing. You’d best understand the small details and not just intend to do right. If you’re changing a rule, directive, or law then you have to understand the whys and wherefores of that rule, directive or law before you make alterations.

But through a combination of arrogance and ignorance, our new president has generated a storm of misery, catching up people who loyally served our country’s military as translators, people who already have been thoroughly vetted and have green cards, people who are thoroughly vetted and have visas, and thousands and thousands of innocent children — and those are just the most obvious examples of his poorly wrought executive order.

I am appalled and enraged.

This site will never be devoted to political subjects. But this is not a political subject. This post is about a humanitarian disaster brought about by careless action.

So far I have no public appearances scheduled this year. But you may well see me in public with a sign until this nonsense is addressed. And God help us, given this president’s inability to admit wrongdoing and blindness to his own lack of understanding, this is probably only the start of things worth protesting. I’ll see you on the lines.

January 27, 2017

My New Book

My friend Mick dropped me a line the other day asking for details on my new Pathfinder book, Through the Gate in the Sea. First off, I have to confess to me that it’s strange to think of it as “new” because I turned it over in 2015, and addressed some editorial feedback last summer. It’s felt over and done with for a while — except of course it’s never been released!

My friend Mick dropped me a line the other day asking for details on my new Pathfinder book, Through the Gate in the Sea. First off, I have to confess to me that it’s strange to think of it as “new” because I turned it over in 2015, and addressed some editorial feedback last summer. It’s felt over and done with for a while — except of course it’s never been released!

It’s the sequel to my third Pathinder novel, Beyond the Pool of Stars, which was my favorite of the Pathfinder novels published so far. I think I like this one at least as well, and there’s a new point-of-view character in it that I really enjoyed writing. Well, make that two, although one is new to the narrative.

If you liked what you saw in Beyond the Pool of Stars, with it’s Indiana Jones style search for missing treasure crossed with a Burroughsian jungle trek plus some pretty cool lizard folk characters, you’ll find more of it. I think the tension’s ratcheted up as our heroes track down clues to a lost city of Mirian’s lizard folk friend Jekka’s people, which may be fully inhabited. The problem is it lies through a mystical gate in the sea, and other people want to get there before them because of the sorcerous secrets that may lie behind.

Here’s the official descrip:

Deepwater salvager Mirian Raas and her bold crew may have bought their nation’s freedom with a hoard of lost lizardfolk treasure, but their troubles are only just beginning in this sequel to Beyond the Pool of Stars.

When Mirian’s new lizardfolk companions, long believed to be the last of their tribe, discover hints that their people may yet survive on a magical island, the crew of the Daughter of the Mist is only too happy to help them venture into uncharted waters. Yet the perilous sea isn’t the only danger, as the devil-worshiping empire of Cheliax hasn’t forgotten its defeat at Mirian’s hands, and far in the east, an ancient, undead child-king has set his sights on the magical artifact that’s kept the lost lizardfolk city safe all these centuries.

I was ably assisted by the talented Chris Jackson, friend and fellow Pathfinder novelist, who provided a slew of feedback both on the prose and on the sailorish bits specifically, for Chris lives on the sea and knows his stuff and this novel is crammed with seagoing action.

Anyway, it’s available now for pre-order and should come your way in February.

January 25, 2017

Belated Birthday

Here’s to Robert E. Howard, creator of my favorite genre, sword-and-sorcery, on the anniversary of his birth. Raise high your goblets and drink deep.

Here’s to Robert E. Howard, creator of my favorite genre, sword-and-sorcery, on the anniversary of his birth. Raise high your goblets and drink deep.

What is best about Robert E. Howard’s writing? The driving headlong pace, the seemingly inexhaustible imagination, the splendid cinematic prose poetry, the never-say-die protagonists? It is hard to pick one thing, so it may be simpler to state that Robert E. Howard possessed profound and often astonishing storytelling gifts. Without drowning his readers in adjectives (he had the knack of using just enough adjectives or adverbs, and knew to let the verbs do the heavy lifting) or slowing pace, he brought his scenes to life. Vividly.

Writer Eric Knight may have most succinctly described this particular aspect of Howard’s power in an article on Solomon Kane:

“’Wings of the Night’ features a marathon running fight through ruin, countryside, and even air that only a team of computer animators with a sixty-million dollar budget and the latest rendering technology (or a single Texan from Cross Plains hammering the story out with worn typewriter ribbon) could bring properly to life.”

Howard was only 30 when he died in 1936, meaning the bulk of his best prose — and there was a lot of it — was created when he was between 25 and 30 years of age, which makes his achievements that much more astonishing. Bram Stoker, Ian Fleming, and Arthur Conan Doyle created characters who are now rooted firmly in our popular imagination. Edgar Rice Burroughs did the same with Tarzan, and anyone who digs even a little further into his work knows John Carter is an also ran. Howard’s Conan, too, has achieved popular recognition, but there is much more to Howard than the dull barbarian depicted in the movies, one which bears but passing resemblance to the character from the stories. There was King Kull, and Solomon Kane, and Bran Mak Morn, and El Borak, and more obscure characters like James Allison, Steve Costigan, and one of my personal favorites, Turlogh Dubh O’Brien. The deeper you dig into Howard’s canon, the more treasures you find. Some of my most favorite stories are his historicals, never as popular among readers perhaps because there are so few serial characters among them, or perhaps because there are few fantastic elements within. The action and pace and all else is there, along with some of his very finest prose and plotting.

