Winn Collier's Blog, page 44

March 1, 2012

Confession and Desire

Miska and I have a running joke that if I were ever to go completely unhinged and do something stuipd like have an affair, I'd manage to keep it under wraps for about 19 seconds. When guilt hits, I go blabbing. When I was in second grade, I went running to my mom, in tears, confessing the evil I'd done. "What happened, Winn?" my mom asked. "I cursed," I answered. "I used the word upchuck." How my mom held back the laughter, I'll never know.

Recently, Miska, in a strange turn of conversation, was forced to cough up that she had snooped around to find out what gifts I had bought her last Christmas. She logged into my email. She poked around my Amazon account. She didn't happen upon her information; she executed MI5 style tactics. I'm surprised she didn't waterboard the boys to make them talk. I like surprises, so I was irritated by her admission. More, though, I was impressed. Given my psyche, I can't fathom engaing in that chicanery and then just tooling along as if nothing happened.

My confessive compulsion is extreme. However, the act of confession, of saying the truth about something, is an immense gift. We tend to think of "confessing our sins" as necessary bookkeeping, knocking off a litany of all our inappropriate behavior so that God will then knock these same items off his list of things to smack us for. Confession, I believe, is closer to the moment when I stop playing coy with Miska and admit I really crave her touch. Or when Seth falls flat on the hard ground, spread eagle with his face smashed into pavement — then amid tears and pain makes it plain he wants nothing but his dad to gather him up and hold him tight. Of course, there's nothing I want in that moment more than to rush to his side and pour love over his hurt.

In Scripture, confessing our sins is simply the way of speaking the truth to God so that we can stop living in the far away corner and get on receiving love. Confessing our sins isn't the point. Forgiveness is the point. Love and friendship is the point. Living the good life – that's the thing God's working in all this. Lent is the season of clearing the air, of confessing what is, the season of getting on with the good life.

Confession is about healing pouring into our cracked places, our alone places. Confession is about coming clean with the fact that, left to our lonesome, we are lost – but also owning the fact that we dare to long for much, much more. To confess is to say the truth about ourselves and our place and our desire. Confessing how we've trespassed the commandments is a humling thing. Confessing how we've abandoned good and true desires — that's a terrifying thing.

Orthodox priests speak this prayer after private confession:

May God who pardoned David through Nathan the prophet when he confessed his sins, and Peter weeping bitterly for his denial, and the sinful woman weeping at his feet, and the publican and the prodigal son, may the same God forgive you all things, through me a sinner, both in this world and in the world to come, and set you uncondemned before his terrible Judgment seat. Having no further care for the sin which you have confessed, depart in peace.

Clear the air. Say it clean. Then depart, without a care. In peace.

February 27, 2012

Kilts and Creeds

I don't know much about my genealogy. I wish our kin had one of those large cracked leather Bibles with a family tree printed in the front, the kind that goes back seven or eight generations. I know that on my mother's side, if you trace far enough, we'd find our way to a Cherokee Indian Chief. Our family name was Lightfoot. When I'm feeling low about my station in life, I remember I'm Cherokee royalty. On my dad's side, there's Scottish blood. I don't know how my ancestors arrived here – or why. But perhaps this explains my enduring love of the Scottish brogue, Sean Connery and kilts.

There's a fellow in the local outdoor gear shop who wears a red, black and green kilt to work. He has long, black hair tied in a man-tail. He's got the leather boots and the lean, muscular frame to go with it. I keep expecting to find him with an axe slung over his shoulder. It's quite an experience to see a fellow in a skirt and think he's the manliest thing you've seen in a long while. I've never owned a kilt or an axe, but I'm happy to say that those who do are my people.

The stories that have led us to this life, this land, are not merely biographical detail. They are the threads that have weaved us into being. We belong to a history. We didn't create it. We didn't choose it. Yet here we are, chosen and crafted by a story that was before us, a story that has invited us in.

This is what the church's creeds offer. The Apostles' Creed is a story. If we read the Creed first as a list of theological facts, we may get the gist, but we'll entirely miss the juice. The Creed is the story of God and God's action for us, toward us. The Creed narrates the drama, tugs us through love and ruin, through hell and back. And with each movement, the story reminds us of our history and reminds us of who we are, lest we forget. We are the ones loved by God, loved so much that God refuses to forget us. This story has chosen us. This story has made us. If it tells us anything at all, the Creed tells us we are part of a history and a people: God's history, God's people. We are not (and never have been) alone.