I didn’t really discover Howard until nearly 20 years ago, when I decided that if I was serious about writing fantasy I needed to explore its roots and understand where it came from. Oh, I’d seen Conan on the bookshelves and on comic book covers, but the endless rows of pastiche Conan and the fellow who was frequently running around in a loincloth on those covers didn’t much interest me. I incorrectly assumed it was all rubbish.

I didn’t really discover Howard until nearly 20 years ago, when I decided that if I was serious about writing fantasy I needed to explore its roots and understand where it came from. Oh, I’d seen Conan on the bookshelves and on comic book covers, but the endless rows of pastiche Conan and the fellow who was frequently running around in a loincloth on those covers didn’t much interest me. I incorrectly assumed it was all rubbish.

Most of the pastiche IS rubbish, although I have a few favorites among that work, but more to the point, when I finally read the actual Robert E. Howard prose and not the adaptions, I found something startling. Some people were amazed that I enjoyed it so much — wasn’t it sexist? Racist? Simplistic?

Sometimes. You can’t take an author out of his time. If Howard had written with today’s political correctness in the 1930s, he couldn’t have made a living. Sure, a lot of the women are in Conan stories to be rescued (generally when Howard REALLY needed a sale), but there are strong female characters within his work, just as heroism can be found amongst many races within Howard’s stories.

Some of the plots are pretty simple, even if they are compelling, but much of Howard’s fiction has far more going on within than there would appear to be on the surface, which is part of its appeal. Mere mindless action would not have endured so long and still be capturing new fans, me among them.

You have to take Howard at his own terms, however. If you wander in expecting to find a trove of lit fiction or teenage vampire angst, or if you look with disdain upon tales of adventure, you’re apt to be disappointed. REH was ahead of his time in many ways, but he was a Texan writing for the pulp magazines in the early 1930s. Toss that in with his aforementioned youth before you take any issues with what you find in his prose.

If you’re new to Howard, where can you find him? I suggest either volume of Del Rey’s Best of Robert E. Howard books, Crimson Shadows or Grim Lands. Try four or five stories out of there and see if you don’t notice what so many of the rest of us have seen. If you don’t, well, we all have different likes and dislikes. I won’t hold it against you.

If you’re new to Howard, where can you find him? I suggest either volume of Del Rey’s Best of Robert E. Howard books, Crimson Shadows or Grim Lands. Try four or five stories out of there and see if you don’t notice what so many of the rest of us have seen. If you don’t, well, we all have different likes and dislikes. I won’t hold it against you.

But if you DO see something you like, read on, because there’s more. A lot more. Those best of volumes aren’t like greatest hits collections of bands that had one good track per disc. That’s just a choice sampling, for there wasn’t nearly enough room in those best of volumes to get all the good stuff. No, if you like what you find when you stumble into the worlds of Robert E. Howard, you’ll have plenty to read for a long while, and much to revisit.

Not a year goes by that I don’t reread at least a handful of his yarns, reveling in a narrative power that still sweeps me up so fully that I stop noticing the words and fall between them, into the story.

In truth, I cannot single out the best thing or even the three best things in Robert E. Howard’s writing, but I name him one of my three favorite writers. Here’s to you, Bob. Today we celebrate the gifts you’ve left us. I wish that I might have thanked you in person for them. Since I cannot, I cherish your stories, and raise a toast to you in appreciation.

Reprinted from Black Gate online Jan 22, 2010

January 23, 2017

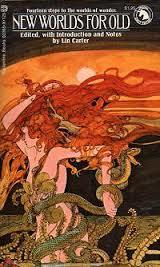

New Worlds For Old

I don’t spend a lot of time talking about the Ballantine Fantasy series anymore, but it was a great introduction to the history of fantasy fiction, and I always enjoyed Lin Carter’s introductions. Thanks to these books I became much more familiar with the grandsires of most of what we’re reading today. Some were interesting in a historical way (as in — huh, so that’s where THAT idea came from), some were curiously different from what we’re reading today, and then a handful of authors crept onto my favorites list mostly due to this series, among them Lord Dunsany.

I don’t spend a lot of time talking about the Ballantine Fantasy series anymore, but it was a great introduction to the history of fantasy fiction, and I always enjoyed Lin Carter’s introductions. Thanks to these books I became much more familiar with the grandsires of most of what we’re reading today. Some were interesting in a historical way (as in — huh, so that’s where THAT idea came from), some were curiously different from what we’re reading today, and then a handful of authors crept onto my favorites list mostly due to this series, among them Lord Dunsany.

But this particular Ballantine anthology is a favorite of mine simply because it contains, so far as I know, the only printing of Lin Carter’s very best short story, “Zingazar.” He’s in full Dunsanyian mode, imitating, as he always seemed to do, someone else’s style. But THIS time he knocks it out of the park, riffing on Dunsany’s “The Sword of Welleran” to deliver what I happen to believe is a stronger tale than the master himself, a minor sword-and-sorcery masterpiece.

Morgan Holmes and I have imagined, for years, a “best of” Lin Carter collection that would get 1-2 of his good short novels and a grab bag of his best short stories. This would definitely be right in there. Heck, I like this one so much I contributed an essay about it into a Lin Carter critical studies book. Anyway, if you’ve got this book, read the tale.

January 16, 2017

Quick Update

There’s a lot going on here, mostly because I’m in a writing frenzy. First, I changed my opinion on those Conan graphic novels I wrote about last week, and you can find the updated article here.

There’s a lot going on here, mostly because I’m in a writing frenzy. First, I changed my opinion on those Conan graphic novels I wrote about last week, and you can find the updated article here.

Second, I’ve been playing a neat game a friend got me for Christmas, a solo card game where you’re helping Robinson Crusoe survive on his island. I’ll have a detailed review eventually, but for now — two thumbs up.

Third, my friend Brad, he who gifted the above mentioned Friday card game, also gave me a copy of the new Dark Horse Conan collection, King Conan: The Conqueror. Wow, its that a good read. More details on that are to come as well.

January 9, 2017

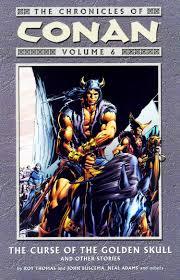

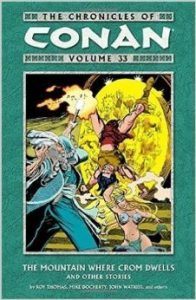

Revisiting Late Marvel Conan

I don’t often revise my web articles with aside from addressing typographical errors, but I wanted to take another crack at this particular entry, because I don’t think it was fair or well considered. Heck, I hadn’t even finished reading one of the volumes when I wrote this.

I don’t often revise my web articles with aside from addressing typographical errors, but I wanted to take another crack at this particular entry, because I don’t think it was fair or well considered. Heck, I hadn’t even finished reading one of the volumes when I wrote this.

Dark Horse has been reprinting the entire Marvel run on Conan now for multiple years. I’m a latecomer to the comic, even in reprint form, so the stories are new to me.

I read and enjoyed many of the Roy Thomas written run (volumes 1-14, although 15-17 have additional Thomas penned stories). Experimentation with reading the tales by other writers in 15-17 led me to conclude that, as promised, the non-Thomas Conan is pretty wretched, so I’ve held off reading any more until he rejoined the mag in volume 31. (I should add that I do hear good things about Priestley’s run on the Marvel Conan and will probably check one of those collections out before much longer.)

But the point of this brief post is a look at these final Thomas collections, and they’re substantially better than the ones that appeared immediately following the departure of Thomas.

Roy Thomas

I wasn’t as keen on Volume 31, which is overburdened with the presence of Red Sonya, who’s constantly grousing or ready to fight someone/thing. Maybe it’s me, but I’ve never much enjoyed the character. That said, it has a nice sword-and-sorcery vibe to it, and some of the individual issues work very nicely.

Volume 32 is pretty strong, with a number of good stories. The Shuma Gorath plot, about an evil priesthood summoning a forgotten, Lovecraftian God, is somehow more “Marvel” than Conan, but there are still some excellent sword-and-sorcery moments throughout the issue, particularly when Conan is forced to ally with an ancient and devious wizard.

Volume 33 opens with the conclusion of the Shuma Gorath arc, over two issues, and I’m sad to say it reaches an overly busy conclusion. However, once Shuma Gorath is finally over, Conan is adventuring again with only a single companion, and the tales in 33 get more and more interesting — I especially liked the last four issues, which are freely adapting Clifford Ball’s “The Thief of Forthe” and a Leonard Carpenter TOR Conan novel. Those issues are right up there with some of the best Roy Thomas Conan from any previous issue. As a matter of fact, since the conclusion of the arc isn’t in this volume, I’m REALLY looking forward to seeing how volume 34 finishes it up.

Volume 33 opens with the conclusion of the Shuma Gorath arc, over two issues, and I’m sad to say it reaches an overly busy conclusion. However, once Shuma Gorath is finally over, Conan is adventuring again with only a single companion, and the tales in 33 get more and more interesting — I especially liked the last four issues, which are freely adapting Clifford Ball’s “The Thief of Forthe” and a Leonard Carpenter TOR Conan novel. Those issues are right up there with some of the best Roy Thomas Conan from any previous issue. As a matter of fact, since the conclusion of the arc isn’t in this volume, I’m REALLY looking forward to seeing how volume 34 finishes it up.

Volume 34 will be the last to see print, and it’s going to be bittersweet. Admittedly I haven’t enjoyed some of these later stories as much as earlier ones, but even an average Roy Thomas Conan story is head and shoulder above almost any other Conan pastiche, and there’s still some grand storytelling going on here. The guy GETS Conan as a character and respects Robert E. Howard’s work, and is an excellent plotter/writer/creator of dialogue. We’re very, very lucky that he helmed the Marvel Conan franchise for so long. As a matter of fact I can’t help wishing there was more Conan from him. The twelve issues he did for the Dark Horse comic line are among my very favorites from the whole new Conan run, and, as a matter of fact, were so good they’re what got me to finally take a look at his Marvel Conan work.