And the Creed is also a prayer; it ends with amen. Good stories are always a sort of prayer. They carry us through all the beauty and the rubble to the place of truth. When a good story has worked it's way in us, we have little to say except Amen. May it be so.

February 23, 2012

A Walk Across the Sun

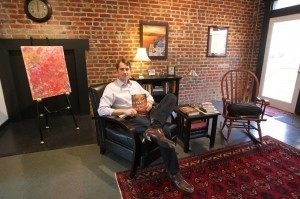

I've asked a few friends to stop by for a house-warming party in my new digs. Corban Addison has just released his first novel A Walk Across the Sun, set in india and following several characters intersection with the seedy world of human trafficking. The book's catching steam; it's been pushed by John Grisham and Oprah's O Magazine. In a flat world where we demand everything be efficient and have obvious (and immediate) utilitarian purpose, many of us insist that the work itself offers goodness to the world – writing need not be justified by accomplishing some other purpose or added agenda. However, sometimes we ride that mule too far, to the point that our writing becomes selfish and myopic. In Corban's debut novel, he has written something that takes the story seriously, on its own terms – but he also has a message he wants to give away. This is not easy to do.

This part of the party's going to be a conversation around the table.

Why writing, Corban? Why do you find yourself needing to tell stories?

Since I was fifteen years old and starting to spread my wings in an adult world, writing has been my outlet, the preferred channel for my thoughts. When I was a kid, I used to write essays and reflections on anything and everything, work on them tirelessly until I felt I had perfected every word, and then stuff them away in a file on my computer, never to be read by anyone. At the same time, I read voraciously and preferred fiction. Story was a form of travel for me. It peeled back the skin of the world and gave me a glimpse of humanity as it looks under the hood. I've always been conscious of truth, and I've always loved to learn. Long before I ever thought about the power of story, I responded to that power by devouring stories and allowing them to frame my vision of the world. At some point, these two currents (my impulse to write and to consume stories) merged into a singular dream: to write a story. As soon as I tried my hand at it, I fell in love with it. And away I went, down the Rabbit Hole. For years I wrote stories as I had written essays, spending countless hours refining them, only to learn that no one wanted to publish them. But the dream only grew stronger as the pile of rejections mounted. That was a training ground. I learned how to write by trying and failing and trying again. All along I believed I would find a story with wings. Ironically, when it happened, it was the story that found me. The idea for A Walk Across the Sun was my wife's before it was mine.

You've written a good story that also has something of an agenda – you want people to think long and hard at the issue of sex trafficking, hoping to contribute to another abolition of slavery. Did you think much about the interplay between letting the story be the driver and letting the issue be the driver?

When I set out to write A Walk Across the Sun, I knew it would never work unless it could stand alone as a compelling work of fiction. The story had to sing, or it would flop. That said, my objective in writing a novel about the global trade in human beings was to confront the reader with a reality that many people find hard to believe. I wanted to do more than describe the problem. I wanted to give readers a first-class trip through the trafficking pipeline. I wanted to reveal the many dimensions of the trade and to leave readers with the strong sense that all is not lost, that hope is real and that all of us can engage in the fight for justice. Bringing the two strands together was a labor of love and editing. There were times in early drafts of the manuscript where I fell into the didactic trap, overplaying my hand as an advocate. Eventually, however, with the help of some fine editors, I was able to submerge the facts about trafficking into the narrative, leaving the story to drive the book and allowing the issue to emerge organically in the consciousness of the reader through the experience of reading the story.

Colum McCann says, "I believe fiction can capture the moment when the thorn enters the skin." Where do those words take you?

Story has been around as long as communication itself. It transcends every barrier that divides us as human beings, and it compels us in a way that nothing else can. In a very real sense, story is the universal language. In my mind, the reason for this is simple. Story is the framework of our existence. All of us are living a story, so all of us are interested in stories. What makes fiction such a powerful medium is that it allows the writer to transport the reader to places within a particular story that would be missed in a purely factual account. There are moments in life that have profound significance, yet the clock doesn't slow down to allow us to dissect them, ponder them, suck the marrow from their bones, and live inside the transformation. In fiction, the clock can slow down or speed up. One scene, one moment, can occupy pages or a single sentence. A story can open a window on the world that does not exist in the four dimensions of space-time. There is great irony in this: Fiction offers perspectives on reality that reality itself cannot afford.