Fortunately, I still have a number of unread Savage Sword of Conan collections left on the shelves. It’s nice to have treasures yet to explore. I know from experience that there are a handful of Savage Sword writers besides Thomas who can pen a good tale–and, as a final treat, I left some of the RT issues unread so I could enjoy them later, and those will have Buscema artwork to boot.

Late Marvel Conan

Dark Horse has been reprinting the entire Marvel run on Conan now for multiple years. I’m a latecomer to the comic, even in reprint form, so the stories are new to me.

Dark Horse has been reprinting the entire Marvel run on Conan now for multiple years. I’m a latecomer to the comic, even in reprint form, so the stories are new to me.

I read and enjoyed many of the Roy Thomas written run (volumes 1-14, although 15-17 have additional Thomas penned stories). Experimentation with reading the tales by other writers in 15-17 led me to conclude that, as promised, the non-Thomas Conan is pretty wretched, so I’ve held off reading any more until he rejoined the mag in volume 31. (I should add that I do hear good things about Priestley’s run on the Marvel Conan and will probably check one of those collections out before much longer.)

But the point of this brief post is a look at these final Thomas collections. They’re certainly better than the ones that appeared immediately following the departure of Thomas. But on the whole I haven’t enjoyed these three collections nearly as well.

Roy Thomas

Volume 31 has a few good moments but is overburdened with the presence of Red Sonya, who’s constantly grousing or ready to fight someone/thing. Maybe it’s me, but I’ve never much enjoyed the character. Volume 32 is the best of the lot, with a couple of good stories, although it’s burdened with the ongoing “Shuma Gorath” plot, which reaches a overly busy conclusion in Volume 33. Once Shuma Gorath is finally over, Conan is adventuring again with only a single companion, and the tales in 33 get more interesting — although I’ve yet to read one that’s really blown my socks off. I have two more left to go in the collection.

Volume 34 will be the last to see print, and I’m sure I’ll read it, because even an average Roy Thomas Conan story is better than most Conan pastiche. But I find myself missing the glory days. Fortunately, I still have a number of unread Savage Sword of Conan left on the shelves. It’s nice to have treasures left to explore. And I know from experience that there are a handful of Savage Sword writers besides Thomas who can pen a good tale.

January 6, 2017

Computer Woes and Happy Holidays

My own computer’s in the shop, which makes posting to the web site a little problematic. Apparently some MacBook Pros, mine among them, develop keyboard malfunctions where bit by bit more and more of the keys randomly fail to respond. In my case it started with the n key, then moved onto the c and the b keys and the “command” key. I could get any of them to work if I struck them nine or ten times, but once that began to happen with multiple keys typing became one long act of frustration.

My own computer’s in the shop, which makes posting to the web site a little problematic. Apparently some MacBook Pros, mine among them, develop keyboard malfunctions where bit by bit more and more of the keys randomly fail to respond. In my case it started with the n key, then moved onto the c and the b keys and the “command” key. I could get any of them to work if I struck them nine or ten times, but once that began to happen with multiple keys typing became one long act of frustration.

Until I get my faithful laptop back I’ve been using my old Dell to write on. The screen attachment is halfway pulled out of the laptop and it has to remain plugged in at all times or it dies instantly — and sometimes while you’re typing it randomly jumps lines — but it’s certainly better than nothing at all and even in this state is still an astonishing piece of technology that would have blown my mind when I was a kid.

The holidays have been nice around here. I wish I could have had more time to relax, but the novel revision is still looming over my shoulder so I’ve only managed a few days off. I would have liked a good 7 days in a row, but I’ve never managed more than 2. Still, in the evenings I’ve been playing boardgames with the family, primarily crayon rail games like Iron Dragon and Martian Rails (I mentioned both games on the site before, in 2013). As usual I’ve lost to the wife, who’s a genius, and a genius at these games in particular. In the past I’ve managed some victories with Martian Rails, but this time I came in dead last. My son’s got the games figured out now and is playing like a champ, apparently having picked up on some of the wife’s strategies that have eluded me through the years.

The holidays have been nice around here. I wish I could have had more time to relax, but the novel revision is still looming over my shoulder so I’ve only managed a few days off. I would have liked a good 7 days in a row, but I’ve never managed more than 2. Still, in the evenings I’ve been playing boardgames with the family, primarily crayon rail games like Iron Dragon and Martian Rails (I mentioned both games on the site before, in 2013). As usual I’ve lost to the wife, who’s a genius, and a genius at these games in particular. In the past I’ve managed some victories with Martian Rails, but this time I came in dead last. My son’s got the games figured out now and is playing like a champ, apparently having picked up on some of the wife’s strategies that have eluded me through the years.

I pulled out Hornet Leader a little before Christmas and finally finished a long campaign last night. I’ve had to keep it on a handy reinforced length of cardboard originally used for packing a wall mount television. The cardboard is supported on its underside by two styrofoam struts so that it doesn’t bend, which makes it the near perfect portable platform for a game with lots of counters and cards. It would be even better if it had ridges, but I’m still pretty happy with it. So long as I don’t trip over the dog, I can carry the game on its cardboard “table” back to my office every night after I play a mission and leave the counters on the cards. So much easier than having to set the game back up every evening to play a new mission. Oh, and on Black Gate the other day I finally posted a lengthy review of HL which explains why I enjoy it.

I pulled out Hornet Leader a little before Christmas and finally finished a long campaign last night. I’ve had to keep it on a handy reinforced length of cardboard originally used for packing a wall mount television. The cardboard is supported on its underside by two styrofoam struts so that it doesn’t bend, which makes it the near perfect portable platform for a game with lots of counters and cards. It would be even better if it had ridges, but I’m still pretty happy with it. So long as I don’t trip over the dog, I can carry the game on its cardboard “table” back to my office every night after I play a mission and leave the counters on the cards. So much easier than having to set the game back up every evening to play a new mission. Oh, and on Black Gate the other day I finally posted a lengthy review of HL which explains why I enjoy it.

My son’s heading back to college Sunday, alas. He’s doing great there, but I sure miss him when he’s not around. He spent a lot of time over the holiday applying for summer internships, which will be great for his career but will mean he won’t be around this summer if he gets them. So, good and bad. Apart from Pictionary my daughter hasn’t been interested in joining any of our board games. I’m going to try to lure her into a game of Pandemic, which we’ve purchased this summer but not yet gotten to the table.

I know I savored the time with them both when they were younger. I even remember patting myself on the back for doing so. It was simpler for me to be with them than it is for a lot of parents because for a good chunk of that time I was a freelance editor working from home. And yet, with one a sophomore in college and the other a junior in high school I find myself astonished at how fast it has gone. I want to grab more time with them both, somehow. As I was looking up earlier posts on Martian Rails I saw that I’d written my first mention of it on the blog back in July of 2013. Even three years ago it felt like there was a lot more time that lay before us under the same roof. It feels like we’re coming to the end.

January 3, 2017

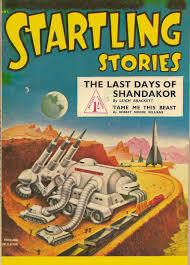

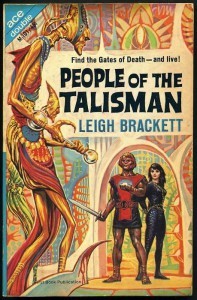

Leigh Brackett: “The Last Days of Shandakor”

Bill Ward and I had been meaning to get back to our re-read series at some point last year, but we both got busy. And so we decided to start the new year with a read of one of my favorite Leigh Brackett stories, “The Last Days of Shandakor.” It was the third read for me, but Bill was new to the tale, and so was Fletcher Vredenburgh, who we invited aboard.

Bill Ward and I had been meaning to get back to our re-read series at some point last year, but we both got busy. And so we decided to start the new year with a read of one of my favorite Leigh Brackett stories, “The Last Days of Shandakor.” It was the third read for me, but Bill was new to the tale, and so was Fletcher Vredenburgh, who we invited aboard.

Brackett, of course, was an adventure fiction pioneer and one of the main reasons that the pulp Planet Stories is remembered today (although this particular tale originally appeared in the magazine Startling Stories). She was writing grand space opera/sword-and-planet/science fiction/fantasy back in the ’50s and ’60s and continued doing so right until the end of her life, and sometimes it seems like that footnote (that she completed a first draft of The Empire Strikes Back) has overshadowed everything else she did. It shouldn’t, though. She was writing about complex characters who could easily have rubbed shoulders with Han Solo or Mal Reynolds decades before those two were ever invented. All of her tales are infused with a real hardboiled grit and… well, heck, maybe I should stop introducing and just get onto the discussion.

Howard: As always, I’m caught by that first paragraph. Someday I hope to write openings so finely, but I may hope in vain. Consider it again: “He came alone into the wineshop, wrapped in a dark red cloak with the cowl drawn over his head. He stood for a moment in the doorway and one of the slim dark predatory women who live in those places went to him, with a silvery chiming from the little bells that were almost all she wore.” It so perfectly paints the images with only a few words, complete with exotic atmosphere and the suggestion of mystery. Who is that stranger and why is he looking around? And that woman — a lesser writer would have mentioned her curves or exposed skin. Brackett evokes her dangerous, beguiling sensuality altogether more skillfully.

Howard: As always, I’m caught by that first paragraph. Someday I hope to write openings so finely, but I may hope in vain. Consider it again: “He came alone into the wineshop, wrapped in a dark red cloak with the cowl drawn over his head. He stood for a moment in the doorway and one of the slim dark predatory women who live in those places went to him, with a silvery chiming from the little bells that were almost all she wore.” It so perfectly paints the images with only a few words, complete with exotic atmosphere and the suggestion of mystery. Who is that stranger and why is he looking around? And that woman — a lesser writer would have mentioned her curves or exposed skin. Brackett evokes her dangerous, beguiling sensuality altogether more skillfully.

Fletcher: Brackett is someone who has been recommended to me in the strongest terms for years now. Except for her post-apocalypse novel, The Long Tomorrow, I have read nothing else by her until now. Even before I finished “The Last Days of Shandakor,” I knew I was reading something very good.

You’ve said almost exactly what I’d planned to say about those first few paragraphs. I even underlined the “slim dark predatory” bit myself. With prose like that, Brackett engulfs the reader with a sense of danger and mystery right away. As the stranger, whom people “simply refused to see,” weaves his way through the crowd, I was as captivated as the yet unnamed narrator.