This year, I'm feeling tugged into new places of generosity, as a man, a dad and husband, a writer and pastor. I'm going to give you a prompt; just tell me whatever comes to your mind. Here goes: write with generosity

One of the saddest facts of modern art is the all-too-common divorce between the artist and the audience. So many artists these days pride themselves on creating art for themselves, not for the people who will view it, read it, and ponder it. To me, writing generously is writing with the audience in mind–not in a disembodied sense, but in a very real, very particular sense. When I was writing A Walk Across the Sun, I wanted to create a story that would reach the broadest possible audience, from the seventeen-year-old girl who spends her afternoons devouring books to the eighty-year-old grandmother who puts down her knitting and picks up a novel. In crafting the plot and the characters, I made very intentional choices about what I would include and what I would not include, how I would describe certain things, especially difficult things like sexual violence and the trafficking of children. I knew that my readers would be real people, and I wanted to meet them in the reality of their lives and give them a story they would love and a story that would open their eyes to the world around them in a new way.

image: daily progress

February 21, 2012

Lenten Possibilities

Some days

one needs to hide

from possibility

{Kooser and Harrison}

Recently, Wyatt pronounced a liberating confession. "Dad, I'm going to start watching TV instead of Netflix."

"Why?" I asked.

"Well, Netflix has a 1,000 choices, and I can never choose. But the TV only offers three choices. That's better."

We were not made for vast infinity. We were made to be creatures with limitations. Some resist this axiom and pursue a dogged determination to contravene the fact that our body is sagging, our energy fleeting, our years narrowing. What are midlife crises other than a panicked effort to wrench every conceivable possibility from the past and ride it wildly into the present? I speak as a man who has moved into that mid-life shadowland.

But it is a grace to know our place, to know that we are not defined by our possibilities, whether missed or exploited. We are defined by the one who has loved us – and by the love that, having settled into our heart, eeks out meagerly and lavishly to the ones we are uniquely able to love. To live with perpetual options is to never settle into gritty and particular living, into gritty and particular love. Only God is able to truly love the whole world. And we are not God.

To try to live everywhere is to never truly live anywhere. To try to love, with equal fervor, all things is to never deeply and generously love anything. To attempt to live another person's expectations is to surrender the one true thing you have to give. Let the young have their limitless paths – there's a grace in that too. Yet the hope is not to roam eternally, but to find the place of belonging. And then belong.

Lent is a grace because it strikes at the idol of endless possibility. When, on Ash Wednesday, we are marked with burnt soot, we hear the words from dust you came and to dust you will return. Dust doesn't have numerous options; its trek is pretty much complete. Of course, dust isn't the end. There's Resurrection and new creation and all the truths that kindle our faith. But first: dust.

There are many (in the church as much as anywhere else) pushing endless visions of all we might accomplish, but Lent asks us to take an honest look at all that. Lent asks us (could we please, just for this stretch of 40 days) to be more discriminating, more present. Sometimes to seek your one truth thing, you have to hide from hundreds of others.

February 20, 2012

A Good Idea

Another house warming gift arrives today, from my friend John Blase. John is a poet and storyteller. Basically, he makes words dance. John is one of those men who, through his writing and his way, helps keep me sane (or at least slightly less off-kilter). You'll want to read John over at The Beautiful Due, and you'll want to snag his latest book, All is Grace, co-written with Brennan Manning.

In A Good Idea, John continues the tale of the rich young ruler and how, he believes, he did eventually come 'round via the fidelity of his poor young wife.

Sell all you have and give to the poor.

His rich young ears took Jesus literally,

causing a domino of shock and recoil

until finally the grievous turning away.

It was so sad. So young and so close.

Jesus thought to pursue the lost sheep

but knew if literal was the cause

literal could never be the salvation.

So with reined-compassion he chose

another way, a chance happening to

pass by the olive grove where the

poor young wife paused daily to feed

the sparrows. He stood at the edge

of her aloneness as she pitched crumbs

to the beggars. His voice still until she

had given all she had to them and only

then he dared speak: Life is a good idea.

She smiled, sensing unfamiliar patience

in him that roused the same in her.

It was merely a scrap but yes -

my husband might ease from striving

and seek my face once more, and

consider the birds fed without trouble.