Bill: Interesting how a room full of people not looking at someone has the opposite effect on the audience — we look! I think the opening of “Shandakor” is a terrific example of the power of a short story to accelerate from a dead stop to full speed ahead in just a few lines, and Brackett sure seems to be a natural at it. By the time our narrator is talking to the mysterious stranger, I realized I was already hooked.

Bill: Interesting how a room full of people not looking at someone has the opposite effect on the audience — we look! I think the opening of “Shandakor” is a terrific example of the power of a short story to accelerate from a dead stop to full speed ahead in just a few lines, and Brackett sure seems to be a natural at it. By the time our narrator is talking to the mysterious stranger, I realized I was already hooked.

Some of these stand out elements remind me of Robert E. Howard’s strengths, though Brackett adds a spareness of phrase more on the order of the hardboiled school. But her evocation of the exotica of Mars is straight from the REH playbook with words like “Barrakesh” and “Shunni” being close enough to our real world lexicon of places and people to suggest their meaning to the audience without ever actually needing to go into detail. Combine that with precise and active word choices, and a compelling central premise and you’ve got an opener that grabs you completely — even in the absence of a compelling or interesting protagonist. I suspect a lot of critical readers would fault this story — and much of pulp fiction — for its narrator/protagonist John Ross, but I think you could also argue that Brackett keeping the narrator almost as mysterious to us as the other elements of the piece really underscores several of the key elements of the story. What do you guys think about Ross?

Howard: Ross serves as an everyman. We can relate to him and even, come the end, despise him a little, just as he despises himself, but he mostly serves as our vehicle to observe Shandakor’s mystery and people. He’s reasonably clever, fairly competent, learned, and fears and loves in all the right places for all the proper reasons. He offers no surprises, but then, as I wrote, the story’s not really about him.

Howard: Ross serves as an everyman. We can relate to him and even, come the end, despise him a little, just as he despises himself, but he mostly serves as our vehicle to observe Shandakor’s mystery and people. He’s reasonably clever, fairly competent, learned, and fears and loves in all the right places for all the proper reasons. He offers no surprises, but then, as I wrote, the story’s not really about him.

I also have to point out that I think you’re definitely on to something with her hardboiled style. REH could do that himself, of course, but it’s more marked with Brackett, who spent long years working with mysteries. I’m not sure that there’s anyone of her era that quite brought that same style to space opera/sword-and-planet/science fiction (whatever it was, quite, that she was writing that was combination of all of those with fantasy thrown in besides).

Fletcher: The only real trait of Ross’ we learn about is his ambition for a university chair. Without any real nuance to him, he comes across as driven and somewhat selfish. Both those traits point toward some of the story’s themes as well as its sorrowful ending. Essentially, though, he’s a blank, left to be filled in by the reader and serve as our eyes to take in the wonders of Shandakor and the melancholy of its last days.

Which brings me to the real heart of the story. As terrific as Brackett’s pulp-style setup and narrative are, it’s the elegiac nature of the story that effected me most, as I imagine she intended. Once he enters the city, the story becomes a death watch. We are given visions of Shandakor’s glorious past, but it’s all illusion provided by wonderful pulp-style superscience. Then, we are forced to watch its final moments, but only after suffering through a prolonged and steady march towards oblivion as the city’s supplies dwindle to nothing.

Which brings me to the real heart of the story. As terrific as Brackett’s pulp-style setup and narrative are, it’s the elegiac nature of the story that effected me most, as I imagine she intended. Once he enters the city, the story becomes a death watch. We are given visions of Shandakor’s glorious past, but it’s all illusion provided by wonderful pulp-style superscience. Then, we are forced to watch its final moments, but only after suffering through a prolonged and steady march towards oblivion as the city’s supplies dwindle to nothing.

Like the best of REH or Moore, Brackett’s writing more than “mere” pulp, but relying on its tropes and bending them to her will. It’s fascinating to study and try to understand how she did it.

Bill: And wouldn’t you just love to give this story to someone that thinks pulp is nothing but plotlines and punch-ups? There is hardly an action scene in the entire tale, and what is there is over and done with in a heartbeat. Instead we get an almost parable-like tale about a dying civilization living out its final days in an illusion of the past — an illusion our protagonist destroys out of ignorance and greed. Here is where keeping the character as vague as he is really paid off — he is just relatable enough that the audience ends up somewhat complicit in his crime, because we ourselves would like to escape the city and save the life of Ross’s young Shandakorian guide. It’s only after he destroys the crystals that give life to the “memories of the stones” that we fully comprehend that Ross’s ambition and vanity makes him little better than the barbarians that besiege the city though, unlike them, he does comes to understand just what has been lost.

Howard: Brackett has an amazing talent for evoking lost grandeur and fading glory. I don’t know that any fantastic Mars has ever been quite as lonely and stunning as hers, although perhaps in the hands of her close friend Ray Bradbury there’s a similar aesthetic.

Howard: Brackett has an amazing talent for evoking lost grandeur and fading glory. I don’t know that any fantastic Mars has ever been quite as lonely and stunning as hers, although perhaps in the hands of her close friend Ray Bradbury there’s a similar aesthetic.