February 17, 2012

A Human Word

I sat in a coffee shop last week, within listening distance of a chiseled man in a grey suit and perfect hair. He was interviewing another man for a job. This second fellow obviously brought his A game to the poker table: I'll see your $800 suit and immaculate hair and raise you one power tie. After a firm shake and a "hello," chisel man's first words were to tell power-tie man how he'd been at the gym at 4:45 that morning. I'll admit it, he said, I'm intense. He couched it as confession, but I've never seen a man so eager to step into the booth. They talked numbers and mergers and acquisitions. After another firm (and slightly awkward) handshake, they parted ways. With all that exchange, I'm not sure if they shared a single truly human word.

It's easy for me to be smug. I've never owned an $800 suit, and hell will freeze over before you find me in the gym at 4:45. My mercury refuses to acknowledge – much less rise to – that intensity level. Yet I've had many a conversation where I neither asked for nor offered anything truly real or truly human. I can breeze in and out of a space with the best of them. But what do I miss with that shortsightedness? I hope I see chisel man again. I'd like to ask him what he finds so fascinating with pre-dawn sweat and how he keeps that beautiful jet-black mane in impeccable shape.

February 16, 2012

Here Now

Since I've moved into my new digital home, I've asked a few friends to come by and offer me a house warming gift. Over the next week or two, we'll have a few posts that come as gifts to me, and I'll share them with you. The first arrives from my best friend in this world, though she's so much more. Miska is my wife and soulmate, the one person I'd want with me if ever I were shipwrecked – and the one person who has most helped my soul not be shipwrecked.

{Here Now}

{Here Now}

In that liminal space between day and evening

When the mysteries flame forth,

catch fire with the blaze of the dying sun,

then burn down into a smoldering blue light,

I was walking the circuitous, ancient path of the prayer labyrinth,

Soul-deep in silence and offering my heart's prayer to God

with the fervor of one who is seeking yet has already been found,

when I heard the voices; sadly, not of angels

but of humans.

I looked up at the noise and saw them

coming along the bamboo-lined path.

The little boy broke away from his mother and

Ran out onto the stones of the labyrinth with me.

Irritation surged up,

My agenda altered and

My centering meditation fractured.

But remembering the enticing words I'd heard earlier—

The call to walk through my moments and days with

Uncharacteristic leisure, relaxed, unhurried,

present—I was chastened. . .

And reminded of my life back home with two young boys

Who disrupt my quiet, prayerful spaces

With uncanny regularity.

"Aha, a metaphor of my life," I smiled to myself

as I watched the child trying to navigate

his way to the center of this unicursal path,

and I, reluctantly, let go of my original purpose

for being in this space.

I have been asked to love whatever comes,

To take it all "with great trust" in the words of Rilke.

My soul's labyrinth toward divine union,

The perpetual enchantment, the persistent invitation,

Is to see and touch and taste God in the ordinary

Everydayness of all things and in all places,

And to lay down my solitary visions and my ecstasies,

To find the Sacred

Here, now.

February 13, 2012

Beautiful Mundane

I woke this morning, as I do many mornings, to my alarm cranking out "Desperado." It seems appropriate (for numerous reasons) to be asked at the moment of waking whether I intend to come to my senses. It was too early for my taste; it's almost always too early for my taste. It's a second Monday, so I dressed and joined a few friends downtown at The Haven where we dished out a hot breakfast of coffee, cream of wheat, cinnamon apples and fried eggs.

Most mornings, I'm dishing breakfast at home to two boys and a wife. Boiled eggs, oatmeal, grapefruit – we don't vary much. We eat at 7:30. We read a bit of Scripture around the table. After a few frantic rounds of hunting misplaced socks and signing homework and dashing up and down the stairs for sundry forgotten items, we pack the boys off to school. After, I'll usually take a run, with a few prayers offered along the way. Then, like most every adult on the planet, it's to the grind. There may be writing or meetings, study or planning. There's always a list to be tended to, that list scribbled somewhere on this cluttered desk of mine. Fridays offer sweet Sabbath, followed by Saturdays with family chores and grocery shopping and sometimes an attempt at a family adventure. Sunday brings Bodo's bagels at our kitchen table followed by worship around Jesus' Table, with an evening nightcap of egg sandwiches, tea and Downton Abbey. Mondays, we begin again.

This rhythm provides a mundane beauty. It's beauty – a firm beauty that bears up under the years. But it's also mundane. It's rhythmic. It's love that proves itself by the unwavering decision to love well and love steady, over and over. It's a love that lets a boy know that what he needs will always be here, sure and regular as the sun rising. Perhaps he won't notice it for years, but the day will come – I promise you the day will come – when that gracious rhythm will give him a lifeline. It's a love that a wife offers her husband and a husband his wife, a love that says I'm right here, right by your side. We'll steal a kiss every chance we get; but between those toying moments, my love will be present, my love will show up. And keep showing up.

These mundane rhythms, as much as the brilliant flashes, form the person we are. These mundane rhythms are our quotidian liturgy.

This is true in every family, even the Christian family. We're eager to latch on to some new-fangled way of being Christian. Disappointed with our slow progress or restless with the boredom that inevitably sets in whenever you are participating in things that are beautifully mundane, we think there must be some quick way, some non-mundane way. There isn't.

Because I'm a pastor, I'm often asked our strategy for helping people obey and follow Jesus. There's lots of things we will do along the way, as we pay attention to our family and to the particular needs of the particular people in our midst. However, if you want to know our plan, it's about as quotidian as it gets: Gather with your community and worship your God on Sunday. Pray prayers and sing prayers. Receive and give the peace and mercy of Jesus Christ. Hear and believe the Scriptures. Confess your Sins. Receive the Eucharist, drinking deep draughts of grace. Receive a blessing. And then go out into your mundane, beautiful world and love your God and love your neighbors.

If we do those things, over and over, we will find ourselves following Jesus. We will find ourselves receiving and giving love.

image: wildhotrad

February 9, 2012

Mom's Fight

She sat next to me on that gray and blue upholstered couch, the one that pulled out into a bed whenever guests stayed overnight. She sat next to me and stroked my hair, my hair wet with sweat from a fever that revved to 103º and was still pouring on steam. It was a Sunday night, strange those hazy memories: 60 Minutes flickering on the screen, heat, fuzzy, dizzy. I felt like I was trapped in a kaleidoscope.

But my mom sat next to me. I don't remember anything she said. But she sat there, and she fought the fever with me. She fought it for me. She loved me. Because I'm a father now, I know that she was fighting harder than me, that she felt a kind of pain my little, feverish body couldn't yet know.

With the fever still climbing, my mom put me in the bathtub with cold water and ice. I shivered and ached while she poured all her love and energy and fierceness into that fight. And she won. The fever cried uncle.

Today, my mom battles cancer. She's tenacious and strong; but she's got a real brawl on her hands. I wish I could sit with her on the couch and hold her hand and let her rest while I fought for her. I wish I could do more than pray to God, more than text a line of love or plan a visit a few months away. I wish I could say more to my dad than I love you, and you're not alone. I wish I could get my hands around that cancer's neck and squeeze the very life out of it. I wish I could make that bastard cry uncle.

February 6, 2012

Lies and Laughter

The week before last was a bear for Wyatt. Elementary school is like the rest of life: there's sad people and fearful people - and the sad, fearful people take the meanness that's been heaped on them and hurl it onto others. Sometimes my dad-self wants to march onto the school grounds and put the fear of God into a child or two.

After a particularly difficult day for Wyatt, I had words my son needed to hear. I got on the floor with him in his room, and we talked about the truth. We talked about words that are lies and words that are true; and we talked about how truth is something we hold tight, clinging onto for dear life while lies are the things we stare down and then, with a chuckle and a wag of the head, we say, You are just ridiculous. Wyatt liked that. He liked the word ridiculous, particularly when I repeated it, stretching it out (ri------di-----culous) while exaggerating the laughter and the roll of the eyes. These lies (the ones aimed at the soul) aren't something to ponder and dissect; they're something we disarm by refusing them the dignity of a conversation.

This is true for Wyatt in 4th grade. It's true for me at 40 years. By now, the lies are predictable. I've heard most every one (or close cousins) a bujillion times. I can hunker down for the assault and follow that familiar cycle of self-violence. I can give that old snaggle-toothed lie my energy. Or I can stand up straight, breathe deep, and, with the lightheartedness of one who knows nothing's at stake, I can have a laugh and say, You, old pal, are plain ridiculous.

✣

After a couple of these conversations with Wyatt, he asked me, "Dad, when you're a kid, is it bad to love your dad almost as much as God?"

"No," I said, sensing tears, "not at all, Wyatt, not at all."