Do either of you have favorite moments? I think the most powerful for me may be when Duani refused him — although that heart rending conclusion is a close second. Did you have any favorite parts? And what did you think of Duani?

Fletcher: The very end, when Ross, years after the fall of Shandakor, is still filled with despair over what he did and all his success is but a mouthful of ashes, was my “favorite” part of the story. I use quotes because it’s one hard, bitter-tasting ending that I won’t soon forget. It’s brilliant and haunting.

I love Duani and what Brackett does with what could have been a thin, stock love-interest character. On the one hand, she really is the fairy tale princess Ross sees her as, but a distinctly alien, inhuman woman on the other. As much as she seems to love Ross, she treats him with the kind condescension of her people toward humans to the very end. Her embrace of Shandakor and its peoples’ fate seems downright alien as well.

I’m glad you brought up Bradbury. I was reminded of him as soon as I understood what was going on here. As much as I like Bradbury, though, I think I’m more drawn to Brackett’s less deliberately literary style.

Bill: Bradbury does come to mind, which only makes sense when you consider that his Martian stories are almost all concerned with loss, though I suspect the comparison wouldn’t really suggest itself when reading Brackett’s older Mars stories since Bradbury never wrote adventure fiction.

Howard: Let me jump in here with an odd fact — Bradbury did write adventure fiction, and in collaboration with Leigh Brackett herself. Brackett wrote about half of the story “Lorelei of the Red Mist” and then got asked to go to Hollywood to help write the screenplay of The Big Sleep (with William Faulkner, no less) so she turned the text over to Bradbury, who wrote the last ten thousand words with nary an outline or direction. And it’s a damned good adventure tale.

Howard: Let me jump in here with an odd fact — Bradbury did write adventure fiction, and in collaboration with Leigh Brackett herself. Brackett wrote about half of the story “Lorelei of the Red Mist” and then got asked to go to Hollywood to help write the screenplay of The Big Sleep (with William Faulkner, no less) so she turned the text over to Bradbury, who wrote the last ten thousand words with nary an outline or direction. And it’s a damned good adventure tale.

That sense of the lost and forgotten and the end of things, with its atmosphere of hardboiled grit crossed with fantastic exoticism, is present in nearly every one of Brackett’s Mars and Venus stories, and some others besides (like “The Veil of Astellar” which goes down even smoother when you read it if you imagine the voice of Humphrey Bogart as narrator.)

Sorry — back to you, Bill!

Bill: I think my favorite part, too, is the end. Specifically Ross’s selection of just one piece of the treasure of Shandakor — a small figure of an alien girl. It’s the proof that Ross has grown, that he isn’t an anti-hero. The barbarians treated him with awe when they found him, and in a slightly different story Ross could have ruled the city, kept the crystals and their record of the past, truly achieved some godlike dream of his. But this Ross destroyed the crystals — literally erased the thing he wanted more than anything — in an attempt to save Duani, and then begged to be allowed to die with her. I don’t know if you could say he loved her, certainly they were incapable of loving each other or, perhaps, whatever they felt for one another would never be enough to change the reality of their situation. But that is what redeems Ross in the end — though it’s also what kills Shandakor.

Bill: I think my favorite part, too, is the end. Specifically Ross’s selection of just one piece of the treasure of Shandakor — a small figure of an alien girl. It’s the proof that Ross has grown, that he isn’t an anti-hero. The barbarians treated him with awe when they found him, and in a slightly different story Ross could have ruled the city, kept the crystals and their record of the past, truly achieved some godlike dream of his. But this Ross destroyed the crystals — literally erased the thing he wanted more than anything — in an attempt to save Duani, and then begged to be allowed to die with her. I don’t know if you could say he loved her, certainly they were incapable of loving each other or, perhaps, whatever they felt for one another would never be enough to change the reality of their situation. But that is what redeems Ross in the end — though it’s also what kills Shandakor.

Duani, I think, is the most important character in the story. Of course we absolutely need her for the climax to happen — she’s the reason Ross is in charge of the memory crystals, and also his motivation for destroying the crystals rather than just waiting for the city to die. I’d say, though, she’s also a stand in for her entire people. When we are introduced to her, she is childlike and innocent. Ross doesn’t even think of her as anything but a child until he’s spent time with her. She could have been a nubile alien temptress that decided to keep Ross as a plaything, or even a mature woman that protected him in a more maternal way, but instead she is a juvenile who has grown of age at a time when her people are already near-death, and who has no peers to pair up with, not so much as a friend. She might even be the last child of Shandakor.

Howard: Nicely said, and I thought your observation about his growth as a character was brilliant.

Howard: Nicely said, and I thought your observation about his growth as a character was brilliant.

Ross thinks of Duani as a child until he’s spent time with her. I wonder how old she truly is? She looks very young, but I had the sense that she was older than her appearance. Certainly she has a maturity of presence and manner. And I’m pretty sure that Ross is making love with her between the scene breaks, especially the one after he picks her up and carries her away. By then she has just begun to look upon Ross as a woman in love might… until he arranges to destroy the illusion of their city.

Bill: The leader of the city tells Ross that the Shandakorians were able to create the great things of the past because they embraced reason. He goes on to respond to Ross’s assertion that Earthmen, too, have reason by saying that humans assume reason operates automatically, and so they mistakenly use it to justify all the emotional and superstitious decisions they make. Ross is an anthropologist who never makes a discovery in the story without considering how it will further his career and yet who, when he has the greatest discovery ever made on Mars in his hands, destroys it. He was fascinated by the alien stranger and he becomes infatuated with the alien girl, but both make it clear that their world is not for him. He ends up killing both (though Duani’s murder is a spiritual one) because he will not turn back where he is not wanted, where he doesn’t and cannot belong.

He isn’t, however, an unsympathetic character, because we share his faults. Even though Ross is essentially given everything he was ostensibly looking for (a complete and vivid record of a lost people), it isn’t enough. Certainly the context of his imprisonment mitigates his actions to a large extent — he is, after all, kept in chains by aliens while a barbarian horde waits just outside to sack the city he is in — and I think that is a smart play by Brackett to back him into a corner and, thus, keep the audience on his side, otherwise we wouldn’t be sharing in the sense of loss at the end of the piece, but condemning the protagonist. And I think that’s what’s really effective about this story — plenty of other stories evoke the exoticism of lost civilizations or the doom of dying races, but here we have one where the protagonist is complicit in the loss without him being some sort of amoral anti-hero like Cugel the Clever, but a capable scientist, a basically decent fellow, but one who confuses his own desires for reason.

Leigh Brackett and Edmund Hamilton

Fletcher: I don’t really have much to say after that, Bill. I think you’ve dug deep into all the important parts of the story. I agree that Brackett was very sharp to keep us on Ross’ side and the ways in which she did it. Ross brings on the end of Shandakor and its people from the best of intentions. I remained sympathetic to him, even as his actions infuriated me (it’s obvious what Duani’s reaction will be). He only accelerated the eventual end and nothing he could have done would have averted it.

Ross’ actions lead me to one last thing. In a broad sense, it reminded me of Clifford Simak’s City, also written in the shadow of atomic war after WWII, when he had lost faith in humanity. Like Simak, Brackett seems to have a dark and resigned view of us. Ross is told human reason teaches “no difference between fact and falsehood” and we fight “the bloodiest wars for the merest whim.” Ross’ furious reaction to these charges as well as his final, misguided act, only seem to prove the charges. Ross is definitely a different sort of protagonist than the take-charge Campbellian hero.

I’m so glad you suggested this, Howard. This conversation has been great fun and I’m glad to have been part of it. That I’ve reached 50 without having read any of Brackett’s short stories seems unbelievable. On the other hand, I do have a ton of new-to-me stories to look forward to (as well as the Skaith trilogy). Even with a TBR stack that seems to have reached infinite proportions, I’m about to start a Brackett binge.

Bill: Fun indeed. And you’re not alone in not having read Brackett, I’ve barely scratched the surface. But between the Baen ebooks and what I have of her from the Paizo Planet Stories line, it looks like I’ve got plenty to explore!

Howard: She was a great writer. Alas, it’s a finite resource, and you’ll quickly reach its end. I think you’ll find that the Skaith novels are grand in their way but that they have a feel of “after glow” to them in that while they’re good pulp adventures they’re not quite as compelling overall as the very best of her short stories. They feature Eric John Stark, of course, her one serial character, who’s also found in three short stories, one of which, “Enchantress of Venus,” is among my favorite adventure tales of all time.

Howard: She was a great writer. Alas, it’s a finite resource, and you’ll quickly reach its end. I think you’ll find that the Skaith novels are grand in their way but that they have a feel of “after glow” to them in that while they’re good pulp adventures they’re not quite as compelling overall as the very best of her short stories. They feature Eric John Stark, of course, her one serial character, who’s also found in three short stories, one of which, “Enchantress of Venus,” is among my favorite adventure tales of all time.

December 28, 2016

On Writing and Speed

Writing can be a struggle. I think we have to admit that. And I have to admit to myself that some things in this profession are beyond my control. It may be that I’ll never be quite as fast as I want to be, and it may be that I’ll always have to spend long days in rewrite, no matter how carefully I outline.

Writing can be a struggle. I think we have to admit that. And I have to admit to myself that some things in this profession are beyond my control. It may be that I’ll never be quite as fast as I want to be, and it may be that I’ll always have to spend long days in rewrite, no matter how carefully I outline.

I have scads and scads of ideas and stories I’m excited about, but sometimes I worry that I’ll never get to them because it takes so long to get one right. And I keep thinking that with practice I’ll get faster so I can write more stories, but there’s a give and take with energy levels. I may want to write a short story in my spare time, but many evenings when I have “extra time” I don’t have much extra energy.

It seems like the writing is getting better — thank God for that — but I’m not sure that speed is improving so very much. Don’t get me wrong, I’ll keep trying on that score. But I’m starting to wonder if maybe I shouldn’t shift my desires towards goals that are more reasonable for me. If speed isn’t ever going to be the result, maybe the best thing is to take more time with the original draft so that less time is required during revision.

I’ll think it over, try some things out, and let you know how it goes.

Howard Andrew Jones's Blog

- Howard Andrew Jones's profile

- 368 followers